Pamela D. Toler's Blog, page 12

December 12, 2024

1824: A Year in Review

Once I learned this was also a leap year, it took only the briefest trip down the rabbit hole to learn that all the years ending in 24 are leap years. Because, math.

Empires expand and contract

Battle of Rangoon, May 1824

The First Anglo-Burmese War (known as the First British Invasion in Burmese accounts*) broke out in March, following the Burmese occupation of Assam and Manipur. The war lasted for two years, ending in a decisive, but expensive victory for the British. The British gained control over the northeastern section of the Indian subcontinent. In addition to territory, the Burmese signed a commercial treaty with the British East India Company.** It was the beginning of the end for the powerful Burmese Empire, but it would be 1885 before the British seized complete control of Burma after the Third Anglo-Burmese War.

The First Anglo-Ashanti War actually began in 1823, not 1824. (Bear with me.) The war began with a territorial dispute between the Ashanti Empire and the Fante, which was a client state of Great Britain. The British governor of the region rejected the Ashanti claims, which should come as a surprise to no one. He arrogantly chose to lead a small British force against an Ashante army that was four times its size. in which the forces of the Ashanti Empire crushed British forces in the Gold Coast. On January 22, 1824, the Ashanti defeated the British at the Battle of Nsamankow. Later that year, they again defeated the British and their African allies at the Battle of Efutu. The war ended in 1831, with a negotiated border. The British and the Ashanti fought four more wars between 1863 and 1900, which ended with the Ashanti empire incorporated into the British Gold Coast Colony. (Are you seeing a pattern here?)

Lord Byron. Courtesy of the British National Portrait Gallery

On April 29, the British poet lord Byron died of a fever at Missolonghi. He had arrived in Greece on Christmas Eve, 1923, to join the Greek fight for independence, which had begun in 1821. His arrival in Greece had little practical impact on the war, but his presence there, and especially his death, caught the imagination of philhellenes across Europe.

The Surrender at Ayacucho

On December 9, South American republican forces under the leadership of Antonio José de Sucre*** won a decisive victory over Spanish colonial forces at the Battle of Ayacucho in Peru. The battle was the last major confrontation in the Latin American wars of independence. The victory secured the independence of Peru, which had been declared in 1821, and was the tipping point in the Latin American revolutions as a whole .

In related news, border disputes are settled

Britain and the Netherlands signed the Anglo-Dutch Treaty, which resolved territorial disputes between the British Empire and the Netherlands that resulted from the British occupation of Dutch colonial territories in the Malay Peninsula and the Spice Islands during the Napoleonic Wars. (Though in fact the two colonial powers had been butting heads in Southeast Asia since the 17th century.)

The United States and Russia sign a treaty settling their dispute about the boundary between the United States and Russian Alaska. Russia ceded all lands south of the parallel 54° 40’ north, known to Americans as the Oregon territory.

Other political stuff

There were four candidates in the presidential election of 1824: Andrew Jackson, John Quincy Adams, Henry Clay and William Crawford. When the vote was tallied, Jackson had a plurality of the popular vote, at 40.5%, but none of the candidates had enough electoral votes to win. Even so, Jackson had more electoral votes than the others—99 compared to Adams with 84, Crawford with 41 and Clay with 37. Acting under the Twelfth Amendment of the Constitution, the House of Representatives met to select the president from the top three candidates. Each state had one vote, determined by the majority of its congressional representatives. Clay having been eliminated from the race, most of his supporters switched their votes to Adams, giving John Quincy a one-vote majority and the presidency. Jackson was furious at losing the election to what he termed a “corrupt bargain” between Clay and Adams to overturn the will of the people. In other words, the electoral college has been an issue for debate for a long, long time.

Violent upheavals in the kingdoms of southern African in the early 19th century, a period known as the Difaqane, or “crushing”, resulted in smaller kingdoms being absorbed by larger, stronger kingdoms. In 1824, the leader of one of these strong kingdoms, Moshoeshoe I, occupied the mountain stronghold of Thaba-Bosiu. From this secure capital, he consolidated disparate groups into the powerful Sotho kingdom. Under his leadership, Sotho survived attacks by the Zulu, the Boers and the British for much of his reign.

