Pamela D. Toler's Blog, page 4

July 31, 2025

Rebecca Harding Davis: Making Things Real

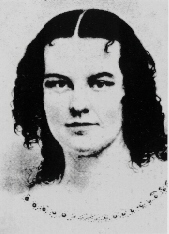

Rebecca Harding Davis, ca 1865

One of the joys of writing this blog is that when things are going well one post leads to another idea, another story, another question. It feels like my list of possible topics bubbles and fizzes* and I can hardly decide which story to tell you next.** This is one of the times when the ideas are flowing.

Which brings me to Rebecca Harding Davis (1831-1910) , with a hat tip to Helena Luna who (very politely) pointed out on Bluesky that I had barely scratched the surface of Davis’s story when I mentioned her in my post on her son ,Richard Harding Davis. I scuttled off to find out more.

Rebecca Harding grew up in Wheeling, Virginia,*** which was then a booming factory town, with an economy based on iron and steel mills. Originally home-schooled by her parents, she went away to boarding school at fourteen. After graduating at the top of her class, she returned home to Wheeling, where she joined the staff of the local newspaper.

Back home, she began to write stories and publish them anonymously. (Not an unusual choice for women writers at the time.) She became famous in literary circles with the publication of her novella, Life in the Iron Mills, which appeared in The Atlantic Monthly in April 1861.**** The novella impressed contemporary readers with its detailed and dark depictions of the conditions under which mine workers and their families existed. A few months later, The Atlantic Monthly began publishing Margret Howth: A Story of To-Day, her novel about a young woman working in the mills to support her family, as a serial. (It was later published in book form.) At much the same time, she also began publishing in Peterson’s Magazine, a women’s magazine that was less prestigious than The Atlantic, but paid its authors more. (Don’t get me started.)

In June, 1862, Rebecca traveled to Boston to meet the editor of The Atlantic Monthly. While there she met several prominent New England authors, both those who had praised her work as a brave new voice and those whose work she had long admired. (I picture mutual fan-girl squealing when she met Louisa May Alcott.) From there she went on to Baltimore, New York, and Philadelphia. In Philadelphia she met journalist Lemuel Clarke Davis, who had sent her a fan letter praising Life in the Iron-Mills. They had corresponded during the months that followed. A week after they met In Real Life, they became engaged. (Do not underestimate the power of correspondence as courtship.) They married a year later and settled in Philadelphia.

For several years, while Lemuel established himself in his career, Rebecca was the primary breadwinner of the family. In addition to writing for Peterson’s Magazine, she contributed stories and articles for national magazines like Harper’s New Monthly, Putnam’s Magazine, Saturday Evening Post, and Scribner’s Monthly, as well as children’s magazines like Youth Companion. She published six more novels and an autobiography, which were well received at the time but largely forgotten today, except in the academic circles that study forgotten women writers. In 1869, she became a regular contributor to and editor of the New York Tribune, where she remained for almost twenty years.

She published more than 500 works over the course of her lifetime. ( A number that makes me tired just thinking about it.) But she was almost forgotten at the time of her death in 1910. She was rediscovered in 1972 when feminist author Tillie Olsen republished Life in the Iron Mills in the Feminist Press.

Today Rebecca Harding Davis is considered a pioneer of literary realism in American literature.

*Or maybe I’m the one bubbling and fizzing. It’s always exciting when the work flows. Sometimes I actually have to stand up and walk away from the computer because I get so excited that I can’t keep up. (Yes, I am a nerd. Your point?)

**As opposed to the days when I look at the list of ideas for blog posts and wonder why I thought any of them were worth writing about. I’ve learned to walk away from that feeling as well, because while some of the ideas in fact turn out to be duds, the real problem in that moment is me. (Apparently the answer is always to get up and walk away.)

