Pamela D. Toler's Blog, page 24

November 23, 2023

On the Road for Thanksgiving

I keep looking for another vintage Thanksgiving postcard, but most of them have creepy children wielding axes and threatening turkeys. Not a good holiday vibe in my opinion.

As I write this, My Own True Love and I are preparing to leave town for Thanksgiving. We’ve wrapped a road trip around a holiday visit to family in Atlanta. We expect to enjoy historical stops along the way, BBQ somewhere in Tennessee, and a rowdy, laughter-filled Thanksgiving feast.

I have a lot to be grateful for this year, including the fact that I am coming to the end on this book that has consumed me for the last four (4!) years. One thing I’m grateful for is those of you who read History in the Margins, whether you’ve been with me from the beginning or found me recently. Having you on the journey with me is a wonderful experience. You comment on posts, share them with your friends, ask me questions, point out typos, send me ideas, and cheer me on. The conversation has been going on for more than ten years now.

There are so many stories out there. Some funny. Some infuriating. All of them fascinating. I look forward to sharing them with you.

____________________________

Speaking of sending me ideas, I am currently issuing invitations to my annual Women’s History Month series of mini-interviews. I have some great people on board already, but I need more. If you “do” women’s history in any format,* or know someone who does, or have an idea of someone you would love to see in the series, let me know.

*I’ve interviewed academics, biographers, podcasters, historical novelists, tour guides, and poets, but would be happy to talk to people who explore women’s history through music, puppet shows, graphic novels, the visual arts, interpretive dance….

November 21, 2023

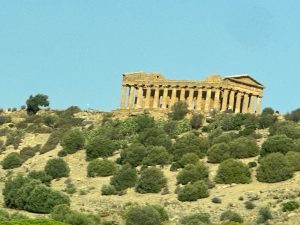

World War II in Sicily

We spent one night in renovated vineyard/ “farm stay” hotel that dated from the eighteenth century. The vineyard operated continuously through World War II, when it was abandoned. It was reopened in 2000. When I asked our Sicilian guide why it had been abandoned, he shrugged and said “So many possible reasons.”

Not surprisingly, World War II was not a focus of our visit. (As I’ve mentioned, several times before, the tour focused on food.) And yet it was never far away. Our guide in Palermo pointed out concrete apartment buildings in the historic district of Palermo— built during a brief period in the 1950s as post war replacements for the baroque-style villas that were destroyed in 1943 when both the Germans and the Allies bombed Sicily. In Siracusa, we learned that Mussolini razed medieval and baroque building to clear a path for his parade through the city. (I’ve not been able to verify this, but there is definitely a swath of ugly post-war concrete buildings through the historic district.*) And German pillboxes scattered the countryside near the coast, much like the Grecian ruins which we saw on many hilltops—a reminder of the past without a specific context.

Faced with constant physical reminders of the war, I began to realize that I didn’t know much about World War II in Sicily. Back home, I set out to learn more. (Does this surprise anyone?) I quickly realized that unless you look at something specifically focused on Sicily, its role in the war is often described as “the doorway to Italy.” In fact, one reference book on my shelf summed up 38 days of hard fighting for control of the island this way: “The Allied invasion of Sicily began on July 9, 1943, and the battle for Italy followed.”

In fact, the Allied invasion of Sicily, known as “Operation Husky,” was a major amphibious operation that gave the Allies a preview of many of the issues they would encounter a year later in the D-Day invasion. More than 3,000 ships landed 160,000 soldiers— the combined forces of British General Bernard Montgomery’s Eighth Army and the US Seventh Army under General George Patton. (Not a pair inclined to play well together.) They were covered by 4,000 aircraft from Malta.

The Nazis believed that the Allied attack would focus on Sardinia and Corsica, thanks to an elaborate misinformation campaign run by the British, known as “Mincemeat”.** As a result, only two German divisions were on the island to oppose the invasion. The German commander, and subsequent historians, dismissed the Italian forces as being of little help—an assessment that may well have been accurate due to Italy’s political instability.

