Pamela D. Toler's Blog, page 35

November 15, 2022

The Pirate’s Wife

A title like The Pirate’s Wife makes promises to the reader: adventure, danger, betrayal, romance, and especially pirate treasure. Daphne Geanacopoulos* more than keeps those promises in this deeply researched and richly imagined exploration of the life of Sarah Kidd,** the little known wife of one of history’s most infamous pirates.

Sarah’s marriage to Captain William Kidd stands at the heart of the book. Daphne tells the story of Kidd’s betrayal by his [non-pirate] business partner, capture, trial, and execution through the lens of Sarah’s experience of them. She discusses the world of pirates, the fine line between piracy and privateering, and the fact that being a pirate’s wife is not the same thing as being a female pirate.

And yet their marriage was only a short part of Sarah’s life.

Daphne uses a wide range of records to piece together the life of a woman who, like many women of her time, could not read or write and consequently could not leave her own account of her experiences. She demonstrates how Sarah reinvents herself across multiple changes in fortune and through four very different marriages at a time when a woman’s place in society was determined by that of her husband.*** (Captain William Kidd was her third marriage and the only one that was a love match.) I was particularly fascinated by her period as a successful “she-merchant”: with her first husband’s support**** she opened a shop where she sold high-end imported goods.

The end result is not only the previously buried story of one woman’s life—in itself a form of hidden treasure–but a detailed and sometimes surprising picture of women’s lives in colonial America.

If you’re interested in pirates, women’s history, or colonial America, this one’s for you.

*Who I am going to refer to as Daphne hereafter, both because we are writing friends and also because otherwise I will undoubtedly misspell her last name at least once.

**Who I am going to refer to as Sarah hereafter, because historians have attached Kidd to her more famous husband for a long time.

***A woman did not have a legal identity separate from her husband. She was literally his property, though not in the same way that a slave was property. (More than once, Daphne pauses to look at the role of slaves in Sarah’s life during her marriage to Kidd—powerful reminders that slavery was already embedded into American culture at the end of the seventeenth century.)

****See *** above. Without his support she could not have taken any of the legal or financial actions needs to open and run a business.

November 8, 2022

The Thrill of the Vote

This post first ran on election day in 2008. My feelings on the subject haven’t changed:

It’s election day in Chicago. I just walked home from voting for a new mayor and a new alderman–and I miss my old neighborhood.

For ten years I lived in South Shore: a white graduate student/small business owner/writer in a neighborhood dominated by the African-American middle class. My neighbors were police officers, schoolteachers, fire fighters, electricians, and social workers. We didn’t have much in common most of the year–except on election day.

As far as I’m concerned, voting is thrilling. My South Shore neighbors agreed. Voting in South Shore felt like a small town Fourth of July picnic. Like Mardi Gras. Like Christmas Eve when you’re five-years-old and still believe in Santa Claus. No matter what time of day I went to vote, my polling place was packed. Voters and election judges greeted each other–and me–with hugs, high fives, and “good to see you here, honey”. First time voters proudly announced themselves. Elderly voters told stories about their first election. People made sure they got their election receipts; some pinned them to their coats like a badge of honor. An older gentleman sat next to the door and said “Thank you for exercising your right to vote” as each voter left. The correct response was “It’s a privilege.”

Except for occasional confusion when the machine that takes the ballots jams, my current polling place is low key. Election judges are friendly and polite, but hugs are not issued with your ballot. When the young woman manning the machine handed me my receipt, she told me to have a good day. I said “It’s always a good day when you get to vote.” In South Shore, that would have gotten me an “Amen.” In politically active, politically correct Hyde Park, it got me an eye-blinking look of surprise and a hesitant smile.

I started home, thinking maybe I was the only one in the neighborhood whose pulse beat faster on election day. A block from the polls I ran into a young man walking with a small boy, no more than six years old. The little boy stopped me, with a grin so big that he looked like a smile wearing a woolly hat.

