Pamela D. Toler's Blog, page 9

March 12, 2025

Talking About Women’s History: Three Questions and an Answer with Shannon Frystak

Shannon Frystak, Ph.D. is a first-generation college student who went on to pursue a Masters and Ph.D. focusing predominantly on Women’s History. An award-winning writer and historian, she is Professor and Graduate Coordinator of the Department of History and Geography at East Stroudsburg University of Pennsylvania where she has taught since 2007. Her first book, Our Minds on Freedom: Women and the Struggle for Black Equality in Louisiana, 1924-1967 looked at the important and, often, overlooked work of female civil rights activists in a Deep South state. Her second book, Louisiana Women: Their Lives and Times, part of the Southern Women Series at the University of Georgia Press, is a collection of essays co-edited with her friend, Mary Farmer-Kaiser. She is widely published in a number of collections and journals and is currently working on a book about Lucille Watson, a plantation owner in Tensas Parish, Louisiana.

Take it away, Shannon

When did you first become interested in women’s history? What sparked that interest?

I always knew that I wanted to be an academic, in some capacity, but as I had worked full-time to put myself through undergraduate school at Bowling Green State University, my grades were less than stellar and I decided to take some time off before deciding on a career long-term. After traveling across country, living in Washington, D.C. and working as a waitress while I volunteered at the Community for Creative Non-Violence, a homeless shelter/advocacy program, I moved to New Orleans and it was here that I began researching programs that might interest me; it felt like there were so many possibilities. One day I was perusing the Peterson’s Guide to Graduate Programs and happened to notice that Sarah Lawrence had a Master’s program in Women’s History. One of my favorite classes as an undergraduate student was my Women’s Studies course and I had long been an activist, attending many a women’s march in our nation’s capitol. So, I gave it a shot and I applied. And I got in! However, being that my undergraduate GPA wasn’t up to par, mainly because I worked full-time as a bartender to finish school, they asked me to take a few classes at a local university to prove that I was up for the challenge of a rigorous graduate program. The class I chose was called “Black Movements and Messiahs,” and it was taught by professor and civil rights activist, Raphael Cassimere. That class everything changed – I began to do research into black women’s history, reading Nikki Giovanni and Paula Giddings, and this course led me to pursue a Master’s in what was essentially African-American Women’s History. My thesis looked at the integration of the New Orleans chapter of the League of Women Voters, a story I happened upon when researching the white activist, Rosa Freeman Keller. The local chapter of the League of Women Voters allowed me access to their records where I came across a thin folder titled “Integration.” That serendipitous find led me to expand my research and to what ultimately became my larger work on women in New Orleans and across the state who were an integral, yet overlooked, part of the Louisiana civil rights movement.

What unsung woman activist from the past would you most like to read a biography of and why?

I’m currently looking at the life of Lucille Watson, a white female plantation owner, who successfully oversaw the daily operations of her family’s cotton (and later cattle) farm in Tensas Parish, Louisiana, just over the Mississippi River from Natchez. Her life should be made into a movie – she was a young debutante who married her uncle when her aunt died, a tennis pro, an avid hunter and fisherwoman, an amazing host who loved to entertain and who’s Christmas Eve parties were notorious, and the chatelaine of Cross Keys plantation, until her death in 1985.

What work of women’s history have you read lately that you loved? (Or for that matter, what work of women’s history have you loved in any format?)

When I first began research in women’s history there was so little about women in Louisiana and writ large. Today there are so many wonderful histories and books dedicated to uncovering stories about women and their contributions to American history. Some of the best recently published include my good friend Virginia Summey’s work on Elreta Melton Alexander Ralston, the groundbreaking attorney and first black female graduate of Columbia Law School, who in 1947 became the first black woman to practice law in North Carolina. My friend Jess Armstrong, who has a Master’s Degree in History, has recently published some really fun and engrossing historical fiction – The Curse of Penryth Hall and The Secret of the Three Fates – set in early 20th century gothic Great Britain where the protagonist, Ruby Vaughn, solves mysteries in London, Scotland, and, next up, Oxford. The field of women’s history has expanded greatly since the 1970s and the studies of women in this country and abroad are numerous, illustrating how significant women are to the history of world.

A question from Shannon: What is something that you learned in your research/studies of women in history that was striking, something we wouldn’t otherwise know, that surprised you or delighted you? Something that was completely unexpected.

I will never forget learning that Alexander the Great had an older half-sister, Cynane, who was also a successful general—a story that scholars of the period are familiar with, but not one that makes it into mainstream world history classes. When I first stumbled across her story I literally ran down the stairs, shouting to my husband “You’ll never guess what I found!”

***

Want to known more about Shannon and her work? Check out her faculty page.

***

Tomorrow will be business as usual here on the Margins with a blog post from me. Then we’ll be back on Monday with six questions and two answers from Kim Barton and Johanna Wittenberg, novelists and hosts of the podcast “Shieldmaidens: Women of the Norse World.”

March 11, 2025

Talking About Women’s History: Three Questions and an Answer with Joan Fernandez

Former senior marketing executive, speaker, blogger and book reviewer, Joan Fernandez brings to light brilliant women’s courageous deeds in history. Her short story, “A Parisian Daughter,” is published in the award-winning anthology, Feisty Deeds: Historical Fictions of Daring Women. Her debut novel, Saving Vincent, A Novel of Jo van Gogh, will be published in April 2025 by She Writes Press.

Take it away, Joan!

What path led you to Jo van Gogh? And why do you think it is important to tell her story today?

I found out about Jo on a long weekend in Amsterdam. I was with three girlfriends, and we’d carved out a getaway between crammed schedules of kids’ sports and dual parental juggling and hectic work demands. It felt giddy, like we were getting away with some crazy caper, and gloriously indulgent since traveling with friends feels different than traveling with a spouse, when a big chunk of attention includes the other person’s welfare.

So, one of our stops is the Van Gogh Museum. I purchase the audio tour and immerse myself in Vincent van Gogh’s artistic tragic life as I follow the recording from painting to painting. In fact, it’s so engrossing that at the end of the tour there are tears in my eyes. At this moment I’m in front of the final exhibition boards. I notice a small notation about Jo—Vincent’s sister-in-law—and how she was the one who worked for over a decade to promote him. I remember staring at her photo and thinking, “If not for you, none of this would be here.” Like a fishhook, Jo caught my thought. A few years later I retired from my corporate career and decided to write her story.

Even though this year, 2025, will be the hundredth-year anniversary of Jo’s death in 1925, I believe her story is coming out at a crucially relevant time. There’s been a gathering storm of societal pressure against women’s rights and agency, Recent attacks on DEI initiatives is just one example. The fact that Jo prevailed despite her experiences of patriarchal prejudice can give comfort and inspiration to readers today. I think there’s a special impact from reading real women’s stories from the past that can give hope today.

How did you walk the line between historical fact and fiction in Saving Vincent?

I started with research from official biographies and letters, including reading the 101-letter exchange between Jo and Theo and all 902 letters of Vincent van Gogh’s correspondence. The first letter exchange gave me a sense of their relationship and what Jo valued and was curious about. I read Vincent’s correspondence because Jo read and organized Vincent’s letters after his death, getting to know him through his writing since she only met him three times in person.

At this juncture, I applied a storytelling framework: choosing an inciting incident, finding a point of no return, identifying a climactic moment, etc. Then I scoured my factual research to give intentional meaning to Jo’s moments within events, a timeline, art exhibitions and relationships. Overlaying all of it, I wanted to show her personal growth from a timid widow to the strong advocate she became. Finally, I also wanted to include societal pressures of her time, so I personified this headwind by creating a fictional antagonist, who represented pushback against her efforts from the art establishment.

