Pamela D. Toler's Blog, page 15

August 29, 2024

Road Trip Through History: The Resistance Museum in Oslo

The Resistance Museum in Oslo was not included in our history tour of Norway.* That turned out to be a good thing in my opinion. My Own True Love and I spent the entire morning at the museum on our own the day after the tour ended. We would have been frustrated at being hurried through it as part of a group. And the museum told its own story very clearly. In short, it’s a history bugg must-see if you’re in Oslo.

Here’s the longer version:

The Resistance Museum is unusual in that it was created by members of the resistance. Because the museum is in some ways a historical document writ large, the exhibits have not been updated since it was opened to the public in 1970.** Even without the help of modern museum technology, it is a powerful example of visual story telling. And it was the perfect end to our trip.

Beginning with the first day of the invasion, the museum uses photographs, blown-up newspaper pages, recordings, and artifacts to tell the story of Norway’s resistance to its Nazi occupiers (We were grateful that the museum designers provided English signs alongside the Norwegian.) The museum provides a step-by-step history of the Nazi occupation, giving the larger context and lots of detail for many of the stories we had heard over the tour.

A considerable section of the museum focused on the creation, training, deployment and adventures of the Kompani Linge, which operated as saboteurs and resistance fighters in conjunction with Britain’s SOE (Special Operations Executive). But it did not limit the story to the obvious heroism of armed resistance. It also portrayed acts of civil disobedience against Nazi attacks on personal freedom. After all, heroes don’t always carry guns and blow things up.

Norwegian teachers in the concentration camp near Kirkenes.

If I had to choose a favorite story of the resistance from the museum, it would be the action of Norway’s school teachers, known as the Defense of Education. In 1942, Vidkun Quisling’s proto-Nazi government** created a new Norwegian Teacher’s Union. All teachers were required to join and pledge to teach Nazi principles in the classroom. Almost immediately, an underground group in Oslo sent out a statement for teachers to copy and mail to the authorities, stating that they refused to participate. Roughly 90 percent of Norway’s 14,000 teachers signed the protest statement.

Quisling responded by closing the schools for a month. Not a popular decision. More than 200,000 unhappy parents wrote letters of protest to the government. Meanwhile, many teachers defied the governments orders and held classes in private.

Hoping to break the teacher’s resistance, the government arrested some 1,000 male teachers. In April, the government of occupation sent 499 of those teachers to a concentration camp near Kirkenes, in the arctic. News of the relocation leaked and crowds gathered along the train tracks when the teachers were being transported, singing and giving the prisoners food.****

In mid-May, the Nazis gave up on creating a fascist teachers’ organization. By November, those teachers who survived had returned from the concentration camp. The Nazi curriculum was never imposed on Norway’s schools, thanks to Norway’s teachers.

*For those of you haven’t been reading along, in June My Own True Love and I spent two weeks in Norway on a history-nerd tour run by the Vesterheim Museum. It was fabulous.

**Which is longer ago than I like to think.

***More to come on Quisling in a later blog.

****Not a small gesture given wartime food shortages.

August 26, 2024

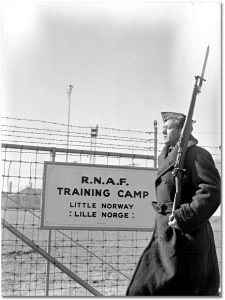

Little Norway and Sigrid Schultz

First, let me say that this post is not about either the now defunct Little Norway living history site in Wisconsin or Little Norway Resort in Minnesota, which are the first things that a Google search of Little Norway will pull up.

Instead it is the story of the main training camp for the Royal Norwegian Air Force during World War II. Or at least a story about the camp. There is probably a story to tell about every man who trained there.

Here goes:

After King Haakon VII and members of the Norwegian government escaped from the Nazis, they formed a government-in-exile in London. They decided to keep those Norwegian military pilots who also managed to escape as a separate, wholly Norwegian military unit.