The first constitution of Mexico was ratified on October 4, 1824, creating the First Mexican Republic. (It would not be the last.) The constitution was drafted after the demise of the short-lived rule of Emperor Agustin I. ****

New Ideas

Lithograph from William Buckland’s “Notice on the Magalosaurus or great Fossil Lizard of Stonesfield”

British paleontologist and fossil hunter,William Buckland presented the first scientific description of a dinosaur, which he named Megalosaurus. (The short accounts all say this is the first dinosaur to be validly named in scientific terms—I do not know what this means, though I suspect it takes me back to Swedish biologist Carl Linnaeus, who has been tracking me down.) He made a number of paleontological discoveries, including a skeleton which he named “the Red Lady of Paviland after the location where it was found. The skeleton, now known to be male, has been dated to ca 30,000 BP, i.e. “Before Present” and is the oldest modern human found in Britain. He developed the study of fossil feces, which he dubbed coprolite, the term still used today. On the other hand, he is also known for his efforts to reconcile geological studies with the Bible. People are complicated.

Beethoven composed his Ninth Symphony. Need I say more?

*A reminder that there is always another side of the battlefield.

**The British East India Company functioned as a semi-political entity in India until 1857, when the Company’s possessions became a Crown colony. (A brief pause here while I re-read several of my posts related to the British East India Company’s political power and try to decide whether to link to one. Let’s try this one: Poor Tipu )

***De Sucre was Simón Bolívar’s chcief lieutenant during the Latin American wars wars of independence. He later became the first constitutionally elected leader of Bolivia.

**** Agustin was an officer in the Spanish army who switched sides during the Mexican War of Independence to lead a rebel force. After Mexico won its independence in 1821, he was proclaimed first president and then emperor. (Am I the only one who sees Napoleonic echoes here?) Regardless of how Agustin became emperor, there was considerable discontent during his reign, which culminated in a revolt led by Santa Anna. (Who I had heard of, but know little about.) Agustin abdicated in March, 1823 and went into exile in Europe. When he returned to Mexico in July 1824—after the new constitution had been drafted but before it had been ratified—he was arrested and executed as a traitor. In 1838, his ashes were carried to Mexico City, where he was buried with honors as a hero of the revolution.

December 9, 2024

1724: A Year in Review

For those of you who care about such things. 1724 was a leap year, giving us an extra day in which stuff could happen—and happen they did.

Royal Heads

King Philip V, the first Bourbon of Spain,* abdicated in favor of his sixteen-year-old son, Louis I on January 14. I have read several reasons why he made this unusual decision. The most compelling is that he was showing signs of serious mental decline snd made the responsible choice to step aside. Whatever his reasons, fate overturned his decision. Louis died of smallpox on August 31. Six days later Philip reluctantly resumed the throne to avoid a regency for his second son, Ferdinand, who was only ten. His combined reign, which totaled 45 years and 16 days, was the longest in the history of the Spanish monarchy.

Tsar Peter the Great crowned his wife Catherine I** as his co-ruler on February 8. When Peter died the following year without naming a successor, a coalition of the “new men”*** and regiments of the imperial guards proclaimed her the ruler. (Can you call it a coup if there is no one on the throne to overthrow?) Catherine ruled until her death two years later.

The Hapsburg Emperor Charles VI**** appointed his unmarried sister, the Archduchess Maria Elisabeth of Austria, as governor of the Austrian Netherlands (modern Luxembourg and Brussels). She held the position until her death in 1741. It was not an unusual choice. The Hapsburgs regularly placed unmarried women of their royal house as regents over provinces in their widespread empire. The Netherlands in particular were ruled by an almost unbroken succession of ruling duchesses for almost sixty years—each the niece of her predecessor. Maria Elizabeth seems to have been trained for the position. She enjoyed an above average education at the hands of professors from the university in Vienna and was competent in five languages.

Yeongjo became the 21st ruler of the Joseon dynasty of Korea.**** He ruled for almost fifty-two years. His reign appears to have been a period of political, economic, and social reform, inspired by a deep adherence to Confucian morals. (Can anyone recommend the equivalent of The Joseon Dynasty for Dummies? Or perhaps Korean History for Dummies? This is a huge hole in my historical knowledge.)

