Pamela D. Toler's Blog, page 29

May 23, 2023

Operation Cornflakes

On February 5, 1945, near the end of WWII, the Office of Strategic Services (OSS) began a widespread propaganda campaign in Germany with the unwitting help of the German postal service.

As a first step, Allied bombers derailed a German mail train, scattering its cargo in the process. A second wave of bombers followed and dropped eight mail bags, each filled with 800 properly stamped propaganda letters addressed to homes and businesses in the northern Austrian towns to which the train made deliveries. The idea was that when the postal service realized the train had been derailed, the Germans would collect whatever mail had survived the bombing, including the faked letters containing propaganda, and deliver it to German homes as regularly scheduled. In most cases, the delivery occurred at breakfast time, resulting in the code name Operation Cornflakes.

In preparation for the operation, OSS operatives collected samples of German mail, including stamps, cancellations, and envelopes, and compiled lists of German names and addresses from telephone directories. Propaganda that traveled through the German mail system included an OSS-produced newspaper that claimed to be the work of a growing German opposition party,* letters supposedly written by Nazi party leaders about Hitler’s ill health, and by generals who wanted to surrender. Together, the pieces were designed to create doubt in the minds of the civilian population and to weaken German morale.

Over the course of the operation, the allies dropped 20 loads of fake mail, with a total of 96,000 pieces of mail. A unit in Rome addressed 15,000 envelopes a week. Groups in Switzerland and England created the newspapers and letters and forged stamps.**

The operation eventually failed because of a typo. The return addresses on the envelopes were all those of legitimate German businesses. An OSS operative, perhaps with a cramping hand or aching eyes after hours of addressing envelopes, misspelled Kassenverein as Cassenverien on several envelopes. An alert postal clerk caught the error and brought it to the attention of his superiors. The envelopes were opened, and the propaganda discovered.

Did the operation have an effect on German morale? No one knows. But from a strategic perspective, Operation Cornflakes played a valuable role by putting additional strain on Germany’s communication and transport system.

*It is unlikely that any Germans would have believed this, given that the Nazi party had gained control of the German press at all levels within a year of taking power.

**Including stamps that weren’t standard. If you look closely, you’ll notice some creative changes that wouldn’t have passed by an alert censor.

May 19, 2023

Before the Rockettes

The Tiller Girls in an impromptu dance line, 1900

Thirty-six years before the original Rockettes appeared on a St. Louis stage in 1925,* a failed cotton magnate named John Tiller formed a dance troupe that featured quick, perfectly synchronized dance steps. By the 1920s, several dozen troupes of Tiller Girls, selected for uniform height and weight, performed in major cities across Europe. They were so popular that European revue directors formed similar troupes.

Lines of pretty women dancing, or at least posing, had been a staple of variety revues for years. The thing that made the Tiller Girls different from earlier chorus lines was their speed and precision, which many theater reviewers compared to the dynamism of the modern era. Tiller had created a human equivalent of the factory machine, with dancers as interchangeable parts in coordinated kick-lines.

*Yes. St. Louis. The Rockettes first hit Radio City Music Hall in 1932. I was surprised, too.

May 16, 2023

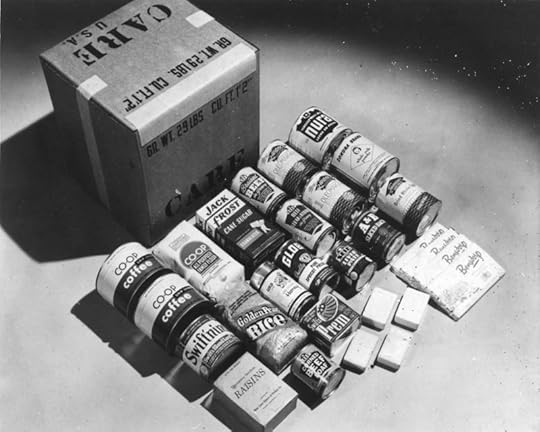

Word With a Past: Care Packages

One of 250,000 CARE packages delivered during the Berlin airlift

When World War II ended, Europe faced a serious food crisis. Millions of people had suffered from malnutrition during World War II.* Cities were destroyed. Agricultural areas were not only ravaged by troop movements, but tainted by the remains of the dead and dying. (In the Falaise Pocket, for instance, it was two years before people could plant crops in the fields because the ground water was polluted with the remains of men and horses. )

The Marshall Plan was designed to help Europe rebuild, but it didn’t deal with immediate need on an individual level.