In the best of all possible worlds, the Royal Norwegian Air Force would have established a training base in Europe.* With most of Europe under Nazi control, the best alternative was Canada. On November 10, 1940, the base known as “Little Norway” went into service outside Toronto. The camp was initially set up at the Toronto Flying Club’s airport on the Toronto Islands. Hundreds of young men escaped from Norway through Sweden or by way of the North Sea and found their way to Canada to enlist in the new service—a trip that in many cases required a heroic effort. The islands soon proved to be too small and the base was relocated to Muskoka Airport, north of Toronto. More than 3300 Norwegian air men and ground crews would train at the camp.

The first Norwegian squadron arrived in Iceland in April 1941. They patrolled the North Atlantic looking for German submarines. The second, a fighting squadron with an all-Norwegian air and ground crew, arrived in England in June, 1941, followed by a third in January 1942. Both of these squadrons fought as part of the British RAF; they participated in the Dieppe Raid, the Normandy landings, and the liberation of Holland.

In the spring of 1942, the leaders of the base invited Sigrid Schultz to visit Little Norway.** They had heard her broadcasts from Berlin about the invasion of Norway and thought she might be interested in doing a story about the camp as the second anniversary of the invasion drew near.

Sigrid spent a week in Toronto, meeting with the young pilots and working on her story. It was easy reporting by her standards: instead of rushing to meet her filing deadline with the details of a breaking story, she could take time to collect material and write the story. She met with the young Norwegians who had escaped from their country to help fight the Germans in a canteen that smelled of fresh cut wood, pine, cleanliness, and a whiff of coffee—scents that perhaps carried with them memories of summer holidays with her cousins in Norway. The young fliers were eager to tell her whatever they knew. She asked each of the men the same question: “What convinced you that you had to leave Norway and come out and fight?” Each had a story of the incident which finally made him decided to risk his life to join the armed forces in exile. Many had thrilling stories of dangerous escapes. The details of each man’s story were different, but the core was the same: the crimes of the Gestapo and the SS convinced them that life in Norway under Nazi rule was not to be tolerated

During her visit, the airmen gave her a parade, passing in review before her while she struggled to hide her tears, perhaps remembering her young Norwegian fiancé who died in the Great War.

As part of her visit, she did a fifteen- minute broadcast from Toronto for the Canadian radio network and Mutual Broadcasting on the second anniversary of the invasion of Norway. Before she spoke, she had to show the text of what she had written to Lieutenant-Colonel Ole Reistadt, the commanding officer of the camp. Speaking to the young men had reminded her about the role neutral Sweden had played in defeat of Norway by allowing Germany to send army supplies through the country. She had been angry then. Now she was angry again. She “made some very nasty remarks about the Swedes” in her script. Reistadt reminded her that neutrality had two sides: “Miss Schultz, you can’t do that because you have a lot of Swedish civilians who help our people escape from the Germans over the mountains. You cannot be nasty to them.” So, she later said with a sigh, “I had to be ladylike.”

Her article ran in the Chicago Tribune on August 16. It was a lively tribute to the young men of the Norwegian air force.

*Actually, in the best of all possible worlds, the Nazis would not have occupied Norway and the question of where to establish an aviation training base would not have arisen.

**Anyone who’s been reading along here for the last several years knows who Sigrid Schultz was. But in case you stumbled on this post while looking for info about Little Norway, here’s the short version: Sigrid Schultz was the Berlin bureau chief for the Chicago Tribune from 1925 to 1941. She was one of the first American reporters to warn her readers just how dangerous the Nazis were and one of the last American reporters to make it out of Berlin.

