Pamela D. Toler's Blog, page 20

March 24, 2024

Talking About Women’s History: A Bunch of Questions and an Answer with Jennifer Lunden

Jennifer Lunden (she/her) is the author of American Breakdown: Our Ailing Nation, My Body’s Revolt, and the Nineteenth-Century Woman Who Brought Me Back to Life, which was praised by the Los Angeles Review of Books and Washington Post, and called a “genre-bending masterpiece” by Hippocampus. The recipient of the 2019 Maine Arts Fellowship for Literary Arts and the 2016 Bread Loaf–Rona Jaffe Foundation Scholarship in Nonfiction, Lunden writes at the intersection of health and the environment. Her essays have been published in Creative Nonfiction, Orion, River Teeth, DIAGRAM, Longreads, and other journals; selected for several anthologies; and praised as notable in Best American Essays. A former therapist, she was named Maine’s Social Worker of the Year in 2012. She and her husband, the artist Frank Turek, live in a little house in Portland, Maine, where they keep several chickens, two cats, and some gloriously untamed gardens.

Take it away, Jennifer!

What inspired you to write American Breakdown?

I’d been disabled by what’s now known as myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome, or ME/CFS, for five years when I stumbled upon Jean Strouse’s brilliant 1980 biography of Alice James in a used bookstore. I knew Alice was the sister of the nineteenth-century author Henry James and the psychologist William James, and that she spent much of her life bedridden by a mysterious illness. So I bought the book. It changed my life. Alice’s symptoms and mine were so similar I wondered if our illnesses might be one and the same, and I wondered if anyone else had made that connection.

In 2001 I asked a research librarian to help me search for papers connecting ME/CFS with Alice’s illness, neurasthenia, and she found a handful. Reading and researching was something I could largely do in bed, and I began doing so voraciously.

I wanted to write a book about ME/CFS and multiple chemical sensitivity because the biased perceptions faced by those of us who suffer from these and similarly misunderstood illnesses from doctors, researchers, the media, and the general public is harmful to our health. The further I delved into my research, however, I could see that America’s rapacious form of industrial capitalism is bad for all of us. So, like the ripples around a stone tossed in the water, my story started with Alice and me and expanded outward.

In American Breakdown, you combine memoir, biography and medical history to produce a complex exploration of industrialization and its impact not only on the environment but on healthcare in the United States. How did you navigate the narrative requirements of three very different types of storytelling?

What I love about the braided narrative is that it allows for a telling that includes head and heart. In other words, it is a way to connect mind and body. This was especially important to me because one of the key themes I tackle in the book is the problems posed by the limitations of our dualistic approach to medicine and to life in general. Biologically, and ecologically, we’re much more complex than that, and that’s a beautiful thing.

I knew that I wanted to include data and research that legitimized my experience and the lived experiences of others who, like me, live with the poorly understood, complex, multi-system illnesses that primarily strike women. I wanted skeptics to be able to read my book and know they could turn to the endnotes and see that what I was saying was backed by peer-reviewed research.

But I also knew if I didn’t include story that the book would be dry and hard to get through. So as I was interweaving the strands, I listened to my body, which told me when the facts were getting to be too much, and I would break there and put in a segment from my own story, or Alice’s.

And even when I was writing about dualism, I started by reading one or two biographies of Descartes, who is attributed as the thinker behind dualism, and I wove some of his story into the narrative about dualism.

We learn more effectively through story than through data; I felt that I could broaden people’s perspectives about these contested illnesses by opening their hearts through my illness story, and Alice’s.

Writing about a historical figure like Alice James requires living with her over a period of years. What was it like to have her as a constant companion?

Finding Alice felt like finding my kindred spirit, my illness comrade. Alice was witty and whip-smart, and, like me, often bedridden due to a poorly understood illness.

Here’s an Alice quote that still makes me laugh out loud, written to a friend when Alice was 31:

Ill-health though not an exceptional or tragic fate inevitably brings a certain monotony into the lives of its victims which makes them rather sceptical [sic] of the much talked of and apparently much believed-in joy of mere existence.

And when she was diagnosed, at 42, with breast cancer, her response wasn’t what most people would expect, but it deeply resonated with me. As she enthused in her diary, finally, and to her great relief, she was lifted “out of the formless void” and set down “within the very heart of the sustaining concrete.”

While most of us chronically disabled by similar illnesses aren’t ready to embrace death the way Alice was, I suspect that just about anyone who has contended with ME/CFS, multiple chemical sensitivity, long Covid, or any one of a number of other poorly understood illnesses can identify with Alice’s relief at finally receiving a concrete diagnosis, one recognized as “real” and valid in their world.

Alice’s doctor, “the blessed being,” had also “endowed” her with “not only cardiac complications,” but also a “most distressing case of nervous hyperaesthesia” (hypersensitivity of one or more of the senses of sight, sound, touch, and/or smell). These, she wrote triumphantly,

added to a spinal neurosis that has taken me off my legs for seven years; with attacks of rheumatic gout in my stomach for the last twenty, ought to satisfy the most inflated pathologic vanity. It is decidedly indecent to catalogue oneself in this way, but I put it down in a scientific spirit, to show that though I have no productive worth, I have a certain value as an indestructible quantity.

Here, while reveling in her concrete diagnoses, Alice simultaneously pushes against capitalistic definitions of human worth and expands the definition of our value. It’s an early expression of disability pride.So I would say that Alice resided in my heart over the many years it took to write this book. She helped to sustain me.

How did your training as a social worker and therapist inform your work on American Breakdown?

I didn’t realize until 2017, when I began teaching a foundational graduate social work course called Human Behavior in the Social Environment, how social-worky American Breakdown is. Social workers are trained to look for the contexts contributing to the personal difficulties people are facing. My curiosity about the sociocultural contexts that influenced my biology, and Alice’s, took me on a journey beyond anything I envisioned when I started writing—research that included American history, of course, and biology, but also nineteenth-century and contemporary toxicology, medical history, economics, environmental history, sociology, chaos theory, and more, and the process of synthesizing what I learned into a narrative interwoven with both my story and Alice’s was deeply illuminating.

What work of women’s history have you read lately that you loved? (Or for that matter, what work of women’s history have you loved in any format? )

Well, I’ve only just started reading it, but I highly recommend National Book Award winner Tiya Miles’s new book Wild Girls: How the Outdoors Shaped the Women Who Challenged a Nation.

A question from Jennifer: I see that, in addition to Women Warriors and the forthcoming The Dragon from Chicago, you are also the author of The Everything Guide to Understanding Socialism. How do your understanding of socialism and your interest in women’s history inform each other?

I must admit that I am interested in many, many things and the relationships between them in my head are more like a tangled knot of yarn than a web.

In the case of socialism and women’s history, the most obvious link is that I have long been interested in women’s involvement in social reform movements in the mid-nineteenth to the earlier twentieth century, whether we’re talking about Jane Addams and her colleagues at Hull House or Mother Jones and the labor movement. That link shows up clearly in my book on Civil War nurses, for example.

Other threads leading into that knot of yarn are fundamental interests in stories that stand outside the primary historical narrative (labor history and women, for example), how social change happens, and the people I call shin-kickers.

***

Want to know more about Jennifer Lunden and her work?

