Pamela D. Toler's Blog, page 13

November 4, 2024

The Thrill of the Vote

This post first ran on election day in 2008. I’ve run it several times since then. My feelings on the subject haven’t changed:

It’s election day in Chicago. I just walked home from voting for a new mayor and a new alderman–and I miss my old neighborhood.

For ten years I lived in South Shore: a white graduate student/small business owner/writer in a neighborhood dominated by the African-American middle class. My neighbors were police officers, schoolteachers, fire fighters, electricians, and social workers. We didn’t have much in common most of the year–except on election day.

As far as I’m concerned, voting is thrilling. My South Shore neighbors agreed. Voting in South Shore felt like a small town Fourth of July picnic. Like Mardi Gras. Like Christmas Eve when you’re five-years-old and still believe in Santa Claus. No matter what time of day I went to vote, my polling place was packed. Voters and election judges greeted each other–and me–with hugs, high fives, and “good to see you here, honey”. First time voters proudly announced themselves. Elderly voters told stories about their first election. People made sure they got their election receipts; some pinned them to their coats like a badge of honor. An older gentleman sat next to the door and said “Thank you for exercising your right to vote” as each voter left. The correct response was “It’s a privilege.”

Except for occasional confusion when the machine that takes the ballots jams, my current polling place is low key. Election judges are friendly and polite, but hugs are not issued with your ballot. When the young woman manning the machine handed me my receipt, she told me to have a good day. I said “It’s always a good day when you get to vote.” In South Shore, that would have gotten me an “Amen.” In politically active, politically correct Hyde Park, it got me an eye-blinking look of surprise and a hesitant smile.

I started home, thinking maybe I was the only one in the neighborhood whose pulse beat faster on election day. A block from the polls I ran into a young man walking with a small boy, no more than six years old. The little boy stopped me, with a grin so big that he looked like a smile wearing a woolly hat.

“Did you vote yet?” he asked. “My dad is taking me to teach me how to vote.”

“It’s a privilege,” I said.

He gave me the highest five he could manage.

* * *

So tell me, did you exercise your right to vote? It is indeed a privilege.

October 31, 2024

From the Archives: You think one vote doesn’t matter? Hah!

I have told this story here on the Margins before. But with the presidential elections only a few days away, I think it’s important to remember right now that the 19th Amendment was ratified thanks to one man’s vote.

In August, 1920, 35 states had ratified the amendment; 36 states were needed for it to pass. Tennessee was the only state still in the game. Proponents and opponents of the amendment gathered in a Nashville hotel to lobby legislators. The press dubbed it the War of the Roses because supporters of the suffrage movement wore yellow roses in their labels while its opponents wore red roses.

On August 19, the vote appeared to be tied, assuming the count of red and yellow roses was correct. When the roll call came, 24-year-old Harry T. Burn stepped into history. Burn came from a very conservative district and wore a red rose in his label, but when asked whether he would vote to ratify the amendment he answered “aye”. What changed his mind? A letter from his mother, Febb Burn, who told him to “be a good boy” and vote in favor of the amendment.

Asked later about his change of heart, Burn said “I knew that a mother’s advice is always safest for a boy to follow and my mother wanted me to vote for ratification. I appreciated the fact that an opportunity such as seldom comes to a mortal man to free 17 million women from political slavery was mine.”

If you have the right to vote, use it. Because one vote can in fact change the world.

October 28, 2024

From the Archives: You Can’t Vote Because

I first ran this post in 2011. I think it is an even more important reminder today.

From sixth century Athens on, who has the vote and why has been a touchy and evolving subject in democracies. People who already have the vote have hesitated to extend it to others for two basic reasons. Those with the vote don’t think those without the vote have the capacity to make good choices. Those with the vote fear they will lose power.

Over the centuries, people in power have come up with plenty of reasons not to extend the franchise to those who don’t yet have it. Here are a few of the classics:

You can’t vote because

You’re a slaveYou’re a womanYou don’t own propertyYou don’t own enough propertyYou don’t practice the right religionYou are the wrong race or ethnicityYour father or grandfather couldn’t voteThe United States presidential election is next Tuesday. If you’re lucky enough to have the vote, use it.*

*This is a handy primer on exercising you voting rights in the United States: https://www.aclu.org/know-your-rights/voting-rights Pass it on to anyone you think might need it.