How did your previous career as a marketing executive inform your response to Jo van Gogh, whom you’ve described as the “greatest marketer of the century?”

When reading Jo’s biography, my background in marketing caused Jo’s marketing strategies to leap off the page. I’ve gone back to identify eight specific strategies, many ahead of her time. For example, she was vigilant about protecting Vincent’s “brand”—responding to criticism even though it caused others to scold her publicly. Another tactic: she educated the public about Vincent by publishing excerpts from his letters and drawings in six editions of a prominent Parisian newspaper. These letters created curiosity around Vincent, which in marketing is creating awareness. She reminded me of a genius whose talent is so instinctive that what’s elusive to others feels perfectly natural. This genius transformed a product worth nothing (Vincent’s works) into one worth millions upon millions today. It’s by this measure that I’ve enjoyed calling Jo, the greatest marketer of the century.

A question from Joan: Over the long arc of humankind, you’ve studied and written about there have been shifting worldviews on women—what’s your perspective on the current rhetoric and backlash against women’s rights and agency?

First: I want to know if you people got together this year and said “Let’s ask Pamela hard questions.”

Okay, now that I’ve gotten that off of my chest, let me take a stab at this.

Speaking as a historian: progress is not a continuous upward curve. (The most dramatic version of this in American history is the backlash against the Reconstruction following the Civil War.) Instead, progress comes in fits and starts, whether we are talking civil rights, labor safety or clean air. Certainly in the case of women’s rights and agency, every step forward we have made has been followed by an attempt to push us back that was successful in the short run. (As I have said in previous posts I’m talking about the history of women’s rights because that is what I know best, but it is true of every marginalized group who has fought for equal rights.)

Moreover, progress does not occur evenly across a population. The 19th Amendment gave American women the right to vote, but did not address the rules that were already in place to disenfranchise Black men, and consequently Black women.* There is a reason that intersectionality—the way different forms of inequality overlap and exacerbate each other— is an important part of the discussion.

Just because this isn’t the first backlash we’ve seen against civil rights of the marginalized, doesn’t mean we can just wait for the pendulum to swing again. Advances are made because people fight for equality.

On a personal level, I am really angry and my stomach hurts all the time.

*The role of Black women in the suffrage movement and the racism of many of the leading White suffragists is too big a topic for me to handle here, and painful. I was shocked when I first learned some of the stories. I’ve said it before, and I suspect I will say it many times this year: history is hard, and perhaps it should be.

***

Want to know more about Joan and her work?

Check out her website at https://www.joanfernandezauthor.com

Read her provocative weekly essays as https://joanfernandez.substack.com

***

Come back tomorrow for three questions and an answer with Dr. Shannon Frystak, who studies the lives of historical women in the Deep sosuth.

March 10, 2025

Talking About Women’s History: Three Questions and an Answer with Margot Mifflin

Margot Mifflin is an author and journalist who writes about women’s history and the arts. She pioneered the study of women’s tattoo history with Bodies of Subversion: A Secret History of Women and Tattoo. Her second book, The Blue Tattoo: The Life of Olive Oatman, was a finalist for the Caroline Bancroft History Prize. Her most recent book, Looking For Miss America: A Pageant’s 100-Year Quest to Define Womanhood, is the first cultural history of the Miss America pageant. Margot’s writing has appeared in The New York Times, The NewYorker.com, Vogue, Vice, Elle, ARTnews, Bookforum, The Los Angeles Review of Books, The Believer, O, The Oprah Magazine, The Chronicle of Higher Education, The Washington Post, Feministing, Lapham’s Quarterly, Lit Hub, and other publications.

Margot is an English professor at Lehman College/CUNY and teaches arts journalism at CUNY’s Craig Newmark Graduate School of Journalism. She has served as a consultant on exhibitions at The Museum of Modern Art, The New York Historical Society, and The Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County, and curated the exhibition “Body Electric” at Ricco/Maresca Gallery.

Take it away, Margot!

Why do you think the Miss America story is important today?

We’re in the midst of a painful national reckoning about what it means to be American, and for the past century, the pageant has tried to define that by crowning an ideal American woman. The pageant’s trajectory reflects American assumptions about immigration (it was launched shortly after 20 million immigrants landed on our shores), national purity (for the pageant’s first 50 years, no women of color were crowned) and proper American womanhood (the swimsuit had just replaced woolen dresses women previously swam in, but the question of how much skin it could reveal was being literally legislated city by city.) It’s no coincidence that the pageant was launched a year after the 19th Amendment was passed; it championed values in direct conflict with the goals of first wave feminism: domesticity, virginity, and marriageability. (The first question winners were asked was when and what kind of man they would like to marry.) Even the sash itself was an appropriation of the suffragette sashes women wore to denote women’s collective political identity by state: the contestants wore them to signify individual identity, pitting women against each other regionally for a national title that rewarded appearance, not women’s agency or participation in national politics. So as a reactionary institution, each step of Miss America’s evolution tracks with some development in our culture, whether electoral politics, immigration, war, fashion, feminism or (once scholarships were added in the 1940s) women’s higher education.

But wherever you have a repressive institution, someone is going to rebel, and that’s where Miss America gets interesting. Especially in the early 20th century, when women had fewer professional opportunities and competed as a means to financial and social mobility, some ambitious and courageous women flouted the rules. One refused to wear a swimsuit during her reign, causing a pageant sponsor to withdraw and create the Miss Universe pageant. Others used the title for unexpected ends: for example, Miss America 1958 Marilyn Van Derbur revealed—despite the disapproval of the pageant director–that she was an incest survivor and to this day works to support survivors of sexual abuse. I quote her talking about how the social and physical discipline Miss America required was useful to her in “locking up” her body and containing the trauma she experienced at the hands of her father. It was something she—and other winners—had to unlearn for the sake of their own mental health.

At first glance, your three books cover very different subjects of women in history. Are there common themes that link them?

They all explore female subcultures in which women, under the boot of patriarchy, are trying to gain traction financially or professionally, or both. My book Bodies of Subversion: A Secret History of Women and Tattoo, is a feminist history of Western tattoo art. Tattooing has historically been not only a male dominated but also a very macho profession in Europe and the US; the women who broke in as artists starting in the early 20th century were up against tremendous resistance, and transformed this medium by adapting it, in the late 20th century, to specifically female ends, like mastectomy scar coverups or designs specific to the female form. My book The Blue Tattoo: The Life of Olive Oatman grew out of Bodies of Subversion, but it too describes a woman socially marginalized, having been tattooed on her chin as a member of the Mohave tribe, which adopted and raised her after her pioneer family’s death in a wagon train attack. She was pushed into the spotlight and became a reluctant—but very effective—public speaker in the late 1850s, at a time when women had only just started to campaign for their rights. So, like the other women I’ve written about, she was up against very stubborn expectations of women’s social roles, and transcended them in the process of recounting her bicultural life.

What are you working on now?

I’m at work on a book about another sort-of subculture: Quaker abolitionist feminists of the early 1880s.The two most powerful social movements of 19th century America—abolition and women’s suffrage—were dominated by Quaker women. From its birth in Britain in the 1620s, Quakerism encouraged women’s independent travel, preaching, and gender equality, priming them for lives of advocacy that ultimately helped end slavery and secure the vote for women. Some of these women are well-known–Lucretia Mott, the Grimké sisters, Susan B. Anthony, Abby Kelley, Lucy Stone—but the religious foundation of their activism is not. Likewise, dozens of lesser known, equally dauntless Quaker feminists shaped the course of antebellum history, notably the Black abolitionist Grace Bustill Douglass, a founder of the bi-racial Philadelphia Female Anti-Slavery Society in 1833. While it was African Americans themselves who launched and led the bravest fight and took the greatest risks in the push for abolition, Quaker women used their public platform to advance it, attempting—not always successfully—to build an intersectional movement.

