Beverly Gray's Blog: Beverly in Movieland, page 43

September 10, 2021

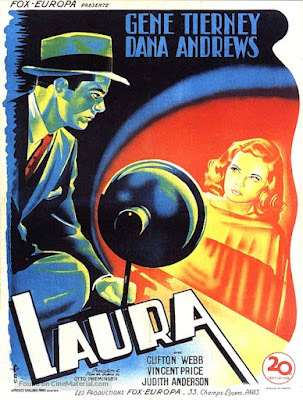

The Several Faces of Laura

Laura? She’s the face in a misty light, footsteps that you hear down the hall, the laugh that floats on a summer night. These words come from Johnny Mercer’s memorable lyrics to “Laura,” a jazz standard that was written by David Raksin to underscore Otto Preminger’s 1944 romantic thriller of that name. It was because of that evocative music that I ended up watching Laura once again.

When the “Laura” theme turned up on my classical music station, I immediately recalled the Preminger film. In my mind’s eye, I could easily picture the cast: Gene Tierney as the beautiful but potentially tragic Laura; Dana Andrew as the clean-cut cop who falls in love with her portrait; Judith Anderson as her cold-blooded aunt; Vincent Price as the parasitic Shelby Carpenter. Most of all, I recollected Clifton Webb’s matchless portrayal of newspaper columnist Waldo Lydecker, whose involvement in Laura’s sad fate is more complex than it first appears. Lydecker, of course, is a smug little man known for his sharp wit and vicious tongue. As he quips, discussing his writing methods, “I don’t use a pen. I write with a goose quill dipped in venom.” He’s the character who has most of the film’s best lines: no wonder Webb was the sole acting nominee from Laura in a year that also featured Gaslight and Double Indemnity, along with unlikely winner Going My Way.

One thing I learned from my local classical music station: Preminger was determined to build his film around a very different musical theme, Duke Ellington’s 1933 “Sophisticated Lady.” It’s a great tune, of course, but one that by 1944 was very well known. When Preminger, a man whose word was law on a movie set, announced to composer David Raksin his plans to use the Ellington piece, Raksin had an immediately objection. The tune, he argued, was just too familiar to evoke the mystery of Laura. Preminger gave Raksin a weekend to come up with something better. Happily for all of us, he did.

The music, though, is not the only thing to admire about Laura . There’s its striking Oscar-winning black & white cinematography, its elegant costumes, its well-matched cast. It’s only in the afterglow of The End that the viewer stops to ponder character motivations that just don’t make much sense. The film was based on a best-selling novel by the once-hugely-popular Vera Caspary. Perhaps in novel form the murky doings of central characters might have seemed more convincing. In any case, Laura was a huge hit for Twentieth Century-Fox. When I wrote about it previously for Beverly in Movieland (March 26, 2013), I had just come from a big-screen showing of the film as part of the L.A. Cinematheque’s annual Noir City series. My friend and film noir expert Alan K. Rode was on hand to explain how Preminger became the director as well as the producer of Laura, despite a serious falling out with Fox head Darryl F. Zanuck over a previous project.

I won’t repeat Alan’s full explanation here, except to say that Zanuck’s first choice for director was the well-established Rouben Mamoulian, who had made cinema history via his experiments with sound in 1929’s Applause, while also directing such landmark Broadway shows as Oklahoma! and Porgy and Bess. But because of questionable casting choices and an insistence that Laura’s essential portrait be painted by his own artist-wife, Mamoulian got the boot. I saw her work hanging on the walls when I interviewed an aged Mamoulian in his home, and I’m convinced that his firing was all to the good.

