Pamela D. Toler's Blog, page 27

August 12, 2023

From the Archives: Semicolon

Some recent back and forth with a long time blog reader about paper, punctuation and other writerly subjects inspired me to go back to Cecilia Watson’s Semicolon, which I reviewed in August, 2019. Here’s what I said then. I am pleased to report that the book is just as good as I remember.

If you’ve read much of my writing, you have probably figured out that I am not a member of the esteemed Semi-colon Haters Society. Personally, I find it a evocative and flexible piece of punctuation. So when I had a chance to review Cecelia Watson’s Semicolon: The Past, Present, and Future of a Misunderstood Mark for Shelf Awareness for Readers, I grabbed it.

It did not disappoint.

On the surface, Watson’s Semicolon is a rollicking history of the punctuation mark that people love to hate. She grabbed my attention immediately with the fact that not only had someone invented the semicolon—something that had never occurred to me—but that we know who he was.*

Watson places the semicolon’s creation in the broader context of Italian humanism, when punctuation was still experimental. She considers the fate and creation of other punctuation marks. She discusses the semicolon’s role in a debate over Massachusetts’s liquor laws in the early 20th century–and the larger question of the impact of punctuation on judicial rulings. She outlines arguments used by semicolon-bashers. She reviews historical attempts to define the proper use of the semicolon.

She also examines the different ways in which five skilled and very different writers–Raymond Chandler, Henry James, Herman Melville, Rebecca Solnit and Irving Welsh–use the semicolon in their work. Watson concludes that the semicolon “represents a way to slow down, to stop, and to think.” Alternatively, it can allow a writer to speed up the pace of her text. In short, the role of the semicolon is to measure time in the pursuit of meaning.

Watson’s vision of the semicolon’s purpose points toward a subversive argument that runs alongside her history of its journey from clarity to confusion. She argues that it is impossible to untangle the history of the semicolon from the history of grammar rules and guidebooks. Looking at grammar guidebooks through the lens of the slippery semicolon, she comes to the conclusion that the written rules of language are a barrier to communication rather than a support.

Well worth the read for history buggs and grammar nerds alike.

*Venetian scholar Aldus Manutius (1449-1515). He is best known for producing high-quality, inexpensive pocket-sized editions of Greek and Latin classics—a new idea at the time. In other words, a book lover’s hero.

August 8, 2023

Florence Mendheim: Librarian Against the Nazis

Florence Mendheim (1899-1984) was the daughter of German-Jewish immigrants had moved to the United States in the 1880s and still had close contact with their family back in Berlin. She worked as a librarian in the Washington Heights branch of the New York Public Library for 25 years, from 1919 to 1944. In 1933, she learned that Rabbi J.X. Cohen of the American Jewish Committee wanted volunteers who were not obviously Jewish to infiltrate the growing American Nazi movement, she did not hesitate. Cohen provided her with a fake address, a fake name, and a Nazi party pin. For the next five to six years, she spent her evenings spying on American Nazis.

Under the pseudonym Gertrude Mueller, she attended meetings and rallies of the pro-Nazi group Friends of New Germany and its successor organization, German American Bund. She gathered names, took notes as a secretary for the groups, and accumulated pro-Nazi and antisemitic propaganda and literature. Sometimes at the end of the meeting, another participant would offer to drive her home, making that fake address valuable indeed. It was terrifying. She could never be sure whether the offer was made as an act of politeness or because someone suspected her.

She used two other pseudonyms as well as Gertrude Mueller. She signed her reports to the American Jewish Committee with the random initials KQX. She used the name Anna Hitler as a cover for doing research on Hitler at various academic institutes under the guise of doing genealogical research.

Mendheim appears to have quit spying in 1938 or 1939. The need for such work ended several years later. When United States entered the war at the end of 1941, they cracked down on pro-Nazi organizations, perhaps with help of reports from Florence Mendheim and others who had been brave enough to spy on pro-Nazi meetings.

August 5, 2023

From the Archives: A Brief History of the Pencil

In yesterday’s newsletter (1), I went down a research rabbit hole, looking for the difference, if any, between using blue pencils and red pencils as an editing tool. (Plus the plus pencil’s use by military and authoritarian censors, which is the place where I leaped into the rabbit hole.) In the process, I went back to to this brief history of the pencil, which originally ran in February, 2020.

