Pamela D. Toler's Blog, page 22

February 16, 2024

In the Realm of a Dying Emperor

Women’s History Month is barreling toward us and I am happily working on bringing you another March full of mini-interviews with people who are doing interesting work in women’s history. In the meantime, I’m sharing some of the books that I’ve rediscovered in the process of finding room on my office shelves for the books I used in writing The Dragon From Chicago. (The danger with this is the temptation to re-read the books as I go. Which wouldn’t be a problem if it weren’t for all the as yet unread books piled throughout my office.)

Next up, In the Realm of a Dying Emperor by East Asia scholar Norma Field

Long, long ago, when I was a graduate student, I team-taught three sections of a four-section continuing education course called “Asia and the Middle East” for the University of Chicago. I covered South Asia, the Middle East, and occasionally South East Asia. My co-teacher, Robert LaFleur, a brilliant and creative scholar who combines anthropology and history in his study of Chinese history and culture, covered China, Japan, and occasionally Korea. Over the course of the five years that we taught the course, I read everything he assigned—a fascinating dive into cultures and history that I knew little about that was the rough equivalent of an undergraduate major in East Asian studies. (Minus term papers, exams, and language requirements.)

In the Realm of a Dying Emperor, published in 1991, was one of those books. It was, by intention, a solid kick in the cultural assumptions. Emperor Hirohito had died in 1989. Norma Field, the daughter of an American soldier and a Japanese woman, was in Japan in the year leading up to his death. She witnessed the nation’s vigil over the dying emperor and its uncritical, formalized exaltation of his life after his death. In In The Realm of a Dying Emperor, Field sets that exaltation and the “national amnesia” which made it possible against the stories of three Japanese who dissented against the cultural hegemony that dictated the response to the emperor’s death in the prior two years. An Okinawan supermarket owner burned the Japanese flag in protest against Japan’s treatment of Okinawans. A widow sued the state to prevent the Shinto deification of her husband, a member of the Self-Defense Force who died while officially on duty, though not on the battlefield, claiming that it was an infringement of her religious rights as practicing Christian. The mayor of Nagasaki, also a Japanese Christian, raised a furor, and exposed himself to death threats, by stating that the emperor bore some responsibility for Japan’s role in World War II and consequently for the nuclear attacks on Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

Field does not simply tell their stories, she examines the public response to their actions and the roots of their actions in their minority status. She interweaves their stories with her own experience as “one of them war babies” growing up in Japan in the 1950s.

My memory of the book is that it was a compelling account of a society with fractures it did not acknowledge. If you’ve read it, I’d love to hear what you thought.

February 12, 2024

From the Archives–Samurai: The Last Warrior

I’m currently embroiled in proofreading the endnotes for The Dragon From Chicago. It’s a headache-inducing job, but it is the one part of the book in which no one can catch the errors except the writer. (Probably the person who made one of them. ) Instead of hoping I pick up speed and can squeeze out a new post, here’s post that ran in 2013 for your amusement.

John Man combines travelogue, history and social commentary in Samurai: The Last Warrior, using the story of Saigo Takamori, popularly known as the “last samurai”, as his central focus.

In 1877, Saigo led a hopeless rebellion against the Japanese government. Six hundred samurai armed with traditional sword and bow fought the government’s newly trained modern army in an effort to reverse the westernizing changes of the Meiji Restoration. When all was lost, Saigo committed ritual suicide; the institution of the samurai died with him. Three years after Saigo’s death, the government against which he rebelled erected a monument honoring him as a great patriot.

Man uses Saigo’s story as a lens through which to consider the history of the samurai, Japan’s rapid transformation from a feudal society to a modern one, and the ways in which samurai culture colors Japanese society today. He offers detailed explanations of both familiar elements of samurai culture, such as ritual suicide, and less familiar subjects, such as formalized sexual relationships between men. Man himself is never far from the page, whether comparing traditional samurai education with that of a British public schoolboy, visiting a class where a toned-down version of samurai-style sword fighting is taught, discussing the samurai in the context of other “honor cultures” (think street gangs), or explaining Darth Vader’s samurai roots.

