Pamela D. Toler's Blog, page 124

November 1, 2013

Déjà vu All Over Again: Closing the Border

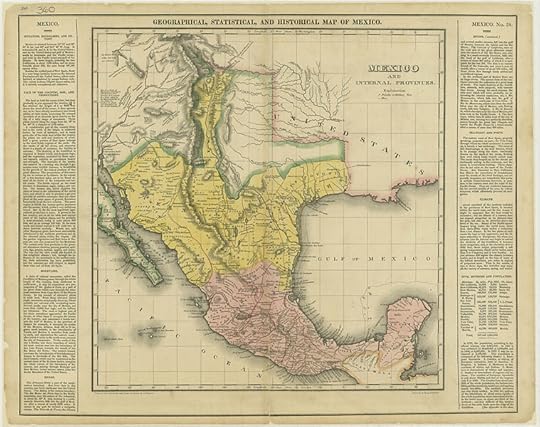

Concerns that immigrants flooding across the border threaten the nation’s basic institutions. Construction of armed posts to defend the border. Passage of new, more restrictive immigration laws. Sound familiar? Welcome to Mexico in 1830.

The story began when Mexico won independence from Spain in 1821. At first the newly independent country welcomed settlers from the United States. The government signed contracts with immigration brokers, called empresarios, who agreed to settle a set number of immigrants on a set piece of property in a set amount of time. In exchange for the right to buy land, settlers agreed to obey Mexican law, become Mexican citizens, and convert to Catholicism. At the same time, the US Congress passed a new land act that made emigration to Mexico even more appealing. Public land in the US cost $1.25/acre*, for a minimum of eighty acres and could no longer be bought on credit. Public land in Mexico cost 12 1/2¢/acre and credit terms were generous. Not a hard choice for anyone who was cash-poor and land hungry.

Some empresarios brought in groups of settlers from France or Germany. More, including Stephen Austin,** brought in settlers from the southern United States. Most new colonists settled in new communities east of modern San Antonia. By the mid-1830s, Anglo settlers outnumbered native Tejanos by as many as 10 to 1 in some parts of Texas. These settlers brought the culture of the American South with them, including slaves and slavery.*** In addition, many Anglo settlers traded (illegally) with Louisiana rather than with Mexico.

Concerned about growing American economic and cultural influence in the region, the Mexican government passed a law banning immigration into Texas from the United States on April 6, 1830. They also assessed heavy customs duties on all US goods, prohibited the importation of slaves, built new forts in the border region and opened customs houses to patrol the border for illegal trade.

The law didn’t have the intended affect. Instead of re-gaining control over Texas, Anglo colonists and the Mexican government were in constant conflict. The law was repealed in 1833, too late to staunch the wound. The first shots in what would become the Texas War of Independence were fired on October 2, 1835.

*$31.44 in today’s currency. Still a bargain.

** Hence Austin, Texas. (I don’t know about you, but I’m always curious as to how a town got its name.)

***Outlawed in Mexico is 1829–so much for obeying the laws.

October 29, 2013

A History of Britain in Thirty-Six Postage Stamps

I love Big Fat History Books, full of footnotes (no endnotes, please) and academic caution. But I also love small, idiosyncratic books about history: books that look at the past through one person’s obsessions and interest.

Chris West combined an uncle’s Edwardian stamp collection with his own interest in history to create a quirky and insightful approach to the past in A History of Britain in Thirty-Six Postage Stamps.

Taken together, the stories of individual stamps tell the larger story of British history. West begins with the world’s first postage stamp, the Penny Black of 1840, which becomes an emblem of the energy and invention of Victorian Britain. He ends with the 2012 First Class stamp and a thoughtful discussion of whether Britain is still “first class” (the inevitable postage pun is his). In between, he considers a number of recurring themes suggested by the stamps themselves: industry, social change, the role of the royal family, and Britain’s post-war decline and subsequent reinvention(s).

West builds a large historical framework on his “thirty-six little pieces of paper”, but he always brings the discussion back to the stamps themselves. He uses details about designs and designers to further illuminate changes not only in taste but also in the national spirit. The book ends with philatelic information about each stamp, including hints for beginners, more detailed information for experts and an occasional description of a rare issue for “the philatelist who thinks they have died and gone to heaven”. This section is written in the same engaging style as the body of the book: even a reader who doesn’t care about stamps as collectibles may find herself drawn into West’s discussion of forgeries, printing errors and rarities.

If you’d like to know more, you can read my interview with Chris West here.

This review appeared previously in Shelf Awareness for Readers.