(1) For those of you who missed the memo, I write a newsletter in addition to this blog. It come out roughly twice a month. I generally write about thinking and writing about history, with an occasionally foray into stray bits of research. It’s also the first place to find news about my books, speaking gigs, etc.

If that sounds like your cold glass of lemonade, you can subscribe here: http://eepurl.com/dIft-b I’d love to see you there.

And now, back to our regularly scheduled program:

A giant pencil that I received as a Christmas present in Nuremberg. Thanks, Christopher!

One of the unexpected things I learned during our visit to Nuremberg over the holidays is that the city was the home to the first mass-produced graphite lead pencils, beginning in 1662.

Before we visited Nuremberg, I hadn’t given the history of pencils much thought.* In fact, the only piece of pencil history that I knew was that Thoreau invented a better pencil, and then got bored with the whole thing and went off to do something else. But I would have been hard pressed to tell you what made Thoreau’s pencil better. (We’ll get there in a moment.)

As those of you who have hung around here on the Margins for a while know, I can’t resist tracking down the story behind a bit of history trivia. Here’s some of what I found:

The roman stylus is the immediate ancestor of the modern pencil: a thin metal rod that was used to make a light mark on papyrus. Some styluses were made of lead, which why we still call pencil cores leads even though they have been made of graphite ever since the stylus became a pencil.In fact, graphite is the reason styluses became pencils. In 1564, someone discovered a large graphite deposit in Borrowdale, England. Graphite makes a darker mark than lead, but it is too soft and brittle to use without something to hold it. At first, people wrapped graphite sticks in string, but eventually someone inserted a graphic stick into a hollow piece of wood. Poof! A pencil.The new industry/craft of pencil making was transformed in Nuremberg. As I’ve mentioned before, the Nuremberg council kept tight control over craft processes in the city. Pencil-making was seen as a two-step process, requiring craftsmen from two different trades to create a single pencil: a lead cutter to shape the graphite and a carpenter or knife handle maker to put the graphite in a wooden case. A storekeeper named Friedrich Staedtler, who was not a member of either skilled trade, figured out how to make a better pencil from start to finish. Pencil makers became a recognized craft category by the 1730s.I was astonished to learn that Thoreau didn’t just invent a better pencil; he revolutionized the American pencil industry. American graphite was less pure than British graphite and pencils made from it smudged. Thoreau worked for a time in his father’s pencil factory and was determined to create a better product. After hitting the books at the Harvard Library, he came up with a method of blending graphite and clay that solved the problem. The Thoreau pencil factory took off. Shortly thereafter, Thoreau also took off for Walden Pond. (FYI: He went back into the pencil business occasionally when he needed cash.)That’s all I’ve got. If you’re interested in learning more about pencil history, everyone seems to agree that the book to read is The Pencil: A History of Design and Circumstance by Henry Petroski. I must admit, I’m tempted. **

*On the other hand, I’ve spent a lot of time reading about the history of paper, which was invented in China and then spread to Europe via the Islamic world—making it exactly the kind of thing I’m fascinated by.

**In fact, I’m tempted by several of Petroski’s books.

August 1, 2023

Shin-Kickers from History: Mary Heaton Vorse

In a recent blog post, I introduced you in passing to activist and journalist Mary Heaton Vorse. As is so often the case, Vorse is worth a closer look.

Born to an upper-middle class family in Amherst, Massachussets in 1874, Vorse was a prolific and high-profile novelist, labor journalist, and activist.*

In 1896, after a period of studying art in France,* she continued her studies at the Art Student’s league in New York City, which had a reputation for progressive teaching methods and radical politics. She soon discovered that she had no real talent for art and took up progressive causes, including women’s suffrage, in place of painting.

Vorse was married twice—to journalist Albert Vorse in 1898 and radical journalist Joseph O’Brien in 1912—and widowed twice. Both Vorse and O’Brien supported her writing and shared her progressive values.

Her career as an activist and journialist blossomed after O’Brien’s death in 1915.

That year she joined with a group of left-wing writers, including John Reed, Susan Glaspell, Eugene O’Neill, Theodore Dreiser and Edna St Vincent Millay, to found the Provincetown Theater Group., which was dedicated to showcase new American talent outside the rules of the commercial Broadway theater.

In the early years of the First World War, she and other progressives formed the Women’s Peace Party, with the goal of bringing the war to an end. She was one of the party’s delegates to the 1915 International Conference of Women in the Hague.