_______________

It is worth pointing out that the Norwegian merchant marine played a much larger, if less glamorous, role in supporting the Allies in World War II than the Royal Norwegian Air Force. In 1940, Norway had the largest merchant fleet in the world, some 1100 ships. At the time of the Nazi invasion, 1024 of those ships were at sea. King Haakon ordered them to proceed to allied ports. All of them complied. They were then put in the service of the Allies. Norwegian ships carried half the fuel and one third of all other supplies transported to Britain, at great cost to themselves: almost 4,000 seaman killed, some 6,000 additional casualties and 570 ships lost.

August 22, 2024

From the Archives: Last Hope Island

Often when we’re traveling, something we see makes me think about posts from the past, books I’ve read, or posts from the past about books I’ve read.

While we were in Norway, that book/post was Lynne Olsen’s Last Hope Island. As soon as we got home, I pulled it off the shelf and have been dipping in and out ever since. It is just as good as I remembered.

As those of you who hang out regularly here on the Margins have probably guessed, I love it when a book turns what I think I know upside down and shakes the change out of its pockets. Last Hope Island: Britain, Occupied Europe and the Brotherhood that Helped Turn the Tide of War is one of those books.

Historian Lynne Olson looks at the seldom-told stories of how European refugees—both governments-in-exile and individual patriots—continued to fight Nazi Germany from a (relatively) safe base of operations in London.

Taken individually, their stories are dramatic, and occasionally tragic. Queen Wilhemina of the Netherlands was outraged when the captain of the British destroyer on which she escaped Amsterdam refused to put her ashore at Zeeland: she had been determined to “be the last man to fall in the last ditch” in defense of her country. (She continued to be outraged throughout the war. Her grandchildren were not allowed to listen to her radio broadcasts because her language was so bad when she talked about the Nazis) A young French banker named Jacques Allier, traveling on a fake passport, smuggled the world’s supply of heavy water from German-occupied Norway to Scotland under the nose of Abwehr operatives—hamstringing Germany’s efforts to develop a nuclear bomb.

Told in combination, these stories challenge traditional accounts of the war. Olson reminds us that French forces guarded British troops during the heroic evacuation at Dunkirk. That Polish pilots played a critical role in the Battle of Britain and in defending London during the Blitz. That Britain’s successes in breaking the Enigma codes rested on the work of the Polish underground, who were able to decipher a high percentage of Enigma intercepts by early 1938. That Churchill was a butthead as well as a great leader.*

In the English-speaking world, Britain and the United States are often portrayed as standing alone against the Nazis in World War II. Last Hope Island reminds us that was never true.

*Okay. She doesn’t say that. But the stories she tells reinforce my growing dislike for the man.

August 19, 2024

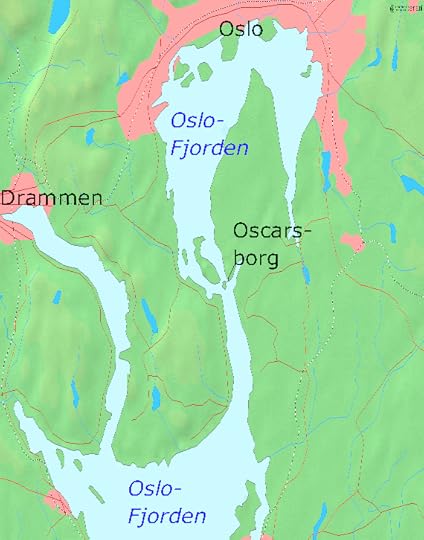

Road Trip Through History: Oscarsborg Fortress and the Nazi Invasion of Norway (plus a little bit about Sigrid Schultz)

As those of you who read my newsletter know,* My Own True Love and I spent two weeks in Norway on a history-nerd tour run by the Vesterheim Museum. We began with Vikings and ended with a tour of the royal palace in Oslo, which was far more interesting than I expected. (As is so often the case when we’re on the road. Never presume.)*** Instead of focusing solely on the decor and its treasures, the docent gave a brief history of the Norwegian royal family. She wove the royal family’s history into the larger history of Norway, nicely wrapping up a number of recurring themes from the last half of the tour. The most important of these was King Haakon VII’s refusal to cooperate with the Nazis and the Norwegian government’s subsequent escape to London.

