Pamela D. Toler's Blog, page 26

September 16, 2023

From the Archives: Beyond Belief

I’ve reached a point in the revision process where I’m going back to books I read early in the research process. Because while some people may write and re-write in an absolute straight line, I do not. I move back and forth, and sometimes I zigzag. I’m definitely in a zigzag phase as I draw to the end.

One of the books I’ve gone back to is Deborah Lipstadt’s Beyond Belief, which offers an important look at “fake news” and other currently relevant topics in the context of the Holocaust. I first shared it with you in 2020. I think it’s worth another look.

I am currently taking notes on a pile of secondary source that I read over the last few months. I stuffed them full of sticky tabs as I went and moved on. On the surface, it’s not the most efficient way to do research, and I don’t always have the time to do it. But when time allows, I find it tremendously valuable. Coming back to the material a second time with a fresh eye and more information allows me to make connections that I didn’t make the first time. Re-reading is like re-writing as far as I’m concerned. It’s where the magic happens.

I just finished my second pass on Deborah Lipstadt’s Beyond Belief: the American Press and the Coming of the Holocaust, 1933-1945. The first time through it didn’t even occur to me share it with you.* And yet, and yet: it is important, not only for understanding how Americans could have remained ignorant of the Holocaust at the time, but also as a starting point for the mindset that makes today’s charges and counter-charges of “fake news” possible.

The work had its roots in the classroom. After Lipstadt told her class that detailed information about the Nazi attempt to exterminate European Jews had been available to the Allies very early in the war, one of her students angrily responded “But what did the public—not just the people in high places—know? How much of this information reached them? Could my parents, who read the paper every day, have known?”

Lipstadt argued that a great deal of information was available. American reporters who were stationed in Germany until the United States entered the war had reported on the Nazis in detail, including information about Germany’s persecution of the Jews.

The student wasn’t convinced. “No,” he said. “I can’t believe people could have read about all this in their daily papers.”

Beyond Belief began as Lipstadt’s attempt to prove that she was right. Her final conclusion, which she offers to the student in her acknowledgements: “I was right, but so were you.”

The book consists of a detailed look at who reported what and when, what their editors did with it after they reported it,** and how readers responded. Some of the most powerful portions of the book, and the ones that I think are most important for us today, discuss what Lipstadt describes as “the barriers to belief.” The most critical of these was a legacy from World War I. Stories of German atrocities were reported in the first World War that later proved to be false. The result was an attitude of what journalist and historian William Shirer called “supercynicism and superskepticism” about reports of atrocities. As a group, Americans said “Fool me once, shame on you. Fool me twice, shame on me.” unfortunately, this time the stories were true.

Be warned, Beyond Belief is not an easy read. Lipstadt’s style is clear, but her work is dense with data. Nonetheless, I found it a worthwhile read for reasons well beyond my current research.

*I don’t normally discuss purely academic works of history here in the Margins. They have a different purpose and a different audience and occasionally just plain hard to read.

**Important stories often got buried deep in newspapers. Editors (and sometimes reporters) added seeds of doubt to the reported stories. And some papers didn’t run the stories at all.

