Pamela D. Toler's Blog, page 23

January 8, 2024

In which I finish reading Rin Tin Tin

Last Sunday I sat down and finished the last sixty pages of Susan Orlean’s Rin Tin Tin: The Life and the Legend. I had been reading it on and off over the last six months in small bites. Sometimes I put it aside because another book called my name. For one reason or another. (The Girls of Atomic City, for instance.) But often I put it aside because it was so intense that I needed a little break.

The intensity took me by surprise. I have no emotional attachment to Rin Tin Tin as a cultural icon. I am not old enough to have seen the The Adventures of Rin Tin Tin when it ran in prime time and have no memory of watching it in reruns on Saturday mornings. (On the other hand, I have fond memories of seeing an occasional episode of Sky King.) I finally pulled the book off my shelf, where it had sat unread for a decade, because My Own True Love and I were watching The Thin Man movies and he wondered which dog appeared in the movies first, Rin Tin Tin, Lassie, or Asta.*

Rin Tin Tin is alternately heartwarming and heartbreaking. Orleans begins with the story of a man’s love for a dog that he rescued from the battlefields in World War I. The book then moves through the world’s love first for films and then television programs that initially starred and later featured characters based on the original Rin Tin Tin. It ends with a handful of people who were obsessed with Rin Tin Tin, both as an animal and as an intellectual property, including legal battles over control of the dog’s name, image, and descendants.

Orleans sets the Rin Tin Tin story against a rich backdrop of related stories, including:

The development of German Shepherds as a working breed by by a German cavalry officer named Max von Stephanitz using various traditional German herding dogs in the early twentieth century.The changing use of dogs in film and television.The shift of dogs from outdoor working animals to pets, and the related growth of kennel clubs and obedience training.The Nazi idolization of German Shepherds as pure-bred “Aryan” dogs—and Hitler’s relationship with his own dogs.The recruitment of dogs for the United States Army’s K-9 Corps in World War II. (This was one of the points at which I had to set the book down for a while. I had learned about the K-9 corps previously when we visited historical Fort Robinson in Nebraska. Orleans looks at the story in more depth, which made it even more distressing as far as I was concerned.)Why Westerns were so popular after World War IIAs is often the case with Orleans books, she includes her experience of reporting the story, bringing the reader through the process.

In short, Rin Tin Tin is a masterful piece of storytelling.

*Rin Tin Tin by a long shot. He first appeared in silent movies, beginning in 1922. Also, as Orleans points out, Rin Tin Tin was a real dog who played fictional characters. Lassie and Asta were fictional characters in novels adapted for film. Not the same thing at all.

January 5, 2024

Helena of Egypt, whose story looks mighty familiar

Roughly a year ago, I wrote a post about Tamaris, a woman in the fifth century BCE who was the daughter of a painter and an acclaimed artist in her own right. Recently I learned of a similar story, courtesy of novelist Joanne Harris, who is running occasional posts titled “Women You Deserve to Know” on her Threads account.

Helena of Egypt was a painter in the fourth century BCE, active in the period after the death of Alexander the Great in 323 BCE.* Like Tamaris, she learned her craft from her father, an otherwise unknown artist named Timon. And like Tamaris, we know little about her. Our main source is Pliny the Elder (23/24-79 CE), who included her in a list of women artists in his Natural History. She also appears in a list of women named Helena in an encyclopedic work by Photios I of Constantinople (ca 810/820-893 CE), who probably got most of his information from Pliny..

According to both Pliny and Photios, Helena’s best known work was a scene of Alexander the Great’s victory over the Persian ruler, Darius, at the Battle of Issus. According to Photios, the Roman emperor Vespasian (r. 69-79 CE) held what was then an ancient painting, along with other spoils of war, in the Temple of Peace in Rome The painting is long lost, but a mosaic of the same subject found at Pompei is believed by some to be a copy of Helena’s work.

It turns out that Pliny was also Boccacio’s source for writing about Tamaris. In fact, he is our only source for women artists in ancient Greece and Rome. The list is small: Tamaris, Helena of Egypt, Aristarete, Iaia, Eirene, and Calypso. Pliny does not have much information on any of them, though he does suggest that all but one of them had a father who was also a painter. Working from details given by Pliny, later scholars have dated them from the sixth through the third centuries BCE—in other words centuries before Pliny wrote about them.

