Beverly Gray's Blog: Beverly in Movieland, page 47

April 23, 2021

Up the Rebels! -- Fred Hampton, Abbie Hoffman, and the Oscar Powers-That-Be

I watched Judas and the Black Messiah on a day fraught with longterm implications: a Minneapolis jury had just convicted ex-police officer Derek Chauvin for the murder of George Floyd. Given that the number of unarmed African-Americans killed by cops in the name of law and order continues to rise, I could certainly understand the stone-cold cold fury with which the film’s Fred Hampton, chairman of the Chicago branch of the Black Panther Party, spoke out against white authority figures of all stripes. By the same token, when Hampton’s character (as played by Daniel Kaluuya) announced his determination to overthrow the U.S. government, all I could think of was the January 6 assault on our Capitol by a very different set of dissidents with a very different agenda. How times have (and have not) changed!

Although the true-life incidents that make up Judas and the Black Messiah take place in 1968, the story seems more than timely today. Sure, J. Edgar Hoover (played, ironically enough, by classic good-hearted liberal Martin Sheen) no longer heads the FBI, and Hoover’s deeply entrenched racism is perhaps no longer official policy. But current events have shown there’s no shortage of bias against Black and brown communities, and I’m grateful to this film for its perspective on a key slice of American history. I’m also grateful for two razor-sharp performances, both of them nominated for the Best Supporting Actor Oscar, much to the annoyance of critics who wonder why neither portrayal was judged to be a leading role. As Fred Hampton, Kaluuya (best known in this country for Get Out) crackles with charisma, alternating between eloquent anger and the tender regard he shows for his woman and his unborn child. The real Hampton was only 21 when he died, and it’s a shame we’ll never know how he might have evolved.

The film’s second nominated Best Supporting Actor, the “Judas” of its title, is Lakeith Stanfield, playing Bill O’Neal, the crafty Chicago car thief “persuaded” by the FBI to infiltrate the Black Panthers. Stanfield, coming off a long string of credits in major films (Uncut Gems, Knives Out) has perhaps the bigger acting challenge. His character is that of a man who keeps his feelings close to the vest, one whose ultimate fate – as spelled out in the film’s final moments – can in fact be read several ways. Stanfield plays the enigma forcefully, allowing viewers to make up their own minds.

Despite these golden performances, and some brilliant crowd moments, Judas and the Black Messiah can be baffling at times. But it makes a fascinating comparison to another big Oscar nominee, set in the same era and the same locale. The Trial of the Chicago 7, which zeroes in on a motley group of young activists arrested following the 1968 Democratic presidential convention, has been justly honored as a terrific ensemble piece, with such fine actors as Frank Langella, Mark Rylance, John Carroll Lynch, and Eddie Redmayne all doing their part. But the one actor from the film singled out for an Oscar is the ubiquitous Sacha Baron Cohen, who for years had coveted the role of activist clown-prince Abbie Hoffman. Though I once thought of Baron Cohen as a goofball, I’m now convinced he’s a highly serious and morally indignant man, a perfect choice for the kidding-on-the-square role of the Yippie leader. He’s also having a banner year, with his Borat sequel far more politically pointed than its predecessor. Can he wrest the Oscar from Kaluuya and Stanfield? We’ll soon find out.

April 20, 2021

Saying “Skoal!” to “Another Round”

Danes of my acquaintance proudly note a global survey ranking them as the happiest nation on earth. (They were less happy during my 2017 visit, because they’d been beaten out of the top spot on this annual survey by their Norwegian neighbors.) Having just seen Thomas Vinterberg’s Oscar-nominated Another Round, I’m now wondering whether all that Danish happiness stems from the fact that Danes go through life half-sloshed.

Or so it appears from Vinterberg’s film, which corroborates some rather alarming statistics about drinking among Danish teens. Another Round opens with cheery pop music playing as a group of wholesome-looking Danish youth participate in something called the Lake Run. Teams of young people dash around a lake, following rules that have them chugging bottles of beer at regular intervals, ending up with a crate full of empties. It’s played like good clean fun, even when some of the contestants upchuck. No harm done: when it’s over, everyone celebrates, then moves on.