September 7, 2021

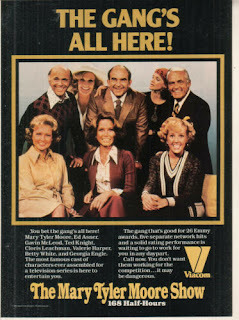

Tears and Chuckles in the Newsroom: Ed Asner Bites the Dust

It’s been a tough year for The Mary Tyler Moore Show. The workplace sitcom, set mostly in the newsroom of a Minneapolis TV station, ran from 1970 to 1977. For me it was essential viewing, as part of a Saturday night CBS comedy line-up. Though not nearly as in-your-face outrageous as 1971’s All in the Family and some of the sitcoms that followed, Mary Tyler Moore contributed to an adult kind of comedy by focusing on a young single woman more focused on her career than on her marital prospects. The show’s most endearing trait, though, was its well-established sense of camaraderie between Mary and her newsroom pals, whose interactions would seem familiar to anyone who’s ever toiled in an office setting. The grumpy boss; the eager assistant; the sardonic sidekick; the social climber; the doofus who somehow succeeds beyond everyone else’s expectations: all of these familiar types make their appearance on the show. But they’re more than simply caricatures: talented writer/creators James L. Brooks and Allan Burns make them real, complex individuals (well, maybe aside from smarmy news anchor Ted Baxter, who gives egotism a bad name). And, from all accounts, the actors playing these roles happily worked together to produce, week after week, can’t-miss TV.

But 2021 has hardly been kind to the Mary Tyler Moore alumni. Over the years, many of the eight regulars passed away, starting with Ted Knight (much acclaimed for playing popinjay Ted Baxter) dying of cancer back in 1986, and the radiant Mary herself succumbing to illness in 2017. Two years later, we lost Valerie Harper, who was unforgettably acerbic as Mary’s lovelorn pal, Rhoda. But 2021 saw the demise of three of the series’ stars. In January it was Cloris Leachman, hilariously neurotic as the narcissistic Phyllis Lindstrom, but also an Oscar-winning dramatic actress (for The Last Picture Show). February brought the death of Gavin MacLeod, who played perennial office wiseacre Murray Slaughter, then went on to other good-guy TV roles. And, of course, last week it was everyone’s favorite newsroom boss, the crusty but fundamentally tender-hearted Lou Grant, played by the invaluable Edward Asner. Asner had a long run as Lou Grant, both on the Mary Tyler Moore Show and later heading up a serious take on newspaper journalism, called simply Lou Grant (1977-1982). So closely was Asner identified with this role that when he appeared in other dramatic contexts, as in the 1977 miniseries Roots, you couldn’t help wondering why in the world Lou Grant was commanding a slave ship.

Like all other fans, I have my favorite episodes. One is the much-acclaimed “Chuckles Bites the Dust,” in which a local TV clown has dressed up as a peanut for a local parade, only to be mauled to death by a confused elephant. The heart of episode takes place at Chuckles’ funeral, where the staff of WJM desperately try to keep from laughing at the whole tragic but absurd situation. But in tribute to Ed Asner, I just watched the series’ last two episodes. In one, Mary and Lou try – at long last – to get romantic, but quickly realize that their work relationship makes courtship impossible. The very last show of all highlights the dispersal of the WJM team after an ownership change and mass firing. The valiantly unsentimental Lou can’t help blurting out, “I treasure you people.” Personally, I feel the same way.

Kudos to sole survivor Betty White. She’s 99 now: may she continue to live long and prosper. Right now I don’t want to lose any more of the show’s alumni.

September 3, 2021

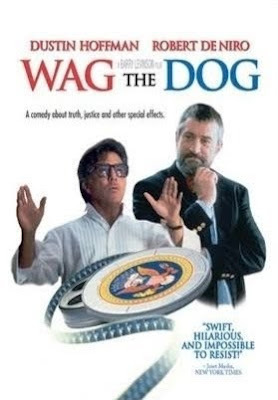

Wagging the (Hot) Dog: Barry Levinson Discovers His Calling

Today—as California moves toward an outrageous recall election and U.S. military spokesmen tapdance around the situation on ground in Afghanistan—it’s not easy to keep politics out of my head. Which is why I returned to one of my favorite Barry Levinson films, Wag the Dog. Partially written by the always razor-sharp David Mamet, and shot in a remarkable (for a star-studded Hollywood flick) 29 days, it is a black-hearted look at how the political process can be manipulated to shape public opinion.

