Pamela D. Toler's Blog, page 34

January 17, 2023

From the Archives: Pippi Longstocking Goes to War

(Okay, I admit it. That’s an inaccurate, click-bait of a title.)

In every book I write I reach the point where I am so deep in the work that I have to stop writing blog posts and newsletters. I always hope to avoid it. That somehow I’ll be smarter, or faster, or more organized, or just more. This time I’ve managed to avoid hitting the wall for several months by cutting back to one post a month. But the time has come. For the next little while, I’m going to share blog posts from the past, starting with this one from 2019. I hope you enjoy an old favorite, or read a post that you missed when it first came out.

There will be new posts in March no matter what: we celebrate Women’s History Month hard here on the Margins.

Today Astrid Lindgren is famous as the creator of Pippi Longstocking: the red-headed quirky rebel who proclaimed herself the strongest girl in the world.* In World War II, Lindgren was a 30-something housewife and aspiring author. Her war diaries, published posthumously in Sweden and recently translated into English, are a fascinating account of life in neutral Sweden during World War II.

If you read War Diaries, 1939-1945 hoping to get insight into the creative process behind Pippi Longstocking, which was published just before the end of the war. you will be disappointed. There are few references to her writing. If you want a wartime narrative written by an intelligent observer that offers a different perspective than the British accounts most familiar to American readers, Lindgren’s your girl.

The diaries are a mixture of the personal and political. Marital problems, concerns about her son’s difficulties at school and rumors about increased rationing are intermixed with her determination to document the course of the war. She lists the menus for birthday dinners and holiday celebrations, commenting each time on how lucky Sweden is to have abundant food and fearing that each feast will be the last. She pastes in newspaper clippings of critical events.

She also adds privileged information that adds depth to her reporting. Lindgren worked on the night shift for a government security agency responsible for censoring correspondence sent from or to other countries. Although her work was so hush-hush that her children did not know what she did, she had no hesitation about copying and commenting on sections of the letters in her diaries, including letters describing the transportation of Jews to concentration camps in Poland as early as 1941.

Lindgren’s War Diaries tell the story of the war as seen through the veil of Swedish neutrality—a veil that Lindgren recognized was perilously thin. She records her relief and guilt over Sweden’s relative prosperity, her shame over allowing German troops to travel through Sweden, and her fear that Russia will prove to be a greater threat to Sweden than Germany. For those of you who are serious World War II buffs, it may all be alte wurst. For me, it was a new approach to a familiar topic.**

*One of a long string of red-haired literary rebels and misfits who inspired and comforted a certain red-haired history buff as a child.

**I’m beginning to see a theme here. Sometimes I think I know nothing at all about history.

January 12, 2023

From the Archives: A Woman’s Home is Her Castle

In every book I write I reach the point where I am so deep in the work that I have to stop writing blog posts and newsletters. I always hope to avoid it. That somehow I’ll be smarter, or faster, or more organized, or just more. This time I’ve managed to avoid hitting the wall for several months by cutting back to one post a month. But the time has come. For the next little while, I’m going to share blog posts from the past, starting with this one from 2019. I hope you enjoy an old favorite, or read a post that you missed when it first came out.

There will be new posts in March no matter what: we celebrate Women’s History Month hard here on the Margins.

* * *

As I believe I’ve mentioned before, in Treasure of the City of Ladies; or the Book of the Three Virtues, author, intellectual, and champion of female education Christine de Pizan (1364–1430) instructed noblewomen of her time to learn the military skills they needed to defend their property: “She ought to have the heart of a man, that is, she ought to know how to use weapons and be familiar with everything that pertains to them, so that she may be ready to command her men if the need arises. She should know how to launch an attack, or defend against one.” It was good advice. Noblewomen and queens often found themselves leading the defense of a keep, castle, or manor (and occasionally besieging someone else)—even if they didn’t have “the heart of a man.” (1) (Occasionally, not-so-noble women also found themselves under siege. Margaret Paston (1423–1484), the wife of a wealthy landowner and merchant, defended besieged properties three times against noblemen’s attempts to seize them by force.)