***Now West Virginia—a fact which led me down a little rabbit hole. Short version: Many people in the area that is now West Virginia had wanted to secede from Virginia since 1829 for what boils down to insufficient representation in the state legislature , over-taxation, and not enough state funds coming back into the region. When Virginia voted to secede from the United States in 1861, western leaders chose not to follow the state’s lead and remained loyal to the Union. In other words, they seceded from the secession.

****The same month the American Civil War began, and shortly before West Virginia became West Virginia.

July 28, 2025

Corsets for Victory?

And speaking of lady’s undergarments, as I believe we were, I can’t resist sharing this tidbit:

When America entered World War I in 1917, chairman of the War Industries board Bernard Baruch asked women to stop buying corsets to conserve steel, part of the wider program of rationing, conserving and allocating materials important to the war effort. Thanks to the cooperation of patriotic women, some 28,000 tons of steel was diverted from corset manufacturers to wartime industry. Enough to build two battleships.

Some things you can’t make up.

July 25, 2025

Ida Rosenthal: Dressmaker Turned Underwear Tycoon

As I mentioned recently, I’ve been thinking about women entrepreneurs and their stories in an on-again off-again way for the last few months. As I stumble across them, I’ll share them with you. Because that’s what I do.

Next up, Ida Rosenthal (1886-1973), whom I mentioned in passing several posts ago.

I first stumbled across Ida Rosenthal in 2012 when I was working on Mankind, the Story of All of Us.* I was writing a sidebar titled “The Other Makers of the Modern World” for a chapter that looked at America’s second industrial revolution and how it transformed the world. I was determined to get a woman in the list. (See note below.) Rosenthal, who invented the modern bra in partnership with her husband, seemed like a perfect choice.

I wrote my three sentences about her, and then I rushed on to the next thing because my deadline for the book was short and the process was, to put it mildly, chaotic. I stumbled across her now and then, but I didn’t have women entrepreneurs on my mind and had other stories to tell you here.

In 1905, a young Jewish woman named Ida Kaganovich immigrated to the United States, following her future husband, a sculptor named William Rosenthal. She believed in socialism and women’s rights. She also was determined to work for herself rather than others. Having apprenticed as a seamstress before she left Russia, she bought a Singer sewing machine** on the installment plan and went into business as a dressmaker, first in Hoboken, New Jersey, and later in Manhattan.

In 1921, Ida was presented with a new opportunity. A woman named Enid Bisett owned a dress shop in mid-town Manhattan, Enid Frocks. One day a customer came in wearing a dress that was new to Enid. When Enid asked about it, she learned it was the creation of a dressmaker named Ida Rosenthal. She made contact with Ida, hoping Ida would supply the shop with some of her dresses. The more they talked, the bigger the possibilities seemed. Instead of using Ida as a suppler, Enid suggested a business partnership.

Soon the partnership expanded. When the Flapper look came into style, many women had to wrap their chests, often in a “bandeau bra,” to achieve the fashionable flat-chested “boyish form.” Ida, not built on the flapper model herself, did not like the idea. “Why fight nature?” she asked. Inspired by Ida’s objections, Enid and William created built-in bandeaux with cups that supported and separated the breasts, making more buxom women took better in their flapper dresses. Customers loved the new dresses, but they loved the new support even more. Return customers asked if they could buy the support without the dress.

By 1922, the partners had registered the name Maiden Form. At first they included one extra support with each dress sold. By 1925, at Ida’s insistence, the partners stopped dressmaking so they could focus on their hot new product. They sold 500,000 bras in 1928. By the end of the 1930s, Maiden Form products were sold in department stories around the world.

Ida was the management and marketing genius; William was the designer. (A division of labor we’ve seen before. ) William died in 1958. Ida continued working until she suffered a stroke in 1966. At her death in 1973, she left behind a multi-million dollar business.

*A companion book for the History Channel series of the same name. And yes, I realize there is inherent sexism in the title, but it was set in stone before I joined the project. Over the years, I’ve tried to think of a better title with no success. Especially since the story as the History Channel wanted it told was very male-centric.