“Did you vote yet?” he asked. “My dad is taking me to teach me how to vote.”

“It’s a privilege,” I said.

He gave me the highest five he could manage.

* * *

That little boy is old enough to vote now. I hope he went to the polls in today’s mid-term elections with the same enthusiasm he showed then. I know I did. It is indeed a privilege.

So tell me, did you exercise your right to vote?

November 4, 2022

From the Archives: You think one vote doesn’t matter? Hah!

I have told this story here on the Margins before. But with the midterm elections only a few days away, I think it’s important to remember right now that in the end the 19th Amendment was ratified thanks to one man’s vote.

In August, 1920, 35 states had ratified the amendment; 36 states were needed for it to pass. Tennessee was the only state still in the game. Proponents and opponents of the amendment gathered in a Nashville hotel to lobby legislators. The press dubbed it the War of the Roses because supporters of the suffrage movement wore yellow roses in their labels while its opponents wore red roses.

On August 19, the vote appeared to be tied, assuming the count of red and yellow roses was correct. When the roll call came, 24-year-old Harry T. Burn stepped into history. Burn came from a very conservative district and wore a red rose in his label, but when asked whether he would vote to ratify the amendment he answered “aye”. What changed his mind? A letter from his mother, Febb Burn, who told him to “be a good boy” and vote in favor of the amendment.

Asked later about his change of heart, Burn said “I knew that a mother’s advice is always safest for a boy to follow and my mother wanted me to vote for ratification. I appreciated the fact that an opportunity such as seldom comes to a mortal man to free 17 million women from political slavery was mine.”

If you have the right to vote, use it. Because one vote can in fact change the world.

November 1, 2022

From the Archives: You Can’t Vote Because….

If you’ve been hanging around the Margins for a while, you’ve read this one before. I think it’s worth repeating.

From sixth century Athens on, who has the vote and why has been a touchy and evolving subject in democracies. People who already have the vote have hesitated to extend it to others for two basic reasons. Those with the vote don’t think those without the vote have the capacity to make good choices. Those with the vote fear they will lose power.

Over the centuries, people in power have come up with plenty of reasons not to extend the franchise to those who don’t yet have it. Here are a few of the classics:

You can’t vote because

You’re a slaveYou’re a womanYou don’t own propertyYou don’t own enough propertyYou don’t practice the right religionYou are the wrong race or ethnicityYour father or grandfather couldn’t voteIf you’re lucky enough to have the vote, use it.

October 25, 2022

Sister Novelists

Recently I was talking with a group of writer friends about the question of accuracy in historical novels and movies. It was an intense discussion that began with The Woman King* and ultimately found its way to the film adaptations of Jane Austen’s movies. In the course of that discussion, I heard myself saying “That’s something Jane understood in her bones.” Then I stopped and said “Or perhaps I should say Miss Austen. I don’t think I’m on a first name basis with Jane Austen.”

Except, of course, reading and movie-watching women today can be said to have an intimate relationship of sorts with Miss Austen. We have read her books (sometimes multiple times) and watched the countless film adaptations. We have enjoyed films like Clueless and Bride and Prejudice, which take the plots of Austen novels, and sometimes even their lines, and place them in contemporary settings. And in recent years, a sub-genre of novels that do the same thing has gained popularity. I am not a hard-core Austenite, but she is part of my cultural DNA.

Jane Austen is often treated as a stand alone literary figure, followed a generation later by the Brontë sisters. (We should know better by now. The field of women doing anything at any point in time is always deeper than the story we’ve been told.) In Sister Novelists:The Trailblazing Porter Sisters, who Paved the Way for Austen and the Brontës, literary historian Devoney Looser introduces us to Jane and Anna Marie Porter, contemporaries of Austen’s who were best-selling novelists and literary lions. (Napoleon banned Jane Porter’s books.) They also created a new literary genre: the historical novel.**

Using the thousands of letters the sisters left behind, Looser tells the story of their rise to fame, their financial struggles, their social successes, their romantic failures, and the eternal Catch-22 of being successful single women in a society that had no clearly defined space for such women. The result is a gripping work of impeccable scholarship.

