Pamela D. Toler's Blog, page 11

January 23, 2025

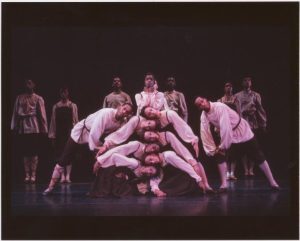

Bronislava Nijinska, of the Ballets Russes and Other Dance Companies

I became fascinated by Serge Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes in my senior year in college thanks to a class run by the music department.* I had already been familiar with some of the music, and a few of the names. That class introduced me to the company as a convergence of modernisms in the hands of great artists, including designer Léon Bakst, poet and filmmaker Jean Cocteau, Pablo Picasso (!), composers Erik Satie and Igor Stravinsky, dancer and choreographer Vaslav Nijinsky, and Diaghilev himself, who elevated the role of impresario to an art form in itself. One artist was left out of the line-up: Nijinski’s sister, Bronislava Nijinska, who was also a dancer with the company and an important choreographer in her own right.

It was another decade or more before I heard the name Bronislava Nijinska. Nijinska studied ballet in Saint Petersburg alongside her brother. Like her brother, she was a dancer in the Ballet Russe and she created a number of roles in ballets for the company. She choreographed several important works for the Ballets Russes, including Le Spectre de la Rose (featuring her brother), Les Noces (“The Wedding”) and Les Biches (literally “The Does”, also known as “The House Party”). (All of which we had studied in that college course, with no mention of the choreographer, though we did discuss Nijinski’s role in Le Spectre de la Rose.)

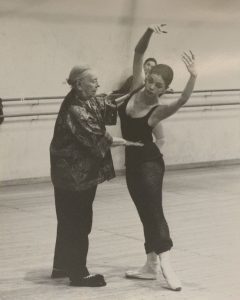

Nijinska in rehearsal, ca 1933

In 1925, she formed her own company, Théâtre Chorégraphic. She also created more than 60 ballets, not only for her own company but on commission for a number of other prominent dance companies of the period, including Anna Pavlova’s company. In 1938, she moved to Los Angeles, where she opened a school. She continued to work as a guest choreographer almost until her death in 1972.

Nijinska in rehearsal, 1968

Her works were experimental in form, and occasionally shocking in theme. (Les Biches explicitly explores the sexual mores of the 1920s.) She used, and expanded, modernist elements in dance, such as rhythmic complexity, innovative movements outside the vocabulary of classical ballet, and increasing abstraction.

She was never forgotten. But Nijinska’s long, productive career has been consistently overshadowed by that of her brother, who succumbed to mental illness at 29 and created only four ballets, including the astonishing The Rite of Spring, in which Nijinska danced the central role. In part, she was relegated to the shadows because only three of her works survive in full—a result of the fact the companies she worked for did not last so her works fell out of the dance repertory. The only work that has consistently been revived is Les Noces, despite his large cast (forty dancers) challenging style, and complex Stravinsky score.

But perhaps the style of her work has also played a role. She used the female body in unconventional ways, both as a choreographer and as a dancer. Strong unconventional female voice consigned in the corners of history–who would have thought?

* Ballet caught my imagination long before I became a history bugg. One of my earliest memories is seeing a a dancer on television and knowing that was something I wanted to do.* I started taking lessons as soon as I was old enough, and because I was a budding history bugg I also started reading about the great dancers of the past. My interest in dance history continued long after an in-class accident ended my ability to continue with ballet.

January 20, 2025

From the Archives: Industrial Espionage

Reading Sarah Rose’s account of how British botanist Robert Fortune smuggled tea plants, and tea workers, out of China in the nineteenth century, made me think about another case of materials smuggled to end a Chinese monopoly. This first ran in 2012.

©Trustees of the British Museum

The Chinese produced luxury silk fabrics for several thousand years before they began trading with the west. Scraps of dyed silk gauze found in a neolithic site in Zhejiang Province date from 3600 BCE. Silk fabrics woven in complex patterns were produced in the same region by 2600 BCE. By the time of the Zhou dynasty, which controlled China from the twelfth to the third centuries BCE, silk was an established industry in China.