As I believe I’ve mentioned before, in Treasure of the City of Ladies; or the Book of the Three Virtues, author, intellectual, and champion of female education Christine de Pizan (1364–1430) instructed noblewomen of her time to learn the military skills they needed to defend their property: “She ought to have the heart of a man, that is, she ought to know how to use weapons and be familiar with everything that pertains to them, so that she may be ready to command her men if the need arises. She should know how to launch an attack, or defend against one.” It was good advice. Noblewomen and queens often found themselves leading the defense of a keep, castle, or manor (and occasionally besieging someone else)—even if they didn’t have “the heart of a man.” (1) (Occasionally, not-so-noble women also found themselves under siege. Margaret Paston (1423–1484), the wife of a wealthy landowner and merchant, defended besieged properties three times against noblemen’s attempts to seize them by force.)

The skills needed to withstand a siege were an extension of housekeeping when the idea that a man’s home was his castle was a literal description for members of the aristocracy. In medieval and early modern Europe, noblewomen were often responsible for managing family properties, and consequently for providing the military resources needed for those properties. Provisioning a household that was as much an armed fortress as a family domicile involved procuring the cannons, small arms, and gunpowder needed for its defense as well as the day-to-day supplies of food, clothing, or household linens. Noblewomen supervised men-at-arms in the course of daily life and helped mobilize the household’s resources for war. Leading its defense was one more step down a familiar road.

We find stories of women organizing the defense of a besieged castle/keep/manor in sixth century China, in the dynastic wars of medieval Europe, in the religious wars of seventeenth century England and France and in shogunate Japan. (2) Some led their men-at-arms into battle, weapons in hand. Most harangued the enemy and encouraged their troops. (Sometimes they also harangued their men-at-arms. In 1584, the wife of samurai warrior Okamura Sukie’mon armed herself with a naginata, (3) patrolled the besieged castle, and put the fear of the gods in any soldiers she found asleep while on duty.) More than one noblewoman, such as Hungarian nationalist Llona Zringyi (1644–1703) walked her ramparts at twilight in full view of the enemy, giving the besieging army a metaphorical middle finger.

For the most part, these women led the defense in the absence of their fathers/husbands/brothers/sons—who were often fighting elsewhere. In the case of Nicolaa de la Haye (ca. 1150–1230), the castle she defended was her own. De la Haye inherited the offices of castellan and sheriff of Lincoln when her father died in 1169 with no male heirs. In that role, she became involved in the conflicts surrounding the absentee King Richard the Lionhearted, his brother John, and England’s barons, that resulted in the Magna Carta. (De la Haye was on Team John.) (4) As castellan, she successfully defended Lincoln Castle twice, once in 1191 and once in 1216. Her resistance during the second siege led her enemies to describe her as a “most ingenious and evil-intentioned and vigorous old woman.” I suspect she took that as a compliment.

(1) I can’t tell you how tired I got of the many variations on “the heart of a man,” “manly courage”, “as capable as a man” while writing Women Warriors .)

(2) Japanese “castles” in the twelfth century were wooden stockades—more like a fort in the American West than a medieval European keep.

(3) A traditional weapon of samurai women, the naginata is a curved blade on a staff, similar to a glaive. Samurai women also carried a long dagger in their sleeves called a kaiken, sometimes referred to as a suicide dagger.

(4) We (and by that I mean Americans) tend to assume that John was the villain of the story because the only things we learn about him is that he was forced to sign the Magna Carta, which is seen as the documentary forefather of our own Constitution and Bill of Rights. (Not to mention his appearance as a villain in the Disney film Robin Hood.) In fact, Richard wasn’t exactly a stellar king from the British perspective. He was more interested in crusading in the Holy Lands than in ruling. During the ten years of his reign as King of England, Duke of Normandy and Count of Anjou, (5) he spent no more than six months in England, and is reported to have said that he’d sell the place if he could find a buyer. Not a model king by any standard.

(5) Which began with him conspiring with his mother (Eleanor of Aquitaine) and the king of France to seize the throne from his father . (Not for the first time. He had previously joined two of his brothers in an unsuccessful rebellion in 1173.) Happy family.

