Pamela D. Toler's Blog, page 10

February 27, 2025

Kicking off Women’s History Month a Day Early with Four Questions and an Answer with Amy Reading

In case you missed the memo, or got a memo that says otherwise, March is Women’s History Month.

We’re going to celebrate here in the Margins the same way we’ve celebrated for the last six (!) years, with a series of mini-interviews with people who write about or otherwise work with women’s history. Unlike the rest of the year, there will be new posts Monday through Friday. (If you want to rev yourself up, you can read all the previous interviews here.)

I’ve got a great mix of people lined up to talk about a wide range of women and historical projects. It’s going to be Big Fun!

In fact I’m so excited about the prospect that we’re going to start a day early in celebration of the 100th birthday of The New Yorker. The magazine plays a central role in Amy Reading’s book, The World She Edited: Katharine S. White at The New Yorker, which is a finalist for the National Book Critics Circle Award for Biography.

Amy is also the author of The Mark Inside: A Perfect Swindle, a Cunning Revenge, and a Small History of the Big Con. Her work has been supported by fellowships from the National Endowment of the Humanities and the New York Public Library, among others. She lives in upstate New York, where she serves on the board of her local independent bookstore, Buffalo Street Books. Her name is an aptonym. (Pamela here: I’ll save you the bother of looking it up. According to the Oxford English Dictionary an aptonym is “a person’s name that is regarded as amusingly appropriate to their occupation.” How fun is that?)

Take it away, Amy!

Photo credit: Jamie Love

Writing about a historical figure like Katharine White requires living with her over a period of years. What was it like to have her as a constant companion?

I began researching Katharine White’s life and career in 2017, and I immediately knew I could settle in comfortably for a long journey because she felt familiar to me. I get her mind. She was, like me, first and foremost a reader and she felt most herself when reading with a pencil in hand, whether to edit a manuscript or to notate a book. Criticism was her love language or, to put it another way, she had an editorial mindset about nearly everything in her life. Many people know her from her garden columns in The New Yorker and her posthumously published book, Onward and Upward in the Garden, but what is gardening except editing the landscape?

I came to understand how her editorial mindset could feel to her like generosity and abundance, like she was always in pursuit of a higher vision and bringing others along with her. This vision applied, first of all, to the magazine as a whole. She joined the staff just a few months after it was founded in 1925 when it was still a scrappy humor magazine, and she was the person most responsible for expanding its purview to more serious literature, memoir, and poetry. And of course her vision also applied to the manuscripts that arrived in the mail in huge stacks every day. She was so unbelievably good at reading something and seeing the outlines of what it could become. Her authors adored her for it—there are so many letters in the archives that testify to this.

The arc of Katharine’s life was unfailingly interesting for me in the eight years it took to research, write, and publish her biography. She graduated from Bryn Mawr in 1914 and she campaigned for suffrage, but she did not use the term “feminist” to describe herself, and her career took place almost exactly in the interval between the Nineteenth Amendment and The Feminine Mystique, an interval when women’s activism slackened. Yet she published a dazzling array of women authors who became canonical—Kay Boyle, Mary McCarthy, Jean Stafford, Elizabeth Bishop, Adrienne Rich, just to name a few—and furthermore, she corresponded with an impressive network of literary women, agents and editors who helped create the literature that women just like themselves were reading. I was riveted to the changes of Katharine’s career over time, to how she responded to changes in the workforce and changes in the culture at large. It’s not a bad idea as a historian to look at the editors who were themselves looking at their own times with critical, discerning eyes. And in Katharine’s case, that sense of being part of the slipstream of her times was doubled. Her marriage to E.B. White and his own career at The New Yorker meant that both people in that partnership were attuned to the news and their own roles in shaping, responding to, and commenting on it.

We’re all familiar with the challenges of finding sources for writing about women from the distant past. What are the challenges of writing about women from the early and middle twentieth century?

I was drowning in sources for Katharine’s life. As a literary woman in the era of typewriters, carbon copies, and secretaries who took dictation, her life and career has been very well documented and preserved. Too well! The New Yorker papers live at the New York Public Library, and just this month the NYPL has put treasures from this archive on exhibit to mark the magazine’s 100th anniversary. Here (second picture) is a note from Katharine White to her boss, Harold Ross. These papers felt nearly bottomless to me. I joked that Katharine’s editorial memos are like bindweed: I’d pull one folder out of the box, and three more folders would grow deep in the archive. My challenge was to forge a path through these papers, to find the authors who particularly mattered to her or who told a story that readers particularly needed to hear. That’s the challenge of any biography: to give shape to a life that is full to bursting in the living of it.