Wild silk, spun from the short broken fibers found in the cocoons of already-emerged silk moths, was produced throughout Asia. Only the Chinese knew how to domesticate the silk moth, bombyx mori, and turn its long fibers into into thread. They kept close control over the secrets of how to raise the domestic silkworm and create silk from the long fibers in its cocoon. Exporting silkworms, silkworm eggs or mulberry seeds was punishable by death. It was more profitable to export the finished product than the means of production.

The Chinese monopoly on the secrets of silk production and manufacture was eventually broken. According to one story, a Chinese princess, sent to marry a Central Asian king, smuggled out what silk cultivators called the “little treasures” as an unofficial dowry. (In one cringe-inducing version of this story, the princess carried the silkworms in her chignon to escape detection at the border.* It was illegal for a commoner, like a border security agent, to touch the head of a member of the royal family.) A totally different tradition tells of two Nestorian monks who smuggled silkworm eggs out of China in hollow staffs and carried them all the way to Byzantium, traveling in winter so the eggs wouldn’t hatch.

However the “little treasures” traveled, the Chinese monopoly on silk production was over by the sixth century CE, when the Middle Eastern cities of Damascus, Beirut, Aleppo, Tyre, and Sidon became famous for their silks.

* Would you want these in your hair? Makes your scalp crawl doesn’t it?

* Would you want these in your hair? Makes your scalp crawl doesn’t it?

January 16, 2025

For All the Tea in China

A decade or more ago, I picked up For All the Tea in China: How England Stole the World’s Favorite Drink and Changed History by Sarah Rose from the free box that used to sit outside a used bookstore down the street from my office.* And then it sat on my shelf, unread.

I will admit, it made its way to the top of the to-be-read pile recently because I was doing a lot of traveling and wanted something that was physically light but had some mental heft to read in route. It turned out to be a very good choice for many reasons, including the fact that the heart of the book was about one man’s travels through China in the 19th century. His travails made the annoyances of modern air travel look small indeed.

For All the Tea in China is the story of how the British East India Company sent botanist Robert Fortune to China in 1848 with the mission of acquiring tea plants and smuggling them out of the country. Their goal was to establish tea plantations in the Himalayas, allowing them to circumvent China, which was then tea purveyor to the world. In 1851, he made a second trip—this time to acquire tea experts to teach Indians how to properly grow and process the plants he had acquired. (Getting them out of the country was just as illegal as smuggling the plants themselves.)

Rose tells the basic story as an adventure, with overtones of the imperialist adventure stories I happily read as a child,** complete with disguises, untrustworthy local employees, pirates, and territorial East India Company agents. She uses that story as a framework for discussing the role of botany in general and tea in particualar in the growth of the British Empire, the details of tea production, and the tea trade in Britain. She makes interesting side trips into subjects like Linnaeus’s classification system,*** Wardian cases (what we known as terrariums), and ship building.

Well worth the read, with or without a mug of tea at hand.

*That box was a treasure trove. For years I checked it almost every day and scored some wonderful things, including a 1913 edition of the unabridged Funk & Wagnalls that holds a place of honor in my study.

**Oh all right, I still read them on occasion. But now I am aware of the problematic elements that escaped me when I first discovered them.

***Which led me into a side trip of my own as I realized that I had put Carl Linneaus in the wrong century in my mental chronology of the world.

January 14, 2025

Happy birthday, Sigrid Schultz!

Sigrid Schultz was born on January 15, 1893, shortly before the world’s fair known as the World’s Columbian Exposition.

Sigrid spent her early childhood in an area with the evocative name of Summerdale, now part of the Edgewater neighborhood on Chicago’s North Side. The neighborhood, located within the Chicago city limits, was largely undeveloped. There were four houses on the block where the Schultz home stood. Native prairie, rich with prairie hens, pheasants, quail and a riot of bright wild flowers, ran alongside the fenced-in gardens, creating a wild playground where Sigrid roamed in the company of three boys from the house closest to the Schultz home, protected by the family’s St. Bernard, Barry, who had served as her “nanny” since she was a baby.

The idyllic Chicago childhood of Sigrid’s memory came to an end in 1901, when Sigrid was eight. Her father moved her family to Europe following an important portrait commission. He intended to stay in Europe for two years. It would be 1941 before Sigrid would once again live in the United States, but she always thought of Chicago as home.

And there is no doubt that she learned things during her years in Chicago that laid the groundwork for her later career as the Berlin bureau chief for the Chicago Tribune: the importance of language, the power of hospitality, and the necessity of standing up against bullies and prejudice.

