Elisabeth Storrs's Blog, page 7

July 7, 2019

Guest post: Women Writers, Women’s Books

Many thanks to Women Writers, Women’s Books for inviting me to write a guest post on Inspiration and Obsession for the blog. Inspiration ignites the spark to imagine a novel; obsession fans the flames to fuel the journey to complete it.

On Inspiration: Interview with J.L.Oakley

My guest today is JL Oakley who writes award-winning historical fiction that spans the mid-19th century to WW II. Her characters, who come from all walks of life, stand up for something in their own time and place. Her writing has been recognized with the 2013 Chanticleer Grand Prize, the 2014 First Place Chaucer Award, 2015 WILLA Silver Award and the 2016 Goethe Grand Prize. When not writing, she demonstrates 19th century folkways – and can churn some pretty mean butter. You can connect with her via her website, Facebook, Twitter and Pinterest. You can find all her books on Amazon.

My guest today is JL Oakley who writes award-winning historical fiction that spans the mid-19th century to WW II. Her characters, who come from all walks of life, stand up for something in their own time and place. Her writing has been recognized with the 2013 Chanticleer Grand Prize, the 2014 First Place Chaucer Award, 2015 WILLA Silver Award and the 2016 Goethe Grand Prize. When not writing, she demonstrates 19th century folkways – and can churn some pretty mean butter. You can connect with her via her website, Facebook, Twitter and Pinterest. You can find all her books on Amazon.

What or who inspired you to first write? Which authors have influenced you?

Ha. I started writing in second grade. (Seems like a common theme with some writers) But it’s true. I think after it was after attending a movie about Edmund Hillary’s climb on Mount Everest, I was inspired to write Funny Bunny Climbs Mount Everest, complete with illustrations. I wrote a few more after that. Through school I wrote stories and essays. It wasn’t until college where I majored in history, did I begin to hone my skills in research that would become the way I prepare for writing my historical fiction and now, cozy mysteries with history. I didn’t write my first novel until I was in my forties and that came from a dream. I had never tackled a novel in my life. The novel became award-winning The Jøssing Affair.

My mom turned me on to historical fiction when I was in fifth grade. Captain Blood, The Prince of Foxes were some of her favourites, but I was also into Little House on the Prairie and other books. I think all of these were influencers. Currently, I’m enjoying Jamie Ford’s novels and Love and Ruin by Paula Mclaim. She also wrote The Paris Wife. I also read a lot of non-fiction.

What is the inspiration for your current book? Is there a particular theme you wished to explore?

I’m a University of Hawaii Manoa grad and ever since I moved to Washington State forty years ago, I have been fascinated with the history of Hawaiians living and working in the Pacific NW since early 1800. I’ve always wanted to write about them. Mist-chi-mas: A Novel of Captivity is set on San Juan Island in 1860. The island was jointly occupied by the US Army and the Royal Marines while an international water boundary dispute was solved. Since 1853, Hawaiians, Kanakas as they were called then, lived and worked on the island for the Hudson’s Bay Company, herding sheep and doing other farm activities. Kanaka Town, a real place near this HBC farm, is featured in the novel as well as several Kanaka characters.

I’m a University of Hawaii Manoa grad and ever since I moved to Washington State forty years ago, I have been fascinated with the history of Hawaiians living and working in the Pacific NW since early 1800. I’ve always wanted to write about them. Mist-chi-mas: A Novel of Captivity is set on San Juan Island in 1860. The island was jointly occupied by the US Army and the Royal Marines while an international water boundary dispute was solved. Since 1853, Hawaiians, Kanakas as they were called then, lived and worked on the island for the Hudson’s Bay Company, herding sheep and doing other farm activities. Kanaka Town, a real place near this HBC farm, is featured in the novel as well as several Kanaka characters.

In Mist-chi-mas, I explore the theme of captivity. Mischimas means “captive” and sometimes “slave” in Chinook Jargon, a trade language spoken in the Pacific NW during this time. There is captivity for many of the characters. Jeannie Naughton, a young Englishwoman, is captive to the norms of the period regarding women, in what they could and could not do. A woman’s reputation was everything and a whiff of scandal could ruin her. Jonas Breed, an American frontiersman, is a true mistchimas, having been captured by the Haida, a “northern” tribe that came down from the Queen Charlotte Islands in what was British America. They often terrorized local Indians and settlers alike. Breed is free at the opening of the novel. Kanakas and Coast Salish Indians are captive in their own ways to the changing landscape as Americans and British citizens grow in numbers and impose their cultures and political systems on them. Throw in smugglers dealing with whiskey and prostitution on the island and you have tension. In 1860, the Pacific NW was a genuine multi-culture melting pot.

What period of history particularly inspires or interests you? Why?

I’ve always been interested in pioneers, so Mist-chi-mas, set on San Juan Island in the Pacific NW in 1860 is an easy fit. I’m currently working on a novel set in 1864 during the American Civil War. However, the 20th century, especially the years 1900 to 1946 have been the focus of the bulk of my work. Why? Maybe because of personal stories passed down through my family. They have led me to explore the history in the times they recalled. Tree Soldier, a novel about the Depression era Civilian Conservation Corps, came out of my mom’s encounters with CCC boys up at her uncle’s Idaho ranch in 1933. A WIP set during the Civil War comes from my great-grandfather who was a Union surgeon at the Battle of Gettysburg. Sometimes it’s plain curiosity that leads me write about a period. A 1907 book, What Every Young Wife Ought to Know, got me curious about married couples in this time period when women were going for the vote, dreaming about being a “new woman” and climbing mountains in skirts. That novel is Timber Rose. The 1907 book has absolutely no useful information on what woman should know, including the wedding bed.