The New Yorker papers weren’t my only source. Katharine spent her retirement creating five distinct archives (her papers, her husband E.B. White’s, her sister Elizabeth Shepley Sergeant’s, and papers from both her mother’s and her father’s families) which she donated to four universities. She would often jot down a note, sometimes small and sometimes running to many pages, to explain why a particular letter was important, and then she’d paperclip the note to the letter, thus expanding her archive even more. It felt as if I were reading every source over her shoulder and that was both a blessing and a curse. Letters and notes within these archives make very clear that she destroyed sources even as she notated and preserved others. I learned about some of the most important moments of her personal life only from letters that escaped her attention or were donated after her death.

But the depth and breadth of these sources arise from privilege, and so the other challenge of writing about Katharine was to make this privilege visible. It wasn’t enough to just read the papers; I also needed to read the silences, the absences, the counterfactuals, the might-have-beens. I researched who Katharine didn’t edit, which authors tried to break into The New Yorker but were rejected time and again, including Langston Hughes, Richard Wright, and Alex Haley. I looked at other editors whose careers are not as fulsomely documented, such as Jessie Redmon Fauset at The Crisis. The challenge of twentieth century women’s history is that the archives mirror the circumstances in which they were created, and the researcher needs to imagine what might exist outside them to begin to counteract their biases.

One of the important elements in The World She Edited is the way White nurtured the careers of women writers in her role as editor. Do you have a favorite story about her relationship with one of those writers?

Hard to choose. How Katharine revived Jean Stafford’s career after the end of her violent marriage to Robert Lowell, and eventually introduced her to her third husband, New Yorker reporter A.J. Liebling? How Vladimir Nabokov sent the top-secret manuscript of Lolita to her house only to have her send it back unread?

Perhaps my favorite story is her editing relationship with Mary McCarthy. Katharine loved McCarthy’s writing and worked hard to bring her into the magazine. Their relationship really clicked when McCarthy began writing reminiscences about her ghastly childhood as an orphan of the 1918 epidemic, raised by unbelievably cruel relatives. Katharine worked with her to strike the exact right tone of the stories, which risked seeming too incredible or exaggerated. (Katharine also advanced her money before accepting or publishing these stories, something she often did to nurture writers she wanted to publish—she played the long game.) In one exuberantly grateful letter, McCarthy told her that these edits helped her remember the true events lying underneath her facile prose, that Katharine had magically peered through the manuscript to see the real story, as yet unexpressed. The letters between the two of them are quite touching but also fascinating from a literary critical perspective.

And then I reread the book that McCarthy published from these reminiscences, Memories of a Catholic Girlhood. I had written a chapter of my dissertation on this book, but now, with Katharine’s editing foremost in my mind, I saw it very differently. When she collected the essays, McCarthy did not change a word from how they had appeared in The New Yorker. But after each essay she appended a new passage, usually just a few short pages, which reconsidered the essay, noting what she originally got wrong or misremembered, what she later learned, where she lied or falsified for a good story. She gave a reading of her own work, probing each essay’s weakness and pointing out where it worked. And suddenly I could see that these interludes sound exactly like Katharine’s gentle but substantive editorial memos. McCarthy had been so influenced by Katharine that she adopted this editorial mindset toward her own work, and it struck her as so valuable that she wove it into the structure of her book so that readers could witness this interplay between earlier draft and later consideration. No surprise that Katharine loved the book and its unique design.

What work of women’s history have you read lately that you loved? (Or for that matter, what work of women’s history have you loved in any format?)

What immense pleasure I got from reading The Movement: How Women’s Liberation Transformed America 1963 to 1973 by Clara Bingham. I cannot recommend it highly enough, even to your readers, who are surely more versed than most in second wave feminism. Bingham’s book is an oral history of a tremendously consequential decade, and the dozens of voices we get to hear in these pages make it so lively and vibrant. I guarantee you’ll encounter women and subcultures and victories that you’ve never heard of before. Bingham’s achievement is to render this history fully contingent and suspenseful. You know how it all turns out, of course, but she brings you back to a time when women had far fewer rights and everything to gain by taking risks, speaking out, creating their own networks and institutions from scratch. I found this book equally humbling and inspiring, wildly moving, a page-turner, and above all, deeply relevant.

