Pamela D. Toler's Blog, page 17

June 20, 2024

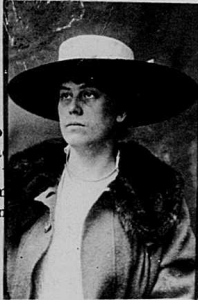

Dorothy Fuldheim: An Exception to (All) The Rules

Women reporters faced a new kind of journalism after World War II. The long-standing prejudice against women newscasters in radio* was even more pronounced in the newly developing world of television—and would remain so for decades.**

There is always an exception.

Dorothy Fuldheim (1893-1989), a retired schoolteacher who was born the same year as Sigrid Schultz, broke all the rules about women on television. After several years of working on air for a local radio station she became the first news anchor on Cleveland’s first commercial television station WEWS in 1947 at the age of 54. Ten year later, she handed over the anchor job to others and became the host of a popular afternoon interview program. Her guests included John, Robert and Ted Kennedy, the Duke of Windsor, historian Arnold Toynbee, Madame Chaing Kai-Shek, Willy Brand, Helen Keller and Muhammad Ali. WEWS also used her as a roving foreign correspondent. She won an award from the National Overseas Press Club for an interview she did with in Hong Kong with two American prisoners released by Communist China in 1955.

Fuldheim found herself at the center of controversy in 1971 when she denounced the Kent State shootings as murder on the air. “ And who gave the National Guard the bullets?” she demanded, tears streaming down her face. “ Who ordered the use of them? Since when do we shoot our own children?” The station received hundreds of calls and thousands of letters from listeners who thought the Guard action was right. Fuldheim offered to resign. WEWS kept her on the air.

Fuldheim finally gave up the show when she suffered the first of two strokes at the age of 91. Speaking after Fuldheim’s death in 1989, Barbara Walters called her “the first woman to be taken seriously doing the news.”

*Network officials believed Americans had no objection to hearing women read ads or discuss“women’s issues.” (By which they meant recipes, housework, fashion, and childcare, not the barriers to entry that limited women’s access to education, jobs, and political office.) Those same officials were sure audiences did not want to hear a female voice deliver the news. Because. Stayed tuned in coming weeks for the stories of women who made it on the air despite those objections.

**If you’re interested in the history of women on television, I strongly recommend Cynthia Bemis Abrams’ podcast/blog Advanced TV Herstory

My publisher is giving away 25 copies of The Dragon From Chicago on Goodreads. You can sign up here through July 4. Good luck!

June 17, 2024

Madame Geneviève Tabouis: A French Thorn in Hitler’s Side

I first came across French columnist Geneviève Tabouis in a letter from Sigrid Schultz, to the Chicago Tribune’s owner and publisher Robert McCormick written on May 17, 1939,* in which she outlined Hitler’s plans for a Nazi-controlled Europe. After outlining how Hitler intended to divide up Europe, she told McCormick “Friends of mine were present when Hitler explained to them how he plans to ‘force England on her knees’ should she try to prevent Germany from taking the land Hitler claims for his people. It sounds phantasmic, yet I feel it my duty to write to you about this. My source has always proved absolutely trustworthy and what seemed phantasmic to us became hard reality much quicker than even Hitler’s aides expected.”

Hitler’s plans for scaring the British into agreeing with his demands included the air bombardment of London. Schultz admitted that she wasn’t the first reporter to have heard about Hitler’s air bombardment plan: “One of the Paris ‘sensation mongers’, Madame Tabouis, wrote about this bombardment plan against London. She was branded insane. I did not believe it myself, but I now know that Hitler has repeatedly spoken to his closest aides along these lines.”

I was curious to learn more about this “sensation monger” who had beaten Sigrid to the punch with her “insane” prediction. It was rabbit hole time.

