Pamela D. Toler's Blog, page 25

October 20, 2023

Beatrice Warde: “First Lady of Typography”

Those of you who read my previous post on Books Across the Sea have already been introduced (very briefly) to American writer and typographer Beatrice Warde (1900-1969).

Like many writers, I have opinions about type fonts,* and I was fascinated to learn about the changing world of typography in the first half of the twentieth century and a woman who made a name for herself in what I am sure you will not be surprised to learned was then a male-dominated field.

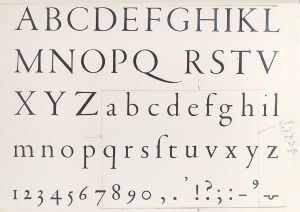

Warde began researching typefaces and printing history as an assistant librarian for the American Type Founders company, where she worked from 1921 to 1925, when she married a typographer and moved to London. She entered the professional world of typography under a male pseudonym in 1926, with an article titled “The Garamond Types, Sixteenth and Seventeenth Century Sources Considered”** written under the name Paul Beaujon. The article appeared in The Fleuron, a magazine devoted to typography, and earned “Paul Beaujon” a reputation as a scholar of typography. It also earned “him” a job offer as the editor of The Monotype Recorder, published by the Lanston Monotype Corporation.

Monotype did not revoke the offer after Warde revealed that she was a woman–which could well have happened. She worked for Monotype first as editor of the magazine and later as the publicity manager until her retirement in 1960, making her one of the few women working in typography at the time. In her years at Monotype, she championed both the intelligent revival of historic typefaces and the work of contemporary typeface designers. In the process, she helped shape the face of modern printing. She believed that type should not call attention to itself : “Type well used is invisible as type.” But that didn’t mean that typographic decisions weren’t important: “Type, the voice of the printed page, can be legible and dull, or legible and fascinating, according to its design and treatment.”

One of her longest lasting contributions to the world of printing was a broadside, printed in 1932 to showcase one of Monotype’s new fonts:

This is a

Printing Office

Crossroads of Civilization

Refuge of all the arts

against the ravages of time

Armoury of fearless truth

against whispering rumour

Incessant trumpet of trade

From this place words may fly abroad

Not to perish on waves of sound

Not to vary with the writer’s hand

But fixed in time having been verified in proof

Friend, you stand on sacred ground

This is a Printing Office

Her words were cast in bronze and stand at the entrance to the United States Government Printing Office, a tangible reminder of the power of the printed word.

*So many ways to be a nerd.

**For those of you who are not font nerds, Garamond is a group of serif-style typefaces based on the work of a sixteenth-century Parisian engraver named Claude Garamond.

*** This blog post led me down a lot of rabbit holes that I ultimately cut, but I couldn’t resist sharing this one: A fleuron, literal a leaf, is a typographic element used to divide paragraphs, differentiate items on a list, or as ornament. (A much nicer term than a bullet list. Also known as a printers’ flower, or “horticultural dingbats.” If I can figure out how to do it, horticultural dingbats may replace asterisks on occasion in this blog.****

****So far, I have failed in this attempt.

October 17, 2023

Books Across The Seas

Rationing, food shortages, and the clever ways people got around them are major themes in books about the British home front in World War II, fiction and non-fiction alike. Packages from friends in the United States made life easier for a lucky few. (C.A.R.E. packages came after the war.) I recently learned that books from the United States were another response to war time shortages.

Early in the war, Britain banned the import and export of non-essential goods to free up shipping space for necessities. Printed books were on the non-essential list.

Beatrice Warde was an American writer and typographer who lived and worked in London. Even the quickest dip in the research rabbit hole makes it clear that she deserves a blog post of her own, but for now it is enough to say that she was deeply involved in London’s printing world and was no doubt aware of the ban on the transatlantic book trade earlier than most readers.

In 1940, with the help of her mother, May Lamberton Becker,* the literary editor of the New York Herald Tribune, Warde arranged for friends and acquaintances who had reason to travel to Britain to carry single copies of important new American books to London in their hand luggage—where they competed for space with other scarce items such as coffee, sugar, or stockings. A similar selection of books published in Britain were sent to the United States in the same way. It was the beginning of a cultural and literary movement known as Books Across the Sea.