In November, 1945, seven months after the war ended in Europe and two months after it ended in the Pacific, Arthur Ringwald and Dr. Lincoln Clark worked with 22 American charitable organizations to create a non-profit corporation to send food packages to Europe.** Alice Clark suggested they call it “Cooperative for American Remittances to Europe”: C.A.R.E.

The first C.A.R.E. packages were surplus rations that the U.S. military had been stockpiling in anticipation of invading Japan. C.A.R.E. acquired 2.8 million surplus rations known as “10-in-1”—designed to feed ten men for one day. These boxes included not only canned meats, egg powder and dried milk, but items like coffee, chocolate and sugar which were luxury items to starved Europeans. (Among which we must include the British, who were better off than most of Europe but continued to suffer from shortages as late as 1945.)

The first 15,000 C.A.RE. packages arrived in the French port of La Havre on May 11, 1946—almost exactly a year after V-E Day. By the end of 1946, C.A.R.E was delivering packages in ten European countries. As the supply of rations began to dwindle, C.A.R.E partnered with American food companies to fill its boxes. Americans could send a package to individuals or families for $10. At first the recipients of packages were family and friends of the senders; as the program grew more popular, the organization began to get orders for recipients such as “a hungry occupant of a thatched cottage.”

CARE still exists—the E now stands for everywhere. It still works to eradicate hunger and child malnutritions. But it no longer delivers individual packages to those in need.

For millions of families, C.A.R.E packages were literal life savers in the years after the war, a gift of both food and hope. By the time I was in college, and probably earlier, C.A.R.E packages had evolved into care packages—not quite the same thing but still sent as a token of love and, well, care.***

*An estimated 20 million people died of malnutrition during the war: more than died in combat.

** Herbert Hoover led a similar movement after the first World War. Yes, Herbert Hoover.

***My personal favorite was a package I received long after college. One winter in my late twenties or earlier thirties, I received a box of paperback novels from my parents when I was down with pneumonia. Food for the soul.

May 13, 2023

Joan of Arc and the French Resistance

More than once in the last few years, I’ve stumbled across stories in old issues of the Chicago Tribune that caught my imagination even though they did not deal with my current project.

In recent weeks, this headline from May 13, 1945, grabbed my attention: “FRANCE HONORS JOAN OF ARC AS ‘FIRST PARTISAN’. “

The piece began “The French paid homage today to their national heroine of five centuries , Joan of Arc, who was hailed as the ‘first of the resisitants’ in military, religious and popular ceremonies.” The article when on to briefly describe the ceremonies and to point out that in prior years it had been French royalists who had celebrated the Maid of Orleans, not French republicans.

It seemed to me that with this recognition, the story of Joan of Arc had come full circle.

Over time, the phrase the “Joan of Arc of [fill in the blank]” has become shorthand for a (usually young) woman leading an army against an occupying foreign power. The term has been applied to the solidly historical Ani Pachen of Tibet and the semi-mythical Trieu Thi Trinh of third century Vietnam. The Women’s Era, a popular African American women’s newspaper founded in 1890, called Harriet Tubman “the Black Joan of Arc.” Novelist Henry Miller heard the story of Greek nationalist Laskarina Bouboulina and asked, “How is it we don’t hear more about Bouboulina? …She sounds like another Joan of Arc.” Even at the scale of a besieged city, we find a local heroine described as the “Joan of Arc of Braunschweig.” Each of these women embodied to some degree what Halina Filipowicz describes as the central element of the “Joan of Arc cult”: “a deeply felt need for a democratic hero of unflinching loyalty to a patriotic mission.”

Joan of Arc had long been the model against which other female resistance fighters where measured. Now it seemed the French government had turned the tables by dubbing Joan of Arc “the first of the resistants” rather than naming a woman resistance fighter “a twentieth century Joan of Arc.”*

*I almost typed “the Joan of Arc of France,” but for that doesn’t work for obvious reasons.

May 9, 2023

Twice as Hard

Jasmine Brown is a medical student at the University of Pennsylvania. She completed a masters degree in the history of science, medicine and technology at Oxford as a Rhodes Scholar. As an undergraduate, she founded the Minority Association of Rising Scientists (MARS)—a reaction to the realization that though she was the only black student in her lab she was not the only black student at her university.