A history tour of Norway necessarily spends a great deal of time on the Nazi invasion and occupation of Norway. Going in, I had a general sense of the Nazi invasion of Norway, which signaled the end of the and the beginning of action on the Western Front. I was familiar with the story of King Haakon’s heroic stand. But I had forgotten the action at Oscarsborg Fortress which made it possible for the king, the Norwegian government, and members of the Storting (the Norwegian parliament) to escape.

In the early hours of April 9, German troops launched surprise attacks on every major port in Norway. (Though why anyone was surprised is not clear. As Sigrid Schultz reported in her account of the invasion, “Hitler acted according to the pattern so often successful for him: On the one hand, he amazed the world by his swiftness. On the other hand, he gave ample warning of his intention to strike.”)

Norway’s military defenses were shockingly weak, despite the king’s urging that the country re-arm. Despite its strong maritime heritage, the country owned only 70 ships, including the two oldest ironclad ships in the world that were still sailing. (The naval chief of staff called them “my old bathtubs.”) Its army was small, with an elderly officer corps and equally elderly armaments. It had one tank, no submarines, and no anti-aircraft guns. Not surprisingly most of Norway’s military commanders failed to defend their positions. By noon, German forces controlled Narvik, Trondheim, Bergen, Stavanger, Egersund and Kristiansand.

The sole exception was Birger Erickson, the commander of Oscarsborg Fortress. Erickson was scheduled to retire in the fall of 1940. Most of the men under his command were new conscripts who had only been on the island for one week. The fortress itself was no better equipped than the rest of the Norwegian military. Oscarsborg had been the strongest fortress in Europe when it was built in 1855. Norway upgraded the fortress at the end of the nineteenth century, installing new guns (made in Germany) and an underwater torpedo battery. Those “new” weapons were 40 years old when the Nazis attacked Norway. There was no reason to think that Erickson would do any better than his counterparts on the mainland. German intelligence dismissed the fortress and its two antique cannons as obsolete, and was apparently unaware of the torpedo battery.

Obsolete or not, Oscarsborg Fortress was Norway’s last line of defense against the the Germans.

CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index...

A small flotilla of German ships, including a new warship, the Blücher, entered the Oslo fjord shortly before midnight, sailing toward Oslo. In addition to 1500 inexperienced sailors, the Blücher carried German invasion troops, a cadre of government officials, and a military band. Their assignment was to seize the government buildings, including the palace, arrest the royal family, and establish a German administration. The band’s job was to celebrate their success by playing “Deutschland über Alles” in the city center.

The Blücher had to pass the narrows at Oscarsborg Fortress to reach Oslo. Two small island forts fired on the German ship as it sailed up the fjord. Hampered by the fog, they did not hit the ship but their guns warned Erickson that the Blücher was approaching. Shortly before 4 a.m., the ship reached Oscarsborg. The fog lifted as the ship approached. As it came into view, searchlights from the main land illuminated it further and the fortress’s two old cannons, called Moses and Aaron by their crews, fired.**** Both hit their target. Within minutes the ship was on fire. Moments later, the torpedo battery fired, hitting the ship below the water line. Within an hour, the Blücher had sunk. More than 1000 men were lost, including the government officials who had been tasked with setting up the Nazi administration in Oslo. Only a few hundred men escaped

The remainder of the small invasion fleet retreated.

The actions of the men at Oscarsborg Fortress did not stop the Germans from taking Norway, but they delayed the invasion of Oslo and the establishment of a viable Nazi government long enough for the royal family and key members of the government to escape. It also gave the Bank of Norway time to ship out fifty tons of gold bullion that the Nazis had planned to seize.