The original set of books that Ward had smuggled, seventy in all, in were displayed in the office of the Americans in Britain Outpost of the Committee to Defend America by Aiding the Allies, also known as the White Committee after its leader, newspaper editor William Allen White.** Books were soon seen to be goodwill ambassadors,*** and a formal organization was created to carry on Warde’s work with poet T.S. Eliot as its president. By 1944, the organization had send some 2,000 books to London and 1,600 books to New York.

The organization continued to operate under the aegis of the English-Speaking Union until 1984.

*Another possible blog post subject. If there is one thing I’ve learned in the last four years, it is that lots of women were doing interesting things in the first half of the twentieth century. More than I ever imagined.

**The White Committee was devoted to supporting pro-British policies in the United States that would help Britain in its war against Nazi Germany, essentially the polar opposite of organizations founded by Elizabeth Dilling. But that’s another story.

*** Duh.

October 13, 2023

Cultural Currency–Nazi-style

In my last post, I wrote about Sigrid Schultz’s columns titled “From Across the Sea” and the fact that they gave me close up glimpses of life in Nazi Germany. One column that caught my attention in particular was the plan to issue “Kulturemarks” which appeared in her column on March 4, 1938–eight days before Germany marched into Austria.

Wages in Germany had remained stationary. The cost of basic necessities had increased at the same time as the quality of those goods had decreased. Not surprisingly, Schultz told her readers, workers were grumbling. Labor officials were unwilling to raise salaries because consumers would be tempted to buy more things if they had more money, which would increase “temporary shortages”* of food, textiles, and other goods. (Go figure.)

The Ministry for Public Enlightenment and Propaganda** came up with a plan. Instead of increased wages, the government would distribute Kulturemarks which could be spent on entertainment, sporting events, and culture but not on food, clothing, or other necessities. Circuses, but no bread, as it were. It was in some ways a very Nazi approach: the celebration of German Kultur was a common element of pan-Germanism in all its variations.

Another article by Schultz ran the same day. It summed up the big picture nicely: “Assurances of friendship with America, efforts to come to an understanding with England, hidden threats against Austria, and impending rupture of the stagnating German-Russian diplomatic relations marked today’s political developments in Nazi Germany.

In short, big stuff was getting ready to go down. Kulturemarks weren’t even on the radar as far as American readers were concerned. And yet, and yet, the Austrian Anschluss was only the first step in Hitler’s drive east in search of more space, food, and raw materials, which he believed were needed to make greater Germany, well, great. Kulturemarks were intended to distract German workers from the shortages behind that drive.

I don’t know if the plan came to fruition. I haven’t been able to verify it in any of my Big Fat History Books about Nazi Germany or any of my go-to online sources. Even if it didn’t, the fact that such a plan was under discussion is revealing.

*The quotation marks are hers, not mine.

** A name that I find darkly comic.

October 10, 2023

“From Across the Sea”

In November , 1933, the Chicago Tribune began running an occasional column titled “From Across the Sea” featuring reported think pieces by correspondents of the Tribune’s Foreign News Service. The column ran on the editorial page along with letters to the editor and other columns such as the whimsical “A Line O’Type or Two.”* Sigrid contributed 78 essays to the column, between December 20, 1933 and October 30, 1938.

In her hands, the column provided an alternate perspective on, and occasionally a sly-counterpoint to, straight news stories from Berlin. In her first column “from across the seas,” Sigrid discussed Nazi efforts to replace the Weimar Republic’s extensive social safety net with a reputedly voluntary relief scheme for winter relief**–an indirect way to talk about the scale of unemployment and hunger in Germany. Her final column disguised a discussion of the Nazi use of radio propaganda under a blanket of “tech talk” about cheap radios and radio loudspeakers in public places.

In the years in between, Sigrid reported on big stories from the relative safety of the editorial page. How censorship had crippled the German newspaper industry. Germany’s attempt to create synthetic oil to reduce its dependence on foreign oil—and the importance of oil in developing a mechanized military. The government’s call for amateurs to provide the politic police with the news and information “needed for its [Germany’s] protection.”

Sometimes she opened a column with a statement or statistic from a German publication as a way of introducing a discussion of a potential dangerous topic. For example, she opened an early column by warning Americans about the dangers of inflation, gave a vivid picture of German life during the hyperinflation of 1923, and discussed the long term consequences for German society—including a culture of hatred directed against Jews and Poland.