September 12, 2023

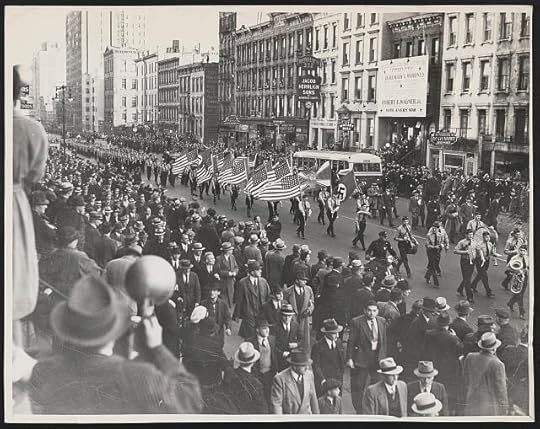

American Nazis

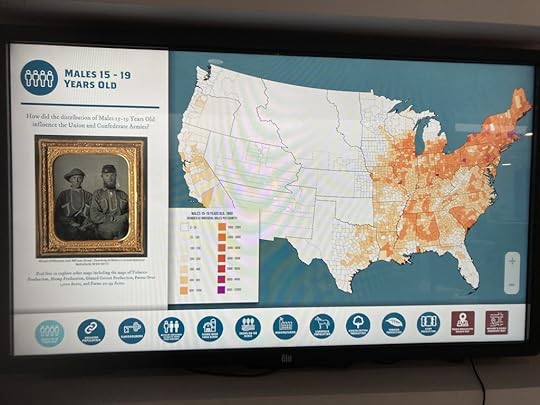

German American Bund Parade, October 30, 1937

In response to a request from a blog reader,* who mentioned that she would like to know more about Americans who supported the Nazis, I’m going to give it a go.

In the early years of Nazi Germany, American students and tourists came back with glowing reports on Germany, and raised questions about the accuracy of serious reports of problems in the Nazi state written by journalists like Sigrid Schultz. (Because a casual observer always knows more than an expert.) Antisemitism was widespread in American culture. Isolationism was a serious political position, espoused by groups like the America First Committee. (Charles Lindbergh was the most prominent figure in all of this.**) It’s an ugly picture, and all too easy to forget in the context of the powerful national narrative of World War II, but as best I can tell, most of these people were not active Nazi supporters. (Though Lindbergh seemed to tiptoe in that direction.

However, there were several organizations in the United States in the years before the war that actively supported Hitler and the rise of fascism in Europe. The most prominent of these was the German-American Bund, which was based in Manhattan and had seventy chapters with thousands of members across the United States. The Bund was founded in 1936 by a German immigrant named Fritz Kuhn, who was a veteran of World War I (on the German side) and became an American citizen in 1934. The Bund was explicitly for German-Americans and their Austrian cousins. It combined Nazi ideology, with its toxic mix of “Aryan” cultural and racial superiority, “scientific” racism, and antisemitism, and what its members framed as American patriotism.

At its height, the Bund sponsored parades, concerts, bookstore and youth camps, which introduced German-American children to camping skills and Nazi ideology. Like their German counterparts, the Bund also had uniformed storm troopers. Not a typical element in American social clubs.

The House Committee on Un-American Activities (HUAC), best known for their Cold War investigations of suspected communist sympathizers, was formed in 1938 to investigate the German-American Bund and other pro-Nazi organizations and sympathizers. HUAC reached the conclusion that while the German-American Bund was overtly racist, its activities were protected by the First Amendment. The FBI, which also investigated the Bund, concluded that it was not a threat to American security. (In all fairness, Nazi rhetoric at that point was horrifying but was not directed at the United States. That came later.)

The high point (or maybe the low point) of Bund activities was a rally at Madison Square Gardens on February 20, 1939. Kuhn called it a “mass demonstration for true Americanization.” Twenty-two thousand members attended. They carried banners with antisemitic messages taken straight from the Nazi handbook:** “Wake up America! Smash Jewish Communism!” “Stop Jewish Domination of Christian Americans.” They gave the Nazi salute to three-story tall banners depicting George Washington, flanked by swastikas.

One hundred thousand anti-Nazi protestors, also carrying banners, surrounded Madison Square Gardens. A few protestors managed to get into the rally. A Jewish plumber named Isadore Greenbaum made his way onto the stage and interrupted Fritz Kuhn’s address, screaming “Down with Hitler.” Bund storm troopers beat him right on the stage until the police intervened and got him to safety. The storm troopers were more gentle with celebrity journalist Dorothy Thompson,*** who shouted “bunk” from the audience. They surrounded her and escorted her from the building.

Within a year, the organization had crumbled. Kuhn was convicted of forgery and embezzlement and other leaders of the Bund was interned as a dangerous alien. By the end of December 1941, following the attack on Pearl Harbor and Germany’s declaration of war against the United States, the government outlawed the Bund.

* I LOVE it when you guys suggest blog topics. Sometimes I actually know stuff about the question. Sometimes I have to rabbit-hole it. Either way, I’m a happy history nerd. Today’s post is a combination.