I’ve always been interested in pioneers, so Mist-chi-mas, set on San Juan Island in the Pacific NW in 1860 is an easy fit. I’m currently working on a novel set in 1864 during the American Civil War. However, the 20th century, especially the years 1900 to 1946 have been the focus of the bulk of my work. Why? Maybe because of personal stories passed down through my family. They have led me to explore the history in the times they recalled. Tree Soldier, a novel about the Depression era Civilian Conservation Corps, came out of my mom’s encounters with CCC boys up at her uncle’s Idaho ranch in 1933. A WIP set during the Civil War comes from my great-grandfather who was a Union surgeon at the Battle of Gettysburg. Sometimes it’s plain curiosity that leads me write about a period. A 1907 book, What Every Young Wife Ought to Know, got me curious about married couples in this time period when women were going for the vote, dreaming about being a “new woman” and climbing mountains in skirts. That novel is Timber Rose. The 1907 book has absolutely no useful information on what woman should know, including the wedding bed.

What resources do you use to research your book? How long did it take to finish the novel?

I try to read as much as I can, scouring bibliographies and primary resources. Today, good resources can be found on-line and an email to a historical society or museum can bring great results. I’ve joined Facebook groups on subjects I’m interested in. Sometimes a leap of faith to an organization can be very useful. When I needed information on hand surgery in 1946, I wrote to the National Association of Hand Surgeons and was referred to their education head. Got my character’s surgery right for the times.

I try to read as much as I can, scouring bibliographies and primary resources. Today, good resources can be found on-line and an email to a historical society or museum can bring great results. I’ve joined Facebook groups on subjects I’m interested in. Sometimes a leap of faith to an organization can be very useful. When I needed information on hand surgery in 1946, I wrote to the National Association of Hand Surgeons and was referred to their education head. Got my character’s surgery right for the times.

I started writing Mist-chi-mas eighteen years ago. It was done in about a year and half. Then my critique suggested that I not write back and forth between two time lines and just tell it straight through with a break of twenty years in the next section. Of course, I had to explain why certain people were in the second half and how they fit into the first. In rewriting the novel, it became a richer story. A Kanaka name Kapihi was only ten years old in 1860. He is the link between 1860 and 1880. After putting the manuscript into my editor’s hand, Mist-chi-mas was published in 2017.

What do you do if stuck for a word or a phrase?

Just write the scene anyway. You can always go back.

Is there anything unusual or even quirky that you would like to share about your writing?

Not sure about quirky, but I do love to write about people, facts, and times that aren’t well known. Hawaiians in the NW always throw people off especially when they learn that Friday Harbor, a very popular tourist destination on San Juan Island was actually named by a Kanaka who worked for HBC, Joseph Friday. Friday’s Harbor, sailors knew in the 1850s, had a deep harbor. When they saw his lantern in his hut up on the bluff, they knew they could safely anchor.

Do you use a program like Scrivener to create your novel? Do you ever write in long hand?

I don’t use Scrivener. Just Word. I just learned how to use Styles in the program which makes for a very good manuscript. I often start off in long hand with pencil, especially with a new scene or chapter, then gradually put it on the computer. I print off and write by hand again when I’m out and about. The Jøssing Affair was written almost entirely by hand until I got a computer. That was twenty-six years ago.

Is there a particular photo or piece of art that strikes a chord with you? Why?

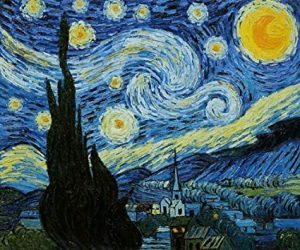

I had to think about this, but I would say ‘Starry Night’ by Van Gogh. Maybe it’s that moving song by Don Mclean that captures Van Gogh’s pain or being in Arles, France a few years ago where some of the versions of the painting were created. While there I saw where he was hospitalized for the first time. Maybe I’m drawn even more after being in Arles when our tour went down to where he was hospitalized for months, yet did some of his most iconic work. I have personal experience with mental illness in the family. It makes the painting so full of energy, so empathetic. Song and painting go together.

I had to think about this, but I would say ‘Starry Night’ by Van Gogh. Maybe it’s that moving song by Don Mclean that captures Van Gogh’s pain or being in Arles, France a few years ago where some of the versions of the painting were created. While there I saw where he was hospitalized for the first time. Maybe I’m drawn even more after being in Arles when our tour went down to where he was hospitalized for months, yet did some of his most iconic work. I have personal experience with mental illness in the family. It makes the painting so full of energy, so empathetic. Song and painting go together.

What advice would you give an aspiring author?

Don’t be afraid of being stuck with words. Write down that scene that is your head. It doesn’t matter where it fits in your story. You can find its place later. Create bios for your characters. Not just what they look like, but what they fear, their secrets, their joys. Even an object that goes with them. It’s a Hollywood thing, but readers do catch the relationship between character and object. In Mist-chi-mas it’s a thimble. In The Jøssing Affair it’s a fish hook. Just write!

Tell us about your next book.

I’m working hard on the sequel to The Jøssing Affair. It’s set in Norway in 1946 and surrounds the war crimes trials. I’m about half way through what should be ACT II. I hope to have a good rough draft by October. In the meantime, I published my three Hawaiian cozy mysteries with history in April as a paperback and ebook collection. The Hilo Bay Mystery Collection novellas were originally a part of a Kindle World. With rights back and rewritten, they have been a lot of fun to put out there. A fourth novella will have to be totally reimagined. I may tackle that this summer and publish in the fall.