*****

Chicago Friends: I’m going to be “in conversation” with author Dawn Raffel at the Seminary Coop Bookstore on January 26, discussing her new book Boundless as the Sky. The book is a fascinating mixture of imaginary cities, the Century of Progress world’s fair (which in some ways was also an imaginary city), and Italo Balbo’s dramatic landing at the fair with twenty-four seaplanes. I’m looking forward to talking to her about it. Love to see you there. Here are the details: https://events.uchicago.edu/event/189868-dawn-raffel-boundless-as-the-sky-pamela-d

January 10, 2023

From the Archives: The Other Mozart

In every book I write I reach the point where I am so deep in the work that I have to stop writing blog posts and newsletters. I always hope to avoid it. That somehow I’ll be smarter, or faster, or more organized, or just more. This time I’ve managed to avoid hitting the wall for several months by cutting back to one post a month. But the time has come. For the next little while, I’m going to share blog posts from the past, starting with this one from 2019. I hope you enjoy an old favorite, or read a post that you missed when it first came out.

There will be new posts in March no matter what: we celebrate Women’s History Month hard here on the Margins.

* * *

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart is impossible to avoid if you spend any time in Salzburg. A dedicated tourist could attend a Mozart concert everyday of the week without much effort. The city has transformed both his birthplace and the building where his family rented an apartment from 1773-1787 into museums. (1) At least one tour company runs a bus tour that follows “in the footsteps of Mozart.” His picture is prominently displayed in the many, many shops that sell the ubiquitous Mozartkugel (2) and his name is attached to a number of restaurants and hotels throughout the city.

I am fond of Mozart’s music, but I came away fascinated by another Mozart, his older sister Maria Anna Walburga Ignatia Mozart (1751-1829), nicknamed “Nannerl”, who was a musical prodigy in her own right.

Maria Anna Mozart in her touring days, age 12

I had been vaguely aware of Ms. Mozart before,(3) but her story clicked into focus for me in an exhibit at the Salzburg Museum devoted to historical musical instruments. The exhibit is fascinating. Instruments from the museum’s extensive collection are not only displayed and placed in context, but recordings allow you to hear them played by professional musicians. Some are familiar, like lutes, harpsichords and French horns. Others are not: the theorbo and the pommel for instance. Personally I was fascinated by the pochette,(4) also known as the dance-master’s violin, and the steel piano, also known as steel laughter.

One of the first pieces in the exhibit was Ms. Mozart’s clavichord, and a brief description of her life. She was five years older than her famous brother, and had already proven herself a talented musician at the time that he wrote his first composition. In fact, the two toured together for three years when they were children. She sometimes received top billing and a review from that period praised her in terms not that different from those showered on her younger brother: “Imagine an eleven-year-old girl, performing the most difficult sonatas and concertos of the greatest composers, on the harpsichord or fortepiano, with precision, with incredible lightness, with impeccable taste. It was a source of wonder to many.”

But actions that were acceptable for a little girl were not acceptable for a grown woman. When Ms. Mozart was eighteen, her days on the concert trail were over. She was left behind in Salzburg when her father took her brother back on the road. She eventually married an older man chosen by her father, Johann Baptist Berchtold zu Sonnenburg. After his death, she returned to Salzburg, where she taught music.

There is evidence that she composed in addition to playing. Surviving letters (5) suggest that her brother consulted with her about musical issues. But unless new material comes to light, we’ll never know what her compositions sounded like because none of them have survived. *sigh*

(1) We visited the so-called Mozart Residence. I wouldn’t recommend it unless you are a Mozart groupie. There really isn’t much to see: the fact that one of the eight rooms is devoted to the musical career of his son who, by the museum’s own account, wasn’t anything special as a musician or composer tells you all you need to know. Much of the audio tour is snippets of Mozart’s music, which is pleasant but there are plenty of places to hear Mozart while you are in Salzburg. The best part of the museum was the final room, which talked about the use of Mozart’s image as a marketing device and included a life-size cardboard silhouette of the composer. At 5 foot and almost 2 inches, I would have towered over him.