A question from Amy: How can we use women’s history to forge a path through this post-Dobbs, authoritarian moment, when women, trans people, and LGBTQ folks are highly vulnerable yet ready to fight? What figures and era in women’s history are you reading about to tell us how to counter this administration’s hostility to women?

*Gulp* That is a BIG question. I’m not sure I’m qualified to answer it. (In fact, I urge you to read the Q & A with philosopher and historian Lydia Moland, which will run on March 10, for a much better answer than I can give you.) But here are my thoughts:

First, and most important, find your heroes. Not only women who inspire you with their courage or stubbornness or brains, but women who changed the world to use as your models.Resist efforts to erase women’s accomplishments when you see them. (And they are happening.) If you aren’t able to stop an immediate effort, document it and shout about it where ever you can. And yes, I know this is hard.Keep telling and sharing the stories of women who made changes (especially if they were not given credit for their innovations), women whose stories were covered up, women who fought injustice—you get the idea.Support the people who are telling those stories.If you are in a position to green light projects that tell stories about the history of women or other groups left out of mainstream historical accounts (books, movies, panels, museum exhibits, public programs at a school/church/library), don’t reflexively say no because it might be a hard sell . And don’t cancel scheduled projects just because you are scared. (And yes, that is happening, also.In other words, use women’s history* as a means to speak up and speak out. It would be easy to say that there are more important battles to fight right now. But the politics surrounding who is remembered and who isn’t is powerful and all attacks on liberties are related.

As for me, these Women History Month posts are my own way of speaking up. Or at least one of them.

*And Black history, and LBGTQ history, and Labor history, etc, etc , etc.

***

Interested in learning more about Amy Reading and her work? Check out her website, http://www.amyreading.com/

***

Come back on Monday for three questions and an answer with Sara Catterall, author of Amelia Bloomer: Journalists, Suffragists, Anti-Fashion Icon.

February 24, 2025

Amazons, Abolitionists, and Activists

Amazons, Abolitionists, and Activists: A Graphic History of Women’s Fight for Their Rights, written by Mikki Kendall, author of Hood Feminism, and illustrated by A. D’Amico, is the perfect book to bridge the gap between Black History Month and Women’s History Month.

The book starts with a diverse group of young women discussing the question of who won women’s rights. Their discussion, which is edging toward an argument, is interrupted by the dramatic arrival of a slightly androgynous purple-skinned woman in futuristic attire who announces “This will never do. One question…so many answers.” She then takes them on a tour through “the history you clearly never learned.”

The first two chapters introduce the group of young women, and the reader, to the role of women in antiquity and to a panoply of powerful women from the past, drawn from across the globe. The purple-skinned instructor/tour-guide tells stories that illustrate big ideas, one page at a time. The young women ask questions, squabble among themselves, and have aha moments. Much of this was familiar to me because I’ve spent a lot of time in this world over the last decade or so.* It might be familiar to those of you who have been along for the ride. But my guess is that it is new material for many of the books intended readers, especially in 2019 when the book came out.

Things picked up with the third chapter, titled “Slavery, Colonialism, and Imperialism: The Rights of Women Under Siege.” Our purple-skinned instructor begins with the statement that “Although some queens had to power to change lives, they weren’t always making those changes for the better. And the women their decisions harmed had to find a way to fight back.” For the next five chapters and 130 pages, Amazons, Abolitionists, and Activists tells stories** of women’s fights first for freedom, then the vote, and finally equal rights across time, beginning with Queen Nanny’s leadership of against slavery in Jamaica in the Maroon Wars and ending with the modern world. While the book never uses the phrase intersectional, the stories illustrate the concept clearly. Kendall and D’Amico chose stories about Black, White , Indigenous, and Latinx activists, whose goals are not always the same. They make it clear that white suffragists often were not in favor of Black equality. They introduce us to women who fight for disability rights, labor rights, LBGT rights and environmental rights. They show that sports and the arts are also political forums.

At the end of the book, the group of young women and their instructor end up at place they began, with the question that started them on their journey: Women’s rights: who won them? They now share an answer. Every one has to work for women’s rights. And everyone will have to keep working for them.

Amazons, Abolitionists, an Activists is a good place to begin thinking about the broader issues of civil rights for all. And it is a powerful call to action.

*Hard though it is to believe, I started work on Women Warriors in 2014. Time flies when you’re writing stuff.