Brown is also the author of Twice as Hard: The Stories of Black Women Who Fought to Become Physicians, From the Civil War to the 21st Century. In some ways, Twice as Hard is the historical equivalent of MARS. By linking the experience of black women* as medical students and then as doctors across time, she creates a lineage of role models for students like herself. At the same time, she examines the double burdens of systemic sexism and racism through a very specific lens.

In Twice as Hard, Brown tells the stories of nine black women who became physicians in spite of both personal and social obstacles. The first, Dr. Rebecca Lee Crumpler, graduated from medical school in 1864—27 years after the first black man and 15 years after the first white woman obtained their degrees. The last, Dr. Risa Lavizzo-Mourey, is only a few years older than I am—a fact that struck home how far we still have to go in combating systemic racism in our society. Brown details each woman’s challenges and celebrates her accomplishments. (I was particularly taken by the story of Dr. Dorothy Ferebee, who joined forces with other female students in her program across racial and religious divides to confront sexism.) She not only weaves in the historical context for each woman’s story, but compares it to the experiences of black women medical students today.

The end result is a powerful, and often enraging, account of social barriers and women who surmounted them—and a reminder that barriers still remain.

*Brown uses black with a lower case and African American interchangeably throughout the book to describe the women she writes about.

April 28, 2023

From the Archives: The Ballet that Caused a Riot

This weekend I walked away from desk–deadline or no deadline–to go the ballet. The Joffrey Ballet performed The Little Mermaid–a version that had nothing to do with Disney and everything to do with Hans Christian Anderson. The performance was dark, brilliant, and demanding. We came away exhausted. Now I’m back at work at The Book, which is also demanding. May 1st is just a few days away. (Wish me luck!)

In the meantime, here’s a post from 2013 about another ballet that was dark, brilliant and demanding.

On May 29, 1913, an excited audience, fashionably dressed according to poet and filmmaker Jean Cocteau* in “tails and tulle, diamonds and ospreys,”** waited for the curtain to rise at the Theatre des Champs-Elysées. Serge Diaghilev’s Ballet Russe was premiering a new ballet with choreography by Nijinsky and music by Igor Stravinsky– The Rite of Spring.

On May 29, 1913, an excited audience, fashionably dressed according to poet and filmmaker Jean Cocteau* in “tails and tulle, diamonds and ospreys,”** waited for the curtain to rise at the Theatre des Champs-Elysées. Serge Diaghilev’s Ballet Russe was premiering a new ballet with choreography by Nijinsky and music by Igor Stravinsky– The Rite of Spring.

The Ballet Russe was a breeding ground of early twentieth century modernism.*** Diaghilev produced work that was innovative, exciting, challenging. The music for Stravinsky’s two previous ballets, The Firebird and Petrouchka had been agreeably avant-garde, just enough to make the fashionable crowds who attended the ballet feel proud of their sophistication but not enough to be unenjoyable.

The Rite of Spring, subtitled Scenes of Pagan Russia, was a different pair of toe-shoes. When the curtain opened, the audience saw the dancers sitting in two circles in a wasteland scene dominated by massive stones. When the music began, the dancers moved: knees bent, toes turned in, stamping and stomping in a dance style that was the antithesis of classical ballet. The music and dance alike were dissonant, brutal, and self-consciously primitive, telling the “story” of a pagan rite in which a chosen victim dances herself to death as a sacrifice for the spring will come.

The fashionable audience hissed and booed, primitive in their own way. Soon the noise from the audience drowned out the orchestra. The dancers couldn’t hear the music on stage; Nijinsky shouted out the count from the wings to help them keep time. Artist Valentine Gross, whose sketches of the Ballet Russe were on display in the lobby, later wrote, “The theatre seemed to be shaken by an earthquake. It seemed to shudder. People shouted insults, howled and whistled…There was slapping and even punching.”

Maybe not a riot by soccer standards, but pretty shocking for a night at the ballet.

* Best known today for the film Beauty and the Beast (1946).

**Large artificial plumes, not large fish-eating birds of prey.

***Over the course of his career, Diaghilev would commission librettos by Cocteau, sets by Picasso, Braque, and Matisse, and music by Ravel, Satie, and Stravinsky.

April 25, 2023

Jane Matilda Bolin: Another Guest Post by Rebecca Bratspies

I am delighted to have Rebecca Bratspies back with another story about a woman who deserves to be remembered.