I’m working hard on the sequel to The Jøssing Affair. It’s set in Norway in 1946 and surrounds the war crimes trials. I’m about half way through what should be ACT II. I hope to have a good rough draft by October. In the meantime, I published my three Hawaiian cozy mysteries with history in April as a paperback and ebook collection. The Hilo Bay Mystery Collection novellas were originally a part of a Kindle World. With rights back and rewritten, they have been a lot of fun to put out there. A fourth novella will have to be totally reimagined. I may tackle that this summer and publish in the fall.

Many thanks, Janet. I love the fact you explore different nooks and crannies of history.

In Mist-chi-mas, everyone is bound to something.

Jeannie Naughton never intended to run away from her troubles, but in 1860, a woman’s reputation is everything. A scandal not of her own making forces her to flee England for an island in the Pacific Northwest, a territory jointly occupied by British and American military forces. At English Camp, Jeannie meets American Jonas Breed. Breed was once a captive and slave — a mistchimas — of the Haida, and still retains close ties to the Coast Salish Indians.

But the inhabitants of the island mistrust Breed for his friendship with the tribes. When one of Breed’s friends is murdered, he is quickly accused of a gruesome retaliation. Jeannie knows he’s innocent, and plans to go away with him, legitimizing their passionate affair with a marriage. But when she receives word that Breed has been killed in a fight, Jeannie’s world falls apart. Although she carries Jonas Breed’s child, she feels she has no choice but to accept a proposal from another man.

Twenty years later, Jeannie finds reason to believe that Breed may still be alive. She must embark on a journey to uncover the truth, unaware that she is stirring up an old and dangerous struggle for power and revenge…

June 23, 2019

The History Girls: Ancient ‘Girl Power’

My recent post on The History Girls deals with Ancient ‘Girl Power’ that dates back millenia. Compare the influence and eminence of Etruscan women to their Roman and Greek sisters.

June 2, 2019

Why the History comes before the Mystery by M. Louisa Locke

My guest today is the wonderful M Louisa Locke, USA Today Best-selling author of the Victorian San Francisco Mystery series. She is a retired professor of U.S. and Women’s History who embarked on a second career as an historical fiction writer. The series features Annie Fuller, a boardinghouse owner and pretend clairvoyant, and Nate Dawson, a San Francisco lawyer, who together with family and friends from the O’Farrell Street boarding house investigate murders and other crimes.

My guest today is the wonderful M Louisa Locke, USA Today Best-selling author of the Victorian San Francisco Mystery series. She is a retired professor of U.S. and Women’s History who embarked on a second career as an historical fiction writer. The series features Annie Fuller, a boardinghouse owner and pretend clairvoyant, and Nate Dawson, a San Francisco lawyer, who together with family and friends from the O’Farrell Street boarding house investigate murders and other crimes.

Having achieved a world wide readership with her cozy mysteries, she decided to spread her wings and write a sweet coming of age science fiction series as part of an open source, multiple author Parisdisi Chronicles. I hope you enjoy Locke’s peek into her reasoning as to why the history, not the mystery, comes first when writing an historical whodunnit. You can connect with M Louisa Locke via her website, Twitter, Facebook and Bookbub.

Why the History comes before the Mystery

One of the classic conflicts that confront fictional detectives (and I assume real ones) is whether to start with a theory about who is the most logical suspect to have committed a crime and then looking for evidence to support that theory (deductive reasoning) or to start looking at the evidence and see where it leads (inductive reasoning.) For an example, see this amusing discussion of Sherlock Holmes and whether or not he used deductive or inductive reasoning.

As someone who writes historical mysteries, I confront a similar choice. Do I start with a mystery—and look for historical detail (the evidence) to support that mystery––or do I start with the history (the evidence) and from that construct the mystery plot?

As someone who writes historical mysteries, I confront a similar choice. Do I start with a mystery—and look for historical detail (the evidence) to support that mystery––or do I start with the history (the evidence) and from that construct the mystery plot?

After examining this question for a Pacific Northwest Writers Association panel I participated in last year, I realized that I am someone who prefers to start with the history. From what I learn from my historical research, I then develop the mystery (including the nature of the crime, how the crime was committed, and who did it and why they did it.)

This seems to have been my pattern from the start. I came up with the mystery at the core of Maids of Misfortune, my first Victorian San Francisco mystery, while I was working on my doctorate in history. The topic of my dissertation was women who worked in the far western United States in the end of the 19th century, and in a diary by Anna Harder, a San Francisco servant, I read how frustrated she was by the fact every week when she returned to work after her night out, the mistress would fail to get up and open the back door, as promised, leaving the poor servant sitting, shivering, on the back steps.

As an avid mystery reader, I couldn’t help but think that this was the perfect plot for a classic “locked door” mystery. A mystery an amateur detective would solve by going undercover as a servant. More importantly, a mystery that would give me a chance to expose a much wider audience to information about what life was really like for 19th century domestics than any monograph that might come from my dissertation research.

As an avid mystery reader, I couldn’t help but think that this was the perfect plot for a classic “locked door” mystery. A mystery an amateur detective would solve by going undercover as a servant. More importantly, a mystery that would give me a chance to expose a much wider audience to information about what life was really like for 19th century domestics than any monograph that might come from my dissertation research.

From that point on, with each book in my series, I start by researching a specific aspect of women’s lives in San Francisco—having no clue about what crime I am actually going to have my protagonists solve. In the case of the fourth book in my series, Deadly Proof, the subject of my research was women who worked in the printing industry in San Francisco in the 1870s and 1880s.