Ideas, and Reactions to Ideas

In Qing China, the Yonghzheng Emperor banned the teaching of Christianity—sort of. Catholic missionaries had been active in China since 1602, when Matteo Ricci arrived in Beijing and in fact Jesuit priests had long proved useful as advisors to the court on astronomy and scientific matters. But missionaries working in the provinces were seen as threatening to a Confucian society. The ban reflected that division: foreign priests were allowed to remain in the capital but missionaries working outside Beijing were required to move to the Portuguese enclave at Macau. Qing subjects were prohibited from practicing Christianity—which may or may not have worked. It is hard to enforce belief.

Glassblower Gabriel Fahrenheit developed the Fahrenheit temperature scale. He had previously invented the first precision thermometer, using mercury instead of alcohol. (And because it was the obvious question to ask: Swedish astronomer Anders Celsius developed his competing temperature scale in 1742.)

Jonathan Swift, published seven satirical pamphlets under the pseudonym M.B. Drapier in which he sought to rouse public opinion in Ireland against a patent that allowed a private contractor in England to minted copper coins to be distributed in Ireland. Swift, and others, objected to the coinage because there were no safeguards to insure the purity of metal used, they believed bribery had been involved in issuing the patent, and widespread resentment about Britain’s colonial control of Ireland’s economy, including control over minting its currency. “Mr. Drapier” became a central figure in the controversy and was treated as a folk hero by the Irish after the British government withdrew the patent.

Johann Sebastian Bach led the first performance of his St John Passion in Leipzig on Good Friday. He was a new director of music at the St. Thomas church, and was the congregation’s second choice for the position. As such, he was determined to prove himself with the production of a new work with which to break the Lenten music fast. And prove himself he did.(It was a busy year for Bach. He also wrote his second cantata cycle, totaling 53 new works He also began what would be a twenty-year collaboration with librettist Picander (Christian Friedrich Henrici.)

* Just in case you’re interested, Philip was born into the French royal family. But his grandmother was the half-sister of the last Hapsburg ruler of Spain, Charles V, who died childless. (His great-grandmother was also a Spanish Hapsburg.) Philip’s accession to the throne led to the War of Spanish Succession because other European powers were worried that uniting France and Spain under a single Bourbon monarch would upset the balance of power. The end result was two Bourbon kings who ruled over two important states.

** NOT to be confused with Catherine II, commonly known as Catherine the Great, who seized the throne from her husband Peter III in 1762 and reigned as empress for 34 years, 4 months, and 8 days—but who’s counting?

***Commoners whom Peter had placed in positions of power based on their competence. They stood opposed to traditional aristocrats. Or more likely, traditional aristocrats opposed them.

****It’s hard to avoid the Hapsburgs.LINK

****I hadn’t heard of him either. Which is one reason to include him here. One of the purposes of these posts is to look briefly at a broad range of historical incidents. (If any of you think these year in review posts are a quick and dirty way to create new posts in the rush of the holiday season, you would be wrong. Each one of them takes somewhere between several and many hours to produce. Just saying.)

December 6, 2024

The Queens of Animation

Nathalia Holt’s The Queens of Animation: The Untold Story of the Women Who Transformed the World of Disney and Made Cinematic History is a good example of what has become a genre in the world of women’s history: the exploration of a group of women within an industry or profession whose contribution was critical and yet has been largely overlooked. Margot Lee Shetterly gave us a name for them “hidden figures.”

As with so many of these books, Queens of Animation begins with the author’s discovery of a missing element in an often told story. Doing research for a different book, Holt interviewed a woman who told her about working for the Walt Disney Studios in the 1930s and 1940s. To Holt’s surprise, her interview subject’s stories were full of women artists working in the studios, as animators as well as members of the largely female Ink and Paint department, who traced animators’ sketches onto plastic sheets and brought them to life with color.

Holt was well aware that these women’s names did not appear in the credits for the animated features they worked on*—she had spent many hours of a cartoon-obsessed childhood watching the credits role past and looking for women’s names.** Interested in learning more, she picked up one of the many biographies of Walt Disney only to find that the women whose names she had learned didn’t appear. In a second biography, two of the women were mentioned, though their accomplishments were not. In fact on, Mary Blair, who had been an art director at Disney for decades and whose work had defined the style for many of Disney’s most important films, was mentioned merely as the wife of another, less important artist. Finding no trace of the women or the contributions in the existing histories of the company, she sent in Wearch of the women themselves.