Samurai is an engaging look at the final days of a military elite: a great choice if you’re interested in the the story of the last samurai or the lasting influence of these warriors on Japanese culture.

February 9, 2024

Lords of the Horizon

Women’s History Month is barreling toward us and I am happily working on bringing you another March full of mini-interviews with people who are doing interesting work in women’s history. In the meantime, I’m sharing some of the books I’ve rediscovered in the process of finding room on my office shelves for the books I used in writing The Dragon From Chicago. (The danger with this is the temptation to re-read the books as I go. Which wouldn’t be a problem if it weren’t for all the as yet unread books piled throughout my office.)

Next up, Lords of the Horizons: A History of the Ottoman Empire by Jason Goodwin

Lords of the Horizon was published in 1998, and I probably bought my copy soon after that. It is by far the most readable of the accounts of the Ottoman Empire that I have accumulated over the years.* Goodwin is an accomplished guide through the six centuries of Ottoman rule, from the empire’s origins in a nomadic people on the Eurasian steppes through its heydays in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries to its eventual end in 1922. His prose style is lush and lyrical.. His narrative style is an idiosyncratic, non-linear blend of vivid anecdotes and deft historical summary–occasionally requiring the reader (i.e. me) to stop for a moment to figure out where she is in the bigger arc. He writes brilliantly about the Ottomans at war, but his focus is on the creation and maintenance of an empire that was multicultural at its heart.** As far as I was concerned, occasional moment of chronological confusion (Mine, not Goodwin’s.) were worth it—a fair exchange for moments of startling insight.

Goodwin went on to write a series of mystery novels set in mid-nineteenth century Istanbul, the first of which The Janissary Tree, won an Edgar. Also well worth reading, both for the story and as an introduction to the world of the Ottoman empire on the edge of decay. (Time for a re-read, I think.)

*At first I said “collected over the years,” but that suggests a more focused approach than I can claim.

**I am eternally fascinated by multicultural societies.

###

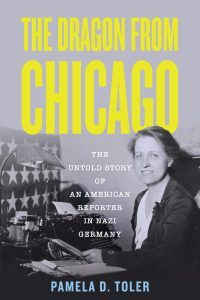

Apologies to those of you who hit the link to pre-order a signed copy of The Dragon for Chicago and found that it had gone bloooey. (I know at least one of you did—otherwise I wouldn’t know it had failed. Thank you, Dr. Wetmore.) It worked at the time I published the last two posts. Honest.

Here is a new link, which looks less crazy than the old link and is currently working: https://www.semcoop.com/dragon-chicago-untold-story-american-reporter-nazi-germany (Please let me know if it fails.)

A reminder of how this works: There is a space at the bottom of the order page to add special instructions. Request a signed copy there, and specify how you want the book to be signed.

You can also preorder the book wherever you usually buy books. Thank you.

February 6, 2024

Reveille in Washington

Women’s History Month is barreling toward us and I am happily working on bringing you another March full of mini-interviews with people who are doing interesting work in women’s history. In the meantime, I’m sharing some of the books that I’ve rediscovered in the process of finding room on my office shelves for the books I used in writing The Dragon From Chicago. (The danger with this is the temptation to re-read the books as I go. Which wouldn’t be a problem if it weren’t for all the as yet unread books piled throughout my office.)

Next up, Reveille in Washington, 1860-65 by Margaret Leech

This is a much more handsome cover than the edition I own.

Reveille in Washington was published in 1941. It became an immediate best seller, won the Pulitzer Prize for History in 1942,** and has remained a classic work of Civil War history ever since. If you know a serious Civil War history buff, they probably have a copy on their shelves.

Reveille in Washington is not an account of battles and generals. Instead Leech focuses on the war through the lens of the capital, looking at its politics and its people.