October 24, 2024

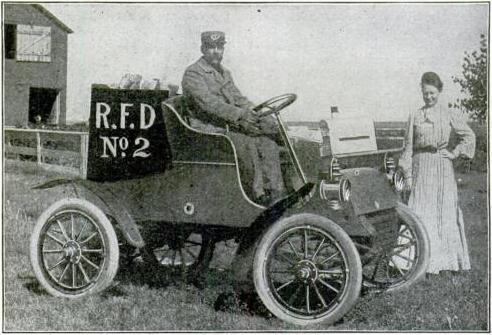

From the Archives: Rural Free Delivery

Over the last several months, I have been working my way through a stack of “get out the vote” postcards: writing as legibly as possible. (Always a challenge for me.) Now I’m at the deadline and writing a little more quickly and a little less legibly. *

Since I am under a bit of pressure here, it seems like a good time to share a post about the American postal service which originally ran in October 2022.

*If you get one of my cards, don’t spend any time trying to read the message. Here’s the short version: Vote!

Every time we take a road trip, we miss one or two or twelve things we would like to see because they were closed for the season,* or we hit town on the wrong day, or we had the wrong directions,** or we just plain ran out of steam.

In the case of the Rural Free Delivery Postal Museum, in Morning Sun, Iowa, we made an attempt to set up an appointment, but the telephone number on the website was dead. And it was a little too far out of our way to take a chance and just stop by.

But the story the museum celebrates is just too good not to share:

Home mail delivery is something we take for granted in the United States . But in fact, it is a relatively new service. Free mail delivery began in cities in 1863. Rural postal customers—who made up the vast majority of the population at the time— weren’t so lucky. They paid the same amount for stamps as city folk, but they still had to pick up their mail at sometimes distant post offices or pay private companies to deliver it.

In 1896, after several years of advocacy by the National Grange*** and discussion by Congress, Postmaster General William L. Wilson agreed to test the idea of Rural Free Delivery. The service began on October 1, 1896, when five men on horseback set out to deliver mail along ten miles of mountain roads outside Charles Town, Halltown, and Uvilla West Virginia. (Perhaps it was not by chance that West Virginia was Wilson’s home state.) Within a year, the post office serviced 44 routes in 29 states. (The service was so new that regulation mailboxes did not exist. Farmers nailed improvised receptacles on fence corners, including old boots, tin cigar boxes, and shoe boxes.) Customers across the country sent more than 10,000 petitions asking for local routes.

In 1902, Rural Free Delivery became a permanent service of the Post Office. Farm families became a little less isolated.

On a related note: The RFD Museum wasn’t the only postal moment on our trip. When we stopped at the Pine Creek Grist Mill in Muscatine County, Iowa, we learned that the gentleman who founded the mill in 1834 was licensed to run the first post office in the county. The mailing address for any letters coming through the post office was the same: Iowa Post Office, Blackhawk Purchase, Wisconsin Territory. I had never thought about how letters would be addressed on the frontier. Suddenly it became clear to me just how amazing it was that people could send letters to someone who had left home and moved west.

*Word to the wise: If you take a road trip through Minnesota in late September you will miss a lot of stuff.

**As I mentioned in an earlier post, if you want to visit the New Philadelphia archeological site, do NOT put New Philadelphia, Illinois in your GPS. It will take you to an existing town in the other direction.

***For those of you who don’t know: The National Grange of the Order of Patrons of Husbandry, commonly known as The Grange, has been providing support for American farmers since 1867. Originally designed to help rural America recover from the devastation of the Civil War, “Grangers” fought discriminatory railroad pricing, established local buying cooperatives, and, yes, fought for rural mail delivery. Local Grange Halls were often the social heart of rural communities places and worked with Farm Bureaus, Extensions Services and 4-H clubs to educate farm families about the newest methods of farming and household management. Today the Grange is still an active advocate for family farms. Cooperative action at its best.

_____________

For anyone who might be interested, my interview for Q & A with Peter Slen on C-Span will air Sunday, October 27 at 8 and 11 pm Eastern time. If you can’t watch then, it will be available for streaming on-line in the near future.

October 22, 2024

Thinking about Women’s History–an Update

Morning, all: I just realized that though the TEDx talk shows beautifully on the website it didn’t come through on emails. You didn’t even get a live link. I tested it several times, but obviously did not succeed in finding a problem.

If this version doesn’t come through, you can click the header on the original email, which will take you to the post in your browser.

