Pamela D. Toler's Blog, page 33

February 21, 2023

From the Archives: The Crusades from A Different Perspective

In every book I write I reach the point where I am so deep in the work that I have to stop writing blog posts and newsletters. I always hope to avoid it. That somehow I’ll be smarter, or faster, or more organized, or just more. This time I’ve managed to avoid hitting the wall for several months by cutting back to one post a month. But the time has come. For the next little while, I’m going to share blog posts from the past. (This one is from 2014.) I hope you re-discover an old favorite, or read a post that you missed when it first came out.

There will be new posts in March no matter what: we celebrate Women’s History Month hard here on the Margins. (I have some fascinating people lined up.)

Recently I’ve been reading Sharan Newman’s Defending The City of God: A Medieval Queen, The First Crusade And The Quest for Peace In Jerusalem. It was a perfect read for March, which was Women’s History Month.*

Newman tells the story of a historical figure who was completely new to me. Melisende (1105-1161) was the first hereditary ruler of the Latin State of Jerusalem, one of four small kingdoms founded by members of the First Crusade. Her story is a fascinating one. The daughter of a Frankish Crusader and an Armenian princess, Melisende ruled her kingdom for twenty years despite attempts by first her husband and then her son to shove her aside. Even after her son finally gained the upper hand, Melisende continued to play a critical role in the government of Jerusalem. Those few historians who mention Melisende at all tend to describe her as usurping her son’s throne.** Newman makes a compelling argument for Melisende as both a legitimate and a powerful ruler. (In all fairness, this is the kind of argument I am predisposed to believe.)

Fascinating as Melisende’s story is, Newman really caught my attention with this paragraph:

Most Crusade histories tell of the battle between Muslims and Christians, the conquest of Jerusalem and its eventual loss. The wives of these men are mentioned primarily as chess pieces. The children born to them tend to be regarded as identical to their fathers, with the same outlook and desires. Yet many of the women and most of the children were not Westerners. They had been born in the East. The Crusaders states of Jerusalem, Edessa, Tripoli, and Antioch were the only homes they knew.

Talk about a smack up the side of the historical head!

If you’re interested in medieval history in general, the Crusades in particular, or women rulers, Defending the City of God is worth your time.

* It was also nice to spend some time in a warm dry place, if only in my imagination. Here in Chicago, March came in like a lion and went out like a cold, wet, cranky lion.

** To put this in historical context. Melisende’s English contemporary, the Empress Matilda (1102-1167) was the legitimate heir to Henry I. After Henry’s death, her cousin Stephen of Blois had himself crowned king and plunged England into a nine-year civil war to keep her off the throne. Apparently twelfth century Europeans had a problem with the idea of women rulers.

February 17, 2023

From the Archives: Eighty Days

In every book I write I reach the point where I am so deep in the work that I have to stop writing blog posts and newsletters. I always hope to avoid it. That somehow I’ll be smarter, or faster, or more organized, or just more. This time I’ve managed to avoid hitting the wall for several months by cutting back to one post a month. But the time has come. For the next little while, I’m going to share blog posts from the past. (In this case a review of one of my favorite books.) I hope you re-discover an old favorite, or read a post that you missed when it first came out.

There will be new posts in March no matter what: we celebrate Women’s History Month hard here on the Margins. (I have some fascinating people lined up.)

On November 14, 1889, Nelly Bly, reporter for the popular newspaper The World, sailed from New York on the trip that would make her famous: an attempt to travel around the world in less than eighty days. Eight and a half hours later, unknown to Bly, the literary editor of the monthly magazine, The Cosmopolitan, boarded a westbound train in a reluctant and largely forgotten attempt to beat Bly around the world. Matthew Goodman tells their story in Eighty Days: Nellie Bly and Elizabeth Bisland’s History-Making Race Around the World.

Goodman emphasizes both the differences and the surprising similarities between the brash investigative reporter from a Pennsylvania coal town and the southern lady who educated herself in a ruined plantation’s library. Alternating between their experiences, he contrasts their reactions to publicity, their fellow travelers (especially the British), and the new cultures they encounter. Even knowing that Bly will win, the race is a page-turner, complete with storms at sea, damaged ships, nearly missed connections, the kindness of strangers, and a hair-raising train ride through western mountains.