You see, the President of the United States has slipped off to the Oval Office with a young female Firefly Scout. The press has gotten wind of it, and the election is less that two weeks away. POTUS’s loyal staffers, desperate to salvage his re-election campaign, call in top spin doctor Conrad Brean (Robert De Niro), who knows that a big international distraction is what’s needed. Like, maybe, a war with Albania? Such an undertaking needs some Hollywood pizzazz, and Brean knows exactly who to call: producer Stanley Motss (Dustin Hoffman). Motss, still miffed that he’s never won an Oscar, plunges eagerly into this new project, even though he’s been warned he will never publicly be able to claim credit. The heart of the film involves examples of Stanley’s inventive handiwork, like a video clip of a bogus Albanian maiden – with kitten inserted via CGI – telling the camera how badly she needs American intervention to help save her homeland. (She’s played by Kirsten Dunst, looking particularly fetching in her peasant rags.)

When the CIA, in league with the President’s political rival, announces that the non-existent war is over, Brean and his team come up with one final burst of inspiration, in the form of an American soldier supposedly left behind on the field of battle. An Army prison supplies them with the soldier, Sergeant William Schumann, around whom they create an entire heroic mythology involving a nickname, The Old Shoe, and a sentimental ballad theoretically dug out of the archives of the Library of Congress. (Sung by none other than Willie Nelson, it launches a whole campaign of old tennis sneakers being tossed onto telephone wires, in honor of the brave lad.)

I won’t spoil the film’s ending, except to note that Wag the Dog was released in theatres a scant month before a certain U.S. President was making headlines for his Oval Office frolics with a zoftig female intern. And not long thereafter, that administration was bombing Sudan’s Al-Shifa pharmaceutical factory. Life imitating art?

Barry Levinson, who’s still very much an active Hollywood presence, started out as a screenwriter, then made the leap into the director’s chair. His biggest moment as a director probably came in 1989 when he won the Oscar for helming Rain Man. But I’m partial to his 1982 debut film as a writer/director, one that helps capture the Baltimore of his birth. When you’ve been watching classic Hollywood movies, full of snappy dialogue and carefully choreographed movement, Diner seems almost loosey-goosey. This tale of six buddies who hang out afterhours at the local diner is basically a character study, one that conveys a sense of improvisation by its young cast. They’re out of school and restless: even sporting events and marriage pale before the pleasure of being in one another’s company over a plate of fries. Kevin Bacon, Steve Guttenberg, Paul Reiser, Mickey Rourke, Daniel Stern, and Tim Daly have all gone on to major Hollywood careers. But they’ve never been better than in this warm-hearted ode to the American boy-man who hasn’t figured out how to grow up.

August 31, 2021

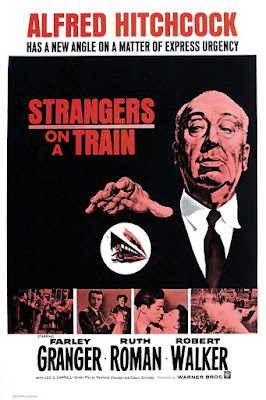

Strangers on a Carousel: Fun and Games with Hitchcock

It’s unlikely that Alfred Hitchcock will be remembered as a comedy writer. His subject matter (which usually focuses on extreme jeopardy) isn’t exactly light-hearted. But as Edward White’s new The Twelve Lives of Alfred Hitchcock makes clear, Hitchcock was deft at using comedy both to make social points and to heighten our sense of impending disaster by forcing us to laugh uneasily at the grotesque within our world. There’s that inevitable banana peel in his best work: the leading character is always about to slip on it, and the results can be hideous or hilarious. Gaiety or gore?: that is the question.

These are the thoughts that run through my mind about one of the master’s best films: 1951’s Strangers on a Train. As usual, Hitchcock based it on the prose work of a talented suspense writer. In this case, the writer was Patricia Highsmith, who 50 years later would be hailed by movie audiences for having created the slippery character of Tom Ripley in The Talented Mr. Ripley and its sequels. (She also wrote the source material for the lesbian drama, Carol. ) Hitchcock and his screenwriters (who included Raymond Chandler) stayed loyal to Highsmith’s basic premise, that—in the course of an accidental meeting—two men discuss a “criss-cross” exchange of murders. Yet the filmmakers gave some significant twists to Highsmith’s original story. Notably, the architect Guy Haines is turned by Hitchcock and company into a noted tennis player, one who tries to laugh off, and then to avoid, the implications of the murderous “bargain” that is insisted upon by the story’s charming psychopath, Bruno Anthony.