On July 24, Benito Mussolini was deposed and arrested. The new Italian government immediately sued for peace terms with the Allies and withdrew their troops from Sicily the next day. Germany, too, began to withdraw troops across the Messina Straits in order to reinforce their forces in mainland Italy.

Over 38 brutal days, half a million Allied soldiers fought over rocky terrain through at least three defensive lines of the German retreat. The Allies reached the port city of Messina on August 17. They now controlled Sicily, the first section of the Axis homeland to fall to Allied forces in the war and a strategic key to the Mediterranean.

*It is only fair to note that not all post-war concrete buildings, in Sicily and elsewhere, are ugly. Siracusa, for instance, has several stunning examples of Brutalist architecture from the 1950s.

**One of these days I’m going to see if anyone has written about who named the various Allied campaigns and why they chose the names they did.

November 17, 2023

Go For Baroque?

On January 11, 1693, a major earthquake struck eastern Sicily,* Malta, and parts of southern Italy. It was followed by a tsunami that struck the coasts of the Ionian Sea and the Messina straits. More than 60,000 people died as a result of the earthquake; the tsunami killed thousands more. At least 70 town and cities, including Siracusa, were damaged and eight towns in the Val di Noto region were totally destroyed. It was possibly the most powerful earthquake in recorded Italian history.

Depiction of the earthquake in an engraving from 1696

The earthquake changed the landscape of Italy in more ways than one. The reconstruction that followed was shaped by a generation of local architects commissioned to rebuilt palaces, villas, and churches throughout the region, many of whom had trained under the great Baroque architects in Rome. Baroque buildings added an new ingredient to what one of our guides described as the “lasagne” of Greek, Roman, Byzantine, Muslim and Norman styles typical throughout Sicily

The eight towns in the Val di Noto, in particular, were rebuilt in what became known as “Sicilian Baroque,” which added grinning masks, chubby putti, and decorated balconies to the flamboyant curves and flourishes of typical of Baroque architecture. The rebuilt towns are now a UNESCO world heritage site due to the time-capsule feel of towns built in a single style at a single time. The guides, the historical markers, and to a lesser degree the UNESCO website, focus on the towns’ homogeneity and the high architectural and artistic quality of the rebuilt towns.

The cathedral of San Giorgio in Modica, built after the earthquake

*Then part of the Spanish Empire, for anyone trying to keep track of the timeline.

November 14, 2023

From the Archives: An Islamic Map for a Christian King

When we last left Sicily, the Roman Republic had taken Siracusa, which became the capital of Roman government in Sicily. The Romans held Sicily for 300 some years. The island was subsequently occupied by the Byzantine empire in 535 CE, Arabs from North Africa in 965 and the Normans in 1060. *

Under the Normans, Sicily enjoyed a brief period of Christian-Muslim synergy similar to that occurring in Spain at the same time. Here is one of my favorite stories from that period, which first ran in 2013.

Most maps made in twelfth century Europe were based on tradition and myth rather than scientific information. The only practical maps were mariners’ charts that showed coastlines, ports of call, shallows and places to take on provisions and water. Roger II, the Christian king of Sicily, wanted a map of the known world that was a factual as a mariner’s chart. In 1138, he hired well-known Muslim scholar al-Sharif al-Idrisi to collect and evaluate all available geographic knowledge and organize it into an accurate picture of the world.

For 15 years, al-Idrisi and a group of scholars studied and compared the work of previous geographers. They interviewed the crews of ships who docked at Sicily’s busy ports. They sent scientific expeditions, including draftsmen and cartographers, to collect information about relatively unknown places.

Finally, al-Idrisi was ready to make his map. He began by making a working copy on a drawing board, using compasses to accurately site individual places. The final copy was engraved on a great silver disk that was almost eighty inches in diameter and weighed over 300 pounds. Al-Idrisi explained that the disk was just a symbol for the shape of the world: “the earth is round like a sphere, and the waters adhere to it and are maintained on it through natural equilibrium which suffers no variation”

Al-Idrisi’s map was accompanied by a descriptive geography that contained all the information his college of geographers had collected. Its formal name was Nuzhat al-Mushtaq fi Ikhtiraq al-Afaq, or The Delight of One Who Wishes to Traverse the Regions of the World. It was more commonly known as Roger’s Book.

