Pamela D. Toler's Blog, page 28

July 4, 2023

Happy Fourth of July

Here in the United States, we are celebrating the Fourth of July: one of those holidays where the point is often lost in the trappings.

Take a moment in your celebrations to remember what we’re celebrating:

“We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.”

As a society, we’ve never managed to live up to it. That doesn’t mean we shouldn’t try.

June 30, 2023

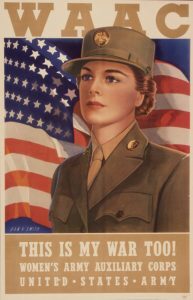

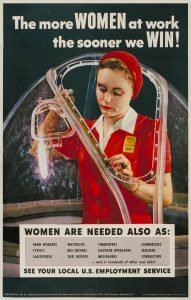

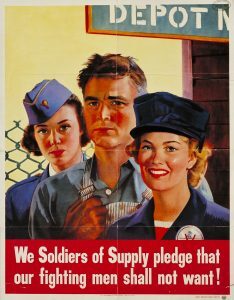

Uncle Sam Wants You, Too–Pt 2

Sayde R. Carter working a lathe at the Sperry Gyroscope plant on Long Island, New York. Hagley Museum and Library.

After my last blog post, about how women were recruited for war work during World War II, a dear friend and regular reader asked me whether similar ads were run in publications read by minorities. It’s a good question, and one I’m slightly ashamed that I didn’t ask. Certainly the women in the recruiting posters that I found all had white faces.*

I don’t have a solid answer, but here’s what I found in a first pass:**

I found nothing about ads in magazines aimed at Black women, though such magazines existed. I found references to ads for women in the Army in black newspapers. Applications were available in all post offices, but Black women were often turned away when they tried to apply. Even when Black women were given applications, the number accepted was small. The Women’s Army Auxiliary Corps (WAAC) , later the Women’s Army Corps (WAC), had a policy limiting the number of Black women to ten percent of the whole. Those who were allowed to enlist were often given menial jobs regardless of their qualifications. Initially no Black units were assigned overseas. The one exception to this was 6888th Central Postal Directory Battalion, which was sent first to England and then to France to deal with a huge backlog of mail.The other U.S. military services did not accept any Black women initially, and never accepted many.Black women (and men) were initially turned away from factory jobs by managers who preferred to hire white men, and failing that white women. In the summer 1941, President Roosevelt became aware of the widespread hiring discrimination thanks to activists Mary McLeod Bethune and A. Phillip Randolph. He signed an executive order banning racial discrimination. Ultimately, more than half a million “Black Rosies” worked in shipyards and factories, though my guess is that they continued to face discrimination on the job.If the National Archives excellent blog, The Unwritten Record,*** is to be believed, I didn’t find images of Black women in war work recruiting posters because they weren’t included in war materials produced by the Office of War Information—erasing them from the story even as it happened. ****None of which answers the original question, which would require some nitty gritty academic work in original sources.

If any of you have something to add to the story, I would love to hear it.

* Asking “Who’s not in the picture?” is as important as “Who’s telling the story?” The learning curve continues. Please, please, ask me the hard questions when I fail to ask them myself.

**I limited my search specifically to Black women, rather than looking for minorities as a whole.

***The Unwritten Record is produced by the Special Media Records Division of the National Archive. I learn something new with every post.

****Again, for those sitting in the back: “Who’s telling the story?” is a good question to ask.

June 27, 2023

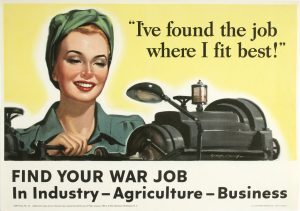

Uncle Sam Wants You, Too

As I’ve mentioned before, in the course of working on Sigrid Schultz’s life, I’ve made an effort to track down women whose names appear in her correspondence.* I’ve found some interesting stories in the process.