None of this may sound funny, but the finished film is laced with Hitchcockian wit. It begins right at the beginning, when the main characters are introduced as two pairs of men’s dress shoes: one sober black and one flashily two-toned, both heading across a train platform. Ultimately, when one pair “accidentally” kicks the other under the table in a dining car, we are introduced to the shoes’ owners, and drama takes over. Much of the film’s macabre comedy involves Bruno (a spectacularly creepy Robert Walker), who has murder on his mind and won’t take no for an answer. (Part of the joke was that Walker was known in his day for playing heroes and good guys.) Bruno, a wealthy idler itching to bump off his own father, lives in a mansion where he sports garish kimonos and enjoys the loyal support of his hilariously dotty mother (a fluttery Marion Lorne). As Bruno skulks through the film, intimidating the weak but well-intentioned Guy (Farley Granger, who helped commit a murder in Rope), fans of the film will remember him particularly as a spectator in a tennis match scene. While all the rest of the tennis fans watch from the bleachers, their heads swiveling as the ball moves back and forth across the net, Bruno sits immobile in their midst, fixedly staring at Guy. Nervous giggles, anyone?

There’s also the fact that the script is full of supporting characters who find the idea of murder amusing. These include a dowager at a party who’s tickled by the whole subject of strangulation and also the filmmaker’s own daughter, the late Patricia Hitchcock, who as the sister of Guy’s beloved enjoys airing her own colorful theories about crime and punishment. Her role is not gratuitous: her thick glasses link her visually to Bruno’s victim, slain amid the fun and games of an amusement park. No surprise that the film ends on a carousel: hilarity and mayhem come together in one jauntily revolving package.

August 27, 2021

The Play’s the Thing: Tom Stoppard Loses It At the Movies

“Inside any stage play there is cinema wildly signalling to be let out.” This Tom Stoppard quote, from the impressive (and weighty) new biography by Hermione Lee, hints at the famous playwright’s complex attitude toward the movies. From his youth onward, Stoppard was a fan of movies, starting with Disney’s Pinocchio, which he saw at the ripe old age of four. As an adult he loved everything. from Marx Brothers laff-fests to European art films to such popular Hollywood fare as The Graduate. (He and its director, Mike Nichols, turned out to have much in common – including early lives disrupted by Nazis – and later became close friends.)

But Lee’s biography makes crystal-clear the gulf between writing for the stage and writing for movies. As the successful playwright of such works as The Real Thing and Arcadia, Stoppard revels in prestige and power. It’s not simply a matter of custom: the legalities of the theatre world stipulate that the text of a play cannot be changed for the purposes of stage production without the author’s consent. Some playwrights are probably shy about exerting their will, but Stoppard is not among them. Although unfailingly polite and collaborative, he insists that any changes to the text of a play be made by him. He also demands consultation on production matters, which means that he’s present not only at rehearsals but also at auditions and meetings of the technical staff. The performance of a Tom Stoppard play is, first and foremost, a Tom Stoppard production.

At the movies, though, it’s the director, not the writer, who is king. (Or, I guess, queen, though female directors continue to be rare indeed.) A major director can hire and fire screenwriters at will, and can even have two writers toiling on the same project without being aware of one another’s existence. Other members of the production team often chime in with their own ideas, and stars have been known to contribute (and sometimes insist on) their own rewrites. This should not be a world in which Stoppard would want to operate, except for the fact that movie gigs are so very lucrative, and Stoppard’s lifestyle is so very lavish.

Stoppard has been credited on several major movies, including the Oscar-winning Shakespeare in Love. He has also directed an ambitious though modestly budgeted 1990 screen version of his own earliest hit, Rosencrantz & Guildenstern are Dead, reasoning that only he would have the audacity to ruthlessly re-focus his own much-admired play. He quickly discovered that he was fundamentally NOT a filmmaker: his instinct was always to focus on dialogue, at the expense of camera movement. Afterwards he acknowledged that a filmmaker, though not a playwright, can change the frame. “In the theatre you’ve got this medium shot, fairly wide angle, for two and a half hours. And that’s it folks.”