(2) The candy—a ball of pistachio marzipan coated with a layer of nougat covered with a layer of chocolate—was created by a Salzburg confectioner in 1890. It seemed like a must try for a Salzburg visit. My take? *Meh* (Of course, I felt the same way about the Sacher torte we ordered at the Sacher hotel. I may not be the right audience for Austrian sweets.)

Mozartkugel

(3) Somehow calling her “Nannerl”, as so many scholars do, feels disrespectful and simply calling her Mozart will lead to confusion.

(4) French for pocket, because the instrument was theoretically designed to fit in a pocket. Though not in any pocket I’ve ever had.

(5) Of which there are many, thanks to Ms. Mozart herself, who served as the family’s unofficial archivist

January 5, 2023

From the Archives: Enheduanna–A Surprise from the Ancient World

In every book I write I reach the point where I am so deep in the work that I have to stop writing blog posts and newsletters. I always hope to avoid it. That somehow I’ll be smarter, or faster, or more organized, or just more. This time I’ve managed to avoid hitting the wall for several months by cutting back to one post a month. But the time has come. For the next little while, I’m going to share blog posts from the past, starting with this one from 2019.

I’ll make it up to you in March, when I’m going to run my Women’s History Month interview series no matter what.

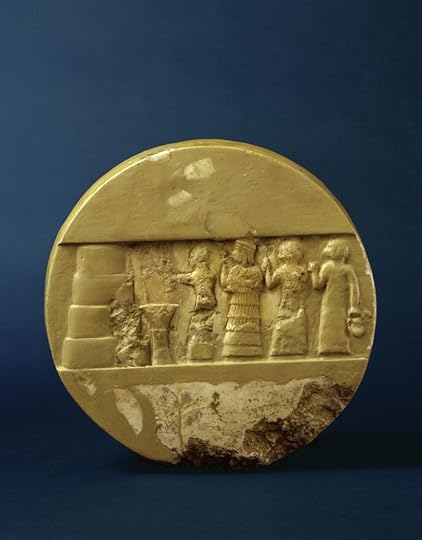

Enheduanna is the one in the middle.

Image courtesy of the University of Pennsylvania Museum, British Museum/University Museum Expedition to Ur, Iraq 1926.

Allow me to introduce you to the first author whose name is recorded in history, a WOMAN named Enheduanna (2285-2250 BCE). Enheduanna was the daughter of Sargon the Great of Akkad, ruler of Mesopotamia. Her father appointed her the high priestess of the most important temple in the Sumerian city of Ur. She may have gotten the job thanks to Daddy, but there is no doubt that she earned it. Combining her roles as both priestess and poet, she wrote more than forty liturgical works that were copied and used for almost 2000 years. In those works, she created conventions for psalms and prayers that were used throughout the ancient Middle East and Mediterranean. Her work influenced the poetic forms of the Hebrew Bible, the Homeric hymns of ancient Greece, and the early hymns of the Christian church. (That’s a lot of influence for someone I never heard of until a few days ago.) She also wrote forty-two more personal poems in which she described her feelings about the world she lived in.

She served as high priestess for forty years, despite a coup attempt that drove her temporarily into exile.

Enheduanna was rediscovered as a historic figure in 1927, during British archaeologist Sir. Leonard Wooley’s excavations of Ur. You can’t say she’s been erased from history, but she isn’t exactly a pop culture icon. (1) Yet.

(1) Except among the people who believe that aliens built the pyramids.

December 24, 2022

Another Christmas Adventure

It’s Christmas Eve and I am sitting in our hotel room in Cascais, Portugal, looking at a surprise Christmas treat the restaurant staff just delivered to our room. We have a little balcony with two comfy chairs, where it is almost warm enough to sit and stare at a gorgeous view of a gray and challenging Atlantic. We were afraid we wouldn’t get here because of the winter storms that disrupted holiday travel in the United States and we are counting our blessings.

This is the fourth time in the last ten years that we have spent Christmas in another country. Each time, I’ve learned new historical stories and widened my understanding of stories I thought I knew. I fully expect to have the same experience here. And once I’m back, I’ll share them with you.