A question from Margot: Relevant to your book Understanding Socialism:

What are the biggest misconceptions about socialism at play in contemporary politics (especially in the Trump administration)?

The two biggest factual misconceptions are that socialism and communism are the same thing and that any government-owned, -funded, or subsidized program is socialist. However, the most deep-seated misuse of socialism in politics today is based on fear rather than on misunderstanding.

Over the last hundred years, Americans have been both baffled and frightened by socialism. Periodic “red scares” have shaped America’s domestic and foreign policy at times of national crisis,* beginning in 1919 when Attorney General A. Mitchell Palmer was convinced that socialists were plotting to overthrow the government. Without evidence, he arrested thousands of communists, socialists, and anarchists—most of whom trouble organizing a small political party, let alone a revolution—and held them without trial. (I will leave you to draw comparisons or not as you choose.)

Today, the popular understanding of socialism is still shaped to a great degree by the Cold War, which was often described in terms of a battle to the death between good (capitalism) and evil (communism). As a result, many people equate socialism with an attack on American values, without reference to the many different forms and ideals it has encompassed over the centuries, and use “socialist” as an epithet with no particular meaning.

*Though it is an open question whether such red scares are the cause or the result of the crises they accompany.

***

Interested in learning more about Lydia and her work? Check out her website: https://margotmifflin.com/

***

Come back tomorrow for three questions and an answer with historical novelist Joan Fernandez, author of Saving Vincent, the story Jo Van Gogh.

March 9, 2025

Talking About Women’s History: Three Questions and an Answer with Lydia Moland

Lydia Moland is the author of Lydia Maria Child: A Radical American Life, a biography of one of 19th-century America’s fiercest abolitionists. She is the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Professor of Philosophy at Colby College in Maine and the author of books and articles on 19th-century German philosophy. Her work on Lydia Maria Child has appeared in the Wall Street Journal, the Washington Post, and the Boston Globe, among other venues. She is the recipient of grants from the National Endowment for the Humanities, the ACLS, and the American Academy in Berlin. The best thing she did on her last sabbatical was to take trapeze lessons. [Pamela here: That sounds like so much fun!]

Take it away, Lydia!

What path led you to Lydia Maria Child? And why do you think it is important to tell her story today?

I had been happily writing academic books about German philosophy before the 2016 election. At that point, I decided that I wanted my scholarship to reflect our new national reality, and I went looking for wisdom from an American woman who had faced a moral emergency in her country. I literally went to the Schlesinger Library at Harvard, which has an incredible collection of women’s history, and asked the librarians if they knew of any women philosophers who had also fought against slavery. Their help led me to discover Lydia Maria Child, one of the foremost abolitionists of the 19th century. Child’s example stunned me. Once convinced of the evils of slavery, Child took stock of her abilities and dedicated them to helping her country live up to its principles. Her primary talents were as a writer, so she wrote fiction, nonfiction, histories, biographies, and self-help books, all with the express purpose of cultivating democratic virtues. But she did not only write. She assisted those escaping slavery and faced down mobs of proslavery agitators. She organized antislavery fairs and raised money for freedpeople. She edited a national abolitionist newspaper, used her connections to support Black artists and authors, and farmed sugar beets in an attempt to undermine the value of cane sugar grown on plantations.

If people know anything about Child, they know that she wrote “Over the River and Through the Wood.” I was intrigued (and simultaneously somewhat enraged) by the fact that someone famous for a sentimental Thanksgiving poem was actually a radical reformer. I decided more people needed to learn more from her example, so I wrote Lydia Maria Child: A Radical American Life.

Child’s story is so important today because she is a brilliant example of someone who recognized her responsibility for her country’s democracy and met that responsibility at every turn. There were very dark times: times when it seemed the country was sliding further into authoritarianism and all hope was lost. Child also survived a decade of disengagement and depression after her editing of a national abolitionist newspaper ended in ruined friendships, an estranged husband, and a conviction that her life had been for nothing. She learned through bitter experience that pursuing political change requires us not just to take stock of our talents but to understand our limits. This knowledge enabled her, after this period of depression, to reengage and keep fighting for the rest of her life. I think this is a vital example for all of us today.

Your previous work focused on 19th century German philosophy. What was it like to write about a 19th-century female activist instead?

I had a fundamental insight going into this project that in order to devote yourself to ending a systematic evil at your country’s core, you would have to be thinking philosophically. That is: you would have to be asking big questions like “What is justice?” or “What is truth?” or “What does it mean to be human?” You’d have to have some deep underlying commitments that would sustain you when things got hard. And you’d have to make good arguments: to listen to people, understand where they were coming from, and then convince them to change their lives. Child was not officially a philosopher—she wouldn’t have been allowed to be, given her gender—but she was inspired by German philosophy, and she certainly thought philosophically. She asked big questions; she had deep underlying commitments; and she was a champion at helping her fellow white Americans see that the arguments that enabled them to condone or ignore slavery were flawed.

Someone once said that no real social change happens without philosophy, and I think that’s true. Philosophy has always been an enormous source of strength to me, including in my political engagements. As we confront social crises from climate change to racial injustice to growing threats to women’s rights, I think we can all benefit from the example of someone like Child.

What are you working on now?

Two things: one, together with Alison Stone of Lancaster University, I am editing the Oxford Handbook of American and British Women Philosophers in the Nineteenth Century. We were educated to think that there were no women philosophers in the nineteenth century. But once we started looking, they were everywhere. They had been erased or forgotten in all the ways with which we are now familiar. If we assume they were not there, we do not look for them. If we do not look for them, we do not find them! Our volume has 50 chapters bringing these amazing women back into the light. [Pamela butting in again: This is such a familiar, enraging story.]

And I have definitely been bitten by the biography bug! I have started work on the life of Helene Stöcker, a radical German feminist and pacifist who had to flee the Nazis in 1933. Stöcker was the first German woman to earn a PhD in philosophy. She used the radical thought of Friedrich Nietzsche (despite his famous and blistering misogyny!) to claim that society’s values needed radical reevaluation. She used this insight to attack norms that held women back; she also used it to challenge her society’s assumption that war could be justified. But she did not only theorize. Stöcker founded clinics for unwed mothers to give birth and homes for them to live. She organized seminars advising women on sexual health and petitioned the government to provide paid leave for new mothers. After World War I, she organized internationally for peace, collaborating with Albert Einstein and others in the hopes of preventing another war. When this failed, she escaped via the trans-Siberian railroad across Russia and took a steamer to San Francisco. It is a life of principle and adventure, and I am excited to get started!

A question from Lydia: Your book The Dragon from Chicago is also about a woman who, like my new biographical subject Helene Stöcker, lived and wrote in Berlin in the early 1900s. (Stöcker was also a well-known author, so I am sure they knew of each other!) Both women tried to warn their readers about rising fascism. How did you manage the emotionally draining aspects of writing about such dark times? Do you think about lessons for us today about how to encourage readers to do what’s necessary to resist political oppression?

First, let me say, it was indeed emotionally draining. One of the first things I did was read all of Sigrid Schultz’s by-lined articles in chronological order, from a fluffy little piece about her first visit to Paris after World War I, written in 1919, to a retrospective article on identifying Hitler’s body after the war, written in 1968. Reading the news day-to-day as the Weimar republic crumbled and the Nazis seized control was powerful and distressing, especially when the news then seemed all too similar to the news in 2020.