The result of that search is a multi-layered group biography of the women, the art they produced, the challenges they faced, and their contribution to Disney films. Along the way, she also discusses the changing technology of animation, something I knew little about and found absolutely fascinating.

If you are interested in “hidden figures” or the history of animation, this one is for you. Be warned, it may make you want to go back and watch Disney films with a new eye to the artistry.

*This is an astonishing example of erasing women from the story even as it unrolls.

**I swear, the stories find the writer, not the other way around.

December 2, 2024

1624: The Year in Review

In 2013, I wrote my first A Year in Review post: for some reason that I no longer remember I had been spending a lot of time thinking/reading/writing about 1913 and wanted to share some of the highlights. Over the next few years, Year in Review posts became a standard part of December here on the Margins. I let them slip for the last two years, mostly because I was so deep in the life and times of Sigrid Schultz. It’s a shame: 1923, for example, was quite a year.*

This year, it’s time to renew the tradition, kicking off with 1624.

❦❦❦❦

In the New World:

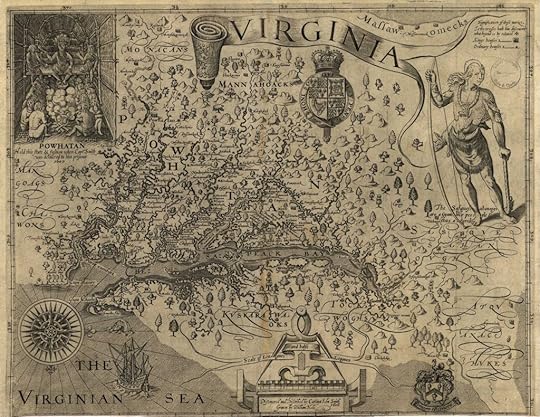

Captain John Smith’s map of Virginia, dated 1624

The Virginia Company, which owned Jamestown, the first permanent English settlement in North America, was bankrupt. King James I of England** (and VI of Scotland) revoked the company’s charter on May 24 and made Virginia a crown colony. A year later the colony of Virginia butted heads with the crown for the first time. The colonists petitioned the king (now Charles I) for the right to retained their own legislature. Charles refused. Apparently legislation without representation was an issue earlier than I realized.

Also in Jamestown that year, William Tucker was born. He was the first known Black child born in English colonies of North America. He was the son of two Africans who were among the first group of Africans to be brought to North America in 1619 by Portuguese slavers. The group were technically sold to English settlers as indentured servants, but unlike their European counterparts they did not enter this indenture freely. Also unlike their European counterparts, their children were born into slavery. Slavery, too, was an issue in the North Americana colonies from the beginning.

The Dutch West India Company established its own trading post on the Atlantic shore. New Amsterdam was part of the larger colony of New Netherland which included what is now New York City and parts of Long Island, Connecticut and New Jersey.

Sir Thomas Warner founded the first British colony in the Caribbean on St. Kitts.

The Dutch seized the capital of Spanish/Portuguese Brazil, after two previous attempts in 1599 and 1604. Their goal was control over the lucrative sugar trade, which was a very big deal.

In the larger world:

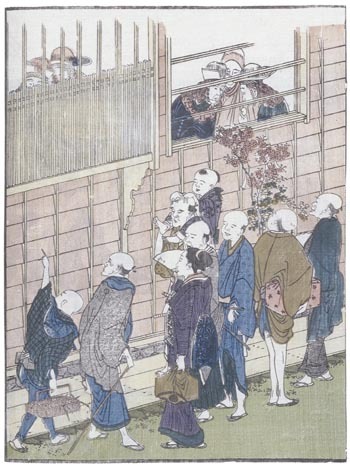

Curious Japanese watching Dutchmen on Dejima Island. Katsushika Hokusa. ca 1802.

The Japanese Shogun expelled the Portuguese and cut off trade with the Philippines, the first step in closing Japan to the west. (Some historical timelines say the Japanese expelled the Spanish. This is technically true. Portugal became part of Spain in 1580. But Portugal’s presence in Japan occurred as part of the Portuguese maritime exploration and subsequent trade empire.)

The English and Dutch were expanding their territories in Asia as well as in the New World. The Dutch East India Company established trading posts on the coast of Taiwan. The English established trading posts in eastern India.