In 1160, the Sicilian barons revolted against Roger’s son, William. They looted the palace and burned the library, including Roger’s Book. Not surprisingly, the silver map disappeared. Al-Idrisi fled to North Africa with the Arabic text of Roger’s Book. His work survived in the Islamic world, but it was not available in Europe again until the Arabic text was printed in Rome in 1592.

* Six years before William the Conqueror, aka William the Bastard, invaded and conquered England.

November 10, 2023

In which I take a side trip in time and space to consider the Mayans, the Aztecs and Chocolate

During our visit to Antica Dolceria Bonajuta, the artisanal chocolate producer in Modica, our guide emphasized the fact that most modern chocolatiers, who use heat based methods such as conching and tempering to create smooth chocolate with a shiny appearance. By contrast, the Bonajuta chocolate makers still used a traditional “cold-processing” method similar to that used in Mesoamerica. in which cacao beans were roasted on a metate ( a rock grinding stone) that was heated over charcoal and then pounded into a paste.

Cacao beans, and the cold-processing method arrived in Modica during the period of Spanish rule, which began soon after Spaniards invaded the Aztec empire and discovered chocolate, not only the cacao bean itself, but the highly flavored beverage served in the court of the Aztec emperors.

The cacao tree is native to Central America. It only grows in tropical areas with a temperature above 60 degrees Fahrenheit and year round moisture. In its raw state the cacao bean grows in pods on the trees known botanically as “theobroma cacao,”from the Greek word for “food of the gods” and the Mayan word for the bean itself.

The Mayans* domesticated the cacao tree and grew it both in home gardens and in large commercial plantations. They venerated the beans as a gift of the gods, using them in religious ceremonies and for healing. Pots full of chocolate drink were included in the burial goods of important people. They also traded the beans throughout Central and South America as a valuable commodity. In fact, they had a god named Ykchaua who was the patron of cacao merchants. They roasted the beans and used them to make spicy, bittersweet drinks, gruels, and porridges that they flavored in a variety of ways.

By the time of the Aztec empire,** the cacao plant was so highly valued that the beans were used as currency. One hundred cacao beans was one day’s wages for a porter. The same amount could buy a slave or a hare. Three beans would buy an egg or an avocado. One bean would buy a tomato.. The beans were valuable enough that people would make counterfeit beans or mix them with less valuable material.

One reason the beans were so valuable is that the Aztecs could not grow the tropical cacao tree in the temperate highlands near their capital. Cacao beans became the object of both trade and war. When the Aztecs conquered tropical lowland areas of the Gulf Coast from Vera Cruz to the Yucatan, tribute was often paid in cacao beans. In the reign of Ahuitzotl (1486-1502), the Aztecs conquered the province of Xoconochco specifically because it was famous for the production of high quality cacao. One of the most important areas of cacao production, the Chontalpa of Tabasco, never became part of the Aztec empire. The only way the Aztecs could get cacao beans grown in the huge Chontalpan cacao plantations was by traveling to the Chontalpan trading city of Xicallanco, which drew long distance traders from all over Mesoamerica.

The importance of cacao and other luxury products in Aztec society can be measured by the status of the long distance traders, called pochtecas. Aztec society was very stratified and the pochtecas enjoyed a high rank. There were twelve pochteca guilds in the empire, each with its own headquarters and warehouses. Membership was hereditary. The pochtecas were described and treated as warriors because their work was so dangerous. They often traveled through hostile territory to reach the markets where they purchased luxury goods for the royal house and the nobility. In addition to cacao, they traded for beautiful feathers, jaguar skins and amber.