In other columns, she used a human interest story to provide background—or give a twist— to a straight news story that appeared elsewhere in the paper . For example, on January 11, 1936, the Tribune ran a news item was the headline “Hitler Assures Diplomats He is in good heath; that same day in “From Across the Sea,” Sigrid ran a profile on the German doctor who had operated on Hitler’s throat after the Führer began having trouble making his radio broadcasts.

Sigrid also used the column to report on smaller issues that might not otherwise have found their way into the Tribune’s pages as a news item, adding an editorial spin about why they mattered. These were a sharp-penned version of the often-over-looked“mailers”: pieces that didn’t have immediate news priority and thus could be sent to Chicago by mail rather than using the quicker, more expensive cable service. Such stories included the publication of a five-volume Encyclopedia of German Superstition, the Nazis’ rejection of Christianity, and the development of “Nazi dances” appropriate to “the new German spirit.” ***

I found some of these smaller stories especially intriguing. They gave me up-close glimpses of Nazi Germany that don’t appear in Big Fat History Books.

* As I mentioned in a previous post, the column’s title was a truly dreadful pun on the linotype machine, a typesetting machine that revolutionized publishing. First introduced in 1866, it powered the production of daily newspapers around the world through the 1970s.

**Not exactly “a thousand points of light.” Thirty thousand welfare offices were manned by unpaid members of the Nazi party and the program was funded by “voluntary” deductions of two percent of a workers’ income taken directly by his employer.

***She described the style as a mixture of folk dancing and “our grandfather’s fashionable counter dancing” (think a more refined relative of the Virginia reel)—in other words, not the “degenerate” dances inspired by imported American jazz.

October 6, 2023

Elizabeth Dilling: “The Female Führer”

On of my favorite accounts to follow on the site formerly known as Twitter,* On This Day She –which just made its last post– previously made an important point at the head of its feed:

“A reminder: we do not ‘celebrate’ all the women we include in @onthisdayshe . Equal history means including those with whom we profoundly disagree. If the grim men are in the history books, we have to acknowledge the grim women too.”

A case in point: Elizabeth Dilling (1894-1966).

Dilling was a prominent member of the pro-fascist extreme right in the United States during the 1930s and 1940s. According to professor Glen Jeansonne, who studied Dilling and her allies, she considered herself a “professional patriot,” defending flag and faith against an array of threats that included Jews, communism, the New Deal, and the liberal Democrats who supported New Deal policies.

She found her passion as a political activist of the Red-baiting variety on a month-long tour of the Soviet Union with her husband Albert in 1931. She came back an avid anticommunist—a position that would be absolutely understandable if it hadn’t developed into being “anti” a lot of other things. (See above) Over time, her hatred for communism grew into sympathy for the the fascism of Hitler and Mussolini, which she saw as a bulwark against Soviet Russia. A Nazi newspaper gave her the nickname “the female Führer.” She called herself “Little Poison Ivy.”

Back in the United States, she threw herself into an intensive “study” of communism—the kind of study where you learn what you expected to find—and built a name for herself as an anti-communist speaker. Sometimes reaching audiences of several hundred at a time, she spoke to church groups, rotary clubs, women’s groups, most notably the DAR, and veteran’s organizations, including the American Legion.

In 1932, she founded an anti-communist organization, the Paul Reveres, that grew to 200 local chapters. Beginning in 1933, she spent long days researching and cataloguing groups and individuals whom she believed were threats to the United States

In 1934, encouraged by fellow anti-communist Iris McCord of the Moody Bible Institute, Dilling self-published The Red Network: A “Who’s Who” and Handbook of Radicalism for Patriots, a 352 page book that relied heavily on the idea of guilt by association that Senator Joseph McCarthy would use so effectively in his own Red Hunt some years later. Roughly half of The Red Network consisted of lists of more than 450 organizations that Dilling described as “Communist, Radical Pacifist,** Anarchist, Socialist [or] I.W.W. Controlled” and more than 1300 “Reds” and their affiliations, including Jane Addams, Albert Einstein, Sigmund Freud, Mahatma Gandhi, Senator Robert M LaFollette, and Eleanor and Franklin Roosevelt, The book went into eight printings and sold more than 16,000 copies by 1941. Organizations such as the KKK, and the German-American Bund gave away thousands more.