Check out her website: https://jenniferlunden.com/

***

Come back tomorrow for two, or five, questions and an answer with Natalie Dykstra, author of Chasing Beauty: The Life of Isabella Stewart Gardner

March 21, 2024

Lost Women of Science

I want to share another women’s history treasure, which appeared in one of my social media feeds immediately after the Oscars: a podcast mini-series titled Lost Women of the Manhattan Project. The mini-series focuses on eight women scientists, but does not allow the listener to forget that hundreds of women scientists were involved in the Manhattan Project. Each of the short episodes opens and closes with a recital of the names of women who worked as scientists on the project.

The mini-series provides an interesting counterpoint to the film Oppenheimer, in which the women are represented by only one of their number.* In all fairness, biographical films are inherently limited in what they can portray. On the other hand, that kind of reasoning is why women have been, and obviously still are, left out of the historical narrative. One reason the film Hidden Figures is so powerful is that it answers a question that was not asked in films like The Right Stuff and Apollo 13. Perhaps we need a film of The Girls of Atomic City as a pendant to Oppenheimer. In the meantime, we have this series of brief podcast episodes to give us a glimpse of the possibilities. Here is the link: https://www.lostwomenofscience.org/season-6

The Lost Women of the Manhattan Project is the creation of Lost Women of Science, which produces podcast episodes devoted to individual women scientists and has recently begun a news series of interviews with people working on the history of women in STEM.

Good stuff all around.

*Which is better than none of them appearing at all.

****

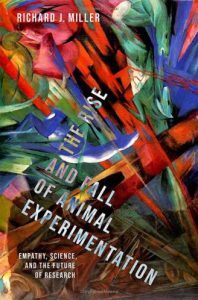

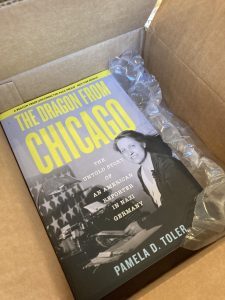

Just a reminder, The Dragon from Chicago is available for preorder wherever you get your books. If you want a signed copy, you can order it here: https://www.semcoop.com/ingram-0?isbn... There is a space at the bottom of the order page to add special instructions. Request a signed copy there, and specify how you want the book to be signed.

****

Come back on Monday for three questions and an answer with Jennifer Lunden, author of American Breakdown: Our Ailing Nation, My Body’s Revolt, and the Nineteenth-Century Woman Who Brought Me Back to Life.

March 20, 2024

Talking About Women’s History: Three Questions and an Answer with Laurie Wallmark

If you’ve hung out here at the Margins, you’ve probably read one of my occasional paeans to the biographies of kick-ass women that were in the library in my elementary school. (In fact, now that I think about it, the subject came up in a Q & A with Kip Wilson earlier this month.) They inspired my life-long interest in women’s history.

Today’s guest, Laurie Wallmark, writes similar biographies, aimed at slightly younger readers, with the twist that she focuses on women in STEM which means she may well be inspiring young engineers, scientists, coders, and astronauts as well as baby historians. Before she began writing, Laurie worked as a software engineer, a computer science professor and the owner of an internet-based bookstore. (Before Amazon! )

She is the author of seven picture book biographies of women in STEM: THE QUEEN OF CHESS (Little Bee, 2023), HER EYES ON THE STARS (Creston Books, 2023), CODE BREAKER, SPY HUNTER (Abrams, 2021); NUMBERS IN MOTION (Creston Books); HEDY LAMARR’S DOUBLE LIFE (Sterling Children’s Books, 2019); GRACE HOPPER: QUEEN OF COMPUTER CODE (Sterling Children’s Books, 2017); and ADA BYRON LOVELACE AND THE THINKING MACHINE (Creston Books, 2015).

Take it away, Laurie!

The biographies you write all deal with women in STEM. How do you make complex ideas understandable to young readers?

When I was in grad school (MFA in writing), I wrote my thesis on how to explain STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering, and Math) in picture books. The title of my thesis? “It’s Complicated (Not Really).” There are so many techniques an author can use to provide kids the tools they need to understand complex STEM ideas and concepts. It’s up to the author to choose the ones that will work for each situation. From word choice to in-text definitions, analogies to relatable context, even the most difficult information can be made understandable. For example, in my book Numbers in Motion, I say that partial differential equations define the rules about how something changes. That’s all that the reader needs to know. They don’t need to understand the complicated mathematics behind these equations.

How do you choose subjects for your biographies?

There are two main questions I ask myself when choosing a subject. First, do I think the person’s life and accomplishments will be interesting to and second, will it have meaning for a child. If not, why write it?

After that, I consider additional questions. Is there enough source material available? Are there already recent books written about the person. Finally, am I drawn to learning more about the person? After all, in writing a biography, you have to spend a lot of time immersing yourself in the person’s world.

Do you think Women’s History Month is important and why?

In a perfect world, we wouldn’t need a month dedicated to the history of a specific group (like women, Black people, LGBT people, etc. ) The story of their lives would be part of the general history that kids learn about. But, let’s just say we don’t live in a perfect world. The accomplishments of underrepresented groups are often overlooked or minimized. Having months like Women’s History Month, gives educators an opportunity to shine a light on the achievements of members of these groups.

A question from Laurie: Do you think that by having a month dedicated to women’s history, it gives people an excuse to ignore women’s contributions during the rest of the year?

Maybe it’s wishful thinking on my part, but I think that is less and less true with time.

Since Women’s History Month was created in 1987, at least two generations have grown up learning about women’s history each year in school. Numbers of them have gone on to highlight women’s history in exciting ways outside of March—some of whom have appeared here on the Margins over the years. And it is clear they have an audience.

***

Want to know more about Laurie Wallmark and her work?

Check out her website: https://www.lauriewallmark.com/

Like her on Facebook: Laurie Wallmark – author

Follow her on the platform previously known as Twitter: @lauriewallmark

Follow her on Instagram: lauriewallmark https://www.instagram.com/lauriewallm...

Follow her on Bluesky: @lauriewallmark.bsky.social

***

Tomorrow it will be business as usual here on the Margins with a blog post from me. Then we’ll be back on Monday with Jennifer Lunden, author of Americana Breakdown.

March 19, 2024

Talking About Women’s History: Three Questions and an Answer with Marcia Biederman

Once a mystery novelist, Marcia Biederman now writes meticulously researched nonfiction that reads like a detective story. As a longtime freelancer for the New York Times, she wrote more than 150 pieces for the Times on everything from ice dancing to automobile wheel repair. She was a staff reporter for Crain’s New York Business, and her work has appeared in New York magazine, the New York Observer, the Christian Science Monitor, and Newsday. Before discovering her passion for history, biography, and true crime, she published three mystery novels and contributed a short story to Best of Sisters in Crime, edited by Marilyn Wallace.

The Disquieting Death of Emma Gill: Abortion, Death, and Concealment in Victorian New England, is Marcia Biederman’s fourth nonfiction work about women whose stories should be better known. Her previous books are A Mighty Force, about Pennsylvania coal town physician Elizabeth Hayes; Scan Artist, about speed-reading entrepreneur Evelyn Wood; and Popovers and Candlelight, about New York restaurateur Patricia Murphy.

Take it away, Marcia!

What path led you to Emma Gill’s story? Why do you think it is important to tell her story today?

More than four years ago, I was researching a different topic when I stumbled across an 1898 edition of the Los Angeles Herald headlined, “The Mysterious Tragedy of Bridgeport.” There are many American cities named Bridgeport, but a quick scan confirmed this was about my hometown – Bridgeport, Connecticut, where I was born and raised. Robustly illustrated with drawings of suspects, victim, and crime scene, the piece told a story I’d never heard.