My apolgies. I thought I had figured out all this stuff a long time ago. Evidently not.

October 21, 2024

Thinking About Women’s History, or Herstory if You Prefer

It is the time of year when I spend even more time than usual thinking about women’s history: What does it look like? What does it mean? How do we incorporate women into public history with the goal of making it so mainstream that it no longer needs a qualifier? Who is doing interesting work in the field?

For many of you, March is far away. For those of us who are plotting planning Women’s History Month content, it is practically tomorrow. As long-time readers know, every March I run mini-interviews four days a week with people doing interesting work related to women’s history in a varied of fields and forms. I started the list of people to invite earlier this year. But as always at this point in the year, it is not quite long enough and not as varied as I would like.* That means I have my antenna up for people I might want to invite and cool stuff I might want to share.

Which brings me the Remedial Herstory Project.** I’ve been aware of their work for several years now. The short version is that they work to help school teachers incorporate women’s history into their history curriculum, not just in March but throughout the year. I recently discovered this Tedx talk in which the women at the helm of RHP discuss what that could look like, using what Kelsie Brooke Eckert has dubbed “the Eckert test”.*** If I had more self-discipline I would save it for March. But I don’t.

* Suggestions welcome. Particularly suggestions of people working on women who are not middle or upper class white Americans from the mid-19th to mid 20th centuries.

**In the spirit of full disclosure, and blatant self promotion, I recently recorded a podcast episode for RHP. You can find it here:

***Think a more challenging relative of the Bechdel test, designed for history curricula.

October 17, 2024

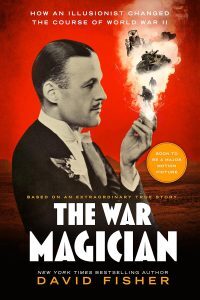

The War Magician

I was well into David Fisher’s The War Magician: How an Illusionist Changed the Course of World War II before I realized that it was a novel based on a true story rather than a work of historical non-fiction. The confusion was mine. The cover clearly states that the story is “based on an extraordinary true story,” which would have given me a clue if I hadn’t been reading it on my Kindle.* My bad.

That said, The War Magician is a fascinating story based on the experiences of Jasper Maskelyne, a famous British stage magician who used his talents at building illusions on behalf of the British army in North Africa. He was the commander of the small “Camouflage Experimental Section,” more popularly known as “the Magic Gang.” Fisher describes how they created the illusion of tanks (and submarines) where there were none and camouflaged naval vessels as pleasure boats and fishing scows. On one occasion, they concealed the entire city of Alexandria from German bombers. On another, their tour de force, they convinced German Field Marshal Rommel that the British planned to attack from the south when in fact they planned to attack from the north, contributing to the British victory at Alamein. I’m not going to give you details, because half the fun of the book is following along as Maskelyne plans his illusions and his crew scrapes together material to create them.

Once I realized that I was reading a novel, I spend some time down the rabbit hole trying to decide just how accurate Fisher’s account is. It isn’t clear. Fisher doesn’t provide a reader’s note discussing his sources.** Ever since the publication of Maskelyne’s 1949 memoir, Magic ,Top Secret, critics have suggested that he exaggerated his importance, though that is hard to prove either way. Exaggerated or not, there is no doubt that Maskelyne and the Magic Gang played a role in the war in North Africa.

The War Magician is worth a read if you’re interested in World War II or stage magicians.

*I seldom read narrative non-fiction on my Kindle because it doesn’t allow me to hold a conversation with the author in the margins and it is difficult to go back and forth between the text and the notes. (Another clue I should have caught: no notes. )

**Or at least he doesn’t in the edition I read, which was released in 2023. The book originally came out in 1983.

October 14, 2024

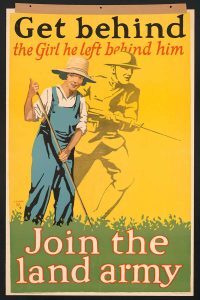

“Farmerettes” Fed the Nation at War

In the fall of 1917, manpower was short in the fields of America. When the United States entered the Great War, millions of men had left farm work to join the army or do other war-related jobs. Even with farm labor wages skyrocketing, farmers faced difficulties hiring men to harvest the crops that were needed at home and in a starving Europe. The federal government did not help when it ignored farmers’ pleas to exempt farm workers from the draft.