I found the best way to manage the emotional stress was to step away from the grim and dark in my down time. I chopped a lot of vegetables. I knitted simple things—knit four, purl four, repeat. I read a lot of genre novels–science fiction, fantasy, mystery, and romance were all fair game as long as they were not set in Nazi Germany.(Horror, not so much.) I ignored the many many people who told me I really needed to watch Babylon Berlin or World on Fire—sorry, folks, those were the last things I needed to watch. (Though I did indulge myself with a couple of seasons of Wonder Woman. Watching Lynda Carter kick Nazi butt in every episode was deeply satisfying.)

But giving myself downtime was not the same as hiding my head in the sand. I also spent a lot of time thinking about the ways in which Sigrid Schultz stood up to the Nazis , and wondering whether I would be as courageous as she was. Over and over I came back to her own assessment of the work she did: “The greatest service we could render our country was to try to marshal the facts as they were and not as propagandists tried to make them appear.” As a historian, that’s my assignment.

***

Interested in learning more about Lydia and her work?

Check out her website: lydiamoland.com

If you have access to the Wall Street Journal, read this review of Lydia Maria Child: “An Abolitionist is Born” (Pay wall, alas!)

Follow her on Bluesky: @lydiamoland.bsky.social

Read this piece about her new research on the feminist and pacifist Helene Stöcker

***

Come back tomorrow for three questions and an answer with Margot Mifflin, author of Looking for Miss America

March 6, 2025

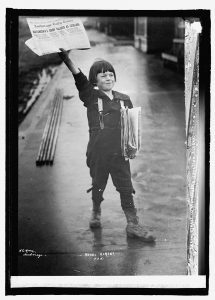

Rosie the Riveter’s Texas Cousins–and a Piece of Big News at the End!

Rosie the Riveter entered the American imagination in 1942 in a song by Redd Evans and John Jacob Loeb which celebrated a tireless factory worker and her riveting gun.* Artists quickly picked up the image for patriotic posters, the best known being J. Howard Miller’s “We Can Do It” poster for Westinghouse Electric.

But Rosie was only one version of the women who stepped up to do non-traditional jobs in World War II. The women who worked at Kelly Field in San Antonio were known locally as “Kelly Katies.” During the course of the war, Kelly Airfield became the world’s largest air supply depot; the 10,000 plus Katies who worked there made up more than forty percent of the workforce.* Among other jobs, they overhauled aircraft engines, taxied aircraft, and repaired damaged planes.

When the Korean War began in 1950, Katies returned to Kelly Field to overhaul B-29 bombers and other aircraft that were taken out of storage. You could argue that the Air Force took the Katies out of storage, too.

*This was news to me. This clip is from a 1943 recording of the song made by the Four Vagabonds.

**The first woman to work at Kelly, Estella Davis, arrived during the First World War, in December, 1917. (There’s got to be a story there.) She retired in September, 1945, at the age of 68, but only after she was sure she wasn’t needed to support the war effort.

*Takes a deep breath*

And now for my big news: The Dragon from Chicago is one of five finalists for the Los Angeles Times Book Prize in Biography. Needless to say, I am thrilled. (Thrilled!!!!) The winner will be announced on April 25, at a ceremony that kicks off the Los Angeles Times Festival of Books at the campus of University of Southern California. (I’ll be on a panel at the festival and signing books.) Cross your fingers for me, and drop by to say hi if you’re in the L.A. area.

Quite frankly, I already feel like a winner.

***

Come back on Monday for three questions and an answer with philosopher and historian Lydia Moland.

March 5, 2025

Talking About Women’s History: Three Questions and an Answer with Dava Sobel

Every year I gather up my courage to invite at least one writer whom I do not know and whose work is extraordinary. This year that writer was Dava Sobel. I fan-girled all over the house when she said yes.

Dava Sobel is the author of Longitude (Walker 1995, Bloomsbury 2005), Galileo’s Daughter (Walker 1999 and 2011), The Planets (Viking 2005, Penguin 2006), A More Perfect Heaven (Walker/Bloomsbury 2011 and 2012), And the Sun Stood Still (Bloomsbury 2016), The Glass Universe (Viking 2016, Penguin 2017) and The Elements of Marie Curie (Grove/Atlantic 2024). She has also co-authored six books, including Is Anyone Out There? with astronomer Frank Drake, and currently edits the “Meter” poetry column in Scientific American.

Take it away Dava!

Image credit: Glen Allsop for Hodinkee

How do you choose subjects for your books?

Choosing a subject for a book is a little like choosing a romantic partner. You’re going to be alone in a room together for a long time, through periods that will feel dark and discouraging, so it helps to really like or even love the topic. I can honestly say that I’ve fallen in love with all the people I’ve written about — or with the story their lives embody. Mme. Curie, the central figure of my most recent book, proved to be the perfect pandemic companion. Her grit had seen her through griefs and challenges far more threatening than any aspect of my situation, and I took inspiration daily from her example.

Of course there has to be science in the mix to attract me. Real chemistry, say, or the dawn of astrophysics. I enjoy learning about and then trying to explain aspects of science as a creative human enterprise. Everyone knows that scientists “do research,” but most people have no idea what such research might entail, or how it would feel to be the scientist at work in this laboratory or at that observatory.

Because I write about the history of science, and can’t interview the long dead, I rely on archives for letters and diaries. If those kinds of materials don’t exist, or they’re written in a language I can’t read, then I consider that topic out of reach. Sometimes the existence of such a trove is reason enough to take on a book project, as happened when I learned that Galileo’s elder daughter, who was a cloistered nun, had written her supposedly heretic father more than a hundred letters that still survived. I felt that familiar rush of excitement, and figured I could probably revive my three years of university-level Italian, despite the lapse of three decades. The fact that Galileo’s replies had vanished over the centuries seemed problematic at first, but he’d said enough in other contexts to carry his end of their conversation.

The Curie archives were physically out of reach because of travel restrictions during the pandemic. Fortunately, however, the fact of Marie’s fame as a two-time Nobel Prize winner, coupled with the dangerous nature of the materials she handled, had resulted in the digitization of nearly every notebook and draft letter, including the hand-written grief journal that she kept through the year following her husband’s death. The letters to and from her two daughters had been collected and published as books, so I had all of those at hand as well. The Elements of Marie Curie is a particularly female story — a tale of scientific discovery, yes, but also of love and marriage, childbirth, miscarriage, difficulty nursing, misogyny, and widowhood.

What is the most surprising thing you learned doing research for your books?

By far the most surprising — even shocking — thing was the discovery of my own misogyny. This happened rather late in my career, and explains my decision to tell only women’s stories going forward. Of course, as a woman, I didn’t think I could be accused of misogyny, but I was wrong.

I learned this while writing my previous book, The Glass Universe, which tells the story of a group of women who worked at the Harvard College Observatory in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, where they made pivotal discoveries in astronomy. I had written about many key figures in the history of astronomy, including Galileo and Copernicus, and the story of the Harvard women appealed to me precisely because it focused on female astronomers. However, once I got to work, each one’s achievements surprised me. And why was that? At length I had to admit that I’d come to them with embarrassingly low expectations. It seemed I didn’t really believe women could do science. In spite of the encouragement I’d enjoyed from my own family, at school, and through decades as a professional science writer, I had not escaped the negative attitudes about women that were “in the air” when I was growing up in the 1950s.

After that transformative moment of confronting my latent undiagnosed misogyny, all I wanted to do was tell true stories that reveal women’s scientific prowess. When I learned that some 45 women had spent a formative period in Mme. Curie’s lab, I knew I had something new and important to say about her.

Two of your books, The Glass Universe and The Elements of Marie Curie, are group biographies. How did you decide which women to include?