Although the race is engaging in its own right, Eighty Days is more than an adventure story. Goodman does not limit himself to a step-by-step narrative of his heroines’ travels. Instead he uses the race to illustrate the social impact of new modes of transportation, a growing popular press, and new opportunities for women. The result is a social history of America on the verge of modernity.

February 14, 2023

From the Archives: Woodrow Wilson in Love

In every book I write I reach the point where I am so deep in the work that I have to stop writing blog posts and newsletters. I always hope to avoid it. That somehow I’ll be smarter, or faster, or more organized, or just more. This time I’ve managed to avoid hitting the wall for several months by cutting back to one post a month. But the time has come. For the next little while, I’m going to share blog posts from the past. I hope you enjoy an old favorite, or read a post that you missed when it first came out.

There will be new posts in March no matter what: we celebrate Women’s History Month hard here on the Margins. (I have some fascinating people lined up.)

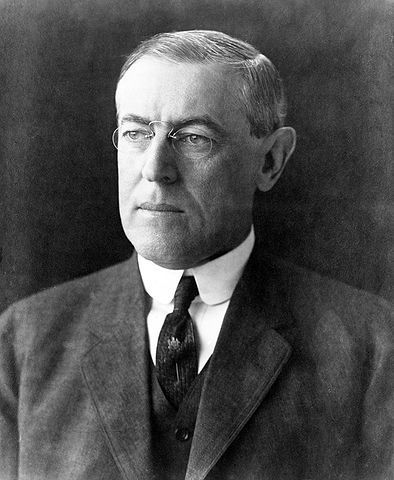

In honor of Valentine’s day, I want to share one of my favorite stories about President Woodrow Wilson, reported by Secret Service agent Edmund Starling in his memoir of the Wilson White House:*

En route to his honeymoon destination with his second wife, Edith Bolling Galt Wilson, the president was seen dancing a jig by himself and singing the chorus of a popular song: “Oh you beautiful doll! You great big beautiful doll…” Starling reports that the president even clicked his heels in the air.

Look closely at the portrait of the president at the top of this post. Add a top hat, pushed back. Picture him dancing and singing. Makes me smile every dang time.

Now if you’ll excuse me, I’m off to give My Own True Love a kiss. I may even click my heels in the air and sing a love ditty.

*My apologies to those of you who’ve read it here before or heard me tell the story in person (complete with song and dance step).

February 11, 2023

From the Archives: Shin-Kickers from History -Olaudah Equiano

In every book I write I reach the point where I am so deep in the work that I have to stop writing blog posts and newsletters. I always hope to avoid it. That somehow I’ll be smarter, or faster, or more organized, or just more. This time I’ve managed to avoid hitting the wall for several months by cutting back to one post a month. But the time has come. For the next little while, I’m going to share blog posts from the past. (This one is from 2015.) I hope you enjoy an old favorite, or read a post that you missed when it first came out.

There will be new posts in March no matter what: we celebrate Women’s History Month hard here on the Margins. (I have some fascinating people lined up.)

Most accounts of the slave trade were written by slave traders, or by people dedicated to abolishing the slave trade. Few accounts were written by the slaves themselves. One important exception is The Interesting Narrative of Olaudah Equiano, published in 1789.

Olaudah Equiano was born in 1745 in what is now Nigeria. When he was ten or eleven, he was kidnapped and sold as a slave in Barbados. He did not remain in Barbados long. He was sold first to a planter in Virginia and three months later to a British naval officer. He spent most of his time as a slave working on British slave ships and naval vessels. One of his owners, Henry Pascal, the captain of a British trading ship, gave Equiano the name Gustavas Vassa, which he used for most of his life.

In 1762, Equiano was sold to Robert King, a Quaker merchant from Philadelphia. King allowed Equiano to trade small amounts of merchandise on his own behalf. He earned enough money to buy his freedom in 1766.

Once free, Equiano settled in England, where he worked as a merchant and became active in the abolition movement there. At the urging of his abolitionist friends, he wrote a memoir describing his capture and his experiences as a slave. The book was clearly designed as part of the movement: it began with a petition to Parliament and ended with an antislavery letter addressed to Queen Charlotte.* Although he included horrifying tales of the middle passage and West African slavery, he focused on his personal story–countering the popular image of the African slave as a heathen savage with that of a middle-class Englishman who improved his fortunes with hard work and just happened to be black.