In case you need something to keep you amused until I’m back, here are some links to earlier posts dealing with Portuguese history:

Prince Henry the So-Called Navigator

The Violent and Often Ugly Story of How Portugal Won A Global Empire

(Some of you may note that my previous knowledge of Portuguese history is very specific in scope, and you would be right.)

In the meantime, have a merry/jolly/happy/blessed time as you celebrate the victory of light over the darkness in the tradition of your choice.

December 20, 2022

The German Interplanetary Society

Over the last few few years, I’ve occasionally gotten glimpses into Sigrid Schultz’s life that don’t quite fit. The kind of things that you can picture her using in one of those ice-breaker games where you have to tell people three things about yourself, one of which is a lie. (I hate those games, but I picture Sigrid throwing herself into them with gusto.)

For example, in May, 1931, Sigrid became a member of the German Interplanetary Society (aka the German Space Club), the first society dedicated to space travel. Her membership card gave her access to the club’s rocket port: “this permission would only be withdrawn in case of particularly risky experiments.” It’s impossible to know whether Sigrid joined the organization because she had a personal interest in the subject or because she smelled a great story in the making. She certainly did not fit the profile of most members of the society, who were young male engineering and science students. (Including an eighteen-year-old student named Wernher von Braun, who joined the society in 1930. He went on to become a driving force at NASA and one of the most important rocket developers of the twentieth century.)

In 1927, a group of young Berliners formed the society, inspired by the idea of space travel. They met in an abandoned munitions depot in a Berlin suburb, which included a three-hundred acre field that they dubbed the “Rocket Airport,” where they fired miniature rockets at the moon and tested liquid-fuel rocket motors. They had little money for their expensive experiments, but they were persuasive. They talked manufacturers into giving them materials at a low cost and gave workmen free housing at the arsenal in exchange for labor.*

In the fall of 1932, news of the project reached the Weimar army, which was trying to rebuild within the confines of the Versailles Treaty. The treaty hadn’t placed any restrictions on rockets. Capt. Walter R. Dornberger, who was in charge of research and development the German army’s ordnance department recognized the military potential of liquid-fuel rockets and reached out to the Interplanetary Society.

As usual, the society desperately needed money. When Dornberger made them an offer to support their research, they did not hesitate. According to von Braun: “In 1932, the idea of war seemed to us to be an absurdity. The Nazis weren’t yet in power. We felt no moral scruples about the possible future abuse of our brainchild. We were interested solely in exploring outer space. It was simply a question with us of how the golden cow would be milked most successfully.”**

The young scientists were naive. In September 1933, Rocket Launch Site Berlin closed under the pretext of an unpaid water bill and their research was folded into the Nazi military machine. Amateur rocket tests were now against the law.

As far as Sigrid’s involvement goes, I find no article on the society or space travel in the Tribune.*** She may have just been curious. (She had hoped for a chance to ride on the first zeppelin to fly from Germany to the United States. maybe she also had dreams of being the first woman in space.)

*Not a small thing. Housing was difficult to find and expensive in Weimar Germany.

**In von Braun’s case, very successfully. The German army financed his doctoral studies in exchanged for his research.

***Pro tip: Do not search an historical newspaper archive using the word space as a keyword without limiting your search to articles. You will end up with hundreds of ad pages results. ***

****You’re welcome.

December 14, 2022

From the Archives: Road Trip Through History, Nuremberg, Pt. 2, Nazis

I have a whole list of future blog posts to share with you, but today my head is in 1933. Hitler has just become chancellor and things are getting ready to get bad fast. As part of my work on this chapter, I pulled out my notebook from our 2019 trip to Nuremberg–which feels like it happened a lifetime ago. I wanted to review my notes from Nuremberg’s amazing tough-minded museum about the rise of the Nazis. From notebook to blog post was one quick step into the past. I thought some of you might find it interesting as well.

Here we go:

One of the most impressive things about Nuremberg is the way the city looks directly at its Nazi past, and encourages visitors to do the same. Nowhere is that more evident than in two major museums: the Documentation Center-Nazi Party Rally Grounds and the Nuremberg Trial Memorial.

One of the most impressive things about Nuremberg is the way the city looks directly at its Nazi past, and encourages visitors to do the same. Nowhere is that more evident than in two major museums: the Documentation Center-Nazi Party Rally Grounds and the Nuremberg Trial Memorial.