I was scanning the Chicago Tribune looking for information on a woman named Ann (or Anne) Bruyere, who was reportedly filing stories from the front for the Tribune,** when I saw a boxed notice in the middle of a list of casualties in the February 4, 1945 paper. It read:

ARMY NEEDS WOMEN Lengthening lists of wounded have intensified the army’s immediate need of women to learn to be medical technicians, the army recruiting station here has announced. Women desiring information on the army’s medical technician program were urged to call Harrision 4390

I knew women had served in many capacities in the war, in and out of the military. But I had never thought about efforts to actively recruit women for jobs outside of the military.*** But of course, Rosie the Riveter didn’t just show up at the factory door and ask for work, did she?

In fact, that small ad in the Tribune was part of a major campaign coordinated through the Office of War Information to recruit women into the wartime labor force. Posters urged women to find their war jobs. Government flyers explained the types of jobs that were available and told women how to register for them In particular, magazines aimed at women encouraged women to enter male fields that were short of workers, directly in advertisements**** and indirectly in fiction with working women as heroines. The choice of the verb “recruit” was deliberate: women’s war work was portrayed as national service—and rightly so.

* I plan to discuss the why and the therefore what of this tactic in my newsletter in coming weeks. If this sounds like the kind of thing you’re interested in, you can subscribed here: http://eepurl.com/dIft-b

**Stay tuned for more on Anne Bruyere and other lesser known women reporters in later posts.

***And yes, I realize this ad is for an army program, but it seems to be for a program other than the Women’s Army Corps (WAC).

**** Ads for jobs ran alongside ads run by corporations to encourage women to join the war effort. For example, an ad run Eureka vacuum cleaners proclaimed “You’re a Good Soldier, Mrs. America.”

June 20, 2023

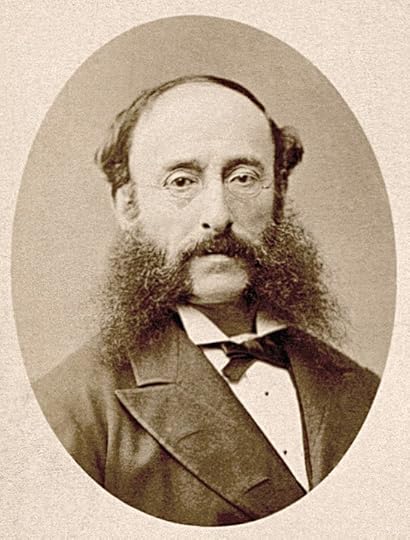

Wire Services and Carrier Pigeons

Over the last few years, I’ve spent time learning about the larger history of journalism in order to understand Sigrid Schultz in context.

The growth of the wire services was an important part of that story. The services were predecessors to the foreign news bureaus that developed after World War I and then their competitors.

As the name implies, the wire services were founded in the mid-nineteenth century in response to the development of the telegraph (i.e. the wire). But I was surprised to learn that that one of the earliest series, Reuters, began as a “bird service” rather than a wire service.

In 1848, when Europe was torn by revolutions, German-born Paul Julius Reuter worked in a Paris-based news agency, where he translated extracted from French publications to send to papers in Germany. He noticed an opportunity in the form of a gap in telegraph service between Brussels and Aachen, the terminal points between the French-Belgian and German telegraph lines. News traveled between the two cities by mail train. Anyone who could find a faster way to send financial news would have a serious advantage. Reuters left Paris and set up his own news agency in Aachen, using carrier pigeons to fill the gap and send information from the Paris stock exchange to Berlin.

The advantage only lasted until the telegraph connected the two cities a year later, but it was long enough to establish Reuter as a player in the news agency game. When the new Dover-Calais line opened in 1851, he relocated to London, where his company grew into one of the great European news services.

June 16, 2023

Constance Harvey Indulges in a Bit of Monkey Business

Constance Ray Harvey was an American Foreign Service Officer at the beginning of World War II—one of the first women to hold that position.* She was assigned to the U.S. Consulate in Lyon, in Vichy France, in January 1941. Once there, she used her position as Vice Consul to gather information and smuggle it out of France to the United States to General Barnwell Legge, the U.S. military attaché who ran a successful information network out of Bern, Switzerland.