Perhaps inevitably, some modern scholars have suggested that one or all of them did not exist, for the same reasons that scholars have argued that various women warriors did not exist. *Sigh*

*A time of political chaos as Alexander’s generals, and his older half-sister Cynane (also a talented general), duked it out over the remains of his empire. But I digress.

January 2, 2024

What’s Up, Doc?

It’s a tradition here at History in the Margins that I kick off the year with a post about what I expect to work on and think about over the coming year. I’ve always thought of it as the blog equivalent of the coming attractions at a movie theater—minus the popcorn. (I realize this is a dangerous position. Not everyone loves watching the trailers for future movies. I do.)

This year I have no coming attractions to offer you, because at some level I have no idea what I’m going to do next.

I will still be writing, thinking and, hopefully, talking about Nazi Germany and women journalists as the publication date for The Dragon from Chicago draws near. (August 6!). Beyond that, I expect to flail around without direction: reading widely* and following rabbit holes wherever they take me. No musts or shoulds allowed. Quickly frankly, I’m looking forward to it—and I plan to take you with me.

Here’s to a New Year full of historical discoveries and lots of good books for us all.

*And randomly. The To-Be-Read piles are tall and varied. At the moment I’m reading books about the early movie industry, women in medieval Europe, and camouflage in World War II. Who know where they will lead me?

December 22, 2023

Silent Night: A Reprise

Earlier this month, My Own True Love and I began the holiday season with one of our favorite events: Songs of Good Cheer at Chicago’s Old Town School of Folk Music. For the last 25 years, a band of musicians and (now former) Tribune columnists Eric Zorn and Mary Schmich have led the audience in song. For the last 24 years, My Own True Love and I have been in that audience, accompanied by a changing cast of friends and family. The program each year includes both religious and secular holiday standards and less well known songs, some of which have become beloved over the years. There is always at least one Hanukkah tune and one song in Spanish. Every year, the audience sobs its way through a song by Mary Schmich titled “Gonna’ Sing.”*

Every year, the concert ends with “Silent Night.” This year, as we sang “Silent Night” I was reminded of our visit to Salzburg over Christmas several years ago. On our first full day in Salzburg we stopped at the Salzburg Museum to see a special exhibit celebrating the 200th anniversary of “Silent Night.”

Prior to seeing that exhibit, I had never thought about the historic context of the song, which a young Austrian priest named Joseph Mohr and the local teacher and organist, Franz Xaver Gruber,wrote in the small Austrian village of Oberndorf bei Salzburg in 1818.

Salzburg and the area around it had been under duress for several years. It was plundered by the French during the Napoleonic wars. Like much of Europe, it had suffered crop failures and food shortages in 1816 (“the year without summer”). That same year, after being shuffled back and forth between Austria and Bavaria, Salzburg was annexed by the Hapsburg monarchy, losing both its autonomy and its role as a regional capital. In 1818, the city suffered a major fire. No wonder Franz Gruber and Joseph Mohr wrote so longingly for peace.

I think we all share that longing this year.

*If you want to see the lyrics and hear the entire song, check out Eric Zorn’s blog, https://ericzorn.com/index.php/2023/12/12/gonna-sing/

* * *

I’m taking the rest of the year off. I’ll be back in the new year with historical tidbits for your enjoyment. Until then, have yourself a merry little celebration of he victory of light over the darkness in the tradition of your choice

December 19, 2023

The Girls of Atomic City

When My Own True Love and I decided to stop at Oak Ridge, Tennessee on our way to Atlanta, I immediately pulled Denise Kiernan’s The Girls of Atomic City: The Untold City of the Women Who Helped Win World War II out of the To-Be-Read pile where it had sat for far too long.* (Or maybe not. Perhaps books wait until their time comes.)

Kiernan explores the story of Oak Ridge through the experiences of the women who worked there, as well as those of women who played an important role in the development of nuclear fission outside of Oak Ridge. (I, for one, did not know that a German geochemist named Ida Noddack, writing in response to a paper by Enrico Fermi in 1934, was the first to postulate that the nucleus of an atom could be split by bombarding it with neutrons. Her male colleagues ignored and sometimes mocked her work.) Unlike most other works dealing with the “hidden figures” of science,** Kiernan does not limit her story to the women scientists, mathematicians and engineers who worked for the Manhattan Project. She also introduces us to secretaries, the women who operated the machines which produced enriched uranium,*** and one of the Black women who worked as cleaners in the facilities. In addition to the work itself, she talks about life in the “secret city” built deep in rural Tennessee. Mud that would suck a woman’s shoes off her feet. Housing shortages and security measures. The constant warnings about not asking questions and not telling anyone about your work. Social life in a city where the average age was 27 and men outnumbered women. She describes the racial discrimination that was literally built into the new city, and one woman’s clever efforts to make her life better than the rules allowed. It felt to me like Kiernan lost briefly her focus on women as the Manhattan Project drew to an end, with the final test at Los Alamos and the actual bombing of Hiroshima, but she quickly recovered.