If you’re an Austen fan, or interested in trailblazing women in earlier times, this one’s for you.

* And speaking of The Woman King, if you are interested in learning more about the history surrounding the movie, I strongly recommend this self-study syllabus put together by a trio of historians with deep credentials on the subjects of the slave trade and African history: https://womankingsyllabus.github.io/

**Their childhood friend, Sir Walter Scott, was inspired by their work and history has subsequently given him the credit. This should surprise no one who has spent anytime looking at forgotten women in history, but I must admit it broke my heart—just a little. I developed a bit of a fan-girl crush on Sir Walter while writing my dissertation. I’m disappointed in him.

October 18, 2022

History and “A More Just Future”

Last December, My Own True Love and I stopped in Saint Louis on our drive from Chicago to my hometown in the Missouri Ozarks. We spent two hours at the Gateway Arch. The museum at the base of the arch had been completely renovated since our last visit, thirteen years previously. I was delighted to see that the story of westward expansion had been, well, expanded. Women and people of color were explicitly included,* as was the United States’ agressive actions against Native Americans in general and against Mexico in the 1840s. The exhibit told the story of lost rights and imperial actions alongside stories of material progress, courage, and growth.

I talked about the changes in the way the National Park Service tells the story in some detail in a blog post about our visit. What I didn’t share in that post was the way the exhibits made me feel. By the end of that two hours, my head throbbed, my stomach hurt, and my heart ached. Holding the two stories side-by-side was painful. History is my passion. But over the last few years, I’ve also learned that history is hard. And I’ve come to believe that it should be.

Which brings me to Dolly Chugh’s new book, A More Just Future: Psychological Tools for Reckoning with Our Past and Driving Social Change. Dolly deals directly, and brilliantly, with the discomfort increasing numbers of us are trying to come to turns with about the disjunction between the history we were taught and the history we weren’t taught. Her goal is to help us, and herself, “appreciate both the reality of our country’s mistakes and the grandeur of our country’s greatness”—a condition she defines as being a “gritty patriot”—and further, to understand the impact of our past on our present.

Dolly is a social psychologist, not a historian, so the focus of her book is not on the buried/forgotten/overlooked tales of our past,** though she uses some of those stories to illustrate her points. Instead she helps the reader understand why is it so difficult, emotionally and intellectually, to unlearn history—as individuals and as a country—and gives her (and by her, I mean me) tools for doing so.

A More Just Future is an important and wise look at confronting our whitewashed history and the emotional impact of doing so. It is also a delight to read. Trust me on this.

* A trend you’ve seen me applaud many times in these posts and in my newsletter over the last few years.

**Or more accurately, the stories left out of mainstream accounts of our collective history.

credit-Jeanne Ashton

Just so you know: Dolly Chugh is a Harvard-educated, award-winning social psychologist at the NYU Stern School of Business, where she is a expert researcher in the psychology of good people. In 2018, she delivered the popular TED Talk “How to let go of being a “good” person—and become a better person.” She is also the author of the acclaimed book The Person You Need to Be and the popular newsletter Dear Good People. [Both of which I strongly recommend.]

You can find out more at DollyChugh.com.

October 11, 2022

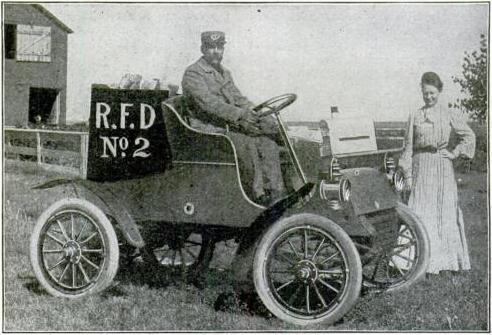

Rural Free Delivery

Every time we take a road trip, we miss one or two or twelve things we would like to see because they were closed for the season,* or we hit town on the wrong day, or we had the wrong directions,** or we just plain ran out of steam.