**The more I read about him, the less respect I have for the man.

***Not a literal Nazi handbook. Though Germany did create a horrifying handbook for its athletes at the time of the 1936 Berlin Olympics.

***You didn’t think I was going to get through this without mentioning a woman journalist did you?

###

If you want to know more about American Nazis in the years before World War II, I strongly recommend Arnie Bernstein’s Swastika Nation.

September 9, 2023

A War by Any Other Name

British howitzer camouflaged in France during the “phoney war”

World War II ended, literally, with a bang. In some ways it began with a whimper. First Germany and then the Soviet Union invaded Poland in September 1939* After Warsaw officially surrendered to Germany on September 28, active hostilities slowed on the Western front. Germany consolidated its hold on Poland. Britain and France built up their forces, took defensive positions along the Franco-Belgian border,—and waited. Hostilities resumed again in April, 1940, when Germany invaded Norway.

I’ve always known this period of relative inactive as the “phoney war”—a term attributed to isolationist Senator William E Borah of Idaho, who stated on September 30, 1939, that “there is something phony about this war.”** I was surprised to learn that several alternative nicknames were popular at the time: the British “Bore War”, the German “Sitzkrieg” (or sitting war), and, my personal favorite, Winston Churchill’s poetic “Twilight War.”

Who knew?

*I don’t know about you, but my World History class left out, or perhaps minimized, the fact that the Soviet Union also invaded Poland. In fact, the German-Soviet non-aggression pact that was signed in August 1939 provided for more than non-aggression. It included secret protocols that partitioned Poland between Germany and Russia. Again.

**Borah is best known for the things he led the charge against: the Versailles Treaty (which the United States did not sign), the League of Nations (which the United States did not join), and giving women the right to vote .

September 5, 2023

History on Display: Wilson’s Creek National Battlefield

I recently took a short, (relatively) spontaneous trip home to the Missouri Ozarks. While I was there, my parents and I visited the nearby Wilson’s Creek National Battlefield, site of the first major Civil War battle fought west of the Mississippi on August 10, 1861.*

Wilson’s Creek became part of the National Park System in 1961, on the hundredth anniversary of the battle and a month after my third birthday. You could say that the park and I grew up alongside each other. It certainly was part of my education as a little history nerd.

Every time I’ve returned to the part as an adult, the exhibits have been more sophisticated and more nuanced. (I’d like to think the same could be said about me.) This visit did not disappoint.

The main change to the exhibit was a new emphasis on slavery in southwest Missouri in the years before the Civil War (some of which was new to me**), the participation of Black and Native American soldiers in the war, and the role Missouri played in the events leading up to the war. Here are some of the things that caught my attention on this visit:

An excellent video showing how nineteen century armies maneuvered field artillery, with a digression into the number of horses used and killed in the war. (I was reminded of our visit to a museum dedicated to the engagement known as the Falaise Pocket in Normandy in World War II where we were told that it was two years before people could plant crops agains because the ground water was so polluted with the corpses of men and horses. I’ve said it before, and I’ll say it again: war is ugly.)An important component of the soldiers who fought for the Union at Wilson’s Creek were Germans from Saint Louis who had immigrated to the United States after the revolutions that swept Europe in 1848. The ’48ers had come here in search of freedom and were violently opposed to slavery. I had learned about this on my last visit to the battlefield, but it hit me harder this time, perhaps because I’ve spent the last few years deep in Nazis and American Nazi-supporters.With a few colorful exceptions, like the various Zouve units, we think of the armies dressed in uniforms that were, well uniform: blue for the Unions and gray for the Confederacy. In fact, many men fought at Wilson’s Creek in the same clothes they wore as civilians, making it hard to tell friend from foe on the battlefield. Even more confusing, at least one existing Union unit had gray uniforms.A interactive map that displayed demographic and economic data about the United States in 1861 down to the county level. I am a sucker for historical maps—after all, history occurs in both time and space. This one was absolutely fascinating. Some of the topics were expected: where cotton was grown for instance. Others were surprising: the distribution of what the map maker calls the “equine population”. (This did make me wonder how they got the information. ) I could have spent a lot more time with that map, and may on future visits.In short, a worthwhile stop if you are in the area. I love the fact that the National Park Service is beginning to address the parts of history that most of us weren’t taught in school. Plus, maps.