But Another Round is not really about teenagers. Its focus is on four middle-aged men who are teachers at a local Danish high school. When we first meet them, they’ve gathered in a posh restaurant for the celebration of a fortieth birthday. Two of the men are single, at least one unhappily so. The birthday boy, a science teacher, is chafing under the pressure of a home life that includes three very young children, all seemingly inclined to pee in his bed. Then there’s the longtime history teacher, Martin, who’s played by Vinterberg favorite Mads Mikkelsen. Once an academic firebrand with a yen for modern dance, he’s now settled into a morose existence both in the classroom and at home. His wife balefully admits he is no longer the vibrant young man she married.

At that pivotal birthday party, one of the men presents the half-baked theory of a Norwegian scholar that human beings need the constant presence of alcohol in their systems for maximum efficiency. Thus begins an experiment in secret daily drinking, one with profoundly mixed results. On the one hand, Martin and the others feel more invigorated, more creative, more attractive. Scenes of the four men together show them re-discovering the joie de vie of their youthful selves, frolicking through the city without stodgy inhibitions. They’re also more dynamic in their classrooms, and Martin’s domestic life perks up when he takes the family on a camping vacation.

Inevitably, though, problems creep into their happy new lives. Marriages wobble, school administrators get wind of their misbehavior, and one of the four teachers comes to a crossroad that ends tragically. Lesson learned, right? The experiment stops abruptly, and everyone lives happily ever after?

Perhaps the most memorable part of this film is its ending, with teachers and students out by the harbor, celebrating graduation day. The kids are happily passing around the brewskis, looking forward to their future lives. They hail their teachers (still in pallbearer garb) as heroes and pals, urging them to drink up. It’s at this point that Martin—on the brink of making amends in his marital life—turns into the life of the party. With no prompting from anyone, he suddenly goes into a wild exhibition of jazz dance, culminating with an exuberant leap toward the bay below. Freeze frame. He’s half celebrating, half drowning, and this film is honest enough to see both possibilities. Hollywood has treated alcohol (in such films as The Lost Weekend and The Days of Wine and Roses) as a dangerous drug. Vinterberg sees the same thing, but is honest enough to show the other side as well.

April 13, 2021

Larry McMurtry’s First Picture Show

In homage to the late Larry McMurtry, chronicler of the American West in all its complexity, I’ve been watching movies made from his work. There’s a whole slew of those, including Oscar winners Terms of Endearment and Brokeback Mountain. The very first was Hud (1963), adapted from a McMurtry novel. But The Last Picture Show (1971) was the first film (though not the last) for which McMurtry provided a screenplay, working with director Peter Bogdanovich to transform his own prose fiction for the screen.

By the time he made The Last Picture Show, Bogdanovich was a veteran of Roger Corman’s B-movie world, responsible for the macabre thriller, Targets. But The Last Picture Show was his leap into the bigtime, and he made the most of it, turning out a moody tribute to a dying Texas town and its lonely, love-starved denizens. The opportunity to participate must have thrilled McMurtry, who was known to lament in later years that “Movies have largely lost interest in character. It is not without significance that two of the most publicized characters in the cinema have been a shark and a mechanical ape.”

The Last Picture Show, filmed in evocative black & white, mostly in the tiny Texas town where McMurtry grew up, is all about character. In contrast to the year’s big Oscar winner, The French Connection, it moves forward slowly, exploring the intricate relationships of the town’s citizens, who are played by some of Hollywood’s finest actors. Cloris Leachman won an Oscar for her poignant role as a neglected housewife; other acting nominees for this film included a young Jeff Bridges (as the hero’s laid-back buddy) and Ellen Burstyn as a mother who sees her daughter’s character flaws—and her own—with all too much clarity. For Randy Quaid, in the small but sharply observed role of a well-to-do high school kid, it was the start of a major Hollywood career.