More importantly, at least in terms of the impact she made, she also turned to serious journalism. She already supported herself as a writer of short stories for women’s and general interest magazines and of romantic fiction novels, which she later dubbed “lollypops.”** Beginning in 1916, she traveled across the United States and Europe reporting on social justice issues, with an emphasis on the impact of events on woman and children that was unusual in labor journalism at the time. Her work appeared in a wide range of mainstream publications including the New York Post, Harper’s Weekly, Atlantic Monthly, New Republic, McClure’s Magazine and even McCall’s.

Her biographer Dee Garrison summed up her journalism career: “Across the space of half a century, wherever men and women battled for a wider justice, she was apt to have been there.” She reported on striking miners in Michigan and striking textile workers in New Jersey and South Carolina.She covered the Scottsboro Boys’ trial in Alabama and the battle between coal bosses and miners in Harlan County, Kentucky, where she was run out of town by thugs working for the bosses. She reported on the United Auto Worker’s strike in Flint. Michigan, in 1937 and on the steel workers’ strike in Youngstown, Ohio, where she was grazed by a bullet fired by company guards. She reported on conditions in Stalin’s Russia and Hungary under Béla Kun—experiences that led her to write in her diary “I am a communist because I don’t see anything else to be, but I am a communist who hates Communists and Communism.” In 1952, she wrote an extensive and hard-hitting investigation of dirty politicians and organized crime on the New York and New Jersey water front.

Her career as a journalist ended in 1959, at the age of 85, when she suffered a stroke on her way home from reporting on a textile workers’ strike in North Carolina.

* I am fascinated by the number of privileged children of the Gilded Age who devoted themselves to social change.

**Much like novelist Graham Greene, who dubbed his thrillers “entertainments,” as opposed to what he believed were his more serious novels dealing with issues of faith and politics. Subjects that also play an important role in his thrillers.

July 28, 2023

From the Archives: City

My editor has come through with revision notes for Sigrid Schultz and I am deep in the eternally fascinating process of seeing my book through someone else’s eyes. (And since I’ve had a couple of months away from the book, I’m also seeing things I want to revise that she hasn’t called out.) I’m making structural changes, taking stuff out, and adding stuff back in. I’m stepping back to get the big picture and focusing in at the sentence level. (In one case I have two succeeding sentences with the same, very specific format. My editor didn’t point it out, but it jumped out at me as I read. Frustrating because there is nothing inherently wrong with the sentences qua sentences and my brain is not letting them go without a struggle. I keep chanting “Kill your darlings,” but it isn’t helping.)

As a result, I am having trouble writing a new blog post. So, here’s one more from the archives:a book review that originally ran in 2012. As you can no doubt tell, I really liked the book. In fact, I just pulled it off my shelf for a little re-reading.

Cultural historian P.D. Smith argues that the city is humanity’s greatest creation. After reading City: A Guidebook for the Urban Age, it’s easy to believe it’s true.

City is not a simple chronological history of urban areas from their first appearance in ancient Mesopotamia to modern megacities. Instead, Smith organizes his work around elements of city life that “have become part of our urban genetic code”: cemeteries, street protests, slums, suburbs, markets, street food, graffiti. He draws illuminating parallels and unexpected connections. The chapter titled “Where to Stay”, for example, begins with the growth, death and rebirth of downtown, looks at immigrant neighborhoods in nineteenth century America in the context of Jewish ghettos in Europe, makes a sharp turn to slum cities in the developing world, considers the allure of garden suburbs beginning in ancient Babylon, and ends with a brief history of the hotel.

The book is punctuated by sidebars that go off at right angles to the main text. A brief history of the parking meter accompanies the section on commuting. The hanging gardens of Babylon are discussed in the context of urban parks.

Smith’s range of material is breathtaking, but he wears his erudition lightly. The prose of City is smart and fast-paced, with a nice balance between big picture history and close-up details. The book is full of “aha” moments and occasional humor. I can’t imagine a history fan who won’t find at least one section fascinating.