The time of its publication in 1789 was good. William Wilberforce had brought his first bill for the abolition of the slave trade before Parliament. Abolitionist committees were flooding the country with copies of the shocking diagram of the slave ship The Brookes. With abolition in the air, The Interesting Narrative of Olaudah Equiano, or Gustavus Vassa the African, Written by Himself became an international best seller. ** Equiano did his part to make that happen. He traveled across the British Isles for five years promoting his book and his cause.***

Equiano died in 1797. It was 1807 before Parliament declared the slave trade illegal in Britain.

* No point in addressing it to the king. George III was known to be pro-slavery, or at least anti-abolition. The man always backed the wrong historical horse.

**It’s still in print today.

***Speaking as an author who has tried to actively promote a book for a period of months, this exhausts me just to think about.

February 7, 2023

From the Archives: Liar, Temptress, Soldier, Spy

In every book I write I reach the point where I am so deep in the work that I have to stop writing blog posts and newsletters. I always hope to avoid it. That somehow I’ll be smarter, or faster, or more organized, or just more. This time I’ve managed to avoid hitting the wall for several months by cutting back to one post a month. But the time has come. For the next little while, I’m going to share blog posts from the past. (This one is from 2015.) I hope you enjoy an old favorite, or read a post that you missed when it first came out.

There will be new posts in March no matter what: we celebrate Women’s History Month hard here on the Margins. (I have some fascinating people lined up.)

Nursing wasn’t the only role that women played in the American Civil War. Women on both sides of the conflict organized soldier’s aid societies, effectively transforming homes, schools and churches into small-scale factories and shipping warehouses in which they made and collected food, clothing and medical supplies. Eighty years before Rosie the Riveter, they worked in munitions factories, loading paper cartridges by hand. In the north, hundreds of women took over desk jobs in the growing Federal government, freeing up men to fight.*

Other women stepped even further outside of social norms. Several hundred women cut off their hair, disguised themselves as men, and enlisted to fight. Others used society’s assumptions about what women can/should/don’t/shouldn’t do as an effective cover for spying

In Liar, Temptress, Soldier, Spy, Karen Abbott tells the stories of four very different women who went undercover during the Civil War. Seventeen-year-old Belle Boyd, described by a contemporary as “the fastest girl in Virginia or anywhere else for that matter”, was a courier and spy for the confederate army, using her feminine wiles and her lack of maidenly modesty to manipulate men in both armies. Rose O’Neal Greenhow was a “merry widow” who formed a Confederate spy ring in Washington.** Her Union counterpart was Elizabeth Van Lew, a wealthy maiden lady in Richmond who was a known abolitionist and Union sympathizer. Disguising her actions under the guise of proper ladylike behavior, she ran an extensive and daring information network under the nose of her Confederate in-laws, with whom she shared a home. Emma Edmondson had disguised herself as a man for personal reasons two years before the war and traveled as a Bible salesman. When the war broke out, she enlisted in a Michigan regiment as Frank Thompson.

Taken together, their stories explore the boundaries of nineteenth century assumption about the roles of women. Which sounds ponderous. Trust me, in Abbott’s hands it’s anything but dull. Liar, Temptress, Soldier, Spy: Four Women Undercover in the Civil War is a rollicking good read.

*Unlike Rosie the Riveter, many women kept their new jobs after the war was over. One of the things that we tend to forget about war is the holes left by the men who don’t come back, not only in families but in society as a whole.

**I’ve always found it difficult to understand why a man in possession of critical military information doesn’t have warning lights flash in his head when the woman he’s having an illicit affair with wants to talk troop movements.

***Which is a big assumption, because I realize that people discover this blog and individual posts long after the fact. If you’re new here, welcome!

February 3, 2023

From the Archives: Fatherland

In every book I write I reach the point where I am so deep in the work that I have to stop writing blog posts and newsletters. I always hope to avoid it. That somehow I’ll be smarter, or faster, or more organized, or just more. This time I’ve managed to avoid hitting the wall for several months by cutting back to one post a month. But the time has come. For the next little while, I’m going to share blog posts from the past. (This one is from 2015.) I hope you enjoy an old favorite, or read a post that you missed when it first came out.

There will be new posts in March no matter what: we celebrate Women’s History Month hard here on the Margins. (I have some fascinating people lined up.)

