Pamela D. Toler's Blog, page 2

October 24, 2025

Boat Trip Through History: Muhammad Ali (No, Not the Boxer)

I recently got back from two weeks in Egypt with my BFF from graduate school: a river cruise on the Nile with many shore expeditions to see the things a card carrying history nerd would expect to see, and some things that were totally unexpected.[1] I have stories to share—probably more than I will actually manage to tell because it gets harder to channel the excitement with the passage of time. Let’s go!

***

Our first expedition was a visit a site known as Citadel Cairo, which includes the citadel built in the twelfth century by Saladin to protect Cairo from the Crusaders,[2] and a mosque built by Muhammad Ali Pasha in the mid-nineteenth century. I was looking forward to seeing Saladin’s citadel and learning more about him. Instead, the focus was the mosque and Muhammad Ali, an Albanian mercenary in the employ of the Ottoman Empire who became the defacto ruler of Egypt and is often described as the father of modern Egypt.[3]

I remembered a few disconnected stories about Muhammud Ali from my dissertation days.[4] (He fascinated European painters and poets during his reign.) But I didn’t have a feel for the bigger story. Once I got back home, I pulled my Big Fat Islamic History Books off the shelf and dove in.

Muhammad Ali Pasha, ca 1840, by Auguste Couder

The short version: It’s complicated.

The slightly longer version (which requires footnotes and asides because there is a lot of background information) :

Egypt was in political disarray when Muhammad Ali arrived in 1801. The three-year occupation of the country by the French under Napoleon had weakened the power of the Mamluks[5] who had ruled Egypt for more than 500 years, first as an independent sultanate and later as a provincial military and bureaucratic elite as part of the Ottoman empire. Determined to reassert their authority in Egypt, the Ottomans sent an occupying army, including a contingent of Albanian soldiers led by Muhammad Ali. As the Mamluks and the Ottomans duked it out for the control of Egypt, Muhammad Ali played each side against the other, slowly strengthening his position in Egypt at the expense of both.

In 1805, the sheikhs and ulema of Cairo led a revolt against the Ottoman viceroy. In the course of that revolt, the ulema declared Muhammad Ali governor of Egypt.[6] The Ottoman sultan confirmed the appointment several weeks later, perhaps with some hesitation given Muhaammad Ali’s track record of grabbing power whenever he got the chance.

Muhammad Ali was now the Sultan’s man in Cairo, but he still had to deal with the Mamluk forces. In 1811, after several years of political and military fighting with the Mamluks, he organized the death of the remaining Mamluk leadership, an atrocity known as the “Massacre at the Citadel”. He invited some 500 Mamluk rulers to a ceremony at the Cairo Citadel, which remained the military and political center of Egypt in the centuries after Saladin.[7] As they entered the citadel’s massive gateway the gates swung closed and the Mamluks were shot down. [8] The massacre of the leaders was followed by an indiscriminate slaughter of Mamluks throughout Egypt. (They were, after all well-trained, well-organized soldiers, with a history of promotion from within. They could well have risen up against him under new leaders..)

With the Mamluks out of the way, Muhammad Ali began to rebuild Egypt into a regional power, sometimes acting as the agent of the Ottoman empire and sometimes acting against them. He invaded the empire in 1831 and again in 1840—both times England and France intervened on the Ottomans’ behalf. In 1840, he accepted a brokered peace, withdrawing from Ottoman territory in exchange for hereditary rule over Egypt for himself and his sons. His dynasty ruled Egypt for more than a century, until the revolution of 1952, when King Farouk was deposed.

[1] As those of you who get my newsletter know, I was gobsmacked by the sheer size of Cairo.

[2] He used stones taken from some of the smaller temples at Giza—not the first ruler to reuse building materials from an earlier culture.

[3] Personally, I think that title should go to Gamal Abdul Nasser, the Egyptian military officer who was a leader in the revolution against King Farouk in 1952 and played a major role in creating the Republic of Egypt.

[4] See link to my newsletter above if for some unimaginable reasons you want to know more about the dissertation

[5] The Mamluks were not actually a dynasty in the way we normally use the word. They were a self-perpetuating military elite made up of freed slave solders. When one sultan died, his inner circle chose his successor from within their ranks. (Perhaps the Mamluks should be the subject of another blog post? Let me know if you’re interested.)

[6] The Ottoman viceroy did not go quietly, but this is still an abbreviated version of events. Assume lots of violence at every stage of the game.

[7] Why let a mammoth stone fortress on the high ground go to waste?