Happy birthday, Sigrid!

January 9, 2025

Portrait of a Woman: Art, Rivalry and Revolution in the Life of Adélaïde Labille-Guiard

Bridget Quinn first introduced readers to the eighteenth century French painter Adélaïde Labille-Guiard in Broad Strokes, her rollicking account of fifteen women artists “who made art and made history (in that order).”* In Portrait of a Woman: Art, Rivalry and Revolution in the Life of Adélaïde Labille-Guiard, Quinn returns to her subject in a work that is equal parts biography, historiography, and memoir. She traces not only Adélaïde’s life,** but the artist’s role in Quinn’s own life as art historian and author. She introduces the reader to the broader context of art and artists in pre-revolutionary France and the restrictions on women artists within that context. She examines Adélaïde’s artistic rivalry with the better known artist Élisabeth Vigée-Lebrun, which was in some ways constructed as a result of those restrictions. She follows Adélaïde’s attempts to navigate the French art world, the royal system of patronage, and the dangers of the French revolution—and her support of other women artists. Along the way, she makes Adélaïde’s mastery as a painter clear for the modern reader/viewer.

Personally, I have every intention of visiting the masterpiece that hangs in the Met on my next visit to New York thanks to Bridget Quinn.

If you are interest in art, women’s history, or the places where they overlap, this one’s for you.

*I just noticed the double meaning of “Broad” in the title. *Duh*

** See my interview with Quinn in my series of interviews for Women’s History Month in 1922*** for her discussion of using first names for women artists. Her article on the subject triggered my own fascination with the subject.

***I’m running the series again this March, featuring some good people doing a wide range of work.

January 6, 2025

Women in the Valley of the Kings

One of my favorite books as a child was C.W. Ceram’s Gods’ Graves and Scholars. His aim, described in his foreword, was “to portray the dramatic qualities of archaeology, its human side.” And at some level he succeeded admirably. Ceram is largely responsible for my lifelong fascination with archaeology. It was only when Kathleen Sheppard’s Women in the Valley of the Kings landed on my desk that I realized just how narrow his definition of “human” was.

Subtitled The Untold Story of Women Egyptologists in the Gilded Age, Sheppard’s book tells the stories of women who worked in the field at the same time as, and sometimes alongside, well-known pioneers of Egyptology like Flinders Petrie and Howard Carter. I will admit, this book would not have hooked 8-year-old Pamela the way Ceram’s did. There is less adventure and more of what Ceram describes as “bookish toil.”* Sheppard’s archaeologists fight not only the hardships of working in the desert, but social expectations about what women could/should do. While some of them did discover important sites and artifacts, much of their most important work happened off-site. where they built and maintained the infrastructure that made the study of ancient Egypt possible. As Sheppard sums it up, “…women recorded, organized, catalogued, and corresponded. Men got dirty, had adventures, and excavated artifacts. Women, in fact, founded the institutions that would received these artifacts and allow the rest of the world to see them.” No less important, but definitely less flashy.

*Sheppard also acknowledges the inherent role of colonialism in the development of Egyptology, something missing from Ceram’s account, which was originally published in 1943.

January 3, 2025

What’s Up for 2025?

It’s a tradition here on the Margins that I use my first post of the year to share the historical topics that I plan on spending time with in the coming year. It’s a way to put my thoughts in order. A little self-indulgent perhaps, but I hope some of you find it enticing. Maybe even thought-provoking.

My first answer when I asked myself what I’d be working on in 2025 was “I have no flipping idea.” But in fact that isn’t true. The Dragon From Chicago will continue to take up a good deal of my time, energy, and enthusiasm. (And rightly so.) I already have speaking gigs, virtual and in real life, lined up well into the year, and I am hoping for more.*

But, much as I love talking about Sigrid Schultz, I need to re-fill the well. Here are some other historical topics that I expect to be thinking, reading, and writing about this year:

1. Women’s history in general. I have a big pile of unread books to work my way through during this period when I am relatively deadline free.** And a list of more books that I plan to add to the pile as soon as I get to my neighborhood bookstore. (My Own True Love gave me a nice gift card for Christmas and I am eager to use it.)