*

If you dismiss history told in comic book graphic form* as the non-fiction equivalent of Classic Comics, you’re missing out. At its best, graphic non-fiction uses visual elements to tell stories in new and powerful ways.**

In her graphic memoir, Fatherland: A Family History, Serbian-Canadian artist Nina Bunjevac tells the blood-soaked history of the former state of Yugoslavia through the lens of one family’s story.

In her graphic memoir, Fatherland: A Family History, Serbian-Canadian artist Nina Bunjevac tells the blood-soaked history of the former state of Yugoslavia through the lens of one family’s story.

Fatherland centers on Bunjevac’s father, whose involvement in a Canadian-based Serbian terrorist organization led her mother to flee with her daughters to Yugoslavia in 1975 and ended with his death in a bomb explosion. Moving back and forth in time and place, from modern Toronto to Yugoslavia during both the Nazi occupation and the Cold War, Bunjevac explores the steps that led to her father’s extreme nationalism and its tragic consequences. Using a combination of strong lines, pointillism and cross-hatching that evokes the feeling of an old newspaper, she tells a story in which there are no heroes and every choice, personal or political, has traumatic consequences. (Bunjevac’s mother is forced to make a classic “Sophie’s choice”: the only way she can take her daughters to Yugoslavia is to leave her son behind.) Both the country and Bunjevac’s family are torn apart by the bitter divisions between Serbs and Croats, partisans and collaborators, royalists and communists.

Bunjevac makes no moral judgments about her family’s choices. Instead she approaches their history from several viewpoints, introducing increasing complexity and moral ambiguity with each new layer. The only thing that is black and white in Fatherland is Bunjevac’s exquisite and often grim illustrations.

*As opposed to what we call “comic book history” here at the Margins–stories that are culturally entrenched and often emotionally satisfying but untrue.

**At its worst, graphic non-fiction is garish and heavy-handed. But if we abandon entire genres of literature based only on the worst examples we’ll have nothing left to read.

January 31, 2023

From the Archives: Word with a Past–Two Bits

In every book I write I reach the point where I am so deep in the work that I have to stop writing blog posts and newsletters. I always hope to avoid it. That somehow I’ll be smarter, or faster, or more organized, or just more. This time I’ve managed to avoid hitting the wall for several months by cutting back to one post a month. But the time has come. For the next little while, I’m going to share blog posts from the past. (This one is from 2013. Time flies.) I hope you enjoy an old favorite, or read a post that you missed when it first came out.

There will be new posts in March no matter what: we celebrate Women’s History Month hard here on the Margins. (I have some fascinating people lined up.)

One of the favorite cheers for my junior high school’s football team went “Two bits, four bits, six bits, a dollar, all for our team stand up and holler.” It made no sense to me, but neither did football. When the rest of the Trojan fans stood up and hollered, I stood up and hollered. When they said glumly in the stands, I sat. By high school, my best friends were all in marching band, I was therefore freed of my weekend football obligation, and I knew that “two bits” meant a quarter–I just didn’t know why.

Turns out the phrase has its roots in the Spanish conquest of the Americas and the river of silver that flowed from the mines of Potosí to the royal coffers in Madrid. (1)

In 1497, their Most Catholic Majesties Ferdinand and Isabella introduced a new coin into the global economy as part of a general currency reform. The peso (literally “weight”) was a heavy silver coin that was worth eight reales.(2) In Spanish it became known as a peso de ocho(3); in English it was a “piece of eight”.

The peso quickly became a global currency. It was relatively pure silver, it was uniform in size and weight, and it had one special characteristic: it could be divided like a pie into eight reales. In English, those reales became known as “bits”. Two bits were a quarter of a peso. After the new American Congress based the weight of the American dollar on the peso in 1792(4), “two bits” also referred to a quarter of a dollar.

Now I need to figure out what “Two in ten, let’s do it again” means.

(1)And flowed right back out again to pay for spices, textiles and other luxury goods in the India trade.

(2) The important word here is EIGHT, not reales. The story would be the same if it were eight goats, eight marbles, or eight football fans.

(3) For those of you who never had to count to ten in Spanish, ocho means EIGHT.

(4) Choosing to base American currency on the peso rather than the pound was a not-so-subtle way to spit in Great Britain’s eye. The peso remained legal tender in the US until the 1850s.