In the case of the Rural Free Delivery Postal Museum, in Morning Sun, Iowa, we made an attempt to set up an appointment, but the telephone number on the website was dead. And it was a little too far out of our way to take a chance and just stop by.

But the story the museum celebrates is just too good not to share:

Home mail delivery is something we take for granted in the United States .*** But in fact, it is a relatively new service. Free mail delivery began in cities in 1863. Rural postal customers—who made up the vast majority of the population at the time— weren’t so lucky. They paid the same amount for stamps as city folk, but they still had to pick up their mail at sometimes distant post offices or pay private companies to deliver it.

In 1896, after several years of advocacy by the National Grange**** and discussion by Congress, Postmaster General William L. Wilson agreed to test the idea of Rural Free Delivery. The service began on October 1, 1896, when five men on horseback set out to deliver mail along ten miles of mountain roads outside Charles Town, Halltown, and Uvilla West Virginia. (Perhaps it was not by chance that West Virginia was Wilson’s home state.) Within a year, the post office serviced 44 routes in 29 states. (The service was so new that regulation mailboxes did not exist. Farmers nailed improvised receptacles on fence corners, including old boots, tin cigar boxes, and shoe boxes.) Customers across the country sent more than 10,000 petitions asking for local routes.

In 1902, Rural Free Delivery became a permanent service of the Post Office. Farm families became a little less isolated.

On a related note: The RFD Museum wasn’t the only postal moment on our trip. When we stopped at the Pine Creek Grist Mill in Muscatine County, Iowa, we learned that the gentleman who founded the mill in 1834 was licensed to run the first post office in the county. The mailing address for any letters coming through the post office was the same: Iowa Post Office, Blackhawk Purchase, Wisconsin Territory. I had never thought about how letters would be addressed on the frontier. Suddenly it became clear to me just how amazing it was that people could send letters to someone who had left home and moved west.

*Word to the wise: If you take a road trip through Minnesota in late September you will miss a lot of stuff.

**As I mentioned in an earlier post, if you want to visit the New Philadelphia archeological site, do NOT put New Philadelphia, Illinois in your GPS. It will take you to an existing town in the other direction.

***Or at least we did until recently.

****For those of you who don’t know: The National Grange of the Order of Patrons of Husbandry, commonly known as The Grange, has been providing support for American farmers since 1867. Originally designed to help rural America recover from the devastation of the Civil War, “Grangers” fought discriminatory railroad pricing, established local buying cooperatives, and, yes, fought for rural mail delivery. Local Grange Halls were often the social heart of rural communities places and worked with Farm Bureaus, Extensions Services and 4-H clubs to educate farm families about the newest methods of farming and household management. Today the Grange is still an active advocate for family farms. Cooperative action at its best.

October 4, 2022

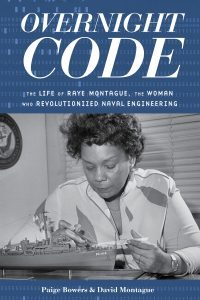

From the Archives–Overnight Code: A Q & A with Paige Bowers

Overnight Code, Paige Bower’s fascinating biography of groundbreaking computer engineer and ship designer Raye Montague, is being released in paperback today, which makes this a good time to bring this interview out of the History in the Margins archives. If you’re interested in women’s history in general, women in STEM in particular, Black history, the history of computers or ship building, this one’s for you.

*****

I’ve been waiting to read Paige Bower’s Overnight Code ever since Paige announced the deal more than a year ago. When I finally got my hands on it, the book more than lived up to my expectations. Overnight Code is an important addition to the growing genre of works that give voice to important and largely forgotten women of science. It is also a powerful and inspiring story of a woman who refused to be stopped by the dual challenges of racism and sexism in the largely male, largely white world of the early days of computer science.

I am pleased to have Paige back here on the Margins to talk about the book and how she wrote it.