The book opens with a character sketch of the American army’s aging. overweight commanding general, Winfield Scott— the chapter title notes “The General is Older than the Capital”—who was emblematic of the army at the outbreak of the Civil War. The book is larded with similar portraits, often witty and always insightful, of characters who peopled Washington over the course of the war: General George McClellan, Frederick Law Olmstead, Andrew Carnegie, Clara Barton, Walt Whitman and Louisa May Alcott among others. Leecch claimed that she tried to keep Lincoln out of the book because it was the story of Washington. Late in the writing, she realized “that was like doing a book about the disciples and not mentioning whose disciples they were.” She had to go back and insert Lincoln into her story.

But the primary character in the book is Washington, D.C., itself, which was in many ways a frontier town despite its location. Leech describes it as “an idea set in wilderness.” In 1861, the city was unfinished, filthy, and famously corrupt. One Union soldier, who arrived to guard Washington in the first days of the way grumbled that the city was “hardly worth defending, except for the éclat of the thing. Reveille in Washington is at heart the story of how the city shaped the conduct of the war and was shaped by the war in turn, from an unfinished administrative backwater to the true center of federal power. It is also a thumping good read. Leech wrote several novels before she turned to history and it shows. She knows how to tell a story.

*Leech won a second Pulitzer in 1960 for In the Days of McKinley, which also won the Bancroft Prize in American History and was a finalist for the National Book Award. She remains the first person and only woman to win two Pulitzer Prizes for History. ** It is perhaps not coincidental that Leech was married to Ralph Pulitzer, whose father had established the awards. Nonetheless, the fact that the playing field is never entirely flat does not change the fact that Reveille in Washington is a great book.

Leech was also a sharp-tongued member of the Algonquin Round Table, which came as a surprise to me. Turns out that more women were members of the vicious circle than I realized: https://algonquinroundtable.org/6-women-you-didnt-know-were-members-of-the-algonquin-round-table/

**Barbara Tuchman won two Pulitzer Prizes for General Non-Fiction, for The Guns of August in 1963 and Stillwell and the American Experience in China in 1971. But I digress.

###

I mentioned before The Dragon From Chicago is now available for pre-order wherever you get your books. If you want a signed copy, you can order it from my neighborhood book store, the Seminary Coop Bookstore at this link: There is a space at the bottom of the order page to add special instructions. Request a signed copy there, and specify how you want the book to be signed. (I’m afraid there’s going to be a certain amount of “My Book, My Book!” going forward. Sorry, not sorry.)

February 2, 2024

Girl Sleuth

Several weeks ago, I mentioned that I am in the process of putting away my research materials for The Dragon From Chicago. I said then that it is always harder than I expect and that remains true. My efforts are turning my office into a pit of despair. Putting one thing away requires moving another three.

This is particularly true in the case of the bookshelves. I shelve my books alphabetically by author’s last name. Adding a single book requires shuffling books, sometimes across several shelves, to open up a spot. I have not yet resorted to stacking books vertically, but I suspect the time will come.

There is an upside to all this, familiar to anyone who has packed or unpacked books. As I struggle to move books from the project bookshelf to the permanent bookshelves I handle books I haven’t thought about for a long time. It is impossible to do this without stopping to read a little bit and remember why I enjoyed them, or why they mattered to me. It inevitably slows down the process, but it is a great delight. (I wish I could report that this resulted in a few books moving to the give away pile. No such luck.)

Over the next few weeks, I’ll be sharing some of the books I’ve re-discovered with you. First up, Girl Sleuth: Nancy Drew and the Women Who Created Her by Melanie Rehak.

I read Girl Sleuth when it first came out in 2005.* When I pulled it off the shelf last week as part of the great shelving project, I was tempted to dive back in and read it again. I may yet.

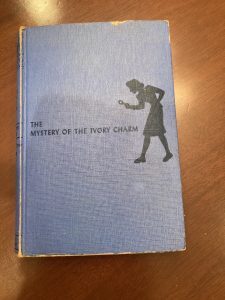

Rehak knows who her audience is: the generations of women who have read and loved the Nancy Drew books since the first four books were published in 1930. (Not to mention those who watched at least one movie and a television series.) Rehak is a member of that audience. And so am I. The first Nancy Drew book I ever read, my mother’s copy of The Mystery of the Ivory Charm (1936), still holds a place on my bookshelves.** For many of us, Nancy Drew, with her roadster, her gal pals,**** her great clothes, and her unending stream of adventure, was an icon, if not actually a role model.