And of course The Last Picture Show marked the cinematic debut of model Cybill Shepherd, who plays Jacy Squires. Shepherd’s blonde beauty is electric on screen, and in one sense the entire town is shown to revolve around her haughty sense of sexual entitlement. But there’s a sad footnote to her presence in the film. Bogdanovich was apparently as bedazzled as his cast of characters. By the end of the shoot, he and Shepherd were together, leaving his wife and longtime artistic partner Polly Platt out in the cold. The multi-talented Polly, whom I was fortunate to interview at length in 2008, eventually recouped and went on to have a major Hollywood career of her own. But this film marked the end of the strong husband-and-wife collaboration that had seen them through their Corman years.

The Last Picture Show was nominated for a total of eight Oscars, including Best Picture. Aside from Leachman’s win, the only other Oscar for the film was taken home by Ben Johnson, in the small but commanding role of the town’s moral conscience, known as Sam the Lion. The story is that he had to be persuaded by his mentor, John Ford, to accept the part. He was sought after by Bogdanovich, a true student of cinema history, partly because of his association (as stuntman and actor) with Ford and John Wayne, whose sidekick he often played. The Last Picture Show draws to a close with a final screening at the town’s one cinema. The movie on the screen is the 1948 classic western, Red River. This film, as well as Ben Johnson’s casting, represents a fond look back at the glory days of the silver screen.

April 9, 2021

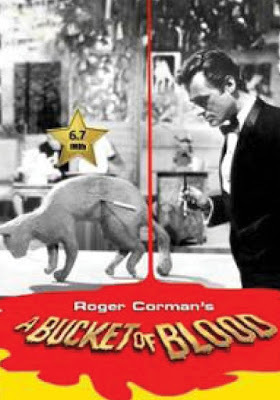

Life as an Obscure Hobo in “A Bucket of Blood”

In Roger Corman’s birthday week, it seems right to focus on the master, now 95, and some of his most memorable achievements. Like the horror comedies written by the irrepressible Chuck Griffith and ground out by Roger in a few days on impossibly low budgets. A few weeks ago I was interviewed at length by a scholarly type with the wonderfully biblical name of Adam Abraham, who’s writing a book on the history of The Little Shop of Horrors. His fascination with the film began when he encountered Howard Ashman and Alan Menken’s masterful transfiguration of the 72-minute black-&-white flick into a sparkling stage musical that began Off-Broadway and is doubtless playing somewhere in the world at this very moment. (Eventually, of course, it became a splashy full-color all-star 1986 movie musical that lacked the original’s mordant charm. And now there’s talk of a remake.)

Adam is convinced that the original Little Shop remains in the public imagination today mostly because of the transformative skill of Ashman and Menken’s work. I’m not so sure. Clearly the stage musical brought new fans to the 1960 Corman flick. My Roger Corman: Blood-Sucking Vampires, Flesh-Eating Cockroaches, and Driller Killers traces how Roger – cashing in on the play’s success -- eventually made a nice bundle off a three-day production he had not even bothered to copyright. Still, Jonathan Haze, Jackie Joseph, Mel Welles, and company are still fondly remembered by B-movie aficionados everywhere.

Still, I believe that Roger and Chuck’s earlier effort, 1959’s A Bucket of Blood, is the better, smarter black comedy. If you like morbid satire, this film’s for you. Running a tight 66 minutes, it boldly pokes fun at the high seriousness of beatnik culture, in which bearded and beret-wearing hipsters sit around in coffee houses pontificating on the meaning of life. Its hero, of sorts, is the coffee-house busboy, a young loser who wants so badly to be admired for his artistic talent that he eventually resorts to mayhem. This poor shnook, a would-be sculptor named Walter Paisley, is played by the always memorable Dick Miller with such intensity that the film isn’t easy to dismiss – like Little Shop -- as outrageous fun. No wacky man-eating plant here, just a deeply flawed character making the wrong choices and (almost) finding himself rewarded for getting away with murder. (Dick was originally offered by Roger the lead role in Little Shop, but turned it down because he didn’t want to be typecast as a schlemiel; he appears instead as a flower-shop patron, the petal-munching Burson Fouch.)