She was involved in an attempt, led by retailer Charles Walgreen, to close her former alma mater*** the University of Chicago as a communist institution. Henry Ford, who was anti all the things she was against and willing to put his money where his hatred was, hired her to investigate communism at the University of Michigan. (She also investigated UCLA, Cornell, and Northwestern—finding all of them to be hotbeds of communism and a menace to the youth who studied there.)

She was a leader of the movement of women’s groups who opposed the United States entering the war in Europe on “maternalist” grounds, arguing that war was the antithesis of motherhood.**** They supported their argument with right-wing, anti-Roosevelt, anti-British, anti-communist and antisemitic rhetoric. She was arrested for disorderly conduct in 1941, after she led a sit-down strike outside the office 84 year-old senator Carter Glass of Virgina. Glass was not a fervent New Dealer by any standard, but he was appalled by the behavior of Dilling and her followers. He called on the FBI to investigate the women’s groups and publicly stated that “I likewise believe it would be pertinent to inquire whether they are mothers. For the sale of the race, I devoutly hope not.” (For the record, Dilling had two children.)

Many of the groups continued to oppose the war after the attack on Pearl Harbor, unlike the better known America First Committee.

In 1942, Dilling and 27 other anti-war activists were indicted under the Alien Registration Act. (This is why she crossed my path. Sigrid Schultz served as a witness for the government.) They were accused of holding pro-fascist views—which Dilling certainly did—and with being Nazi propaganda agents. Dilling was charged with plotting to incite a mutiny in the American Armed forces and setting up a Nazi state. Charges were dismissed in 1946, in large part because the trial had dragged on so long that the second judge who presided over it declared it a travesty of justice.

*And yes, Twitter is problematic. I am exploring other social media sites. But nothing to date has quite captured the things that made the app so satisfying. If you are looking for me elsewhere, I am currently on Bluesky as @pdtoler.bsky.social, on Instagram as pamelatolerauthor and on Facebook as, well, me. (Full disclosure, my Instagram account is mostly about my cat and food. I aspire to do more with it.)

** Apparently not the same thing as isolationists, which she approved of, at least in the context of WWII.

***She attended for three years but left without graduated

****They were not the first to oppose mother and warrior. I explore this idea in some depth in the first chapter of Women Warriors.

America First; right wing extremist; pro-Germany; anti communist

October 3, 2023

From the Archives: Reading My Way Through Roman Britain, Pt. 3

The places I hang out on line are having a lot of fun theses days with the question of how often men think about the Roman Empire. The answer apparently being, a lot. (Really?) I have no idea who started it, or why. But it’s a natural for history nerds being nerdy. It has spawned fun memes, and lots of playful silliness at a time when some of us need that.

I don’t have an answer. (And I haven’t asked My Own True Love the question.) But for those of you who are interested in thinking about the Roman Empire for at least a short while, I’m re-running this series that I orginally posted in 2015. With any luck, by the time the series has run its course I will have finished these endless revisions and we can go back to thinking about women journalists, Nazi Germany, fascism in general, and whatever else grabs my history nerd attention.

British journalist Charlotte Higgins (It’s All Greek To Me) was always fascinated by the classical world, but that fascination didn’t extend to Roman Britain. She thought of Britain as an unglamorous outpost on the edge of the Roman Empire–an opinion shared by most Romans of the time-. A visit to Hadrian’s Wall changed her mind. Under Another Sky: Journeys In Roman Britain is the story of her search to understand Rome’s 360-year occupation of Britain and its influence on the British sense of history and identity

Higgins travels across Britain in an unreliable camper van in search of traces of ancient Rome. She walks the tourist-friendly Hadrian Wall and tracks down the remains of Londinium through modern London with the help of a map published by the Museum of London. She visits small museums, major museums, and a tourist trap called Iceni Village. She interviews archaeologists, museum curators, farmers turned innkeepers near Hadrian’s Wall, and a full-time Roman centurion who appears at museum events and school programs. She considers the unexpected cache of Roman “postcards” known as the Vindolanda writing tablets, an influential eighteenth-century forgery of a Roman text, and re-imaginings of Roman Britain by later generations of British antiquarians, poets, military engineers and composers, including Benajmin Britten’s soulful Roman Wall Blues, composed for a radio play by W. H. Auden.