Aside from his several screenplay credits, Stoppard has become invaluable to such major directors as Steven Spielberg, because they trust him for smart, honest assessments of their pending projects. For Spielberg, he tried to tamp down the soppy elements that ended the romantic 1989 film, Always, but he also was insistent that Steven Zaillian’s final draft of Schindler’s List not be ”improved” upon. Sometimes Stoppard beefed up dialogue scenes, without screen credit but for serious sums of money. See, for instance, his sparkling work on the key father/son scene between Sean Connery and Harrison Ford in Spielberg’s third Indiana Jones film, which ends with Connery’s Henry Jones telling his long-neglected son that “you left just when you were becoming interesting.”

August 24, 2021

Roping Us In: Alfred Hitchcock’s “Rope”

The grizzly case of Leopold and Loeb has fascinated filmmakers for generations. It was back in 1924 that two wealthy young men from Chicago, convinced of their own intellectual superiority, kidnapped and murdered a 14-year-old boy as an experiment in committing “the perfect crime.” Films inspired by this gruesome episode include 1959’s Compulsion (which focuses on Clarence Darrow’s ringing indictment of the death penalty while defending the two killers), as well as 1992’s Swoon and 2002’s Murder by Numbers. But Alfred Hitchcock—always fascinated by murder and the motives behind it—in 1948 beat everyone else to the screen when he adapted (along with actor/writer Hume Cronyn) a 1929 British play called Rope. This was the period when the always-inventive Hitchcock was trying out new filmmaking techniques. Four years earlier he had challenged his own directorial skills by crafting a survival drama set entirely aboard a small lifeboat in the thick of World War II. (Yes, it was called Lifeboat.) In Rope, he introduced color cinematography, while also shooting and editing in such a way that the film seems to exist in a single long take.

This ambitious attempt to simulate “real time” fascinates film students, though other viewers understandably tend to find it contributes to the movie’s quasi-theatrical stiffness. (The camera occasionally lingers on somebody’s back so that the shooting angle can be changed without our seeming to notice.) From what I’ve read, the actors were not enthralled with all of this experimentation. The set—a posh Manhattan penthouse—was a complicated one, full of walls that could be moved to accommodate lights and camera as well as furniture that had to be hustled out of the way as filming proceeded. I think it was the film’s star, James Stewart, who griped that the only rehearsing that took place involved the constant fully-choreographed rearrangement of chairs, tables, and an essential wooden chest as the drama unfolded.

Aside from its technical challenges, what is Rope actually about? What unfolds is a Leopold and Loeb-like story in which two suave young men strangle a former classmate for kicks, then stuff his body into the chest on which they’ll serve a festive repast while hosting his parents, his sweetheart, and a prep school mentor played by Stewart. We’re asked to believe that Stewart’s character, Rupert Cadell, is the one who first introduced them to the Nietzschean idea that a man of superior intellect can get away with just about anything. To their dismay, though, he refuses to applaud their murderous (not to say sadistic) behavior, and emphatically turns against them.

As in most variants of the Leopold and Loeb story, this one contains hints that the two murderers (well played by John Dall and Farley Granger) are tacitly dealing with their own homosexuality. Playwright Arthur Laurents, who wrote the Rope screenplay when he was barely thirty, was himself a gay man who strongly felt there was a homoerotic element at the center of this story. Talking about Rope decades later, he regretted that Stewart’s character was not also subtly portrayed as gay. (The role had earlier been turned down by both Cary Grant and Montgomery Clift.) Stewart seems uncomfortable as Cadell, and early audiences didn’t respond well to him as a philosophical Nietzsche enthusiast.

One more gripe from Laurents: he had never intended for the murder to be shown in the opening scene. As the film now stands, we know all about the rope, the chest, and the body inside it. Laurens would have preferred for us to wonder—and experience the slowly dawning recognition of the chest’s grim secret.

August 20, 2021

Edith Head Doesn’t Wear Plaid

You’ve got to hand it to Steve Martin. He’s game for anything, from outrageous interracial buffoonery (The Jerk) to an update of Rostand’s 19th century classic, Cyrano de Bergerac (Roxanne). He writes plays too, including a sophisticated meditation on the meaning of genius, as seen in a confab between Pablo Picasso and Albert Einstein (Picasso at the Lapin Agile). In modern art circles, he’s known as a savvy collector and enthusiast. And, of course, he’s been acclaimed for seriously championing the blue-grass banjo.