In addition to rules about who could be a long distance trader, Aztec society had heavy restrictions on who could use or consume the luxury products that the pochteca brought back. One of the luxury goods governed by these sumptuary laws was “xocolatl” (pronounced “shoco-latle”) or “bitter water”, a cold beverage made from cacao beans that had been ground into a paste and flavored with chilies, herbs, or honey. (The Mayans, by contrast, preferred their cacao hot.) Only the royal family, nobility, warriors and long distance traders were allowed to drink it. A Spanish chronicler named Bernal Diaz del Castillo recorded that more than 2000 containers of chocolate with foam were drunk every day by Montezuma’s guard alone. The other high ranking people in Aztec society, the priests, are not included in the lists of chocolate drinkers, possibly because the priesthood were expected to live in strict austerity.

The only commoners who ever had a chance to taste chocolate were soldiers on the march. Ground cacao made into wafers was issued to every soldier on campaign as part of the military rations, along with toasted maize, maize flour, toasted tortillas, ground beans and bunches of dried chilies.

The sixteenth century Franciscan missionary, Fray Bernardino de Sahagún, listed nine different chocolate drinks served to the emperor in his twelve volume book on the Aztecs, A General History of New Spain. They included “green cacao-pods, honeyed chocolate, flowered chocolate, flavored with green vanilla, bright red chocolate, huitztecolli-flower chocolate, flower-colored chocolate, black chocolate, white chocolate”. In addition to vanilla, honey and cinnamon, the drinks were flavored with spices such as hot chilies, anise, achiote, and allspice. It was poured from container to container to produce stiff foam that was an important element of the drink. It was served at the end of a meal, like a dessert.

The Spaniards brought back cacao beans alongside other treasures, but the bitter beverage was slow to catch on in Europe until the Spanish added sugar—which arrived in Europe from Southeast Asia at much the same time.*** Once it was sweet, chocolate became a popular luxury item in Europe.

*Just to give you a sense of the timeline, because even chocolate needs context: The classic Mayan civilization flourished from around 250 to 900 CE. In the ninth century, the Mayan culture suffered from a major political collapse, in which cities were abandoned. A reduced version of the culture, marked by independent provinces that shared a common culture, survived to the eve of the Spanish conquest. The final independent Mayan city fell to the Spanish in 1697.

**The Mexica, as the Aztecs called themselves, are believed to have been a nomadic people who migrated into central Mexico in the thirteenth century and founded the city-state of Tenochtitlan in 1325 CE. In 1428, the Mexica allied with two other city-states, forming the Aztec Triple Alliance and the beginnings of what we know as the Aztec Empire. The Spanish, led by Hernando Cortez, arrived in 1519. Two year later, after a bitter siege, the Aztecs surrendered and Cortez began to build a new city on the ruins of Tenochtitlan.

***The relationship between imperialism and food is long and complicated.

November 7, 2023

Cheese, Chocolate, and Siracusa

Our second stop in Sicily was the city of Siracusa, which is a history nerd’s delight, or more accurately would have been a history nerd’s delight if we had been on a different kind of tour. (Two areas of the city are UNESCO World Heritage sites.) Instead of spending our time at the city’s archeological park and museum, we visited a small producer of farmstead cheeses near Calascibetta one day and an artisanal chocolate producer that has been in business in Modica since 1880 the following day.*

Nonetheless we managed to get peek at the city’s rich history as we went past. As in Sicily as a whole, a series of foreign conquerors took the city over the centuries and left their mark without totally obliterating the cultures that came before. It is clear, even from the passing glance we managed, that Siracusa’s moment of historical glory was during the classical period, when it was one of the most important cities of the Hellenic world. Here are the bits that stuck with me:

Siracusa was founded in the eighth century BCE by settlers from the Greek city-state of Corinth and became a city-state in its own right. By the fifth century BCE, it rivaled Athens in size.It was the birthplace of the mathematician and engineer Archimedes (c 287-212 BCE), who derived an approximation of pi, was one of the first to apply mathematics to physical phenomenon, articulated the law of buoyancy (known as Archimedes principle), and invented several machines, including an innovative screw pump.** He also designed a number of weapons that were used to defend the city when it was besieged by Romans. A Roman soldier killed Archimedes during the siege despite orders by the Roman proconsul Marcus Claudius Marcellus that he not be harmed, because obviously such an inventive scientist would be an asset to the Roman Republic.The Romans successfully took the city in 212 BCE. Siracusa became the capital of the Roman government in Sicily and remained the most important city in Sicily until Palermo became the capital of the Norman kingdom of Sicily in 1130.As was so often the case, conquerors used their predecessors monuments as quarries for building materials. The most notable example of this in Siracusa is the cathedral, which was built in the seventh century, when Siracusa was under Byzantine rule. Stone pillars from a fifth century BCE temple to Athena are integrated into the walls and shape the floor plan. Its facade was rebuilt in the baroque style after an earthquake in 1693 damaged the city.***