The Harvard Observatory women numbered in the dozens, but only five of them achieved lasting fame (at least in the astronomical community) for their contributions. Still, five main female characters are a lot, plus the charismatic director who hired them, and the two wealthy heiresses who funded their research. I longed for one stand-out who could carry the whole story, but she didn’t exist. Eventually it struck me that the several hundred thousand glass-plate photographs of the night sky, which replaced direct observation by telescope for these women, connected everything and everyone in the story. That gave me the idea for the title, since the collection of plates is truly a “glass universe.” And of course the glass universe — very fittingly — encompassed the notion of the glass ceiling. In fact, the association is so strong that people often call the book “The Glass Ceiling” without realizing they’ve misspoken.

I had the opposite problem with Mme. Curie. She is a figure of such towering fame that nearly everyone has heard of her. Although she was never the only woman scientist, she’s the only one most people can name. My initial idea was to put her in the background of the narrative. Since the women arrived at the lab in a slow trickle at first, one per year, I thought I’d treat each one individually, moving chronologically and bringing in the facts of Mme. Curie’s life only as they related to her protegees’ experiences. That didn’t work at all. My editor, George Gibson, reminded me that although virtually everyone knew Mme. Curie’s name, her name was all they knew. Her personal story had to be the vehicle that carried all the others’ stories.

As with The Glass Universe, an inanimate character also figures in this book. It’s the periodic table of the elements. Each chapter title has two parts: the name of a person (usually a woman in the Curie lab, though occasionally a man) and the name of an element relevant to that person’s work.

My choices of individuals to feature depended partly on the importance or interest of their activities and partly on the amount of available information about them. Some of Mme. Curie’s female assistants flitted through the lab so quickly that they left no historical record, not even their full names. I’m still wondering whatever happened to the mysterious “Mlle. Larch.”

A question from Dava: Is Women’s History Month a good thing or a bad thing? Please elaborate.

I struggle with this question every March. And every March, my answer remains the same. It is neither good nor bad. But for now it is necessary. In fact, I would argue that it is more necessary than ever. As I write this, Federal agencies are ordering celebration of “cultural awareness” months paused or cancelled altogether. (Perhaps by the time you read this those orders will have been rolled back. We can only hope.)

In the meantime, I intend to celebrate Women’s History month as hard as I can. The fact is that that many libraries, museums, and particularly schools only include women in their programming in March. Until we regularly teach students that women were involved in, well, everything, we need Women’s History Month.

Let’s party hard!

***

Interested in learning more about Dava Sobel and her work? Check out her website at http://www.davasobel.com/

***

Tomorrow will be business as usual here on the Margins with a blog post from me. Then we’ll be back on Monday with three questions and a answer from philosopher and historian Lydia Moland.

March 4, 2025

Talking About Women’s History: Three Questions and An Answer with Michele C. Hollow

Michele Hollow and I met many years ago when we were both new members of the American Society of Journalists and Authors. We’ve been following each other around the internet ever since, cheering each other on.

Michele is an award-winning writer and editor. She writes about health, mental health, autism, aging, animals, and climate. Her byline has appeared in The New York Times, Next Avenue, The Guardian, Parents, AARP, and The Costco Connection. She has also done nonprofit writing for IFAW (International Fund for Animal Welfare), Family Promise (a nonprofit that helps homeless families), and the Simons Foundation (an autism research nonprofit).

She is the author of The Everything Guide to Working with Animals (Adams Media), which came out in March 2009, and a middle grade biography on the Grateful Dead, which was updated and reissued in 2019. Her first historical novel for middle grade readers came out on September 10, 2024. It’s called Jurassic Girl and is about Mary Anning’s first major fossil discovery at age 12. This was back in 1811. The men in the London Geological Society called her a fraud; they didn’t believe a girl could make such an amazing find. Mary triumphed and today she’s known as the “Mother of Paleontology.”

Michele lives in NJ with her husband, Steven, and their rescue cat Chai. She has two sons.

Take it away, Michele:

What path led you to Mary Anning? And why do you think it is important to tell her story for younger readers today?

As a journalist, I enjoy writing about people who make a difference. I write about animal welfare and health. Interviewing everyone from a professional violinist who serenades formerly abused dogs at the ASPCA on his day off to professional clowns and vaudevillians who bring joy and laughter to Alzheimer patients at hospitals uplifts my spirit. I like getting to know people who help others.

A couple of my readers told me about Mary Anning. I had not heard of her. I did a bit of digging online. A handful of sites popped up. I learned she was a fossil hunter who discovered an ichthyosaurus, which translates to fish lizard. I later found out the ichthyosaurus is neither a fish nor a lizard. It’s in the reptile family.

What struck me about this discovery was that at the time, no one was certain what she found. Many people in her hometown of Lyme Regis, UK, thought it was a crocodile. This was in 1811 when Mary was 12 years old. Imagine being 12 and unearthing a creature no one has seen before. This was at a time when most people didn’t believe in extinction. They didn’t believe an entire species would die out.

In addition to making such a major discovery at age 12, Mary was poor and self-educated. Back then most people paid to attend school. Mary’s family didn’t have money to send her or her brother Joseph to school.

Many of the men at London’s Geological Society thought Mary was a fraud. Females did not get credit in scientific journals back then. The London Geological Society credited the man who purchased the fossil from Mary as the discoverer.

I wrote Jurassic Girl for middle grade students because Mary was a remarkable 12-year-old. I believe children would find her story relatable. Often young children don’t get the credit they deserve from adults. Reading about Mary’s perseverance and triumphs encourage readers of all ages.

How do you walk the line between historical fact and fiction in an historical novel?

This was the tricky part. I work as a journalist. One of the first internships I had while in college was working in the research department of the Time Life building in New York City. When I write articles, I interview experts and people experiencing issues that we can learn from.

I don’t own a time machine so I couldn’t go back in time and interview Mary or any of her family. I looked up books about Mary and found The Fossil Hunter by Shelley Emling. It’s a biography about Mary Anning.

While reading the book, I learned about the Lyme Regis Museum. About a year ago, the museum opened a Mary Anning wing. Lyme Regis is part of the Jurassic Coast. Today, tourists fossil hunt at the same seaside that Mary did more than 200 years ago.

The Fossil Hunter mentioned the research team at the Lyme Regis Museum. I contacted them, told them I was writing a book about Mary, and asked if I could send them questions. I sent lots of questions, and the researchers at the museum were kind enough to answer them.

In my book’s introduction, I told my readers that facts are important when writing about history and historical figures. I stated I couldn’t interview Mary or anyone else from that period so made up the dialogue. That’s where the “fiction” part comes in.

When you talk to children about Mary Anning, what surprises them most about her story?

Most here in the U.S. are not aware of her. In the UK, Jurassic Girl is doing well because many people there know about her. Last year the UK introduced a Mary Anning postage stamp.

What stood out to me was a recent interaction I had with other science writers. A few female writers complained that women scientists don’t always get credit for their work in scientific journals. Women in science even today have to fight for recognition.

When I addressed four fourth grade classes at an elementary school, many of the girls came up to me at the end of my talk, raised a fist, and said “Girl Power!” I believe girls understand that doors aren’t always open.

This statue in New York City is named “Dinosaur,” acknowledging the relationship between dinosaurs and modern pigeons.

The girls and the boys I talk to at schools love learning about Mary Anning. Many have read and enjoyed Jurassic Girl. They love everything having to do with dinosaurs. They understand that dinosaurs evolved into birds. I tell them if they want to see a live dinosaur to go outside and watch the pigeons and other birds in their neighborhoods.

My readers are smart.