Under Another Sky weaves together Britain’s history and contemporary landscape into a complex and fascinating whole that is part travelogue, part history, and wholly charming.

September 29, 2023

From the Archives: Reading My Way Through Roman Britain, Pt. 2

The places I hang out on line are having a lot of fun theses days with the question of how often men think about the Roman Empire. The answer apparently being, a lot. (Really?) I have no idea who started it, or why. But it’s a natural for history nerds being nerdy. It has spawned fun memes, and lots of playful silliness at a time when some of us need that.

I don’t have an answer. (And I haven’t asked My Own True Love the question.) But for those of you who are interested in thinking about the Roman Empire for at least a short while, I’m re-running this series that I orginally posted in 2015. With any luck, by the time the series has run its course I will have finished these endless revisions and we can go back to thinking about women journalists, Nazi Germany, fascism in general, and whatever else grabs my history nerd attention.

Guy de la Bédoyère’s The Real Lives Of Roman Britain: A History of Roman Britain Through The Lives of Those Who Were There is not a narrative history of Roman Britain. (De la Bédoyère has already written several versions of that narrative.) It is instead an attempt to look at the 360 years of Roman occupation in terms of human experience rather than “the generalities of military campaigns, the antics of emperors, the arid plains of statistical models and typologies of pottery, the skeletal remains of buildings, and theoretical archaeological agendas.” [p.xi]

The attempt is not entirely successful due to a problem that de la Bédoyère identifies early in the book as “visibility”. There is surprisingly little evidence, physical or textual, about the Roman experience in Britain and even less about individuals–often no more than a name and a hint. (Sometimes not even a name. One individual, known as the “Aldgate-Pulborough potter”, is recognizable only by the distinctive incompetence of his work.) Consequently, much of the book is devoted less to the lives of Roman Britain and more to an evaluation of the available evidence.

In lesser hands, this close analysis of inscriptions, clay tablets, pottery shards, and, yes, the skeletal remains of buildings could be as dry as the dust from which they are taken. De la Bédoyère considers each bit of evidence with wit and imagination, leading the reader with him on the path of discovery rather than simply providing her with his conclusions.

September 26, 2023

From the Archives: Reading My Way Through Roman Britain, Pt. 1

The places I hang out on line are having a lot of fun theses days with the question of how often men think about the Roman Empire. The answer apparently being, a lot. (Really?) I have no idea who started it, or why. But it’s a natural for history nerds being nerdy. It has spawned fun memes, and lots of playful silliness at a time when some of us need that.

I don’t have an answer. (And I haven’t asked My Own True Love the question.) But for those of you who are interested in thinking about the Roman Empire for at least a short while, I’m re-running this series that I orginally posted in 2015. With any luck, by the time the series has run its course I will have finished these endless revisions and we can go back to thinking about women journalists, Nazi Germany, fascism in general, and whatever else grabs my history nerd attention.

“Hadrian’s wall at Greenhead Lough”, with thanks to Velella and Creative Commons

Thanks to the luck of the book-review draw, I recently ended up reading two books on Roman Britain back-to-back.* The two books are very different. Guy de la Bédoyère’s The Real Lives of Roman Britain is an attempt to look at the period of Roman occupation in terms of individual human experience–a frustrating endeavor because there is surprisingly little evidence. Charlotte Higgins’s Under Another Sky: Journeys In Roman Britain is a more personal attempt to understand the Roman occupation and its continuing influence on Britain’s sense of history and identity–think VW bus and hiking Hadrian’s Wall.** Both were fascinating; taken together they gave me a rich picture of a period I mistakenly thought I knew something about.

My reviews of both books will appear in coming posts. In the meantime, here are some of the things that surprised me:

Rome controlled Britain for 360 years, assuming a floating definition of control. That’s almost twice as long as Britain ruled India.Britain was a hotbed of revolt against Rome for most of those 360 years. I knew about Boudica, the female ruler who led an uprising against the Romans in 61 CE.*** And because I knew about Boudica I was vaguely aware that the Druid stronghold at Mona (modern Anglesey) was believed to harbor dangerous rebels. But I knew nothing about, for example, the Gallic Empire, a short-lived break-away regime founded by Marcus Cassianus Latinus Postumus *** in 259 CE in Britain’s northwestern-provinces. Postumus and his successors borrowed all the attributes of a “real” Roman emperor, including coins minted in their names, consulships, assassinations and usurpations.I knew that the pre-Roman Britons left no written history. That what we know about them comes from Roman accounts and archaeological finds. (Some of which are pretty spectacular.) I didn’t realize that what we know about the experience of the Romans themselves in Britain is also based on relatively limited evidence. For instance, the primary source for Julius Caesar’s not particularly successful invasions of Britain in 55 and 54 BCE are Caesar’s own accounts, which are certainly contemporary but by no means unbiased.There’s a lot to learn out there.