In the process of learning all about the female typesetters and the local companies that were run by and/or hired them in San Francisco (with the help of a wonderful book entitled Women in Printing: Northern California, 1857-1890) I found a mention of a printing press owner, Mr. Bacon, who had come under scrutiny because of accusations of unfair labor practices.

Tracking down the state labor report about Bacon, I found additional detail. Unlike most male printers in San Francisco, Mr. Bacon primarily hired very young women as typesetters, forcing them to sign apprenticeship contracts that were considered quite exploitative. These contracts stipulated that these women rent rooms in boarding houses Bacon owned and gave him the right to hold back a proportion of their wages until they completed their apprenticeships. Bacon was also accused of “interfering” with some female employees (with an echo of the modern #metoo movement), and the contract said that if a woman left his employ before the apprenticeship was completed, he could keep all their back wages. In addition, Bacon was accused of using the low wages he paid these women to undercut his competitors—driving them out of business.

From this background research came my mystery.

I now had a fictional victim (a wealthy, womanizing printer) and lots of potential suspects with perfectly good (and historically accurate) motives for wanting him dead. I even discovered the murder weapon from a catalog of typesetting tools. Deadly Proof, the result of this research, also won first place in historical mystery category of the Chanticleer Mystery and Mayhem Awards last year (and is currently free as an ebook until June 6.)

When I started research on Scholarly Pursuits, the most recent novel in my mystery series, a similar process unfolded. My only agenda at the start of my research was to take some of my series characters across the San Francisco Bay to solve a crime on the first University of California campus at Berkeley.

When I started research on Scholarly Pursuits, the most recent novel in my mystery series, a similar process unfolded. My only agenda at the start of my research was to take some of my series characters across the San Francisco Bay to solve a crime on the first University of California campus at Berkeley.

I was primarily curious about what life was like for female college students at a state-supported university in 1881, a time period when women made up only a third of the students in American four-year colleges.

What I did not expect was to discover that the Berkeley campus was torn by a fierce debate over whether or not to ban fraternities. In fact, if you had asked me before I embarked on the research for this book, I would have guessed that there weren’t any fraternities on such a recently-established school (which opened its doors in 1868, and located to its permanent campus at Berkeley in 1873.)

I was wrong.

Not only were there five fraternities, but I learned that some students (some of whom started an anti-fraternity paper) blamed these fraternities for a number of problems on campus, including drunken beer bashes, the destruction of local property, brutal hazings of fellow students that resulted in a shooting and a Grand Jury report, and the publication of “bogus program” for an annual event that was seen as so scurrilous that it resulted in mass suspensions.

What I also discovered was my mystery—and a story I would never have written if I had come to this project with a pre-conceived plot.

In short, like the detective who doesn’t want to bias their investigations by starting out with assumptions (like the spouse is always the most likely suspect, or money is at the root of all criminal activity), I have found that starting my mysteries with the history leads to richer and more unexpected plots.

“Something is rotten in the state of Berkeley”

–1881 Blue and Gold Yearbook, University of California: Berkeley

In Scholarly Pursuits, the sixth full-length novel in the USA Today best-selling Victorian San Francisco mystery series, Locke explores life on the University of California: Berkeley campus in 1881, where Laura and her friends face the remarkably modern problems of fraternity hazings, fraught romantic relationships, and fractious faculty politics.

While Annie and Nate Dawson and friends and family in the O’Farrell Street boardinghouse await a blessed event, Laura Dawson finds herself investigating why a young Berkeley student dropped out of school in the fall of 1880.

No one, including her friend Seth Timmons, thinks this is a good idea, since she is juggling a full course load with a part-time job, but she can’t let the question of what happened to her friend go unanswered. Not when it means that other young women might be in danger.

Maids of Misfortune, the first book in the series is permanently free.

Deadly Proof, the fourth book in the series, won first place in historical mystery category of the Chanticleer Mystery and Mayhem Awards last year (and is currently free as an ebook until June 6.)

Scholarly Pursuits, the sixth book in the series, like all the rest of the novels, novellas, and short stories set in Victorian San Francisco can be read as standalones.

All M Louisa Locke’s novels can be found at her website.

Many thanks Mary Lou. Wonderful essay. Deadly Proof sounds like yet another fascinating glimpse into early San Francisco history.

May 23, 2019

The History Girls: Labyrinths and initiations

My latest post on the History Girls delves into labyrinths and the secrets behind them. A millenia old construction that has been used for initiations and as a pathway to divine communion. Read more

April 23, 2019

History Girls: The Elusive Search for Dionysus

A common problem with authors who write novels set in pre-history is trying to deal with the ‘elasticity’ of sources from civilisations without extant written records. My latest post on History Girls is about my elusive search for the Etruscan Dionysus, and reaching across the ether to historians to help me.

March 29, 2019

A Research Odyssey by Lin Sten

I always enjoy meeting authors who are committed to authentically depicting their characters’ worlds and exploits. Lin Sten, a fellow ancient world afficionado, joins me today to explain some of the intricacies of his research for his Arion’s Odyssey tetralogy.

Imagining Classical Greece

Research for my tetralogy Arion’s Odyssey, set in Classical Greece, began haphazardly in my youth with my excitement over an image of an ancient Greek helmet; it continued as my interest in shipping and oared ships grew. As an adult, a significant step forward in my motivation to write a fictional tale, and do research for it, occurred in 1981 when Scientific American published a fascinating article about triremes (“Ancient Oared Warships”). Then, other creative projects (mostly film scripts and some poetry) interceded until 1998, during which I wrote a 160-page treatment for the tetralogy. After that, naturally my research became more focussed on the times, places, people, and events that had become the backdrop of Arion’s story (and that of Athens) from 445 BC to 427 BC.