**As Kendall and D’Amico make clear, it is never just one story and it is never a single march forward.

February 20, 2025

In which I read How the Word is Passed

I bought Clint Smith’s How the Word is Passed: A Reckoning with the History of Slavery Across America almost as soon as it came out in 2021 after repeatedly hearing what an amazing book it was. But as I mentioned in post earlier this month, I was deep in the world of Nazis and couldn’t face adding America’s history of slavery to the stew in my head. So I put it on the high-priority T0-Be-Read piles that live on my office window sill,* with a promise that I would get to it soon. (Soon is relative in TBR time.)

How the Word is Passed is indeed amazing. Beginning with his home town of New Orleans and ending with discussions with his grandparents, Smith leads the reader on a tour of sites related to the history of slavery and how those sites have been used to tell that story. He does not simply consider the obvious sites.** For instance he looks at historical sites related to the slave trade in New York City—an incisive demonstration of the point that slavery and the slave trade played critical roles in the country as a whole, not just in the south. At each site, he considers not only how the story is told, but who is telling it, who is listening to it, and what stories are being left out. He shares his own reaction to each site, sometimes in physical terms. He makes it clear that slavery, and the long emancipation that followed, have a long tail in this country, emotional as well as economic.

As I read How the Word is Passed, I found myself thinking of Dolly Chugh’s A More Just Future. Chugh discusses how to deal with the discomfort of coming to terms with the disjunction between the history we were taught and the history we we weren’t taught. Smith gives us a personal demonstration of that discomfort. In a discussion of the project as the end of the book, he tells the reader that not only is the book not a definitive account of sites related to slavery, but it is not a definitive account of the sites he chose to visit. Instead, it is “a reflection of my own experience, concerns, and questions at each place at a specific period of time.” Smith’s writing is beautiful, thoughtful and powerful. He kept me turning the pages even when the reading was painful. My heart ached as I read.

If you chose to read one book about Black history this year, How the Word is Passed would be an excellent choice.***

*As opposed to the TBR piles that sit on my office floor waiting for room to open up on the TBR bookshelf, where some books have waited for a long, long time. I will point out that all of the books I am reading for Black History Month are from the high-priority stacks. (I occasionally bemoan the sheer volume of books waiting for me to read them someday, but as I discovered while writing The Dragon From Chicago, books find their time. More than once I discovered I already owned just the book I needed.)

**Monticello, I’m looking at you.

***Personally, I intend to read more over the coming year, though not in such a concentrated way. I will share a list of books from my shelves, read and unread, in my newsletter on February 27. (A good reason to sign up for the newsletter if you don’t get it already. Here’s the link: http://eepurl.com/dIft-b )

February 17, 2025

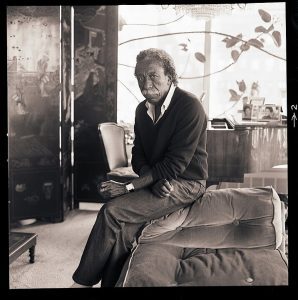

History on Display: Martin, a Ballet Film by Gordon Parks

©David Finn Archive, Department of Image Collections, National Gallery of Art Library, Washington, DC

One of the later chapters of The Swans of Harlem discussed a ballet film by 20th century Renaissance man Gordon Park. Parks is best known for his photojournalism, in which he documented poverty and the civil rights movement from the 1940s through the 1970s, and his groundbreaking blockbuster film, Shaft (1971). He brings those two talents together in the documentary ballet film Martin (1990), a ballet about the life of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.

As a card-carrying ballet fan and history buff, I felt compelled to learn more.

Martin is a ballet with a prologue and five acts corresponding to significant moments in Dr. King’s life: the bus boycott (one of the five Swans of Harlem danced the part of Rosa Parks*), the march on Selma, his time in a Birmingham jail, his assassination, and his funeral. Gordon Parks not only directed and produced the film, but he composed the music.

To my disappointment, I was not able to watch the entire ballet. One full-length copy is available on YouTube, but the copy was so degraded that it was painful to watch. Instead I was able to see three segments: the prologue, Act III and Act V.