*For those of you who don’t carry a timeline of the American Civil War in your heads: The war began with the fall of Fort Sumter on April 12 1861. The first full-scale battle of the war, variously known as the First Battle of Bull Run or the First Battle of Manassas—depending on whether you are reporting events from the Union or Confederate perspective—occurred on July 21, 1861. In other words, the Battle of Wilson’s Creek was early in the war. If you want details about the battle itself, I recommend you check out the park website. As always, the National Park Service does an excellent job of telling the story.

**I was surprised to learn that the vast majority of slaves were in the area surrounding St. Louis and moving south. This upended many of my assumptions.

September 2, 2023

From the Archives– Shin-Kickers From History: Samuel Gompers and the American Federation of Labor

It’s the Labor Day weekend here in the United States. A holiday that many of us celebrate by firing up the grills, hitting up sales, and attending outdoor festivals. In short it is a day off. Something we can thank the American labor movement for, along with child labor laws, the forty-hour week, paid vacations, etc. (1)

One of the major players in the early labor movement in the United States was Samuel Gompers.

Gompers (1850-1924) was born in East London. His family immigrated to America when he was thirteen and settled in the Jewish community on Manhattan’s Lower East Side. For eighteen months, Gompers and his father rolled cigars in their small apartment before finding better job in cigar workshops.

In the evenings, Gompers attended free lectures and classes at Cooper Union. He received an education on the floor of the cigar workshop as well. Unlike many other skilled trades, cigar rolling was quiet work and talking was allowed. Sometimes one of the men in the shop would read to the others.

Gompers and his father soon joined a branch of the United Cigar Makers’ Union. Gompers was not very active in union business until the early 1870s, when the position of skilled cigar makers was threatened by the proposed introduction of a cigar mold that simplified an important step in the cigar-making process. He joined other union members in a series of strikes protesting the use of the mold, with its threat of making skilled workers less necessary.

During this period, Gompers also attended socialist meetings and demonstrations. He was drawn to Marx’s critique of capitalism, but came to the conclusion that socialist goals of long-term transformation were in conflict with the desire of most workers for immediate change. He described his own labor philosophy as “bread and butter unionism.”

After the failure of a 107-day strike, Gompers and fellow union member Adolph Strasser decided to reorganize the Cigar Makers’ Union. The new Cigar Makers’ International Union charged relatively high dues, which allowed them to build a strike fund and offer a benefits program. The idea was to build a sense of identity among union members based on their shared skills and bind them to the union through an extensive benefit system.

In 1881, Gompers was instrumental in creating another level of union strength in the form of a national federation of trade unions, the Federation of Organized Trade and Labor Unions, which became the American Federation of Labor (AFL) in 1886. By 1900, the AFL had roughly 1 million members. (2)

(1) Benefits that not all Americans enjoy even today.

(2) This post is drawn from a chapter on socialism in America from my first book for adults: The Everyday Guide to Understanding Socialism.

August 30, 2023

In which I share a small Nazi story

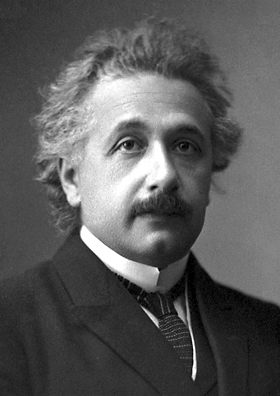

In an article dated March 21, 1933, Sigrid Schultz reported that the Nazis had raided a country home in search of weapons.* The events was a small incident in the larger Nazi program against German Jews. It would probably not have made the news if the home had not belonged to Albert Einstein, who had won the Nobel Prize in 1921 and was always good news copy.