July 25, 2023

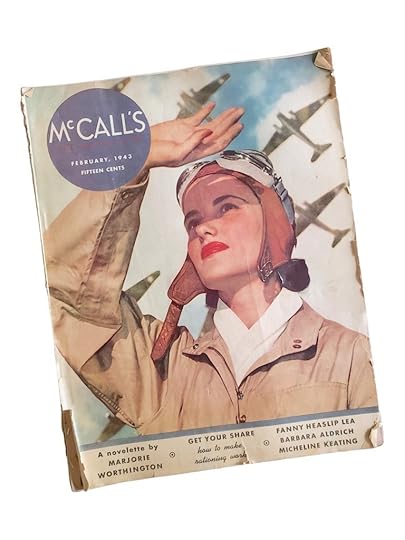

Women’s Magazines and Political Reporting

In 2016, Teen Vogue made media news with its shift from a glossy high fashion magazine aimed at teenage girls to a glossy high fashion magazine that covered feminism, social activism, identity, and politics. The change generated stories, and academic articles, with titles like “A Politics of Snap,” “Ok, Seriously,”and How Teen Vogue Got Political” I followed the coverage, which ranged from condescending to celebratory, with a certain amount of envy. Teen Vogue would have appealed to past me in a way that Seventeen, Tiger Beat, and the like did not.

Analysts discussed the long-standing division between “ladymags” (a category that stretches from Good Housekeeping to Cosmopolitan, some of which are less ladylike than others) and the much smaller category of women’s magazines with a political bent, most notably Ms. But none of them, or at least none that I saw, noted that it wasn’t the first time that women’s magazines covered the news of the day in addition to their usual subjects.

In the years between the two world wars, American women’s magazines printed articles dealing with international issues. The Delineator, the magazine published by Butterick Patterns, published a report on Russia’s battalions of women soldiers in March, 1918. McCalls* in particular had a history of commissioning well-known women reporters to write pieces on international politics. The magazine’s editor, Otis L. Weise, sent muckraking journalist Ida Tarbell to interview Mussolini in 1927 and to report on conditions in Germany in the early 1930s. At much the same time, he sent journalist, novelist and labor activist Mary Heaton Vorse* to report on the Soviet Union.

When the United States entered the war in 1941, American women’s magazines quickly looked for ways to make their content relevant for their readers in a time of national emergency. They went beyond their core subjects of fashion, homemaking, and romantic fiction to produce stories about topics such as dealing with war-time scarcity and rationing and the importance of women taking war-time jobs outside the home. McCall’s once again led the pack, hiring Sigrid Schultz to work as a war correspondent, with a view to reporting on the war from a woman’s perspective.

When the war ended, women were pushed out of their wartime jobs to make room for returning soldier. (It is only fair to remember that many of them were willing to go.) Women’s magazines responded by returning to covering their readers’ traditional interests, minus the international news. I wonder if readers missed it.

*Also published by a pattern company

**Coming soon to a blog post near you.

July 21, 2023

The Dashing Floyd Gibbons

Floyd Gibbons welcomed home in 1918.

Floyd Gibbons was one of the twentieth century’s most swashbuckling reporters, complete with a trademark eye patch, worn because he lost an eye in while advancing with the Fifth Marines on the battlefield of Belleau Wood in June 1918.

Gibbons began his career as a reporter in Minneapolis, but he gained a national reputation as a reporter for the Chicago Tribune. During the fifteen years he worked for the Tribune, he made the news as well as reporting on it. Assigned to cover General John Pershing’s troops in the Mexican Punitive Expedition in 1916,* he instead chose to travel with Mexican leader Pancho Villa, filing exclusive stories from the other side of the conflict. He was on board the liner RMS Laconia en route to London as a war correspondent when German submarine sank the ship in February 1917—and immediately filed a dramatic eyewitness report on the experience as soon as the rescued passengers reached shore in Ireland. He covered the arrival of American troops in France, the first American artillery shots fired in the war, and the first American offensive of the war at Cantigny. ** His heroics at Belleau Wood, where he lost his eye attempting to rescue a Marine officer, earned him the French Croix de Guerre and turned him into a celebrity back home: he was greeted in New York by a Marine honor guard and a crowd of shouting reporteres.

As the war drew to an end, Robert McCormick and his cousin and partner Joseph Patterson, decided to build a European presence for the Chicago Tribune and Patterson’s New York Daily News. They already had a structure in place in the form of the “Army Edition,” the newspaper McCormick produced for soldiers during the war. In November, 1918, a week after the Armistice, McCormick gave Gibbons the job of creating two overlapping news organizations that built on the Army Edition framework: the Tribune’s Foreign News Service*** and the European Edition of the Chicago Tribune and the New York Daily News, known to both its staff and readers as the “Paris Edition.”