Tabouis was born on February 23, 1892—eleven months prior to Schultz—and like Schultz she was the daughter of an artist. (Her relatives on her mother’s side were French diplomats and senior military officers.) After brief periods in which she raised silkworms and kept a frog, she became obsessed with history and poetry. She studied at the Sorbonne for three years. (I can’t help but wonder if she and Sigrid crossed paths there given their shared interest in history.) She then attended the school of archaeology at the Louvre. (Somewhat earlier than Christiane Desroches-Noblecourt.) She was particularly interested in Egypt and was proud when she had learned enough hieroglyphics to use them to write a letter to her favorite dance partner.**

Her life took a turn away from ancient history during World War I. *** She was married in 1916 and had two small children thereafter. During this period, she became fascinated by politics and attended political debates in the French Chamber of Deputies the way some women went to afternoon matinees. Her uncle, French diplomat Jules Cambon, recognized writing talent in her letters. With his encouragement, and access to his circle of contacts, she began to write short, amusing articles about people and events for two provincial newspapers.

In the 1930s, Tabouis became first a columnist for L’Oeuvre, a popular left-wing French paper and later its foreign news editor. Her columns were chatty, engaging, and smart. They were soon syndicated throughout Europe.

Tabouis was one of the first French journalists to speak out against Hitler and the Nazis. For week after week through the 1930s, she turned out columns in which she reported on Hitler’s political moves, speculated on his motives, and predicted his actions with uncanny accuracy. Her columns regular sent him into rages; her predictions occasionally disrupted his plans.

She fled Paris shortly before the German army arrived and took asylum in the United States. She was tried for treason in absentia.

In New York, Tarbois wrote for the Daily Mirror and founded a weekly French-language magazine, Pour La Victoire, which run through the war. After the war, she returned to France , where she was honored as an Officier de la Légion d’honneur and Commandeur de l’order national du Mérite. After her death, she was lauded as the “doyenne of French journalists.”

*Several months before Germany marched into Poland and triggered World War II.

**Which makes me wonder whether he was able to read it. My sources don’t say. And perhaps that wasn’t the point.

***She picked the topic back up after the war. At the same time that she was building a career as an influential journalist, Tarbouis wrote and published popular biographies of Tutankhamen (1929), Nebuchdnezzar (1931), and Solomon (1936) as well as three books on contemporary politics and diplomacy. She once told her readers that she couldn’t remember an evening when she hadn’t worked, including weekends and Christmas. Her only form of relaxation was playing with her cats.

My publisher is giving away 25 copies of The Dragon From Chicago on Goodreads. You can sign up here through July 4. Good luck!

June 13, 2024

May Craig: “Tough as a Lobster”

May Craig (1889-1975) spent most of her career as the Washington correspondent for the Maine-based Gannet newspaper chain. She provided her Maine readers with a keen-eyed and sharp-tongued look at the nation’s capital in her “Inside Washington” column for some forty years.

She was the first woman to attend Franklin Roosevelt’s press briefings, an original member of Eleanor Roosevelt’s Press Circle, a weekly press conference that was only open to women journalists,* and a regular at presidential press briefings from Truman to Johnson. A colleague once described her as “the Washington press gallery nemesis of all evasive politicians.” She was a frequent panelist on Meet the Press. She always wore a hat and gloves on the program. She said it was so that people would remember who she was, as if her pointed and relentless questioning wasn’t enough to make her memorable

As a war correspondent during WWII, she reported on V-bomb raids in London, the Battle of Normandy, and the liberation of Paris, but her primary focus was the experience of Maine’s G.I’s in the European theater.

Throughout her career, she fought to open doors for women reporters, including getting a women’s bathroom installed outside the congressional press galley. Her most important accomplishment for women’s rights was the “May Craig Amendment”, prohibiting employment discrimination on the basis of sex, which became federal law as part of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. Reminiscing late in her career, she said that “Bloody Mary of England once said that when she died they would find `Calais’ graven on her heart.** When I die, there will be the word `facilities,’ so often it has been used to prevent me from doing what men reporters could do.”***

*The press circle gave women journalists access to news and helped save many of their jobs at a time when newspapers were cutting reporters: if newspapers wanted to cover Eleanor they had to hire women reporters. According to Eleanor, the intention was that the conferences would cover subjects of special interest to women and would avoid what she described as “my husband’s side of the news.” They also gave her an unprecedented national platform.

**A reference to the loss of Calais, England’s last continental possession, during Mary Tudor’s reign. The city had been under England’s control since 1347 and was the main port through which English wool was exported.

***In World War II, the United States military did not allow women journalists to travel closer to the front than women service members, which effectively meant field hospitals with nursing detachments. The military justified the policy in terms of the difficulty of providing housing and latrine facilities. (A similar concern fueled regulations against allowing women in combat.)