Albert Einstein’s official Nobel Prize portrait, 1921

The Nazis claimed they had received information that large amounts of arms and ammunition was cached in the scientist’s home. In fact, Schultz told her readers, “the nearest thing they found to arms was a bread knife.”

It is not clear what the Nazis hoped to accomplish. Einstein, who had denounced the Nazis and predicted a Fascist reign of terror as early is 1931, was then on his way to the United States. Before his departure, he had announced that he would not return to Germany under Hitler’s rule.

Not a story that matters in the the bigger picture except for two unrelated sentences buried in the middle of the article: “Authorities have announced that the first concentration camp for communists will be opened Wednesday at Dachau, near Munich. It will accommodate 5,000 Reds now in jail, as well as other political prisoners.”—one of the earliest references to the concentration camps, in an American paper

*For those of you who don’t have a timeline of Nazi Germany in your heads, Adolf Hitler was sworn in as Chancellor on January 1, 1933. On March 23, the Nazis pushed a set of bills called the Enabling Acts through the Reichstag. These acts gave Hitler the ability to rule by decree and made control of the Reichstag irrelevant.

August 26, 2023

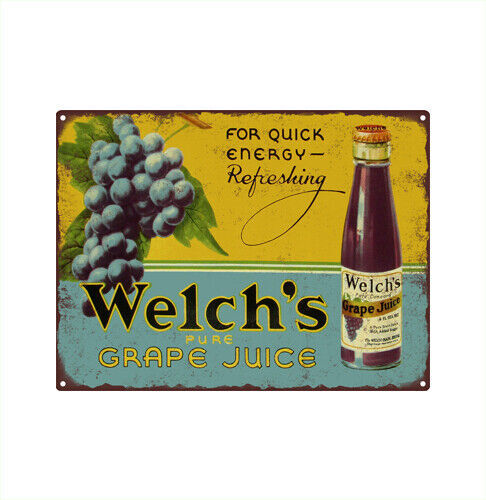

In which I talk about the revision process and Welchs’ Grape Juice

As I work on these revisions,* I am dipping back into Sigrid Schultz’s documents, including the daily logs that she kept on and off over the years, looking for details that I remember but can’t quite put my hands on.*** In the process, things catch my attention that didn’t strike me the first, or fourth, time around.

As I work on these revisions,* I am dipping back into Sigrid Schultz’s documents, including the daily logs that she kept on and off over the years, looking for details that I remember but can’t quite put my hands on.*** In the process, things catch my attention that didn’t strike me the first, or fourth, time around.

For example, in her notes about a trip to the United States in 1933, Schultz noted “drink grape juice Welch.” It was hard for me to imagine why Schultz, who spent considerable time choosing wine for her personal cellar and occasionally splurged on a small keg of whiskey straight from the distiller, would think a swig of grape juice was worth noting. (She didn’t note whether she liked it. I know she was a big fan of orange juice.****)

As those of you who have been following along can guess, I went straight down the rabbit hole.

Turns out that, like the first Kellogg’s cereal, Welch’s grape juice was an innovative product developed to lead Americans to a more virtuous life. Who knew?

In the case of Welch’s grape fruit juice, the target was alcohol. As the American temperance movement grew, some churches became concerned about the use of sacramental wine in communion services. The obvious solution was to substitute grape juice for wine, but it wasn’t as easy as it sounds. Grape juice stored at room temperature naturally ferments and fresh grapes are not available year round in many parts of the United States.

In 1869, aa Methodist dentist named Thomas Bramwell Welch pioneered the process of pasteurizing grape juice as a way of stopping the fermentation process. According to some versions of the story, he started experimenting with the process when a member of his congregation appeared at his house tipsy from too much communion wine—it’s a fun story, but I find it unlikely unless his guest was swigging communion wine direct from the bottle.

Welch made batches of what he called “Dr. Welch’s Unfermented Wine.” in his kitchen with grapes picked from a trellis just outside the door. He then attempted to sell it to churches as a substitute to wine for communion. The product wasn’t an immediate success. It only took off after Welch’s son changed the name to Dr. Welch’s Grape Juice, widened the proposed audience, and served it at the 1893 World’s Fair. The popularity of the product grew alongside the temperance movement.