In the prologue, Gordon Parks narrates an introduction that deals primarily with the days before and after King’s assassination, played against a powerful montage of Parks’ photographs from the period. Occasionally a very young dancer moves across the screen and then freezes in a pose that resolves into one of the photographs—an enormously powerful technique and one that makes it clear that this ballet was designed for the screen, not the stage. Parks ends with a statement of his intent for the production: “As Martin was committed to a vision, this ballet is committed to the memory of that vision”

I did not find the choreography for Act III, “Letter from Birmingham Jail,” which includes a voice over of the text of the letter, and Act V, Mourning Place, which overtly references the resurrection of Christ from the tomb, particularly compelling, though the dancing itself was excellent. Martin is ultimately interesting as a historical statement, and a historical artifact.

I’m glad I took the time to watch it.

*I’m sure I’m not the only person who wondered whether Gordon Parks was related to Rosa Parks. The answer is no.

February 13, 2025

The Swans of Harlem

As I mentioned in a recent post, I have been fascinated by ballet and its history for most of my life. So when I began to see notices for a book about the forgotten Black ballerinas who danced for the Dance Theatre of Harlem I was eager to get my hands on it. It lived up to my hopes.

Karen Valby’s The Swans of Harlem: Five Black Ballerinas, Fifty Years of Sisterhood and the Reclamation of a Groundbreaking History is more than simple dance history. As its subtitle openly declares, it about how Black women’s stories are doubly erased from history and about the efforts of a group of women “to write themselves back into history.”

The Swans of Harlem begins in 2015, when Misty Copeland became the first Black woman to be promoted to principal dancer at American Ballet Theater. Stories about her undoubted accomplishment ignored those of Black ballerinas before her. Five of those women formed the 152nd Street Black Ballet Legacy Council, named after the home of the Dance Theatre of Harlem (DTH) where they danced fifty years before Copeland,. Their goal was to bring their story back to light; they succeeded with the help of Karen Valby. The extent to which the book is a collaboration between dancers and author is demonstrated by the fact that there are two acknowledgement pages, one for Valby and one for the Swans.

It would have been easy to tell the history of DTH as the creation of one heroic (male) figure, its founder Arthur Mitchell, who was determined to make art in general and ballet in particular accessible to black children—an impulse born from the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. in 1968. And, indeed, Mitchell strides across the pages of the book just as he strode through the lives of the dancers who worked for him—brilliant, beautiful, imperious, obsessed, generous, difficult, and angry. But he is the background against which Valby shares the stories of five important dancers, the paths they took to DTH, their experiences as dancers, their lives after DTH, and the legacies they have created. Their names: Lydia Abarca, Gayle McKinney-Griffith, Sheila Rohan, Marcia Sells, and Karlya Shelton.

The Swans of Harlem is alternatively instructive, heartbreaking, and inspiring. It demonstrates how easily groups of women and people of color are removed from history in favor of stories of individual exceptionalism. Not just for ballet fans. Honest.

February 10, 2025

Shin-Kickers from History: The Griffin Sisters and Vaudeville

In the 1910s, Emma and Mabel Griffin were a well lnown vaudeville act. Performing as the Griffin Sisters, they combined comedy routines with music and dance numbers. (Mabel was the straight woman. Emma got the punchlines.)

They had started working as chorus girls in variety shows in the 1890s. By the beginning of the twentieth century, they were a recognized act on the white vaudeville circuit. They earned good money—sometimes as much as $200 a week.* (Though still not as much as comparable White performers.) But, like other Black performers of the period, Jim Crow laws meant their travel and booking arrangements were often difficult.

In the 1910s, they increasingly performed for Black audiences eager for entertainment. (Performing for Black audiences didn’t lessen the difficulties of traveling in the South.) It was a conscious business decision. They worked to expand Black vaudeville circuits, particularly into the South. In 1913, they founded their own theatrical agency, with the goal of getting Black performers the same terms as their white counterparts. They leased theaters in Chicago and Washington, as the first step in building the Griffin Sisters Vaudeville circuit.

Their plans came to naught. The physical stress of constant traveling caught up with them. In 1913, Emma collapsed on stage. She was hospitalized for more than a month. In 1915, Mabel suffered from a stroke. They continued to perform when they could, but their performances were intermittent. Occasionally one sister had to join forces with another performer when the other could not perform until 1918, when Emma died of bronchitis at the age of 44.

They set the stage, so to speak, for the Black female performers, and theater owners, who followed them.

* Roughly $6000 today.