The geography research was relatively easy, though one must take account of changes over the millennia. For example, the Aegean coast is now several miles away from the important seaport of ancient Ephesos due to twenty centuries of alluvial material, which forced closure of the ancient port facilities in the 1500’s; likewise, the narrow strip of beach at Thermopylai, valiantly defended by King Leonidas’ 300 Spartan hoplites against the Persians, is now much broader than it was in 480 BC. Similarly, for historic buildings: for example, the renowned Erechtheion (on Athens’ Akropolis) existed only on paper at the time of my story.

The geography research was relatively easy, though one must take account of changes over the millennia. For example, the Aegean coast is now several miles away from the important seaport of ancient Ephesos due to twenty centuries of alluvial material, which forced closure of the ancient port facilities in the 1500’s; likewise, the narrow strip of beach at Thermopylai, valiantly defended by King Leonidas’ 300 Spartan hoplites against the Persians, is now much broader than it was in 480 BC. Similarly, for historic buildings: for example, the renowned Erechtheion (on Athens’ Akropolis) existed only on paper at the time of my story.

While my research was guided and constrained by my desire to be as historically correct as possible, I also was committed to avoiding any premise of such significance that it would have been recorded given the level of detail in historical records of the time. The author of historical novels must make decisions about many historical things that have not been recorded; the constraints accepted above had to be reasonably intertwined with the fiction of my story, without seeming tedious in consideration of my impulse toward kaleidoscopic expansion in the details of Arion’s Odyssey.

Possibly the most interesting research challenge that I faced, due to the extent that navigation was central to much of Arion’s life, was in my being able to estimate how close to the wind a square-rigged ship could sail. This would affect how long a ship might take on any route, whether it would even set sail at all, or whether it could hope to evade a pirate ship. It was easy to make a decision about lateen rigging, for which the earliest artistic evidence I could find is from the second century AD, which is 600 years after the time of my story. On the other hand, I found it impossible to believe that, much earlier, experienced mariners wishing to steer close to the wind, would not have accidentally discovered the value of occasionally canting the yard of their rectangular sail toward the stem (by hauling forward and down on one brace, and loosing the other brace), thus converting to a canted trapezoidal rig (in which the lower clew would be switched to a more inboard position along the foot of the sail, thus rendering useless only a small triangular portion of the sail, and making the effective portion of the rectangular sail into a tilted trapezoid). This, and other ship issues, involved careful study of portions of ten books about ancient ships and navigation.

Egypt, the setting for a major portion of Volume 1 (Life After Death at Ipsambul), presented its own unique challenge because my Greek protagonist and his father were on a tour of Egypt with an Egyptian tour guide. What a tour guide in 439 BC might have known about Egypt’s architecture and (prior) history then, say, back to the time of Ramses II, would depend on who, if anyone, still read hieroglyphic writing then so that historical records could have been known then that in modern times were shrouded in mystery until Champollion began to succeed in his decipherment of hieroglyphic writing based partly on the Rosetta Stone, which had been discovered by an officer of Napoleon during his expedition to Egypt early in the nineteenth century.

Among the myriad details of Arion’s Odyssey research, equally interesting was learning that wealthy Athenians in summer time could chill their wine by adding snow from the deep ravines of Mt. Olympos. This bit of information affected only one line in a single volume of the tetralogy.

About Lin Sten

After leaving the aerospace industry in 1995, where he worked as an operations research analyst for nearly two decades, Lin Sten was able to give more attention to his passion for writing. In between film scripts, he wrote the nonfiction Souls, Slavery, and Survival in the Molenotech Age (Paragon House, 1999) and poetry. He completed a treatment for his historical tetralogy Arion’s Odyssey in 1998. After that, he wrote twelve drafts of Arion’s Odyssey between 2000 and 2007, and also wrote and published the Simple Sorcerer’s Illustrated Probability Primer in 2004. During a seven-year hiatus in work on the tetralogy, he wrote and published his science fiction novel Mine (2nd edition) between 2009 and 2011. He resumed work on Arion’s Odyssey in 2014, in conjunction with his editors and artists, and completed its publication in early 2018. He lives on the Pacific coast of the United States where he enjoys bodysurfing and snorkling.

Arion’s Odyssey tetralogy is available on Amazon : Life After Death at Ipsambul, Aegean Fire, Beyond the Battle of Naupaktos and Return to Lesbos.

Thanks Lin. I know all about researching a topic for months only to have the result appear in one sentence – or even end up on the cutting room floor.

On Inspiration: Interview with Leah Kaminsky

My guest today is Leah Kaminsky, an Australian physician and award-winning writer. Leah’s debut novel The Waiting Room won the prestigious Voss Literary Prize (Vintage Australia 2015, Harper Perennial US 2016). We’re all Going to Die has been described as ‘a joyful book about death’ (Harper Collins, 2016). She edited Writer MD (Knopf US, starred on Booklist) and co-authored Cracking the Code (Vintage 2015). Stitching Things Together was a finalist in the Anne Elder Award. The Hollow Bones is her most recent release (Vintage Australia 2019). She holds an MFA in Writing from Vermont College of Fine Arts.