In 1933, when Sigrid Schultz gave it a try, Prohibition was coming to an end. The beverage she tried while she was in New York was a Manhattan.

*Which feel endless, I tell you, ENDLESS! To quote novelist Jami Attenberg** on the subject: “It’s just steady fucking work, and I have no choice but to hammer through it and it’s not always interesting, even if the book itself is always interesting. Let’s put it this way: solving the problem is fun, implementing the solution is (often) not.”

**If you are interested in the writing process or creativity in general, and can tolerate regular f-bombs, I strongly recommend Attemberg’s weekly newsletter. https://1000wordsofsummer.substack.com/ She is always smart and consistently inspiring.

***I make extensive notes as I research, typing anything that I think might be useful into a chronological Scrivener document that I grandly call the research draft. (It is not a draft in any meaningful sense. In the case of this book, it is a 500,000+ word mass of stuff from which I can build the first really messy draft.) In theory, I should be able to use the search function to find anything I need. In reality, that I assumes I 1)remember a useful key word to use as a search term and 2) thought the item in question had a chance of being useful.

****These are the kinds of details a biographer learns without even looking for them.

August 22, 2023

From the Archives: Clara Barton, Act III–the American Red Cross

For the next little while, I’m juggling revisions with prepping for a talk about Civil War nurses. (I love giving talks, but I was overly optimistic when I agreed to do this one last September.) It makes for an interesting mix of tough broads competing for my attention.

Working on the theory that if I’m thinking about Civil War nurses, you should be too, I offer you a three part series from back in 2016. If you’re coming in late to the story, you can read part one and two here and here.

Clara Barton in 1904

When we last saw Miss Barton, she was in Switzerland, recovering from the exhaustion of her war efforts. She didn’t rest for long. When the Franco-Prussian War broke out in 1870, Barton leapt back into action. Constrained by her lack of political connections in Europe, she did not try to work on her own the way she had in the American Civil War. Instead she traveled to Strasbourg as a volunteer of the International Red Cross, wearing a cross she improvised from a red ribbon and a Red Cross pin given her by the Grand Duchess Louise, daughter of Kaiser Wilhelm I.

The International Red Cross had been founded several years before. In 1863, while the United States was locked in its internal struggle, Swiss businessman Henry Dunant, who had witnessed the aftermath of the Battle of Solfierno in the Italian War of Independence several years before, called a conference of thirty-nine delegates from sixteen nations to Geneva to discuss questions of battlefield relief and humanitarian aid. The group met again in 1864 and created the set of recommendations that would become the Geneva Treaty, now the Geneva Convention. The guidelines called for the humane treatment of wounded soldiers and universal recognition of the neutrality of medical personnel, ambulances, and hospitals in time of war. The convention adopted a reverse Swiss flag, a red cross on a white ground, as an emblem of medical neutrality that would be easily recognized. They also urged each country to create its own national society of volunteers to provide battlefield relief when needed. Twelve European governments ratified the treaty. The United States refused to sign on the grounds that it was a possible “entangling alliance.”*

Barton’s experience in the Franco-Prussian War was very different from her experience in the American Civil War. Instead of caring for wounded soldiers, she worked with the war’s civilian victims. For her first several days in Strasbourg, she dutifully served soup and distributed supplies to survivors. But as she spent more time in the burned-out city, she realized that more than soup and soap were needed. She organized women into sewing workrooms as a first step in reestablishing the city’s economy. She organized a similar relief effort in Paris the following year.

When she returned home in 1873, Barton took on the task of lobbying for the United States to ratify the Geneva Treaty. It took her nine years and three presidents to convince the government. President Chester Arthur signed the treaty in 1882, and the Senate ratified it several days later.

Barton founded the American Red Cross in 1881 and led it for the next twenty-three years. At her initiative, the American Red Cross proposed an amendment to the Geneva Treaty calling for the expansion of Red Cross relief to include victims of natural disasters. The so-called American Amendment, perhaps more accurately the “Barton Amendment,” was passed in 1884.