**Isaac Singer ‘s sewing machine was the first widely available home appliance. Commercial sewing machines already existed, but not only improved the machine but mass-produced themfor the home market.

July 21, 2025

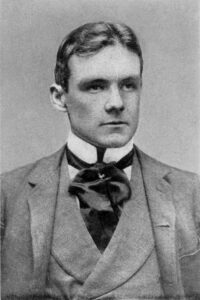

Richard Harding Davis: Journalist-Adventurer

I first ran across Richard Harding Davis (1864-1916) when I was doing research on American foreign correspondents as part of the background for The Dragon from Chicago. He looked like a fascinating character, but he was a generation (or maybe even two generations) earlier than Sigrid Schultz, so I gave him a nod and went on my way. When he recently crossed my path again (1) I decided to give him a closer look.

Davis is best known today as a war correspondent, but in his time he was also famous as a novelist, dramatist, adventurer, and man about town. At one point, he had three plays running on Broadway at the same time. His novels were best sellers. (At least one of them is still in print.) Moreover, several of his books were turned into movies. Much later, one was the basis for a short series on the Wonderful World of Disney. (2) He partied with the Gilded Age’s literary and theatrical elite, and was often the subject of the news as well a reporter of the same. H.L. Mencken, who was known for his caustic wit not for fanboy flattery, once described him as “the hero of our dreams. ” In short, Davis was a Celebrity.

Born in Philadelphia during the American Civil War, Davis came from writing people. His father was the editor of the Philadelphia Public Ledger and his mother, Rebecca Harding Davis, was a well known novelist and journalist in her own right. (3)

After attending Lehigh University and Johns Hopkins without completing a degree, Davis entered the newspaper business, with a little help from his father. He worked as a reporter for The Philadelphia Record for three months before he was fired for incompetence. (Davis claimed his editor didn’t like him because he wore gloves on cold days. ) He went on to work for two other Philadelphia papers, The Philadelphia Press and The Philadelphia Telegraph. While at The Press, he went undercover at a saloon where criminals were known to hang out. There he gained the confidence of a gang of burglars who were terrorizing the saloon and was instrumental in their capture—an adventure that allowed him to write about burglary from the inside. (4)

From Philadelphia, Davis moved to New York, where worked first as a reporter for The Evening Sun and later as the managing editor for the illustrated magazine Harper’s Weekly.

After three years at Harper’s Weekly, he left to devote himself to his own writing. He published several popular travel books based on his experiences as a roving reporter for a variety of publications. His travels also provided the raw material for his fiction, which generally centered on a “gentleman-adventurer” who bore a resemblance to Davis himself.

In 1896, Davis added war correspondent to the mix, when William Randolph Hearst, owner and editor of the New York Journal, who went on to build the Hearst media empire, commissioned Davis to cover the Cuban rebellion against Spanish rule. (5) Davis’s stories from Cuba helped created a new American interest in the rebellion.

He went on to report on the Greco-Turkish war of 1897, the Spanish -American War (1898) (6) the Second Boer War (1899-1902) , the Russo-Japanese War (1905), the Balkan Wars (1912-1913), the attempted revolution in Venezuela (1902), and what was then called the Mexican Punitive Expedition (1916) . His war reporting in this period was much like his travel writing, with a swashbuckling style, vivid metaphors, and a romantic vision of war. He often worked in isolated locations, and placed himself in the middle of an adventure. (Even though he lived in a tent and wrote on a typewriter perched on a cracker box, he didn’t exactly rough it. It took several pack animals, and a servant or two, to carry the kit he took into war zones, which included luxuries like a folding bathtub. (7)

By the time World War I began, in late July, 1914, Davis was the best-known and best-paid reporter in the United States. It was a foregone conclusion that he would head to Europe to report on the Great War.