My guest today is Leah Kaminsky, an Australian physician and award-winning writer. Leah’s debut novel The Waiting Room won the prestigious Voss Literary Prize (Vintage Australia 2015, Harper Perennial US 2016). We’re all Going to Die has been described as ‘a joyful book about death’ (Harper Collins, 2016). She edited Writer MD (Knopf US, starred on Booklist) and co-authored Cracking the Code (Vintage 2015). Stitching Things Together was a finalist in the Anne Elder Award. The Hollow Bones is her most recent release (Vintage Australia 2019). She holds an MFA in Writing from Vermont College of Fine Arts.

I was particularly interested to learn about Leah’s new book about SS Captain Ernst Schäfer’s Tibetan expedition given my own WIP deals with Nazi archaeologists who compromised their principles to subvert science and provide a justification for genocide. Their theories were bizarre and dangerous. Clearly Nazi zoologists were also involved in similar Faustian Bargains. The Hollow Bones sounds right up my ally!

You can connect with Leah via her website, Facebook, Twitter and Instagram. The Hollow Bones is available here.

What or who inspired you to first write? Which authors have influenced you?

I wrote my first poem in grade 3 (thanks Miss Elisabeth Weeks!) I loved reading as a child, and although I’ve always been pretty eclectic in my tastes, I devoured the classics. There are so many books that have stayed with me, long after I finished reading them. Some of my favourite contemporary authors are Anne Enright, David Grossman, Cormac McCarthy, Kazuo Ishiguro, Anne Michaels and Anthony Doerr. Australia has some fine writers, too many to name, but I’ve enjoyed recent books by Bram Presser, Melanie Cheng, Lee Kofman Alice Nelson, Tracy Sorenson and Emma Viskic.

What is the inspiration for your current book? Is there a particular theme you wished to explore?

I was drawn into the story of Ernst Schäfer, a young German zoologist and explorer, who rose up the ranks of the SS. When he was invited by Himmler to lead an expedition of German scientists to Tibet in 1938, on a whacky secret mission to explore the origins of the Aryan race, he struck a Faustian bargain in order to further his career. As a doctor with a background in science, the morality of scientists during wartime fascinates me and I felt a moral imperative to examine what happens when science gets into bed with politics.

I was drawn into the story of Ernst Schäfer, a young German zoologist and explorer, who rose up the ranks of the SS. When he was invited by Himmler to lead an expedition of German scientists to Tibet in 1938, on a whacky secret mission to explore the origins of the Aryan race, he struck a Faustian bargain in order to further his career. As a doctor with a background in science, the morality of scientists during wartime fascinates me and I felt a moral imperative to examine what happens when science gets into bed with politics.

What period of history particularly inspires or interests you? Why?

UK novelist Rachel Seiffert once tole me that ‘WWII is the war that keeps on giving.’ Although I tell myself that my next book won’t be thematically centred around the impact of war on ordinary people, I keep coming back to this era from different angles. I am the daughter of a Holocaust survivor, so I think I feel a moral imperative to bear witness to these events in my writing.

What resources do you use to research your book? How long did it take to finish the novel?

The Hollow Bones took 5 years to research and write. I read everything I could get my hands on about Tibet and Germany of the 1930s and painstakingly translated many documents such as letters and field diaries from the original German. I came across many of Schäfer’s papers and photographs in the library at the Academy of Natural Sciences in Philadelphia and was fortunate to gain access to film footage from the expedition. I was also shown hundreds of specimens brought back from Schäfer’s previous expeditions, including a juvenile panda he shot in 1932, which is now housed in the museum’s diorama. Panda became an important character in the novel.

What do you do if stuck for a word or a phrase?

If I can’t find a fresh way of writing about something, I turn to poetry. When I’m working on a specific project I always have a few volumes of my favourite poets scattered around my desk. Poetry distils the essence of things, and the language is fresh and often surprising. Poetry can describe something in a way you had never before considered. It takes my breath away when I discover the truth that words can hold.

Is there anything unusual or even quirky that you would like to share about your writing?

Although fiction and poetry are my truest love, I am ‘genre fluid’, and have written non-fiction books, essays, book reviews and newspaper articles. I love magic realism and often find touches of it creeping into my fiction, especially in The Hollow Bones.

Do you use a program like Scrivener to create your novel? Do you ever write in long hand?

I’m a technophobe by nature. I think I might be the last human to write the entire first draft of a novel in longhand. I have a favourite type of pen (black Classic Fine Bic) and a stack of recycled paper notebooks and I fill them with my scribbles. As I move forward I transcribe my draft onto a word document, editing as I type. It’s messy and cumbersome, but something magical lies in the process of writing directly onto the page

Is there a particular photo or piece of art that strikes a chord with you? Why?

This is a photo from the 1938 German Tibet expedition in which Ernst Schäfer is paying court to Tibetan dignitaries to try and curry favour so they will allow him to enter the holy city of Lhasa, which was off limits to foreigners back then. He has hung flags of the SS insignia and the swastika, telling his visitors that ‘East and West meet in the swastika’. This is one of hundreds of photographs that brought the expedition to life for me and helped me write The Hollow Bones.

This is a photo from the 1938 German Tibet expedition in which Ernst Schäfer is paying court to Tibetan dignitaries to try and curry favour so they will allow him to enter the holy city of Lhasa, which was off limits to foreigners back then. He has hung flags of the SS insignia and the swastika, telling his visitors that ‘East and West meet in the swastika’. This is one of hundreds of photographs that brought the expedition to life for me and helped me write The Hollow Bones.

I also love Yosl Bergner’s whimsical artwork in which everyday objects are infused with an eerie lifeforce.