The structure of the book is clever. Personal experiences alternate with sections that deal with the development of the Manhattan Project outside Oak Ridge and the science behind it. (Kiernan manages to make nuclear fission comprehensible to a non-scientist.) The compartmentalization of the book is deliberate, designed to echo the way information about the work was compartmentalized, with no one knowing how their job fit into a bigger picture, or even what the bigger picture was.

The Girls of Atomic City is a wonderful choice for anyone interested in the Manhattan Project or women’s roles in World War II.

*I swore to myself that when I was finished writing my book about Sigrid Schultz I was going to read some of the many non-fiction books I own that are not about World War II in general and women in World War II in particular. So far, that has not happened.

**How did we express this idea before Margot Lee Shetterly’s book?

***Now known as “calutron girls,” after the machines they operated, they were the Manhattan Project’s equivalent of Rosie the Riveter. Most of calutron cubicle operators were women from the middle south with a high school education. They worked eight hour days, in front of panels that allowed them to monitor the conditions that produced enriched uranium, though they did not know what the machines did.

December 13, 2023

Road Trip Through History: Oak Ridge Tennessee, aka Site X

This year My Own True Love and I spent Thanksgiving in Atlanta with family. Instead of joining the travel madness of flying over the holiday, we decided to drive. And since we were driving, we decided to turn the trip into a mini-historical road trip. (Does this surprise anyone?) Our goal: Oak Ridge, Tennessee, a “city” built from scratch as part of the Manhattan Project. We were, if you will pardon the expression, blown away.

Known as “Site X” in Manhattan Project documents, Oak Ridge was built specifically to house scientific facilities and the people who staffed them on land purchased by eminent domain, beginning in November 1942.* During the period when the Manhattan Project was active, Oak Ridge was the 5th largest city in Tennessee, but it did not appear on any map— though people in the surrounding region (especially those forced to leave their homes on short notice) certainly knew something was going on behind those fences. No one other than Oak Ridge staff and their families was allowed to live there. If you didn’t have a badge, you didn’t get in. (Even kids got badges when they turned 12.) The scientists and technicians at Oak Ridge developed ways to enrich uranium and ultimately produced the enriched uranium that fueled Little Boy, the bomb the was dropped on Hiroshima on August 6, 1945. Today Oak Ridge is home to a National Lab dedicated to nuclear science of all kinds, including disassembling nuclear weapons and safely storing uranium.

Oak Ridge is very conscious of its roots in the Manhattan Project. The city has four museums dedicated to its history and modern atomic science, as well as a plethora of historical markers throughout the town. (Signs directing tourists to the various museums and historical sites were simply labelled “Top Secret”—a playful approach that amused me greatly. )  We managed to visit two of the museums during our one day visit: the American Museum of Science and Energy, which is a Smithsonian affiliate, and the Children’s Museum of Oak Ridge, which houses an outpost of the National Park Service.

We managed to visit two of the museums during our one day visit: the American Museum of Science and Energy, which is a Smithsonian affiliate, and the Children’s Museum of Oak Ridge, which houses an outpost of the National Park Service.

The AMSE is divided into five major sections —the Manhattan Project, National Security, Big Science, Early Leadership and Environmental Restoration—plus a freestanding exhibit focused on Robert Oppenheimer. The exhibits as a whole were well-designed, with lots of interactive displays, but I must admit I began to flag the further we got from the history of Site X and the deeper we got into modern atomic science. The failure was mine. (Also, I get museum fatigue at about the two-hour mark no matter how interesting the displays. And also, it was two days before Thanksgiving and several local schools had scheduled field trips. ) The section dealing with the Manhattan Project itself consciously included displays dealing with the roles of women and people of color—and did not attempt to hide the discrimination faced by the Black workers at the site. One amusing display case included examples of unfamiliar technology used at the Oak Ridge facilities, including a rotary telephone.