January 27, 2023

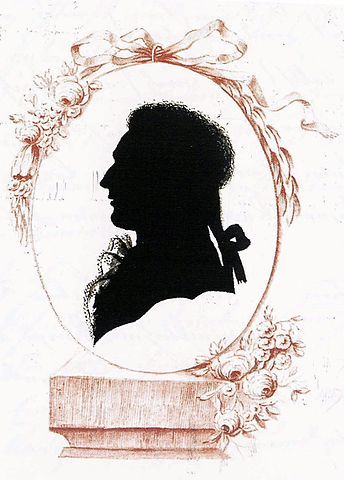

From the Archives: Word With a Past-Silhouette

In every book I write I reach the point where I am so deep in the work that I have to stop writing blog posts and newsletters. I always hope to avoid it. That somehow I’ll be smarter, or faster, or more organized, or just more. This time I’ve managed to avoid hitting the wall for several months by cutting back to one post a month. But the time has come. For the next little while, I’m going to share blog posts from the past. (This one is from 2013. Time flies.) I hope you enjoy an old favorite, or read a post that you missed when it first came out.

There will be new posts in March no matter what: we celebrate Women’s History Month hard here on the Margins. (I have some fascinating people lined up.)

I’m poking around in the long eighteenth century these days and stumbling across lots of surprising tidbits.

Take silhouettes. I had long known that charming likenesses cut from black cardstock became a popular and affordable alternative to oil portraits in the mid-eighteenth century. To the extent that I thought about the word at all, I assumed it was the name of a clever scissors-wielding artist who started the new fashion.

Wrong.* The art form, originally called “shades” or “profiles”, pre-dated the name.

Étienne de Silhouette was a French attorney with intellectual leanings and political ambitions. He wrote treatises on this and that, translated Alexander Pope into French, made friends with Madame Pompadour, and earned a name as a garçon fort savant** for a book he wrote on the English taxation system. That book would get him in trouble.

In 1759, halfway through the Seven Years War, he was appointed Controller-General of France. The war was expensive and Silhouette had the thankless job of balancing a budget with a shortfall of 217 million livres.*** To make things harder, more than sixty years of almost constant warfare, had left France with a shortage of metal money and a budget crippled by existing debt. Silhouette issued some long-term debts and cut some expenses, but he realized that the long term answer was raising tax income. He took the not-unreasonable position that the easiest people to raise money from were the people who had money–especially true in the Ancién Regime, where the nobility and the clergy were exempt from taxes. He took away their tax exemptions and cancelled a range of pensions, sinecures, and handouts. With the wealthy and powerful already in an uproar, he then instituted new taxes on luxury goods, from jewelry and carriages to servants and windows. The marquise du Deffand, writing to Voltaire, complained “they are not taxing the air we breathe, but apart from that, I can’t think of anything that’s escaped.”

Less than nine months after his appointment, Silhouette was out on his ear and the term à la Silhouette was applied to anything cheap, including the profile portraits known as shades.

* In more ways than one, it turned out. Evidently there were two schools of silhouette artists, cutters and painters. The things you find out when you follow a fact down a rabbit hole.

** Bright kid

***Roughly 459 billion dollars today ****

****Very roughly, since I had to work from livres to francs, then calculate it forward to 1800 and convert it into dollars before I could plug it into this currency converter.

January 24, 2023

From the Archives: The Museum of Memory and Human Rights

In every book I write I reach the point where I am so deep in the work that I have to stop writing blog posts and newsletters. I always hope to avoid it. That somehow I’ll be smarter, or faster, or more organized, or just more. This time I’ve managed to avoid hitting the wall for several months by cutting back to one post a month. But the time has come. For the next little while, I’m going to share blog posts from the past. (This one is from 2014. Time flies.) I hope you enjoy an old favorite, or read a post that you missed when it first came out.

There will be new posts in March no matter what: we celebrate Women’s History Month hard here on the Margins.

The Bombing of La Moneda (the Chilean equivalent of the White House) on September 11, 1973, by the Junta’s Armed Forces.

My Own True Love and I went to Chile over the holidays for a family wedding and a spot of adventure. We set off knowing where we needed to be when and no idea about the details. We discovered strawberry juice, pisco sours, enormous holes in our knowledge of Chilean history, and the amazing kindness of strangers. We spent two nights in a cabin that looked like a hobbit hole, walked in the foothills of the Andes, and stayed up much later than we are used to.