A young woman’s mutilated remains had been found in a pond. A medical examination immediately indicated that the woman had died of an infection following an abortion – a serious crime at that time in Connecticut, and, indeed in every state – with the body cut up afterward to conceal what had happened.

Immediately, I was hooked. In that piece, abortion wasn’t mentioned directly, but there were multiple mentions of the “midwife” under suspicion. Bridgeport seldom makes national news now, and it never did. This had to be big.

Digging further, I found this was more than just a police-gazette-style story. The yellow press – the Hearst chain, etc. – was all over it, but reputable papers like the Hartford Courant and the New Haven Register provided more sober coverage. The Bridgeport Herald, now extinct, astounded me by calling for sex education for girls, criticizing prudishness, and writing that Nancy Guilford – the suspected abortion provider, who eluded the police for weeks – “simply was unfortunate in getting caught in an unlawful act which is being repeated weekly in every city in this state.”

Statements like that floored me. They also spurred me on to write the book. As I began my research in late 2019, Roe v Wade was still the law of the land, but I knew it was under attack. In many parts of the country, opponents of reproductive rights had closed abortion clinics or made it impossible for them to open. Years ago, I’d read a book by the historian James C. Mohr, Abortion in America, which talked about how widespread abortion became in the nineteenth century, moving from the margins into the mainstream (yet here I am, being interviewed by History in the Margins!)

State legislatures responded by tightening laws against abortion, but the cases were hard to prosecute, and many people tolerated, or even welcomed, criminal abortion providers in their midst. As I recently wrote in a newspaper op-ed, only Robin Hood had more accomplices. If abortions led to lethal infections — always a risk in the era before modern antibiotics — the patient’s family would help conceal the cause of death. At least that was true in the Connecticut and Massachusetts cities where Nancy Guilford’s practices flourished until the disposal of a body went terribly wrong in two separate cases and Guilford served long prison sentences, only to get right back to it after release.

Emma Gill was a name that didn’t pop up until I was far into my research. The case remained unsolved for months, and Nancy Guilford remained at large, because no one could identify the dead woman. Fingerprinting identification was not yet available, so the police put the severed head on display in the city morgue. Hundreds of Bridgeport residents filed past it, but no one recognized the face. Emma Gill, as it turned out, was from Southington, near Hartford. In the meantime, mailbags full of tips arrived at the Bridgeport police department. Everyone, it seemed, had a sister, wife, or neighbor who’d been away from home for a few days and who – according to her siblings, spouse, or co-worker – might well have gone for an abortion, despite the fact that the procedure was strictly illegal.

As I discovered more about Nancy Guilford and her husband – old-stock white Protestants – it became clear to me that abortion was as American as apple pie. While I was halfway through the writing, I became more determined than ever to tell this story. Writing for the Supreme Court majority in the Dobbs decision that overturned Roe, Justice Samuel Alito stated that the right to abortion is not “deeply rooted” in American history or traditions. My book proves him wrong.

Are there special challenges in writing about a historical event with echoes in current politics?

Yes. Abortion is one of the most controversial topics of our time, so there are special challenges even when writing about events that happened 125 years ago — not so much in writing the book as in selling it to publishers and marketing it. I’m fortunate to have Chicago Review Press as my publisher. Before they offered me a contract, an acquisitions editor at a much larger publishing house became interested and set up a Zoom call to discuss it. Initially, only the editor, my agent, and I were going to be on the call, but one of the editor’s superiors invited herself at the last minute and dominated the conversation. The editor started by asking if I thought of Nancy Guilford, the abortion provider at the center of the book, as a “delicious villain.” Now, as a criminal who enriched herself by fulfilling a need, Nancy was a seriously flawed person who sometimes set her own interests above those of her patients. She was also married to a genuine villain and, at least for a while, did bad things to cover for him. The fact that they were both engaged in crime made it difficult for her to leave him, though she tried.

As I began to explain these nuances, I could tell that the editor’s superior was losing interest. They never made an offer. When my book finally found a home, I was never asked to reduce complexities to simplicities. My editor trusted me, and no higher-up was trying to trim history to certain specifications.

As for marketing the book, there are benefits as well as drawbacks, depending how blue the state. Before publication, I was able to place op-eds related to the book in two Connecticut news outlets, the Hartford Courant and the CT Mirror, and in the New York Daily News. However, in Pennsylvania, a reporter who regularly contributes to two small newspapers was able to place a feture about the book in only one of those outlets. The other paper told her they were afraid of pushback from the antiabortion movement, which is active there.

On the plus side, a wonderful Manhattan bookstore, P&T Knitwear, arranged my book launch as a benefit for The Brigid Alliance, an organization that brings people from states with abortion bans to New York for care. We already know that the past can inform the present. It can also raise some money for it!

When did you first become interested in women’s history? What sparked that interest?

My local library, like many libraries known to baby boomers across the country, had a special case for several dozen books officially titled the Bobbs-Merrill Childhood of Famous Americans series. We called them “the orange biographies” for the color of the bindings. I devoured the ones about women as young girls: Amelia Earhart, Jane Addams, Dolly Madison. Supposedly they were nonfiction, but the dialogue and many events were made up. Today we’d call them historical fiction. Still, there was enough true stuff there to get me interested.

In addition, I formed a long-time obsession with Louisa May Alcott after discovering an abridged version of Little Women in the comic book racks at my neighborhood newsstand. I identified with Jo, obviously a stand-in for the author, and devoured what I could about her creator. I especially loved John Matteson’s 2008 biography, Eden’s Outcasts, about Louisa’s relationship with her father, Bronson Alcott.

Hence, it was great fun to discover an indirect connection between Louisa May Alcott and the people and events in my latest book, The Disquieting Death of Emma Gill. The abortion provider at the center of the book, Nancy Guilford, learned “the criminal operation,” as it was then called, by assisting her husband, Henry Guilford. But how did Henry learn it? Henry claimed to have a medical degree, although I could find no evidence of that. Nonetheless, newspaper reports show that he worked as an in-house doctor at one of the Health-Lift exercise salons popularized by one of Louisa May Alcott’s cousins, a Harvard-trained physician and bodybuilding enthusiast named George Barker Windship.

Related to Louisa through the Mays, her mother’s side of the family, weightlifting George and his scribbling cousin had much in common. According to her biographer Matteson, Alcott was a dedicated runner. Jo March, of course, was an athletic type, and in Eight Cousins, Alcott presented a male character, a kindly uncle, who encouraged girls to dress in less restrictive clothing and exercise more.

When Louisa’s strongman cousin, George, died suddenly of a heart attack at age 42, the Health-Lift craze screeched to a halt. People lost faith in the exercise machines, some modified for use by women, a significant portion of the clientele. My research suggests other reasons for the sudden plunge in popularity. At least two people involved in Massachusetts abortion trials had worked at Health-Lift gyms. Henry Guilford, a “doctor” for one of the gyms, may have learned his trade there. When the gyms closed, he and his wife, Nancy, opened their own abortion practice in Worcester, Massachusetts. All this gave me a whole new perspective on the Alcott family tree.

A question from Marcia: Can you think of any other books (or works about history in any format – biopic, documentary) in which a tale from the past strongly resonates today, whether about reproductive rights, banned books, vaccinations, trans rights, threats to democracy, etc.?

I spent much of the last four years in a deep research dive on Germany in the 1920s and 1930s, the isolationist movement in the United States during the same period, and the challenges journalists faced in reporting both stories. It was uncomfortable reading. All too often, what I was reading in the morning’s paper—or at least the on-line versions thereof— echoed the stories from the past that I was researching.