What works for Martin on-camera (and on-stage) is the clash between his straight-arrow looks and the visual insanity he can deliver. Sporting a well-tailored suit, and with his grey locks neatly coiffed, he looks like a banker. That’s why it’s doubly funny when, as in the priceless All of Me, he goes berserk, galloping madly off in all directions. I love that film, as well as many others in Martin’s canon, but it took COVID (and a recent steady diet of film noir) to induce me to see Dead Men Don’t Wear Plaid. That 1982 film, which also involved the talents of the late, great Carl Reiner, is a spoof of classic detective thrillers from the good old days when men were men, women were dames, and movies were black & white.

Reiner, Martin, and company cleverly built their plot around interpolated footage from old thrillers, finding a way to have Martin’s character converse (in tough-guy detective-eze) with everyone from Bette Davis to Jimmy Cagney, from a panicky Barbara Stanwyck (in a clip from Sorry, Wrong Number) to a woozy Ray Milland (The Lost Weekend) to a stoic Burt Lancaster (The Killers). Walter Neff, the leading character played by Fred MacMurray in Double Indemnity, turns out to play a key role in Martin’s case, which involves the murder of a prominent scientist and cheese-maker. And when Martin’s detective character needs extra hands on the job, he calls in Philip Marlowe (Humphrey Bogart), who provides him with tips over the telephone.

It’s a triumph of film editing, as well as a project that calls on the talents of art directors and others who can bring off the look of 1940s noir. In the case of costume design, the artistic team hit the jackpot by hiring Edith Head, in what was to be her very last film. The eight-time Oscar winner, who had become famous in 1937 for designing Dorothy Lamour’s sarong, knew just how to outfit Martin and his femme-fatale client (Rachel Ward) in clothes of the era, including a snappy fedora for him and a wow of a picture-hat for her. After all, the 433 films on which Head is credited include such Forties classics as The Lost Weekend, Sorry, Wrong Number, and Double Indemnity.

I remember once, as a UCLA grad student in the Young Library stacks, putting aside my research to speed-read Head’s fascinating 1959 memoir, The Dress Doctor. It describes her life in Hollywood, designing costumes for glamorous stars with shaky egos. To make clear she was NOT competing with her famous clients, Head smartly decided to play down her own appearance. That’s why she settled on a distinctive but drab look: huge owlish glasses, prim suits, heavy bangs. Her schoolmarmish choices for herself instantly made it clear: this lady meant business. (I also learned from the book something it’s nice to keep in mind: no celebrity, however gorgeous, is without figure flaws that must be camouflaged by clever design.)

Today Edith Head is gone but not forgotten. See Pixar’s The Incredibles, where pint-sized designer Edna Mode is made in her image.

August 17, 2021

When Mob Rule Prevails: The Ox-Bow Incident

My parents, who had no love for westerns, made an exception for The Ox-Bow Incident. And no wonder! This 1943 drama, directed by William Wellman from a novel by Walter Van Tilburg Clark, is hardly a glorification of machismo on the range. Instead, it’s a sobering study of mob mentality, graphically revealing what happens when a community is overcome by bloodlust.

Anyone watching The Ox-Bow Incident today will be struck by the fact that its settings (supposedly high in the mountains of Nevada) don’t seem entirely convincing. Much of the action looks like it was filmed on a studio lot, and indeed it was. Because Ox-Bow was made in wartime, location shooting was an expensive luxury that mostly couldn’t be justified. But I’m struck now by how this film, by implication, has something to say about why men go to war in the first place. The movie begins as news arrives in a small western town that a well-respected rancher has been shot in the head and his cattle stolen. Immediately a mob forms in front of the local saloon, and there are loud cries for vengeance. Among those clamoring to form a posse to catch and lynch the culprits are many with their own agendas. One dour man in black is convinced that the arm of the law moves too slowly for true justice to be done. Another, the town drunk, is excited by all the talk of bloody vengeance. In the absence of the local sheriff, his newly-appointed deputy is determined to show off his own authority. A Civil War veteran who has a fancy uniform but a questionable war record takes on a leadership role, partly as a way of trying to force his gentle son to man up. Among all these blood-thirsty men is one woman (Jane Darwell), who enjoys being even more tough-minded that her male counterparts.

