Pamela D. Toler's Blog, page 31

March 23, 2023

Talking About Women’s History: Three Questions and an Answer with Fiona-Jane Weston/

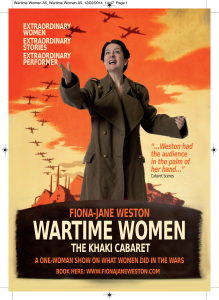

Fiona-Jane Weston is an actor, singer, and writer. Her solo shows have played to packed houses at The Other Palace, The Pheasantry, Crazy Coqs (Brasserie Zèdel), as well as on national and overseas tours.

Fiona-Jane has received rave reviews for her unique take on historical themes and key events in history, most notably women’s history. Her highly acclaimed shows include Wartime Women, looking at the roles women have historically played in warfare and Looking For Lansbury, celebrating the life, heritage and extraordinary career of Dame Angela Lansbury, and musical chat show Fiona-Jane and West End Friends.

She is soon to launch a cabaret and theatre consultancy service that helps with all aspects of creating and managing a small-scale show. Fiona-Jane also writes about theatre and cabaret on her blog Capital Cabarets and Shows Scene, in addition to and for prestigious theatre blogs such as Musical Theatre Review. She has been featured in The Times, The Guardian and London Live TV, amongst other media outlets.

Take it away, Fiona-Jane!

What inspired you to combine your work as a cabaret artist with your interest in women’s history?

Even as a young girl I loved history, and part of my childhood was spent in Queensland, Australia – the state where Germaine Greer grew up and launched her books on feminism. I was studying at an all-girls school and her philosophies inspired me in my formative years. I became particularly fascinated by the concept of Herstory.

Again, even as a young girl, I knew I was going to become a performer, despite my parents’ opposition. In order to keep the peace, I did go down the academic route at university and studied Modern Asian Studies, specialising in Chinese language, politics and sociology.

This led me to examine the changing (and not so changing) role of women in both traditional and modern China, and my thesis study was on the propagandist role of theatre and performing arts in the country.

After graduation, an unusual opportunity came up for me to stay in a dormitory with Chinese student teachers in a compound of Guangzhou province for a year, where I was able to improve my language skills and observe how the society really worked at first hand. I also attended as many live performances of Cantonese and Peking Opera as I could, drinking in the stylised artform and immense skill of the performers.

All this is a long form of pointing out how the two interests were always there, often working side by side.

Fast forward many years now, and I did eventually pursue my career choice to become an actress and singer, and came back home to my native UK, where I had spent my early childhood and also a year when I was 16 years old, because my father was on sabbatical leave from the university where he lectured.

I continued my artistic training here whilst landing acting work at the same time, and in due course met my actor/director husband, who very much encouraged me to keep going.

The life of a performer has always been precarious, unless you happen to be very well connected, which I certainly wasn’t. Things ticking along while I was still looking very youthful, but there came a point when I felt I could not get away with playing the pretty ingenue any longer, and neither did I want to. I was ready for a fresh challenge.

I went into school teaching for a while, but quickly realised I was not going to be happy doing that, and embarked on getting my teaching qualifications for both ballet and the London Academy of Dramatic Examinations (LAMDA) board.

Working towards the LAMDA exams entailed a 1:1spoken examination on a century of drama, literature and poetry, which was fascinating to study, though a tough exam. We could choose the century we wanted to focus on, and I, like an idiot, chose the 20th century. My teacher warned me- “This is the century when everyone could read and write. There’s a lot more work!”

I’m not sorry I did it, though. The 2nd part of that exam was to present a 20 minute presentation of at least one piece of drama, literature and poetry each and link them together through some sort of theme. I chose to look at the changing role of 20th Century Woman through those genres – and that became the theme of my first professional cabaret!

I had always loved watching snippets of cabaret in old films and knew there must be a way to bring these disparate ideas together in a satisfying piece. I engaged a director, who also loved history and literature, and together we researched women, occupations and concerns of women throughout the 20th century, and created a show with songs, drama pieces and poems reflecting all that I wanted to say on the subject. The show was called 20th Century Woman: the Compact Cabaret.

It got good press and led me to New York and an international cabaret conference at Yale University.

My career never looked back. I have been self-producing work on women’s history ever since!

What led you to add videos about historical women to your repertoire?

I had an idea knocking around in the back of my head that I could create a documentary series on women’s history using my performance skills to advance the narrative, much as I do in my shows. I was inspired by the work of British actor Kenneth Griffith, who created documentaries on the Boer War in South Africa, where he would be talking to camera and then ‘become’ the historic character he was talking about.

That’s exactly the approach I was already using in my cabarets. I talk to the audience and then go into character speaking their real words when possible, and use the lyrics of a song to express what they are feeling or what is happening to them. I knew this would be a unique way to present documentaries on television.

What really pushed me into it though, was the pandemic. All venues closed down and no live work was possible. A friend in America, Cece Otto, who does shows on the American woman’s experience, and I got together online and did some live shows over Zoom to both our audiences. I started to really see then how working online could widen my audience and protect me from the vagaries of concentrating solely on live performance.

My biggest challenges were to get used to singing into a phone or computer screen (and that still feels weird) and overcoming the tech (still learning that one, too!), but I recently made one little film on a long-forgotten woman composer Avril Coleridge-Taylor, whose music completely fell out of favour and became nearly impossible to find. I felt it was time to give her back a bit more time in the sun!

The series is titled Women Making History – Then and Now, which gives me the opportunity to look at current women who are pioneering right now. My next set of videos will be on English Queens, and possibly include Camilla, the Queen Consort and the Princess of Wales- both of whom are definitely making history!

What do you find most challenging or most exciting about researching historical women?

The most challenging- and exciting- thing is finding the material itself. Women’s stories have barely been chronicled in the same way men’s stories have. Unless a woman was particularly prominent, no-one really thought to record what she did. This is especially true of the ‘woman next door’ who’s work and roles have changed so much over the last 100 years, and who never thought herself that she was doing anything extraordinary in very difficult circumstances.

My grandmother was a case in point. She lived through two World Wars, was feisty as could be and battled her way through bombings, poverty and five children, including a particularly wayward son. It never occurred to her that she did anything special, nor her eldest daughter, my aunt, who served in the Women’s Auxiliary Airforce (WAAF) during World War II. They were just getting on with it, as far as they were concerned. Why would anyone want to write about it? They were somewhat bewildered when I researched them for my show Wartime Women: the Khaki Cabaret. Sadly, they had both passed away when I got to portray them on stage- mind you, I don’t know how my Grandma might have reacted!

A question from Fiona-Jane: We are both passionate about celebrating women, our accomplishments and role in society. Do you ever feel women in Western civilisations are in danger of losing the ground we have gained? That we could be sleep walking into a new oppressive reality and could literally lose the rights we and our ancestral sisters have fought so hard for? If you do, what do you think we can/should do about it?

After spending much of the last few years watching the rise of Nazi Germany through daily newspaper reports in the United States, I think it is all too easy for people to lose rights because they aren’t paying attention. At the risk of repeating myself: Don’t take what we have for granted. Don’t look away when someone else’s rights are at risk. Don’t expect someone else to do the work.

***

Want to know about Fiona-Jane and her work?

Check out her website: http://www.fionajaneweston.com/

Subscribe to her newsletter: fionajane@fionajaneweston.com

Subscribe to her YouTube channel: https://www.youtube.com/@FionaJaneWeston

Check out her latest program: Avril Coleridge-Taylor – A Lost Musical Legacy:

***

Com back tomorrow for another guest post from a long-time friend of the blog, Jack French. He always brings us good stories.