Harvey’s personal contacts in occupied France gave her access to information about the war. Her role as Vice Consul gave her access to diplomatic correspondence pouches. The pouch traveled from Lyon to Bern, and then across Spain and Portugal to Washington, with a stop in General Legge’s office in Bern. Harvey was the last person to handle the bag in Bern, so she was able to add information without fear of another consular employee knowing what she was forwarding to Legge.

More than once, she delivered the diplomatic pouch to Legge herself, driving from Lyon to Switzerland—a trip that required her to deal with Vichy French and German Gestapo officers at the border. One of the most important, and dangerous, documents she carried personally was a plan that showed all the German anti-aircraft posts around Paris. She later remembered that when she handed it to Legge, he went white and said “Oh, for goodness sake, you just brought this in by hand?” She had used one of her favorite tricks to get it through—a variation on the magician’s principle of misdirection. Her car’s glove box had a separate key—an unusual feature. She would lock the documents in the glove box and tuck the key into the bosom of her dress. When she got out of the car to talk to the customs’ officials, she would leave the car keys dangling in the ignition—nothing up her sleeves!

In addition to smuggling information to Legge, she was part of a network that helped prominent Belgians escape, some of whom carried counterfeit Belgian passports signed by C.R. Harvey.

In November, 1942,—almost a year after the United States entered the war* and two years after Harvey began her intelligence collecting activities—Constance Harvey and the other employees of the American consulate in Lyon were interned by the Vichy government. They were housed in h hotels in Lourdes until the Germans took them into custody and relocated them to Baden-Baden, where they were held until February, 1944.

Harvey received the Medal of Freedom in 1947 for her service to the French underground. Talking about her experiences later, she minimized the importance of her role: “Quite a few people were [given the Medal of Freedom] who had been up to some monkey business—just to help out.”

*Her first post was in Italy in 1931. From there she was transferred to Switzerland after the Munich Conference in 1939.

*I will never be able to type that phrase again without hearing Sigrid Schultz saying indignantly “Germany declared war on us first!”

June 13, 2023

In Memory of Jack French

A reader informed me last week that long time reader and occasional contributor of guest posts Jack French recently died after a short illness.

One of the best parts of writing this blog is getting acquainted with readers. You send me emails commenting on posts, pointing out typos,* recommending books, and sharing ideas. We end up in conversation over time. Sometimes I even get to meet you in real life.

Jack French took things one step further. He didn’t just share stories and links to interesting stuff. He wrote occasional guest posts on topics that were very much on point for the blog.

Here are links to his posts over the last few years:

The Lady Who Invented Monopoly

In Which a History in the Margin’s Reader Recommends a Book

Two WASP Pilots Show the Men How It’s Done

Thank you for the stories, Jack. I will miss you.

*Which I go back and fix, because people find blogs long after the fact.

June 6, 2023

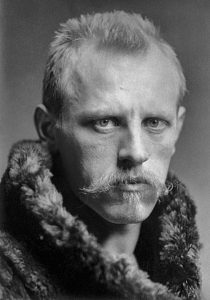

Nansen Passports

Passports, visas, residence and work permits, and journalists’ overseas accreditations have been a recurring thread in my work for the last few years*—the inevitable result of writing about an American journalist who spent much of her life in Europe. Working her way through bureaucratic red tape to be sure she had the correct permissions to go where she she needed to be was a fact of life for Sigrid Schultz. She took it seriously, even when the home office back in Chicago thought she was being fussy, because she knew border officials in Europe took proper documentation seriously.

In the years between the two world war, when Schultz was active, official identity documents were important. Millions of people were left stateless by a combination of the changes that reshaped the map of Europe, the revolutions and subsequent civil war in Russia, the Armenian genocide in the former Ottoman Empire and the constant small-scale wars between the new states created by the peacemakers in Versailles. Without valid passports, homeless refugees found it almost impossible to find asylum in countries that were already in economic distress due first to the ravages of war and later to the great depression.