It’s a surprise to see Darwell talk tough here, when we remember her so vividly as the gentle, noble Ma Joad in 1940’s The Grapes of Wrath. In that great film, Henry Fonda played her loyal son. Here, by contrast, he’s dead-set against her as she clamors for vengeance against three men who are fast asleep when found by the mob. Circumstantial evidence makes them seem guilty of the crimes, though the well-spoken Donald Martin (a fine performance by Dana Andrews) tries hard to explain why he and the other two (including a shady Mexican played by the young Anthony Quinn) are by no means culpable. There’s a haunting scene in which, facing death at sunrise, Martin pens a farewell letter to his wife back home while the posse celebrates with liquor and raucous song.

Andrews’ performance is powerful, but the focal point of the picture remains Fonda, as a drifter with local ties. He may have a chip on his shoulder (for one thing, he’s just been dumped by the woman he loves), but he’s still got that fundamentally noble streak that’s embedded in so many Fonda characters: he rides out with the posse partly in the name of self-preservation, but he can’t bring himself to accept mob rule as a form of justice. By the time he made this film, Fonda was a Hollywood star, one whose best roles were low-key but fundamentally heroic. His personal politics—involving respect for the common man—always shone through on the screen. When he was a boy in Omaha, his father took him to the site of the lynching of a Black man. The object lesson was clear: this was what happened when people forgot about their essential humanity.

August 13, 2021

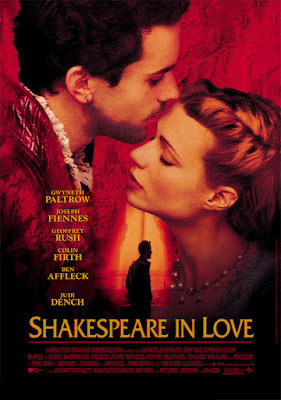

"Shakespeare in Love": A Viola by Any Other Name

You may think it’s a travesty that I’m dodging away from my passion for movies in order to dip into Hermione Lee’s new biography of the Czech-born British playwright, Tom Stoppard. Stoppard, though lacking any fancy university degrees, is known for his erudition and wit. These hallmarks are revealed in his many plays, including the award-winning Arcadia and The Real Thing. But what struck me about the early pages of this biography is that as a young man coming of age circa 1960 Stoppard had many of the same cultural passions that my classmates and I did, though we were slightly younger. He admired the works of Samuel Beckett and Britain’s “Angry Young Men” like John Osbourne (Look Back in Anger). But a lot of his enthusiasms were for American cultural figures: Hemingway, Arthur Miller, T.S. Eliot. He also adored the films of Buster Keaton and the Brothers Marx. As a struggling journalist on his first trip to America, he somehow managed to meet and chat with funnyman Mel Brooks, and considered this one of the highlights of his young life.

As a pater familias trying to support a growing household, he was of course eager to put his talents to work on Hollywood properties, in exchange for Hollywood-sized paychecks. A commission to adapt Bertolt Brecht’s Galileo for the screen came to nothing. But once his fame as a playwright was secure, he had a hand in some oddly assorted projects. In 1985, he contributed to the hilarious and disturbing dystopian fantasy, Brazil, along with Charles McKeown and Terry Gilliam of Monty Python fame. (The screenplay was nominated for an Oscar.) In 1987 he worked on the first draft of Empire of the Sun, This film, directed by Steven Spielberg and with a young Christian Bale in the central role, was an adaptation of J.G. Ballard’s semi-autobiographical account of being a British boy stuck in a Japanese-run POW camp in China during World War II. (The experience led Stoppard to relieve his own family history of seeking refuge from the Nazis in first Singapore and then India.) He also wrote the 1990 screen adaptation of John Le [image error]’s The Russia House.