For example, watching our current debates over support to Ukraine, I keep thinking about Lynn Olson’s Those Angry Days: Roosevelt, Lindbergh, and America’s Fight Over World War II, 1939-1941. In it, Olson explores how the issues of interventionism and isolationism split American society in the years before the United States entered World War II. She centers the story on the larger than life figures who embodied the two positions: President Franklin Roosevelt and Charles Lindbergh. (Neither man comes out looking good.) But the story is more than a Clash of Titans. Olson takes us through the conflict in step-by-step detail, looking at grassroots activism as well as the actions of those in power. She introduces the reader to individual members of Congress who took positions on both sides of the conflict, bringing them to life in unexpected ways. She looks at high-ranking officers in the American military who were anti-intervention and who actively worked to undermine Roosevelt’s pro-British policies. She outlines the workings of a covert British operation which created false news, dug up dirt on isolationist Congressmen, and helped form the OSS, precursor to the CIA. She describes the formation and actions of isolationist groups like the America First Committee and the American Mothers Neutrality League and their interventionist counterparts, the White Committee (officially the Committee to Defend America by Aiding the Allies) and the Century Group.

It was a dirty fight on all sides, until the attack on Pearl Harbor made the debates largely irrelevant.

***

Want to know more about Marcia Biederman and her work?

Check out her website: https://marciabiederman.com/

Follow her on Instagram: @squiremarcia

***

Come back tomorrow for three questions and an answer from children’s author Laurie Wallmark, who writes about women in STEM.

March 18, 2024

Talking About Women’s History: Three Questions and an Answer with Richard Miller

Richard Joel Miller was born in Portman Square in London, England. He developed an interest in chemistry when his father gave him a chemistry set for his fifth birthday. Following an unfortunate series of events involving explosions in the family garage, his interests (much to his parents’ relief) shifted to the finer points of biochemistry, and a desire to use science to understand the workings of the brain. Richard obtained his PhD from Cambridge University and then joined the faculty of the University of Chicago in 1975. After 25 years he transferred to the Department of Pharmacology at Northwestern University, where he is now Professor Emeritus.

Richard has published over five hundred scientific papers and four books in the areas of biochemistry, physiology, pharmacology, and neuroscience. In his latest book, The Rise and Fall of Animal Experimentation (OUP), Richard looks back over decades of research, examining the use of animals in science and exploring: Why do we do it? Is it successful, i.e. does it further translational medicine? Is it ethical? He also discusses the ever-increasing use and potential of human stem cells and related technologies in creating experimental models, making animal-based research ultimately obsolete.

Take it away, Richard!

Did you expect women to play a role in your study of animal experimentation when you began your work?

What was the most surprising thing you’ve found about women’s involvement in animal rights activists while doing historical research for your work?

When I first began this project I didn’t really have any expectations about the role of women in the history of animal experimentation and the animal rights movement. I must admit that it wasn’t something I had really thought about. But, as it turned out, there was a lot to learn. Of course, to begin with, as you go through the history of animal experimentation which began in antiquity, you only read about men. It’s men who performed the experiments. Moreover, nobody had much to say about animal rights. Once you get to the 16th century, there was Montaigne who wrote eloquently about the reasons why we should respect the intelligence and feelings of animals. Then in the 17th century there was Margaret Cavendish, the first women to write about these topics, followed by others in the 18th century. Suddenly, in the 19th century, there were a huge number of women involved in the animal rights movement; actually, I think it was mostly women! Why was this?

The animal rights movement started in England where the first laws to protect animals were presented to Parliament at the start of the 19th century, although none of them got anywhere for several decades. There weren’t any women Members of Parliament (MPs) in those days. On the other hand, women were starting to speak out about their roles in society in general and so became associated with a whole group of causes that concerned “rights”, including the anti-slavery movement, animal rights and suffragettism. Most of the women you read about were simultaneously active in all these movements. They had to find ways of supporting their beliefs outside of Parliament. Hence, it was women who founded many of the animal welfare movements such as the societies that opposed vivisection. In fact, it was a woman named Frances Power Cobbe (1822–1904), who initiated the antivivisection movement in Great Britain. A prolific author, she published numerous essays on animal rights and feminist philosophy. In 1875, she founded the Victoria Street Society which became the Society for Protection of Animals against Vivisection. The efforts to promote animal rights in England soon spread to the USA and the Continent. Queen Victoria, who was a great animal lover, joined the antivivisection movement, which gave it a lot of credibility and made it fashionable.

What really surprised me was just how radical these women were both in the context of animal welfare and suffragettism. These days you hear about members of groups like PETA acting as agent provocateurs, infiltrating laboratories, and reporting on what they see. The female antivivisectionists in the late 19th and early 20th centuries did precisely the same things. There was a famous incident when two women antivivisectionists infiltrated a medical school demonstration where a dog was being dissected and then wrote a book about it called The Shambles of Science. The book provoked all kinds of grass roots activism. A statue was put up in Battersea Park celebrating the dog, leading to riots involving thousands of people who were pro or anti-vivisection. This became known as “The Brown Dog Affair”. These women really put themselves in harm’s way and were incredibly brave and energetic in pursuing their goals. It was fantastic. I never knew anything about all of this, and I was extremely impressed.

You write about a number of women ranging from the seventeenth century polymath Margaret Cavendish, Duchess of Newcastle through twentieth century animal rights activists. Do you have a favorite, or two?

Well, yes, you do have to like “Mad Madge” (Margaret Cavendish) in the 17th century, for one. She was an amazing person. She wrote about cruelty to animals, and did a lot of other things as well, including writing the first science fiction novel-The Blazing World, together with a great deal of poetry and essays on natural philosophy (science). Notably she published her works under her own name, something that was unheard of for women at that time. She was fearless. She made waves. Everybody turned out to see what she was wearing, and they were frequently shocked. Once she was even seen wearing a man’s coat! People just couldn’t believe it. She was the Vivienne Westwood of her day; a punk goddess, avant la lettre.

Margaret Cavendish was also the first woman to attend a meeting of the Royal Society, the world’s original and most prestigious scientific society where she engaged with some of the greatest scientists of the day like Sir Robert Boyle. In the 18th century, following Cavendish, other women began to publish under their own names and would comment negatively on the use of animals in laboratories. Susanna Centlivre, for example, in her play The Basset Table, introduced Valeria, a virtuosa (female scientist) who performs cruel experiments on dogs.

Less famous than Margaret Cavendish, but of great importance, was Lizzy Lind Of Hageby. She was born in Sweden in 1878 to an aristocratic and extremely wealthy family but settled in England following her education at Cheltenham ladies’ college. Lizzy lived the rest of her life in England, mostly in London, where she shared her home with another women, Leisa Schartau, also originally from Sweden. Leisa shared Lizzy’s views on many topics. For example, they wrote about the training of medical students:

“What is the influence on students who attend demonstrations where live animals, cats and dogs and rabbits, are cut open before the class to demonstrate some scientific theory? There are very few who would not acknowledge that it is far, far better to make boys and girls humane and merciful men and women, with hearts and well as heads, than to make them learned and intellectual, but heartless and cruel.”