(I must admit, when I pulled it off the shelves to take this picture, I was tempted to read it again. )

In Girl Sleuth, Rehak tells the story of how the Nancy Drew books moved from a pulp series to a foundational text of American girlhood. It turns out that publisher Harriet Stratemeyer Adams and journalist Mildred Augustine Wirt Benson, the original women behind “Carolyn Keene”—the equally fictional author whose name still appears on the covers of the Nancy Drew, almost 100 years and 600+ volumes later—were just as interesting as the titian-haired girl detective. For at least this Nancy Drew fan, Benson turned out to be almost as much of a potential role model as her most famous creation.

Time to put Rehak back on the shelves and see what book catches my attention next.

*Hard to believe it was almost twenty years ago.

**The downstairs shelves that hold fiction, not the ones in my study.

***Far more interesting characters than her stalwart boyfriend, Ned Nickerson. (The fact that I remember his name is evidence of how deeply engrained the books are in my brain.)

*Clears throat nervously*

While you’re here, I have a piece of news: The Dragon from Chicago is now available for pre-order wherever you get your books. If you want a signed copy, you can order it from my neighborhood book store, the Seminary Coop Bookstore at this link: There is a space at the bottom of the order page to add special instructions. Request a signed copy there, and specify how you want the book to be signed.

January 30, 2024

A Photojournalist You Never Heard Of

In the lull between Christmas and New Year’s a high school classmate of mine, and regular reader of this blog, reminded me of the woman who was a photographer for our hometown paper, Betty Love.(1) The name rang a bell, but I knew nothing about her. I had decided to take the last ten days of the year off, so I had time to take a little dive down a rabbit hole.(2) I’m so glad I did. Love’s career was both singular and emblematic of the careers of many women journalists of the mid-twentieth century. I had no idea.

Love was an art teacher in Springfield ,Missouri’s elementary and junior high schools in the 1930s. In 1941, she took what was supposed to be a temporary job replacing the cartoonist at the Springfield News and Leader. (Given the timing, I presume the cartoonist she replaced had volunteered for World War II , though none of the sources say that.) Not surprisingly, her cartoons focused on the realities of wives and children on the home front, an unusual perspective for political cartoonists at the time. (4)

She was still the “temporary” cartoonist four years later, when the paper’s photographer, John Reading McGuire, was drafted. The paper’s editor, perhaps counting on Love’s artistic talent, handed her McGuire’s camera and told her she was now the photographer. She quickly taught herself the technical skills she needed to do the job, including how to develop film in the newspaper’s darkroom.

Love was the paper’s photographer for three decades, from 1945 until her retirement in 1975.

She was a photographer for a local paper, but her work was known beyond the Missouri Ozarks. One of her photographs helped change the rules governing news photography. In 1948, she was assigned to get a picture at the federal courthouse, where two prisoners were being brought in under the custody of federal marshal Fred “Bull” Camfil. Camfil told her she couldn’t take the picture. Love told him she had a first amendment right to do so. Camfil made the mistake of saying “The constitution be damned.” When Love continued to take pictures, the marshals threw blankets over the prisoners. Love’s photograph and Camfil’s foot-in-the-mouth comment made the wires. The incident led to a ruling that federal marshals and their deputies could not prohibit photographers from taking pictures of federal prisoners on the public way outside of a courthouse.

Printed in the Springfield News and Leader, December 7, 1947

Love was one of the first women newspaper photographers, a pioneer of the use of color photography in daily newspapers a charter member of the National Press Photographers Association, and one the original inductees into the Missouri Journalism Hall of Fame.

I was fascinated by Love’s story, but it raised a question for me. How many women like her were there, working as hard-nosed journalists at smaller papers at the same time that Sigrid Schultz and a handful of other women were making their names in big city papers? And how do you find them? *****

If you know of a woman who worked in your local paper in the mid-twentieth century as a reporter or photojournalist, I’d love to know.