[8] This event captured the European imagination at the time and was the subject of a number of Orientalist paintings. most notably The Massacre of the Mamelukes by Horace Vernet. 1819

October 20, 2025

Isaac’s Storm: A Man, a Time, and the Deadliest Hurricane in History

For several months now, Isaac’s Storm: A Man, a Time, and the Deadliest Hurricane in History by Eric Larson has been my traveling book—the one I read on airplanes and city buses. I recently finished it on the last leg of a trip. And I have thoughts.

Isaac’s Storm tells the story of the hurricane that flattened Galveston in 1900. Larson captures the epic scale of the storm while telling us a human story of tragedy and loss.

Larson uses more than half the book to build to what he terms the cataclysm, a combination of unstoppable natural power and bad decisions based on hubris. He opens the book on the night before the storm, introducing us to Galveston and to Isaac Cline, the U.S. Weather Bureau’s resident meteorologist in Galveston. In the second chapter, he introduces us to the other major character of the book, the storm itself, with a breathtakingly beautiful line: “It began, as all things must, with an awakening of molecules.” Moving forward he describes how the storm grew, making the science of hurricanes clear to this non-scientist.[1]—and how new the science of meteorology was at the time. He gives us the history of the Weather Bureau, and a vivid picture of how political infighting within the organization contributed to multiple miscalculations about the power of the storm and where it would hit land. He introduces us to individuals in Galveston. He builds the tension.

The pace picks up when the storm hits Galveston. Using telegrams, newspaper accounts, letters, and later memories of Cline and others, Larson takes his readers back and forth through the city, tracing the experiences of the people to whom he has previously introduced us. Each story is marked with uncertainty, as people make decisions that will determine whether they and those around them will live or die. Larson’s storytelling is masterful in this section, holding the reader is suspense as he moves from vignette to vignette

Isaac’s Storm came out in 1999—not Larson’s first book but his first work of the narrative non-fiction for which he is famous. When compared to his later books of his, it is clear that he is still learning his craft. If I felt any disappointment, it is because I have read later work: early Larson is still better than many books that I read.

*****

A small coda: As those of you who have been following me around for a while know, I adore footnotes. For those of you who ignore the footnote section, Larson opens his notes in this book with a lovely brief essay on exploring “the lives of history’s little men.” I strongly recommend it to readers, and writers, of biography. I think I will return to it in the future.

[1] I will admit, several days after I closed the book, I would not be able to reproduce most of the science if you asked me to do so.

September 29, 2025

Gone Fishin’

I’m getting ready to go on a Boat Trip Through History with my BFF from graduate school. We’re taking a river cruise on the Nile where we will see all they things we dreamed of as nerdy little girls who were fascinated by ancient Egypt. Nine-year-old Pamela would have been over the moon. For that matter, middle-aged Pamela is pretty dang thrilled.

I have no doubt I’ll bring back stories to share.

Later, y’all.

September 25, 2025

Matisse at War: A Q & A with Christopher Gorham

Matisse at War: Art and Resistance in Nazi-Occupied France, by Christopher Gorham, is a vivid portrayal of the the advance of fascism and war into French life and culture during World War II, told through the lens of one of the country’s most celebrated post-impressionists and his family. How could I resist learning more? (Warning: I found myself pulling art books off the shelves as I read.)

Take it away, Christopher!

What path led you to the story of Matisse’s life in Nazi-occupied France? And why do you think it’s important to tell this story today?

Two things. One was a book I came across in the mid-‘90s, Artists Under Vichy. In it, the author accused Matisse of essentially sitting out the Second World War, living in relative comfort in Nice. That seemed inconceivable to me: not only was Matisse a modernist, a creator of so-called “degenerate art,” but his daughter had been in the Resistance, so I thought, how could this be? Second, my wife and I have had the good fortune to spend time in Nice, France each summer, visiting the Matisse landmarks. Was it really possible that Matisse simply painted his way through the war, ignoring the German occupiers and the Vichy collaborators? Or did he seize a patch of the cultural battlefield? Was he among the artists who were censored? How did his efforts affect his fellow citizens? These were the questions I wanted to answer.

Most of my readers will recognize the name Henri Matisse. Are there particular challenges in writing about a person people think they know something about?