Even in its own day, A Bucket of Blood seemed darker, more real, and less laughably goofy than Little Shop. That, I suspect, is why Howard Ashman, who had grown up with Corman’s horror comedies, turned to Little Shop as material for his first really big outing as a theatre lyricist, librettist, and director. Still, A Bucket of Blood has also had a bit of an afterlife. In 1996, as part of a TV outing called Roger Corman Presents, Anthony Michael Hall starred in an updated version that found a place for lots more blood and nudity, as well as cameos by such comic favorites as Will Farrell. In 2009 an enterprising Chicago team hoping to be the next Ashman and Menken launched Bucket of Blood: The Original Beatnik Musical. (Nothing seems to remain of it but a nifty website, which includes lively recordings of some of the score.) And for the rest of Dick Miller’s life, he was cast by famous Corman alumni as characters affectionately named Walter Paisley. Even, ultimately, Rabbi Walter Paisley.

April 6, 2021

Beyond “Battle Beyond the Stars”: Roger Corman Makes His Own Cheapie “Star Wars”

The original edition of my biography of my former boss Roger Corman, which appeared in 2000, called him on its cover “the godfather of indie filmmaking.” He was then 74 years young. Yesterday, on April 5, 2021, he turned 95. And he’s still at it, producing and distributing low-budget flicks. He’s still the godfather, but also something of an ancient mariner, plying the rough seas of today’s entertainment industry.

I’ve just happened upon a relic of one of Roger’s most productive periods at New World Pictures. Emmy-winning film editor Allan Holzman, credited with editing the ambitious 1980 Corman space epic Battle Beyond the Stars, kept a diary throughout the five-week shoot of a film that Roger later grandly claimed was two years in the making, at the cost of $4 million. Now Allan has assembled what he calls “Celluloid Wars: Lessons Learned From Making the Movie Battle Beyond the Stars.” This as-yet-unpublished volume offers a trove of images and sketches from the film’s production period, along with such bonus features as Allan’s after-the-fact interview with SFX wizards Robert and Dennis Skotak, regarding its cheap but nifty visuals.

But the heart of the book is Allan’s running account of the day-to-day challenges faced by Corman minions as they struggled to do the impossible, turning out a credible “Magnificent Seven in Space” in time to beat The Empire Strikes Back into theatres. They overcame every possible obstacle: a director who’d never before worked in live-action cinema; some newbie actresses (to go along with seasoned veterans like Robert Vaughn and Richard Thomas); a lumber-yard-turned-studio with a leaky roof; questionable equipment; and Roger’s own mercurial temperament. One personal victory for Allan came after he’d spotted a dejected young worker whose long labors on a series of front-projection slides of faraway galaxies were wasted because they’d come out too dark to be of any use. Once Allan recognized the beauty of these images, he alerted Roger that perhaps the young artist had a future in set design. So James Cameron was promptly promoted to art director, and the rest is cinema history.

Partly I love this book because it includes so many people with whom I too have worked. It also gives a fascinating editor’s-eye view of how a production staff interacts with the Corman front office, speculating in a way I find extremely credible on why Roger prefers to surround himself with yes-women. But above all this book teaches the reader what a film editor is, and how his mind works. He describes himself unsparingly: “I’m a hermit and a voyeur.” He’s frank about how, as an AFI graduate, he worked his way into editing partly because—as a lifelong stutterer—he found in this particular job a way to sidestep his own physical challenges, as well as a chance to indulge his perfectionist instincts. At times he reveals his frustration with the rest of crew: “They probably just think I’m an uptight asshole who can’t mellow out and give in to the fact that at New World Pictures, sloppiness is our most dependable product. Sorry for the putdown, Roger, but it’s true.” But he also makes clear his love for the exacting process of trying to spin straw into cinematic gold. He writes at one point: “I wish people would stop thinking editors just put things together by taking out the waste or tightening things up. We mold and manipulate as we wend a tale through the existing footage in such a way that the overall movement of a scene is equal to the underlying emotion.”