What advice would you give an aspiring author?

Read. Read more. Read as much as you can. Devour books. This will help you find the rhythm and cadence of your own voice and feel how it sits within the rise and fall of literature. Writers are a chorus of observers, singing their own version of the world into words. Persist. Write for the love of language and its power to transform yourself, as well as others. Publishing is the business of writing; try not to let it blur the beautiful experience of watching words fall onto the page.

Tell us about your next book.

My next book will be published in 2020 and is a braided creative non-fiction work about an eccentric Yiddish poet, Melekh Ravitch, who came to Australia in 1933 to try and find a safe haven for German Jewish refugees. My father was friends with his son, Yosl Bergner, who went on to become a well-known painter and colleague of Albert Tucker and Arthur Boyd. It’s a strange historical tale. I’m working on another novel too, which is about dolls, but will keep that under wraps for now as the idea is not fully formed.

‘I remember you once told me about mockingbirds and their special talents for mimicry. They steal the songs from others, you said. I want to ask you this: how were our own songs stolen from us, the notes dispersed, while our faces were turned away?’

Berlin, 1936. Ernst Schäfer, a young, ambitious zoologist and keen hunter and collector, has come to the attention of Heinrich Himmler, who invites him to lead a group of SS scientists to the frozen mountains of Tibet. Their secret mission: to search for the origins of the Aryan race. Ernst has doubts initially, but soon seizes the opportunity to rise through the ranks of the Third Reich.

While Ernst prepares for the trip, he marries Herta, his childhood sweetheart. But Herta, a flautist who refuses to play from the songbook of womanhood and marriage under the Reich, grows increasingly suspicious of Ernst and his expedition.

When Ernst and his colleagues finally leave Germany in 1938, they realise the world has its eyes fixed on the horror they have left behind in their homeland.

A lyrical and poignant cautionary tale, The Hollow Bones brings to life one of the Nazi regime’s little-known villains through the eyes of the animals he destroyed and the wife he undermined in the name of science and cold ambition.

Thanks Leah – good luck with The Hollow Bones and your next project.

Haven’t subscribed yet to enter into giveaways from my guests? You’re not too late for the chance to win this month’s book if you subscribe to my Monthly Inspiration newsletter for giveaways and insights into history – both trivia and the serious stuff! In appreciation for subscribing, I’m offering an 80 page free short story Dying for Rome -Lucretia’s Tale.

Haven’t subscribed yet to enter into giveaways from my guests? You’re not too late for the chance to win this month’s book if you subscribe to my Monthly Inspiration newsletter for giveaways and insights into history – both trivia and the serious stuff! In appreciation for subscribing, I’m offering an 80 page free short story Dying for Rome -Lucretia’s Tale.

March 3, 2019

A Sweet and Bitter Time by GS Johnston

My guest today is Australian author, GS Johnston, author of The Skin of Water and The Cast of a Hand and Consumption, noted for their complex characters and well-researched settings. His new release is Sweet Bitter Cane, a beautifully rendered novel exploring an Italian woman’s hopeful emigration to an exotic but rigorous life in the Australian cane fields that leads to an unexpected need for survival when WW2 breaks out. Enjoy ‘A Sweet and Bitter Time’, his post on the background to writing his new novel.

In one form or another, Johnston has always written, at first composing music and lyrics. After completing a degree in pharmacy, a year in Italy re-ignited his passion for writing and he completed a Bachelor of Arts degree in English Literature. Feeling the need for a broader canvas, he started writing short stories and novels.

In one form or another, Johnston has always written, at first composing music and lyrics. After completing a degree in pharmacy, a year in Italy re-ignited his passion for writing and he completed a Bachelor of Arts degree in English Literature. Feeling the need for a broader canvas, he started writing short stories and novels.

You can learn more about GS Johnston and his books on his website, and he would love to connect with you via Facebook and Twitter.

Sweet Bitter Cane is available on Amazon. You can find all GS Johnston’s here.

A Sweet and Bitter Time

Writers are often asked where the first idea for a novel comes from, the question no doubt stirred by the vision of a writer hit by a lightning bolt, in a flurry of cats and dogs and paper and pens racing to the garret, and writing and writing, suffering, starving (me??), drowning in a sea of post-it notes until the novel is complete. I wish it was like that, but most of my novels have come from fractured and timorous trails, vague ideas simmering in the back of my mind for a very long time. Sweet Bitter Cane is a bittersweet case in point.

At twenty-eight, I had my first midlife crisis. The creative project I’d been working on had come to nothing. So intense was this work, I’d put off doing anything else. But now I just wanted to be secret and exult, run away for a little while. Even then Italy beckoned. I have absolutely no idea why beyond the food and … well … that combination of black hair, olive skin and blue eyes. Magic. And there was the promise of endless great coffee.

At twenty-eight, I had my first midlife crisis. The creative project I’d been working on had come to nothing. So intense was this work, I’d put off doing anything else. But now I just wanted to be secret and exult, run away for a little while. Even then Italy beckoned. I have absolutely no idea why beyond the food and … well … that combination of black hair, olive skin and blue eyes. Magic. And there was the promise of endless great coffee.

Before I left, I remember buying a small book, Give me Strength. Italian Australian Women Speak, published in 1989 by Woman’s Redress Press. I’ve no memory of how I found this book, probably a radio interview heard in the car in a traffic jam. But the book was a collection of recollections by women who’d migrated to Australia from Italy. These stories opened my eyes to so many tales, so much heartache and struggle. In comparison, my recent failure paled. But there was one story I remember of a family who migrated between the wars. Before the outbreak of WWII, they were living in Balmain, at that time a working-class suburb of Sydney, and had bought a small corner store, forging a small success.