On July 22, 1939 Mayor Fiorello LaGuardia appointed Jane Matilda Bolin to the New York City Domestic Relations Court (now the Family Court). This made Bolin the very first Black woman to serve as a judge in the United States. (LaGuardia was himself the first Italian-American to serve in Congress, and the second to be a mayor of a major US city. )

The appointment reportedly came as a surprise to Bolin. She was just 31 years old and had been working for the last two years as a lawyer assigned to the Domestic Relations Court on behalf of the City. On the fateful day, Mayor LaGuardia summoned Bolin, along with her husband and fellow attorney Ralph Mizelle, to the City of New York Building at the 1939 World’s Fair in Flushing, Queens. Bolin in fact thought she was about to get a reprimand of some kind. Instead, LaGuardia held a swearing-in ceremony.

LaGuardia emphasized that Bolin’s appointment, like all his other appointments, was made based on merit. While “merit” has recently become a code-word for anti-diversity efforts, LaGuardia meant the phrase differently. He was stating that the lack of Black officials was due to racism, and that merit-based appointments were an antidote to racial discrimination. Black newspaper coverage of her appointment repeatedly emphasized that Bolin was not appointed because of her race or gender, but in spite of them. There is no question she was eminently qualified.

The New York Times reported her judicial appointment under the headline “Negress Takes Oath of Office.” The Washington Tribune ran the story under the heading “Jane Bolin is Gotham’s First Woman Judge” with the subheading “Wife of D.C. Man Gets Job Paying $12000 yearly for 10 years.”

The pressure on Bolin to “make good” must have been immense. For her first twenty years on the bench, she was the ONLY Black woman judge in the United States. It was only in 1959, with Juanita Kidd Stout’s appointment to the municipal bench in Philadelphia, that Bolin had any company. (For perspective on how recent this all is, Jane Bolin was only two years older than my grandfather, her son is the same age as my mother.)

Before Judge Bolin made history as the first Black woman judge in the United States, she broke through many other barriers.

Bolin held degrees from Wellesley and Yale. Both institutions now proudly claim her, though her experiences at Yale and Wellesley were fraught with racial and gender-based hostility.

At Wellesley, Bolin was one of two Black students. (She had originally hoped to attend Vassar, but was rejected her because of her race.) Even though Wellesley admitted her, the school barred Bolin from living in the dorm with her white classmates. Bolin was forced to find housing off-campus.

Bolin graduated 1928 as a Wellesley Scholar, an honor given to the top 20 students in each graduating class. Despite her academic excellence, Bolin’s college counselor discouraged her from pursuing law school because she was Black. Even her father, himself a lawyer, tried to dissuade her from attending law school, though his concerns stemmed from his belief that women should be shielded from the seamier side of life.

But Bolin had grown up around the law, spending time in her father’s law office, and his shelves of leatherbound law books. Moreover, articles and photos of lynchings published in NAACP’s magazine The Crisis had shocked Bolin to her core, and inspired her to law school, and to public service.

Bolin persisted and after graduating Wellesley, she matriculated at Yale. She was one of three women and one of two Black persons attending Yale Law. Bolin remembered some of her fellow students taking delight in slamming doors in her face. Bolin reminisced that years later, after she was a judge, one of those very students later invited her to speak to his Texas ABA group. She declined.

Despite the hostile climate, in 1931 Bolin became the first Black woman to graduate from Yale. She was admitted to the New York Bar in 1932, and became the first Black woman to join the New York City Bar association. Despite her record of excellence, Bolin struggled to get a job. “I was rejected on account of being a woman, but I’m sure that race also played a part.”

In February 1933, Bolin and fellow attorney Ralph Mizelle married in secret for {reasons] (I don’t know what they were but I am confident they had some). Two years later, Bolin and Mizelle announced their marriage to the world and moved in together in the Inwood neighborhood of Manhattan. They briefly practiced law together though Mizelle soon became an assistant solicitor for the Post Office. In 1936, Bolin unsuccessfully ran for State Assembly as a Republican. The next year, she fought racial and gender discrimination to obtain a position with the New York City corporation counsel, the City’s legal department.

This job thrust Bolin into the public limelight. The Black press portrayed it as a significant racial advancement for Black people. Black newspapers began including Bolin on the list of heroes, alongside luminaries like Marion Anderson, Joe Lewis, Gwendolyn Brooks, Richard Wright, and George Washington Carver.