2. Women cartoonists and illustrators in general. (The Queens of Animation made me curious.***)

3. Ancient Egypt: an old passion with a new impetus. I’m taking a trip down the Nile with my BFF from graduate school. So. Dang. Excited.

4. Plane-spotting in World War II, and some other aviation topics.

If I’m lucky, something totally unexpected will catch my imagination and send me on a detour. I love a good detour. And I love taking you on the trip with me.

Here’s to a New Year filled with health, happiness, and history-nerdery for us all.

*And speaking of speaking, if you belong to a group that needs speakers, send me an email and we’ll try to work it out. Zoom has made things possible that were not possible before. If you want to know where I’ll be or find links to podcasts I’ve been on, the newsletter is the most reliable place to check . I am ashamed to admit that I have fallen behind on updating the events page on my website. And until I started typing this I had forgotten about the events page on this blog altogether. (Moving updates up the to-do list as I speak. So to speak.)

**Except for blog posts, and newsletters, and prepping for speaking gigs, and… Well, you get the idea. There is always something in the pipeline.

***This is how it starts.

December 23, 2024

Home for Christmas

By the time you read this, My Own True Love and I will be in the Missouri Ozarks, celebrating the holiday with my family. Unlike many families, whose Christmas traditions are carved in stone, my family’s traditions have always been fluid, re-created from year to year to reflect new discoveries/ enthusiasms/family members/challenges. This year will be no exception. (One tradition I am pleased to abandon this year is my annual holiday respiratory infection. No sign of it yet.)

Our Christmas is always different, and always fundamentally the same. I am looking forward to it.

As I have for the last few years, I’m giving myself a holiday from blogging—a tradition that seems to have legs,* unlike, say, the kazoo band my parents engineered one year. I’ll be back in January with some historical stories you probably haven’t heard and some books you might enjoy.

In the meantime, have a merry/jolly/happy/blessed time as you celebrate the victory of light over the darkness in the tradition of your choice.

*At least for the moment

December 20, 2024

1924: A (Really Long) Year in Review

This was the year that inspired me to return to writing “A Year in Review” posts. Things related to 1924 caught my attention over the course of the year. Not just events related to Sigrid Schultz and Nazi Germany, though obviously that was part of it. The more notes I took about 1924, the more items I saw: Blue Ford Syndrome at work once more.

When I finally sat down to write this post earlier this week, it spun totally out of control. So many events, so many possible themes, so much STUFF. In fact, that out-of-control feeling could be a metaphor for 1924 as a whole. The Roaring Twenties were in mid-roar.* It was a period of creativity, heavy drinking,** and social disruption. As Sigrid Schultz described it, the mid-1920s were a time when “people were still living at top speed trying to catch up with the fun they had missed in wartime and fun they might miss in the upheaval that was bound to come.” Sometimes the speed was literal: more and more people owned automobiles and aviation advances made the front page on a regular basis.

It was also a period of political disruption as Europe, Russia, and the former Ottoman Empire attempted to settle into the changes wrought by revolutions and the terms of the Versailles Treaty.

But let’s look at 1924 specifically.

In the arts, just to name a few of the many possible choices:

George Gershwin premiered his Rhapsody in Blue, which combined jazz elements with classical composition in new ways and has been the subject of conversation and controversy ever since.***

Thomas Mann published The Magic Mountain.

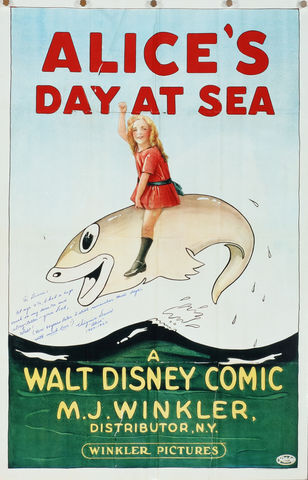

Walt Disney released the first cartoon from his own studio, a short titled Alice’s Day at Sea that combined live action shots of a young actress and a big dog with animated characters and background.

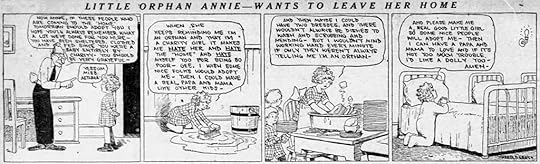

The first Little Orphan Annie cartoon strip

The comic strip Little Orphan Annie, created by Harold Gray and syndicated by the Chicago Tribune’s Tribune Media Services, debuted in the New York Daily News on August 5. It quickly became one of the most popular strips in syndication, running from 1924 to 2010. In 1930, its eponymous heroine also became the subject of a highly-rated radio program that ran for twelve years.