Thanks to well-chosen dynastic marriages and New World wealth, Hapsburg Spain was the Big Bad for the rest of Western Europe over the course of the seventeenth century. In 1624, France and the Netherlands signed the Treaty of Compiègne, a mutual defense treaty designed to isolate Spain. Egged on by Cardinal Richelieu of France, England, Sweden, Denmark-Norway, Savoy and Venice coordinated action against Spain. It all fell apart in 1625, when the Huguenot rebellion distracted Richelieu

DCF 1.0

Meanwhile in Eastern Europe, Hungarian King Bethlen Gabor and Ferdinand II, who was then ruler of the Hapsburg [!!] Duchy of Lower and Inner Austria and may have been the Holy Roman Emperor,*** signed the Treaty of Vienna, ending the Bohemian phase of the Thirty Years War**** and strengthening Ferdinand’s position the Hungary. This may feel like an obscure event from the perspective of those of us whose history classes focused on American history, but was actually a big deal.

On a smaller scale:

Frans Hals painted The Laughing Cavalier. (An occasional image helps me place things in history. Also, a painting I’ve always loved. )

English mathematician William Oughtred invited the slide rule, building on John Napier’s invention of logarithms and Edmund Gunter invention of logarthmic scales.

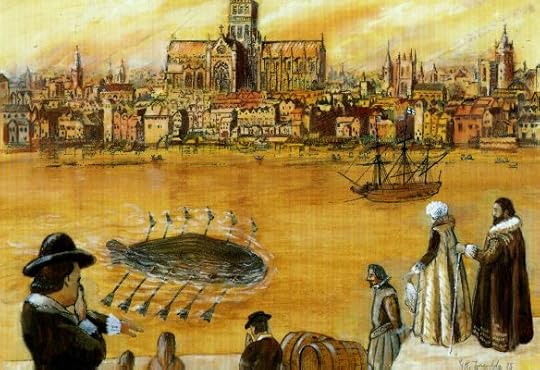

Unlikely as it sounds, the first successful submarine, designed by Dutch inventor Cornelius Drebbel was publicly tested in London on the Thames before an audience of thousands, including King James. The submarine was built on a wooden frame covered with leathered and powered by oars. It submerged for three hours and traveled from Westminster to Greenwich and back—six nautical miles each way. King James took a test dive, but the British Royal Navy wasn’t interested in exploring the technology further.

Van Drebbels’ submarine in the Thames

*The USSR was formed. King Tut’s tomb was opened. Hyperinflation made life difficult in Weimar Germany. It became legal for women to wear trousers in the United States. Etc, etc, etc.

**Also, and originally, James VI of Scotland.

***Untangling the Hapsburg dynasty and its march to what became the Austro-Hungarian Empire is complicated. I definitely don’t have a handle on it.

** Here’s the short version: Reformation vs Counter-Reformation. Here’s a slightly longer version: The Third Year’s War was actually a series of wars, in which Protestant and Catholic princes battled for control of the Holy Roman Empire. The conflict began when the Protestants of Bohemia rebelled against Emperor Ferdinand II, but soon spread throughout the empire and included most of the European powers at one point or another.

November 27, 2024

Counting My Blessings

I keep looking for another vintage Thanksgiving postcard, but most of them have creepy children wielding axes. Not my vision of Thanksgiving.

It is Thanksgiving here in the United States, and I have a LOT to be thankful for this year, including the fact that I am at home cooking Thanksgiving dinner.*

In a few minutes I will begin several hours of peeling, chopping, stirring, and roasting, with an occasional pause to put my feet up and count my blessings. Before I head downstairs to pull the turkey out of the refrigerator,** I want to take a moment to thank all of you who read History in the Margins, share my posts with your friends, send me e-mails, ask hard questions, point out mistakes, give me ideas for new posts, and cheer me on. Without you, I’d just be talking to myself.

*A week and a half ago, we were making contingency plans for who was going to cook the heritage turkey that was due to arrive a few days before the holiday in case I had to be elsewhere.

**Yes, it is thawed.

_______________________

Speaking of sending me ideas, I am currently issuing invitations to my annual Women’s History Month series of mini-interviews. I have some great people on board already, but I need more. If you “do” women’s history in any format, or know someone who does, or have an idea of someone you would love to see in the series, drop me a line. I’ve interviewed academics, biographers, podcasters, historical novelists, tour guides, and poets, but would be happy to talk to people who explore women’s history through music, puppet shows, graphic novels, the visual arts, interpretive dance….