It should be remembered that ideas connected with spiritualism and theosophy were extraordinarily influential in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. These included the goal of uniting all men and women equally at the spiritual level in their search for divine wisdom. Both Lizzy, Leisa and the majority of their female associates were devoted followers of Henrietta Blavatsky and her theosophical ideas. Madame Blavatsky’s successor as head of the Theosophical society, Annie Bessant, was also an active participant in the drive for animal rights. Indeed, many of the women who were active at this time promoted “rights” of many types as well as other ideas. These included human rights, animal rights, suffragettism, theosophy and spiritualism. They also invariably promoted other ideas which would seem outmoded to us today, such as strong opposition to vaccination (yes, it’s nothing new) and germ theory. They also shared a general belief in animal telepathy.

Lizzy was an absolutely incredible person. She had a brilliant intellect, and was indefatigable. She founded the Animal Defense and Antivivisection Society and helped to found similar societies all over the world, organizing many international meetings on the topic of animal rights. She was extremely active at the personal level and often put herself in danger physically in public in support of the causes she believed in; she was involved in the riots that accompanied the Brown Dog Affair, as discussed above. She would also give frequent public lectures and debated representatives of universities and hospitals who supported vivisection. She always won these debates as she was an extremely effective public speaker. And her achievements in the sphere of animal rights weren’t the only things she did. She had great sympathy for suffering of all sorts, both humans and animals, and, for example, went to Europe during the First World War where she opened institutions to take care of wounded soldiers and others to rehabilitate horses. If that wasn’t enough, she wrote numerous books, including the first biography of her Swedish compatriot the playwright August Strindberg. When she died in 1963, she left her fortune to the Animal Defense Trust, which she founded, and which continues to offer grants for animal-protection issues, so that her influence lives on today. Just thinking about all her accomplishments leaves me breathless.

What unsung woman activist from the past would you most like to read a biography of, and why?

There are certainly a large number of women whose roles in the history of the animal rights movement have not been well researched, but there is one in particular I would like to mention. Before I do, however, let me explain the situation with respect to the use of animals for laboratory research in 19th century science. Using animals for vivisection is something that goes back to the work of people like William Harvey in the 17th century when he discovered the circulation of the blood; his research was based primarily on animal vivisection. In the 17th century science was only practiced by relatively few wealthy gentlemen like Harvey. But, by the 19th century science had become a profession and so the number of scientists had increased enormously. The tradition of vivisection was mostly advanced in France. The most important of all the French physiologists in the 19th century was Claude Bernard. He is considered one of the greatest physiologists of all time and he introduced many key concepts into biology and medicine. One key idea was that of homeostatic regulation, that tissues always respond to changes in other tissues in an attempt to maintain a state of equilibrium. Bernard’s most productive experimental paradigm was vivisection, particularly of dogs. Nevertheless, whatever his scientific achievements, there is no doubt as to the profound cruelty of the procedures he carried out. Indeed, the burgeoning anti-vivisection movement of the time, particularly in England, took notice of what Bernard was doing and his work became controversial.

One thing to note is that Bernard didn’t come from a rich family and his scientific research cost a good deal of money. So, he made sure that he married a wealthy woman. In those days, once married, all of a wife’s money became the property of her husband. The woman Bernard married in 1843 was Marie-Françoise (“Fanny”) Bernard (née Martin) whose dowry was used to finance his research. It was an arranged marriage but, unfortunately, vivisection became a point of contention between the couple. Fanny and the couple’s two daughters, Marie-Claude (1849-1922) and Jeanne Henriette (1847-1923) were absolutely horrified by Bernard’s nightly expeditions around Paris trapping stray animals for his vivisection studies. It is said that they once discovered a neighbor’s missing dog on his operating table. The couple ended up divorcing, something that was very difficult to do in a Catholic country like France. Fanny Martin became committed to the animal rights cause, joining the Société Protectrice des Animaux (Society for the Protection of Animals), which was founded in 1846. Fanny Martin and her daughters also opened and ran an animal shelter where they would rescue dogs and cats. Fanny and her youngest daughter helped to create a dog cemetery in Asnières and were active in the emerging French antivivisection movement in many ways. Fanny Martin became one of her ex-husband’s fiercest opponents.

Unfortunately, history has ignored Fanny Martin. She is really only discussed in the context of the fact that she was Claude Bernard’s wife and her antivivisection sympathies, from the point of view of scientists, are considered to be aberrations. However, Fanny Martin exhibited incredible bravery in opposing her husband at a time when such thing was simply not done. Moreover, it wasn’t just the fact that she stood up personally against Claude Bernard and the whole of the scientific edifice that supported animal experimentation, but the fact that she was extremely active in promoting the movement in France. Sadly, nobody has written a proper biography of Fanny Martin. It’s a great shame because she was really a hero of the animal rights movement.

A question from Richard: As we have seen, women played an essential role in the birth of the animal rights movement , particularly promoting animal issues outside the government (e.g. Parliament).Do you think that women have a unique role to play in the animal rights movement these days, considering the position of women in 21st century society?

[Pamela takes a deep breath and blows it out slowly] I know so little about this subject that I am diffident about offering an opinion at all. But here goes, based on the largely female staffs of the veterinary offices and animal shelters that I know, I suspect that women also make up a disproportionately large percentagel of the animal rights movement today. But honestly, I’m just riffing here.

***

Want to know more about Richard Miller and his work?

Check out his website: https://richardjmillerscientist.com/

Check out his LinkedIn profile: Richard J Miller

Follow him on Mastodon: @richardjmiller@mastondon.social

***

Come back tomorrow for three questions and an answer with Marcia Biederman, author of The Disquieting Death of Emma Gill. Abortion, Death, and Concealment in Victorian New England

March 17, 2024

Talking About Women’s History: Three Questions and an Answer with Sarah Percy

Sarah Percy is associate professor at the University of Queensland. The author of Mercenaries and Forgotten Warriors: The Long History of Women in Combat, she completed her MPhil and DPhil as a Commonwealth Scholar at Balliol College, Oxford. She lives in Brisbane, Australia.

Take it away, Sarah!

What inspired you to write Forgotten Warriors?

A historical puzzle got me thinking about the role women had played in combat in history. The first one is that the US had female astronauts thirty years before they had women in combat. Women were allowed to be armed police officers (and therefore shoot to kill) and were allowed into a variety of dangerous or previously all male jobs in the 1970s. But for some reason, combat remained about the only profession you can think of from which women were actually banned in the 21st century! I wanted to know why this was the case – especially in a context where a powerful women’s rights movement, including many lawsuits to break down barriers for women, had opened doors everywhere else. What was special about combat? To find out the answer to this puzzle, I had to understand what women had done on the battlefields of the past, which only made the puzzle more interesting – because there is plenty of evidence that women engaged in combat with great success. So the book became about finding out the answer to my puzzle, and telling the story of women in combat.

In Forgotten Warriors, you literally explore “the long history of women in combat. ” How did you decide which women to include?

One of the great joys of researching this book was finding out about all the amazing women combat fighters of the past. There are so many it wasn’t easy to choose, especially because Forgotten Warriors is not a compendium of women fighters (other people, including you, have done this so well!). But in a way, this made it easier. My goal with the book is to demonstrate that women fighters have been an integral part of broader military history, and consider how understanding their stories illuminates this conventional history in different ways. So I chose women whose stories helped me demonstrate the key arguments of the book: that women have always fought, but often been overlooked or even had their service deliberately forgotten, and that women’s military contributions have often been belittled because for whatever reason they are not considered to be fighting in ‘proper’ wars or on ‘real’ battlefields. One of the things I found most interesting was that many of the women in the book were actually pretty ordinary. They weren’t, in their pre-war lives, notably physically imposing. But when given the opportunity to fight, they excelled. I loved the stories of the ordinary British women who were recruited for the Special Operation Executive, and sent to fight behind enemy lines in occupied France. These women were chosen because they spoke French fluently and could go undetected while on operations. But they proved to be not only fierce fighters but also commanders of men. Pearl Witherington, one of these recruits, turned out to be the best shot her trainers had seen go through the course, and ended up leading a force of several thousand French resistance fighters after D-Day. But because she was a woman, she wasn’t considered to be a combatant, and she was only eligible for civilian honours at the end of the war. She returned her civilian honour and remarked that there was nothing civil about what she’d done during the war!