I quite enjoyed it! My previous book was a biography of a once-famous presidential advisor, Anna Rosenberg, who was lost to history. It’s a lot easier to give your elevator pitch when it’s about a world-famous figure like Henri Matisse! What I found interesting about Matisse is that from his contemporaries until today, there is this notion that he was a painter of pretty things; a man who indulged himself in the pleasures of Nice; an artist untroubled by the events unfolding around him. First, Nice was the site of a four-way war between the Allies, Axis, right-wing militia, and French Resistance. Second, while it is true Matisse used vibrant color and flawless lines, much of his work during the Occupation held a latent menace, a sense of confinement, or being surveilled. His work reflected his angst over the war and over the fates of his family and friends. As his son Pierre told the New York Times in 1942, artists during wartime don’t paint skulls and battle scenes, they reflect, they filter, and sometimes it takes a keen eye to see their pain.

Did looking at this period of Matisse’s life give you a new/different understanding of his work?

Yes! I am not an art scholar. My wheelhouse is modern American history, the 1940s, the ‘50s, so this was a journey of discovery. Why did Matisse create so many cut-outs in his “second life”? Why did he use blue in so much of his work? Why did he make so many stylistic pivots? What was he in search of? I was able to answer many of these questions, but I still find it mysterious and awe-inspiring to see his art up close; it is so vibrant, so evergreen, so fresh, and so moving.

Writing about a historical figure like Henri Matisse requires living with him over a period of years. What was it like to have him as a constant companion?

Before setting off on his biography of Harry Truman, David McCullough had planned to write about Pablo Picasso. At some point, he got fed up. Picasso was a jerk, and McCullough didn’t want to spend years in his company. He moved on to Truman, and I think helped put Truman in the top ranks of modern American presidents. I was so fortunate to write the biography of Anna Rosenberg, who was smart, loyal, patriotic, witty, and respected by trucking unions and U.S. senators alike. I loved being in her company. She cherished American democracy, and worked to strengthen it by striving for greater social equality for women, for working people, for Black Americans, and for veterans. When I set off on Henri Matisse, I had a vague idea, but I found him to be an engaging figure, one who on the one hand could be economical with his thoughts—he spoke through the images he created–but who could also be a candid correspondent in his letters. While he did so in a very different way, Matisse, too, cherished the republican values of liberty, equality, and fraternity.

Historians of the resistance in Nazi-occupied countries often draw a contrast between active and passive resistance—a distinction that I feel is often artificial and discounts the very real danger of those involved in “passive” resistance. Where would you put Matisse and members of his family on the active/passive continuum? Or do you reject the distinction entirely?

I don’t love the word passive, but I think it’s fair to say that compared to his daughter Marguerite, who was a courier for a Resistance network, and his son Jean, who assisted British Intelligence in the South and who harbored Allied agents, Henri Matisse was engaged in a form of resistance that suited his stature, his advanced age and his failing health. Matisse didn’t need to be a bomb-thrower; by defiantly remaining in France and by steadfastly continuing to create subtly patriotic work, he resisted and gave succor to the Resistance. Each member of the Matisse family was playing for real stakes. As Françoise Gilot said, by holding his work up against the destructive impulses of the Nazis and their collaborators, Matisse was a beacon of hope for the young. Louis Aragon, the “Poet of the Resistance” who befriended Matisse during these years, wrote quite powerfully that “Matisse was of France, Matisse was France.”

What was the most surprising thing you learned working on this book?

There were many surprises. Perhaps the most dramatic one was a remark by Matisse to one of Varian Fry’s assistants (Fry was an American sent to Marseille to rescue artists from Nazi Europe). Matisse said, basically, that he’d provided a safehouse for enemies of the regime. The risks that his family took were also very sobering. Certainly his daughter, Marguerite, and probably his son Jean, were lucky to make it out of the Occupation alive. And the tension between Matisse’s bourgeois, middle-class grounding and his daring and audacious artistic flights is a source of awe for me.

Is there anything else you wish I had asked you about?

This is a book about art and war, and I hope to have also illuminated the role Nice played. From 1940 to late 1942, Matisse’s adopted city was under Italian jurisdiction—neither occupied by Germans, nor under the curdled regime of Vichy–a haven of relative normality in Hitler’s Europe, where Jews lived and worked without the yellow star. In the second half of the war the Mediterranean port became the locus for battles between pro-Nazi militia and Resistance fighters; Nazis and the Jews they hunted; and finally Germans and the American liberators. Henri Matisse had traveled to the United States and liked much about it. Perhaps his wartime cut-out The Cowboy was an homage to the American soldiers and the country that had liberated France twice in Matisse’s lifetime.

Art credit: Joshua Pickering

Christopher C. Gorham is a lawyer, educator, and acclaimed author whose books include Matisse at War and the Goodreads Choice Award finalist, The Confidante. He is a frequent speaker at conferences, literary events, colleges, and book club gatherings. He lives in Boston, and can be found at ChristopherCGorham.com and on social media as @christophercgorham.