On August 5, 1914, Davis and fellow correspondent Frederick Palmer,—who was also an experienced war correspondent, though in a less heroic mold—sailed for Europe on the Lusitania, with the expectation of receiving credentials from either the British or the French government that would allow them to travel with their armies and file reports on the war from the front. When they arrived, they discovered that Britain, French and Belgium not only refused to issue war correspondent credentials to foreign reporters, but they banned reporters from the war zone. Davis and Palmer ignored the restrictions and made their way to Brussels, armed with U.S. passports and letters from their editors, and prepared to take their chances with the dangers of operating outside the system.

Living in a hotel in Brussels, rather than camping near the front, was a new experience for Davis. So was the war itself. It was not an adventure. It was not romantic. He laid out the difference in a powerful piece he wrote for Scribner’s Magazine after the Germans marched into Brussels:

“As a correspondent I have seen all the great armies and the military processions at the coronations in Russia, England, and Spain, and in our own inaugural parades down Pennsylvania Avenue, but those armies and processions were made up of men. This [the German army] was a machine, endless, tireless, with the delicate organization of a watch and the brute power of a steam roller. And for three days and three nights through Brussels it roared and rumbled, a cataract of molten lead…like a river of steel… a monstrous engine.”

After the Germans took Brussels, Davis learned that the Germans were no more willing to give credentials to reporters than the combatant powers on the other side.

Davis attempted to get closer to the front. (In a taxi!) He had a pass from the German military governor of Brussels that allowed him to travel around Brussels; he hoped it would allow him to travel through the German lines. It did not. He was arrested as a spy and threatened with execution. He talked his way out of danger by promising to walk back to Brussels and check-in with every German officer along the way.

Later, having made his way to the front on the British and French side, he was arrested by the French army as he traveled from Reims to Paris. He used both arrests as fodder for the type of stories for which he was famous, but the war was wearing him down.

In the fall of 1915, Davis left France for the Balkans, at the beginning of the German advance into Serbia. He arrived in Salonika in November, just in time to report on the French retreat from Serbia, only two weeks after they arrived. Together with British photographer James Hare, Davis traveled into Serbia to report on the last Allied fighters there. They found a small British artillery unit commanded by two teenaged British officers, who were dug into a Serbian hillside, protecting the rear of the retreating army. Davis’s story on the unit, “The Deserted Command,” was heroic and heartbreaking.

Davis’s last and most famous story was written after an encounter in Salonika with an American who had volunteered as a medic in the British army. “Billy Hamlin,” the pseudonym Davis gave him, was tired, bitter, disillusioned, and ready to desert. Four war correspondents who had gathered for a drink in a hotel room talked him into going back. “The Man Who Knew Everything” was a new type of story for Davis. It was gritty and realistic, unlike the romantic heroism of his earlier work, and in many ways was a criticism of the heroic brand of war correspondent that he himself had embodied.

It is possible that Davis would have gone on to make a leap to the modern style of war reporting that was taking shape in the hands of younger journalists like John Reed (1887-1920) (8) But he never got the chance. Declaring to a friend that “By gravy, this war is my Waterloo. I’m going home,” he headed back to New York. He died there a few weeks later, at the age of 52.

“The Man Who Knew Everything” ran in the September 1916 issue of Metropolitan Magazine, five months after Davis’s death.

(1) Charles Dana Gibson used Davis as the model for the dashing young men who danced, bicycled, and otherwise frolicked with his eponymous Gibson Girls. (As opposed to the short, balding older men who tried unsuccessfully to flirt with the gorgeous young women.) He—Davis, though I suppose you could make the same claim about Gibson— is credited with making the clean-shaven look popular among young men. Perhaps a reaction to the epic beards sported by many Civil War veterans in the second half of the nineteenth century?

(2) “The Adventures of Gallagher,” the story of a newspaper copy boy with aspirations of becoming a reporter who solves crimes in the Wild West. I remember it mainly as a source of frustration because we always seemed to catch an episode in the middle of the story, which meant I never knew how it started or ended. Grrr.