March 22, 2023

Talking About Women’s History: Two Questions and an Answer with Carol Berkin

Carol Berkin is Presidential Professor of History, Emerita, of Baruch College & The Graduate Center, CUNY. She received her B.A. from Barnard College and her PhD from Columbia University where her dissertation received the Bancroft Award in 1972. She has written extensively on women’s history and on the American Revolution, the creation of the Constitution, and the politics of the early Republic. Her books include Jonathan Sewall: Odyssey of an American Loyalist [Columbia University Press] which was nominated for the Pulitzer Prize; co-editor of Women of America: A History [Houghton Mifflin & Company], the first published collection of original essays in American women’s history; First Generations: Women in Colonial America [Hill & Wang]; A Brilliant Solution: Inventing the American Constitution [Harcourt], awarded the Colonial Dames of America Book Prize; Revolutionary Mothers: Women in the Struggle for American Independence [Knopf]; Wondrous Beauty: The Life and Experiences of Elizabeth Patterson Bonaparte [Knopf] ; The Bill of Rights: The Struggle to Secure America’s Liberties [Simon and Schuster]; and most recently, A Sovereign People: The Crises of the 1790s and the Birth of American Nationalism. She has appeared in over a dozen documentaries on colonial, revolutionary, and civil war history, given lectures on her specialties at major universities in the United States and England, and participated in faculty development across the country under the U.S. Department of Education’s Teaching American History Grant Program. She has directed summer institutes for The Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History, Mount Vernon, and the NEH. She has served on the board of the National Council for History Education, the Staten Island Historical Society, and the Society of American Historians and on the Scholars Board of the New-York Historical Society’s Center for the Study of American women. She is a frequent participant in the New-York Historical Society’s lecture series, and is also the editor of the Gilder Lehrman online journal, History Now. Her favorite pastime is doting on her three grandchildren, Talulla, Noa, and Asher.

All I can say is, wow! Take it away, Carol!

You’ve written about a lot of interesting women. Do you have a favorite?

I am especially glad I had the chance to write about Elizabeth Patterson Bonaparte whose story I told in my book Wondrous Beauty: The Life and Adventures of Elizabeth Patterson Bonaparte. Elizabeth – or Betsy as she was called– was born in the late 18th century, the daughter of a wealthy Baltimore merchant, and she was by all accounts one of the most beautiful and brilliant women of her generation. She was restless and unhappy as a young woman, for she believed she belonged on a larger, less constricting and more sophisticated stage than the young republic had to offer a woman. She considered her native country a cultural backwater, its men consumed by money-making and its women content to live narrow lives as wives and mothers. She longed for the excitement and intellectual stimulation of European culture. Her discontent drove a wedge between her and her father whose rags to riches story left him obsessed with respectability and deeply socially conservative. At 17 Elizabeth’s wildest dreams came true: she met the youngest brother of Napoleon Bonaparte, an 18 year old naval officer who was visiting America. Jerome Bonaparte was, in fact, spoiled, selfish, and a womanizer but all she saw was his French manners and his charm—and her way to escape the mundane life of a genteel American woman. They married against her father’s wishes and, as they soon learned, against Napoleon’s as well. The emperor offered his brother an ultimatum: renounce this marriage, marry a member of the European nobility, and I will make you a king of one of the German territories I control , or, remain married to this commoner and I will disown you. Jerome Bonaparte chose option one, abandoning his young wife and her infant son without hesitation.

But this was far from the end of Betsy’s story. She pulled herself together, refused to ever depend on a man again, dared to take herself alone to Paris and London and later to Italy and Switzerland—breaking all the rules for well -behaved elite American women! Men fell in love with her by the dozens but she never considered marrying any of them. Instead, after becoming the belle of French literary salons—admired not only for her beauty and wit but her intelligence, she discovered to her delight that she did not need to bask in the light of a man; she could achieve her goals independently. Unfortunately, she focused most of her emotional energies on a long campaign to force the Bonaparte family to acknowledge her son and only child as a legitimate heir to the French imperial throne. For decades she pursued this dream, despite her son’s lukewarm response to her vision of a life among the royalty of Europe. In the end she failed, rejected by the Bonaparte heirs and, in her eyes, betrayed by her son who married an American heiress and settled contentedly into the bourgeois world of the US that she so despised.

Betsy’s only other consuming passion was financial independence and she proved to be a shrewd business woman and investor. She became the first self-made female millionaire of the 19th century, ironically engaging in exactly the money-grubbing she condemned in her father and American businessmen in general. In older age she returned to Baltimore, where she made clear her continued rejection of female domesticity; she refused to set up housekeeping in any of the properties she owned. She lived until her 90s in a rented room., surrounded by memorabilia and ball gowns from her days as the belle of Paris and Florence. She grew increasingly bitter and eccentric and could be seen, carrying her parasol and a large handbag as she went door-to-door collecting the rents from tenants in her many properties. Yet she retained her beauty and her wit. When she was 94 a local newspaper reporter visited her and wrote that she remained a “wondrous beauty.” She died soon afterward, refusing to be buried in the Patterson family cemetery. As she wrote: “I have lived alone and I will die alone.”

Many readers of my biography disliked Elizabeth Patterson Bonaparte. They consider her selfish and cold, and they see her life as a tragedy marked by her obsession with elevating her son to the throne. But I admired her. Imagine what it took to carve an independent path as a genteel woman in late 18th and pre-civil war America! She fulfilled her dreams, all on her own. She unleashed her intellectual talents, outdid her father and brother’s financial skills, traveled widely on her own when this was considered scandalous in America, and did not succumb to the many appeals by men to marry and be “taken care of.” She was witty, brilliant, and valued her mind over her looks. Her faults were many, but her strength of character allowed her to defy her moment in time and place and live as an individual rather than be defined by the female roles of her day. I say, Brava for her!

What do you find most challenging or most exciting about researching historical women?

There is such satisfaction to be able to look into the mirror of the past and see a female face. [< Revolutionary Mothers, joined earlier pioneer works in showing that the Revolution could not be adequately or accurately understood until women’s many roles in its unfolding were written into the narrative of the struggle for independence.

A question from Carol: In Alice Through the Looking Glass, the White Knight and Alice are living chess pieces on a chess board. Alice cannot understand why it is so hard to move across that board and win the game. The Knight explains to her that, sadly, in this world, you have to run twice as fast just to stay in the same place. What do you think can be done —or is being done —today to ensure that the fight for women’s equality will not be stuck running hard to stay in the same place?

That is the bazillion dollar question, isn’t it?

Ultimately, I think the answer is the same for women’s equality as it is for democracy in general: Don’t take what we have for granted. Don’t expect someone else to do the work.

Easy to type. Hard to do.

***

Come back tomorrow for three questions and an answer with cabaret performer Fiona-Jane Weston

March 21, 2023

Talking About Women’s History: Three Questions and an Answer with Deborah Wastell

Deborah Wastell is an actor, writer, and theatre maker. She is the co-founder and artistic director of “The Female Edit” and in 2022 she created the podcast “Dinner Party Dames” where each episode she talks to a different guest and together they co-host a dinner party where all the guests are interesting women who her co-host would like to invite to their ideal dinner party. She lives in London with her husband and their Miniature Schnauzer, Ripley, named after Lieutenant First Class Ellen Ripley… a strong contender for Deborah’s own Dinner Party guest list.

Take it away, Deborah!

Photo credit: Ruth Crafer 2022

Dinner Party Dames has an unusual format: an imaginary dinner party to which your real life guest issues invitations to women who have had an impact on them–historical current, and occasionally fictional—in response to prompts from you. What inspired you to create this format?