Gibbons not only ran the Tribune’s Foreign News Service, he worked as its chief “roaming correspondent,” following stories across Europe, Asia, and Africa. He was fired in 1927, after running up a $20,000 expense account bill on a safari to Timbuktu. (He told fellow Tribune reporter George Seldes that it was worth it: he had always wanted to send his mother a card postmarked Timbuktu.)

Back in the United States, Gibbons became active in the new forms of media that were developing. He was one of the first radio news commentators, becoming known for a fast-talking style of delivery that was the verbal equivalent of his prose. He narrated newsreels, for which he received a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame, a documentary titled With Byrd at the South Pole and a series of short films called “Your True Adventures.”

Gibbons returned to foreign correspondence in the 1930s, reporting on Mussolini’s invasion of Ethiopia in 1935 and covering both sides of the Spanish Civil War in 1936.

His death on September 24, 1939, cut short his plans to return to Europe, where Germany had invaded Poland only weeks previously

*A side show in the Mexican Revolution of 1910, and not a shining hour for the United States. It probably warrants a blog post in its own right one of these days since I’ve been stumbling across it regularly for several years now. Until then, here’s a link to an old post that involves Pancho Villa’s army and the Mexican Revolution of 1910: Petra Herrera Wanted to be a General.

**Gibbons’ boss, the owner and publisher of the Chicago Tribune, Robert McCormick was also at Cantigny, where he earned the rank of Lieutenant-Colonel.

***The organization for which Sigrid Schultz worked in Berlin.

July 18, 2023

Shin-Kickers from History: Mary McLeod Bethune.

Photo credit : Carl Van Vechten. 1949 courtesy of Library of Congress

Several blog posts ago, political activist Mary McLeod Bethune (1875- 1955) stepped onto the page (okay, screen) for a moment. I realized that though I was familiar with her name, I didn’t really know anything about her. Turns out that there is a lot to know. Here are some of the highlights:

The daughter of formerly enslaved parents, Bethune was the first person in her family born into freedom and the first to receive a formal education. She went on to spend sixty years in public service, wearing many different hats but all of them in pursuit of one goal: “unalienable rights of the citizenship for Black Americans.”

After graduating from the Scotia Seminary, a boarding school established after the Civil War to educate Black girls , she attended Dwight Moody’s Institute for Home and Foreign Missions in Chicago. Unable to find a church to sponsor her as a missionary, she became an educator, teaching at schools in Georgia and South Carolina. In 1904 she opened a school in Florida, the Daytona Literary and Industrial School for Training Negro Girls. The school eventually became a women’s college and then merged with the all-male Cookman Institute to form the four-year coeducational Bethune-Cookman College in 1923. Bethune became the first Black woman in America to serve as a college president. She remained it president until 1947. The college remains once of the top historically Black colleges and universities.

While leading the college, Bethune found her way to the national political stage** through her involvement in organizations devoted to issues important to Black women in America, including voting rights. She served as an advisor to both Calvin Coolidge and Herbert Hoover. In 1935, she became the first Black woman to head a federal agency when President Franklin Roosevelt named her director of Negro Affairs of the National Youth Administration, a position she held until 1944. She established and led the Federal Council on Negro Affairs, which served as Roosevelt’s unofficial “black cabinet” on issues facing Black communities. During World War II, she was active in mobilizing Black support for the war effort and in advocating for equal opportunity in defense industries and in the armed forces—a two-pronged campaign that she summed up in a 1941 speech as “we must not fail America, and as Americans, we must not let American fail us.”

After the war, Bethune served as a consultant to the American delegation to the founding conference of the United Nations in 1945 . (In a more equal world, she would have been a member of that delegation.)

Today the Mary McLeod Bethune Council House is a national historical landmark and home to the National Archives for Black Women’s History.

July 14, 2023

From the Archives: The Nile

In Empress of the Nile, Lynn Olson referred a number of times to a book that I enjoyed in the past: Toby Wilkinson’s The Nile:A Journey Downriver Through Egypt’s Past and Present. In fact, she led me to pull it off the shelf and dip in and out.

I’m pleased to report that it’s still a good book. Here’s what I had to say about it when I first read it in 2014:

In The Nile:A Journey Downriver Through Egypt’s Past and Present, popular Egyptologist Toby Wilkinson leads the reader on a historical travelogue that moves from Aswan, home of the river’s First Cataract, to Cairo’s Gezira Island, from Paleolithic rock drawings to the Arab Spring.