* It’s time for my occasional reminder that in addition to History in the Margins, I also write a semi-monthly newsletter. With a very few exceptions, this blog and the newsletter have completely different material. In the newsletter, I struggle with historical concepts rather than telling historical stories and share my experience of the process of writing. In recent issues, I’ve considered a special case of active vs. passive voice, talked about the new-to-me concept of experimental archeology, and looked at the bigger themes of our multi-year road trip down the Great River Road.** If that sounds like your piece of cherry pie, you can subscribe here.

** I’ve shared stories of our adventures driving along the Mississippi over the last ten (!!!) years here on the Margins. We drove the last stretch in May, and there are stories yet to come. As you may have noticed, I’ve been busy for the last couple of months.

***One unexpected high point: when we were in the ballroom, the docent suggested that guests take a spin . After all, we might never have a chance to dance in a royal ballroom again. My Own True Love offered me his arm and we waltzed across the room. Big Fun! Also, swoon!

****Our guide was quick to point out the irony of cannons named after iconic Jewish historical figures taking out a Nazi warship.

August 15, 2024

Building Blocks

I’ve lived in Chicago since the fall of 1980, but I never noticed that the street side of the Tribune Tower is embedded with stones from famous buildings around the world until recently. The trigger for me was correspondence from Sigrid Schultz detailing her successes and failures in acquiring, authenticating, and shipping stones to the Tribune’s Chicago office from a variety of locations, including Wartburg Castle, where Luther lived in hiding for a time.

The project was a brainstorm of the paper’s owner, Colonel Robert McCormick—one of many that he would inflict on his foreign correspondents over the years.

Among other things, McCormick was a history bugg* and collector of historical memorabilia on a grand scale. He acquired what would be the first pieces of the Tribune Tower collection on a brief stint as a war correspondent in 1914. While touring the trenches in France, he pocketed stones from the medieval cathedral of Ypres, which had been damaged by German shelling, and a historic building in Arras.

When McCormick began constructing his Tower in 1923, he decided to expand his collection of historical rocks and incorporate them into the structure of the building. He sent a memo to his foreign correspondents instructing them to acquire “stones about six inches square from such buildings as the Law Courts of Dublin, the Parthenon at Athens, St. Sophia Cathedral, or any other famous cathedral or palace or ruin—perhaps a piece of one of the pyramids” and send them to Chicago.

Not surprisingly, local authorities were not always happy to supply the Colonel with a piece of their historical landmarks. Nonetheless, Tribuners successfully collected 136 stones from sites near and far. After the Colonel’s death in 1955, his successors decided to continue the tradition, adding a moon rock in 1971 and a piece of the Berlin wall in 1990.

*A typo that I accept whenever I commit it. I honestly think it makes as much sense as history buff. If the Oxford English Dictionary is to be believed, the use of buff to describe a fan of any sort is an extension of a person who was fascinated by fires and firemen. They were called “buffs” in the early twentieth century because of the buff-colored uniforms then worn by volunteer firemen in New York. Who knew?

_____

For those of you who might be interested, I will be talking about Sigrid Schultz on the History Happy Hour podcast on Sunday, August 18 at 3pm central time. You can watch it in real time here: https://www.facebook.com/events/1514126705853093 or here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hJ1eErYSE6E. It will also be available for streaming later.

August 12, 2024

Reporting from Weimar Berlin: More Than Just the Nazis

Last Saturday, I spoke about The Dragon From Chicago to an enthusiastic audience at History Camp 2004 in Boston.* At the end, a member of the audience stopped me and asked if Sigrid Schultz reported on anything besides politics.

The short answer is yes, indeed she did. In fact, at one point, Joseph Pierson, then managing editor of the Chicago Tribune, felt the need to remind Sigrid that “Public interest in stories involving scientific progress and adventure is much more constant and reliable than its interest in the long-winded maneuvers of international politics.”