Along the way we visited a truly powerful museum: the Museo de la Memoria et los Derechos Humanos (The Museum of Memory and Human Rights).

The museum documents the events of the military coup of September 11, 1973, the subsequent abuses of the Pinochet years, the courage of those who stood against the regime, and the election in which Chile voted Pinochet out of power in 1988.* The exhibits are an assault on the senses, using contemporary film clips, music, photographs, and recordings. Photographs of the regime’s victims “float” against a glass wall that is two-stories high. Interviews with survivors of the coup were fascinating; interviews with survivors of the government’s human rights abuses were almost unbearable. A recording of President Allende’s final speech, broadcast under siege from the presidential palace shortly before his death, was awe-inspiring. In short, the museum shows humanity at its best and its worst.

In many ways, the Museo de la Memoria resembles Holocaust museums we’ve visited, not only in its insistence on memory and celebration of survival, but in its message of “never again”. A quotation from former Chilean president Michelle Bachelet Jeria is engraved at the entrance that sums up the museum’s purpose: “We are not able to change our past. The only thing that remains to us to learn from the experience. It is our responsibility and our challenge.” Statements about and explanations of the universal declaration of human rights, passed by the United Nations in 1948, are interwoven throughout the historical exhibits.

I cannot say we had a fun morning. My Own True Love and I left the museum drained. We also were very pleased we made the effort. If you are lucky enough to have the chance to visit Chile, make the time to visit. If you don’t see Chile in your future but would like to know more about Chile under the Pinochet regime, these two books come highly recommended: Andy Beckett’s Pinochet in Piccadilly: Britain and Chile’s Hidden History and Hugh O’Shaughnessy’s Pinochet: The Politics of Torture. I haven’t read either of them yet, but I’m putting them on my need-to-read list.

*I don’t know of any other instance in which a dictatorship allowed itself to be voted out of power. Do you?

Photograph courtesy of the Library of the Chilean National Congress

January 20, 2023

From the Archives: Eternity Street

In every book I write I reach the point where I am so deep in the work that I have to stop writing blog posts and newsletters. I always hope to avoid it. That somehow I’ll be smarter, or faster, or more organized, or just more. This time I’ve managed to avoid hitting the wall for several months by cutting back to one post a month. But the time has come. For the next little while, I’m going to share blog posts from the past, starting with this one from 2019. I hope you enjoy an old favorite, or read a post that you missed when it first came out.

There will be new posts in March no matter what: we celebrate Women’s History Month hard here on the Margins.

Historian John Mack Faragher has spent his career writing about frontiers in general and the American West specifically. In Eternity Street: Violence and Justice in Frontier Los Angeles, he considers the structure and culture of violence in a frontier society, how violence reproduces and polices itself in a so-called “honor culture,”* and the slow development of an official justice system in Los Angeles in the mid-nineteenth century. The result is a fascinating look at the competing forces of official justice and vigilantism as southern California moved from Mexican to American control.

Drawing on a combination of official records, contemporary newspaper accounts, personal papers, memoirs and autobiographies, Faragher tells individual stories of murder, retaliation, domestic violence, racism and greed. At the same time, he never loses sight of the larger history of the region. He sets detailed accounts of conflicts between individuals within the contexts of the conquest of southern California by first Mexico and then the United States, the Texas rebellion, the American Civil War and the gold rush of 1848.

This is not the American West of American fable. Faragher’s Los Angeles is a frontier outpost with no white-hatted heroes and plenty of ethnic conflict. Native Americans newly freed from control of the missions, native angeleños, African-American slaves and freedmen, North American adventurers, and the United States Army and Navy compete for resources, political control, and women with blades, guns and lances.***

Eternity Street is an ugly story, beautifully told.

*It’s easy to idealize honor culture in the past: medieval knights, eighteenth century duelists, and samurai warriors all enjoy a certain glamour in popular culture. A quick look at how it plays out in street gangs makes it clear that honor culture centers on male violence. It’s cock fighting, with men instead of roosters.

** At one point in the narrative, the United States Army and Navy came close to armed conflict with each other over who was in charge, suggesting an honor culture of a different variety.