February 6, 2025

Calling All Citizen Archivists

Depending on where you hang out online or what news media you listen to, you may have heard a call from the National Archives Catalog for volunteers with the “superpower” of reading cursive to join their Citizen Archivist program.* Almost thirty thousand new catalogers signed-up in the week after the call went out—100 times their normal weekly sign-ups according to the folks at the National Archives. That doesn’t mean there isn’t room for more.

Reading handwritten documents from the past can be a challenge.** Signing up to be a Citizen Archivist is simple. No application is required. Just go to the website and follow the instructions to get started.

One of the things I find most appealing about the program are the curated “missions”: sets of documents related to a particular topic that need to be transcribed. The service records of Civil War nurses, for instance.*** Revolutionary War pension files. Or more recently, documents related to the work of the Warren Commission in 1963 and 1964.

It sounds like a wonderful way to dip your toes into the intriguing world of the archives. Future historians will thank you.

*Some of you with sharp memories may feel like you heard this story before. Last year I shared information about a push to transcribe Clara Barton’s papers at the Library of Congress as part of the Library’s By the People public transcription project, By the People. This year, By the People is hosting a transcribe-a-thon dedicated to the writings of Frederick Douglass on February 14, the day on which he chose to celebrate his birth. (Like many enslaved and formerly enslaved people, he did not know the exact date.)

So many ways to help historians of the future work with materials from the past.

**For that matter, reading modern handwritten documents can be a challenge, as anyone who has received a handwritten letter from me can attest. I really try to write legibly, but soon I’m focusing on the idea rather than my handwriting and all is lost. There is a reason I type most of my letters these days.

***It will surprise no one that this particular mission caught my imagination.

****

And speaking of the National Archives, I strongly recommend the organization’s blog: The Unwritten Record. A recent post tells the story of Matthew Henson, a Black explorer who accompanied Robert Peary on multiple expeditions to the Arctic. (Who knew? Not me!) Another is a round-up of links to materials in the archives related to the Six Triple Eight Postal Battalion, the subject of a new movie that I have not yet seen.

February 3, 2025

In Which I enter Black History Month via To Walk About in Freedom

There have been a lot of mixed messages coming from the Federal government about celebrating Black History Month, Women’s History Month, and the like since January 20. Even though President Trump has officially proclaimed February Black History Month, many agencies are canceling events related to theses “cultural celebrations.” (It’s possible this will have all be unwound by the time you read this. Things are moving quickly. )

As far as I’m concerned, February is Black History Month–and it is even more important to recognize than it was before. In honor of Black History Month, I plan to read as many of the books currently in my TBR piles that are related to the topic as I can. As always, I’ll bring you along for the ride.

The Saturday before the Martin Luther King holiday felt like the right time to start. And To Walk About in Freedom turned out to be the perfect first book for the project.

I will admit, I deliberately put off reading To Walk About in Freedom: The Long Emancipation of Priscilla Joyner by Carole Emberton. When it came out in 2022, I was deep into Nazis. I just couldn’t face adding America’s history of slavery and what I learned from Joyner to call the “long emancipation” to the mix in my head. Now I have no excuse. In fact, I feel that it is important at this moment in time to bear witness to a part of our history that we have tried to whitewash from the day of the Emancipation Proclamation onward.

During the Depression, a WPA program called the Federal Writers’ Project sent unemployed journalists, writers and teachers to interview formerly enslaved people as part of a larger program intended to document the lives of ordinary Americans. Priscilla Joyner was the subject of one of those interviews.

Emberton uses Joyner’s story as a structure to explore the collective experience of what she names the “charter generation of freedom,” people who experienced life on both sides of emancipation. She fills out the gaps in Joyner’s interview with information from other oral histories of the charter generation, census data, marriage licenses, and any other relevant document she could find. The result is both a powerful history of the “long emancipation” as it unfolded from the Civil War through the Great Depression and a vivid individual biography. Emberton specifically chose Priscilla Joyner as a subject because much of Joyner’s story was unusual, reminding the reader that Joyner was not simply an exemplar of a generation. In fact, Emberton urges us to remember that the individual stories collected by the Federal Writers’ Project “are not valuable solely because they represent some greater historical truth. Their stories are valuable because they were theirs, and because they chose to tell them, imperfectly, to an unlikely army of public historians thrown together in the midst of a global economic crisis by a government that had shown very little concern for the fate of ex-slaves since Reconstruction.”

In her final chapter, titled “The Book,” Emberton traces the use and abuse of the WPA interviews of formerly enslaved people by white historians who were determined to present a positive image of the treatment of enslaved people by their owners. It is a salutary reminder that history is written by people, and some of whom are willing to twist sources to support their own agendas. (And none of us are entirely objective.)