(3) I originally mistyped that as “write” and was tempted to let it stand.

(4) This was the period when “stunt journalism” was big. Think Nellie Bly (1864-1922), who became famous for going undercover to expose corruption and injustice. Her book Ten Days in a Mad-House documented the horrific conditions she observed when she posed as a mental patient in a New York asylum. But I digress.

(5) Hearst also commissioned noted artist Frederick Remington to illustrate Davis’s articles. It was a golden age of illustration, as well as “yellow journalism.” In a probably apocryphal exchange, Remington is alleged to have cabled Hearst “Everything is quiet here. There is no trouble here. There will be no war. I wish to return.” Hearst’s (also alleged) response: “Please remain. You furnish the pictures, and I’ll furnish the war.” It is an engaging story that first appeared in 1901 and gained traction in the 1930s when distrust of the Hearst media was on the rise. It has became a standard element of histories of the Spanish-American war and Hearst biographies ever since, but it appears to have no more truth than Marie Antoinette’s thoroughly debunked extortion to “Let them eat cake!” Once again, I digress.

(6) In which he hobnobbed with Teddy Roosevelt and the Rough Riders, and helped create the legend surrounding them. In some accounts, he charged up San Juan Hill alongside them. In others, Roosevelt made him an honorary member of the regiment in thanks for rescuing some of its members who were wounded. Maybe. Maybe not. If nothing else, my guess is that Davis’s stories of sitting around the campfire with Teddy and the boys, drinking and telling stories, is probably true.

(7) His kit , which he discussed at length in Notes From a War Correspondent (1905), became part of his persona as a journalist-adventurer

(8) Best known for his work on the Russian Revolution, Reed was a journalist-adventurer in his own right.

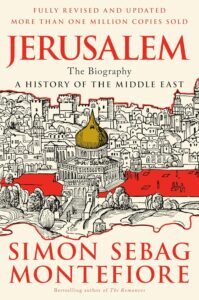

July 18, 2025

From the Archives: Slouching Toward Jerusalem

I really meant to have a brand new blog post for you all today, but the one I was working expanded in all directions (six asterisked footnotes at last count) and finally turned into a tangled mess. The footnotes are currently the only readable part. Rather than leaving you without a Friday post, I’m sharing this one from July 2011, when History in the Margins was only two months old and I wasn’t sure I could find enough to write about. Now, if you’ll excuse me, I have a story to untangle.

I’ve been fascinated by the Crusades for several years now. Not surprising, I suppose, given my basic interest in the times and places where two cultures touch (or in the case of the Crusades, whack at) each other and change. I’ve read accounts of what the Crusades looked like from the Muslim perspective. (Barbarian invaders who didn’t take enough baths). I’ve been fascinated by the changes in Europe that made the Crusades possible. (Do not underestimate the impact of the steel-tipped heavy plow and the horse yoke.) I’ve spent a lot of time on the innovations the Crusaders brought to Europe. (Don’t get me started.) I even toured a Crusader castle in Turkey with My Own True Love, who’s pretty fascinated by the Crusades himself.

But until recently I hadn’t given much though to the place that stands at the very heart of the Crusades: Jerusalem. I “knew”, in a fuzzy general knowledge sort of way, that Jerusalem was a sacred city for Judaism, Christianity and Islam. That was enough.

Until, of course, it wasn’t.

When a recent assignment forced me to think about Jerusalem in a more detailed way, I wasn’t sure whether I wanted to start with Karen Armstrong’s Jerusalem: One City, Three Faiths or Simon Sebag Montefiore’s Jerusalem, the Biography. I choose history over theology pretty much every time. But Montefiore’s book, which traces the history of Jerusalem from the time of David through the Six-Day War, looked like a dense concrete block.

I flipped a coin. History prevailed. (Here’s where I need to say something like “don’t judge a book by its cover”, or at least not by how many pages it has.)