November 25, 2024

In which I finally review Headstrong: 52 Women Who Changed Science—and the World

Journalist Rachel Swaby’s Headstrong: 52 Women Who Changed Science—and the World is the source of one of my favorite descriptions of the work I do as a writer of women’s history: “revealing a hidden history of the world.”

Swaby was inspired to write her collective biography of groundbreaking women scientists by an obituary which appeared in the New York Times in March, 2013. The obituary began by reporting that Yvonne Brill made a mean beef stroganoff, that she followed her husband from job to job, and took eight years off to raise three children. Only then did the Times mention the reason she had earned an obituary: she was a brilliant rocket scientist who won the National Medal of Technology and Innovation for her development of a propulsion system that keeps satellites in their orbits, a system which became the international standard. As someone who also makes a mean beef stroganoff, I can assure you that the two accomplishments are not equivalent.

The Times quickly amended its article to begin with the rocket science after a loud public outcry, but the original obituary led Swaby to consider the way women’s careers and accomplishments in science have been, and unhappily continue to be, underreported. The result is Headstrong, a collection of brief biographies of women who have made lasting contributions to science. At the time the book came out in 2015, I had only heard of a handful of the women whose stories she tells: Rachel Carson, Rosalind Franklin, Irène Joliot-Curie,* Sally Ride, and Ada Lovelace. In the intervening years a number of others that Swaby introduced me to have become well-known, at least in those circles interested in women’s history. Others I know only from the pages of Headstrong.

The book is structured as a series of essays, perfect for dipping into when you need a bit of women’s history to remind you that we were there. (Swaby suggests that you read one a week over the course of a year. I was not that disciplined.)

If you know a girl who is interested in STEM and would like to know where she fits in a world that is still heavily male, Headstrong would be a nice place to start the search for role models.

*Who I knew only because she was the daughter of Marie Curie and, like her mother, won a Nobel Prize for chemistry. Swaby chose not to include Marie Curie because she is the woman “we talk about when we talk about women in science.”

November 21, 2024

From the History in the Margins Archives: McCarthyism and the Red Scare, Part 2. Attacking “Communists”, and Anyone Else Who Got In His Way

If it seems to you that I’ve run a lot of posts from the archives lately, you would be right. At the moment, I am overwhelmed by life stuff and simply don’t have the bandwidth to write new posts on a consistent basis. Instead of letting the blog go dark, when I don’t have something new to say I will continue to share old posts that I feel you might enjoy or that seem relevant to the moment. Thanks for reading along. There will be new stories in the not too distant future. Honest.

Joseph Nye Welch, chief counsel for the US Army, being questioned by Joseph McCarthy

If you’re coming in late to the party, you may want to read the previous post. Here’s the short version: in 1948 Joseph McCarthy won a seat in the US Senate with a dirty campaign and began his senatorial career with a press conference calling for striking miners to be drafted, court-martialed, and then shot. Here’s what happened next:

By 1950, McCarthy’s Senate career was in trouble. The fact that he had lied about his war record during the election campaign had become public. Moreover, he was under investigation for tax offenses and for accepting bribes from Pepsi-Cola to vote in favor of removing wartime restrictions on sugar.

McCarthy directed public attention from his own problems by going on the attack. On February 9, 1950, while speaking to a group of Republican women in Wheeling, West Virginia, McCarthy announced that he had a list of 205 State Department employees who were “card-carrying” members of the American Communist Party,* some of whom were busy passing classified information to the Soviet Union.

When the Senate Committee on Foreign Relations asked McCarthy to testify, he was unable to provide the name of a single “card-carrying communist” in any government department. Undeterred by the absence of facts, McCarthy began an anti-communist campaign in the national media. His first step was claiming communist subversives had infiltrated President Truman’s administration. When the Democrats accused McCarthy of using smear tactics, he claimed that their accusations were part of the communist conspiracy.

As a result of McCarthy’s tactics, the Republicans swept the 1950 elections. Having watched him use scare tactics to discredit his opponents during the election, the remaining Democrats in Congress were reluctant to criticize him. McCarthy, whom the Washington press corps once voted “the worst US senator”, was now one of the most powerful men in Congress.