Fun Facts: In 1943, Bolin was part of the committee that welcomed fellow Wellesley graduate Madame Chiang Kai-Shek to Madison Square Garden. The committee chair was John D. Rockefeller Jr. In 1944, Bolin was named as one of Vogue Magazine’s “Women of the Year,” and in 1949 Ebony Magazine featured Bolin on its cover. In 1958, Bolin was included in Who’s Who of American Women.

Judge Bolin was a trailblazer on many work/life issues women still struggle to navigate today. Even though she was married to Mizelle, she continued to use her own name. Newspapers routinely referred to her as “Miss Bolin” (widespread use of the term Ms. only happened when another New Yorker, Geraldine Ferraro, became the Democratic candidate for Vice President of the United States.) Moreover, Mizelle and Bolin had a commuter marriage—he worked in D.C. while she was in New York City. She took maternity leave for the birth of her son Yorke Bolin MIzelle, and then went back to work.

As a judge, Bolin helped racially integrate the city’s child services, ensuring that probation officers were assigned without regard to race or religion, and that publicly funded childcare agencies served children without regard to ethnic background. Although widely respected for her judicial temperament, Bolin did not hesitate to call out racism. She issued subpoenas for police officers accused of beating a Black teenager on his way to school. She wrote a letter to President Roosevelt urging him to support anti-lynching legislation. When her hometown Poughkeepsie feted her as a local hero in the 1940s, she called the segregation in the town’s schools, hospitals, and government “fascist,” and criticized the town for “deluding itself that there is superiority among human beings by reasons solely of color, race or religion.”

In 1966, 27 years after Bolin was appointed to the New York court, Constance Baker Motley became the first Black woman appointed to a federal bench. Both Constance Baker Motley and Judith Kaye, the first woman to serve as Chief Judge of the NY Court of Appeals, cited Bolin as a role model and a resource. President Biden made history when he nominated Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson to the United States Supreme Court in 2021. Brown Jackson was confirmed by the Senate on April 7, 2022, making her the third Black person to serve as an associate justice and the first Black woman. (Of the 117 justices to serve on the Supreme Court, only 6 have been women and only 3 have been Black.) The ugly slurs directed at Justice Brown Jackson in 2021, in terms of her abilities and qualifications, might give a slight window into what Judge Bolin undoubtedly navigated daily.

Judge Bolin remained on the bench for 40 years, only retiring when she hit New York’s mandatory judicial retirement age of 70. The Judicial Council of the American Bar Association honored her for her service. Even after retiring, Judge Bolin continued to serve on the boards of the NAACP, the National Urban League, and the Child Welfare League. She was also a member of the Regents Review Committee of the New York State Board of Regents.

Every legislative session since 2017, New York state Assembly member Jeffrion Aubrey has introduced a bill in the NY State Assembly to rename the Queens–Midtown Tunnel the Jane Matilda Bolin Tunnel in her honor. Count me on Team Name It For Bolin! I cannot think of anyone more deserving of this kind of honor!

Rebecca Bratspies is a longtime resident of Astoria Queens. When not geeking out about New York City history, she is a Professor at CUNY School of Law, where she is the founding director of the Center for Urban Environmental Reform. A scholar of environmental justice, and human rights, Rebecca has written scores of law review articles. Her most recent book is Naming New York: The Villains, Rogues and Heroes Behind New York Place Names.

Big Fun!

April 21, 2023

From the Archives: You Could Look it Up.

As I write this, the deadline for my manuscript is 11 days away. (Eek!) I am deep in revision mode. It’s not a straight line process. I just added 134 words to a chapter from which I need to cut many, many words. Thousands of words. And yet the chapter is better for it. (Though it means I now have to cut an additional 132 words somewhere.) While I revise, here’s a post from 2016 for your amusement. Enjoy!

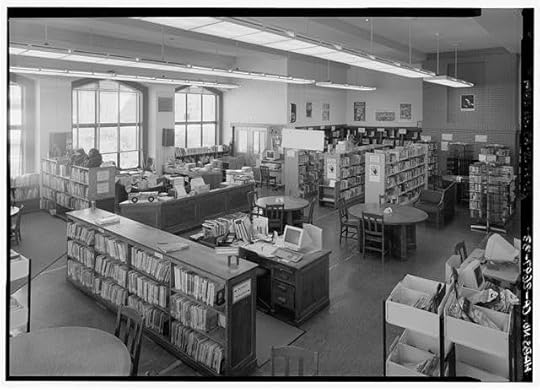

I am a reference book junkie. I collect reference books the way some people collect Fiesta Ware, Oriental rugs, salt shakers, or black pumps.* I argue that they are useful to me in my career. And sometimes it’s true. (The construction dictionary that I bought more than 25 years ago is proving useful in my current project.) But the immediate needs of my writing career provides no explanation for the itch to acquire, for example, an English to Polish dictionary or an encyclopedia of gods or an historical atlas of Byzantium or–well, you get the idea.