Foreign bureaus didn’t just cover the “big news” Sigrid was expected to report on American visitors in Berlinm especially visitors from Chicago, on advances in science and technology, huyman interest stories, the escapades of Europe royalty, and the arts. Aviation-related stories were particularly popular, because Americans (including the Tribune’s owner Colonel McCormick) were aviation mad, even before Lindburgh’s flight across the Atlantic took over front pages everywhere in May 1927. Sigrid reported many, many aviation stories. In fact, she almost managed to be a passenger on the first Zeppelin passenger flight from Germany to the United States. She was thrilled with the idea, but ultimately the Tribune decided the story didn’t justify the cost of the ticket. Schultz was not pleased. Especially when Lady Hay Drummond-Hay had the distinction of being the only woman on the flight.

At various times Sigrid reported on the opening of direct telephone service from Berlin to Chicago,** royal marriages and misalliances, and the hunt for and status of America’s most notorious World War I draft dodger, Grover Cleveland Bergdoll, whose appearances and disappearances were a regular feature of Sigrid’s “mail stories” in the 1920s and 1930s. ***

In short, Nazis were the big story of her career, but they weren’t the only story.

*For those of you who don’t know, History Camp is a day-long extravaganza for history nerds of all kinds. 50 speakers. 350 attendees. Lots of programs. Many badges simply listed their wearers as history enthusiasts. Rumor has it that they will post videos of the sessions on the website down the road. In the meantime, if you’re interested, here’s the link to my podcast episode on History Camp Author Discussion: https://historycamp.org/pamela-d-toler-the-dragon-from-chicago-the-untold-story-of-an-american-reporter-in-nazi-germany/

**It was a big deal and the story made the front page. Previously calls had to connect through Paris. Sigrid called in the story on February 10, 1928, as the dateline proudly noted, by trans-Atlantic telephone from the Berlin office of the Tribune. She pointed out to her readers that in Berlin night was falling and the street lamps were lit, though she knew it was midday in Chicago: “Science at last enables my voice to conquer time and space.”

***America’s fascination with celebrities, the wealthy, and especially wealthy celebrities, behaving badly is nothing new. Grover Cleveland Bergdoll–wealthy playboy, early aviator, race car driver, and draft doodger–checked all the boxes.

August 9, 2024

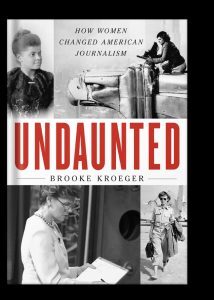

More Stories of Women Journalists

I’ve heard from a number of you that you enjoyed the stories of women foreign correspondents that I posted over the last two months. Some of you shared your own experiences as journalists in the 1970s and 1980s–remarkably similar to those of women reporters in the 1930s and 1940s, alas. More than one of you suggested that any one of the women whose stories I shared would be worth a book in her own right.*. Since so many of you were interested, I think it is time to share a book that I think many of you will enjoy.

Undaunted: How Women Changed American Journalism by Brooke Kroeger is not an encyclopedic listing of women journalists over the last 180 years.** Instead, it is, using her own word, a representative account of women who held meaningful positions in American newsrooms, beginning with Margaret Fuller in the 1840s and ending with the reporters who launched the #MeToo movement with their investigative reporting in the early 2020s. The book is full of intriguing accomplished women, many of whom are largely forgotten. More importantly, it traces what Kroeger describes as a recurring theme that continues into the modern day of “progress followed by setback.”

The book is fascinating, occasionally infuriating (because of the subject, not because of Kroeger’s writing), and overall a delight to read. If you’re interested in women’s history, journalism or, obviously, women journalists, this one’s for you.

*That might be true, but I won’t be the one writing those books. Even if the sources exist, which may not be the case, I’m ready to move on from journalists to something else. I don’t know what, but I most likely will be writing about a tough broad whom we need to know more about.

**And a good thing, too. Such books, whether they look at women journalists or women warriors, are useful, but not much fun to read.