How did you come across Raye Montague’s story? Was your experience of writing her story significantly different that writing about Genevieve De Gaulle, who was the subject of your previous book?

My agent saw Raye on a “Good Morning America” segment and approached her about writing her memoir, which had been something people had been telling her she needed to do for a long time. Her son, my co-author, David, was going to help her write it, but one thing led to another and my agent approached me about getting involved. I was a huge fan of Hidden Figures, so the opportunity to help Raye tell her little-known story was really appealing to me. Unfortunately, she passed away right as the proposal for her book found a home, so I went from working with her on her memoir, to working with David on what would become a biography. The experience was significantly different from my previous book for a variety of reasons: 1. I actually had the opportunity to interview Raye, which was not possible with Genevieve de Gaulle, who had long since passed before I thought to write her about her. So that helped me get more of a sense of who Raye was, how she spoke, what her personality was like, and so forth; 2. David was a fantastic partner in this because he very generously mailed me his mother’s personal papers, dug up people for me to interview, and was a constant sounding board from beginning to end; and finally 3. I’m typically a pretty anxious person, but when I sent this off to my editor, I was far more at peace with the end result of this book than I was with my first. David and I are very, very excited to introduce his mother to readers!

Overnight Code straddles the boundaries between memoir and biography. How did you navigate that?

You know, I hadn’t really thought about that until now! I suppose it worked out this way because in the beginning it was supposed to be a memoir, and I spent a lot of time listening to Raye tell stories, and was doing what I could to capture her cadences and her indomitable personality on the page. After she passed, I knew the writing voice needed to shift, and there needed to be more reporting and research to counterbalance what she said. By the same token, I didn’t want to let go of the fiery spirit that I had begun to capture. It is what made her so beloved by so many people, and I felt like it was what was driving the narrative chapter to chapter, making events from decades ago still feel so alive and fresh.

There is a significant STEM component to Raye’s story, but you make it easy for a non-technical reader to understand. How much did you have to learn to about the technical aspects of her story? And how hard was it? ( I assume you didn’t already have a background in early computers and ship design.)

Dirty little secret: I was not the best math and science student, so I realized that learning about early computers and ship design was the first and most important thing I needed to do. It was a pretty steep learning curve. I had a general idea of the early computer part, but I was able to interview Raye about her experience, as well as some of her former colleagues to get more detail about how that technology worked. David sent me some of his mother’s books about ship design, so that helped me get a better sense of how it developed over time, and how computers were brought in to make the process faster and easier. I interviewed another former colleague of hers to fill in some of the gaps, and he was so good, and made things so clear to me, I felt confident that I could write about it in a way that was easy to understand. [Pamela here: She succeeded.]

You do an excellent job of placing Raye’s story in the context of both the civil rights movement and the women’s movement in the late 1960s and early 1970s. Did anything about her experience of discrimination take you by surprise, or particularly outrage you?

Thank you! She was definitely an extraordinary woman living through an extraordinary moment. I am not sure if I was surprised by her experiences with discrimination, but I was certainly disgusted with the ways in which she was treated with such disrespect because of her color and gender. The saddest part about it is that she went back to be honored by the navy maybe a decade or so after her retirement, women told her that they were still experiencing some of the discrimination she faced.

One of the questions I’m fascinated with right now is how biographers name their subjects, particularly when writing about a woman. Can you explain why you chose to use Raye’s first name throughout the book?

I think a lot of it boils down to intimacy. I wanted readers to feel close to and be on a first name basis with this little-known woman who lived a big, bold life. But I also think it speaks a bit to Raye, who didn’t want to be called Mrs. Montague, or for me to “Yes ma’am” her. She wanted to be known as Raye, and as a person, not a gender. It was difficult for me to get my head around that when I first began interviewing her. My Southern mama raised me with some pretty old school manners. But from the outset, Raye told me to call her “Raye,” and in doing that, she pulled me close and told me all about her life and times. It was a tremendous honor, one I’ve never taken lightly.