The Documentation Center, generally called the Doku-Centrum by the locals, is built in to the single remaining major building on the Nazi Party Rally grounds: a labyrinthine concrete addition set on top of the uncompleted Congress Hall that is appropriately oppressive in style. The main exhibit, titled “Fascination and Terror” tells the story of the rise and fall of Nazi Germany from the Weimar Republic through the trials, with an emphasis on the party rallies held in Nuremberg and its symbolic role for the Nazis. (And consequently the city’s symbolic role for the trials.)

The Nuremberg Trial Memorial is located on the top floor of the Nuremberg Palace of Justice, which is a working courthouse. In fact, Courtroom 600, where the trials took place, is still a working courtroom—a fact that I found deeply moving, for reasons that I cannot articulate. (Perhaps simply because it means the room is not always open to visitors, and sitting in that room felt important.) The exhibit attempts to provide an objective account of the trial, complete with a discussion of the legal foundation for war crimes, explanations of the charges against the various men accused of war crimes, and biographies of the judges and prosecutors. (I found the amount of detail overwhelming at times, perhaps because we came directly from the Doku-Centrum.) The exhibit also looked at media coverage of the trials.

I won’t even try to give you a detailed overview of the museums, but these were a few of the things that stuck with me after the fact:

The depth of the problems in the Weimar Republic even before the Great Depression hit in 1929: political chaos as two very different groups struggled for control, an enormous public debt, monetary depreciation, attempted political assassination and armed groups in the streets. The Weimar Republic was more than cabaret and the Bauhaus.I had not realized how quickly the Nazis destroyed all the organizations and institutions that supported social pluralism or democracy. It only took a year.The Nazis deliberated used the Nuremberg’s history as a as a free imperial city and the site of the Diet in the Holy Roman Empire to support their claim that the Third Reich was completing German history. The buildings on the parade and rally grounds were designed to evoke both the Roman Empire and the Holy Roman Empire. In fact, the main road into the parade grounds pointed straight to Nuremberg’s castle, creating a visual link between the Third Reich and the Holy Roman Empire.The Nuremberg Trials did not deal with crimes against Germans by Germans. I had no idea.From the start, the allies recognized the importance of the media covering the trials. The United States Information Service created extensive support services for journalists, including offices, broadcast studios, and living accommodations. Of the 235 seats in the press gallery, seven were reserved for members of the independent German press, which was just beginning to re-establish itself after being effectively dismantled by the Nazis.Similar trials were staged in Tokyo. Again, I had no idea.My Own True Love and I visited the two museums back-to-back in one day. I’m still torn as to whether that was a good choice. On the one hand, it squeezed all the pain into a single day and left us free to concentrate on other, more enjoyable things for the rest of the trip: gingerbread, medieval trade routes and artisans, pencils, and New Year’s Eve. On the other hand, we had to rush through the end of the Nuremberg Trial Memorial. And it made for a very long, very grim day that left me with a headache and the desire to wash away the images with a long shower and a strong drink. My final judgement: it wasn’t fun but it was important to do.

_____________________________________________________

Travel Tips

1. We were lazy and took a cab, but the Doku-Centrum is easy to reach by public transportation.

2. The Doku-Centrum has a surprisingly good cafe. And a good thing, too, since it is in the middle of nothing in particular.

3. Use the audio tour. Even if you read German well, the audio tour includes layers of information that isn’t on the signs.

December 7, 2022

In which I pull another long-unread book off the To-Be-Read shelf:

There was a time when I felt guilty about the number of unread books sitting on my shelves. They come in faster than I can read them.*

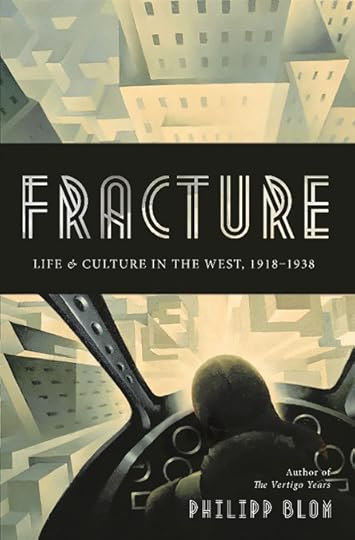

I don’t feel guilty anymore. More than once over the course of writing this book, I’ve found exactly the book I need sitting on my shelves waiting its turn. Books that I might not have known to look for out in the world. Most recently, that book was Fracture: Life and Culture in the West, 1918-1939 by German historian Philipp Blom.