August 5, 2024

It’s Publication Day for The Dragon From Chicago!

On May 8, 2020, I announced here on the Margins, after months of hinting, that I had a contract with Beacon Press for a new book about Sigrid Schultz, Berlin bureau chief for the Chicago Tribune. I expected to finish the book in two years. *Cue manic laughter*

Four years and a bit later, The Dragon from Chicago is finally out in the world.*

I’ve spent the last four years deep in the world of foreign correspondents, American newspapers. Weimar Germany, “false news,” glass ceilings, American isolationism, Nazis, the Lost Generation, the rise of radio news, daily life in Berlin, and the challenges of getting the news out in the face of tightening controls over the press. I’ve learned a lot in the process, and I’ve tried to share it with you every step of the way, from big stories like the rise of the Weimar Republic to small ones, like my realization that Oscar Mayer, of wiener fame, was a real human being.

Thanks for your support and encouragement along the way. It kept me going on the days when I wasn’t sure anyone would care.

You’ve already received the information that I’m throwing an on-line launch celebration tonight**, in conversation of Olivia Meikle, co-host of the What’s Her Name Podcast. If you’ve already signed-up, you’ll get the Zoom link today. (It may already be in your in-box.) If you didn’t sign up and wish you had, here’s the link:

Join Zoom Meeting

https://us06web.zoom.us/j/87516374458?pwd=UGaOsk76MUIm5PcMF8JtuBN4muZgsa.1

Meeting ID: 875 1637 4458

Passcode: Party

Starting Friday, we’ll be back to business as usual here on the Margins, with some stories that didn’t make it into the book, some Road Trip Through History adventures, and reviews of books that I hope you’ll enjoy as much as I have. There’s never a lack of history to share!

*If you literally see it out in the world, take a picture and share it with me! Or better yet, share it in your social media feeds.

**Assuming you’re reading this on August 6

July 29, 2024

One Final Woman War Correspondent: Helen Kirkpatrick

American reporter Helen Kirkpatrick (1909-1997) had already spend five years as a foreign correspondent in Europe when America entered World War II.

She had stumbled into reporting in1 935. After a summer job escorting 30 teenage girls around Europe, she cabled her husband that she wasn’t coming back and found a job with the Foreign Policy Association in Geneva. The FPA was located near the press room in the League of Nation’s building. She not only made friends with reporters, she began covering for them when needed. After a time, the European office of the New York Herald Tribune offer her a job as a stringer with a regular, though very small, salary. She jumped at it.

In 1937, she moved to London, where she worked as a freelance contributor for a number of newspapers. During the Munich Crisis, she was a temporary diplomatic correspondent for the Sunday Times.

During her time in London, she published a weekly newsletter, along with Victor Gordon-Lennox of the Daily Telegraph and Graham Hutton of the Economist. Titled Whitehall News, it campaigned against the British government’s policy of appeasing dictators: Winston Churchill, Anthony Eden, and the King of Sweden were all subscribers. (I assume Neville “Peace in our time” Chamberlain was not.)

Shortly before the war she joined the London office of the Chicago Daily News, the owner of which had previously refused to hire women staff writers. Her first assignment was to get an interview with the Duke of Windsor, who was well known not to give interviews.* Despite the scoffing of her male colleagues, she was able to get a meeting with the former king. He reiterated that he did not give interviews, but saw no reason that he couldn’t interview her. That reverse interview was her first by-lined story in the paper

Kirkpatrick worked for the Chicago Daily News throughout the war. She wrote about the London Blitz, covered the arrival of the first troops of the American Expeditionary Force in Ireland, and spent six months reporting on the North African campaign in 1943, including the surrender of the Italian fleet at Malta. After D-Day, she became the first correspondent assigned to the Free French headquarters in Europe. She entered Paris on August 25 1944 riding in a tank with General Leclerc’s 2nd armored division. Her final wartime assignment was a trip to Hitler’s mountain retreat at Berchtesgaden—almost a required stop for American correspondents at the end of the war.