In The Nile:A Journey Downriver Through Egypt’s Past and Present, popular Egyptologist Toby Wilkinson leads the reader on a historical travelogue that moves from Aswan, home of the river’s First Cataract, to Cairo’s Gezira Island, from Paleolithic rock drawings to the Arab Spring.

The voyage that shapes The Nile is not simply metaphorical. Wilkinson floats down the river on a dahabiyah–a large luxury boat descended from the royal barges of the pharaohs. Aware that he is simply the latest in the historical line of travelers drawn to Egypt by its climate and its ancient civilizations, Wilkinson engages with their commentary as well as his own observations, creating a palimpsest of Nile voyages in the process. (Ancient Greek historian Herodotus and 19th-century British journalist Amelia Edwards are particular favorites.)

Because Wilkinson organizes his work by geography rather than chronology, his narrative is anecdotal almost to the point of stream of consciousness. His combination of scholarship and storytelling allows him to draw unexpected relationships through time. The ruins at Kom Ombo lead to a discussion of the crocodile god, Sobek, then on to ancient Egyptian tales about the dangers of crocodiles, a modern Crocodile Museum, and the impact of both 19th-century Western tourism and the Aswan Dam on the crocodile population in Egypt. Occasionally such temporal leaps are disorienting, but for the most part they are illuminating. Once a reader has learned to navigate the rapids, The Nile is worth the effort.

July 11, 2023

Empress of the Nile

I am a fan of Lynne Olson’s work. I am also a lifelong archeology nerd. So when I first saw an notice about Olson’s newest book, Empress of the Nile: the Daredevil Archeaologist* Who Saved Egypt’s Ancient Temples from Destruction, it was an automatic pre-order.**

Empress of the Nile was also the first book I picked to read from the ever-growing To-Be-Read pile once I had some time to read non-fiction that was not related to the book I am working on.

I must admit, I have mixed feelings about the book. As always, Olson does an excellent job of weaving her story into its historical background, in this case, the history of Egyptology in France,*** ancient Egyptian history, the French resistance in World War II, Egyptian nationalism, and the early years of UNESCO.

At the same time, the book doesn’t entirely deliver on the story promised in the title.

The first section of the book deals with Christiane Desroches-Noblecourt’s early career as an Egyptologist. This section included her challenges as a woman in the man’s world of French archaeology, her work in the field in Egypt, her involvement in an unlikely resistance network during the German occupation of France, and her role in saving the Louvre’s art and artifacts from the Nazis during World War II. This was exactly the type of material I expected from the title and Olson had me turning pages as fast as I could go.

The second, and largest, section covers the international effort to save Egyptian monuments in Nubia, particularly the temples at Abu Simbel, from being destroyed by the construction of the Aswan High Dam. The story is interesting. Olson traces the diplomatic games required to fund the rescue project and the related infighting between various archaeological organizations and museums and describes the heroic blend of engineering and archeaology involved in relocating the monuments. But she loses track of Noblecourt for much of the story. She tells how Noblecourt kicked off the effort, refusing to simply accept that the structures must be lost. Moving forward, Olson repeatedly states that Noblecourt was a critical player in saving the structures. But she doesn’t really show the archaeologist’s involvement. Instead she focuses on Jacqueline Kennedy’s role in getting the United States to commit to the UNESCO project. Definitely interesting, and it made want to know about the former first lady.

In the final section, Olson returns to Noblecourt’s career.

Each of the sections is interesting, but the narrative structure doesn’t hold together because of Noblecourt’s repeated absence in the middle.

Bottom line, I enjoyed the book, but not as much as I expected. Dang.

*Spell check doesn’t like that extra a, but the books about archaeology that I read as a nerdy little girl who dreamed of working on digs all spelled it that way and I do, too. (And in this case, so does Random House.)

** For those of you who don’t know, publishing industry wisdom is that pre-orders are good for books and authors. Pre-orders tell publishers and retailers that people are interested in the book, in theory generating early buzz which help sells more books. If you plan on buying a book anyway, pre-ordering it from your preferred book purveyor is a way to help the author. (Does it actually work? I don’t know.) I also think of it as buying future Pamela a surprise present because I often forget I’ve ordered it. (And yes, this does mean I occasionally pre-order a book twice, thereby getting an unintended step forward on Christmas shopping.)

***A fascinating story with ties to Napoleon’s attempts to conquer Egypt.