A question from Michele: I’m curious if you have discussed The Dragon from Chicago with children. I know it’s for adults. I believe young adults and mature children would find the book fascinating. So, if you are so inclined, how would you talk to children about Sigrid Schultz?

I think the odds that anyone would ask me to talk to elementary school students about Sigrid Schultz are small, particularly in today’s world when there is an impulse to protect children from learning about the bad stuff. That said, if I were given the opportunity I would focus on three big-picture issues: what the newspaper business was like for women in the early to mid twentieth century, Sigrid’s courage in reporting on the Nazis, and the importance of reporters in keeping readers informed about what is happening in the world.

***

Interested in learning more about Michele C Hollow and her work?

Check out some of her articles here

Check out her web page about Jurassic Girl here:

Buy Jurassic Girl here

Follow her on Bluesksy: @michelechollow.bsky.social

Follow her on Facebook: Michele C Hollow

***

Come back tomorrow for three questions and an answer with best-selling science writer Dava Sobel, whose most recent book deals with Marie Curie and the forgotten women scientists who worked with her.

March 3, 2025

Talking About Women’s History: Three Questions and an Answer with Vanda Krefft

Vanda Krefft is the author of Expect Great Things!, a social history of the famed Katharine Gibbs School and its impact on the American workplace for women. The book tells the lively, unlikely story of Katharine Gibbs herself and celebrates the many pathfinding achievements of her school’s graduates during the early to mid-20th century. Expect Great Things! (Algonquin Books, 2025) is available today wherever you buy or order your books.

Vanda’s previous book,The Man Who Made the Movies (HarperCollins, 2017), is the first in-depth biography of Twentieth Century Fox founder William Fox and reveals Fox’s many pivotal contributions to the American film industry as well as the shocking events that ended his career. Previously, Vanda wrote about the entertainment industry for leading national magazines and syndicated news services. Her work has appeared in Elle, Redbook, Woman’s Day, Woman’s World, and the Los Angeles Times.

Take it away, Vanda!

What path led you to the Katharine Gibbs School?

I like people who come out of nowhere and do the unexpected. My first book, The Man Who Made the Movies (HarperCollins, 2017), was a biography of 20th Century Fox founder William Fox, who created one of Hollywood’s great movie studios and profoundly shaped not only the art of film, but also the industry’s technology and business structure. Fox grew up in dire poverty on New York’s Lower East Side and had only a third-grade education. Similarly unlikely was the success of Katharine Gibbs and her elegant, landmark school for women.

I had been vaguely familiar with the Katharine Gibbs School, which had its glory days in the mid-20th century and which, after the Gibbs family sold the business in 1968, slowly slid downhill under corporate ownership until permanently closing in 2011. When a friend suggested Katharine Gibbs as a subject for my second book, I was skeptical. I’d always assumed that founder Katharine Gibbs was a stuffy, conservative, Seven Sisters-type New England aristocrat—nothing like jumping to conclusions based on a name!—and that her school aimed to suppress young women’s ambitions by training them as secretaries. Quite the opposite, I discovered, after doing some preliminary research. In fact, Katharine Gibbs came from a small Midwestern town where her father slaughtered hogs for a living, had only a high school education, and had never worked outside the home before finding herself a near-broke middle-aged widow.

In fact, she started her school not to reinforce the status quo but to upend it. Having been betrayed three times by her belief that male family members would always provide for and protect her financially—the last straw was her husband’s dying in 1909 without a will—she was determined that what had happened to her should never have to happen to any other woman. And so, tapping long-dormant assertiveness and courage, Katharine Gibbs built a tremendously successful business with principal locations on New York’s Park Avenue and in Boston’s Back Bay.

Her mission: to give women the skills and knowledge so they could always earn a good, independent living. In an era replete with gender bias, she figured, that meant training them to use executive secretary positions as a springboard into management. Students learned not only typing and stenography, but also academic subjects taught by professors from elite universities. A sort of Trojan Horse campaign, it worked. Among the 50,000 Gibbs graduates by 1968, many became leaders across all facets of American life. It was deeply rewarding to tell the stories of these “hidden figures” of the women’s movement who helped lay the foundation for today’s more equitable working world.

We’re all familiar with the challenges of finding sources for writing about women from the distant past. What are the challenges of writing about women from the early and middle twentieth century?

Massive challenges! In general, my ladies—yes, “ladies,” because in their era, the term primarily connoted discernment, graciousness, and consideration for others—were not firebrands or banner-carrying feminists. They were women who started in the trenches, typing and taking dictation, and worked their way up gradually to leadership positions. At Gibbs, they were trained to camouflage their ambitions with a smile, correct speech, cooperation, and a ladylike hat and white gloves. (That didn’t mean they were pushovers or doormats. The Gibbs placement office assured them they could always quit, with another good opportunity ready at hand.) But because Gibbs women worked within a culture that generally regarded female employees as inferior and/or biding their time till they landed a husband, their achievements were often ignored.

For instance, having learned that in 1930, Gibbs graduate Mary Sutton Ramsdell became one of the first two female Massachusetts State Police patrol officers, I thought that surely the Boston Globe would have covered such a milestone event. Yet not a word on its pages, let alone a photo. Likewise, I found nothing of any substance in mainstream publications about Joan M. Clark who, with her Gibbs education but no college degree, rose from a secretarial job with the US army to become Ambassador to Malta and then head of the US Foreign Service.

But thank goodness for the internet and its rich, deep, and sometimes obscure resources. Via ancestry.com, historical newspaper databases, and unending Google searches, I tracked down family members and friends of Gibbs graduates, found oral histories in archival collections, and located some extensive collections of personal papers in university libraries. Here was one advantage of the time frame. Newspapers proliferated in the US before and during the early days of television. While overwhelmingly they tended to report on women only when they got engaged or married, once in a while I found breadcrumb information about dates, family history, and employment.

Following those clues led to first-hand interviews with Gibbs graduates and their descendants. While some former students were in their eighties or nineties, all those I reached were mentally sharp, with vivid recollections, good humor, and unfailing cooperation—delightful to speak with. Their family members and friends were also extremely helpful, providing illuminating personal details. I would encourage anyone researching this time frame to act fast to get firsthand testimony. Write a letter, pick up the phone, send emails to potential sources and people who knew them (and keep trying if you don’t get an answer right away), ask about scrapbooks and photos and other memorabilia, ask who else might be helpful. Yours may be the last chance to save a valuable piece of the past.

Was there a woman you were sad to leave out?

Not one, but many. The ones I didn’t know about because their achievements hadn’t turned up anywhere in my research. I’m sure there were many unrecognized, uncelebrated Gibbs graduates. One of my early research tasks was to go to Brown University’s Hay Library, home of the Katharine Gibbs School Records, where I scanned every single page of every single Gibbs yearbook they had. It wasn’t a complete collection, and some of the branches of the school didn’t have yearbooks, but something was better than nothing. As I looked at the student headshots and read their comments, it was clear that these young women had great energy, optimism, and potential. But so many times, when I searched beyond for information about them, nothing turned up.

Among the Gibbs women I did profile, I regretted not being able to tell the full story of Myrna Custis. There she was, a lone Black face among the students in the 1956 yearbook of the New York Gibbs School. Race was a complicated issue for the Gibbs School in these mid-century years. I found no evidence that school ever discriminated on the basis of race, religion, or ethnic background. To the contrary, all indications were that the faculty advocated progressive social attitudes—such as pushing back if a boss tried to dissuade them from hiring a Black employee.