(1) Thanks, Tracy!

(2) Who am I kidding? I would have gone down that rabbit hole regardless. I always do.(3)

(3) My new motto in this regard regard comes from Zora Neal Hurston: “Research is formalized curiosity. It is poking and prying with a purpose. It is a seeking that he who wishes may know the cosmic secrets of the world and they that dwell therein.” (With a hat tip to historian and biographer Ray Boomhower, who recently shared this quotation.)

(4) At this point I drifted down a secondary rabbit hole on women political cartoonists and began to build a bibliography. Because I had a thought.

(5)Actually, now that I think about it, I have an idea or two about that. Hmmm.

January 26, 2024

Broad Strokes

In 2021, I read an article by art historian Bridget Quinn titled “What Should We Call the Great Women Artists?” I was already struggling with the questions of what to call Sigrid Schultz in the book I was working on.* I was fascinated by Quinn’s argument and taken with her voice. I immediately added her to the list of people I wanted to contact for my series of Women’s History Month mini-interviews the following March.** (You can see her interview here.)

Almost two years after that interview, I finally read Broad Strokes: 15 Women Who Made Art and Mad History (In That Order).

Here’s the short version of what I have to say: Wow!

Here’s the short version of what Quinn has to say: “The careers of the fifteen artists that follow run the gamut from conquering fame to utter obscurity, but each of these women has a story, and work, that can scramble and even redefine how we understand art and success.”

In the introduction, Quinn tells the story of how she came to realize that women artists had existed, even though few of them appeared in the Big Fat Art History Book that was used in almost every art history class taught in the United States in the last 50 years, H.W. Janson’s History of Art. She continued with the journey that led her from that revelation to the book in my hand.

The fifteen essays that follow are dazzling. Quinn is erudite, witty, and passionate. She places each woman in not only her art historical context, but her larger historical moment. By the second essay I had lugged my copy of Janson off the shelf so I could look at the art work Quinn references. (Yes, I recognize the irony.) When Jansen failed me, I turned to Google. She traces major themes across the essays: the recurrence of missing mothers and artist fathers, the similar challenges the women faced across the centuries, the difficulty of finding information on the artists. More, Quinn sets each woman within the context of her own intellectual and emotional journey, telling us how each artist entered her life and what it meant to her at the time. Her analysis is consistently insightful. Her interaction with each work is personal, and inspiring.

As you can tell, I am a fan. If you are interested in smart writing, women’s history, or looking at art from a different perspective, this one’s for you.

*It took me another two years to make a decision.

**I’m running the series again this March, with a fascinating line-up of creators working in the field of women’s history. Don’t touch that dial.

***

Bridget Quinn has written a full-length biography of one of the women she explores in Broad Strokes. Portrait of a Woman: Art, Rivalry and Revolution in the Life of Adélaïde Labille-Guiard will be released on April 16. I can hardly wait.

January 22, 2024

American Journalists and the Great War

One of the challenges of writing history is deciding where the story starts. For me that not only means deciding where I begin telling the story, but how much of the backstory I need to understand. The short answer is, a lot. I am never comfortable making broad generalizations based on other people’s broad generalizations.

For The Dragon From Chicago, I spent a lot of time learning about the history of foreign and war correspondents. It had not dawned on me before I began working that overseas press bureaus as we know them were, like so much of life in the mid-twentieth century, an outcome of World War I. If I was going to understand the conditions under which Sigrid Schultz worked, I needed to understand how journalists covered the Great War.

I started with very general books on the subject, most notably Philip Knightley’s the First Casualty: The War Correspondent as Hero and Myth Maker from the Crimea to Iraq.* Knightley’s book is a solid, accessible introduction to the subject. If I were a different kind of writer I could have stopped there.

I’m so glad I didn’t. If I had, I might not have discovered Chris Dubb’s two excellent books on American journalists in the Great War.