September 22, 2025

Sisters of Influence: A Q & A with Andrea Friederici Ross

I am happy to have Andrea Friederici Ross back here on the Margins to discuss her latest book about forgotten women changing in the world. Sisters of Influence: A Biography of Zina, Amy, and Rose Fay tells the story of three extraordinary sisters who defied the expectations of their Victorian-era childhood and left their mark on history.

Take it away, Andrea!

Even well-known women in the nineteenth-century are often neglected by biographers and historians. What path led you to the Fay sisters, and why do you think it’s important to tell their stories today?

I’ve done some work in animal rescue, so the first sister to come to my attention was Rose, who founded the Anti-Cruelty Society in Chicago. That she was married to Theodore Thomas, the first conductor of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra, just added to my interest. Gradually I became aware that she had these remarkable sisters, so I had to incorporate their stories as well. What I thought would be a fairly simple story became very involved once I decided to include Zina and Amy. In addition to learning about the humane movement and the classical music scene in the States, I had to educate myself on cooperative housekeeping, women in music, higher education for women, and other issues the sisters tackled. But, in the end, it makes for a better story — one that incorporates many different things women were championing in the late 1800s. The Fay sisters were a kind of real-life Little Women. They each utilized their unique skills, voices, and personalities to move their issues forward. I think this is so pertinent today: by following our passions to enact change, gradually, society evolves in a more positive direction. There is no place for stagnancy, no time for apathy. Every voice matters.

Zina, Amy, and Rose Fay were all trailblazers in their separate fields during the Progressive Era, a period marked by many political and social reform movements. What new challenges and opportunities did women face at that time, and how did they affect the Fay sisters directly?

The Fay sisters grew up in the Victorian Era, at a time when women were expected to confine themselves to the domestic realm. But through their work in women’s clubs, their writings (all three were authors), and their organizational efforts, they — along with many, many other women — helped expand the women’s sphere into the community and beyond. The Fay sisters were, in effect, bridges from the Victoria Era into the Progressive Era. It begs the question: what about us? What important historical periods are we bridging, as women? Which direction do we want to head?

Writing about historical figures like the Fay sisters requires living with them over a period of years. What was it like to have them as your constant companions?

Ha! They were good company, actually. I have three amaryllis plants that I named Amy, Zina, and Rose, and I kept them abreast of the progress on the manuscript. They say talking to plants helps them grow? I felt like it was the converse — they helped keep me on track.

Did the Fay sisters cross paths with the subject of your last biography, socialite-activist Edith Rockefeller McCormick?

Yes! In fact, they lived on the same street! I was able to figure out several instances where some of the sisters and Edith intersected. That said, they were very different personalities! For example, Edith cherished a fur wrap made of chinchilla skins. Rose, describing what may well have been that very coat, wrote, “A thousand painful deaths in one garment!”

I realize this is an unfair question, but did you have a favorite among the sisters?

As you surely suspect, I did. I started out primarily focused on Rose but, in the end, Amy’s winsome personality won me over. I think, of the three sisters, Amy is the one I’d choose as a friend. Zina was a difficult personality and, while I respect what she was trying to accomplish in terms of restructuring housekeeping to make women’s lives easier, I took issue with some of her exclusionary attitudes. And Rose was lovely but I think I’d share more laughs with Amy.

How difficult was it to find sources for these women?

I got lucky this time! Usually this is one of the most challenging parts of writing about women. But, thanks to work done by Sylvia Wright Mitarachi, a Fay descendant and writer, all of the sisters’ papers are at Schlesinger Library in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Mitarachi obtained a grant to write a biography about Zina but died before finishing the project. I was able to benefit from the materials she had gathered and organized. She even transcribed some of the cross-hatched writing in the family letters — bless her heart! We stand on the shoulders of those before us, right? I think of this quote every election day and it rang true throughout this project as well, particularly with regard to Sylvia Wright Mitarachi.

What was the most surprising thing you learned working on this book?

It’s important to note that the Fay sisters were not among the early suffragists. They weren’t fighting for the vote — they were advocating for greater involvement in their communities and the issues they cared about. This is an area of women’s history that I never learned about! The women’s movement was far more nuanced than just pro- or anti-suffrage. Much as I would have preferred for them to be among the early firebrands who paved the way for us to vote, the Fay sisters gave me a far deeper understanding of the decisions women had before them at that time. While gaining the vote was a monumental step, the quieter, gentler approaches many other women took also helped expand the possibilities for all of us today. Quiet and gentle can also be effective.