Jerusalem, the Biography may be long, but it’s also fast-paced and smart. Montefiore’s stated goal is “to show that Jerusalem was a city of continuity and coexistence, a hybrid metropolis of hybrid buildings and hybrid people who defy the narrow categorizations that belong in the separate religious legends and nationalist narratives of later times.” He more than succeeds. Montefiore weaves together stories I thought I knew into a larger framework that illuminates them in ways I didn’t expect. Over and over I enjoyed a flutter of recognition, followed by “wow, I didn’t know that”. The book is full of vivid characters: familiar, unfamiliar, and unexpected. (I had no clue that Cleopatra had anything to do with Jerusalem. Did you?)

Montefiore is also is a master of the miscellaneous tidbit. For example: the emperor Vespasian introduced public lavatories to Rome. Today, public lavatories are still known as vespasianos. I don’t know about you, but I find this kind of stuff irresistible.

Between big revelations and fascination tidbits, my library copy was stuffed with Post-it notes by the time I reached the end of the book.

Plenty of intellectual roads lead to Jerusalem. If you’re slouching, marching or just moseying along on any of them, Jerusalem, the Biography would make a good travel guide. But don’t say I didn’t warn you. You’re going to want your own copy–or a lot of Post-its.

July 15, 2025

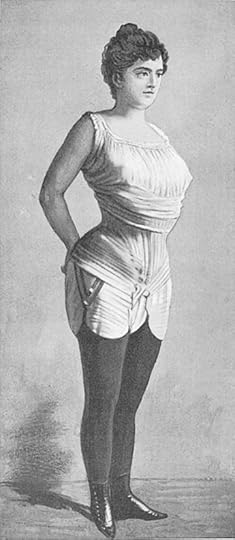

The Secret Behind the Gibson Girl’s Shape

The Gibson Girl, as I previously mentioned, had a distinctive silhouette: a small waist, an ample bosom, and a graceful sway to her back that thrust the aforementioned bosom forward and the bum backward. In some ways she was similar in shape to a Barbie doll, and, like Barbie, her figure was difficult for the average woman to attain.

The secret was the swan-bill corset, sometimes called the S-bend corset. And in keeping with the Gibson Girl’s reputation as an active, modern woman, the swan-bill corset was designed as a healthier alternative to the previously popular v-shaped corsets, which created a tiny waist in contrast to rounded hips, bust and belly and which had dominated women’s fashion in one form or another for several decades.

Healthier corsets were not a new idea. Doctors and dress reformers regularly railed against the fashion of tight-lacing to create an artificially small waist. Health corsets were intended to be comfortable while still supporting the bust.* They were often made with lighter-weight fabrics, elastic instead of bone or metal, buttons instead of a rigid steel busk at the front of the corset,** and more gentle shaping. For the most part, health corsets created a less dramatic version of the popular silhouette but did not change it.

Dr. Inès Gaches-Sarraute (1853-1928) invented the swan-bill corset in the 1890s, at much the same time as the Gibson Girl herself caught the public imagination. As a doctor, she saw women with gynecological issues and other medical problems that she believed were caused by the inward curve at the waist of the v-shaped corsets, which put pressure on the diaphragm, the abdomen and “vital female organs.”. The long, straight front of the swan-bill corset was intended to support the abdomen rather than constrict it.

Gauches-Sarraute did not intended her version of the health corset as a fashion statement. She billed it as a medical device. But unlike earlier health corsets, the swan-bill corset produced a new silhouette that inspired fashion designers to create a new style of clothing and their customers to adopt a changed posture borrowed from the military parade ground.***

*Although a few enterprising corsetiers, and one ingenious society woman, had created earlier versions of the bra, they did not take off until dressmaker Ida Rosenthal and her sculptor husband created the first commercial bra in the 1920s in response to the new shape demanded by flapper look. A story for another day.

*** The two-part busk itself was an improvement that made it easier to put a corset on and off without help.

***At least while posing for pictures. Many women achieved the new shape with discreet padding for and aft rather than by hyper-extending their back.