In 2018, for the centenary of women’s suffrage in the UK, I decided to nominate a different woman every day on my social media accounts, and I very quickly realised that the majority of the women who instantly sprang to mind were from specific fields and geographical regions, so I spent a lot of time researching women who had achieved remarkable things from as many walks of life, and in as many different fields, as I could think of. I asked for, and received, loads of suggestions from people who were following the project, and I found out about some astonishing women – the knowledge I gained was not always a lot, but the stories of these women and achievements drew my attention to experiences and questions I’d never really thought about – not because of a lack of interest, but a lack of awareness.

A huge amount of work went into that project, so much so, that once 2018 came to an end, I felt like I wanted to do more with it – or to develop it in some way, but as with so many things, the various ideas of where to go with it were relegated to a notebook alongside many other creative seeds that had been planted over the years – including random notes I’d made after seeing Judy Chicago’s “Dinner Party” in Brooklyn the following January (2019), which I also wanted to use as an inspiration to develop something from.

Both ideas lingered side by side but unrelated, and then about two years later, while I was “Marie-Kondoing” some old notebooks it just suddenly came to me.

It’s one of those questions that pops up, isn’t it? “Who would invite to your ideal dinner party?” And I always love to hear people’s responses – which are very often very male heavy, because most of the history we are taught – whether it be at school, or through literature, cinema, or television is very focussed on men. So what if I asked different people “the dinner party question” but the guests had to be women? I love podcasts, and one of the things I enjoy about them, is the feeling they give you of just having an informal chat with interesting friends, so I liked the idea of creating something that welcomed in, not only the guest, but also these brilliant women, and – hopefully(!) – the listeners too.

I thought the different prompts were a way of making the process of choosing guests a bit less daunting and also a bit more varied for my guests – I figured splitting it up into specific categories was easier than just leaving it totally open ended.

How would you describe the purpose of the podcast?

At its heart, I think the purpose of the podcast is to celebrate women. And to pique people’s interest in women they may never have heard of. The format means that the focus isn’t specifically on history – it can be – it’s very much dependent on the guest, but sometimes it ends up being very contemporary. What I really want is for people to listen to an episode and come away wanting to find out more about the women we’ve talked about, whether that means reading up about historical achievements, listening to music by the women discussed, or watching a movie they directed. And then for them to tell other people about how brilliant these women were.

Do you think Women’s History Month is important and why?

So important. I hope that one day it won’t be. But for now, so many women’s stories are just not told. Whether those stories be individual or collective experiences most of the stories we are told are those of men. Predominantly straight men, and white men. So many of my my guests start off our chats commenting on how “loads of men sprang to mind” but they had to think harder to find a woman to fit the category – and make no mistake, this is not because women have achieved any less than men – in many cases it’s the historical equivalent of the meeting room scenario where a woman will pitch an idea multiple times, only to be ignored or dismissed and ten minutes later a man pitches the same idea to rapturous applause…

Until the day comes when our school history books have as many chapters dedicated to women as there are to men, and our biopics are as likely to have women in the title roles as men, we will need Women’s History Month.

Image credit: Rebecca Windsor 2021(photo) Charlotte Ive 2022 (artwork)

A question from Deborah: When I talk to people on “Dinner Party Dames”, I ask them to choose between six and eight guests. The categories the guest fall into are these:

1) The first woman you remember being inspired by;

2) The woman whose work or ethos has led you to living your life in a certain way (be the influence tiny or huge);

3) A woman who works in your field;

4) A woman who works in a completely different field to your own;

5) A woman you know in real life;

6) A woman who may be considered controversial;

7) An imaginary friend – a character from any form of fiction;

8) A wildcard

At the end of each dinner party I (very cruelly!) tell my guest that only one of the women they have invited can stay behind for an after dinner drink… they can choose any guest other than their real life connection – who would you choose to stay behind at the end of YOUR dinner party, and which category would they have fallen into in the seating plan, and why?

I have to admit, when I listen to your podcast I always think about who I would choose. And now I get to choose! Because obviously I can’t answer the question about which guest I would invite to stay behind without making up my entire list. So if you’ll excuse me for a moment…. Okay, I’m back. I’d invite Harriet Vane, the female foil to Peter Whimsey in Dorothy Sayers’ mystery novels. I’ll put her in the imaginary friend category, though in truth I could just as easily have put her in the influence slot. Certainly her picture of educated women’s lives helped shape my image of the life I wanted.

I’ve read the novels many times over the years. The thing I like about her as a character is that she is unrelentingly herself, even when it isn’t comfortable. You could do worse than sharing a glass of whiskey with a prickly, smart woman at the end of the day.

***

Want to know more about Deborah and Dinner Party Dames?

Check out the podcast: https://dinnerpartydames.buzzsprout.com

Follow her on Twitter: https://twitter.com/dinnerpartydame

Follow her on instagram: https://www.instagram.com/dinnerpartydames/

Follow her on Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/dinnerpartydames

***

Come back tomorrow for two questions and an answer with historian Carol Berkin

March 20, 2023

Talking About Women’s History: Three Questions and an Answer With Rebecca Grawl

Today I am pleased talk about women’s history with Rebecca Grawl, founding member and Vice-President of Education for A Tour of Her Own, a tourism company in Washington, D.C. That specializes in women’s history tours, book talks and virtual experiences.

Rebecca is a professional tour guide, historian, and author who holds a Bachelor of Arts degree in American Culture from Randolph-Macon Woman’s College (now Randolph College.) She has over a decade’s experience in tourism, public history, and museum education. She works with a wide array of companies, organizations, and audiences to bring our nation’s history to life in engaging and innovative ways.

Rebecca can be seen on Mysteries at the Museum on the Travel Channel and heard as a lead contributor for the Tour Guide Tell All podcast. She is a past board member of the National Woman’s Party and a consultant for Above Glass Ceilings, a firm dedicated to advancing women in the workplace. Her book, authored with A Tour of Her Own president Kaiatlin Calogera, 111 Places in Women’s History in Washington, DC That You Must Not Miss, is a travel guidebook that encourages readers to explore sites and stories about women, many who are overlooked in traditional textbooks.

Take it away, Rebecca:

Is it hard to find women-centric places to include on your tours?

I actually love this question because on the surface, the answer is yes but in reality, it’s much more complex than that. One of the driving motivations for the founding of A Tour of Her Own is the lack of representation for women and women’s history in public spaces in D.C. We are underrepresented on the National Mall, in the Capitol Statuary collection, and on the names of buildings. And yet, the more you dig in and peel back the layers, the more we can find women’s history right under our noses. When we started working on our book 111 Places in Women’s History That You Must Not Miss, we were worried about finding 111 unique places in DC but by the end of the process, we had discovered that there are many places where those stories can be found – you just often have to look beyond the traditional ways in which we think history should be shared.

How do your virtual tours work? Are they also D.C. based?

Our virtual programs are presented via Zoom and ticket holders can either join live or access a recording after the event. Our guides present the tours in a lecture-style with a visual presentation, with participants asking questions or giving feedback via the chat box or a live Q&A at the end. While still focusing primarily on D.C. based stories and locations, this medium allows us flexibility that’s not always possible on the ground. As a guide, I personally love being able to integrate more media in my tours – virtually, I can share images, videos, and audio that bring the story to life in a new way. Place-based learning is so important and our goal is to bring people to the places where history happened but in a virtual tour, we’re not bound by what is open, accessible, easy to walk or drive to, or a price of admission. Creating virtual programs really allowed us to connect with a much broader audience and expand the way we tell these stories. We have developed some really exciting programs like our Mrs. America meetup, which used the popular FX on Hulu series to share women’s history of the 1970s. Currently, we are hosting a virtual book club once a month and sharing behind-the-scenes reflections of our book. Each meeting focuses on 11 chapters and we plan to cover the entirety of the book by the end of the year!