American Journalists in the Great War: Rewriting the Rules of Reporting (2017) is a deep dive into the experience of American journalists who reported on the war in Europe in which Dubbs argues that they redefined war coverage. (For what it’s worth, I agree.) He looks at the journalists who covered both fronts before America entered the war in April 1917, including those who attached themselves to the German army. He outlines the development of an accredited news force attached to the American Expeditionary Force (A.E.F.), in greater depth than Knightley. He follows the experiences of individual journalists, in the Balkans, in Russia, in the trenches of the Western front. My only quibble with the book is a personal one: only two of the World War I correspondents who later reported from Berlin made an appearance. I would have loved to see them through another historian’s eyes.

Dubbs briefly discussed women who managed to report on the war in American Journalists in the Great War. He covered the subject in greater depth in a second book, An Unladylike Profession: American Women War Correspondents in World War I (2020). Women weren’t allowed to become accredited war correspondents attached to the AEF, but some gained credentials as “visiting correspondents” for magazines and others made their way to Europe with no credentials at all. Dubbs covers the stories of more than thirty women who reported on the war. Their shared assignment was to cover the “woman’s angle” of the war. As a group they stretched that definition to include much more than their editors intended. (My personal favorite, mystery novelist Mary Roberts Rinehart, was the first journalist to visit the front line trenches.) An Unladylike Profession was less useful to me than his more general book, but I found it absolutely fascinating, for obvious reasons.

I give both books a big thumbs up for anyone interested in the history of journalism, the First World War, or kick-ass women.

* “The first casualty when war comes, is truth.” Senator Hiram Johnson. 1917. (In case it isn’t obvious from that quotation, Johnson was not a fan of the United States getting involved in the Great War. He was also a major player in the United States’ decision not to sign the Versailles Treaty and a leader of the isolationist movement in the period leading up to the Second World War, though he hated being referred to as an isolationist.)

January 15, 2024

From the Archives – Three Mothers: How the Mothers of Martin Luther King Jr., Malcolm X, and James Baldwin Shaped a Nation

Anna Malaika Tubbs is the author of The Three Mothers: How the Mothers of Martin Luther King Jr., Malcolm X, and James Balwdin Shaped a Nation. She is also a Cambridge Ph.D. candidate in Sociology and a Bill and Melinda Gates Cambridge Scholar. After graduating Phi Beta Kappa from Stanford University with a BA in Anthropology, Anna received a Master’s from the University of Cambridge in Multidisciplinary Gender Studies. Outside of the academy she is an educator and DEI consultant. She lives with her husband, Michael Tubbs, and their son, Michael Malakai.

Take it away, Anna!

What inspired you to write about these women?

I have always been passionate about correcting the erasure of Black women. When I started my PhD I knew I wanted to bring attention to Black women who had been wrongfully forgotten. We often hear the saying that “behind every great man is a great woman,” a saying that really bothers me, because most likely in such cases that woman is right beside the man, if not leading him. So I wanted to think about things differently and introduce the woman before the man. I believe mothers are some of the most underappreciated and unseen people in society and I felt it was time to honor them with the attention and credit they deserve. With all of this in mind, I dove into researching mothers of famous Black men. When I came across Alberta’s, Berdis’s, and Louise’s stories that were filled with nuance, diversity, as well as similarities and intersections as a result of the closeness in their birthdays as well as their famous sons’ birthdays, I just knew I had to dive deeper and share their names with the world. Their lives offer guidance and encouragement for Black women today, they show us different ways to be women, Black women, Black mothers, activists, educators, and much more. They remind us how difficult the world can be while also showing us ways to actively change it.

Who are some of your favorite authors working in women’s history today?

I have so many, but I’ll list a few!

Isabel Wilkerson – what she was able to do with The Warmth of Other Suns and now Caste is deeply inspiring. Her research is crucial and her ability to translate years of work into beautiful narratives that allow us to understand difficult concepts easily is something I try to emulate.

Patricia Hill Collins – her extensive sociological work on all aspects of Black womanhood and Black feminism over decades provides the basis of so many projects, interventions, and policies that impact our lives. You simply cannot do research on anything concerning Black women without engaging in something Patricia Hill Collins produced.