I strongly recommend To Walk About in Freedom. I found it to be an engaging read and a master class in re-examining sources to support a broader story.

My Black History Month reading is off to a good start!

January 30, 2025

Cecilia Payne Finds Out What Stars are Made Of

One or twice a year, the story of English-born astrophysicist Cecilia Payne (1900-1979) appears on my Facebook feed. I am enthralle– and enraged–by the story every time. And then I promptly forget her name. A fact that is both frustrating and somewhat embarrassing since this is the kind of story that I firmly believe needs to be known more widely. I hope that by sharing her story with you I can not only spread her story a little further, but anchor it firmly in my brain.

When Cecilia Payne entered Cambridge University in 1919, she knew she wanted to study a science, but did not yet know which one. That changed when she heard a lecture by astronomer Arthur Eddington. Stars were her future.

She quickly realized that she could not have a professional career in astronomy in England. She couldn’t even get a doctorate. In 1923, she came to the United States where she became a graduate fellow at the Harvard College Observatory, which was involved in a long study of the patterns of light emitted by stars, technically known as stellar spectra.* One of the goals of this study was to understand what elements the stars were made of by comparing their spectral lines with those of known chemical elements. Astronomers had already identified heavy elements such as calcium and iron and assumed they were major components of the stars.

Payne applied principles from the new science of quantum physics, which she had studied at Cambridge, to the study of stellar spectra. In her doctoral thesis, the first awarded for work at the Harvard Observatory, she demonstrated that the sun and other stars were composed almost entirely of hydrogen and helium, the two lightest elements—a discovery that overturned previous assumptions. She added a butt-covering caveat to her thesis stating that the abundance of of hydrogen and helium were “almost certainly not real.” She was, after all, a 25-year-old woman in a field in which most women doing scientific work were described as “computers” not scientists.

Like many newly minted PhDs, Payne revised her thesis and published it as a book. Stellar Atmospheres was well receive. It was soon accepted that her results were in fact quite real, and that they profoundly changed what we know about the universe. In 1960, astronomer Otto Struve, no slouch himself in the study of stellar spectra and a founder of radio astronomy, referred to her work as “the most brilliant PhD thesis ever written in astronomy.”

Payne worked at the Harvard Observatory for many years, doing the work of a faculty member with the lower-paid and less-respected title of “technical assistant” to Harlow Shapley, the Observatory’s director. During this period, she published several important books based on her research. In 1956, she was finally made a full professor—the first woman to hold that title at Harvard—and chair of the Astronomy Department.

In 1976, the American Astronomical Society recognized her work as one of the most creative astronomers of the twentieth century, with the Henry Norris Russel Lectureship, which honors a lifetime of excellence in astronomical research.

*It should be pointed out that a group of 80 women did much of the laboratory work related to this project. Hired as “computers” and often ridiculed as “Pickering’s harem,” they literally mapped the heavens. Among other things, they catalogued which stars could be photographed by attaching a spectroscope to a telescope, which records the range (spectrum) of colors which make up starlight. (This is very simplified and possibly even inaccurate.) Once pictures were taken, they classified the spectra displayed in the photographs. They were paid 25 to 35 cents an hour, less that they would have made at a clerical job, and worked six days a week, seven hours a day.

Dava Sobel’s book about this, The Glass Universe, is now high on my TBR list.

Some of the women of the Harvard Observatory, ca. 1910, with the man who hired them, Edward Pickering.

Annie Jump Cannon, one of the women employed by the observatory, had already created a classification system that sorted the spectra of several hundred thousand stars into seven groups based on differences in the spectral features before Payne arrived.** Her system is still in use today.

**In other words, Payne’s work depended on the scientific work of another unheralded woman. Cannon was finally given the title of Curator of Astronomical Photographs.

January 27, 2025

The Pragmatic Sanction of 1713–aka as Girls Can Rule, Too

Back in December, when I was trying to make sense of the tangled succession of the Hapsburg dynasty and Holy Roman Empire, I came across a reference to the Pragmatic Sanction, issued by Emperor Charles VI in 1713. It caught my attention for reasons that will become clear to you in just a moment.