Among the Gibbs women I did profile, I regretted not being able to tell the full story of Myrna Custis. There she was, a lone Black face among the students in the 1956 yearbook of the New York Gibbs School. Race was a complicated issue for the Gibbs School in these mid-century years. I found no evidence that school ever discriminated on the basis of race, religion, or ethnic background. To the contrary, all indications were that the faculty advocated progressive social attitudes—such as pushing back if a boss tried to dissuade them from hiring a Black employee.

More likely, the fact that Myrna Custis was the first Black student to appear in the extant Gibbs yearbooks reflected grim socio-economic facts. That is, the Gibbs School was expensive and most Black families earned substantially less than white families. Then why didn’t the school offer scholarships to help recruit Black students? That raises another, thornier question: would it have been ethical to take two years of a young woman’s life to encourage her hopes and prepare her for a job that almost certainly wouldn’t exist for her upon graduation? The Gibbs placement department well knew the attitudes of employers and no laws as yet prohibited racial discrimination.

I would have loved to ask Myrna or her family members what led her to enroll at Gibbs, what dreams she had then, how the other students and faculty treated her, and what happened to her out in the working world.

For all the Gibbs stories that I missed, I hope that readers will contact me to fill me in on more of this important hidden history. (https://www.vandakrefft.com/contact)

A question from Vanda: You know so much about otherwise forgotten or marginalized women’s history—was there anything in the book that surprised you?

I can honestly say that the biggest surprise was the underlying mission of the school. Even though I was aware of the fact that executive secretaries were (and are) often powerful figures in the organizations they worked for, I, too, assumed that the school was fundamentally conservative in its goals. Once I let go of that assumption, I was ready to be amazed. (And you did in fact amaze me, over and over again.)

One story in particular caught my imagination: Joye Hummel, who was an important writer in the early days of the Wonder Woman comics. Her story was definitely downplayed in other accounts I had read about the creation of my favorite super hero!

***

Interested in learning more about Vanda and her work? Check out her website at https://www.vandakrefft.com/

***

Come back tomorrow for three questions and an answer with Michele C. Hollow, the author of Jurassic Girl.

Talking About Women’s History: Threee Questions and an Answer with Vanda Krefft

Vanda Krefft is the author of Expect Great Things!, a social history of the famed Katharine Gibbs School and its impact on the American workplace for women. The book tells the lively, unlikely story of Katharine Gibbs herself and celebrates the many pathfinding achievements of her school’s graduates during the early to mid-20th century. Expect Great Things! (Algonquin Books, 2025) is available today wherever you buy or order your books.

Vanda’s previous book,The Man Who Made the Movies (HarperCollins, 2017), is the first in-depth biography of Twentieth Century Fox founder William Fox and reveals Fox’s many pivotal contributions to the American film industry as well as the shocking events that ended his career. Previously, Vanda wrote about the entertainment industry for leading national magazines and syndicated news services. Her work has appeared in Elle, Redbook, Woman’s Day, Woman’s World, and the Los Angeles Times.

Take it away, Vanda!

What path led you to the Katharine Gibbs School?

I like people who come out of nowhere and do the unexpected. My first book, The Man Who Made the Movies (HarperCollins, 2017), was a biography of 20th Century Fox founder William Fox, who created one of Hollywood’s great movie studios and profoundly shaped not only the art of film, but also the industry’s technology and business structure. Fox grew up in dire poverty on New York’s Lower East Side and had only a third-grade education. Similarly unlikely was the success of Katharine Gibbs and her elegant, landmark school for women.

I had been vaguely familiar with the Katharine Gibbs School, which had its glory days in the mid-20th century and which, after the Gibbs family sold the business in 1968, slowly slid downhill under corporate ownership until permanently closing in 2011. When a friend suggested Katharine Gibbs as a subject for my second book., I was skeptical. I’d always assumed that founder Katharine Gibbs was a stuffy, conservative, Seven Sisters-type New England aristocrat—nothing like jumping to conclusions based on a name!—and that her school aimed to suppress young women’s ambitions by training them as secretaries. Quite the opposite, I discovered, after doing some preliminary research. In fact, Katharine Gibbs came from a small Midwestern town where her father slaughtered hogs for a living, had only a high school education, and had never worked outside the home before finding herself a near-broke middle-aged widow.

In fact, she started her school not to reinforce the status quo but to upend it. Having been betrayed three times by her belief that male family members would always provide for and protect her financially—the last straw was her husband’s dying in 1909 without a will—she was determined that what had happened to her should never have to happen to any other woman. And so, tapping long-dormant assertiveness and courage, Katharine Gibbs built a tremendously successful business with principal locations on New York’s Park Avenue and in Boston’s Back Bay.

Her mission: to give women the skills and knowledge so they could always earn a good, independent living. In an era replete with gender bias, she figured, that meant training them to use executive secretary positions as a springboard into management. Students learned not only typing and stenography, but also academic subjects taught by professors from elite universities. A sort of Trojan Horse campaign, it worked. Among the 50,000 Gibbs graduates by 1968, many became leaders across all facets of American life. It was deeply rewarding to tell the stories of these “hidden figures” of the women’s movement who helped lay the foundation for today’s more equitable working world.

We’re all familiar with the challenges of finding sources for writing about women from the distant past. What are the challenges of writing about women from the early and middle twentieth century?

Massive challenges! In general, my ladies—yes, “ladies,” because in their era, the term primarily connoted discernment, graciousness, and consideration for others—were not firebrands or banner-carrying feminists. They were women who started in the trenches, typing and taking dictation, and worked their way up gradually to leadership positions. At Gibbs, they were trained to camouflage their ambitions with a smile, correct speech, cooperation, and a ladylike hat and white gloves. (That didn’t mean they were pushovers or doormats. The Gibbs placement office assured them they could always quit, with another good opportunity ready at hand.) But because Gibbs women worked within a culture that generally regarded female employees as inferior and/or biding their time till they landed a husband, their achievements were often ignored.

For instance, having learned that in 1930, Gibbs graduate Mary Sutton Ramsdell became one of the first two female Massachusetts State Police patrol officers, I thought that surely the Boston Globe would have covered such a milestone event. Yet not a word on its pages, let alone a photo. Likewise, I found nothing of any substance in mainstream publications about Joan M. Clark who, with her Gibbs education but no college degree, rose from a secretarial job with the US army to become Ambassador to Malta and then head of the US Foreign Service.

But thank goodness for the internet and its rich, deep, and sometimes obscure resources. Via ancestry.com, historical newspaper databases, and unending Google searches, I tracked down family members and friends of Gibbs graduates, found oral histories in archival collections, and located some extensive collections of personal papers in university libraries. Here was one advantage of the time frame. Newspapers proliferated in the US before and during the early days of television. While overwhelmingly they tended to report on women only when they got engaged or married, once in a while I found breadcrumb information about dates, family history, and employment.

Following those clues led to first-hand interviews with Gibbs graduates and their descendants. While some former students were in their eighties or nineties, all those I reached were mentally sharp, with vivid recollections, good humor, and unfailing cooperation—delightful to speak with. Their family members and friends were also extremely helpful, providing illuminating personal details. I would encourage anyone researching this time frame to act fast to get firsthand testimony. Write a letter, pick up the phone, send emails to potential sources and people who knew them (and keep trying if you don’t get an answer right away), ask about scrapbooks and photos and other memorabilia, ask who else might be helpful. Yours may be the last chance to save a valuable piece of the past.

Was there a woman you were sad to leave out?

Not one, but many. The ones I didn’t know about because their achievements hadn’t turned up anywhere in my research. I’m sure there were many unrecognized, uncelebrated Gibbs graduates. One of my early research tasks was to go to Brown University’s Hay Library, home of the Katharine Gibbs School Records, where I scanned every single page of every single Gibbs yearbook they had. It wasn’t a complete collection, and some of the branches of the school didn’t have yearbooks, but something was better than nothing. As I looked at the student headshots and read their comments, it was clear that these young women had great energy, optimism, and potential. But so many times, when I searched beyond for information about them, nothing turned up.