Melissa Harris-Perry – She is the kind of public intellectual I hope to become. She is brilliant and she uses her work to inspire change within, but more importantly beyond, the Ivory tower. She reminds all Black women of our worth and the treatment we deserve even if we’ve been denied it time and time again in the United States. Sister Citizen is one of my all-time favorite books.

How can your book help us better understand the civil rights movement as well as our current political/social climate?

At the center of The Three Mothers is a discussion of the dehumanization of all Black people. Motherhood is about creation, the giving of life, and this role becomes even more powerful in communities that are denied humane treatment on a daily basis. We as a Black community are continuing a long-fought struggle for our humanity, dignity, and worth to be recognized. This book, by focusing on Black motherhood, acknowledges that fight and shows how despite the many ways that our humanity has been denied in our nation, we have continued to find ways to humanize ourselves, give life, and move our country forward.

The Three Mothers provides a perspective of a century of U.S. history through the eyes of Black mothers. Alberta King, Berdis Baldwin, and Louise Little were born within six years of each other, the first was born in the late 1890s, and the last of the three to die, passed away in the late 1990s. The book is a lesson on the way history has impacted the current fight we find ourselves in from the perspective of identities we do not highlight enough. We have much to learn from the generation before our revered civil rights heroes, we have much to learn from Black women, and we have much to learn from Black mothers.

Question for you – Who would you say are women warriors of today?

In Women Warriors, I concentrated on women for whom battle was not a metaphor. By that standard, some of the most amazing modern women warriors are the Kurdish women who fought against Isis. They are the subject of a new book by Gayle Tzemach Lemmon, The Daughters of Kobani. I loved her previous book, Ashley’s War and I’m looking forward to this one.

* * *

Want to know more about Anna Malika Stubbs and The Three Mothers?

Check out her website: https://annamalaikatubbs.com/

Follow her on Twitter: @annas_tea_

* * *

Come back tomorrow for three questions and an answer with historical novelist Diana Giovinazzo.

January 11, 2024

175 Days of Bad News

I am slowly packing away my research materials for The Dragon from Chicago.* It is always harder than I expect. I have small stashes of material that I did not file at the time because I wasn’t sure where they should go. I stumbled across a stack of draft chapters that I never put away, probably because the project boxes were already full. (A problem I have not resolved in the interim.) And somehow I need to find room in the permanent bookshelves for the books currently stored on the rolling project bookshelf**—not an easy task.

In the course of dealing with the project bookshelf, I realize that there are a number of very good books that I never shared with you. Luckily, it’s never too late for a book review or two.

I think of The Last Winter of the Weimar Republic by Rüdiger Barth and Hauke Friederichs and Hitler’s First Hundred Days by Peter Frisch as a set, bookending the moment when Hitler became the German chancellor in January 1933.

The two books are different in structure and tone.

Barth and Friederichs take the reader day by day from November 17 1932 through January 30 1933. Each day opens with two or three newspaper headlines and is told in short segments that tell the story from different perspectives—a technique the authors describe as a “documentary montage.” Their goal is the let the story emerge without commentary based on hindsight. The result is powerful. (They also include a useful timeline at the end, which helped me keep a handle on the chronology of events at a time when things were moving very quickly.)

Hitler’s First Hundred Days has a more traditional narrative structure but is just as powerful. Frisch looks closely at the speed and brutality with which the Nazis built the structure with a terrifying combination of violence and parliamentary action—and the absence of resistance with which their actions wer met. His purpose is to understand how “a total fascist state that in January 1933 was highly contested rather improbable was widely accepted and broadly realized one hundred days later.”

Together, The Last Winter of the Weimar Republic and Hitler’s First Hundred Days give a reader a clear sense of the steps that allowed Hitler to take power and how the Nazis consolidated their position once they were in power. It is a chilling picture.

*Coming August 6 to your favorite purveyor of books. Which feels simultaneously like a long time from now and tomorrow.

**In theory, I can pull it next to my desk so that I can grab books as I need them. In reality, by the time I need to grab books , it is already too heavy to move. Besides, standing up and walking across the room multiple times a day gives me a moment to bend and stretch—always a good thing.