While federal and state governments dithered to find solutions, a consortium of women’s organizations—including garden clubs, women’s colleges, civic groups, the YWCA, the DAR, women’s trade unionists, the Girl Scouts and suffrage societies—stepped up to form the Women’s Land Army of America (WLAA), inspired by Britain’s “Land Girls.” More than 20,000 women from American cities and towns, most of whom had never worked on a farm before, learned to tend and harvest crops in training programs organized by the WLAA . Known as “farmerettes,” a term intended to evoke the suffragist movement, they were paid the same wages as male farm workers and were protected by an eight-hour workday—an unknown luxury on many farms then and now. They wore practical uniforms featuring pants (or at least bloomers), initially shocking to the rural communities in which they worked.

Farmers were at first wary about hiring the women. Some of the reasons will sound familiar. Farmers claimed women didn’t have the strength to do the job and didn’t have the necessary skills. One concern was particular to the farmerettes. Farm hands typically were housed on the farm and fed by the farmer’s wife. Farmers were afraid that housing and feeding strange young women would cause domestic upsets. The WLAA solved the problem by housing and feeding “units” of farmerettes in communal camps away from individual farms and transporting them to their jobs each morning.

Wary farmers, and a watching public, were soon convinced as the young women leaned into the work. By the summer of 1918, farmerettes were on the job in thirty-three states, and the subject of poetry, songs, cinema news reels, and acts in the Ziegfield follies.

The organization was resurrected during World War II, this time as an official government effort under the auspices of the US Department of Agriculture’s United States Crop Corps.

October 10, 2024

Mrs. Laura Birkhead and the French Medal of Honor

Back in June, I was poking around in newspapers.com* looking for examples of May Birkhead’s war reporting in World War I. In the process, I stumbled across a fascinating story about her mother, Laura Birkhead (1858-1938)

Mrs. Birkhead was visiting her daughter in Paris when Germany declared war on France on August 3, 1914. Despite the fact that her brother ordered her to come immediately,** she chose to stay and devoted herself to the welfare of first French soldiers, and later French orphans. She founded and ran an American ambulance organization. When the strain of running the ambulance organization became too much for her, she turned it over to others and took charge of a hospital in Paris which treated wounded French soldiers. After the United States entered the war, she also searched for information about missing soldiers at the request of their families.

When thousands of French war orphans began to pour into Paris, she organized an organization called American Volunteer Workers to provide them with housing and clothing. As part of her work, she also organized relief societies back home in Missouri. These groups sent money and millions of pieces of clothing to France for the benefit of French war victims, all of which were shipped directly to Mrs. Birkhead for distribution.***

The fact that Mrs. Birkhead went to school with General John Pershing, head of the American Expeditionary Forces in Europe, may have made her endeavors a little easier. We know she was in touch with him: she received a ham from home that was intended for the general’s Thanksgiving dinner, delivered via a new Red Cross volunteer.

In her own way, Mrs. Birkhead was a much of a war correspondent as her daughter. One of the many small town paper in Missouri which printed her appeals stated that “the description of conditions met with by Mrs. Birkhead is probably the most vivid that has come out of the war zone.” Without the constraints of journalistic ethics, she pulled no punches. In one letter home she told her friends that subscribing to the Red Cross wasn’t enough: “..we may consider ourselves as coming out well by being able to pay out with money…our country will never be devastates, our homes destroyed and polluted, our women violated and our children mutilated. It is impossible to grasp the situation by reading about it. Only seeing is believing. I have seen hundreds of children that have been rescued from destroyed towns that have no idea who they are or where they came from.”**** In another letter, she stated “It is terrible to see the mutilated soldiers, but it is worse to see the almost naked and staved children, with bedraggled and have crazed mothers, with no place to lay their heads…The Germans evidently reasoned ‘If we killed the women and children, France will not have to feed them, but if we leave them naked and hungry she will have them to care for.’ ” Inspired by such accounts, the women of Missouri sewed clothing and collected money for the children’s relief.

When the Germans neared Paris, American citizens were warned to leave the city. Mrs. Birkhead refused to abandon her work. The St. Louis Republic gave her credentials as a special correspondent, which allowed her to stay in the city.

In 1919, before she sailed home, Mrs. Birkhead received what American newspapers called the Medal of Honor from the French government for her relief efforts on behalf of French soldiers. I’m not sure whether they meant the Croix de Guerre or the Legion of Honor.