And lest you think the question of facilities was limited to the battlefield, I offer you this blog post by author Nancy B. Kennedy on the facilities problems suffered by women members of Congress: “Democracy Demands a Pair of Pants.”

My publisher is giving away 25 copies of The Dragon From Chicago on Goodreads. You can sign up here through July 4. Good luck!

June 10, 2024

A different path to being a war correspondent aka the woman on the spot

The Great War provided new opportunities for women journalists.*

No women received official press accreditation with the American Expeditionary Force (AEF) during World War I, but a number of female journalists reached the front as “visiting correspondents.” Soon after the war began, the Saturday Evening Post, which had the largest circulation of any American magazine at the time, sent popular novelists Cora Harris and Mary Roberts Rinehart to Europe as reporters. (Rinehart was the first journalist to visit the frontline trenches.) Freelancers, veteran newspaperwomen, reporters for women’s magazines like Good Housekeeping and Ladies’ Home Journal, and journalists with assignments from general interest magazines, like Scribner’s and Collier’s, followed in their footsteps.

At the same time, two women who were already reporting from Europe, May Birkhead of the New York Herald and Carolyn Wilson of the Chicago Tribune, added war correspondent to their job description. Both wrote society and fashion news from Paris before the war.**

Birkhead, a seamstress who stumbled into a thirty-year career as a journalist with a firsthand account of the sinking of the Titanic, wrote feature stories about the war and later reported on the Versailles peace conference. She earned a commendation from General John Pershing for her work.

Wilson, who continued to write her illustrated fashion column throughout the war, filed thoughtful political analyses, human interest stories about American soldiers in the trenches, and reported pieces from both sides of the front. The Tribune described her war reporting as “the news of the battle front as a woman sees it.” She became the subject of the news rather than a reporter in 1915, when she was briefly imprisoned in Berlin on suspicion of espionage.

(To my surprise, another Chicago Tribune reporter followed Carolyn Wilson’s path in World War II, though with somewhat less verve. Anne Bruyere, like Birkhead and Wilson, was a fashion reporter in Paris when the war broke out. While she did not make it to the front, she reported on conditions in occupied Paris and later on the experiences of American soldiers, WACS, and Red Cross volunteers in liberated Paris—all the while reporting on French fashion.)

*If you want to dive more deeply into this topic, I highly recommend Chris Dubbs’ An Unladylike Profession: American Women War Correspondents in World War I

**This type of writing is a type of foreign correspondence in its own right though it is seldom treated as such, precisely because it was aimed at women and therefore not to be taken seriously

My publisher is giving away 25 copies of The Dragon From Chicago on Goodreads. You can sign up here through July 4. Good luck!

June 6, 2024

Anne O’Hare McCormick: “Freedom Reporter”

Like Sigrid Schultz, Anne O’Hara McCormick (1880-1954) became a foreign correspondent because she was in the right place at the right time.

She already had experience as a journalist before she became a foreign correspondent. After her graduation from a private Catholic high school in 1898, she went to work for the Catholic Universe Bulletin in Cleveland, Ohio, , where she rose to the position of assistant editor.

In 1910, at the age of thirty, she married Francis J McCormick. Francis was a wealthy engineer who imported large equipment based in Dayton Ohio who traveled extensively in Europe for his job. Anne went with him.*

Like other working women of the period, Anne left her job when she got married,** but she continued to write occasional pieces on a freelance basis which appeared in magazines like Catholic World, Atlantic Monthly, and The Saturday Evening Post. In 1921, after a piece of hers titled “New Italy of the Italians” ran in the New York Times Book Review and Magazine, Anne, wrote to Carl Van Anda, managing editor of the Times, asking if she could write news stories for him from Europe. His answer: Try it.

Try it she did. Her first regular by-lined article appeared in the Times in February 1921: a piece about Sinn Fein titled “Ireland’s ‘Black and Tans’.” Anne soon became a regular freelance correspondent for the Times. (The paper’s publisher, Adolph Ochs, refused to hire women as staff correspondents.) Her lack of a staff position proved to be a blessing of sorts, Unlike staff foreign correspondents, who were assigned to a specific location, Anne was free to travel as dictated by her interests, or Francis’s business assignments.