What was the most surprising thing you’ve found doing historical research for your work?

So many things! I hope my family were entertained when I would sit at the dinner table and tell them, “you’ll never believe what I found out today!!”. But probably the thing that ended up having the biggest impact on the book and surprised me the most was how important World War I is to understanding the history of women in combat roles. I was surprised because World War I is a really masculine war, and in fact it’s the most all-male war that I write about. While women were a relatively commonplace feature on 18th and 19th century battlefields (not always fighting, but often right at the front and in the thick of the action providing essential support services) by the early 20th century they’d been pushed out of European armies. So I thought that World War I would be a pretty dull period in a history of really rich examples of female fighting. But I found actually that it’s such a crucial turning point in the story. The advent of total war presented governments with a problem: they needed to have total social mobilization to win the war, but they’d done a very good job convincing their populations that women couldn’t be anywhere near the frontline (in fact the term “home front” is invented in World War I). So this meant that governments and militaries had to devise rules to keep women out of combat – and these rules persist throughout the 20th century. So World War I is a crucial turning point in the story – and, even more interesting, is what the women were actually doing! It’s true that women didn’t fight much in the war (although there are some great exceptions, including women who dressed as men and snuck into the military in Russia, and a Russian all-female military battalion, and quite a few other extraordinary women!). Women were however very significantly involved, because in almost every European state, women had organized themselves as auxiliaries long before governments realized they’d need women – and these auxiliaries became the nucleus of official women’s military service.

A question from Sarah: if you could travel back in time to visit one of the places you’ve written about (or meet one of the people) – who, when, why?? What would you talk about?

At the moment, I would chose Weimar Berlin.

The third-largest city in the world, with a population of four million, Kaiser Wilhelm’s stodgy, rather provincial capital became an international crossroads in the years after the war. Lillian Mowrer, wife of the Berlin bureau chief for the Chicago Daily News and a journalist in her own right, wrote in her memoir that Weimar Berlin reminded her “of a huge railway station; it was the stopping-off place between eastern and western Europe; everyone traveling from Paris to Moscow, sooner or later, came there.”

Weimar Berlin was politically tense, bawdy, and creative: the darker counterpart of interwar Paris. With the well-earned reputation of being the most licentious city in Europe, Berlin drew an international community of artists, political dissidents, journalists, intellectuals, and members of the Lost Generation engaged in what a later generation would term “finding themselves.” It was a period of enormous, almost hyperactive, creativity. Artists of all types—in film, music, photography, the visual arts, and the many forms of theater that flourished in the city—drew energy from the prevailing sense that the social norms had been broken twice, first by the war and later by the revolution. As a result, anything seemed possible–until it all fell apart.

I’d like to think I would talk to everyone, gone everywhere, seen everything. In reality, I would probably nurse a drink in a corner.

***

Come back tomorrow for three questions and an answer with scientist Richard Miller, author of The Rise and Fall of Animal Experimentation: Empathy, Science and the Future of Research, a story in which women play a surprisingly large role.

March 14, 2024

Wise Women

One of the things I enjoy most about Women’s History Month is the fact that people share interesting programs about women’s history that I would never have found on my own. Programs that I can then share with you.

One of the things I enjoy most about Women’s History Month is the fact that people share interesting programs about women’s history that I would never have found on my own. Programs that I can then share with you.

Today’s unexpected treasure is Wise Women, a sixteen-episode podcast series about women in philosophy, put on by Philosophy Talk, a radio program and series of podcasts produced by Stanford. The first season focuses on women from the fifth through the 19th centuries. I’ve heard of five of the eight women. Three are totally new to me.

The second season will focus on contemporary philosophers—I’m embarrassed to admit that not a single name comes to mind. Thought now that I think of it, I can’t name any contemporary male philosophers either.

Half the episodes of the first series have dropped. I’m part way through the first episode and I’m hooked. Both the narration and the graphics are excellent.

Here’s the link: https://www.philosophytalk.org/wisewomen

****

On another topic, I received galleys of The Dragon From Chicago a couple of days ago. They are gorgeous, and I am beside myself with delight, and maybe a little bit of terror, that this book is one step closer to going out into the world.

For those of you who missed it: the book releases August 6 but is available for pre-order now.

March 13, 2024

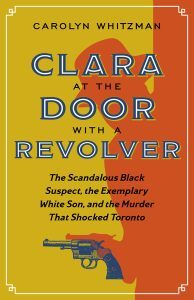

Talking About Women’s History: Three Questions and an Answer with Carolyn Whitzman

Carolyn Whitzman is a writer and housing policy researcher who lives in Ottawa, Canada. She is the author of Clara at the Door with a Revolver: the scandalous Black suspect, the exemplary white son, and the murder that shocked Toronto (UBC/ On Point Press, 2023) a riveting true-crime story centered on a courageous Black woman living in nineteenth-century Toronto who was charged with murdering the son of a well-do white family and the trial that followed. Her forthcoming book is Home Truths: Fixing Canada’s Housing Crisis (UBC/ On Point Press, September 2024).

Take it away, Carolyn!

What path led you to Clara Ford’s story? Why do you think it is important to tell her story today?

I first came across Clara Ford’s story while working on my PhD over 25 years ago, whose topic was the relationship between stereotypes, social conditions, and housing policies in Toronto’s inner city Parkdale neighbourhood over two centuries. One of the lies told about Parkdale when it was gentrifying in the late 20th century was that it had been a stable, middle-class, residential suburb when it was developed in the late 19th century. But all you needed to do was walk around the neighbourhood and look at old industrial buildings and tiny workers’ cottages to get a sense of social mix – and potential tensions between residents.

I turned to newspapers of the time and quickly came across the story of an impoverished mixed-race tailor, Clara Ford, who was accused of having murdered her former next-door neighbour, the son of a wealthy white manufacturer, in 1894. The more I read about the trial, the more I became obsessed with Clara. Clara was the first person I have found to be described as a “homosexual” in a North American newspaper. Her adventures as a cross-dressing traveller (who passed as a man but not as a white person) contributed to newspaper coverage that made her out as a ‘monster’, even as other newspapers painted her as a ‘tragic mulatto girl’ seduced by a boy almost half her age. Clara was also the first woman and second person in Canada to testify on her own behalf in a trial. She told a story of police harassment into a false confession, which was, remarkably, believed by a jury of twelve white men.

The themes of the book – working class Black life in Canada, sexual violence, police harassment, fake news – continue to be timely today, in a world of #BlackLivesMatter and #MeToo. I hope that Clara, like many women of her time and class only written about when she got into trouble, emerges from the book as a strong, brave, and very funny heroine of her own story.

What type of sources do you rely on in writing about a non-elite woman from the past?

What a good wonky question! I used two sets of primary sources and one set of secondary sources.

First off, I used newspaper articles. There were seven daily newspapers in Toronto at the time of Clara’s arrest and trial. They were engaged in a furious circulation war and cared very little about verified truth – the most important thing was a ‘scoop’. I see certain similarities with 24-hour news cycles and social media today.