What would you like readers take away from the book?

David and I want people to be inspired by this woman who followed her dreams and didn’t take no for an answer. Having your dreams come true is no straightforward, fairy tale thing. It involves preparation, determination, occasional heartbreak, shifted gears, and ultimate triumphs. Persistence is key. So is resilience. Just look at Raye’s life and you’ll have all the proof you’ll need!

Paige Bowers is a journalist and the author of two biographies about bold, barrier-breaking women in history.

For the past few years, Paige has worked closely with Hidden Figure Raye Montague’s son, David, on the story of how his mother engineered her way out of the Jim Crow South to become the first person to draft a Naval ship design by computer. That book, OVERNIGHT CODE: The Life of Raye Montague, the Woman Who Revolutionized Naval Engineering, was published by Lawrence Hill Books on January 12, 2021.

Her first book, THE GENERAL’S NIECE: The Little-Known De Gaulle Who Fought to Free Occupied France, is the first English-language biography of Charles de Gaulle’s niece, confidante, and daughter figure, Genevieve, to whom he dedicated his war memoirs. It’s the story of a remarkable young woman who risked death to become one of the most devoted foot soldiers of the French resistance, and later became a public figure in her own right.

Paige is a nationally published news and features writer whose work has appeared in TIME, USA Today, The Wall Street Journal, The New York Times, People, Allure, Glamour, Pregnancy, The Atlanta Journal-Constitution, Atlanta Magazine, Aventura, and Palm Beach Illustrated. Paige lives in the Atlanta area with her family, which includes a Yellow Lab who believes he is a lap dog.]

Want to know more about Paige Bowers and her work?

Check out her website: http://www.paigebowers.com/

Follow her on Twitter: @paigebowers

September 30, 2022

Emily Bliss Gould: An American in Italy–A Guest Post by Etta M. Madden

Etta Madden, who is also an American in Italy whenever possible

Etta Madden is Professor of English at Missouri State University and the author of Engaging Italy: American Women’s Utopian Visions and Transnational Networks (SUNY Press), Eating in Eden: Food and American Utopias (U Nebraska Press) and Bodies of Life: Shaker Literature and Literacies (Greenwood). She has also published numerous articles on American literature and intentional, spiritual communities in the US and in Italy.

In addition to receiving a Fulbright award, she has been a research fellow at the New York Public Library and is a two-time recipient of Mellon fellowships from the Library Company of Philadelphia.

Take it away, Etta!

Emily Bliss Gould with Venetian Bartoli children, from Italo-American Schools at Rome [1874], New-York Historical Society. Credit: Photography ©New-York Historical Society.

Not all women warriors fight with swords and spears. Emily Bliss Gould, a US expat in Italy, waged warfare with her pen. She picked her battles carefully, and she engaged clever rhetorical tactics.Gould went abroad in 1860 with her husband, retired US Naval physician James Gould. The story is that they went to Italy for her health, but his retirement followed leadership changes and likely factored into their decision. He soon became the recommended physician for US expats in Rome, according to travel guides such as John Murray’s A Handbook of Rome and its Environs (1867). Emily was not merely a trailing spouse when she went abroad in her mid-thirties She found a cause to fight for when she first witnessed schools in Italy’s Piedmont region. The work of the Waldensians—non-Roman Catholic Christians whose history predated Martin Luther—impressed her. The Waldensian schools in rural mountain villages around Turin served impoverished children, and Gould (like many others) believed education would benefit them dramatically. She wanted to see more of such good work.

In 1867 Gould picked up her pen to join the forces for better education. She wrote in December from Florence, Italy, in the dining room of the US Ambassador, George Perkins Marsh and his wife Caroline. Her chosen battle? Finding funds to support the Florence Evangelical School, “a school of some 200 or 300 children.” She wrote to Dr. Thompson, President of the American Foreign and Christian Union, begging with all the metaphors she could muster. Gould employed the language of agriculture rather than warfare, plowshares rather than swords. “We must educate future regeneration of the land,” she wrote. By land, she meant the people, instead of the peninsula’s depleted soil. The children possessed promise. And because Florence was “now open to religious and intellectual improvement,” she wrote, US citizens might help.