How do you define women’s history?

For me, women’s history is about taking a holistic and intersectional approach to understanding women’s role in our political, cultural, and social history. Just as we try to move beyond the Great Man theory of history, I think it’s important to look at women’s history as not just identifying a handful of key women that need to be part of a canon but rather exploring the varied and complex ways in which women have interacted and influenced the events of their day. Women’s history is not monolithic and it’s not a universal experience – it is complicated, vast, and diverse and I think we are still in the process of reconciling that. Additionally, we often say that women’s history is American history (and American history is women’s history) and while Women’s History Month is a vital and essential component is raising visibility and starting conversations on women’s history, the goal has to be taking a more balanced and nuanced view to how we discuss and interact with history every single day.

A Question from Rebecca: What’s your experience been like as a historian and writer who focuses on women’s stories?

I took an indirect path to writing women’s stories.

It’s where I started. As a kid, I read every biography I could get my hands on about historical women who ignored social boundaries and accomplished things—the kind that are written with the intention of inspiring young girls. I was indeed inspired. My grade school’s revolving library owned a whole series of them. Every week a new one arrived and I snatched it before anyone else could get it, eager to read about Clara Barton, Madame Curie, or Julia Ward Howe.

I never lost my interest in women’s stories, but my life as a history buff took an unexpected turn when at the age of eight or nine I fell in love with Rudyard Kipling’s Kim. (Kipling’s India put me on the path to a PhD in South Asia history.

It wasn’t a straight path. And it wasn’t a short one. The first day of my PhD program at University of Chicago, my advisor said, “You know there are no jobs, right?” I knew, but I didn’t care. Without the promise (or perhaps the threat) of a teaching job at the end of the road, I kept wandering down fascinating by-ways.

After I got the degree, there were still no jobs, so I started writing for a popular audience and I kept chasing whatever historical story caught my imagination. What I wrote about probably looked pretty random to an outsider, but by and large it clustered around one central theme. I feel strongly that as a society we need to hear the stories that don’t get told in high school history classes: the history of other parts of the world as well as history from the other side of the battlefield, the gender line, or the color bar.

As a result of my historical wanderings, in 2015 I was asked to write a work of historical non-fiction about Civil War nurses as a companion volume to the PBS historical drama, Mercy Street. That book took me back to my history-nerd roots and a topic that had fascinated me for years: the roles women play in warfare and how those roles are rooted in and occasionally help change a society’s fundamental beliefs about women.

And that’s where I’ve stayed.

***

Interested in learning more about A Tour of Her Own?

Check out the website: https://www.atourofherown.com/

Follow them on Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/atourofherown/

Follow them on Twitter: https://twitter.com/atourofherown

***

Come back tomorrow for three questions and an answer with Deborah Wastrel, host of the podcast Dinner Party Dames

March 17, 2023

The Only Woman

The concept behind Immy Humes’ The Only Woman is fascinating: one hundred photographs that include one woman in a group of men, ranging in time from the 1860s through 2020, drawn from hundreds of examples Humes collected over the years. Some are well known—both the woman and the photograph. Others are literally unknown, including a woman identified only as “Mascot.” (Grrr.)

Humes presents the pictures twice. First she shows the photographs as full page images accompanied by a brief essay, in no particular order that I could discern, though given the thoughtfulness of the work as a whole I have no doubt there is an organizing principle. Then she arranges the photographs in chronological order as black and white thumbnail images, with the only woman in each image identified with a white circle. I found this version fascinating. It not only made it possible to go back and find the woman in the larger photos—something I found difficult to do in many of the pictures*—but it gave many of the women a prominence that they otherwise did not enjoy. (Maybe that’s two ways of saying the same thing now that I think about it.)

Humes sums up the impact of the photographs as a whole in the brief, provocative essay that accompanies them: “Against this wild variety of time, place, occupations and cultures is a repetitive counterpoint of sameness. The same ludicrous constellation of many men, one woman, over and over again.”

I’ve been dipping into the book for several months now, considering the stories and images that Humes shares. I’ve read her introductory essay several times. There are women I want to know more about and ideas that I want to think over.** (I’ve also come to the conclusion that if you are going to be the only woman in a photograph of formally dressed people arrayed in rows and facing the camera, you should wear a hat if you want to be seen: the biggest, wildest hat you can manage.)

It’s been an interesting counterpoint to the book I’m writing about a woman who was often the Only Woman in the Room, except when she wasn’t.

*Think a real life version of “Where’s Waldo?”

**Just so you know, some of those ideas and thoughts may well appear in my newsletter, which will resume publication once I turn in this book manuscript. (May 1 or bust!) You can subscribe here http://eepurl.com/dIft-b —May 1 is practically tomorrow.

* * *

Come back on Monday for 3 Questions and an Answer with Rebecca Grawl of A Tour of Her Own.

March 16, 2023

Talking About Women’s History: Three Questions and an Answer with Einav Rabinovitch-Fox

Einav Rabinovitch-Fox is a modern U.S women’s and gender historian who teaches at Case Western Reserve University in Cleveland, OH. Her research examines the connections between fashion, politics, and modernity, particularly the role of visual and material culture in social movements. Her recent book, Dressed for Freedom: The Fashionable Politics of American Feminism explores women’s political uses of clothing and appearance to promote feminist agendas during the long 20th century. Her writing has been published in academic journals and books including the Journal of Women’s History, the International Journal of Fashion Studies, American Journalism: Journal of Media History, as well as popular media such as The Washington Post, The Conversation, Public Seminar, and History News Network.

Take it away, Einav!

We’re all familiar with the challenges of finding sources for writing about women from the distant past. What are the challenges of writing about women from the early to mid-twentieth century?

In a sense, the past is always a foreign country, and although we are less removed from the modern period, and are more familiar with it, I think some of the challenges remain. This is especially true when writing about women, as for so long, these histories were considered frivolous or not important, so I think that even when writing about women from the early to mid-twentieth century, there are still challenges in finding sources about them, or in finding sources that really center women’s voices and experiences. This is especially true with regards to women of color, working-class women, or other marginalized women, for whom there is still scarcity of sources.

Moreover, this sense of familiarity with the recent past can be deceiving. There is always the risk of interpreting things wrong or to draw conclusions based on our own experience and not necessarily on the experience of women in the past. Things have changed so dramatically in the life of women during the first decades of the twentieth century, that even for a woman living in the 1930s, the 1900s didn’t seem so liberating, not to mention for someone living in 2023. I always try to meet the women I write about where they are, to understand their world and how they were able to navigate it, and what challenges they had to overcome that maybe I don’t anymore.

Another thing to consider, especially when writing about more recent periods, is that the women I write about are perhaps still alive or have family members who are still alive. And while this is also true when writing about the distant past, I think that the real-life presence of women who lived in the recent past can bring more challenges to writing about them. I often feel I have more responsibility towards them to get the story right, but also to be more sensitive in how I tell their story. I also take into consideration what would be the repercussions of writing about personal or uncomfortable aspects of their lives. In that sense, it is the sense of familiarity that actually presents a challenge to distance yourself from the subjects of your writing.

Your work focuses on the way visual and material culture shapes and reflects class, race, and gender identities. What do we learn when we use images as more than just illustrations?