Among the Gibbs women I did profile, I regretted not being able to tell the full story of Myrna Custis. There she was, a lone Black face among the students in the 1956 yearbook of the New York Gibbs School. Race was a complicated issue for the Gibbs School in these mid-century years. I found no evidence that school ever discriminated on the basis of race, religion, or ethnic background. To the contrary, all indications were that the faculty advocated progressive social attitudes—such as pushing back if a boss tried to dissuade them from hiring a Black employee.

Among the Gibbs women I did profile, I regretted not being able to tell the full story of Myrna Custis. There she was, a lone Black face among the students in the 1956 yearbook of the New York Gibbs School. Race was a complicated issue for the Gibbs School in these mid-century years. I found no evidence that school ever discriminated on the basis of race, religion, or ethnic background. To the contrary, all indications were that the faculty advocated progressive social attitudes—such as pushing back if a boss tried to dissuade them from hiring a Black employee.

More likely, the fact that Myrna Custis was the first Black student to appear in the extant Gibbs yearbooks reflected grim socio-economic facts. That is, the Gibbs School was expensive and most Black families earned substantially less than white families. Then why didn’t the school offer scholarships to help recruit Black students? That raises another, thornier question: would it have been ethical to take two years of a young woman’s life to encourage her hopes and prepare her for a job that almost certainly wouldn’t exist for her upon graduation? The Gibbs placement department well knew the attitudes of employers and no laws as yet prohibited racial discrimination.

I would have loved to ask Myrna or her family members what led her to enroll at Gibbs, what dreams she had then, how the other students and faculty treated her, and what happened to her out in the working world.

For all the Gibbs stories that I missed, I hope that readers will contact me to fill me in on more of this important hidden history. (https://www.vandakrefft.com/contact)

A question from Vanda: You know so much about otherwise forgotten or marginalized women’s history—was there anything in the book that surprised you?

I can honestly say that the biggest surprise was the underlying mission of the school. Even though I was aware of the fact that executive secretaries were (and are) often powerful figures in the organizations they worked for, I, too, assumed that the school was fundamentally conservative in its goals. Once I let go of that assumption, I was ready to be amazed. (And you did in fact amaze me, over and over again.)

One story in particular caught my imagination: Joye Hummel, who was an important writer in the early days of the Wonder Woman comics. Her story was definitely downplayed in other accounts I had read about the creation of my favorite super hero!

***

Interested in learning more about Vanda and her work? Check out her website at https://www.vandakrefft.com/

***

Come back tomorrow for three questions and an answer with Michele C. Hollow, the author of Jurassic Girl.

March 2, 2025

Talking About Women’s History: Three Questions and an Answer with Sara Catterall

Sara Catterall and I have been following each other around the internet since we met as reviewers for Shelf Awareness, a shockingly long time ago. I’ve been looking forward to her biography of Amelia Bloomer ever since she began posting about it. As you’ll see below, bloomers were only a small part of Bloomer’s life.

Sara is a writer with a Drama degree from NYU, and an MLIS from Syracuse University. She was born in Ankara and grew up in South Minneapolis. She has worked as a librarian at Cornell University, as a reviewer and interviewer for Shelf Awareness, and as a professional book indexer. Her work has been published in the NEH’s Humanities magazine and The Sun, and she co-authored Ottoman Dress and Design in the West: A Visual History of Cultural Exchange. She lives with her family near Ithaca, New York, serves on the Executive Board of Buffalo Street Books in Ithaca, and is a member of Biographers International.

Take it away, Sara!

Photo credit: Edna Brown

Many of my readers will recognize the name Amelia Bloomer. Are there particular challenges in writing about women who people think they know something about?

I think that her name recognition helped me more than challenged me. I was first inspired to look up more about her because of it. Once I realized there was much more to her career, I kept a file of misinformation about her starting in 1851 right up to the current news. And I thought a lot about what those wrong ideas served, and why on earth people are still repeating them after so long. Why she comes up more often than some of her much more influential or scandalous peers. Also, though that viral incident of the “short dress and trousers” is far from her whole story, it does echo through her life. And they make a great hook! Even when people haven’t heard of Bloomer, they have heard of bloomers.

The thing most of us know about Amelia Bloomer is her championship of “rational dress” in the form of the “bloomers” that came to bear her name. How did dress reform fit into her larger career as a suffragist and social advocate?

In the more general sense of her advocacy for women’s personal and political freedom. She never considered dress reform one of her primary causes. She came to it by way of alternative medicine. Bloomer was chronically ill herself, with serious GI issues and daily headaches starting in her youth, possibly because of a bad bout of malaria, and possibly because of the mercury treatments that were common at that time. Tight clothes are fine when you’re healthy, but if you aren’t, and a lot of people had uncurable chronic ailments in the 19th century, switching to loose clothes can give some relief. “The Turkish dress” had been worn by white women since the 18th century as a political statement and for exercise and leisure, and was considered a feminine alternative to the clothing men wore. Also, in the 1840s, women’s clothing was not just tight, it was heavy and the hemlines trailed on the ground, which made it hard to work or walk in. Bloomer gave up corsets before she put on “the Turkish Dress” and she blamed her sister’s postpartum death on burdensome clothing. She was also known for walking so fast everywhere that her own husband, who was nearly a foot taller, could barely keep up with her. So the short dress and trousers appealed to Bloomer and her friends, and to other women who wore it before she did, for their physical comfort and freedom, without giving up modesty. You had to be a nonconformist, that’s for sure, but some women who wore it were not in favor of woman suffrage, and some women who kept wearing long skirts, were.

What is the most surprising thing you found doing research for your work?

So many! But one was how broad-minded Bloomer was about gender expression through clothes, given that she was born in 1818 and had a conservative rural upbringing. She had no problem with the idea of men wearing “women’s clothes” if they found them comfortable and liked them. Another was her clash with Frederick Douglass, and her friends Elizabeth Cady Stanton, and Susan B. Anthony, over the question of allowing men to be controlling officers in the one-year-old New York Women’s Temperance Society. Douglass, Stanton, and Anthony wanted the most educated, experienced, and influential officers possible, which at that time mostly meant men, and they wanted to focus on women’s rights rather than temperance. Bloomer felt that it was wrong to change the mission of the organization after a year of fundraising for a woman-controlled temperance society, and that women needed to keep control of the funds and the power for a while to gain confidence and learn how to manage an organization. This incident is well documented, including Douglass’s aggravated report of the meeting in his paper, and her reply in hers, but as far as I could see, no-one had written it up before.

Great cover!

A question from Sara: Other than Bloomer and Sigrid Schultz (I loved The Dragon From Chicago and gave it to friends for Christmas!), who are some Midwestern historical women that you think deserve a more national fame than they’ve had so far?

How to chose?

The first one that comes to mind is Indiana-born novelist Gene Stratton Porter (1863-1924). I first read one of her novels, A Girl of the Limberlost when I was nine or ten. I still read it every year or two. The more I learn about her, the more amazing she is. She was a best-selling novelist in the early twentieth century, an early conservation activist, and one of the first women to form a movie production company.

***

Interested in learning more about Sara Catterall and her work?

Check out her website: https://saracatterall.com/

Follow her on Bluesky: @scatterall.bsky.social

Follow her on Instagram: saracatterall

Buy the book here,or at your favorite purveyor of books.

***

Come back tomorrow for three questions and an answer with Vanda Krefft, author of Expect Great Things, the history of the surprisingly subversive Katharine Gibbs School.