In 1870, and with the funds she had raised, Gould had moved south to Rome. There she established what became known as the Italo-American Schools. These provided housing and were orphanages as well as industrial schools—that is, schools that taught hands-on skills rather than classical literature. All the students learned basic literacy and math, but additionally, the boys learned typesetting and printing, while the girls learned needlework. (Gould did not have a problem with this gender division). Like many privately-funded schools, the education also included some pointed messages regarding political and religious beliefs. Children learned patriotic songs and bible stories. But Gould’s overall stated purpose with the school efforts were, along with literacy, skills that might help young people earn a living–what today is called “workforce development.” As she explained, it was “to christianize and civilize, not to propagandize.” Not surprising, what she hoped would be unifying work for the good of all was divisive.

Wherein, beyond financial support, lay the battles?

One, to be expected, was with Roman Catholics who saw Gould’s work as threatening. But more significant, as her successes grew, Gould realized a few non-Catholic men were trying to wrest control from her. This new warfare with words erupted in Gould’s private letters, rather than on any public stage. She expressed her frustration to Ambassador Marsh that one Italian male leader misspent funds—he needed to learn the ABCs of finance. And in another, she wrote that a certain church leader wanted to oversee not only the organization but also—surprise, surprise!–all the funds she raised for it, by putting it “under the charge of” the American Sunday School Union. Her fiery words about this individual (beyond the scope of this blog post), elicited a strong response from the Ambassador. Marsh, in agreement, referred to this “altar man” as an “ass.” Marsh seems to have been an ally, but there is no evidence that he fought on her side. We can only imagine that his words and their ongoing correspondence indicate at least emotional support.

What we do know is that as Gould’s work continued, her voice in the annual reports and fundraising letters grew stronger. Initially, her words were subsumed by the male board of directors. Gradually, her name and words appeared less-obliquely within the reports. In fact, in the last report before her death in 1875, Gould wrote directly with an appeal to readers, even signing her name as “Directress of the Italo-American Home and Schools.” This culminating publication included a portrait—albeit not of Gould dressed in armor and on a horse ready for battle but rather posed as a gentle mother figure. She holds in her lap two Venetian children, Marietta and Bepino Bartoli. This public posture counterbalanced her private aggressiveness.

The other private battles with “Mrs. Gould’s Works and Wants” (as one annual report of the Italo-American Schools was subtitled) engaged Waldensians. These insiders to the language and culture, also experienced with running schools, had helped her mission; she had collaborated with them for several years. Communications with Matteo Prochet, longstanding President of the Evangelism Committee and linguistically adept (he knew multiple languages and traveled throughout Europe and to the US) indicates that Waldensian leaders wrestled with Gould over teacher placement and school management. Then, as now, finding and keeping teachers could pose a challenge. Yet the letters also suggest, as those between Gould and Marsh did, that the battle involved power dynamics. Who exactly was in charge of this fight for education in Italy?

Some might say that both Gould and the Waldensians triumphed—a win-win situation. Following her early death in 1875, Gould’s husband handed her work over to the Waldensians. Yet testimonies left in articles such as one published in L’Italia Evangelica (1881), or in her biography, A Life Worth Living (1879), by Leonard Woolsey Bacon, celebrate Gould’s mission and vision. Visitors to Florence may see Gould’s name on the wall of the Waldenisan guest house in the Oltrarno neighborhood. And an institution bearing her name—still helping children—remains in Florence today and under Waldensian direction.

*****

Want to know more about Emily Bliss Gould? She is one of the three women featured in Engaging Italy: American Women’s Utopian Visions and Transnational Networks (SUNY Press 2022). (You can get a 30% off sale coupon for the paperback edition, which will be released on October 1, on Etta’s website, ettamadden.com.