Small, matronly, soft spoken and charming, Anne used her networking skills get interviews with any one who mattered, including Chamberlain, Hitler, Mussolini, and Roosevelt—even without the credentials of a staff correspondent. She occasionally covered a breaking news item, but for the most part she wrote in-depth think pieces for the Times‘ magazine that ranged in subject from political analysis—she was one of the first to predict Mussolini’s rise to power—to a comparison of street lighting in different European cities and what the differences said about them. She wrote stories about developments in the United States as well as in Europe, most notably pieces on the Florida real estate boom in 1925 and the “New South” in 1930.

In 1936, after Ochs’ death, his successor made her a full-time salaried “freedom reporter.” Her assignment was to travel the world and write three world affairs columns each week, reporting on conditions in places where she believed freedom was threatened. He also made her a member of the Times’ editorial board, a position she held until her death in 1954.

In 1937, she became the first woman to receive the Pulitzer Prize for journalism for her dispatches and feature articles from Europe.***

She continued to report from abroad after the United States entered World War II. When the war ended, she served as a UNESCO delegate in 1946 and 1948.

*I spend a lot of time considering whether or not to call the subjects of my work by their first name. In the case of Sigrid Schultz, I chose to use her last name once she was an adult because I was uncomfortable first-naming her while I called her male colleagues by their last names. Since there are two McCormicks here, I have opted for Anne and, to the extent that he appears, Francis.

**Often they didn’t have a choice. Many employers refused to allow married women to remain on the job. (As I have pointed out before, this did not apply to women working as household servants or other working class jobs. It is all too easy to view the history of women at work through the lens of the middle and upper class experience.)

***She was not, however, the first woman to win a Pulitzer. That honor belongs to two sisters, Laura Elizabeth Richards and Maude Howe Elliott, who collaborated on a biography of their mother, Julia Ward Howe. They were awarded the very first Pulitzer in biography in 1917.

My publisher is giving away 25 copies of The Dragon From Chicago on Goodreads. You can sign up here through July 4. Good luck!

June 3, 2024

Lady Florence Dixie, the First Woman War Correspondent. Sort of.

For the next two months, as the launch date for The Dragon From Chicago (1) hurdles toward me, it’s going to be women journalists all the time here on the Margins. (It is perhaps not surprising that I “met” a number of them over the last four years.)

First up, Scottish writer, traveler and feminist Lady Florence Dixie (1855-1905)

Lady Florence Dixie first came to my attention while I was reading Candice Millard’s Hero of the Empire. Millard mentioned in passing that Dixie was the first woman war correspondent. I had a “wait, what?” moment. But I was deep in the throes of writing The Dragon From Chicago and I resisted the temptation to go down the research rabbit hole. (2)

Once I had a moment to circle back I learned that Dixie’s stint as a war correspondent was only a small incident in an event-filled life.

After a tumultuous childhood, (3) the 19-year-old Lady Florence married Sir Alexander Beaumont Churchill Dixie, known as “Sir A.B.C.D.” or Beau. They shared a love of adventure and the outdoors. Their travels together provided Dixie with material for several of her books. (4)

Although Dixie wrote popular novels for adults and children, many of which dealt with women and girls and their positions in society, she is best known for her bestselling travel books, Across Patagonia (1880) and In the Land of Misfortune (1882). Like her better known counterparts, Isabella Bird and Mary Kingsley, she presented herself as the protagonist of the stories in which documented her travels. (5)

In Across Patagonia, she told the story of her 1878 trip to Patagonia, with her husband, her brothers, and their friend Julius Beerbohm. They traveled some 1000 kilometers on horseback over a period of 60 days. In her account of the expedition, Dixie appears as a heroic adventurer, who meets the trials of the road with resilience: as she describes it she (and her companions) were “nearly starved…almost smothered in a pampas fire, badly shaken by earthquakes, forced to wade knee deep through rivers and sleep in the open with a saddle for a pillow.” She not only holds her own with her male companions in physical terms, she also takes on Charles Darwin on the intellectual plan. Darwin had claimed that the Tuco-tuco of Patagonia were nocturnal animals that lived almost entirely underground. Lady Florence had observed the small rodents in daylight hours, and wrote Darwin to tell him so. She later sent Darwin a copy of her book, in which she described her observations.