Here were some of the things that caught my imagination:

The average age of residents and workers at Oak Ridge was 27.The story of mathematician and physicist Dr. J. Ernest Wilkins Jr (1923-2011): Wilkins entered the University of Chicago at the age of 13 as an undergraduate. He completed his PhD at 19, and began to teach mathematics at Tuskegee University. In 1944, he joined the University of Chicago Met Lab, where he worked with Arthur Compton and Enrico Fermi, researching nuclear fission. That fall, his team was transferred to Oak Ridge, but Wilkins was not able to go due to Jim Crow laws in Tennessee. Instead, he remained in Chicago, where he worked in Eugene Wigner’s Metallurgical Laboratory, where he helped design the nuclear reactors used at Oak Ridge.One of the facilities, K-25, was so big that people rode bicycles from one work area to another. “Watch for bicycles” signs were common throughout the building.The Children’s Museum of Oak Ridge is located in what was previously an elementary school built in 1944 to house the children who lived in the secret city—making it an exhibit as well as a container for the exhibit. It is a true children’s museum, with exhibits on a variety of subjects aimed at children with inquiring minds. (I was particularly taken by a hands-on exhibit about the lives of two fictional children in Appalachia in the summer of 1865. My Own True Love went straight for the stuffed polar bear.) Included in those exhibits is a two-part section on the Manhattan project that looks at Oak Ridge’s origins from a different perspective than that explored in the AMSE.

The first section, called the Oak Ridge Corridor, is a timeline titled “Difficult Decisions” that covers the length of one hallway. It puts the decision to build Oak Ridge into historical context, beginning with the Norris Act of 1933, which approved the establishment of the Tennessee Valley Authority—access to abundant electricity was one of the factors in choosing the Oak Ridge area as the home to Site X. The timeline dealt with questions of isolationism and the start of World War II as well as events touching directly on the Manhattan Project. One striking image was not directly related to Oak Ridge: a picture of Secretary of War Henry Stimson being blindfolded before he selected the first capsule in the Selective Services draft lottery—on October 29, 1940, a year before the United States entered the war.

The second section, another long corridor, focused on life in Oak Ridge when it was a secret city. This exhibit drew heavily on the amazing work of Ed Westcott, the site’s official photographer. The pictures of Oak Ridge residents at work and play make it clear just how young the average Oak Ridger was. They also make it clear the the “city” was an improvised place with strong overtones of the frontier.

The Children’s Museum is also home to the National Park Service’s visitor center: a small booth in the lobby. The ranger wasn’t on duty when we arrived, but I later had a chance to eavesdrop while he talked to a family about the Manhattan Project in general and Oak Ridge in particular. As usual, the park service did not disappoint.**

Quite frankly, I’m not sure I could have absorbed any more.

*For those of you who want the time line:

1939 German scientist Otto Frisch, working with his aunt Lisa Meitner (who is often left out of the story) produced the first theoretical interpretation of nuclear fission–which they named. Later that year, Albert Einstein and a number of other scientists wrote a letter to President Roosevelttelling him that the Germans had already started research on uranium and urging him to support similar research in the United States

The Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941. On December 8, the United States declared war on Japan. Three days latter, the Axis powers declared war on the United States.** Only then did the United States declare war on Germany and the other Axis powers.

The Manhattan Project was approved in August, 1942

** The National Park Service maintains a presence at three sites related to the Manhattan Project: Oak Ridge, Hanford, Washington, and Los Alamos, New Mexico. One down, two to go.

***

Travelers’ tip:

Dean’s Restaurant and Bakery, also housed in one of the original buildings, in this case the Jackson Square Pharmacy, is a classic meat and three. The docent at the ASME recommended it. I went with some hesitation because the photos on the website were not enticing. But we have had consistent good luck with museum staff suggestions, and this was no exception. The food was amazing. The portions are huge, so this is a good place to split a meal if you can agree. We could not. I also was unable to settle on one side, so I went with a meat and two, thus increasing the amount of food I left behind. The dessert menu looked excellent, but we were Too Full.

December 7, 2023

American Journalists and the “Grand Refrigerator”: A Small Pearl Harbor Story

Two days after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, the American government arrested hundreds of German, Italian, and Japanese citizens who were resident in the United States as enemy aliens. Among those arrested were German diplomats and journalists. In retaliation, the Nazis put all the American correspondents who were still in Germany under house arrest. A few days later, they were sent by train to the resort town of Bad Nauheim, along with American embassy and consular personnel and their families. The Americans were held there for five months while the American and German governments negotiated details for a personnel exchange. No mail was allowed in or out.