I am a reference book junkie. I collect reference books the way some people collect Fiesta Ware, Oriental rugs, salt shakers, or black pumps.* I argue that they are useful to me in my career. And sometimes it’s true. (The construction dictionary that I bought more than 25 years ago is proving useful in my current project.) But the immediate needs of my writing career provides no explanation for the itch to acquire, for example, an English to Polish dictionary or an encyclopedia of gods or an historical atlas of Byzantium or–well, you get the idea.

Thanks to author Jack Lynch, I now have a grander explanation for my fascination with reference books.

In You Could Look It Up: The Reference Shelf From Ancient Babylon to Wikipedia, Lynch argues that reference books are “a civilization’s memoranda to itself”.** In looking at a society’s reference books you learn not only the facts contained therein, but something about what that society valued. (Or what some of a society’s members valued: the annotated list of prostitutes from eighteenth century London, for instance, had a specific audience.)

Each chapter pairs two works dealing with similar topics—words, medicine, games, the arts–and places them in historical context. Lynch begins with the ancient law codes that are our oldest reference books and ends with modern books of trivia, which transform the reference book from a compendium of essential knowledge to an amusement for browsers.

The stories of the individual books are fascinating in and of themselves. (The Guinness Book of World Records began as a promotional item designed to settle drunken wagers in pubs.) But some of the most startling revelations come in the form of what Lynch dubs “half-chapters”, short essays in which he investigates broader topics related to reference books, including the antiquity of complaints about information overload, the relative late adoption of alphabetizing as an organizational structure, and the introduction of deliberate errors by reference book editors.

In the end You Could Look It Up is a history not simply of reference books as a genre but of the broader question of how we organize information and why.

*By which I mean shoes, not the working end of a well. Though I suspect that someone somewhere collects black pump handles. The collecting passion is idiosyncratic, personal, and occasional inexplicable.

**Now there’s an excuse for reference book acquisition!

April 18, 2023

From the Archives: Running on Railroad Time

In case you haven’t heard, I am still deep in book mode. May 1 approaches, and I am doing the revision hokey-pokey. (Put the right words in, take the wrong words out, but the right words, and you shake it all about.) While I turn myself around, here is a post for your amusement that originally ran in 2015. (In blog years that’s eons ago.)

I was recently reading an excellent new book on the Battle of Waterloo(1) in which the author made an off-hand comment about the difficulty of synchronizing accounts even when sources give exact times for events because there was no standardized time.

Until the rise of the railroads in the mid-nineteenth century, time was essentially local. With the exception of the few points where public institutions intersected private schedules,(2) most people’s lives were measured by sun time rather than clock time.(3) Clocks became more important with the industrial revolution and the growth of factories; whole communities found their lives regulated by the factory whistle. But even when two places used the same calendar,(4) there was no way to synchronize their clock towers. More importantly, there was no reason to. The factory in No Place In Particular had no need to match its schedule to the factory in The Town Over The Hill.

That all changed with the railroads.

Railroads were born in Britain in 1825, using technologies developed in the British mining industry. The first public railway, the Stockton and Darlington, carried six hundred passengers over a twenty-six mile line in only four hours on its first trip. Over the next twenty years, investors formed more than six hundred rail companies that together laid more than ten thousand miles of track in Britain–transforming train travel from a novelty to a necessity. As rail travel became more common, differences in local time (sometimes as much as twenty minutes!) became a problem. In 1840, the Great Western Railroad instituted “railway time”. Other railroads soon followed. Some towns resisted bringing their public clocks into line with the railroad,(5) but by 1880 all of Great Britain was using the same time standard, assuming everyone remembered to wind their watches.

The problems were bigger in the United States, where the distances involved and the potential time variations were greater and rugged individualism was the national pastime. By 1840, America had more miles of track than Great Britain. By 1860, it had more railroad track than the rest of the world combined–and was laying more. For the first time it was important for someone in Pittsburgh to know the exact time in Poughkeepsie, Peoria, and Pacific City. If local time differed too much from place to place, people missed trains, trains missed switches, produce rotted. At first, time was regulated on a railroad by railroad basis. Busy stations had to have a different clock for each railroad. It was confusing, It was messy. And it was dangerous.