Dixie’s account of her Patagonia adventures, inspired Algernon Borthwick, the editor and owner of the Morning Post of London to hire her in 1881 to report on the First Boer War. When she landed in Cape Town, she learned that the war was over. Her first dispatch reported details of the peace treaty.

Dixie spent the next six months traveling through South Africa with Beau and reporting on the causes and consequences of the conflict. She described later her experiences in Africa in In the Land of Misfortune and A Defence of Zululand and its King.

In addition to her work as an author, Dixie was an active proponent of women’s equality. She advocated not only for women’s suffrage but for changes in marriage and divorce laws and the rules governing succession to the British crown. An enthusiastic sportswoman, she was the first president and an active promoter of the British Ladies Football Club

(1) You’ve heard it before: The Dragon from Chicago is available for pre-order wherever you buy your books. Unless you buy books solely at used bookstores and library sales. (No judgement. I’ve been known to come away with armloads of books from both.) If you want a signed copy, you can get one from my local independent bookstore: https://www.semcoop.com/dragon-chicago-untold-story-american-reporter-nazi-germany . Be sure to requested a signed copy, with details about how you want it signed, in the special instructions box. (Because several people have asked: they ship.)

(2) Something I seldom manage. In this case, I trusted that Candice Millard knew whereof she spoke and that Lady Florence would be available when I had more time.

(3) Among other things, she and two of her siblings were the subject of a child custody case between her mother, who was the widow of the 9th Marquess of Queensbury, and the children’s legal guardians after Lady Queensbury converted to Catholicism.

(4) Due to Beau’s drinking and gambling problems, the couple were sometimes referred to as “Sir Always and Lady Sometimes Tipsy.” Despite the lightheartedness of the nickname, Beau’s gambling added an element of financial insecurity to their lives that may have made her writing more than an engrossing hobby.

(5) I am shocked to realize that I have never written about the phenomenon of Victorian women travel writers. It is a fascinating and complicated subject. As a group, their works reject Victorian mores as applied to themselves but fail to examine the underlying racist and imperialist ideas of their times. With any luck I’ll circle back to this subject come the fall.

Lady Florence Dixie, the Frist Woman War Correspondent. Sort of.

For the next two months, as the launch date for The Dragon From Chicago (1) hurdles toward me, it’s going to be women journalists all the time here on the Margins. (It is perhaps not surprising that I “met” a number of them over the last four years.)

First up, Scottish writer, traveler and feminist Lady Florence Dixie (1855-1905)

Lady Florence Dixie first came to my attention while I was reading Candice Millard’s Hero of the Empire. Millard mentioned in passing that Dixie was the first woman war correspondent. I had a “wait, what?” moment. But I was deep in the throes of writing The Dragon From Chicago and I resisted the temptation to go down the research rabbit hole. (2)

Once I had a moment to circle back I learned that Dixie’s stint as a war correspondent was only a small incident in an event-filled life.

After a tumultuous childhood, (3) the 19-year-old Lady Florence married Sir Alexander Beaumont Churchill Dixie, known as “Sir A.B.C.D.” or Beau. They shared a love of adventure and the outdoors. Their travels together provided Dixie with material for several of her books. (4)

Although Dixie wrote popular novels for adults and children, many of which dealt with women and girls and their positions in society, she is best known for her bestselling travel books, Across Patagonia (1880) and In the Land of Misfortune (1882). Like her better known counterparts, Isabella Bird and Mary Kingsley, she presented herself as the protagonist of the stories in which documented her travels. (5)

In Across Patagonia, she told the story of her 1878 trip to Patagonia, with her husband, her brothers, and their friend Julius Beerbohm. They traveled some 1000 kilometers on horseback over a period of 60 days. In her account of the expedition, Dixie appears as a heroic adventurer, who meets the trials of the road with resilience: as she describes it she (and her companions) were “nearly starved…almost smothered in a pampas fire, badly shaken by earthquakes, forced to wade knee deep through rivers and sleep in the open with a saddle for a pillow.” She not only holds her own with her male companions in physical terms, she also takes on Charles Darwin on the intellectual plan. Darwin had claimed that the Tuco-tuco of Patagonia were nocturnal animals that lived almost entirely underground. Lady Florence had observed the small rodents in daylight hours, and wrote Darwin to tell him so. She later sent Darwin a copy of her book, in which she described her observations.