Under Barton’s leadership, the American Red Cross helped victims of the Johnstown flood,** hurricane victims in the Sea Islands of South Carolina, both Armenian and Turkish victims of ethnic unrest in the Ottoman empire,***and famine victims in Russia. (If you can’t be described as a victim or something, you probably don’t need the Red Cross.) She traveled with nurses to Cuba during the Spanish-American War in 1898 to nurse the wounded and provide supplies. Her last relief operation with the Red Cross was distributing supplies and financial assistance to survivors of the hurricane that wiped out Galveston, Texas, in 1900.

After she retired from the American Red Cross in 1904 at the age of 82, she founded an organization to teach basic first aid and emergency preparedness, wrote several books, and went on a speaking tours.**** She died at home on April 12, 1912 at the age of 90.

A life well-lived by any standard.

If you’re interested in learning more about Clara Barton– including the slightly scandalous bits that I didn’t have room for in either these blog posts or Heroines of Mercy Street–I strongly recommend Stephen Oate’s excellent biography, A Woman of Valor: Clara Barton and the Civil War.

*The same reason we failed to join the League of Nations after World War I.

**The 68 year old Barton personally led fifty volunteers on the first train into town following the disaster

***In 1896, well before the Armenian genocide of 1915. Obviously a long-standing conflict.

****Do you feel like a slacker yet?

August 19, 2023

From the Archives: Clara Barton, Act 2–Finding the Missing

For the next little while, I’m juggling revisions with prepping for a talk about Civil War nurses. (I love giving talks, but I was overly optimistic when I agreed to do this one last September.) It makes for an interesting mix of tough broads competing for my attention.

Working on the theory that if I’m thinking about Civil War nurses, you should be too, I offer you a three part series from back in 2016. If you’re coming in late to the story, you can read part one here.

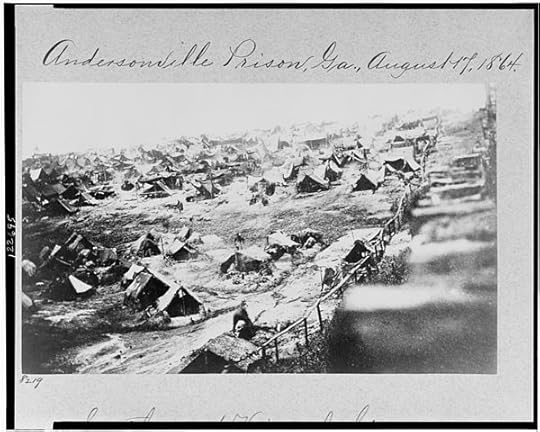

Clara Barton helped identify graves at Andersonville Prison

When the Civil War ended, most of the women who had volunteered to serve as nurses went home and stepped back into their old roles as daughters, seamstresses, schoolteachers, and wives. (Not to mention factory workers, New York socialites, reformers…) Nursing had been a temporary event in their lives, just like being a soldier was a temporary part of the lives of most of the men who served in the war.

Clara Barton was one of the exceptions. (Does this come as a surprise to anyone?)

After the end of the war, women wrote to Barton asking her to help them find missing husbands and sons, whom they feared had ended up in Southern prisons. The anguish in their letters convinced her that locating missing soldiers was the most important thing she could do now that peace had come. Barton opened the Office of Correspondence with Friends of the Missing Men of the United States Army, which operated out of her own rooms in Washington. She put together lists of missing soldiers, organized by location and unit, posted them in army hospitals, and had them printed in local and national newspapers, with the request that any information about the missing men be sent to her to pass on to their families.

Eventually she received official sanction for her new mission. Shortly before his assassination, President Lincoln wrote a letter to the public informing them to contact Barton with information about missing soldiers. When her own resources were exhausted, Congress appropriated $15,000 to complete the project—close to $3 million today. The search for missing soldiers led to an effort to identify graves, beginning with the unmarked graves of the 13,000 Union soldiers who died in the prison camp at Andersonville, Georgia. Between 1865 and 1869, she and her assistants received and answered more than 63,000 letters and helped locate 22,000 missing soldiers.