Bravo, Allan. And happy birthday, Roger!

April 2, 2021

Calling All Fans of "Call My Agent!"

It was my own agent (Hi, Stuart!) who first turned me on to Call My Agent!. This French series originally titled Dix Pour Cent (or Ten Percent), was spread over four seasons, beginning in 2015. Which means its memorable stars have by now all moved onto other projects. When I get to the end I’ll certainly miss them.

The series explores day-to-day life in a talent agency, where starry clients are the norm. The brilliant title sequence begins with a young woman in full eighteenth-century aristocratic attire. She seems to belong at the court of some King Louis, until we watch her beautifully shod foot step over a series of wires and cables. At which point we know we’re on a movie set . . . and before long the same filleis striding out the door, clad in sneakers and tight jeans.

Part of the fun of Call My Agent! is that it features real-life celebrities who seem to be having a ball playing slightly ungainly versions of themselves. They’re always in crisis mode: two old-school performers are in the midst of a longtime feud; an up-and-comer slated to star in a road movie has panic attacks when behind the wheel; a well-known twosome break up just before they’re scheduled to shoot a film that will tap their romantic chemistry. An American viewer can’t fully appreciate these unfamiliar French vedettes, but as the series wears on it presents some names well known on this side of the Atlantic. One example: Juliette Binoche, who in the second-season finale appears as the celebrity host of the Cannes Film Festival. Not only is Binoche trying to elude a stalker but she’s also forced to make her big welcome speech while wearing a hideously poufy designer gown. I won’t soon forget her desperate sprint to locate the ladies’ room behind the scenes in the cavernous Palais.

Though the warts-and-all French celebrities are charming, the series’ focal figures are in fact their representatives, who’ll do (just about) anything to further their clients’ screen careers. The jostling among them is sometimes reminiscent of Mad Men, though this is hardly a period piece reflecting a bygone era. People of color play some of the featured roles, and one of the agents—the uber-passionate Andréa—is unabashedly gay. She’s a vivid presence, as is the fashionably scruffy Gabriel (who perhaps unwisely gives his heart to a fledgling actress), and the dapper Matthias, whose personal secrets come to the fore over the course of seasons 1 and 2. But the audience favorite may be wide-eyed young Camille, the diligent assistant whose journey into the business of agenting we follow over the course of the series. Is she the Peggy Olson of Call My Agent? Not exactly, but I look forward to following her trajectory in seasons 3 and 4.

There was a time when episodes of a mostly comedic TV series could be viewed in any order, since (during a season, at least) no big transformative changes took place. But in Call My Agent!, as in so many of today’s series, there is a constant unfolding of events that change everything. I’ll avoid any big reveals, so as not to spoil the fun, but do expect a glimpse of the softer side of Andréa, and wait for the moment when the starchy Matthias melts into a puddle of deep emotion. Minor players too are full of surprises.

Call My Agent! is a terrific way to improve your grasp of colloquial French. Thank goodness, though, for subtitles.

March 30, 2021

The March of Time: Losing Larry McMurtry and Beverly Cleary

Movies set under western skies go back to The Great Train Robbery¸ which mesmerized viewers in 1903. Unlike many in my generation, I didn’t grow up obsessed with cowboys-and-Indians flicks. But I learned early on that films that call upon our collective vision of the rugged western states can have a lot to say about our lives here and now. John Ford’s 1939 Stagecoach conveyed some important lessons about the relationship of the individual and the community. William Wellman’s The Ox-Bow Incident (1942) powerfully explored social justice and the mentality of a lynch mob. In 1952, Fred Zinnemann’s High Noon focused on the courage to stand alone, even when times are tough. A decade later, Lonely Are The Brave featured Kirk Douglas as a cowboy who can’t find a way to adjust to the modern world.