In June 1940, when Italy entered WWII, the father was arrested, deemed by an indiscriminate broom to be an enemy alien for no apparent reason than he’d been born in Italy, sweeping all these men into Concentration Camps. Isolated and distant from their families, suspected of all manner of ill will to their new nation, the men were never asked of their affiliations. In this case, the family had left Italy before Mussolini’s rise to power.

It left the woman to run the business on her own. In a Balmain Kristallnacht, the shop windows were smashed. She tried, asserted herself, but eventually closed the shop and went to live with a relative who ran a market garden in Sydney’s outer hills district. But the business was destroyed, never recovered, hopes and dreams shattered on a flimsy pretext.

Occasionally I would hear or read other stories like these, and it would tickle this memory of the injustice and suffering. Often new information would come from the most oblique places, but once the antennae are alerted, perhaps they are the force guiding a writer’s attention, discerning and sorting. Little by little over thirty years, these bits of information turned and turned, gathering, a magnet and iron filings.

Occasionally I would hear or read other stories like these, and it would tickle this memory of the injustice and suffering. Often new information would come from the most oblique places, but once the antennae are alerted, perhaps they are the force guiding a writer’s attention, discerning and sorting. Little by little over thirty years, these bits of information turned and turned, gathering, a magnet and iron filings.

In 1901, Italians were invited to work on the cane fields of Far North Queensland. They suffered great hostility from the British Australians, especially from the workers’ unions, compounded when Italians afforded to buy lots of land. Soon accusations circulated that the Italians were sending money back to Italy, so it was only a small step to accuse them of being pro-fascist, and as a consequence pro-Japanese, despite the fact most of these people had left Italy before the 1921 rise of Mussolini. Kind of sounds familiar…?

But the Italian consulate in Australia did a great job of disseminating pro-fascist propaganda. To be fair, when the workers’ unions made it difficult for Italian cane cutters to be employed, the Italian consulate offered help. And the letters these people received from friends and family in Italy would only have dared to be positive. So, from the beginning, I had a feeling the Italians in Australia had a rather distorted view of what was going on in Italy, what fascism was, (fascio is a bundle, bunch or sheath) and consequently saw Mussolini as the saviour, only hearing of his great reconstruction of Italy after WWI.

But whilst the arrests of the men were the main injustice, the tragedy lay with the women and families. These stories interested me more. But when I finally started researching, I met the usual barrier – history was written from a male perspective. Most of the research, even the most current written by women, focused on men, and young men at that.

In the research, there were many fortunate moments, none more so than being given a folder of documents pertaining to the fate of an Italian woman, Gina Omodei. Her daughter lived next door to me – who would have thought? – odd what can happen when you talk to a neighbour. In a very fractured way, these documents told of the events after Gina’s husband’s arrest. Considering the temper of the times, some of her actions were perhaps a little naïve, but even so, no-one deserved what happened.

In the research, there were many fortunate moments, none more so than being given a folder of documents pertaining to the fate of an Italian woman, Gina Omodei. Her daughter lived next door to me – who would have thought? – odd what can happen when you talk to a neighbour. In a very fractured way, these documents told of the events after Gina’s husband’s arrest. Considering the temper of the times, some of her actions were perhaps a little naïve, but even so, no-one deserved what happened.

As the real Gina mutated into my character, the hybrid Amelia, the first piece I wrote was based on one of the documents, a thinly-veiled interrogation of Gina after her husband’s arrest. She was fearful what more could happen. A number of times, the report described her as a shrewd woman and that care needed to be taken. Gina was an intelligent woman, perhaps a threat. But under all this, I felt rather than this woman being accused of fascist support, old grudges were unfolding and these were the greater reasons for the arrests.

And so I started work on the novel, the untold story of a woman in this turbulent, sweet and bitter time.

One woman. Two men. A war.

Twenty-year-old Amelia marries Italo, a man she’s never met. To escape an Italy reeling from the Great War, she sails to him in Far North Queensland to farm sugarcane. But before she meets her husband, she’s thrown into the path of Fergus, a man who’ll mark the rest of her life.

Faced with a lack of English and hostility from established cane growers, caught between warring unions and fascists, Amelia’s steady hand grows Italo’s business to great success, only for old grudges to break into new revenge. She is tested by forces she couldn’t foresee and must face her greatest challenge: learning to live again.

Sweeping in its outlook, Sweet Bitter Cane is a family saga but also an untold story of migrant women – intelligent, courageous and enduring women who were the backbone of the sugarcane industry and who deserve to be remembered.

Haven’t subscribed yet to enter into giveaways from my guests? You’re not too late for the chance to win this month’s book if you subscribe to my Monthly Inspiration newsletter for giveaways and insights into history – both trivia and the serious stuff! In appreciation for subscribing, I’m offering an 80 page free short story Dying for Rome -Lucretia’s Tale.

Haven’t subscribed yet to enter into giveaways from my guests? You’re not too late for the chance to win this month’s book if you subscribe to my Monthly Inspiration newsletter for giveaways and insights into history – both trivia and the serious stuff! In appreciation for subscribing, I’m offering an 80 page free short story Dying for Rome -Lucretia’s Tale.

February 23, 2019

History Girls: The Secret Garden: Contraceptives in the Ancient World

My latest essay on the History Girls explores the natural remedies used in the ancient world for contraception including a garden fruit, and a mysterious plant from a distant land. The Secret Garden: Ancient World Contraception.