French poet André Breton published the First Surrealist Manifesto, which is considered one of the most important texts of modern art, on October 15. (Personally, I think Little Orphan Annie left a bigger cultural footprint in the world’s imagination.)

In science and industry, loosely defined:

Astronomer Edwin Hubbble announced his discovery of the spiral nebula Andromeda (now called the Andromeda galaxy) in an article in the New York Times, proving the existence of other galaxies for the first time. He went on to create the most commonly used system for classifying galaxies. There’s a reason they named the big space telescope after him.

Engineer Carl Taylor patented an machine that rolled freshly baked thin wafers into ice cream cones—a small step for man, a giant step for mankind. His machine built on the innovation of a Syrian-American chef named Ernest Hamwi, who rolled zalabia, a waffle like pastry, into cones at the St. Louis World’s Fair in 1904, when ice cream vendors at a neighboring stand ran out of serving bowls. (Or so the story goes. There are lots of competing claims about who created the first waffle cones. Hamwi, however held the patent for a cone maker which Taylor’s machine was designed to work with.)

Depending on who you listen to and how you define terms, the first radio broadcasts aimed at a listening public happened in 1916, 1920, or 1921. No matter which version you accept, radio was still new in 1924 but it was making an impact. Here are a few radio firsts from 1924

The Republican presidential convention was broadcast live to nine cities from the public auditorium in Cleveland, Ohio. Calvin Coolidge was the nominee.After the election, Calvin Coolidge was the first president to deliver a radio broadcast from the White House. He had appeared on radio for the first time the year before. Four months after he became president following Warren G. Harding’s death, he chose to broadcast his Annual Message (what we now call the State of the Union address) from the House of Representatives. Coolidge was not a radio fan, but he understood the value of the medium, which allowed him to enter the homes of millions of Americans without leaving Washington.The Royal Greenwich Observatory began broadcasting hourly time signals.The first photo facsimile was transmitted across the Atlantic by radio from London to New York City, which meant that newspapers could now run photographs from overseas while they were still news. (Do not ask me how this works.)Ford produced its 10-millionth Model T. (See, I told you there were more cars on the road!) The company sent it on a cross-country tour on the Lincoln Highway from New York to San Francisco. Excited crowds gathered along the way to cheer it on as if it were a visiting dignitary, which in some ways it was. (Please remember, if you want to watch the video, you need to open the post in your browser. You can do this by clicking the post title.)

In related news, Rand McNally published its first road atlas, called the Rand McNally Auto Chum.

In Europe, the political repercussions of the Great War were still shaking out. Here are a few examples, in roughly chronological order:

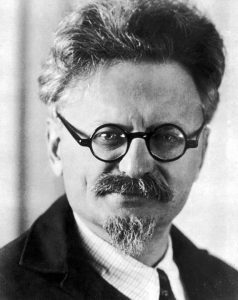

Vladimir Lenin died in January. A few day’s after Lenin’s death, the city of Petrograd was renamed Leningrad. Millions of mourners from across Soviet Russia waited in line for hours to see his body, which was embalmed and placed in a mausoleum in Red Square. His death provoked a power struggle in the newly formed USSR that was not resolved until the late 1920s with Trotsky’s exile and the subsequent consolidation of power in Stalin’s hands. (And yes, the Soviet Union had its roots in Russia’s disastrous experiences in World War I. )

In related news, several newly formed states were absorbed into the Soviet Union, in theory as independent states. They were not necessarily happy about their new circumstances. In fact, nationalists in Stalin’s home state of Georgia staged an unsuccessful uprising against Soviet rule, known as the August Uprising.

The Treaty of Versailles created new states, and new border disputes. One of the oddest of these was the short-lived Free State of Fiume,which was dismantled in January, 1924 in the Treaty of Rome. The Kingdom of Italy annexed the Free State of Fiume and the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes absorbed Sušak. Similarly, Lithuania took the Klaipeda region from East Prussia, making it an autonomous region under Lithuanian sovereignty, though not for long.