Blom looks at each of the twenty-one years (which, as he reminds us in his introduction, adds up to a mere 1,567 days) from 1918 through 1938 in a separate chapter . He splits them into two parts: Postwar (1918 through 1928) and Prewar (1929 through 1938). But he does not give the reader a step-by-step narrative of the interwar years.*** Instead his structure reflects the, ahem, fractured world between the wars. He looks at

“perceptions, fears, and wishes, ways of dealing with the trauma of the war, with the energies released by industrialization, with the confusing and exhilarating identies that became possible in an industrial mass society, especially once the old values had been shattered.”

Moving from spot to spot in the Western world, he begins with jazz and works his way through the republic of Fiume, speakeasies, Charlie Chaplin, the Harlem Renaissance, the Scopes trial, Marlene Dietrich, Soviet Russia’s Five-Year Plans, and various iterations of the superman. The result is a kaleidoscopic and brilliant picture of a world that was shadowed by the war that had not quite ended and another that everyone believed was soon to come.

Fracture has become a touchstone for me as I write this book.

Who knows what I’ll find on the To-Be-Read shelves next?

*I am not attempting to downplay my responsibility here.I definitely buy books faster than I can read them. And I pick them up from the various Little Free Libraries I cross on my daily wanderings** But I also receive books from publicists for me to consider for review. (Not as often as I used to, because I don’t think it is fair to accept books for review in my current state of overwhelm.) But there is still a slow trickle. And even a slow trickle can eventually cause a flood.

**My rule in that case is that I must deposit one book for each book I take. This requires keeping track of which libraries I owe books to and which ones I am apt to pass on any given trip out the door. (Now that I think about it, I should just carry a book with me whenever I set out and donate one whether I’ve taken one or not. No record keeping involved!)

***A model I am trying to keep in mind as I struggle my way through those same years. It is all too easy to chronicle the rise of the Nazis instead of telling how Sigrid Schultz reported on the rise of the Nazis. It is a subtle difference perhaps,**** but an important one. Moreover, it is a difference that it is easy to lose track of. I write IT’S ABOUT SIGRID NOT ABOUT HITLER at the top of every Scrivener document in the draft,***** and still I wander off into the wrong story over and over.

****Or maybe not so subtle

*****I try to remember to delete it before I give a chapter to my first reader, also known as My Own True Love. He is very clear about this and doesn’t need the reminder.

November 30, 2022

Road Trip Through History: The Mother Jones Monument

Driving from Chicago to the Missouri Ozarks and back over the last mumble years,(1) I have passed the sign for the Mother Jones monument many, many times. It is a plain, almost amateurish, sign, without the official imprimatur(2) of a brown tourist attraction sign(3) or the flash of billboard advertising a show in Branson. Nothing about it is designed to lure a curious history bugg off the highway. And up to now, we have not been lured.

That changed this year, thanks to an information panel in an Illinois highway rest stop.(4) My Own True Love and I were hooked.

I had been vaguely aware that Mother Jones was a union organizer, but I had no idea how important she was at her time.

Mother Jones was in some ways the Grandma Moses of union organizers: in fact, when she was testifying before a committee in the Senate on labor issues, a senator mocked her as the “grandmother of all agitators.” (She replied that she would someday like to be called the “great-grandmother of all agitators.”) At the point that she began her career as a union organizers, Mary Harris Jones was a poor, widowed, Irish immigrant. She had had survived the potato famine, the loss of her husband an four children in a yellow fever epidemic, and the Chicago fire,which destroyed her successful dressmaking shop.