In a way, an image is just like any other historical source that can tell us something about the past. Especially when researching women’s history and other marginalized communities, what we often have is visual and material evidence, so it is actually a very important source to understand women’s history. Not many women left for us written records in the form of letters or diaries, but we can learn a lot about their everyday life and what they cherished and enjoyed from their dresses, embroidery, and small possessions.

Photographs, paintings, and illustrations contain a lot of information about the past, and so we need to learn to read them just like we read written sources. Material objects offer us even more information, as one can tell a lot when examining wear-and-tear of clothes, or use of other items. I think once we train ourselves to look at images more than just illustrations, but as historical sources, we can also begin to ask questions about them and discover that they can tell us a lot of things about the past.

What was the most surprising thing you’ve found doing historical research for your work?

Writing about fashion, I got to do research not only in archives but also in costume collections, which are archives made of dresses and other clothing articles and accessories. The most surprising thing about it is how different dresses look and feel like in real life, compared to an image or an illustration. Looking at an actual garment: How it is constructed, from what materials, as well as how much of it worn and torn, can tell you a lot not only about the piece itself, but oftentimes also about the person who wore it, as items that arrive to costume collections are almost never anonymous.

One of the most exciting finds are the times that you can match an actual dress to an image of the person who wore it, or a description of them wearing it and how they felt in this garment. Yet, exciting finds can also happen when you get to feel and touch the garment and understand better issues of comfort and proportions, something that often gets lost in images.

One example of that, which to me was very surprising, was when I got to see a bathing suit from the 1920s in one of the collections I visited, which was in Smith College. Bathing suits in the 1920s were quite revolutionary at the time, because they exposed women’s hips and shoulders and were very revealing of the body. It even caused some municipalities to try and ban them on the beaches as they were considered “inappropriate” and even “immoral.” Bathing suits were really the symbol of a feminist consciousness and liberation in the 1920s, so imagine my surprise when I got to touch it, and discover it was made from wool, maybe the last material I would like to go into the water dress in. Realizing that bathing suits were made of wool not only made me appreciate the invention of Latex, but also got me thinking differently about what comfort meant to the women who wore these suits and what made them so revolutionary, and how we today judge comfort.

Question from Einav: You write historical works for popular audiences, how do you make your audience care about women’s history? How do you show them that women’s history matters, that it is important?

When I was writing my dissertation, I had a day job that required me to work with a great many tradesmen, many of whom had doubts about taking instructions from me. (Probably all of them had doubts at the beginning. Some of them were simply more polite about it than others.) I changed their minds one guy and one project at a time.

In many ways, making readers care about women’s history is very similar. Other than this annual series of mini-interviews, I don’t try to make my audience care about women’s history in the abstract. Instead, I do my best to make them care about a particular woman or group of women or a specific story. Part of doing that is to make it clear why that story and that woman matter and how putting them back into the historical record makes our understanding of the past richer.

***

Interested in learning more about Einav Rabinovitch-Fox and her work?

Visit her website: www.einavrabinovitchfox.com

Follow her on twitter: @DrEinavRFox

***

Tomorrow it will be business as usual here on the Margins with a women’s-history- related blog post from me. (Subject to be determined.) But we’ve still got more people talking about women’s history from a lot of different angles next week. Don’t touch that dial!

March 15, 2023

Talking About Women’s History: Two Questions and an Answer from Eleanor Fitzsimons

Eleanor Fitzsimons is an Irish researcher and writer who specialises in historical and current feminist issues. She has an MA (first class honours) in Women, Gender and Society from University College Dublin. Fitzsimons is the author of Wilde’s Women: How Oscar Wilde Was Shaped by the Women He Knew (Duckworth, 2015). She is an honorary patron of the Oscar Wilde Society, and a member of the editorial board for society journal The Wildean. She has worked as a television researcher for the Irish national broadcaster RTÉ, and was a contributor to The Importance of Being Oscar (BBC2, April 2019). Her second biography The Life and Loves of E. Nesbit (Duckworth, 2019) was a Sunday Times Book of the Year 2019, and was included in the Washington Post Top 50 Non-Fiction Books of 2019 and the Dallas Morning News Top 100 Books of 2019. Her work has been published in several academic journals and books.

Take it away, Eleanor!

What do you find most challenging or most exciting about researching historical women?

In a sense, the aspect I find most challenging about researching historical women is also what makes this research most exciting and rewarding. I’m sure we’re all acutely conscious of the fact that women’s lives have often been very poorly documented. Where their experiences have been chronicled, this was often done through a gendered lens, their achievements undervalued or, if deemed worthy of commenting on, attributed to men. When researching my most recent biography, The Life and Loves of E. Nesbit, I discovered that many reviewers assumed Edith Nesbit was a man. One critic in The Graphic described her as “a man of rare poetic gifts and of true honest purpose”. Nesbit was fully aware of this confusion and occasionally found it funny. “All the reviewers took me for a man,” she told a friend, “and I was Mr Nesbit in the mouth of all men until I was foolish enough to dedicate a book to my husband, and that gave the secret away”. Literary women have often found it beneficial to disguise their identity, or even to write as men. Similarly, women who operated in traditionally masculine spheres, such as politics, science or medicine, were often castigated for not behaving as they should. In each case, you are required to challenge and evaluate what are often very biased accounts of their lives.

When we recover women’s lives, the challenge often lies in finding any information about them at all. The advantage of having to work harder is that those of us who write about women are obliged to seek out neglected primary sources – letters, diaries, census records, death certificates, court records such as bankruptcy proceedings, and accounts left by reliable family members and friends. I find this so rewarding and exciting. In a sense, I regard myself as a literary detective, a Miss Marple of the archives. When I wrote about Harriet Westbrook Shelley, first wife of Romantic poet Percy Shelley, who was completely overshadowed by his second wife, Mary, one of my better sources was a series of letters she exchanged with a remarkable Irishwoman named Catherine Nugent. Although she never married, Catherine felt obliged to pose as a widow and call herself “Mrs Nugent”. A male friend described her thus: “a wonderful woman—altho’ very plain, little and republican looking . . . Catherine Nugent has amazing spring and elasticity of mind, as if her mind made her forget that she had a weak body”. Both women are largely forgotten. Fortunately, their letters, with notes about Catherine’s life, were published by her friend Alfred Webb, a printer in Dublin, as Harriet Shelley’s Letters to Catherine Nugent. Such treasures are often buried in the archives but digitization of old books has ensured that they are increasingly accessible to us all.

What work of women’s history have you read lately that you loved? (Or for that matter, what work of women’s history have you loved in any format?)

There are so many worthy candidates! I’m going to choose a brilliant but unconventional book, A Ghost in the Throat by Irish poet and essayist Doireann Ní Ghríofa. Using beautiful, lyrical language, Ní Ghríofa intertwines her own experiences as a young mother in modern-day Ireland, with the story of Eibhlín Dubh Ní Chonaill, an Eighteenth-Century Irish noblewoman. On discovering her husband has been murdered, Eibhlín drinks handfuls of his blood and composes an extraordinary poem, Caoineadh Airt Uí Laoghaire, in his honour. Enchanted by this powerful poem, Ní Ghríofa becomes obsessed with uncovering the truth about the interior and exterior life of the shadowy woman who wrote it. The biographical details she uncovers are compelling enough, but what really sets this exceptional book apart is Ní Ghríofa’s extraordinary insights into the way we are shaped by our experiences, her enchanting exploration of language and ideas, and her celebration of the power of words to console and transport us. I cannot recommend it enough!

A question from Eleanor: I think Women’s History Month is fantastic! What do you think the key achievement of the celebration of Women’s History Month has been? Does it allow us to reach and retain an audience that would never normally take an interest in the lives and experiences of women?