A Norwegian polar explorer turned diplomat named Fridtjof Nansen had successfully organized the repatriation of prisoners of war after World War I. In 1921, the League of Nations named him head of the Office of the High commissioner for Refugees, with a mandate to repatriate the refugees or arrange for them to be distributed between other countries. It soon became clear the many of the refugees couldn’t or wouldn’t return to the countries they had left.

His budget did not allow him to give direct aid to refugees. Instead he proposed a solution that became known as the Nansen passport—a certificate issued by the country in which the homeless had taken refugee that served as both a valid form of identification and a travel permit. The passport did not grant its holders citizenship, but it allowed them them to cross borders in search of work and family members and protected them from deportation.* It was ultimately recognized by 52 countries.

Roughly 450,000 refugees, most of them Russian and Armenian, carried Nansen passports between between 1922 and 1942.

*It also provided governments with a tool for tracking refugees. Identity documents always have a dark side.

June 2, 2023

And Speaking of X-rays….

Several of you responded to my recent post on the subject with interesting information about the early use of x-rays.*

This story caught my imagination for several reasons that will be obvious to those of you who are regular visitors here on the Margins:

Madame Curie in a mobile x-ray unit ca. 1915

When World War I broke out in 1914, Marie Curie (already a two-time Nobel Prize winner) relocated her precious supply of radium (one small ounce) from Paris to Bordeaux. Then she considered how she could best serve her adopted country in wartime.

Doctors in major cities were already using x-rays to view broken bones and locate foreign substances in the human body. Combatant nations quickly established radiology units in rear-area hospitals, but were slower to recognize the importance of x-ray units near the frontline, where a fast, accurate assessment of a wound allowed for quicker and more precise surgery, and better recovery rates.

Recognizing that the available services were inadequate, Curie leveraged her reputation to secure an appointment as the head of the radiology auxiliary to the Military Health Service. Then she convinced wealthy acquaintances to donate money and cars, automobile shops to refit the cars as vans, and manufacturers to provide x-ray equipment. She learned to drive a car and gave herself a quick education in anatomy, x-ray operation, and automobile repair.

By late October, 1914, the first 20 mobile radiology units, which French soldiers dubbed petites Curies,** were ready, manned (and in many cases womanned) by a team made up of a doctor, an x-ray technician and a driver. Madame Curie herself, with her seventeen-year-old daughter Irene as her assistant, drove one of the units to the battlefield.

By the end of the war, France had more than 500 stationary x-ray stations and some 300 mobile units, with 800 male technicians and 150 women trained by Madame Curie and Irene in an intensive six- to eight-week course at the Radium Institute in Paris.

At war’s end, the French government gave Irene a medal for her war work, but did not officially recognize Madame Curie’s role in saving countless soldiers’ lives.

*For more information on the use of x-rays in shoe stores: When X-Rays Were All the Rage, A Trip to the Shoe Store was Dangerously Illuminating

**I am reminded of another woman’s military medical innovation: Isabella of Castile created mobile field hospitals, known as the Queen’s Hospitals.

With hat tips to Paul and Karin for the link and the story.

May 29, 2023

From the Archives: Road Trip Through History–The American Cemetery

It is Memorial Day here in the United States: a time to remember soldiers fallen in our country’s service. Instead of writing a new post on the subject, I’ve chosen to share this post from 2016.

* * *

People often visit the English Cemetery* when they go to Florence. The final resting place of prominent nineteenth century inglesi, including Elizabeth Barrett Browning, the cemetery is by all accounts a beautiful park in a city that already teems with beauty.

It was on our list of possibles, but when push came to running out of time we chose the American Cemetery instead. Where the English Cemetery holds the graves of self-selected nineteenth century expats, the American Cemetery honors an involuntary group of expatriates: 4398 American soldiers who died in the Allied campaign to liberate Italy in World War II. The cemetery site was taken by the US Fifth Army on August 3, 1944 and was subsequently granted for use as an American burial ground by the Italian government **

When I think of Florence and history, I think of the Renaissance. I don’t think about World War II. This is, of course, ridiculous. When you are in Florence, subtle reminders of the war are everywhere. Stories of museum curators and librarians who protected treasures of Renaissance art. Bridges that no longer exist because retreating German forces destroyed all of the bridges across the Arno except for the Ponte Vecchio, which was spared at the last minute.*** (Instead they blocked access by destroying the medieval buildings at either end of the bridge.) Tales of collaboration, resistance and the tricky balancing act in-between.