My second set of sources was official documents of the time – census, directory, assessment, birth and death records… but Clara is remarkably absent from the official record. She only appears in the Canadian census once, as a 7-year-old in 1871 (although she was almost certainly close to 10 years old). There is no birth certificate for her or for her daughters, even though they were, again, almost certainly born in Canada. But I was able to track her white mother, Jessie McKay, through a set of falling down shacks and professions such as laundress and housecleaner.

The third set of sources are some excellent recent works on Canadian women’s history, Black history, legal history, and queer history that helped me put Clara’s story in context. Just about every trope that is still out there, particularly Angry Black Woman, was thrown at Clara. I kept on falling into rabbit holes. For instance, when Clara was acquitted, she joined a famous Black vaudeville troupe as a dancer (at the age of 33!). So I had to know more about late 19th century theatre and the development of the musical. My reference list is quite varied, because Clara lived a rich and complex life in several cities, always trying to stay under the radar.

What work of women’s history have you read lately that you loved? (Or for that matter, what work of women’s history have you loved in any format? )

There are a couple of women’s history books that have rocked my socks in recent years. One is Beautiful Lives, Wayward Experiments: Intimate Stories of Social Upheaval by Saidiya Hartman (Penguin, 2019). Like Clara, Hartman focuses on the lives of 19th century Black women in Philadelphia whose histories are only recorded because they encountered police and other authorities. Hartman writes about vibrant but forgotten women with a poetic sensibility that creates ravishing prose.

Square Haunting: Five writers in London between the wars, by Francesca Wade (Random House, 2021) focuses on a single street in the Bloomsbury neighbourhood, where relatively privileged and educated women in the early 20th century were trying to create new lives as independent writers. Wade’s sense of place, detail, and character lingers in my mind.

I also want to shout out to my favourite podcast, What’s Her Name, created by sister historians Katie Nelson and Olivia Meikle. They are gifted storytellers and I always enjoy travelling with them to re-discover cool women who have been forgotten!

[Pamela butting in here: I, too, am a big fan of the What’s Her Name podcast and the women who created it. In fact, they’ve participated in Three Questions and an Answer several times. You can find their Q & As , here, and here ]

A question from Carolyn: Can you tell me something surprising you have found about South Asian women’s history, please?

My most recent surprises from South Asian women’s history have not been large scale cultural issues, but stories about individual women who did not show up in my graduate student course work. One of my favorites of these is Raziya Sultan (1205-1240 CE), who was the only female ruler of the Delhi Sultanate in India—a Muslim empire that ruled over a large portion of India for several centuries prior to the Mughals.

Although she had several brothers, her father named her his successor to the throne. It probably will not surprise you to learn that neither her brothers nor the Muslim nobles in the sultanate were pleased with his choice. At his death in April, 1236, they attempted to put one of her brothers on the throne. He was described in the chronicles as being “incompetent”—which could mean many things. His mother was in control of the throne during his brief reign, which ended six months later when mother and son were assassinated.

Raziya then ascended to the throne. (It is unclear to me if she was involved in the assassination, but I would not be surprised if that were the case, family politics in medieval kingdoms, Muslim and otherwise, being what they were.) She was by all accounts an effective ruler, but the Turkish nobility, led by one of her brothers, rose up against her. She was defeated in 1240 and died soon thereafter, though accounts of her death vary.

A contemporary chronicler summed up her career with words that could be applied to that of many women who attempted to hold a throne at the time: “She was endowed with all the qualities befitting a king, but she was not born of the right sex, and so in the estimation of men all these virtues were useless.”

***

Want to know more about Carolyn Whitzman and her work?

Check out her Google scholar profile:

Follower her on the platform previously known as Twitter: @CWhitzman

***

Tomorrow it will be business as usual here on the Margins with a blog post from me. Then we’ll be back on Monday with an interview with Sarah Percy, author of Forgotten Warriors: The Long History of Women in Combat, a subject dear to my heart.

Talking About Women’s History: Three Questions and an Answer with Jane Draycott

Jane Draycott is a Roman historian and archaeologist, and the author of Cleopatra’s Daughter: Egyptian Princess, Roman Prisoner, African Queen. Over the last two decades, she has worked in academic institutions in the UK and Italy, and excavated sites ranging from Bronze Age villages to First World War trenches across the UK and Europe. She is currently Lecturer in Ancient History at the University of Glasgow. When she is not reading, writing, or thinking about Roman history and archaeology, she enjoys indulging her wanderlust by travelling to interesting places, playing computer games, cooking vegan food, practising yoga, and hooping. She lives in Glasgow with a tyrannical Norwegian Forest Cat named Magnus, and is currently renovating a dilapidated Victorian house.

Take it away, Jane!

Cleopatra Selene was a powerful figure in her time, but was largely overlooked until your book. Why do you think Cleopatra Selene and other powerful women of the past effectively disappeared from history?

Cleopatra Selene and other powerful women of the past have effectively disappeared from history for several reasons. The first is that they were genuinely excluded from most of the formal political and military positions of power that were responsible for shaping world history, and the second is related to that – while they certainly had informal political and military power, the ancient authors recording events preferred not to acknowledge that unless it offered an opportunity to pass comment (usually negative) on the men they were connected to. So during the Late Roman Republic, Roman women could not hold magistracies or imperium, so could not speak in the Senate, vote on or enact legislation, or raise and command armies, but they could wield a considerable amount of influence behind the scenes, hosting social events, lobbying other well-placed women to intercede with their men-folk and so on. And the third is that (predominantly male) historians from later periods have taken the ancient literary evidence largely at face value, and not questioned the fact that women don’t tend to appear in it except in exceptional circumstances. It’s only in the last few decades that historians have started deliberately searching for, and finding, the women. And while not Roman, client queens like Cleopatra and Cleopatra Selene suffered from the fact that it was, in the main, Roman authors writing about them, so they were judged according to Roman standards, and Cleopatra is excoriated because of her husband and Cleopatra Selene is ignored in favour of her husband. Finally, for many modern historians, they baulk at the relatively slim Greek and Latin literary evidence, and it doesn’t necessarily occur to them to look for other types of evidence such as documentary and archaeological evidence to supplement that. Academics can often get quite uncomfortable about stepping outside of their somewhat arbitrary disciplinary boundaries.

What overlooked woman from the ancient world would you most like to read a biography of, and why?

I would love to read a biography of Queen Amanirenas of Kush. She was Cleopatra VII’s contemporary and next-door neighbour, but unlike Cleopatra she was able to fend off the emperor Augustus’ Roman legions and their imperialistic ambitions to seize her kingdom and turn it into a Roman province. She was a one-eyed warrior who led her army into Egypt, sacked many towns, pulled down all the statues of Augustus that had been set up, and even took the head of one home to Kush and buried it under the steps of the temple to the goddess Victory in the capital city of Meroe, so she and her fellow Kushites could walk on it until two thousand years later when archaeologists discovered and excavated it. This head is now on display in the British Museum, a permanent memorial to rare Roman military defeat, and one masterminded by a woman at that. She is a less well-known but much more successful version of Boudicca.

What work of women’s history have you read lately that you loved? (Or for that matter, what work of women’s history have you loved in any format? )

The best work of women’s history that I have read recently is Emma Southon’s A History of the Roman Empire in 21 Women. Brilliantly researched and written, simultaneously managing to be erudite, filthy, and funny. No one writes about the Romans quite like Emma.