Westerns tend to go in and out of fashion. Though the early career of Clint Eastwood was heavily dependent on Old West sagas (notably the wild-and-wooly spaghetti westerns of Sergio Leone), the name I most associate with westerns of all stripes is writer Larry McMurtry, who left us March 25 at the age of 84. McMurtry, who was born and died a Texan, loved chronicling his native soil in novels and screenplays that displayed a wide range. His 1962 novel Horseman, Pass By became an Oscar-winning 1963 film, Hud, about the hard-scrabble life on a cattle ranch. In 1971, he adapted his own The Last Picture Show, bringing to the screen an indelible portrait of a dying Texas town and its people. Once again actors (Cloris Leachman, Ben Johnson) took home trophies for conveying the joys and constraints of western living.

McMurtry’s most enduring gift to television was Lonesome Dove, a Pulitzer-winning 1985 novel that became a four-part mini-series starring Robert Duvall and Tommy Lee Jones as two former Texas Rangers who join a cattle drive. Its wild popularity among viewers and critics alike resuscitated the western genre, and led to a TV series as well as other spinoffs. But McMurtry received his highest Hollywood accolades for helping to adapt the writing of someone else. In 2005, he and longtime collaborator Diana Ossana won Oscars for turning a very short, very spare story by Annie Proulx into a landmark film, Brokeback Mountain. Their sensitive depiction of two gay cowboys in the modern west prompted impassioned national conversation about gender roles and machismo in today’s society.

Even in death McMurtry will surely be much discussed. Terms of Endearment, the 1983 hit film that won Shirley MacLaine her Oscar, is currently being remade by Lee Daniels, with Oprah Winfrey in the role of a Houston mom with a dying daughter. It’s based on yet another McMurtry novel, one without cowboys (though it does have a memorable astronaut character, played in 1983 by Jack Nicholson, who – yes – also walked off with a gold statuette). No question that McMurtry loved the movies, and they love him right back.

Also on March 25 we lost another great writer. Beverly Cleary was known for Beezus and Ramona, Runaway Ralph and other books for young readers. Her warm-hearted stories of middle-class kids are fun to read, but also seem to reflect the daily lives of genuine kids. Having a pesky younger sister of my own, I was sure that Cleary had grown up in a household much like mine. In fact, she was an only child struggling to survive an emotionally damaged mother and other serious challenges. But talent will out, I guess. Cleary, who lived to be 104, clearly came to appreciate happy families and their often-hilarious interactions.

March 26, 2021

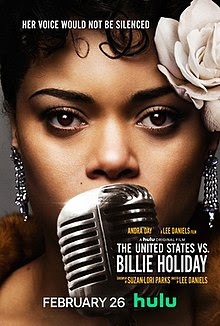

Biopics: Hailing Two Great Ladies of Song

Hollywood always seems ready to launch another biopic. In the early days of talkies, studios rushed to immortalize famous men on film, resulting in the fawning treatment of such historical figures as Sam Houston, Abraham Lincoln, and waltz king Johann Strauss. Accuracy was not exactly the goal: a 1929 flick starring George Arliss made a long-ago prime minister of Great Britain sound like an action hero: “Benjamin Disraeli outwits the subterfuge of the Russians and chicanery at home in order to secure the purchase of the Suez Canal.” As the decades wore on, America’s top actors vied to play high-achievers whose lives were picturesquely tortured. Kirk Douglas, portraying Vincent Van Gogh in the 1956 biopic, Lust for Life, was honored with an Oscar nomination. And Anthony Quinn, as Van Gogh’s frenemy, Paul Gauguin, went home with a Supporting Actor statuette for the same film.

Which suggests there’s gold to be gained by playing a real historical figure with a compelling life story. Like Helen Keller and her teacher Annie Sullivan: both Patty Duke and Anne Bancroft (yes, Mrs. Robinson herself) won Oscars for their roles. More recently, biopics of major entertainment figures like Richie Valens (La Bamba, with Lou Diamond Phillips), Jim Morrison (The Doors, with Val Kilmer), and Ray Charles (Ray, an Oscar-winning role for Jamie Foxx) have heaped accolades on actors while reminding us of the huge talents we have lost.