July 10, 2025

From the Archives: A Word with a Past: Kidnap

In the mid-seventeenth century, the British colonies in North America and the Caribbean were suffering from a labor shortage.

The colonies had originally attracted Britain’s surplus population: dreamers, fortune-hunters, religious nuts, younger sons, prisoners of war, political failures, vagrants, criminals, the homeless, and the desperate. Some came with a small financial stake. Many came as indentured servants. A few were physically coerced onto ships sailing west.*

In 1640s and 1650s, the population base in Britain took a hit. More than eleven per cent of the population died in the English Civil War. (In World War I, Britain’s second most devastating war, the loss was only three percent.) With so many young men killed, the birth rate went down. Consequently, wages went up. Plenty of people must have asked themselves, “Why leave civilization for the colonies?”

With voluntary immigration down, involuntary immigration became more important. The inmates of Britain’s prisons were given a chance at a new life–whether they wanted it or not. Grown men were “Barbadosed”–the seventeenth century equivalent of being shanghaied. (Another word with a past–and ugly imperialist/racist roots–now that I think about it).

Worst of all, children were snatched from their parents and sent to the colonies as indentured servants. As a result, a new word entered English:

Kidnap. .vt. To steal or carry off children or others in order to provide servants or laborers for the American plantations.

*Re-reading this fourteen years** after I originally wrote the post, I realized I slid right past the fact that thousands of Africans were being enslaved and sent to the New World at the same time. Perhaps I notice it now because I’ve been working hard at recognizing my historical blinders.

**Time passes when you’re reading and writing about history.

July 8, 2025

Charles Dana Gibson and the Great War

Seven days after the United States entered the Great War in April 1917, Woodrow Wilson established the Committee on Public information, a semi-official propaganda agency headed by journalist George Creel. The goal of the committee was to use mass communication to build support for the war effort.

While much of the committee’s work was aimed at placing articles in newspapers and magazines, Creel understood the power of visual arts. He later wrote:

“Even in the rush of the first days … I had the conviction that the poster must play a great role in the fight for public opinion. The printed word might not be read; people might choose not to attend meetings or to watch motion pictures, but the billboard was something that caught even the most indifferent eye …. What we wanted—what we had to have—was posters that represented the best work of the best artists—posters into which the masters of the pen and brush had poured heart and soul as well as genius.”

Creel appointed Charles Dana Gibson, then president of the Society of Illustrators and one of the best known and highest paid artists in the country, as the head of the Division of Pictorial Publicity. Gibson recruited more the 300 of the country’s top illustrators as unpaid volunteers, urging them to “Draw ’til it hurts.”* Over the course of two years, the division created more than 1400 pieces, including 700 posters for 58 government departments, exhorting Americans to enlist, buy liberty bonds, collect books for soldiers, and avoid waste.

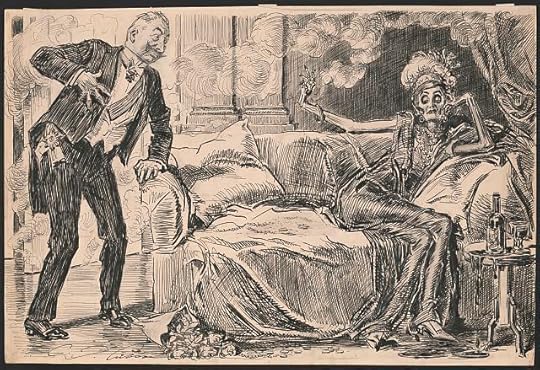

In addition to leading the Division of Pictorial Publicity, Gibson also created satirical ant-German political cartoons for Life magazine. One of the most powerful was “And the Fool, He Called her His Lady Fair,”** which was published on May 7, 1917, only weeks after the United States entered the war. In it, Gibson presents war as a skeletal woman being wooed by a male figure who bears a clear resemblance to Kaiser Wilhelm II. Wreathed with cigarette smoke, dripping with jewels, wine dripping in blood-like puddles at her feet, she is long way from the wholesome Gibson Girl.