Roman amphitheater in Siracusa, part of the UNESCO World Heritage area

*No complaints here. We learned a lot about how both products were made and enjoyed meals centered onthem. Saffron cheese! Ricotta made that morning! An amazing cold chocolate drink! I must admit, after a four course lunch that included chocolate in every course I was not interested in eating chocolate again for several days.

**Spoiler alert, the Archimedean screw will appear in a blog post coming to this site.

***You’ll be hearing more about that earthquake as well.

November 3, 2023

The Unexpected Legacy of the Carob Seed

As those of you who also read my newsletter already know, My Own True Love and I recently got back from a ten-day tour in Sicily. The tour focused on food, not on history, but you can’t keep history nerds from noticing history, especially in a cultural melting pot like Sicily, which at various times was controlled by the Phoenicians, the Greeks, the Romans, Goths and Vandals, the Byzantines, Muslims from North Africa, Normans, and Spain.

Our first day in Sicily included a walking tour of Palermo, on which we were introduced to the carob tree, and more importantly from my perspective, the carob pod.

Most of us know carob as an unsatisfactory substitute for chocolate—made by drying, roasting and grinding the pulp found inside the pods— that was foisted on us in the name of health. In addition, the seeds are the source of a widely used thickening agent that is used in commercially prepared foods, including ice cream.

That is not what caught my attention, however. In the days before standardized weights and measures, carob seeds were used by traders around the Mediterranean as a standard for weighing small valuable items, particularly gemstones. The story is that the seeds are relatively consistent in size: 0.2 grams or 1/150th of an ounce.* Certainly they were readily available throughout the Mediterranean, where the tree is commonly found. The average weight of the carob seed, once known as carats, from the tree known as Ceratonia Selequia,** became the standard measure for gemstones: the carat.**

Who knew?

*Scientific studies demonstrate that this isn’t necessarily true. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1686184/

**Pronounce Ceratonia with a hard c, as is proper in Latin, and the relationship will be clear.

October 31, 2023

From the Archives: Orson Welles’ The War of the Worlds and the History of Radio Broadcasting

You’ve probably heard this story before:

On October 30, 1938, a 23-year-old theatrical boy-wonder named Orson Welles caused panic among radio listeners with the Halloween episode of his Mercury Theatre on the Air: an adaptation of H.G. Well’s The War of the Worlds.(1) Actors played the roles of correspondents who broke into an on-going [fake] radio program, seeming to report live as Martians invaded and destroyed the real life town of Grovers’ Mill, New Jersey. As the fictional invaders began to move toward Newark and then New York City, these “correspondents” told their audience that they were reporting from military command posts and from the roof of a broadcasting building in Manhattan.

Some listeners believed the show was a live broadcast and panicked, even though the opening of the show made it clear that the one-hour program was a drama.(2) A Princeton study published in 1940 claimed that six million people heard the program, and 1.7 million believed it was a real news broadcast. (Subsequent scholars question both numbers.)

As for me, I’ve always wondered why anyone would believe the broadcast was real, but as I learn more about radio in the 1930s it makes more sense. Radio was relatively new—the first national broadcast networks in the United States were incorporated in 1926 (NBC) and 1928 (CBS). News broadcasts were even newer, and infrequent. Stopping a program for “breaking” news was almost unheard of.

The growth of Nazi Germany changed the nature of broadcast news The first “news roundup” from multiple locations occurred in March, 1938, in response to the German invasion of Austria. Working on short notice, with serious technical difficulties, Edward Murrow and William Shirer of CBS cobbled together a half-hour of American newspaper correspondents commenting on the invasion from London, Vienna, Berlin, Paris and Rome. Listeners were enthralled.