As so many of us do, I have mixed feelings about Women’s History Month.

On the one hand, I wish that we didn’t need it: that’s women’s roles in history were simply an integrated part of how we think about history and the way history is taught. But that simply isn’t true: according to a statistic shared by the Remedial Herstory Project, in 2022 teachers spent between five and twenty percent of their history curriculum time on women’s history, with five percent being the plurality. (What do you want to bet that most of that five percent occurred during Women’s History Month?) That means that the mandate to teach and talk about women’s history in March remains important.

At the same time, I LOVE the festival feeling that surrounds Women’s History Month. Every year, I make new connections with other people who share my passion for this subject—here at History on the Margins and elsewhere. With each new connection, we amplify each other’s reach.

***

Want to know more about Eleanor Fitzsimons and her work?

Check out her website: https://eafitzsimons.wordpress.com/

Follow her on Twitter: https://twitter.com/EleanorFitz

***

Come back tomorrow for three questions and an answer with historian Einav Rabinovitch-Fox

March 14, 2023

Talking About Women’s History: Three Questions and an Answer with the Hosts of Women Who Went Before

Rebekah Haigh and Emily Chesley host and produce Women Who Went Before, a gynocentric podcast on the ancient world. Both are PhD candidates at Princeton University. Rebekah specializes in Religions of Mediterranean Antiquity and is writing a dissertation that explores gendered piety and violence in the Dead Sea Scrolls and ancient Judaism. Emily researches late antique history, and her dissertation examines women in the eastern Roman Empire amidst the military and religious upheavals of the 5th–8th centuries CE.

Take it away, ladies!

Photocredit: Sameer Khan/Fotobuddy, LLC.

What inspired you to start the podcast?

Rebekah: We certainly didn’t set out to start a podcast! It all began as a Covid project. In spring 2020 Emily and I had a conversation about why neither of us had spent much time thinking about women and gender in the ancient world. We realized it was a huge gap in our preparedness to be scholars, but there was a pandemic happening and there were no classes or library access. Then we thought “since, we’re stuck at home … let’s try starting a reading group.”

We weren’t reading around specific historical women or texts about them. We were doing a lot of theory work work: looking at different waves of feminism and how they intersected with scholarship. It wet our appetite because when you do that kind of theory work, you’re always trying to find connections like, “Okay, could I apply it to women that I’m familiar with? The historical texts I’m familiar with? I kind of want to try it.”

Emily: As it happened, it ended up being pretty popular. People joined from beyond Princeton, from different universities and even multiple countries. We realized that we weren’t the only ones who felt there was a gap in our education! And that shared enthusiasm fanned the flame.

Even people who weren’t enrolled in graduate programs heard about our group through social media and their friends, and they reached out. Ultimately their interest made us realize that this topic wasn’t just of interest to people in the Academy; there is a hunger across society from people eager to learn about women in the ancient world. And then a conversation Rebekah had got us thinking towards a bigger picture.

Rebekah: At the end of that year, an administrator and mentor suggested turning our reading group into something more substantial, something that would reach that wider audience. As we brainstormed public scholarship formats, we assumed there were already a bunch of historical podcasts about ancient women. But while there were loads of podcasts on history, even ancient history, we couldn’t find anything on ancient women. Medieval women, women in 19th century America, but nothing about women in the ancient world. So we decided to make a podcast.

Emily: It’s been a really rewarding journey so far! Our first season just finished, and we’re in preproduction for season two which will release in the fall.

Rebekah: And one of the first interviews we recorded for the podcast, with Solange Ashby on the warrior queens of Meroe, was someone who had participated in the original reading group!

What work of women’s history have you read lately that you loved? (Or for that matter, what work of women’s history have you loved in any format? )

Rebekah: Well, the answer that jumps to mind is going to reveal a lot about me and how I first came to love history – and also a lot about Emily. Both Emily and I have this shared experience of being home schooled with the same curriculum, one of the things we initially bonded over. We even read the same cluster of historical novels about women. One of which was Mara, Daughter of the Nile, a book that I’ve always credited for my early interest in ancient history. The novel was about this young girl who lived in Egypt. She’s not a real person. But the book gave me a taste of what it might be like to live in the ancient world and I wanted to know more.

Emily: Historical fiction can powerfully engage you, whetting your appetite for “thicker” history books. Rebekah and I definitely shared a love rooted in a childhood of reading about women in history, whether real or fictional.

As far as books today, I have to caveat that as a grad student, I don’t read as much pure history outside of work. I find I have to take a mental break and separate out the other kinds of reading from the work-reading (which yes, I also enjoy; and if you check the source lists for our episodes you’ll find many of my go-to academic texts on women’s history). I love to read for pleasure, but it’s usually fiction of some kind, whether YA or Dorothy Sayers or something in between.

Rebekah: Yes, exactly. I don’t read much nonfiction beyond my own research. In my spare time, I want a break from heavier stuff, so I will usually read fictional stuff or sci-fi but not a lot of biographies of women.

Emily: One book both Rebekah and I read, which isn’t a history of the past so much but in a way is a history of our present, is Living A Feminist Life by Sara Ahmed. She does a wonderful job of linking academic work on feminist theory with lived women’s experiences in a practical way. She applies insights from feminist scholars to help women, especially women of color and queer women, understand their own day-to-day lives and the resistance they receive from the world. One of Ahmed’s famous ideas that recurs throughout her corpus is that when you point out a problem you become the problem, and it’s helped encourage me in moments advocating for gender equality in the workplace.

In terms of more traditional histories about women and still grippingly written, I loved Code Girls by Liza Mundy, and The Radium Girls and The Woman They Could Not Silence by Kate Moore. The latter is particularly moving; it’s about Elizabeth Packard, a 19th-century woman from Illinois whose husband institutionalized her, and it looks at the laws in that century that basically gave husbands complete control over their wives. Julia Cooke’s Come Fly the World is a history of the first jet-set stewardesses for Pan Am. I admit I was first intrigued by the topic (speaking of women’s history in other formats) because in college my roommates and I watched the short-lived TV series Pan Am, crowding onto our old couch every week and obsessed with the glamor of it all. Then reading this archival history, you can’t help but be struck by the indignities and sexism these women endured while breaking the glass ceiling and their fortitude in the first decades of commercial air flight.

This is in some ways an atypical women’s history book because she is still alive today, but Nell Painter’s memoir Old In Art School also stands out. She’s an award-winning historian of African American history and race, and one of her most famous books was The History of White People. Then after she retired, she went to art school and started working as an artist. Her memoir describes that journey, exploring the links and tensions between her academic work and her art practice, and mulling on her experiences as an older black woman in the predominantly white and younger art world.

Rebekah: I can add a nonfiction book which I have managed to get halfway through, The Way of Perfection by Teresa of Ávila. The book is not a biography or a historical piece but rather personal reflections by a Spanish nun and mystic who lived in the 16th century. She was pretty radical for her time. Teresa led a monastic reform that made many people unhappy with her, but her writings have endured the test of time. The Way of Perfection is a book about prayer and meditation, how to be intentional about your spiritual life. Though written hundreds of years ago, it remains an insightful piece on practices of meditation, a topic that I’ve been interested in for a long time.

I think one of the reasons that her personal reflections, and works like it, still speak to everyday people is because in them we have access to women’s inner thoughts and feelings, something we don’t usually have with the ancient world. There is a degree to which when we have access to what women are writing and what they’re thinking, it’s easier for contemporary history aficionados to identify with those figures and to find space for themselves and their stories.

What was the most surprising thing you’ve found doing historical research for your work?