There is nothing subtle about the American Cemetery, which is made up of seventy acres of beautifully maintained graves and an imposing monument that tells the story of the Allied push from northward from Rome to the Alps. It is breath-taking, impressive, heartbreaking. But the thing that got me right in gut was the guest book. Most of the visitors who signed in were not American but Italian. And in the comments section one of them wrote a single word–grazie. Thank you.

*Yet another historical misnomer, like Prince Henry the Navigator or the Silk Road. The cemetery was founded in 1827 by the Swiss Evangelical Reformed Church and originally named the Protestant Cemetery. But over the course of the century the size of the Anglo-Florentine community grew. So did the number of English (and American) Protestants who needed a final resting place.

** The American Battle Monuments Commission maintains American cemeteries and memorials, including the cemetery in Florence, in sixteen countries.

***Tour guide history attributes this to a personal order from Hitler. I suspect this is comic-book history, but I don’t really know.

May 26, 2023

X-Rays: Earlier than I Realized

A machine gun bullet embedded in a foot bone: x-ray. Photograph, 1914/1918. Wellcome Collection. In copyright

Every book I write leads me down unexpected byways that inform what I write, and even what I think, but don’t actually appear on the page. In the case of Sigrid Schultz, I regularly found myself up against questions of technology. Often I pursued a technical question because I wanted to understand how Schultz and her colleagues transmitted their stories overseas.* (I will admit, I still do not entirely understand how reporters were able to send photographs, maps and other illustrations by radio.) Other times, I was presented with the technical aspects of a story Schultz was covering—these were the days when innovation in general and aviation in particular were hot stuff.

And occasionally I wanted to understand when a particular technology came into existence and how prevalent it was in the period I am working on. In some cases—the microphone for instance—putting a technology into the timeline actually made the story clearer in my head. In other cases, though, I just hit something that spurred my curiosity and sent me down a happy rabbit hole.

For example, Sigrid Schultz casually mentioned having her knee x-rayed after an accident in 1941. I was surprised. Somehow I had assumed, based on no information whatsoever, that x-rays were a later technology. Wrong.

German physicist Wilhelm Roentgen accidentally discovered x-rays in 1895 while testing whether cathode rays could pass through glass.** Roentgen must have also been inclined to travel unexpected byways: after some experimentation he learned that when he projected what he called X (as in unknown) rays toward a chemically coated screen, they could pass through most substances, including human tissue, but would leave shadows of higher density objects, like bones, on the screen. Moreover, the resulting images could be photographed.

News of his discovery, and its potential medical uses, spread quickly. Within a year, doctors through Europe and the United States were using the new technology to view broken bones, kidney stones, bullets, and even swallowed objects without having to cut the patient open. A few researchers, including Thomas Edison and Nikola Tesla, warned of possible dangers from radiation exposure, but they were largely ignored. By the 1930s and 1940s, x-ray technology was so common that some shoe stores offered customers free e-rays of their feet.***

Roentgen won the first Nobel prize in physics for his discovery in 1901.

* They had choices: the mail, telephone, wireless, and cable—and combinations thereof. Which one they chose depended on a complicated trade-off between time and money that varied from story to story. None of the methods were entirely reliable and bureau chiefs like Schultz spent a great deal of time trying to organize ways for correspondents and “stringers” located outside London, Paris and Berlin to get their stories to the home office.

**This is the point at which I realized I didn’t know what cathode rays were and wandered down an adjacent rabbit hole. For those of you who are similarly inclined, this is the most understandable of the sources I found: https://www.thoughtco.com/cathode-ray-2698965

***Why customers would want to see the bones in their feet is not clear to me.