Just two years ago, Rami Malek nabbed an Oscar for his flamboyant portrayal of Queen’s Freddie Mercury in Bohemian Rhapsody. Not long thereafter, another gay rocker, Elton John, was vividly portrayed by Taron Egerton in Rocketman. These things go in cycles: now it seems to be the turn of African-American musical divas with complex family histories.

Of course I’m thinking about this year’s The United States vs. Billie Holiday, for which singer/songwriter Andra Day has already picked up a Best Actress Golden Globe. She’s also now an Oscar contender for this role. It’s a powerhouse performance, one that asks her to approximate Holiday’s unique singing style while also conveying the lady’s painful life. This is hardly the first time Holiday has been portrayed on the big screen: back in 1972, Diana Ross starred in Lady Sings the Blues, for which she too earned an Oscar nom. (In that same landmark year for Black women, Cicely Tyson was nominated for Sounder, but both lost to Liza Minnelli’s iconic performance in Cabaret). The focus for Ross’s portrayal was on Billie Holiday’s heroin addiction. This year’s film, by contrast, tells the fascinating true story of how J. Edgar Hoover’s FBI went after Holiday (even sending a young Black agent to pose as a super-fan) because of the political implications of her show-stopping ballad, “Strange Fruit.” It’s a tale worth telling, but director Lee Daniels, never known for subtlety, crams the screen with intertwining subplots, so that we’re never entirely certain who’s doing what to whom.

While Andra Day is lighting up the screens of whatever movie houses are open these days, the talented Cynthia Erivo is portraying Aretha Franklin in a multi-part segment of the cable-TV series called Genius. Less glamorous than Billie Holiday, Franklin lived a life that had its own challenges, including a domineering father who was a superstar preacher. I saw the first episode, which introduced us to the child who grew up to be the Queen of Soul as well as the young woman whose grasp of how she wanted to sing was already secure. And an Aretha biopic starring Jennifer Hudson is on its way to the multiplexes this summer. Genius indeed!

.

March 23, 2021

Minari: The Family That Grows Together . . .

We’re all too aware that this is a tough time to be an Asian American. Last week’s shooting at three Atlanta massage parlors took the lives of eight people, six of them Asian-American women. Elsewhere in the U.S., there’s been a spate of street attacks on elderly folks who have the bad luck to have Asian-looking faces. Alas, their ancestry makes them ripe for being blamed for introducing the COVID-19 virus, which seems to have begun in Wuhan, China.

Here’s the irony: at the same time that many Asian-Americans are cowering in fear, the American film community has bestowed a bumper crop of awards nominations on Asian-American projects. Beijing-born Chloé Zhao, who’s quickly becoming one of the foremost chroniclers of the American West, has been personally nominated for four Oscars as producer, director, writer, and editor of Nomadland. Riz Ahmed, whose Pakistani birth makes him officially Southeast Asian, is up for Best Actor for his role in the engrossing Sound of Metal. And, of course, one of the eight Best Picture nominees is a true immigrant story, based on the life of an Korean family not far removed from the filmmaker’s own.

Minari is a small, modest film, which in most non-COVID years may have been better suited to the Indie Spirit awards than the Oscars. (This year it’s up for six of each.) Like Nomadland, it’s a labor of love on the part of a rising filmmaker who both wrote and directed. But Lee Isaac Chung, a Korean immigrants’ son who was raised on a small farm in rural Arkansas, shaped an original story out of something close to his own family experience. The foursome in the film—father Jacob, mother Monica, daughter Anne, and the adorable little David—hunker down in a mobile home on a small, untamed plot of land because Jacob (eager to leave behind his dispiriting California life as a chicken sexer) can’t wait to work the soil. His wife is less than pleased by their lonely, somewhat grubby new existence, especially since young David has heart issues that could end his life at any moment. The arrival of Monica’s fresh-off-the-boat mother, the feisty and unpredictable Soonja (in an Oscar-worthy performance by Korean star Youn Yuh-Jung), complicates matters further. Clearly, something explosive is about to happen.