Emily: Honestly, I think for me the most surprising thing was realizing just how much we actually know about ancient women, just how much research there actually is. Embarrassingly, I hadn’t read extensive scholarship on women’s history during college and graduate school because it wasn’t part of the core curriculum. I didn’t know all that was there until I began looking intentionally.

My introduction must have been in my final semester of seminary, when I took an elective on women in contemporary African Christianity and audited another class on medieval women, and those started to crack open the doors. Then, once your foot is in and you find, say, one article with robust footnotes, you can start following the trails. There are so many dedicated scholars unearthing stories and clues about pre-modern women through innovative detective work. The trails are rich and never-ending, and we’ve gotten to explore some for our podcast. I suppose that becomes the lesson –which, come to think of it, also applies to other areas of life– you have to choose to look.

Rebekah: Piggybacking on that, as an academic I find myself reading for things that I’m interested in, that intersect with my research on violence and ritual. If you’re not looking for women, it’s easy to overlook them. But, once I started thinking about questions of gender, especially once Emily and I had started the podcast, I started looking. Now as I’m doing my research, if I see a reference about a woman performing a ritual, I’m going to jot that down and go read about it. Because now that I am paying attention to women, I’m seeing texts and scholarship all over the place, usually in the footnotes. The surprising thing is that there are a lot more women than I thought there were.

It’s my sense, both from my students and also my own college experience, that learning about women in history is often regulated to a gender studies or topical class on women. You might get a course about women and magic, or women and sexuality. Or, perhaps women will appear as a topic for one week on a syllabus, or there might be a reading or two dedicated to them in a course otherwise dominated by historical men. I think we need to move beyond this tendency in academia to check boxes when it comes to teaching about ancient women or to limit student interest in women to certificate programs. Stop putting women in the footnotes.

Something one of our earliest podcast guests said has stuck with me, which is this concept of above and below the line in academic writing. Above the line is what’s written in the body of your paper, article, or book. This tends to be your thoughts and the thoughts of those you perceive to be the big name scholars – the people whose work you know really well. Everybody else goes below the line, in the footnotes. These conventions about which scholars “really matter” create a self-perpetuating cycle, so that other scholars (often women) keep getting relegated to the footnotes. This concept of above and below the line is really helpful for thinking about where we need to go with women’s history and research about women. There’s so much great work being done about women in the ancient world, but it often goes overlooked. It’s still “under the line” in some sense. So it is not enough to start paying attention to women, we need to actively put them above the line. Which is what Emily and I try to do in our podcast, Women Who Went Before. We’re taking all this amazing research and making it more accessible to people who might not be hanging out in academic libraries trying to write a dissertation.

Emily: Or who lack a subscription to JSTOR! Many people might not have access to academic journals or research libraries, but they definitely are interested in learning about history and its women. That’s where podcasts, blogs like yours, radio programs, TV series, historical fiction, video games, and more creative public scholarship come into play. And I’ll add lastly, it’s not just what scholars say and where, but also how we say it. To truly be accessible we need to communicate academic research and writing in emotive and engaging ways.

A question from Rebekah and Emily: What historical woman would you want to go back in time and meet, and how would you spend the day with her?

My first thought on reading this question was: So many women! How can I possibly choose?

My second thought was: Queen Wilhelmina of the Netherlands. Wilhelmina ascended the Dutch throne in 1898 at the age of 18. She was sixty when Nazi Germany attacked the Netherlands. She transformed herself from a stiff, shy, distant ruler to the heart of her country’s resistance. Hours after the German attack began, she made her first broadcast against the Nazis on Dutch radio. She made her next broadcast the day after she arrived in Britain. Every day thereafter, the the queen spoke to her people at the start of the Radio orange program broadcast to the Netherlands by the BBC. Her radio speeches were passionate and personal; with one exception, she wrote them herself. The Dutch joked that the queen’s grandchildren weren’t allowed to listen to her broadcasts from their refuge in Canada because she used such foul language when she talked about the Nazis.

As far as what we’d do: given my current project I’m in the mood to kick back and trash talk the Nazis over a dark beer.

Want to know more about Women Who Went Before?

Listen to the podcast: https://womenwhowentbefore.com/

Follow them on Twitter: https://twitter.com/womenbefore

Check out the podcast Facebook page: https://www.facebook.com/womenbefore

***

Come back tomorrow for two questions and an answer with biographer Eleanor Fitzsimons

March 13, 2023

Talking About Women’s History: Three Questions and an Answer with Leah Redmond Chang

Leah Redmond Chang is a former Associate Professor of French literature and culture at The George Washington University. Her writing draws on her extensive experience as a researcher in the archives and in rare book libraries. Previous books include Into Print: The Invention of Female Authorship in Early Modern France, which focused on women and book culture in the sixteenth century, and (with Katherine Kong) Portraits of the Queen Mother, about the many public faces of Catherine de’ Medici. Her next book, Young Queens: Three Renaissance Women and the Price of Power, will be published by Bloomsbury in the UK (May 2023) and Farrar, Straus and Giroux in the US (August 2023). She lives with her husband and three children, and divides her time between Washington DC and London.

Take it away, Leah!

In your coming book, Young Queens, you write about three fascinating women. Do you have a favorite among them?

Not an easy question! Young Queens follows the intertwined lives of three sixteenth-century women: Catherine de’ Medici, her daughter Elisabeth de Valois, and her daughter-in-law, Mary Stuart, also known as Mary, Queen of Scots. I like them all for different reasons, but if pressed, I would have to say that Catherine de’ Medici is my favorite. She has an unfair advantage in some ways: Catherine was the power behind the French throne until her death in 1588 at age sixty-nine, whereas her daughter Elisabeth died young at twenty-two years old. Mary, Queen of Scots, as many people know well, fled Scotland at twenty-five only to become the prisoner of Elizabeth I of England. Her imprisonment lasted until her death, at forty-four, in 1587. Perhaps it’s easier for me to like Catherine because she lived the longest and moved around the most, filling many different roles during her lifetime. She also wrote thousands of letters, so we have an incredibly rich record of her life and policies. And yet, she remains less known than a woman like Mary, Queen of Scots. That intrigues me.

Catherine was always a little bit of an underdog – and I love an underdog. An orphan practically from birth, a ‘commoner’ in the eyes of the French nobility, the unloved bride of a second son – certainly as a young woman, she seemed unlikely to become so powerful. Yet it’s the adversity Catherine faced in her youth that made her strong. Catherine was a survivor, unlike Mary, Queen of Scots who, although the ‘it’ girl at the French court during her adolescence, didn’t possess Catherine’s grit. To be fair to Mary, though, in some ways she was set up to fail, and had little reliable support once she returned to Scotland at the age of eighteen. And she made such bad choices. Could she have avoided them? Every time I retrace her story, I kind of wish she could have.

I’ve often wondered what Elisabeth de Valois would have become had she lived beyond the age of twenty-two. She was very close to her mother, and Catherine had trained Elisabeth well. It was clear by Elisabeth’s teen years that she had the talent to develop into a canny political player. The tragedy, from a historian’s perspective, is that she didn’t live long enough to see it through. That she died trying to fulfill a queen’s first duty: to provide an heir for the kingdom. And that she suffered so much trying to be both a good wife and good daughter, queen of one kingdom and royal princess of another.