The Americans were interned in the Grand Hotel, a summer resort hotel which had been vacant since the beginning of the war and was by that time not so grand. The building, which was not designed for winter use, was unheated. The internees dubbed it “the Grand Refrigerator.” The food was inadequate. (Some internees used the breakfast rolls to caulk the leaky windows in their rooms, preferring to be a little warmer at the cost of a little more hunger.) —in all fairness, the conditions weren’t that different from those suffered by the average German at the time.

According to the internees’ own accounts, their biggest problem was boredom. They responded by creating “Bad Nauheim University.” With the motto “Education of the ignorant by the ignorant,” internees taught each other a variety of courses that included tap dancing, Sanskrit, bridge, self-defense, and philosophy. The most popular of these was a course in Russian history taught by diplomat and Soviet specialist George Kennan, who could not fairly be charged with ignorance of his subject.

George Kennan, ca 1947

They also held readings, musical performances, spelling bees, treasure hunts and mock trials. When the weather warmed up, they organized baseball games, using a bat whittled from a tree branch and a ball stitched together by an America doctor from a champagne cork, one internee’s pajamas, and a sock.

They didn’t play baseball for long. On May 12, 1942, the internees left Bad Nauheim on a train for Lisbon, where most of them boarded a Swedish ship bound for the United States. Thirty-two employees of the diplomatic service were sent directly to new assignments in Europe or Africa. They arrived in New York City on May 30th, 20 to 40 pounds lighter than they were on December 7, 1941

Perhaps not surprisingly, the Bad Nauheim tourist board prefers to emphasize another American who spent time there, in 1958:

December 5, 2023

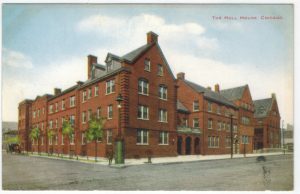

History on Display: The Jane Addams Hull House Museum

A few days ago, My Own True Love and I took a few hours off to visit a museum that’s been on our list for several years now: the Jane Addams Hull House museum. Jane Addams (1860-1935) and Hull House stand in the center of a Venn diagram of many of our interests: historical women who made a difference, late 19th and early 20th century reformers in general and the settlement house movement in particular, Chicago history, and the immigrant experience in America.

We were familiar with the basic story of Hull House: Jane Addams and Ellen Gates Starr were introduced to the concept of settlement houses, in which middle-class and upper-class reformers “settled” in group houses in poor urban neighborhoods, on a visit to London. On their return to the United States, they founded Hull House* in a densely populated, largely immigrant neighborhood in Chicago’s Near West Side. The settlement house offered a variety of social programs to neighborhood residents. All of which is true, but neither of us was prepared for the sheer scope of the Hull House project.

Hull House itself was only one of a multi-building complex that eventually filled an entire city block.** which is now part of the University of Illinois Chicago campus. Addams and Starr were the leaders of an extraordinary group of women—doctors, lawyers, artists, general shin-kickers—who made the world a safer, better place for women, children, blue collar workers, and immigrants. They helped lay the foundation for the field of occupational health and safety, helped pass laws against child labor, and published a report on conditions in their neighborhood that was the first to blame conditions in urban slums on economic systems rather than on the individuals who lived there. They pushed for an eight-hour work day and introduced art classes to the Chicago public schools. Addams won the Nobel Peace Prize in 1931, but not every one saw their actions as positive. Addams had an FBI file. The DAR dubbed her the most dangerous woman in America. And the “female führer” Elizabeth Dilling gave her a listing in her infamous Red Network.

At the complex itself, Hull House offered classes in art and music, technical skills, cooking, sewing, and English as a second language. They offered a wide range of services to the neighborhood, including a nursery and kindergarten so working women would have childcare, a public kitchen that served 60,000 meals a year, public baths,** an employment bureau, a clinic, an art gallery and performance space. The complex housed a branch of the Chicago Public Library and the Jane Club, which provided housing for single working women. It also produced its own electricity, and sold the excess power to its neighbors.