Andrea Friederici Ross is the author of Sisters of Influence: A Biography of Zina, Amy, and Rose Fay, as well as Edith: The Rogue Rockefeller McCormick, and Let the Lions Roar! The Evolution of Brookfield Zoo. She has worked as the operations manager of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra, as assistant to the director of Brookfield Zoo, and at her local public school library. She enjoys speaking about the women in her books and has teamed up with historical interpreter ElliePresents to offer unique author programs bringing the women to life.

_______

Sisters of Influence will be released on October 14. It is available for pre-order wherever you buy your books.

September 18, 2025

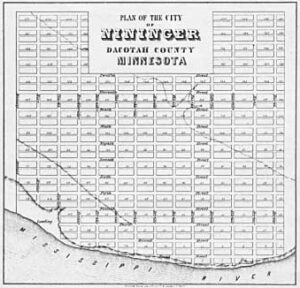

Road Trip Through History: The Boom and Bust of Nininger, Minnesota

To my surprise, ghost towns were a recurring theme of our multi-year trips along the Great River Road. More than once we saw small exhibits dedicated to towns that had grown up to support the fur trade, the logging industry, or mining and withered away because industries closed, transportation routes changed, or county seats shifted. A chilling reminder of the impermanence of the things we build.

On our most recent trip, in and around the Twin Cities, we were introduced to a new type of lost town, courtesy of a historical marker. Founded in 1856 on the banks of the Mississippi, Nininger Minnesota did not grow organically around an industry. The town’s founders, John Nininger, and Ignatius Donnelly moved to Minnesota with the plan of building a new city as a contender for Minnesota’s capital. It was not an implausible goal at a time when Minnesota’s cities were just taking shape.

In order to create the appearance of a boom town, Donnelly purchased 100 of the 3,800 platted lots and advertised the benefits of the new community in newspapers and immigrant neighborhoods throughout the Eastern United States.

By 1857, the new town, with seventy buildings and a population of some 1,000, was a bustling river port.[1] It had everything you would expect in a river port at a time when lumber was booming: two sawmills, a grist mill, several factories, two boarding houses, six saloons, and a dance hall, not to mention a baseball team. The developers had aspirations to be more than just a successful port. They had plans for a public library, a debate hall, and an athenaeum–which in my mind is a combination of a public library and a debate hall, but I am not an urban developer with big dreams.

Those dreams crumbled in the Panic of 1857.[2] By 1869, Nininger City existed largely on paper, though Donnelly’s two-story mansion remained, overlooking the failed city from a hill on river. By 1932, there was nothing left except Donnelly’s mansion and the foundations of a few old buildings, hidden in the prairie grass.

Donnelly lived in his mansion until his death in 1901: one of those larger-than-life enthusiasts (aka eccentrics) whom the nineteenth century produced with some regularity. After Minnesota became a state in 1858, he served three terms as a congressman and one as its lieutenant-governor. He wrote the best-selling Atlantis: The Antediluvian World (1882)[3] , which is credited with popularizing the idea of the lost civilization, and three books arguing that Francis Bacon wrote not only Shakespeare’s plays, but the works of Marlowe and Montaigne. He supported women’s suffrage and the Farmers’ Alliance, an agrarian movement which sought to improve economic conditions for farmers through political advocacy and the creation of cooperatives. He ran for vice-president on the tickets of two different populist parties. (Not at the same time.)

[1] By comparison, St. Paul, the capital, had a population of roughly 10,000. The population of Minnesota as a whole was about 85,000.

[2] Here’s the short version:

Grain prices dropped due to a combination of bumper crops and reduced demand from Europe due to the end of the Crimean War. Foreign trade imbalances led to a drain on the nation’s gold reserves and increased interest rates. Banks failed. The development of railroad had been a driver of the economic boom that preceded the panic. Now the collapse of credit halted their construction. Unemployment in the large cities of the Northeast and the Midwest soared.

The Panic of 1857 also widened the economic differences between the North and the South, The South, which was less industrialized than the North, did not suffer to the same extent. Low tariffs (ahem) protected its cotton trade with Europe, and sustained its overall economy.

[3] Still in print 140 years later. I can only dream.

September 15, 2025

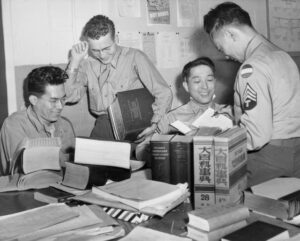

Learning Japanese at Fort Snelling during World War II

One of the first things we saw when we got to Fort Snelling was a row of storyboards posted along the sidewalk leading to the visitors’ center. One of them showed a photo of three young Asian-American women in uniform, with a quotation above them:

“I was born in the states, in Nebraska, and I’m an American just like you.”