When the Munich Crisis broke out that September, both NBC and CBS upped their coverage, broadcasting live from Europe 147 and 151 times respectively over the course of three weeks. Back in the United States, CBS’s primary news reader, H.V. Kaltenborn (3), held the story together for his listeners in 102 broadcasts that ranged from one-minute bulletins to two-hour marathons in which he simultaneously translated speeches from French and German. America stayed glued to the radio throughout the crisis.

The crisis ended, but the role of radio news was changed. Local radio stations increased the time they devoted to broadcasting the news and networks scrambled to expand their overseas coverage.

As a result, when Welles broadcast The War of the Worlds a month after the crisis in Munich, he reached an audience that was newly attuned (literally and metaphorically) to radio news, but was not yet sophisticated enough about the medium to tell fact from fiction.

(1) Am I the only one to just now notice the juxtaposition of Orson Welles and H.G. Wells in this event? Meaningless and yet curious.

(2) One scholar suggests that some people missed the beginning because they were channel surfing. Let this be a warning to you.

(3) I hadn’t heard of him either until I started working on this book. At the time, he was a Big Deal.

October 27, 2023

Around the World in Eleven Years

And speaking of memoirs about living in Nazi Germany, as I believe we were, allow me to introduce you to Around the World in Eleven Years, possibly the most unusual memoir of the period.

Published in 1936, the book was purportedly written by eleven-year-old Patience Abbe with occasional input her younger brothers Richard, and John. According to family lore, as reported in Abbe’s obituaries in 2012, the book was inspired by their mother, actress and former Ziegfeld girl Polly Abbe, who transcribed the children’s stories. Around the World in Eleven Years tells the story of the children’s nomadic childhood in Europe, following their father, photographer James Abbe, from France to Germany, Austria, Russia and England, returning “home” to the United States for the first time when Patience was eleven.

The book was an immediate best-seller, going through sixteen printings in its first year, perhaps because readers were eager to read what the reviewer in the Los Angles Times described as a “chronicle of rollicking kids” that smoothed the edges off the increasingly difficult news from Europe.*

James Abbe was one of the best known photographers of the 1920s and 1930s. He originally made his name as a stage and film photographer with portraits of Hollywood stars such as Mary Pickford, Charlie Chaplin and Lillian Gish. In the late 1920s James turned increasingly to photojournalism. His work included an exclusive photo session with Stalin in the Kremlin, documenting the rise of the Nazis in Germany, and images of the Spanish Civil War.

While there is no doubt that at least one adult, and probably several, edited Patricia’s stories, they retain a child’s eye view. Around the World in Eleven Days offered readers an innocent but sharp-eyed counterpoint to James Abbe’s photographs. In it, “I, Patience” described a Nazi march, in which her mother got entangled and crossing the Russian border with her father’s negatives wrapped around her brother’s bellies so the Soviets didn’t seize them. She talked about going to school in Nazi Germany, where they had to salute their teachers and say “Heil Hitler!”, and in Russia where she learned a communist version of “London Bridge is Falling Down.” She also shared her impressions of the people they met, including Sigrid Schultz:** “Aunt Sigrid is a little lady with golden hair and blue eyes and beautiful teeth. She is always smiling…She helps lots of people and speaks four languages. She is also very chic and always had parties and Mamma used to go to them all the time.” Sigrid Schultz in a nutshell.

Once back in America, the Abbe family traveled cross country from New York to Hollywood, where they finally made their home. Instead of meeting politicians and foreign correspondents, they met movie stars. (Patience once danced standing on Fred Astaire’s shoes for a photo shoot.)

Patience (or possibly Polly) ended the book with their dreams for further travels: “We would go to China. Richard wants to see the gold on the King’s house in China. Johnny wants to see the robber. I, Patience, want to see everything.” Hard to disagree with that, Patience.