Her grueling work in the war had left Barton physically exhausted; her efforts after the war imposed a new kind of strain. In 1869, she was near collapse. Her doctors ordered her to Europe for a rest cure.** She did not rest for long. While in Switzerland she became aware of a little organization called the International Red Cross. Perhaps you’ve heard of it?

*A standard medical prescription for exhausted Americans** in the nineteenth century, which has sadly fallen out of favor. Personally, I think taking a rest cure soon would be a fine idea.

**At least for those with the time and money to spare. My guess is that no one suggested an exhausted small farmer or factory girl take several months in Switzerland.

August 16, 2023

From the Archives: Clara Barton–Nursing Outside the Box

For the next little while, I’m juggling revisions with prepping for a talk about Civil War nurses. (I love giving talks, but I was overly optimistic when I agreed to do this one last September.) It makes for an interesting mix of tough broads competing for my attention. It is possible that punches will be thrown before it’s over. (Sigrid Schultz learned to box when she was a child.)

Working on the theory that if I’m thinking about Civil War nurses, you should be too, I offer you a three part series from back in 2016 to amuse you while I try to keep the ladies under control

Clara Barton, ca. 1866

When I first began talking to Little Brown and PBS about writing Heroines of Mercy Street, most of what I knew about nurses in the American Civil War could be summed up in two words: Clara Barton.*

Barton first caught my imagination when I was seven or eight, thanks to a child’s biography that belonged to my mother. ** Coming back to her as an adult, I found that her story was more complex, and more amazing that I had realized. Instead of being the archetypical Civil War nurse, Barton was an original who worked outside the system. She avoided any alliance with the official nurses, though she did not hesitate to alternately charm and kick men in high places to get the support and permission she needed in order to provide comfort and medical care to “her boys” on the battlefield.

When the Civil War began in April, 1861, Barton was working as a clerk at the United States Patent Office , one of only four women employed by the federal government before the war. (In short, she was already a shin-kicker.) After Bull Run, she visited the wounded in the improvised hospital on the top floor of the Patent Office every day, bringing them delicacies and helping where she could.

Barton soon became a one-woman relief agency. She developed a personal supply network of “dear sisters” who sent her packages of food, clothing, wine, and bandages to distribute to the troops. In fact, she received so many boxes that she had to rent warehouses to store them.

Over time she became convinced that she was needed on the battlefield, where she could help men as they fell. When the Army of the Potomac was mobilized in the summer of 1862, Barton convinced the head of the Quartermaster Corps depot in Washington to assign her a wagon and a driver.

Armed with a pass signed by Surgeon General Hammond that gave her “permission to go upon the sick transports in any direction for the purpose of distributing comforts to the sick and wounded, and nursing them, always subject to the direction of the Surgeon in charge,” Barton delivered her supplies to the field hospital at Falmouth Station, near Fredericksburg. But she still felt she was not doing enough. When she heard that fighting had broken out at Cedar Mountain, she headed for the battlefield. Thereafter, in battle after battle, Barton ran soup kitchens, provided supplies, nursed the wounded, and tried to keep track of the men who died so she could tell their families what had happened to them. In between battles, she returned to Washington, where she collected the latest batch of supplies, wrote impassioned letters thanking the women who provided them, and fought with bureaucrats to be allowed to continue her work.

She became a such a familiar figure of comfort to wounded men, that scores of the men she helped on the battlefields named their daughters “Clara Barton” in her honor. But that wasn’t her only legacy after the war…

[This is known in the trade as a cliffhanger. Don’t touch that dial.]

*Okay, six words: Clara Barton and Louisa May Alcott.

** I know I’ve mentioned them before, but I owe a debt of gratitude to the authors who wrote biographies for young girls about smart and/or tough women who sidestepped (or kicked their way through) society’s boundaries and accomplished stuff no one thought they could accomplish. (Now that I think of it, a lot of those biographies were set in and around the American Civil War–which like WWI and WWII opened doors to women that had previously been closed.) To those of you writing similar biographies today, you’re making a difference. Thank you.