The Turkish Caliphate, which was the final remnant of the Ottoman Empire, which had been abolished after the Great War, was abolished on March 3, bringing the Caliphate to an end. All members of the Ottoman dynasty were exiled. The constitution of the new Republic of Turkey was adopted on April 20. The new state had a secular government. On the downside, Kurdish schools, publications, and associations were banned.

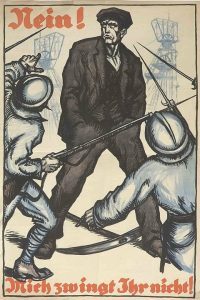

Germans engaged in passive resistance against French and Belgian occupation of the Ruhr

German reparations were a constant issue from the moment the Versailles Treaty was signed to the Adolph Hitler’s ascension to power in 1933. Germans believed that the reparations were unfair and a major cause for the country’s economic problems. The allied states disagreed. When Germany defaulted on a payment in January, 1923, France and Belgium occupied the Ruhr district of Germany in an effort to force Germany to pay up. (It didn’t work, but that’s a story for another day.) In April 1924, the German Reichstag approved the Dawes Plan, created by an international committee headed by American banker Charles G. Dawes. The plan was intended to resolve disputes over German reparations.It provided for the end of the French and Belgian occupation of the Germany’s Ruhr region.. It put the German economy under international supervision and created a payment plan for Germany, which lowered Germany’s annual reparations payment but left the full amount to be paid uncertain. In the short run, the plan stabilized the German economy, which was suffering from hyperinflation, but it did nothing to resolve the fundamental conflicts related to reparations. Many French citizens believed their government was being too lenient to Germany. Many Germany citizens believed the entire world was dog-piling on Germany. Dawes, who was vice-president under Calvin Coolidge, received the Nobel Peace Prize in 1925 for his work on the plan.

The Dawes committee in Berlin

And speaking of fundamental conflicts between Germany and the allied powers, at the same time that Europe was trying to put World War I to bed, it was also taking steps toward World War II:

The French government signed a treaty of mutual aid with Czechoslovakia in light of the possibility of an unprovoked attack by a third country. It turned out not to be worth the paper it was written on. At the Munich Conference in 1938, instead of defending Czechoslovakia, France and England compelled Czechoslovakia to surrender the Sudetenland region to Germany without putting up a fight.

Adolph Hitler was sentenced to five years in prison for his participation in the 1923 Beer Hall Putsch. The coup failed, but from Hitler’s perspective it could be considered a success. The trial gave him more public attention than he had enjoyed before, and he made the most of it. At every chance during the trial, he gave speeches declaiming what would become major Nazi positions. He served less than nine months of his sentence, and used the time to write Mein Kampf.

The Fascists won the general elections in Italy with a two-thirds majority. Several months later, the fascists’ leader, Benito Mussolini, ordered the suppression of opposition newspapers. (A few months later, he expelled Chicago Tribune reporter George Seldes for what Seldes described as “honest reporting.”)

In Japan, things were literally shaking:

A major earthquake caused the Great Fire of Tokyo, killing 143,000. To put this in context: The Great Chicago Fire LINK of 1871, which was NOT caused by Mrs. O’Leary’s cow, killed 300 and left 100,000 homeless. Accounts of the casualties in the San Francisco fire of 1906, also caused by an earthquake, range from 700 to 3000.

In the United States,****

Congress passed a new immigration law. In addition to limiting the total number of immigrants allowed into the country each year, the new law established immigration quotas for each country based on the proportion of each nationality in the United States in the 1890 census, effectively reducing immigration from central and southern Europe. Asian immigrants were excluded altogether, with these exception of those from Japan and the Philippines. (These exceptions were the result of political pragmatism. Japan kept tight control over the number of immigrants allowed to leave. The Philippines was a U.S. Possession.) The quotas remained in place, largely unchanged, until 1965.

A month later, Coolidge signed the Indian Citizenship Act, which declared all Native Americans to be American citizens.