The museum tells the story well, with artifacts, photographs, and quotations. You are urged to sit at Addams desk. And, in what is one of the most unusual museum programs I’m aware of, the Jane Addams Bedroom Project, UIC staff, faculty and students are invited to sign up to take a nap in Addams’s bedroom—a practical expression of Addams’s believe that play and rest were important.

If you’re in Chicago, the Jane Addams Hull House Museum is well worth a visit. If Chicago is not in your future, a virtual tour is available at the museum website.

*Named after Charles Jerald Hull, the original owner of the quite astonishing Italianate-style house, built in 1865, that was the heart of the settlement. Since we are old-house nerds as well as history buffs, we were occasionally distracted by the building itself.

** The block was taken over by the University of Illinois Chicago. Only the 1865 building, where Addams lived and worked remains.

***Soon after Hull House opened, Addams learned there were only 3 bathtubs in the 1/3 square mile east of the building. She had 3 public baths built behind the settlement which gave almost 1000 people a month access to baths that were previously unavailable.

December 1, 2023

From the Archives: More About Salt

Speaking of salt, as I believe we were:

Anyone who sat through a third grade social studies lesson learned that Europe’s search for pepper changed the world. Prince Henry the Navigator, Columbus, and all that. But did you know that salt played an even bigger role in world history?

Unlike pepper, we can’t live without salt. It is as essential to life as water. Our bodies need it to digest food, transmit nerve impulses, and move muscles, including the heart.

When we were hunter-gatherers, the salt we needed came from wild game. (Sometimes wild game got the salt it needed by licking the places where we urinated. The circle of life can be weird.) As mankind settled and our diet changed, we had to find salt from other sources, not only for ourselves, but for the animals we domesticated.

In theory, salt can be found almost everywhere on earth. It fills the oceans, lies in rich veins in rock near the earth’s surface, and crusts the desert beds of long vanished seas. But until the Industrial Revolution, it was often difficult to obtain.*

The law of supply and demand is almost as dependable as the law of gravity. Because salt was hard to come by, it was valuable. It was one of the first international commodities and the first government monopoly.** Merchant caravans carried it across the most inhospitable places of the earth. Governments taxed it. Roman soldiers were paid in it.*** Mohandas Gandhi staged a protest around it.

The next time you pick up the salt shaker, show a little respect.

* The phrase “back to the salt mines” is rooted in that fact that mining salt was dangerous work, historically done by slaves or prisoners. As late as the mid- 20th century, both the Soviet Union and Nazi Germany used labor in the slave mines as punishment.

** China, ca 221 BCE.

***Hence the phrase “worth your salt”. Not to mention the word “salary”, which comes from the Latin word for salt.

Image courtesy of Carlos Porto at FreeDigitalPhotos.net

November 28, 2023

In which we visit a salt flat

When I thought about going on a food tour of Italy, I thought of wine, and pasta, and seafood, and olives and olive oil. I did not think about salt. And once I knew we were visiting a salt flat, it did not occur to me that our visit to the Saline Culcasi salt flats outside Trapani and their related museum would be the most overtly historical stop we would make in Sicily.

Trapani salt flats, with Archimedes screw

The salt marshes south of Trapani are one of the oldest salt-making sites in the world, first established by the Phoenicians in 1500 BCE, and continued by the Romans, the Byzantines, the Muslims and the Spanish. Salt from Trapani was shipped to the Hanseatic League in Bergen, from which it was traded throughout medieval Europe.

When Italy was unified in 1861, Sicilian salt manufacturers found it hard to market their product. The new Italian government, like so many others before them, imposed a salt monopoly that favored producers on the mainland. Trapani salt, once an important export, became a local product, used to cure tuna, preserve capers, and cure olives.* The island economy was not enough to sustain all the salt works, and most of them had been abandoned before the Italian government ended the salt monopoly in 1973.

The Culcasi family took a gamble and restored a salt marsh that had been rendered unusable by mud and flooding in the 1960s. They now operate the flats using traditional methods.** Salt pans are divided by earthen dikes, which are punctuated by stone windmills. The windmills, which were introduced to the process in the eighth century, serve two purposes. They power Archimedes screws*** that move water from salt pans at different levels. They also use wind energy to grind dried salt crystals.

Mound of drying salt protected by tiles

* Food tour!

**They also have a mechanical facility that produces commercial salt on a much larger scale.

***Invented in third century BCE, as you may recall, by a resident of Sircusa. This article from Scientific American gives an excellent description of how the Archimedes screw works: Lift Water with an Archimedes Screw