* Usually this happens in response to a major historical anniversary, but unless I’m missing something this time it was just because.

**And yes, I am now thinking about hiking along Hadrian’s Wall.

***Thank you, Antonia Fraser

****Which does, in fact, mean posthumous. The name was given to a man born after his father’s death. Who knew?

September 22, 2023

From the Archives: When Paris Went Dark

Another post from the past, in this case 2014, related to the stuff I’m working on today. New stuff soon, I promise.

When Nazi troops marched into Paris in June, 1940, the city surrendered without firing a shot.*

In When Paris Went Dark: The City of Light Under German Occupation, 1940-1944 , historian Ronald C. Rosbottom explores face-to-face interactions between occupiers and occupied, the effect of the Occupation on daily life in Paris, its psychological and emotional impact on Parisians and its legacy of guilt and myth.

Drawing from official records, memoirs, interviews and ephemera, Rosbottom tells a story that is more complicated than simple opposition between courage and collaboration, though he offers examples of both. He discusses the fine line between survival and collaboration, the distinction between individual acts of resistance and the Resistance and how occupiers and occupied utilized the hide-and-seek possibilities of Parisian apartment buildings. He considers the act of waiting in line both as an illustration of the difficulties of everyday life and as a replacement for forbidden political gatherings. Above all, he describes the Occupation as gradual constriction of Parisian life within ever-narrowing boundaries.

Rosbottom does not limit his discussion to the Parisian perspective. Some of the most interesting sections of When Paris Went Dark deal with the German experience in the city, a complex mixture of tourism, conquest, envy and isolation. His account of Hitler’s early-morning tour of the capital soon after its surrender is particularly illuminating about the Nazi Party’s ambivalence toward cities in general and Paris in particular.

When Paris Went Dark is an important and readable addition to the social history of World War II.

*I will admit with only the slightest embarrassment that when I think “Nazi occupation of Paris” the images that come to mind are straight out of Casablanca. That will probably never change. Because putting pictures in our heads–accurate or not–is one of the things great art does.

September 19, 2023

From the Archives: Word with a Past–Parchment

One of these days I’m going to come out the other side of this book, honest. Luckily I have 10+ years of blog posts to draw on in the meantime.

I had forgotten all about this one from 2013.

*****

For hundreds of years papyrus was the principal material on which books (or at least hand-copied scrolls) were written. Since it could only be made from the pith of freshly harvested papyrus reeds, native to the Nile valley, Egypt had a monopoly on the product–and a potential monopoly on the written word.

In the second century BCE, the kingdoms of Egypt and Pergamum* got into an academic arms race.

The library at Alexandria had been an intellectual power house since it was founded by King Ptolemy I Soter in 295 BCE. Ptolemy set out to collect copies of all the books in the inhabited world. He sent agents to search for manuscripts in the great cities of the known world. Foreign ships that sailed into Alexandria were searched for scrolls, which were confiscated and copied.**

Thirty years later, King Eumenes of Pergamum founded a rival library in his capital. Both kingdoms were wealthy and the two libraries competed for sensational finds.

In 197 BCE, King Ptolemy V Epiphanies took the rivalry to a new level by putting an embargo on papyrus shipments to Pergamum. The idea was that without papyrus, scholars in Pergamum could not make scrolls and therefore could not copy manuscripts. The Pergamum library would be crippled.

In response, Pergamum turned to a more expensive, but more durable, material made from the skin of sheep and goats. We know it as parchment, from the medieval Latin phrase for “from Pergamum”.

Librarians are a resourceful lot.

* “Where?” you ask. Here:

As you can see, not a small place.

** Alexandria kept the originals*** and gave the owners the copies. Piracy of intellectual property is not new.

*** According to Galen, they were catalogued under a special heading: “books of the ships”.