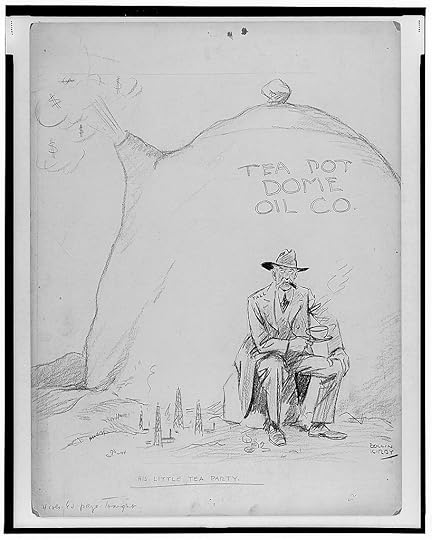

Edwin Denby, U.S. Secretary of the Navy, and Albert B Fall, Secretary of the Interior, were forced to resign as a result of the Teapot Dome Scandal over government corruption regarding oil leases.

J. Edgar Hoover was appointed director of what was then called the Bureau of Investigations, a position he would hold for 48 years.

Nathan Leopold and Richard Loeb abducted 14-year-old Bobby Franks and murdered him. Both Leopold and Loeb were wealthy and intelligent. Their sole motive was to commit a perfect murder. They did not succeed. Their trial became a national sensation.

Nellie Tayloe Ross of Wyoming (1876-1977) was elected as the first woman governor in the Unites States, filling her husband’s unexpired term after his death. (Another example of what political scientists often term the “widow’s walk to power.”) After being defeated for reelection in 1926, she went on to become the vice chair of the Democratic National Committee. President Roosevelt appointed her to two five-year terms as Director of the U.S. Mint. (Why don’t we ever hear about these women??!! )

A couple of nice things to cleanse our historical palates:

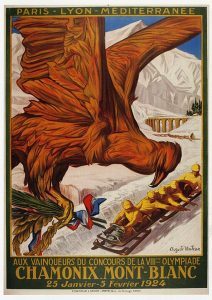

The first Winter Olympics was held at Chamonix in the French Alps: eight sports, 16 events, 293 participants, 16 nations

The first Negro League World Series took place, attracting interest from baseball fans who had not shown interest in the Negro Leagues before.

*If the Oxford English Dictionary is to be believed, the term was in use as early as 1923—apparently people realized even then that the times were roaring. (Interestingly, the term was applied to the 1820s as the nineteenth century drew to a close. Who knew?) Germans call the same period the “Golden Twenties,” which has an entirely different feel.

**Not just thanks to Prohibition, though it certainly played its part.

***I first heard it when I was twelve and it remains one of my favorite pieces of music. Its opening bars are engraved in my brain and make my heart swell every time I hear them.

****I am aware that things happened in the Americas in 1924 outside the United States, but I must admit I don’t know enough to prioritize what is important and what isn’t. Embarrassing, but true. I’m also leaving out China, where the Nationalist and Communist parties were active, and India, where the nationalist movement was gaining ground. And in the case of India, I don’t have the excuse of not knowing enough.

December 16, 2024

What’s her Name: A History of the World in 80 Lost Women

What’s Her Name: A History of the World in 80 Lost Women is exactly the book I would have expected from the creators of the popular . Olivia Meikle and Katie Nelson not only tell the stories of forgotten women with their trademark combination of wit, enthusiasm and rock-solid research, they use those stories as a lens to re-examine world history as it is usually taught, and re-create it in the process

At first glance, the structure of the book will look familiar to anyone who took World History in an American high school: the stone age, first civilizations, ancient empires, the Middle Ages, etc etc etc., ending with the atomic age. The story told within those chapters takes that structure, spins it around, holds it upside down and shake it until things fall out of its pockets. The result is dizzying, and enlightening. Olivia and Katie re-examine familiar stories from a new perspective. (I’ll never look at the Venus of Willendorf the same way again. And I refuse to say more because —spoilers.) They introduce us to women who don’t make it into standard world history texts, despite playing important roles in the big picture.* (The Trung sisters of Vietnam, for instance.) They tell us the stories of women who made discoveries, who stood up in resistance, and who simply led their lives in ways that tell us more about their time and place. In the process, they question some of the truths about history that have seemed self-evident, and find slightly different answers. Bigger answers.

What’s Her Name is funny, subversive (in the best possible way), and very, very smart. To quote one of my favorite lines in the book, it is a history of the world with “Less patriarchy, more elephants.”

*Though they are beginning to make their way into books written for a popular audience, like my own Women Warriors—a fact that Olivia and Katie acknowledge with thanks on the first page of the book.