Charles VI, ca 1720/1730

In European political history, the term “pragmatic sanction” refers to a princely decree that deals in a pragmatic way with a situation that cannot be solved by applying the usual rules. The term “the Pragmatic Sanction,” with capital letters and no qualifiers, always refers to the decree issued on April 19, 1713 by the Emperor Charles VI, head of the Hapsburg house, ruler of Austria and all its possessions, and Holy Roman Emperor. The purpose of the edict was to ensure that one of his daughters could inherit the Hapsburg lands, undivided.

Pragmatic is the key word. Charles had no interest in expanding women’s rights.* His only concern was protecting the Austrian succession. At the time that he issued the edict, Charles was the only surviving male member of the House of Hapsburg. Salic law, which previously controlled the Hapsburg succession, precluded inheritance through the female line.** The failure of the male line could lead to a succession dispute and the and the potential dismemberment of the Austrian empire. (The title of Holy Roman Emperor was not part of the discussion because it was an elected office that did not automatically go with the Hapsburg heir.)

The Hapsburgs had already made an attempt to circumvent Salic law during the rule of Charles’ father, Emperor Leopold (1640-1705). In 1703, neither Charles nor his older brother Joseph had sons. The family made an agreement regarding the succession that allowed the throne to pass through the female line if all male lines had become extinct.*** In practical terms, this meant that if Joseph, who had two daughters at the time, died without sons he would be succeeded by Charles. If Charles, in turn, died without a son, Joseph’s oldest surviving daughter would become the ruler of Hapsburg Austria.

Joseph succeeded his father in 1705. Charles succeeded Joseph in 1711, with his niece, Maria Josepha, as his presumptive heir. Two years later, Charles announced the Pragmatic Sanction, which privileged his own daughters over those of Joseph.****

At the time it was an entirely theoretical amendment because Charles and his wife, Elsbeth Christina of Brunswick-Wolfenbütel, had no children. That soon changed. In 1716, the couple had a son, who died a few months later. Three daughters followed: Maria Theresa, in 1717, Maria Anna in 1718, and Maria Amalia in 1724.

Maria Theresa, ca 1730 –not yet the empress

In 1740, Charles VI was succeeded by his daughter, Maria Theresa, who was then 23. Despite the edict, and the carefully negotiated agreements to it, Charles Albert of Bavaria and Frederick the Great of Prussia immediately contested her succession. The War of the Austrian Succession cost Maria Theresa part of her land, but not her throne. She ruled for forty years until her death in 1780. Just to keep things tidy, her husband Francis I was elected Holy Roman Emperor.

***

A couple of personal tidbits about the Empress Maria Theresa, who was possibly the most powerful of the Hapsburg rulers of Austria:

She married for love, not for political power. Her husband, Francis Stephen, was a prince of Lorraine in France—a minor principality by any standard and certainly less powerful than the Hapsburg Empire. Like England’s Queen Victoria, she wore mourning for the rest of her life after his death in 1765.She was pregnant at her coronation. She would go on to have sixteen children, the best known of which was the future queen of France, Marie Antoinette.I have no doubt that we’ll be coming back to her in the future. She is too important and I know so little about her.

*Though it is worth pointing out that the Hapsburgs had already embraced the concept of female rulers on a smaller scale. They regularly appointed unmarried women of their royal house as regents over provinces in their widespread empire. Charles VI appointed his sister, the Archduchess Maria Elisabeth, as regent over the Austrian Netherlands in 1724, a position she held until her death in 1741. (It does make me wonder why Leopold’s original end-run on Salic Law did not name Maria Elisabeth as Charles’s successor ahead of her nieces.)

**Just so you don’t have to look it up: the Salic Law was a medieval law code which was originally issued by Clovis, the first Frankish king, in the fifth century and became the foundation for law in French and German principalities well into the Napoleonic period. One of its most influential clauses, which stated that daughters could not inherit land, was used to prevent women, or anyone descended from a previous ruler through a woman, from succeeding to the throne. After all, if Maria couldn’t inherit her father’s farm, why should the Archduchess Maria be able to inherit her father’s kingdom?

***Extinct appears to be the technical legal term for this, but it always makes me think of dinosaurs.

****Just because Charles announced the change didn’t mean it happened with no political wrangling. Even an emperor couldn’t enforce an edict about his succession without other people on board. In the case of the Pragmatic Sanction, Charles VI had to convince 1) his nieces and their future spouses 2) the various diets and parliaments of the affected Hapsburg lands and 3) the great powers of Europe. It was 1725 before all the affected parties agreed.