Dixie’s account of her Patagonia adventures, inspired Algernon Borthwick, the editor and owner of the Morning Post of London to hire her in 1881 to report on the First Boer War. When she landed in Cape Town, she learned that the war was over. Her first dispatch reported details of the peace treaty.

Dixie spent the next six months traveling through South Africa with Beau and reporting on the causes and consequences of the conflict. She described later her experiences in Africa in In the Land of Misfortune and A Defence of Zululand and its King.

In addition to her work as an author, Dixie was an active proponent of women’s equality. She advocated not only for women’s suffrage but for changes in marriage and divorce laws and the rules governing succession to the British crown. An enthusiastic sportswoman, she was the first president and an active promoter of the British Ladies Football Club

(1) You’ve heard it before: The Dragon from Chicago is available for pre-order wherever you buy your books. Unless you buy books solely at used bookstores and library sales. (No judgement. I’ve been known to come away with armloads of books from both.) If you want a signed copy, you can get one from my local independent bookstore: https://www.semcoop.com/dragon-chicago-untold-story-american-reporter-nazi-germany . Be sure to requested a signed copy, with details about how you want it signed, in the special instructions box. (Because several people have asked: they ship.)

(2) Something I seldom manage. In this case, I trusted that Candice Millard knew whereof she spoke and that Lady Florence would be available when I had more time.

(3) Among other things, she and two of her siblings were the subject of a child custody case between her mother, who was the widow of the 9th Marquess of Queensbury, and the children’s legal guardians after Lady Queensbury converted to Catholicism.

(4) Due to Beau’s drinking and gambling problems, the couple were sometimes referred to as “Sir Always and Lady Sometimes Tipsy.” Despite the lightheartedness of the nickname, Beau’s gambling added an element of financial insecurity to their lives that may have made her writing more than an engrossing hobby.

(5) I am shocked to realize that I have never written about the phenomenon of Victorian women travel writers. It is a fascinating and complicated subject. As a group, their works reject Victorian mores as applied to themselves but fail to examine the underlying racist and imperialist ideas of their times. With any luck I’ll circle back to this subject come the fall.

May 30, 2024

From the Archives: Daughters of Chivalry

In Daughters of Chivalry: The Forgotten Princesses of King Edward Longshanks, historian Kelcey Wilson-Lee tells the stories of the five daughters of Edward I of England and his first wife, Eleanor of Castile, who survived into adulthood: Eleanora, Joanna, Margaret, Mary, and Elizabeth.

I’ve got to say the book has a shaky start. Wilson-Lee sets up a questionable and unnecessary straw woman in her introduction: a “popular” vision of medieval princesses as powerless and passive that she describes as built on “an empire of fairy stories, Hollywood films, theme parks and cheaply produced ball gowns.” Personally, I’m not sure anyone believes in the powerless princesses she describes–not the little girls who wear those ball gowns with attitude* and certainly not anyone who would chose to read a book titled Daughters of Chivalry. Maybe that version of princesses existed once upon a time, but my own memory of fairy tales includes a fair number of princesses who used every ounce of power they held to control who they married–something only one of the real-life medieval princesses in Daughters of Chivalry managed to control.

That quibble aside, Daughters of Chivalry is an excellent book.

Like even the most elite medieval women, Wilson-Lee’s princesses left a spotty trail in the historical record, most often appearing in official chronicles in the context of their relationship with one of the men in their lives. She fleshes out the picture of their lives using a variety of sources—most notably the account records for the various royal households**—plus a certain amount of informed speculation.

Wilson-Lee uses her sources to good effect. She creates portraits of five clearly defined individuals. Joanna, for instance, frequently defied her father and took full advantage of the opportunities accorded to a young, wealthy widow in medieval society. Mary, who entered the convent of Amesbury at the age of six, had a taste for luxury and a gambling habit at odds with her vow of poverty. She also places the sisters within the larger context of royal women in the late medieval period, exploring questions of education, marriages (political and otherwise), widowhood, property, travel, and the role of royal women as political intercessors. Like the women she describes, Wilson-Lee never loses sight of the fact that what power these women enjoyed was derived from their relationship to the king, but she fully explores the nature of that power and how they used it.