After being re-elected in 1952, McCarthy became the chairman of the Senate’s Committee on Government Operations, and more importantly of its permanent investigation subcommittee. In an ironic mirror image of Stalin’s trials of alleged counter-revolutionaries,** McCarthy used his position to hold hearings against individuals whom he accused of being communists and government agencies that he claimed harbored them. He attacked journalists who criticized his hearings. He campaigned to have “anti-American” books removed from libraries. He accused newly elected Republican president Dwight Eisenhower of being soft on communism.

McCarthy ran into trouble in April, 1954, when he turned his attention to supposed communist infiltration of the United States Army. The army fought back by providing information to journalists known to oppose McCarthy, including evidence that McCarthy had tried to use his influence to get preferential treatment for his aides when they were drafted. The end came with the decision to broadcast the “Army-McCarthy” hearings on national television. For thirty-six days Americans watched from their living rooms as McCarthy bullied witnesses and offered evasive answers to questions. At one point, after McCarthy attacked a young Army lawyer, the Army’s chief counsel, Joseph Nye Welch, demanded “Have you no sense of decency, sir?”

By the end of the hearings, McCarthy had lost most of his allies and the trust of the American people. Later that year, with a vote of sixty-seven to twenty-two,*** the Senate officially censured McCarthy for conduct “contrary to Senate traditions.” He remained in office, but had no power beyond his senatorial vote. (Which is not nothing.) He died before the end of his second term, leaving as his legacy a cautionary political tale of popular fear, demagoguery, abuse of power, and the value of a democratic system of checks and balances.

*Personally, I doubt that the American Communist Party issued membership cards at the time. It was a disorganized group prone to fracturing along theological lines.

**Ironic from an historical perspective. It is unlikely that McCarthy intended the irony.

***Alaska and Hawaii were not yet states. But unless I’m doing the math wrong that still means some senators must have abstained or taken a convenient bathroom break.

Save

November 18, 2024

From the History in the Margins Archives: McCarthyism and the Red Scare. Part 1, Dirty Tactics

If it seems to you that I’ve run a lot of posts from the archives lately, you would be right. At the moment, I am overwhelmed by life stuff and simply don’t have the bandwidth to write new posts on a consistent basis. Instead of letting the blog go dark, when I don’t have something new to say I will continue to share old posts that I feel you might enjoy or that seem relevant to the moment. Thanks for reading along. There will be new stories in the not too distant future. Honest.

Senator Joe McCarthy* and the Red Scare of the 1950s have been on my mind a lot lately. McCarthy took the very real fear many Americans felt about the spread of communism** and turned them into an official witch-hunt for his personal political benefit.

Born to a Wisconsin farm family in 1908, McCarthy left school at fourteen. He worked as a chicken farmer and a grocery store manager before he went back to high school at the age of twenty. He went on to get a law degree from Marquette University. Up to this point, McCarthy’s career looks like a textbook example of the American dream.

In 1948, McCarthy was elected to the United States Senate in an upset victory over the incumbent senator, Robert LaFollette, Jr. LaFollette was a second generation progressive Republican senator.*** His seat in the senate seemed so secure that people said if “Little Bob” could be unseated anyone could be unseated.

McCarthy fought a dirty campaign. He lied about his war record, claiming to have flown thirty-two missions during World War II when he actually worked a desk job and only flew in training exercises. LaFollette was too old for military service when Pearl Harbor was bombed, but McCarthy attacked him for not enlisting and accused him of war profiteering. Ad hominem attacks make for sexy headlines. Fact checking does not. McCarthy won the election.

On his first day as a senator, McCarthy called a little-noticed press conference that was a dress rehearsal for his later performance as a demagogue. He had a modest proposal for ending a coal strike that was in progress: draft union leader John L. Lewis and the striking miners into the army. If they still continued to strike, he argued that they should be court-martialed for insubordination and then shot.

It was an ugly start to a career that would get even uglier.

*Not to be confused with Minnesota senator Eugene McCarthy (1916-2005), who was the opposite of the early Senator McCarthy in pretty much every way possible.

**Whether those fears were legitimate is another question all together.

***Yes, you read that correctly. A progressive Republican. So progressive that he was accused of being a fellow-traveler with communists. The world has changed.