Sue Ogato Kato. Women’s Army Auxiliary Corps, U.S. Army 1943-46.

As I read further, I learned that Sue Kato translated Japanese documents for the American army. I was eager to learn more. Fort Snelling did not disappoint.

In addition to serving as an induction center for new recruits during World War II, Fort Snelling was home to the Military Intelligence Service Language School (MISLS), where second generation Japanese (Nisei) like Sue Kato were trained to read and speak Japanese to prepare them for work as interpreters, interrogators, and in some cases as spies.

Shortly before the war began, the American military recognized they would need Japanese linguists. The military, sharing the general prejudices of the time, would have preferred linguists who were fluent in Japanese but were not themselves Japanese. It turned out to be a very small population. Their next choice were second generation Japanese immigrants, the Nisei, who proved to be less fluent in Japanese and more American culturally than the military leaders had expected. (Only three percent of the Nisei already in the army spoke fluent Japanese,) Even those who spoke Japanese well were not familiar with military terminology in that language or details of the Japanese army.

A month before Pearl Harbor, the Army opened a small class of 60 language students in an empty airplane hangar on Crissy Field at the Presidio in San Francisco. The first class graduated in may, 1942, the same month that the American government began to move Japanese-Americans into internment/concentration camps. With California, western Washington and Oregon and southern Arizona designated as an Exclusion Zone from which Japanese were barred—and overt hostility in California for Asians, even those in military uniform—the school needed to be moved away from the West Coast. MISLS moved to Minnesota, first to Camp Savage and then, as the number of students grew, to Fort Snelling.

More than 6,000 linguists graduated from MISLS, including many recruited from the camps. The curriculum was intensive. In addition to becoming both fluent and literate in Japanese, students learned Japanese army jargon. They learned to read a special style of Japanese used in personal correspondence. They studied captured documents and Japan’s history and culture. They learned to read maps and monitor radios. In 1945, the school added courses in Chinese and Korean and civilian administration in anticipation of new challenges after the end of the war.

Once in the field, MISLS graduates translated and interpreted documents, interrogated prisoners, and communicated with civilians. They convinced soldiers and civilians to surrender at Iwo Jima and Okinawa. One of their most important contributions was translating the “Z Plan,” captured documents which outlined Japanese plans to counter attack in the Southwest Pacific in 1944. General MacArthur’s chief of military intelligence, Major General Charles Willoughby, later claimed The Nisei shortened the Pacific War by two years and saved possibly a million American lives and saved probably billions of dollars.”

Their work continued after the war. MISLS graduates served with the army of occupation in Japan and during the Pacific war crimes trials, where they monitored the work of Japanese translators for accuracy.

In 1946, the school moved to Monterey and was renamed the U.S. Army Language School

September 12, 2025

From the Archives: Curiosity’s Cats

By the time this post is available for you to read, I will be deep in the final day of a four-day exploration of a previously untouched and barely organized archive. I hope to come out the other end knowing whether I have enough material to write a proposal about a subject I’m interested in. (And no, I’m still not giving you any hints.). I had hoped to have a new blog post for you today, but it’s only halfway done and I’m running short on time and brain power. Instead I’d like to share a post about doing research from 2014.

Wish me luck!

Research is a big part of my writing work day. In fact, I read far more words than I write in my constant search for a topic, a story,* and/or a telling detail. I have special glasses for the hours I spend on the computer, and eye drops that I generally forget to use. (Excuse me, while I pause and lubricate.)

More importantly, I have library cards for five local library systems, am an active user of Interlibrary Loan, and frequently max out my borrowing privileges. Because contrary to popular opinion, you really can’t find everything on the internet.** Sometimes you need to browse the shelves, skim an index, read a primary source or an authoritative history, succumb to the allure of the archives, or ask a reference librarian for help. Some of the most satisfying moments of my career have occurred in libraries.***

Bruce Joshua Miller, editor of Curiosity’s Cats: Writers on Research, makes no secret of his discomfort with researchers’ increasing dependence on digitized sources. The 13 essays he commissioned for the collection share a common mandate: tell a story about a research project that required techniques beyond computer searches. The resulting collection could have been an extended Luddite shudder against technology or a simple exercise in nostalgia. It is neither, though several of the essays include a variation on “I’m not a Luddite, but…” and the final essay (Marilyn Stasio’s “Your Research–or Your Life!”) uses nostalgia to pointed effect. Instead, each piece explores the complicated and often personal relationship between writers and their research.