For more insights to American women writers abroad and, specifically, about Italy, subscribe to Etta’s monthly newsletter, All Things Italy through the website.

Want to schedule a talk? Feel free to reach out through email or social media: Ettammadden@gmail.com

You can follow Etta on Twitter and Instagram at @ettamadden

September 28, 2022

Road Trip Through History: Unexpected Stories in Quincy Illinois

Quincy, Illinois, was our final stop on this segment of driving the Great River Road.* It wasn’t so much a stop as a pause on our way home. But it was a good pause, with some unexpected stories.

The town has a number of museums and restored historical homes. It also has an interesting outdoor display about Lincoln’s visit to Quincy for his debate with Stephen Douglas: basically the city’s equivalent of an academic poster session.

It will probably not surprise you to learn that we spent most of our time at the local historical society, which is located in a restored historical home. Like many local historical museums, it had exhibits on the town’s founders,** its early residents, and some of its successful industries. (I addition to All of which is always interesting.

But two exhibits that were less typical caught my imagination:

One room was dedicated to the interactions between the residents of Quincy with Mormon refugees, first in the winter of 1838-1839 when they were driven out of Missouri and again in 1846, when they were forced to abandon their settlement in neighboring Nauvoo.*** I won’t try to condense the history of the Mormon exodus here. It is too complicated. And it wasn’t the focus of the exhibit, which detailed the efforts of a small town to provide food, shelter, medicine, and most important of all, compassion to strangers in need.

Another room focused on the history of Quincy’s Black residents. While many historical museums today are attempting to add women and people of color to their exhibits—an act I salute—it is quite clear that the Quincy museum’s exhibit predates that effort. Part of the room told Quincy’s role in the Underground Railroad but much of the room focused on individual Black citizens and their contributions as entrepreneurs, educators, abolitionists, and decorated war heroes.

Within that exhibit, one story stood out for me:

“Free Frank” McWorter and his wife Lucy founded New Philadelphia, the first town in the United States to be platted and registered by Black settlers.

McWorter was born a slave in South Carolina in 1777 and then was taken to Kentucky by his owners. There he met Lucy. He was allowed to hire out his time, which meant he could buy their freedom. He bought Lucy’s freedom first, in 1817, which meant any children they had after that date would be born free. He bought his own freedom in 1819, then that of his oldest son.

In 1830, the McWorters moved to the Illinois frontier, where they established a farm. (The same year Abraham Lincoln arrived.) In 1836 , they founded the town of New Philadelphia. The town was racially mixed from the beginning and its residents were active in helping escaped slaves go north. The McWorters also managed to purchase the freedom of at least sixteen more family members.

Like many other frontier towns of the period, New Philadelphia did not last, but it was never forgotten. By 1885, many villagers had moved away looking for new opportunities. By 1940, nothing remained, though descendants of the town’s residents lived in the area until the 1950s.

Today, the New Philadelphia site is the subject of ongoing archaeological explorations, which are uncovering information about daily life in free Black rural communities. There isn’t much to see now, but legislation is in process to make the site part of the National Park System.

*Some of you may be saying, “Finally!”

**Who took advantage of the equivalent of the G.I. Bill for veterans of the War of 1812, in which the government set aside 5.4 million acres in Western Illinois, between the Illinois and Missouri Rivers. Each veteran or his descendants was “entitled” to a warrant for a full quarter section (160 acres), which allowed him to claim land and receive title for it. (The exhibit did not point that Native Americans already lived there, so I will.)

***Which was our first stop, back in 2014, on what has become a multi-year Great River Road adventure. We’ve got at least one more stretch to do. Maybe two.

*****

Travelers’ Tips

Thyme Square Bakery and Cafe in Quincy is an excellent place for lunch. If we’d gotten there earlier, I would have bought a loaf of bread to take home, but the locals had beat me to it.

If you want to visit the New Philadelphia site, do NOT put New Philadelphia, Illinois in your GPS. It will take you to an existing town in the other direction. Trust me on this.