She was the only woman correspondent who received medals of valor from both the United States and the French governments for her war coverage.

She continued to work as a foreign correspondent for a few years after the war—working for the New York Post, which had taken over the Chicago Daily News. She then moved into the public sector, first as an information officer for the Marshall Plan office in Paris and then as the Public Affairs Office for the Western European Division of the State Department.

She gave up her career when she married Robbins Milbank in 1954. Not an unusual decision at the time, though a loss to journalism.

*This sounds to me like someone was setting her up to fail.

***

One short week until The Dragon From Chicago hits bookstore shelves. Am I excited? Darn tootin’ I’m excited!

Heads up to my Chicago people: The event on August 6 at City Lit Books has been cancelled.

July 25, 2024

Ann Stringer: The Widow on the War Front

Ann Stringer (1918-1990) was a reporter for the United Press before the beginning of World War II. She had reported alongside her husband, Bill Stringer, from Dallas, Columbus, and New York and as foreign correspondents in Latin America. By 1944, both of them were eager to be reassigned to Europe, where the real action was. They struck a deal with Reuters. Not surprisingly, Bill got his accreditation as a war correspondent first.* The plan was that Ann would follow as soon as her accreditation came through.

The day Ann was scheduled to leave for Europe, she learned that Bill had died in Normandy.

She was even more determined to get to the war front and cover the big stories. She sailed for England in late 1944 as an accredited war correspondent with the United Press. She filed her first story from London in January, 1945, then moved to the First Army press camp, where Bill had been assigned. According to Andy Rooney,** when Ann replaced Bill Stringer on the job “the rest of us in the First Army press camp didn’t know how to act toward her. Ann made it easy. She just picked up and did Bill s job, often with tears in her eyes.”

As is so often the case when a widow steps into her husband’s field boots, Ann exceeded expectations. And her colleagues at the United Press did not hesitation to admit it. According to Walter Cronkite, “She was tough. She knew what she wanted, and she knew how to get it. And she was one of the best reporters I have ever known. And, yes, she was beautiful.” Harrison Salisbury took his praise even further: “What I can tell you about her is that she was simply superb, the best man (I’ll say that even if it sounds chauvinistic) on the staff. Annie illuminated every one of her assignments. She was all reporter–not ‘girl reporter’—straight reporter. She was a two-fisted competitor.”

Stringer often ignored the Army’s restrictions on women in the front and was warned at least once that refusal to comply would lead to the loss of her accreditation. She learned to file her stories with vague datelines that wouldn’t trigger questions at army headquarters. When she couldn’t get official jeep transportation to the combat zone, she begged unofficial rides, including a lift over the bridge at Remagen from a general in a tank.

She is best known for sending the first dispatch reporting the link-up between the American and Soviet armies at Torgau, Germany, on the Elbe River, on April 26. She persuaded a friend in Army Intelligence to lend her and an INS photographer two small spotter planes and the pilots to fly them to Torgau. After an hour in Torgau, carrying her typewriter and a roll of film, she hitched a ride to Paris on a C-47 cargo plane and scooped her competitors/colleagues.***

Ann continued to report from Europe through the summer of 1945 and later covered the Nuremberg trials. In 1949, she left United Press, married German-born American photographer Hank Ries, and settled in Manhattan, where she continued to write for a variety of news media.

*Even before 1944, when the United States put regulations in place distinguishing between male and female correspondents, there were always limitations on women, even if they were “written in invisible ink” as photojournalist Margaret Bourke-White put it.

**Yes, that Andy Rooney. Even crotchety old icons were once bright-eyed young reporters. (Or maybe he was a crotchety young reporter. I don’t know for sure.)

***Other correspondents were always both.

***

Twelve days until the publication of The Dragon From Chicago! So. Dang. Excited.