The essays, written by novelists, historians, journalists and a filmmaker, vary widely in topic, tone and method. Some give detailed accounts of methodology, like historian of science Alberto Martínez who gives a step-by-step account of the convoluted and creative process tracking down a single elusive fact: the date that Albert Einstein had the intuitive flash that led to the theory of relativity. Others, like essayist Ned Stuckey-French, who describes research as a way of life for his entire family, are more impressionistic. Despite the book’s focus on non-digital discoveries, several also celebrate new opportunities of on-line digging.

Whether funny or poignant, describing the insights that come from getting lost in a strange city or the development of a research path over the course of a career, the essays in Curiosity’s Cats celebrate the joy of research on-line and off.

* Topic and story are not the same. This is the first lesson any writer must learn if she wants to survive.

**Though you can find more than you may realize if you know how to look. I take a lot of pride in my on-line search skills.

***Not to mention some of the most embarrassing. If you meet me in person ask me about the “sexist man alive” incident at Chicago’s Harold Washington Library. Let’s just say librarians don’t always whisper.

September 8, 2025

Fearless: A Q & A with Cathy Curtis

I am delighted to have biographer Cathy Curtis back on the Margins to discuss her new book, Fearless, the first comprehensive biography of Irish writer Edna O’Brien (1930-2024). Pull up a chair and enjoy the conversation!

What drew you to Edna O’Brien’s story?

I had been a longtime fan of Edna O’Brien’s novels and short stories, always keen to buy her latest book. While I was in the final stages of my previous book, I looked for another contemporary writer whose work I admired, who had not yet been the subject of a comprehensive biography, and who had led an eventful life.

Writing about a figure like Edna O’Brien requires living with her over a period of years. What was it like to have her as a constant companion?

Delightful! She was a mercurial person, quick to take offense, but her other traits were endearing to me: her passion for ultra-feminine clothes; her impulsive generosity; her abiding love for her two sons; her passionate romances with men unable to cope with her intensity; her wry sense of humor; her ability to use her intimate experiences as the basis of memorable fiction; her unwavering belief in the power of the written word; and above all, her extraordinary perseverance in the face of personal tribulations and literary snubs.

Are there any special challenges to writing about a woman who was a literary superstar in the second half of the twentieth century?

All five of my biographies are about notable women whose careers blossomed during the second half of the twentieth century, the historical period in which I feel most at home. But my previous books were about Americans. The challenge with this biography was to learn more about Ireland’s tragic history in order to comprehend the values and constraints that molded Edna’s way of looking at the world.

It was important to know that the Great Famine of the mid-nineteenth century had decimated the population, that Ireland’s fight for independence from the U.K. took agonizing decades to (partly) achieve, and that living under the total dominance of the Catholic Church had a terrible effect on human lives. I rewrote each chapter dozens of times, letting it “breathe” for weeks and returning to add more information, or to clarify what I had written.

Edna O’Brien died in 2024. Did her death change the book in any way?

She was in her late eighties and in declining health when I began researching the book in 2019, so her death was always on the horizon as I wrote. Afterward, I was able to write about her deeply moving funeral Mass (which I watched in real time on Vimeo) and to incorporate quotes from some of the people who wrote about their memories of her in the Irish and British press.

What was the most surprising thing you learned?

I had no idea how long it had taken for Edna’s work to receive serious recognition in the form of awards and reviews that did not belittle her writing as too overblown, too involved with women’s dashed romantic hopes, or “too Irish” to be the equal of works by prominent British writers. During her last years she finally received a bouquet of major awards, including the PEN/Nabokov Award for Achievement in International Literature, the David Cohen Prize for Literature, and the Prix Femina Spécial—all for her entire body of work. But her novels were never even shortlisted for the Booker Prize, the most famous British literary award.

Did the writing of this book lead you to make other discoveries?

Yes, I began reading the seemingly endless stream of brilliant novels by younger Irish authors. The last chapter of my book takes a final look at Edna O’Brien’s life and work alongside brief mentions of remarkable novels by ten contemporary Irish women authors who in some way owe their candor and literary inventiveness to her writing.