In 1883, North American railroad officers finally adopted a plan for Standard Time, creating four zones in the United States and one in eastern Canada, based on mean sun times at set meridians from Greenwich, England. (Western Canada was apparently left to fend for itself in terms of time.) Despite some local opposition–the Indianapolis Sentinel complained that people would have to “eat,sleep, work…and marry by railroad time”(see 5 below)– Standard Time became the norm. The Standard Time Act of 1918 belatedly sanctioned existing practice. (I must admit, I wonder what problem required its passage. Was there a town somewhere that simply refused to reset its clocks?)

“Making the trains run on time” remains a synonym for efficiency, Amtrak not withstanding.

(1)David Crane’s Went The Day Well?, one of a flood of new books on the subject because the bicentennial of the battle is nigh.

(2)Think the start of a Christian church service or the Muslim call to prayer. Both of which were publicly and loudly announced in the pre-modern world–church steeples and minarets served much the same function.

(3)At some gut level, we still run on sun time. Who doesn’t remember feeling outraged at the unfairness of being sent to bed while it was still light out on a summer evening? And don’t get me started on Daylight Savings Time.

(4) Not a given, as we’ve discussed before.

(5) Someone is always ready to fight for the status quo, even if it means missing the train.

Image courtesy of ingfbruno, via Wikamedia Commons

April 14, 2023

From the Archives: Madame Lenormand’s Fortune Telling Cards

I am still deep in book mode, with a May 1 deadline bearing down on me–I feel a bit like the heroine in a melodrama who is tied to the tracks and knows the train is coming through the tunnel ANY MINUTE NOW. (Don’t worry. I’m not waiting to be saved, though My Own True Love is making life easier anyway he can.) While I get myself off the tracks, here is a post for your amusement that originally ran in 2018. (Which seems like decades ago.)

* * *

Back in February I spoke at the Civil War Museum at Kenosha, Wisconsin, as part of their annual Civil War medicine weekend. I was a featured speaker, but the heart of the weekend was the 17th Corps Field Hospital–a Civil War reenactment unit from the Midwest that “heals the sick and treats the wounded ‘Under the Yellow Flag'” at events across the country from February through October. Like the best re-enactors, they are accurate and passionate. They are also skilled performers. I urge you to attend one of their events if you get the chance.

As I wandered through the re-enactors’ displays, I passed a woman seating at a small table in the corner. She was dressed in period appropriate-clothing, but her dress was more elaborate than any nurse would have worn and she had no exhibits laid out. “Read your cards?” she asked as I went by.

I needed to distract myself from the inevitable pre-speech jitters,* so I sat down, prepared to be intrigued by tarot cards yet again. To my surprise, I was treated to a history lesson along with my card reading. Instead of using tarot cards, the reader used Lenormand cards, named after Madame Lenormand, a famous nineteenth century French fortune teller. (Some sources claim that Lenormand adapted the deck from a pre-existing parlor game, the “Game of Hope”.)

I needed to distract myself from the inevitable pre-speech jitters,* so I sat down, prepared to be intrigued by tarot cards yet again. To my surprise, I was treated to a history lesson along with my card reading. Instead of using tarot cards, the reader used Lenormand cards, named after Madame Lenormand, a famous nineteenth century French fortune teller. (Some sources claim that Lenormand adapted the deck from a pre-existing parlor game, the “Game of Hope”.)

We don’t know much about Lenormand’s early life–her biographies are inconsistent and have the whiff of mythology. She is generally believed to come from Normandy–le normand. What we do know is that Marie Anne Adelaide Lenormand (1772-1843) rose to fame during the Napoleonic era, reading the cards of notable figures who passed through Paris. According to one account, she once read Napoleon’s cards. Instead of telling him what he wanted to hear, she informed him that according to the cards he would ultimately be unsuccessful in his military conquests–a piece of fortune-telling integrity that landed her in jail for a time.

Lenormand successfully plied her trade in Paris for forty years, making enough good predictions for influential people to earn both a reputation and a small fortune.

As far as my reading went, that’s between me, the card reader and the cards.

*Those jitters are crucial. They seem to be tied to the energy that makes the speech come alive. But they aren’t comfortable.