You can probably sense me weighing my answer here – even as I type this, I’m running through the lives of these women, assessing what appeals to me about them. In the end, though, I still return to Catherine. She was such a complex woman, and her legacy is equally complex. She’s always had a notorious reputation despite the many efforts by scholars to recuperate her image and reveal her astute political mind. From my first encounters with Catherine, I was a bit suspicious of that ‘bad girl’ image. But Catherine wasn’t exactly an innocent victim of baseless calumny, either. She had strengths and she had weaknesses; she did both good and bad things. In short, she was a real human being, with all the baggage that comes from being human. I think that’s what I love about her: in her complexity, Catherine allows us to see the real woman behind the crowned queen.

You are writing about women who were powerful and well-known in their own time. Are there special challenges in researching such women?

There are several challenges, but I’ll focus one here. I consistently run into the problem of reliable evidence. Sixteenth-century Europe was awash in propaganda. A lot of social dynamics and tensions in the sixteenth century will seem familiar to those of us living in the twenty-first: countries torn apart by civil strife, a hardening ‘right’ and ‘left’ with diminishing hopes of breaching the divide, the rapid growth of new technology and media that enabled voices to proliferate in the public sphere, something akin to religious ‘wokeness,’ and many misogynist voices raised against women in power. These are exactly the conditions that encourage the amplification of fake news, especially about a woman who wields any kind of authority. So how do you get to the ‘truth’?

Catherine de’ Medici and Mary Stuart were both fervently adored and deeply despised during their lifetimes. Years ago, when I first started working on Catherine de’ Medici, a scholar warned me that there is no objective account of her. I found this largely to be true: it is very hard to parse fact from fiction both in sixteenth-century sources and in those produced during the centuries that have followed. To a certain extent, the same can be said of Mary. I think any book on either of these queens has to take a historiographical stance: how are you going to tell this story? How does one do justice to these women who have so many ‘lives’ in the sources? Who have taken on such mythical proportions in the cultural imagination that it’s easy to lose sight of them as living, breathing human beings?

Elisabeth de Valois is a slightly different story. She was beloved by her kingdom. No one had anything bad to say about her. But this too can become a problem. Everyone loved her a bit too much – the praise can become a little inflated. Luckily, we have sources that do give us a more rounded, intimate portrait of her – my favorites are letters and accounts by her ladies-in-waiting. And from those letters we also catch a glimpse of Elisabeth’s inner life.

That said, the letters by the ladies-in-waiting were difficult to wade through. Elisabeth was well-educated for a noblewoman in her day; her ladies weren’t always. The spelling! Oh, the spelling! As it was, sixteenth-century French spelling wasn’t codified. But these ladies often spelled phonetically. Sometimes it took me several passes through the letters to figure out what they were saying at all, let alone analyze the nuances of it.

How would you describe what you write?

I write narrative history, with an emphasis on ‘narrative.’ The two books I wrote before Young Queens were quite scholarly, and I really enjoyed researching and writing them. But I’ve always been interested in writing narrative history and exploring how scholarship could be brought to readers through story.

Growing up, I loved history, and I loved fiction. I especially loved books that blurred the line between ‘history’ and ‘fiction’ (as a child, I was obsessed with the ‘Little House’ series for that reason). I still remember my history teacher in 9th grade: at the start of every class, Ms. Smith would come out from behind her desk, perch herself on the edge, and tell us a story. That was her entry into the material, and I would always bring those stories home to the dinner table. In college, I majored in an interdisciplinary program that focused on history, literature, and philosophy, and when it came time to apply to graduate school, I ended up applying to PhD programs in both history and comparative literature. Eventually, I decided to go with comparative literature with the rather naïve idea that I could work in both disciplines under that umbrella. Although that wasn’t entirely the case, comp lit did allow me to think outside of traditional disciplinary boundaries.

As a literature scholar, I have always been very archival in my research. I’ve always wanted to handle the objects of the sixteenth century and to use them to understand the culture and the people. Though I’ve left the university in an official capacity, I’m still archival, but now I’m more focused on trying to capture the inner lives of the people I study and translate those lives to the page. I try to think about story arc and about historical actors as characters. I also like the challenge of working with and around historiographical limitations: how do you create scene and story when you must respect what the archive gives you? To me, that question makes the whole endeavor exciting. I guess you can say that I love the craft.

(They’re both so pretty! )

A question from Leah: Across your books, you cover a lot of ground both geographic and temporal. How do you land on your subjects? What makes you say ‘Yes! This is the woman / women I’m going to write about’?

There is no simple answer to that.

In the case of Women Warriors, the general topic caught my imagination at an early age but I didn’t start thinking about it in an orderly way until years later, when Antonia Fraser’s Warrior Queens came out. After that, it seemed like I ran across examples of historical women who fought everywhere and I started to collect their stories in a casual way. When it was time to write the book, I had hundreds of examples, and I continued to find more as I worked on the book. At that point, it was a matter of making hard choices because I wanted women from different times and different places and who fought for different reasons.

For my current book, the subject literally turned up in my news feed and wouldn’t let go of my imagination.

Ultimately, I think subjects find me.

***

Want to know about Leah Raymond Chang and her work?

Check out her website: leahredmondchang.com

Subscribe to her newsletter: leahredmondchang.substack.com (Consistently interesting <

***

Come back tomorrow for three questions and lots of answers with the women who host the Women Who Went Before podcast.

March 10, 2023

In which I finally read “A Woman of No Importance”

Earlier this month, I was called to jury duty. I must admit, I thought about trying to get out of it on the grounds that I am under deadline on this book.* But I just couldn’t do it. I believe in the importance of the jury system. And I have spent the last few years thinking about the destruction of of the rule of law in Nazi Germany. So, I grumbled about the loss of a day. I prayed that I wouldn’t end up on a jury and lose more than a day. And I thanked the powers that regulate civic duty that I was assigned to a downtown court instead of one in the distant suburbs.

All of which is a long lead-in to the fact that I decided l Sonia Purnell’s A Woman of No Importance: The Untold Story of the American Spy Who Helped Win World War II was the perfect thing to read in the jurors’ waiting room. The subject was adjacent to what I’m working on, but not so close that I needed to take notes. And by all accounts, it was a gripping read.

I am, as is so often the case, late to the game. Many of you may have already read Purnell’s bestselling account of Virgina Hall,** the American woman who talked her way into Britain’s Special Operations Executive (SOE) and was the first Allied woman deployed behind enemy lines—prosthetic leg and all.

A Woman of No Importance is a fascinating biography, with the tone of a thriller. Purnell starts with Hall as, in fact, a woman of no importance who had opted out of the life of a Baltimore socialite and been repeatedly frustrated in her attempts to join the diplomatic corps as more than a secretary. She traces Hall’s unlikely acceptance by SOE—in large part because the newly formed agency was desperate—and her invisible rise as a covert operator working with the French resistance in spite of repeated bumbling and failures on the part of SOE.

Because these days I read narrative non-fiction from a writer’s viewpoint,*** I was struck by the skill with which she weaves the larger story of World War II into Hall’s story. She consistently gives the reader the information they**** need, without dumping a chunk of information that disrupts the story line. It is harder to do than you might think.

If you’re interested in World War II, spies, spies in World War II, or forgotten women who did amazing things, this one’s for you.

*Probably not a valid excuse, now that I think about it.

**After all, lots of people reading (or at least buying) a book is what makes a book a best-seller.

***A habit I hope to ditch after I recover from writing the current book. It may require serious rehab involving sitting on the rear deck with a pitcher of ice tea, a stack of really well-written books, and no way to make notes in the margins.

****I hear some of you screaming and getting ready to send me emails about this usage. The big style manuals all gave their blessing to the use of they as an indefinite singular pronoun several years ago. If it’s good enough for the Chicago Manual of Style, it’s good enough for me.

* * *

Come back on Monday for three questions and an answer with historian Leah Chang.