Cathy Curtis is the author of four previous biographies of prominent 20th-century women in the fields of visual arts and literature: Grace Hartigan, Elaine de Kooning, Nell Blaine, and Elizabeth Hardwick. Fearless: A Biography of Edna O’Brien will be published on September 9, 2025. Curtis is a former journalist, a member of The Authors Guild, and a past president of Biographers International Organization. Her website is www.cathycurtis.net

September 4, 2025

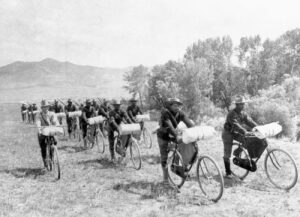

Buffalo Soldiers on Bicycles

This is one of my favorite stories from our visit to Fort Snelling:

After the American Civil War, Congress created six regiments of Black soldiers, led for the most part by white officers, known informally as Buffalo Soldiers.[1] One of those regiments , the 25th Black Infantry, was posted at Fort Snelling in 1880. Eight years later they were transferred to Fort Missoula, Montana, where this story took place.

****

At the end of the nineteenth century, bicycles were all the rage. The bicycle was as popular with members of the army as it was with the general public. In 1894, roughly half the personnel at Fort Missoula had bicycles and the fort was holding informal bicycle drills, which included members of the 25th Infantry.

In 1896, Lieutenant James Moss, commander of the 25th Infantry Regiment in Missoula,[2] took the idea one step further and proposed that the military could replace horses with bicycles for some operations.[3] Bicycles, unlike horses, did not need food water or rest. They were virtually noiseless. He was not the first Army officer to suggest the use of bicycles by the military. Several years previously, then Major General Nelson A. Miles tested the possibility of using bicycle couriers. (Among other things, he reported, his bicycle trials demonstrated the wretched condition of American roads.)

Moss’s request to organize an experiment with bicycles was approved on May 12, 1896. A little over a year later, after months of training that included daily rides of fifteen to forty miles and two longer excursions to Lake McDonald and Yosemite during which they carried rifles, rations, and equipment, the 25th Infantry Regiment Bicycle Corps, also known as the Iron Riders were ready for a much longer expedition. This ride was designed to demonstrate to the Army leadership that bicycles would be an efficient way to transport soldiers in time of war. Moss described the corps as “bubbling over with enthusiasm . . . about as fine a looking and well-disciplined a lot as could be found anywhere in the United States Army.”

On June 14, 1897, twenty soldiers, two officers and one reporter set out on a 1,900 mile bike ride from Fort Missoula to Saint Louis. The route took them through a variety of terrain and climates. Averaging 50 miles a day for 41 days, on bikes specially made for them by Spaulding Bicycle Company, they rode on unpaved roads and occasionally on railroad tracks. (Not a fun surface to ride on, as anyone who ever rode a bicycle can imagine.) They crossed mountains and forded rivers. They rode through snow, sleet, rain, and oppressive heat. Sometimes the ground was so muddy and slippery that they had to push their bikes for several miles.

By the time the riders reached Missouri, the story had caught the public imagination. When the members of the 25th Infantry Regiment Bicycle Corps reached St. Louis on July 24, almost 1000 local cyclists rode out to meet them. Crowds lined the streets to greet them as they rode into the city, In the following days, tens of thousands St. Lois residents visited the corps’ camp in Forrest Park and watched them perform exhibition drills.

The discovery of gold in Alaska replaced the story of the bicycling Buffalo Soldiers in the nation’s headlines. The corps was disbanded once it reached Missoula, traveling this time by train. Lieutenant Moss remained optimistic about the value of the bicycle to the military in his report to the War Department and requested permission to organize a second bicycle corp. But with the outbreak of the Spanish-American War, the military moved further experiments with bicycles to a back shelf.

The 25th Infantry Regiment left Fort Missoula for training camps in Georgia and Florid. From there, the unit saw action in Cuba and distinguished itself in the Spanish-American War. Moss returned from Cuba and proposed a company of 100 soldiers on bicycles to patrol Havana once it was under the occupation of American troops. His proposal was rejected.

By World War I, the Model-T had replaced the bicycle as the hot new mode of transportation in the eyes of both the public and the military.

[1] By some accounts, the Native Americans against whom they fought gave them the nickname because their curly hair resembled buffalo manes and because of their fierce nature. Maybe. Maybe not.

[2] Racism was rampant in the army at the time. Moss graduated last in his class at West Point and had no choice in where he was assigned. As he later said in a speech in his home town in Louisiana “ Being a Southern boy I did not at first, I must admit, like the idea of serving with colored troops.” With time, he changed his mind and was proud to have them under his command.

[3] This was not as revolutionary an idea as is sometimes claimed. Italy created a military bicycle unit, which was used for reconnaissance and courier services, as early as 1875. Other European countries followed Italy’s lead. By 1890, France, Austria, Switzerland and Germany all had bicycle units.