Happily, given the times in which we live, the family is not done in by racism. The locals (at church and elsewhere) are quick to show off their ignorance of Korea, but they never stoop to cruelty. And a holy-roller type whose impromptu religious rituals make him an object of derision in this locale becomes something of a true friend.

Those who disdain reading subtitles will not be fans of Minari. In a nod to authenticity, a vast amount of the family interaction is conducted in Korean, with an American phrase thrown in from time to time as immigrants are wont to do. When family members communicate with the outside world, they manage in English, but the Korean language predominates. That’s partly why the Golden Globes folks, never known for being socially progressive, put Minari in their Best Foreign Language Film category, which it handily won. Given that the U.S. is a country of many languages and cultures, it would have been nice to see this film included as one of the evening’s top “bests,” but never mind.

By the way, the all-important “minari” turns out to be water celery or Java waterdropwart. I have no idea what that is, but in future I’ll look at the Korean vegetables at my local farmer’s market with new respect.

March 19, 2021

Nomadland: On the Road Again

At a time of lockdown, the allure of Nomadland seems particularly potent. While many of us are stuck at home, consigned to staying within our own familiar ruts, the characters in this quietly magical film keep on trucking. Partly it’s a matter of economic distress, but mostly it’s a choice: these are people who frankly love the romance of the open road. And the Oscar-nominated cinematography of Joshua James Richards (one of six nominations garnered by Nomadland this past week) captures the landscape of the American west so gorgeously that afterwards I wanted to pack up and set out for Arizona or the South Dakota badlands. Maybe it takes a foreigner like the Beijing-born director Chloé Zhao to teach us to look with new appreciation at our own land.

But the film is more than a travelogue. Director Zhao has a clear passion for cinéma verité. Here, as in her acclaimed earlier film, The Rider, she incorporates in central roles the people—non-actors—who are really living the tale she wants to tell. This means that such just-plain-folks as Linda May, the charismatic Bob Wells, and the feisty, dauntless Swankie appear as (presumably) the van-dwelling travelers they really are. And the film’s lead actors, including the much-honored Frances McDormand and David Strathairn, pitch their performances to match the everyday rhythms of the non-pros, convincing us that they too are part of this special world.

For a while, in watching this film, you’ll find yourself expecting some big drama to burst onto the screen. We’re so conditioned to appreciate movies full of blood and guts that we’re waiting for impending disaster: a rapist on the loose, a disastrous accident, a crippling loss. As we eventually discover, the undulations here are so much more subtle than the big crescendos of most Hollywood movies. McDormand’s Fern, whom we first meet as she’s signing in for a shift at an Amazon warehouse, has long since adapted to life on the road. The big events of her time on earth--her leaving the family home, her long marriage, the loss of her husband and of the mining community that once sustained them both—have all occurred long in the past, and she’s made her peace with the lifestyle of a wanderer, traveling the back roads in a rickety old van that doubles as her home. It’s a life that she (mostly) finds emotionally sustaining, full of peripatetic friendships, a variety of odd jobs, and wide open spaces tantalizing in their beauty. So attached is she to this vagabond way of life that she can’t be tempted by a comfy bed in the home of an hospitable friend. No, she’s got to keep shoving on.

Which is not to say that she’s always happy. Aside from the daily challenges of life on the road, Fern is quietly facing her past and her future. A dying road buddy is a reminder that she won’t always have the capacity to survive on her own. And, though it takes us a while to fully recognize it, the loss of her husband and of the house they shared for so many years is not something that her chipper attitude toward the world can fully mask. It’s a subtle performance, but one of McDormand’s best, indicative of her ability to disappear into salt-of-the-earth roles that make this extraordinary actress seem wholly average.

I’ve just discovered McDormand will soon appear as Lady Macbeth, opposite Denzel Washington, in a film directed by her husband, Joel Coen. Macbeth’s blood-thirsty lady is hardly the salt-of-the-earth type, and I can’t wait to see the results.

Beverly in Movieland

- Beverly Gray's profile

- 10 followers