[For anyone who missed it, a mini-interview with Emma Southon ran on March 6. The title in the U.S. is A Rome of One’s Own. I’m currently reading it and agree with everything Jane said about it.]

A question from Jane: Who is your favourite female historical figure, and why?

I never know how to chose when asked this kind of questions. There are are many historical women who I admire or who fascinated me. But the answer that will make my editor, my agent, my publicist, and My Own True Love happy is Sigrid Schultz, the subject of my book that is coming out in August. She really was quite a gal. She was the Chicago Tribune’s Berlin bureau chief from 1925 to 1941 and one of the first reporters to warn American readers about just how dangerous the Nazis were. She was smart, courageous, and equal parts charming and prickly.

Now that I think about it, most of my favorite women in history could be described in similar terms.

***

Want to know more about Jane Draycott and her work?

Visit her website: https://drjanedraycott.co.uk/

Follow her on the platform previously known as Twitter: @JLDraycott

Follow her on Instagram: jane.draycott.

***

Come back tomorrow for three questions and an answer with Carolyn Whitzman, author of Clara at the Door with a Revolver: The Scandalous Black Suspect, the Exemplary White Son, and the Murder That Shocked Toronto

March 11, 2024

Talking About Women’s History: Three Questions and an Answer with Catherine McNeur

Catherine McNeur is an associate professor of history at Portland State University where she teaches courses on environmental history, the history of science, food history, and public history. Her first book, Taming Manhattan: Environmental Battles in the Antebellum City, won the American Society for Environmental History’s George Perkins Marsh Prize, the New York Society Hornblower Award, the Society for Historians of the Early American Republic’s James H. Broussard Best First Book Prize, and the Victorian Society of America Metropolitan Book Prize, as well as dissertation prizes from Yale University, the American Society for Environmental History, and the Urban History Association. Taming Manhattan looks at how loose hogs running through the streets, urban sanitation debates, and the location of green spaces were integral parts of the social unrest facing New York City at a moment of dramatic urbanization.

In her second book, Mischievous Creatures: The Forgotten Sisters Who Transformed Early American Science, she uncovers the lives of the entomologist Margaretta Hare Morris and botanist Elizabeth Carrington Morris. Though both sisters were at the center of scientific conversations and debates in the middle of the nineteenth century, they’ve long been written out of histories of science. Mischievous Creatures recovers their lives and work, while also investigating how these erasures occur.

Take it away, Catherine!

Credit: Andrea Lonas

What path led you to the Morris sisters? And why do you think it is important to tell their story today?

I never set out to write a book about the nineteenth-century scientists Margaretta Hare Morris and Elizabeth Carrington Morris. My plan had been to investigate the history of the much-hated (but sometimes loved) Tree of Heaven in American cities. However, while searching through the papers of a botanist who had written about that tree, I stumbled upon 250 letters written by someone named Elizabeth Morris. Googling her turned up very little at the time, not even a Wikipedia page, but I eventually learned that she was a botanist and her sister Margaretta was a renowned entomologist. Coincidentally, a month later I was doing some research in one of Harvard’s collections and fell across letters from Margaretta Morris. After reading through those letters, it was clear that Margaretta was struggling to be seen as a peer by other entomologists. “I have panted for the sympathy of someone who could appreciate my love of the science, and overlook my want of that learned love derived from books that are, generally speaking, out of woman’s reach,” she wrote. “The book of nature, however, has been widely spread before me, and countless hours of inexpressible happiness I have had in the study, there.”

I was captivated by Margaretta’s words and at the same time confused by the fact that no one had written about these women. Margaretta, after all, was one of the first women elected to the American Association for the Advancement of Science and the Academy of Natural Sciences. I wanted to know more about both sisters lives and also why we keep finding all these “hidden figures.” The fact that I stumbled across them was no mistake—many of their peers are similarly forgotten or erased and therefore hard to find in the archives. Recovering these stories, though, makes it possible to see that our current push to diversify the STEM fields has a long and complicated history where women were actually present at the very start of these professions.

Writing about historical figures like the Morris sisters requires living with them over a period of years. What was it like to have them as constant companions?

Writing biography really does require that you live with your subjects, doesn’t it? Delving into their scientific passions and discoveries, figuring out the romantic dramas affecting their lives, parsing the messages they sent to friends, even reading a neighbor’s gossipy diary that tracked their comings and goings—it all made nineteenth-century Philadelphia really come to life for me. These women, in many ways, feel very much like old friends now. This is perhaps especially true as they were my company (and my family’s company) during the COVID-19 lockdown.

I found, too, that they affected the way I experienced my daily life. Margaretta, for instance, adored what she called her “little friends the Insects” and never passed a spider web or a cluster of flies without stopping to see what she might find. On a neighborhood walk when I found myself engulfed in a cloud of tiny flies and began swatting them away from my face, I stopped to think that Margaretta might not have swatted them. Or as I was editing a chapter in a park and found a tiny beetle making its way across my page, I didn’t hurry to knock it away but instead spent some time closely observing it. In order to be conversant in Elizabeth research, I also ended up learning quite a lot about ferns and now I spend a lot of time reveling in all the maidenhair ferns, sword ferns, and licorice ferns I find on my neighborhood walks. By writing so passionately about entomology and botany, the Morris sisters transformed the way I, too, saw the world around me.

What unsung woman scientist from the past would you most like to read a biography of, and why?

One thing I learned quickly while doing research for this project is that there are so many little-known nineteenth-century women who were scientists and were as well-trained as many of the men who we know to be the “founding fathers” of various scientific fields. There are several women who should have biographies written about them, including Isabella Batchelder James, a botanist who studied the origin of plant scents among other subjects, and Sarah Coates Harris, another botanist who also lectured on women’s health and hygiene and fought for women’s rights in the mid-nineteenth century. One person who is really overdue for a new biography, though, is Dorothea Dix. She’s best known for her reform work with mental health asylums and her work managing nurses during the Civil War. However, she was also a scientist. She published articles in leading scientific journals about insects she had discovered and on all of her travels for work, she collected plant specimens and seeds and sent them to other botanists around the country. She was very much a scientist as well as a reformer, but that part of her life is little known. The biographies that do exist on her woefully underestimate both her and her work. She was a close friend of Elizabeth and Margaretta Morris and from what I’ve been able to find, she was likely in a romantic relationship with Margaretta. How I would love to read a book that truly takes her life and work seriously and sees her for who she was.

[Pamela butting in here: I spent a lot of time reading about Dorothea Dix when I was working on Heroines of Mercy Street and I didn’t read anything about Dix the scientist! Even the women whose stories are told are often reduced in the telling.]

A question from Catherine: Thank you so much for reading Mischievous Creatures and inviting me to participate in this wonderful exchange, Pamela! When I speak with readers at book events, I’m always delighted to hear what stood out to them or what they found relatable in the book. Was there any part that particularly captured your attention?

I am eternally fascinated by the ways in which women are erased from history, in this case by the process of creating scientific professions. Beyond that, I was intrigued by the fact that they were sisters, and the ways in which they worked together despite the differences in their fields of study and personalities. (Or perhaps because of those differences.) The comparison with the Blackwell sisters was unavoidable.

***

Want to know more about Catherine’s archival finds and writing?

Visit her website: https://www.catherinemcneur.com/

Follow her on Instagram: @catherine_mcneur_writer.

***

Come back tomorrow for three questions and an answer with historian and archaeologist Jane Draycott, author of Cleopatra’s Daughter