After each loss, she reinvented herself. In the 1890s, she reinvented herself one more time, as “Mother Jones.” The name was subversive: playing against and with nineteenth century domestic stereotypes of women. Mary Jones cast herself as the mother of oppressed people everywhere. At a time when women were “supposed” to be quiet and stay home,(5) Mother Jones was a street orator with no fixed address, who traveled the United States for twenty-five years, moving from cause to cause. She had no interest in being “ladylike.” As she told a group of women in New York: “Never mind in you are not lady-like, you are woman-like. God Almighty made the woman and the Rockefeller gang of thieves made the ladies.”

Jones rose to prominence as an organizer for the United Mine workers, who paid her a stipend, but she went wherever she felt she was needed. She worked with striking garment workers in Chicago, bottle washers in Milwaukee breweries, Pittsburgh steelworkers, and El Paso streetcar operators, helping them fight against 12-hour days, low wages, dangerous working conditions, and the financial servitude of company housing and the company store.

Her motto was “Pray for the dead, and fight like hell for the living”—the world would be a better place if we all adopted it as our own.

****

When we got to the monument in Mt. Olive, Illinois, we learned there is a second part to the story. Illinois became a battleground for labor rights in 1898, when the Chicago Virden Coal Company challenged the miners’ contract. They brought in a train loaded with strikebreakers and armed guards to back them Miners from across the state joined together to stand their ground against the company. In the violent encounter that became known as the Battle of Virden or the Virden Massacre, thirteen people were killed, including six guards and seven miners. Thirty miners were wounded. Mother Jones considered the battle the birthplace of rank-and-file unionism.

A Mt Olive church refused to allow the miners to be buried in their churchyard, fearing their graves would become a pilgrimage site for the labor movement. (This is what as is known as a self-fulfilling prophecy.) In response, the United Mine Workers built the Union Miners Cemetery in Mt. Olive, which in fact became a pilgrimage site after Mother Jones, at her request, was buried there in 1930. Personally, the union buttons that had been left at the foot of the monument choked me up.)

(1) And by years, I mean decades

(2)Is there such a thing as an unofficial imprimatur?

(3) I went down a small rabbit hole trying to discover who approves such signs. I didn’t get an answer, but I did learn that the signs originated in France.

(4) We’re seeing more and more historical markers at highway rest stops, and I for one would like to say “bravo!” Not only because I love a historical marker, but because it encourages the curious to spend more time at the rest stop. After all, the point of the stop is not just to use the restroom, but to stretch the legs, rest the eyes, and fluff the brain, thereby making the next stretch of driving a little safer.

(5) Or so the popular account of history tells us. If I have learned anything in writing this blog, it is that the ideal of the “angel of the household” applied only to members of the relatively prosperous middle-class and that even within that class many women didn’t fit that mold for many reasons. Just yesterday a friend sent me the story of the team of “gentlewomen who had experienced reverses” who created the restaurants in Marshall Field’s in downtown Chicago. A very different story than that of Mother Jones, but one that also stands outside what we are taught was the nineteenth century norm.

November 22, 2022

Heading Home for Thanksgiving

As I write this, My Own True Love and I are packing for the drive from Chicago to my hometown in the Missouri Ozarks to spend the holiday with my family. As usual, the list of things I wanted to accomplish before we hit the road is longer than the time available to do them. And as usual, I am editing the list down from things I want to do to things I need to do. One thing I refused to edit off the list was this blog post.

People sometimes ask me why I write this blog, especially when I’m under the gun with a book deadline. (Don’t get me started!) The answer is simple: all of you. You don’t just read my posts. You send me comments and ideas, ask hard questions, point out the typos, and cheer me on. Thank you for being on this journey with me, whether you’ve been reading me from the beginning or you’ve just found me. There’s a lot more history out there to explore and I look forward to sharing it with you.

—————-

And speaking of sending me ideas, I getting ready to send out invitations to my annual Women’s History Month extravaganza of mini-interviews.* If you “do” women’s history in any format, or know someone who does, or just have an idea of someone you would love to see in the series, let me know. (With the caveat that I may not be able to get a big name writer to respond without a connection of some kind.)

*Some of you who know me in real life are probably saying “Are you crazy???!!!” To which I say, “yes, I am crazy” and “yes, I am doing this.”