So many women, so many unexpected stories.

*A very useful site for historical research that is a nightmare to use in my opinion.

**Why he thought that would work is a mystery to me.

***Shades of Clara Barton,who developed a personal supply network to support her work among wounded soldiers in the American Civil War!

****It is worth pointing out that Mrs. Birkhead and her contemporaries who grew up in Missouri would have been children during the American Civil War. They might well have had memories of war horrors. The only state that experienced more battles in the Civil War than Missouri was Virginia.

October 7, 2024

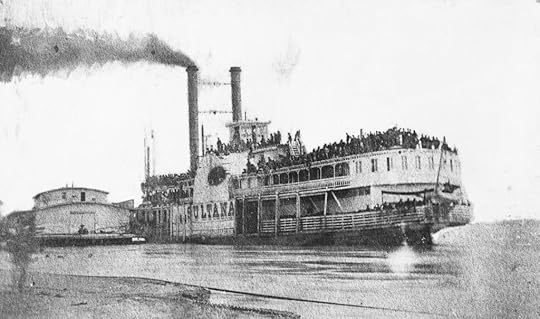

The Wreck of the Sultana

The Sultana, docked at Helena Arkansas, the day before the explosion

On April 23, 1865, only a few weeks after Confederate General Robert E. Lee surrender his troops to General Ulysses S. Grant at Appomattox Court House in Virginia, the steamship Sultana docked in Vicksburg. The Sultana was a 260-foot-long wooden steamboat—about two-thirds of the length of a football field and half as wide.* Built in 1863, it was intended to carry cotton, but instead transported passengers and freight on the Mississippi between St. Louis and New Orleans, which the Union had captured in May, 1862.

The average life of wooden steamboat was only four to five years. The Mississippi River was treacherous and the ships were often badly maintained. The Sultana’s life span was even shorter.

The ship’s captain, J. Cass Mason, stopped in Vicksburg because it had developed a leak in one of its steam boilers. The mechanic who examined the boiler told Mason he needed to cut out and replace the leaking seam—a repair that would take several days.

While in port, Mason received a tempting offer: a lucrative contract to carry former Union prisoners-of-war north to Cairo, Illinois, where they would be transferred to trains. The army’s quartermaster in Vicksburg guaranteed him at least 1000 men, at a rate of $2.75/man and $8.00/officer, if Mason would give him a kickback. Times were tough in the steamboat trade, due to the war, and the contract was big money at the time. Even though boiler explosions were one of the most common causes of steamboat accidents, Mason decided to patch the leaky boiler instead of waiting for the time-consuming repair he needed. Mistake number one.

Mistake number two: Union Army Captain George Williams, the officer in charge of returning the former POWs to their homes, decided to send all the former prisoners then at Vicksburg north on the Sultana rather than dividing them between several ships. The Sultana was designed to hold 376 passengers. Williams loaded more than 1900 union troops and 22 guards on the ship, despite concerns expressed by some of his fellow officers. In addition to the soldiers, the ship carried 70 paying passengers and 85 crew members for a total of 2,128 passengers.

The ship was overloaded and top-heavy. The extra weight and an unusually fast river current caused by the spring thaw put increased pressure on the patched boiler. Early on the morning of April 27, soon after leaving Memphis, the patched boiler exploded, setting off two more. The explosion blew out the center of the ship and setting the rest on fire. Many of the passengers were killed immediately. Others, in poor condition after their time in Confederate prison camps, drowned as they tried to swim to shore in the icy, fast-moving river.. Two hundred died later from their burns. Bodies drifting downriver before they finally came to shore weeks after the explosion,

The wreck of the Sultana was the deadliest maritime disaster in U.S. History, with a conservative estimated death toll of more than 1100. (Some estimates are as high as 1800.) More soldiers died in the wreck than perished in most of the war’s battles.

The sinking of the Sultana never got the attention it deserved, either at the time or in the years since. News of the wreck was overshadowed by the death of Lincoln’s assassin, John Wilkes Booth, Johnson’s surrender to Sherman in North Carolina, and the fact that Jefferson Davis was on the run.

*One of these days I’m going to find a different size comparison. All suggestions welcome.

**To put this in context, official estimates of the death toll on the Titanic come in 1571 or 1503, depending on whether you are looking at the American report or its British counterpart.

![[Suffragists in parade] (LOC)](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1458036539i/18434199.jpg)