*A year or two ago, I saw a little girl stomping through the aisles of my local grocery store wearing hiking books with a princess gown and carrying a sword. I’m pretty sure she didn’t share Wilson-Lee’s “popular” vision of princesses.

**The nature of her sources means there is a lot of description of real-life princess dresses. This is not a complaint. Just an observation.

May 27, 2024

From the Archives: Nancy Marie Brown and the Real Valkyrie

If you’ve been hanging out here in the Margins for a while, you know that I am fascinated by the continuing archaeological discoveries of ancient women warriors. Sometimes they are genuinely new discoveries. Sometimes they are a result of someone taking a closer look or asking new questions about existing. remains. This trend started in 2017, when Swedish bioarcheaologists released their findings that an iconic Viking war known as the Birka man was in fact the Birka woman. Their results raised a huge flap in the world of Viking studies.

In the intervening years, scholars have begun to ask more complicated, or at least different, questions about sex, gender and remains. These questions, and the Birka woman herself, are at the heart of Nancy Marie Brown’s The Real Valkyrie.

Brown takes the reader on a deeply researched and richly imagined exploration of the possible life of the Birka woman, whom she names Hervor. She interweaves a narrative of what Hervor’s life might have been like with the research on which she bases that narrative. She looks closely at the assumptions at the root of many of those long-held beliefs.* She asks new questions of sagas, chronicles, and archeological sources—and leads the reader through what those sources can tell us. She introduces us to a broader version of the Viking world, and to many powerful Viking women who have been previously dismissed as fiction. In the process she upends much of what we have traditionally believed about Viking women. The end result is a complex and important addition to women’s history.

It is also a fast-paced, delightful read, with lots of “wow!” moments along the way.

If you’re interested in Vikings, women warriors, women’s history, or how historians work with evidence, this one’s for you.

*Medieval Christianity, Victorian ideas about women and a historical novel written by a Swedish writer during World War II all helped shape our popular conceptions about Vikings.

May 23, 2024

From the Archives: The Crusades from Another Perspective

Recently* I’ve been reading Sharan Newman’s Defending The City of God: A Medieval Queen, The First Crusade And The Quest for Peace In Jerusalem. It was a perfect read for March, which was Women’s History Month.*

Recently* I’ve been reading Sharan Newman’s Defending The City of God: A Medieval Queen, The First Crusade And The Quest for Peace In Jerusalem. It was a perfect read for March, which was Women’s History Month.*

Newman tells the story of a historical figure who was completely new to me. Melisende (1105-1161) was the first hereditary ruler of the Latin State of Jerusalem, one of four small kingdoms founded by members of the First Crusade. Her story is a fascinating one. The daughter of a Frankish Crusader and an Armenian princess, Melisende ruled her kingdom for twenty years despite attempts by first her husband and then her son to shove her aside. Even after her son finally gained the upper hand, Melisende continued to play a critical role in the government of Jerusalem. Those few historians who mention Melisende at all tend to describe her as usurping her son’s throne.** Newman makes a compelling argument for Melisende as both a legitimate and a powerful ruler. (In all fairness, this is the kind of argument I am predisposed to believe.)

Fascinating as Melisende’s story is, Newman really caught my attention with this paragraph:

Most Crusade histories tell of the battle between Muslims and Christians, the conquest of Jerusalem and its eventual loss. The wives of these men are mentioned primarily as chess pieces. The children born to them tend to be regarded as identical to their fathers, with the same outlook and desires. Yet many of the women and most of the children were not Westerners. They had been born in the East. The Crusaders states of Jerusalem, Edessa, Tripoli, and Antioch were the only homes they knew.

Talk about a smack up the side of the historical head!

If you’re interested in medieval history in general, the Crusades in particular, or women rulers, Defending the City of God is worth your time.

*FYI This review originally ran in 2014.

**It was also nice to spend some time in a warm dry place, if only in my imagination. Here in Chicago, March came in like a lion and went out like a cold, wet, cranky lion.

*** To put this in historical context. Melisende’s English contemporary, the Empress Matilda (1102-1167) was the legitimate heir to Henry I. After Henry’s death, her cousin Stephen of Blois had himself crowned king and plunged England into a nine-year civil war to keep her off the throne. Apparently twelfth century Europeans had a problem with the idea of women rulers.