**Just to put it in context here are a few high points, or low points, in the news in 1936 for those of you who don’t have the chronology in your head:

❦ March Hitler sent troops into the demilitarized Rhineland zone and renounced the Locarno, finally destroying any illusion that Germany would honor the Versailles treaty. It was Hitler’s first military action.

❦ May Italy conquered Ethiopia.

❦ July The Spanish Civil War began.

❦ August Berlin hosted the Olympics, presenting a whitewashed view of Nazi Germany to the world

❦ Also August In Russia, the dramatic trials began that would develop into Stalin’s first round purges, known as the Great Terror

❦ October Hitler and Mussolini signed the first of several treating, creating the

Not a good year, with worse to follow. (In a recent post I promised to try to use “horticultural dingbats” here on the blog. I found they were too fussy to replace asterisks but are a more gentle choice than “bullets” for a list. Though bullets might be the appropriate choice for this particular list.)

** You knew there was a reason I read this book.

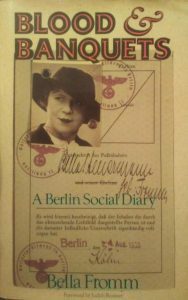

October 24, 2023

Bella Fromm’s Berlin Social Diary

Over the last four years, I’ve read a lot of memoirs and diaries written by people who lived in Berlin in the period between the two world wars. They are a wonderful source to use to enrich a story. They not only allow you to look at incidents from different perspectives but, depending on the author, they can give you details that it is impossible to get any other way. *

Most of the memoirs I used were written by American foreign correspondents stationed in Berlin. One memoir stands out because it was written from a different perspective: Bella Fromm’s Blood and Banquets: A Berlin Social Diary, published in 1942 once she was safely in the United States.

Bella Fromm (1890-1972) was a member of a family of wealthy Jewish wine merchants with long standing roots in Germany and connections with highest ranks of German society, including the Bavaria royal family. The inflation that wracked Germany’s economy in 1923 destroyed the family fortune. Forced to look for work, she used her family social contacts to get a job as a reporter with the Jewish-owned Ullstein conglomerate, one of the largest publishing companies in Europe.

At first, like most women reporters of the period, she worked primarily as a social reporter, aided by her contacts throughout Germany society. But she was talented and ambitious, and those same contacts that got her into the big social events also gave her access to government and diplomatic circles. She soon began writing about politics in addition to parties.

Within months of Hitler’s appointment as chancellor, Germany no longer had a free press. The Nazis shut down hundreds of opposition newspapers. They seized papers owned by the communist and Social Democratic parties as well as Jewish-owned publishing companies, including Ullstein. The few “independent“ papers that survived were effectively under the control of the Propaganda Ministry.**

Fromm’s position as a journalist was increasingly precarious, though she was protected to some extent by her friendships with foreign diplomats and conservative members of the Nazi government. After 1934, when the Nazis seized the Ullstein companies, she was no longer able to publish under her own name, though she continued to publish some articles without a byline.

Unable to support herself entirely by journalism, she returned to her family business as a wine merchant. She sent her daughter to the United States in 1933, but stayed in Germany as long as she felt she could use her contacts to help other German Jews get visas. She finally left in September 1938, after Jews were excluded from the wine trade, leaving her without an income.

At the time of its publication, Blood and Banquets was promoted as a secret diary smuggled out of Germany under the Nazis noses. Some scholars now believe it was written in the United States after she left Germany.*** Nonetheless, it remains a useful picture of life in Berlin from the perspective of a German-Jewish journalist.

*I wrote about this at some length in my newsletter back in May, 2021, if you want to know more.

**There’s a reason freedom of speech is the first amendment in the United States Bill of rights. A free press is a cornerstone of democracy.

***One of the arguments they use to suggest that she was not particularly important is that she does not appear in William Shirer’s Berlin Diaries, which was a huge success when it was published in 1941 and continues to be widely read, unlike the memoirs of many of his contemporaries. By that standard, many people would be erroneously dismissed as unimportant. What’s more, Shirer does not appear in Fromm’s book. They ran in different circles.****

****Sigrid Schultz, who appears to have known everyone, appears in both books.