*Gibson also selected eight artists to travel with the American Expeditionary Force and record scenes from the front lines. The eight, who all were successful commercial illustrators for major magazines. were commissioned as captains in the Army. It was same rank given to accredited war correspondents, and in fact their work can been seen as another type of war reporting. If you want to know more about their story, you can read an article I wrote about it here. But I digress.

**A line from Rudyard Kipling’s poem “The Vampire.”

July 3, 2025

“When in the course of human events”–you know how it goes from here

Here in the United States, we are celebrating the 4th of July.

It’s a hot day in Chicago, where I live. The city is hosting a NASCAR race and Mensa’s Annual Gathering—two events that may never have been in such close proximity before. There will be official fireworks in suburbs throughout the area, though none in Chicago itself, and unofficial fireworks in the park across the street from my house and the alley behind it. (Well into the early hours. Ms. Whiskey and I will not be happy.) The city’s parks are full of families setting up canopies, lawn chairs, folding tables loaded with food, and charcoal grills.

Personally, I plan to attend my neighborhoods’ “everyone marches” parade.

I also plan to take a few moments to think about why we are celebrating. The promise that has not yet been completely fulfilled but which stands at the core of who we are as a nation:

We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.

It is a promise worth remember, and worth fighting for.

June 30, 2025

Charles Dana Gibson and the Gibson Girl

Charles Dana Gibson (1867-1944) was an important illustrator in the Golden Age of American illustration. He sold his first illustration in 1886 to Life magazine,* where his works appeared every week for thirty years. Soon his drawings appeared in every major American magazine, including Harpers’ Weekly, Scribners and Colliers. He illustrated books, including American editions of Charles Dickens’ novels, The Prisoner of Zenda, and Gallegher and Other Stories by swashbuckling journalists and adventurer Richard Harding Davis.** in 1918, he became first editor and then majority owner of Life.

But his most important impact on American culture was the “Gibson Girl,” whose distinctive silhouette and pompadour hairdo became the ideal for American beauty from the 1890s into the 20th century. (I was amused to see that his Princess Flavia, in The Prisoner of Zenda, had an air of the Gibson Girl about her. Evidently the ideal reigned in Ruritania as well as the United States.)

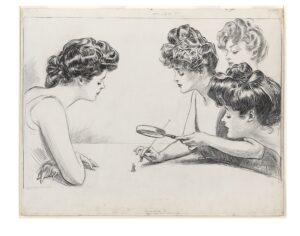

The Gibson Girl was tall, aloof, stylish, and above all, modern. She was equally at home at balls, on bicycles, and at the beach.*** There is often a satirical, feminist element to the images, most notably the drawing titled “The weaker sex” in which Gibson Girls examine a tiny male figure with a magnifying glass, one of them preparing to poke him with a hat pin as if he were an entomological specimen for collection.

(The feminist element can possibly be attributed to the fact that his wife, Irene Langhorne Gibson, who was one of his models and believed to be the original model for the Gibson Girl, was an active suffragist and progressive activist.)

The Gibson Girl was edged off the page as a beauty icon during World War I, when women’s roles, and fashions, began to change in fundamental ways.

*Founded in 1883, Life was originally a general interest and humor magazine, which featured illustrations from many prominent artists of the time. In 1936, magazine mogul Henry Luce purchased the magazine and took advantage of new printing technology to relaunch it as the iconic photographic news magazine, giving Life a new life as it were. (Sorry. Sometimes I can’t help myself.)

**Who deserves to be the subject of a blog post in his own right, now that I think about it.

*** Her image also appeared on a variety of merchandise, including dishes, pillows, wallpaper, and even shirtwaists. (The idea of wearing a shirtwaist with a picture of a shirtwaist wearing Gibson Girl has a meta quality that amuses me,)