November 15, 2024

From the History in the Margins Archives: History and a More Just Future

If it seems to you that I’ve run a lot of posts from the archives lately, you would be right. At the moment, I am overwhelmed by life stuff and simply don’t have the bandwidth to write new posts on a consistent basis. Instead of letting the blog go dark, when I don’t have something new to say I will continue to share old posts that I feel you might enjoy or that seem relevant to the moment. Thanks for reading along. There will be new stories in the not too distant future. Honest.

First up, a review of a book that I think is even more important than it was when I first told you about it two years ago.

Last December, My Own True Love and I stopped in Saint Louis on our drive from Chicago to my hometown in the Missouri Ozarks. We spent two hours at the Gateway Arch. The museum at the base of the arch had been completely renovated since our last visit, thirteen years previously. I was delighted to see that the story of westward expansion had been, well, expanded. Women and people of color were explicitly included,* as was the United States’ aggressive actions against Native Americans in general and against Mexico in the 1840s. The exhibit told the story of lost rights and imperial actions alongside stories of material progress, courage, and growth.

I talked about the changes in the way the National Park Service tells the story in some detail in a blog post about our visit. What I didn’t share in that post was the way the exhibits made me feel. By the end of that two hours, my head throbbed, my stomach hurt, and my heart ached. Holding the two stories side-by-side was painful. History is my passion. But over the last few years, I’ve also learned that history is hard. And I’ve come to believe that it should be.

Which brings me to Dolly Chugh’s new book, A More Just Future: Psychological Tools for Reckoning with Our Past and Driving Social Change. Dolly deals directly, and brilliantly, with the discomfort increasing numbers of us are trying to come to terms with about the disjunction between the history we were taught and the history we weren’t taught. Her goal is to help us, and herself, “appreciate both the reality of our country’s mistakes and the grandeur of our country’s greatness”—a condition she defines as being a “gritty patriot”—and further, to understand the impact of our past on our present.

Dolly is a social psychologist, not a historian, so the focus of her book is not on the buried/forgotten/overlooked tales of our past,** though she uses some of those stories to illustrate her points. Instead she helps the reader understand why is it so difficult, emotionally and intellectually, to unlearn history—as individuals and as a country—and gives her (and by her, I mean me) tools for doing so.

A More Just Future is an important and wise look at confronting our whitewashed history and the emotional impact of doing so. It is also a delight to read. Trust me on this.

* A trend you’ve seen me applaud many times in these posts and in my newsletter over the last few years.

**Or more accurately, the stories left out of mainstream accounts of our collective history.

Just so you know: Dolly Chugh is a Harvard-educated, award-winning social psychologist at the NYU Stern School of Business, where she is a expert researcher in the psychology of good people. In 2018, she delivered the popular TED Talk “How to let go of being a “good” person—and become a better person.” She is also the author of the acclaimed book The Person You Need to Be and the popular newsletter Dear Good People. [Both of which I strongly recommend.]

You can find out more at DollyChugh.com.

November 11, 2024

From the History in the Margins Archives: The Great Silence

Whether you know it as Armistice Day, Poppy Day, Remembrance Day or Veterans’ Day, November 11 is a time to honor those who died in war and thank those who served.

The day of remembrance has its roots in the end of World War I. The war ended on November 11, 1918. When the word reached England that the the armistice had been signed, the country broke out into a spontaneous party. (The Savoy Hotel alone lost 2700 smashed glasses to the celebration.) No stiff upper lip allowed.

When the first anniversary of the Armistice drew near, dancing in the streets of a post-war world no longer seemed appropriate . Neither did letting the day go unnoticed. Some assumed that special church services were the proper response. Australian soldier and journalist Edward George Honey wrote a letter to the London Evening News suggesting a moment of silence “on the eleventh hour of the eleventh day of the eleventh month”. He asked for “Five silent minutes of national remembrance…Church services too, if you will, but in the street, the home, the theatre, anywhere, indeed, where Englishmen and their women chance to be, surely in this five minutes of bitter-sweet silence there will be service enough.”

Honey asked for five minutes; he got two. King George V called for all Britons to stop their normal activities “so that in perfect stillness, the thoughts of every one may be concentrated on reverent remembrance of the glorious dead.”

If you can, at the eleventh hour of the eleventh day of the eleventh month–pause for a moment. If you can’t? Thank a veteran. Buy a poppy, if you can find one. Pray for peace.