But none of his other screen projects has been as peculiarly Stoppardian as his screenplay for 1998’s Best Picture, Shakespeare in Love. The combination of Shakespeare and Stoppard is a potent one: he had burst onto the theatre scene with his own sideways take on Hamlet, 1966’s Rosencrantz &Guildenstern are Dead. It was not Stoppard’s idea to show a young Will Shakespeare, paralyzed by writer’s block, finding new inspiration when a lovely woman disguises herself as a man to audition for his upcoming comedy, tentatively titled Romeo and Ethel the Pirate’s Daughter. The concept, and the title of the film, came from an American TV writer, Marc Norman, who ultimately shared the screenplay Oscar with Stoppard. But clearly it was Stoppard who made the screenplay bubble over with high spirits and deep emotions. His interweaving of Shakespeare’s tragic Romeo and Juliet with the doomed romance of Will Shakespeare and Viola de Lesseps is funny, sexy, and ultimately poignant. It also provides meaty roles for some of England’s finest players, including Judi Dench as a knowing Queen Elizabeth, Colin Firth as a crass Lord Wessex, and Geoffrey Rush as the owner of the Rose Theatre, always desperate for a lucrative comedy containing hijinks and a dog. As a satire of show biz today, as well as a romance for the ages, Shakespeare in Love is priceless. The rivalries, the neuroses, the vanity the stage engenders—it’s all here. Bravissimo!

August 10, 2021

Seeing Double (Indemnity)

The Best Picture Oscar for 1945 went to a sentimental 1944 confection called Going My Way, full of lovable priests, scrappy orphan kids, and Bing Crosby crooning “Swinging on a Star.” (I just learned Going My Way was largely filmed not far from me, in Santa Monica’s own venerable St. Monica’s Catholic Church.) The film won eight Oscars, including a Best Actor statuette for Crosby at his laid-back best. Ireland’s Barry Fitzgerald copped an Oscar too: remarkably he was nominated both in the Best Actor and Best Supporting Actor categories, prompting a key rule change.

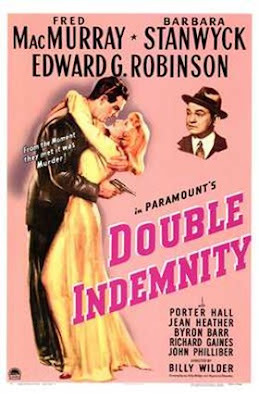

I suspect that in early 1945, with World War II finally drawing to a close, both critics and audiences (not to mention Academy voters) were eager to reward movies that always looked on the bright side. In competition with Going My Way for its various Oscar honors were soppy tearjerkers (Since You Went Away) and some of Hollywood’s grandest, darkest takes on crime and punishment. This was the year of Gaslight, Laura, and a noirclassic, Double Indemnity. None of these, surely, was designed to cheer the war-weary, but they still appeal to all of us who like our entertainment with a frisson of danger.

Double Indemnity was nominated for seven Oscars, but nabbed nary a one. It essentially launched Billy Wilder’s brilliant directing career: he was nominated for his direction of the film, and also for the screenplay on which he collaborated with none other than Raymond Chandler, adapting a novel by James M. Cain. His leading lady, the dangerously sultry Barbara Stanwyck, was a Best Actress nominee for Double Indemnity, but lost as she had before and would again. The film’s two key males, Fred MacMurray and Edward G. Robinson, gave brilliant performances but were entirely overlooked by members of the Academy. In later years, MacMurray would find his greatest success in Disney comedies and as a fumbling father in My Three Sons. I would never have guessed, when watching him be avuncular in Son of Flubber, that he’d make such a memorable heel.

Filmmakers used to love casting Stanwyck as a smart, conniving dame falling for an innocent, good-hearted guy. (See, for instance, her pairing with Gary Cooper in Wilder’s Ball of Fire.) In Double Indemnity she’s still smart and conniving, but her leading man, MacMurray, is no innocent. As insurance salesman Walter Neff, he’s clearly proud of his conquests, actuarial and otherwise. He’s making time with Stanwyck’s unhappy housewife from the get-go, and he’s quick to come up with a “double indemnity” scheme that will help all of her marital problems go away, while leaving the two of them rolling in dough. The trouble with Walter: he’s not as smart as he thinks he is. The plot goes off without a hitch . . . until it doesn’t. And I don’t feel required to add a spoiler alert, because – through the film’s classic use of voiceover narration -- we know from the start who did what to whom. There is, of course, a sly final wrinkle we probably didn’t see coming.

Wilder’s touch can be found in the film’s crackling dialogue, and also in some effective directorial flourishes. My favorite involves the connection between MacMurray and Robinson as his crusty but tender-hearted boss. Throughout the film, MacMurray has been quick to strike a match, lighting Robinson’s ever-present stogie. Then, as all hope fades for our hero, it’s Robinson’s Barton Keyes who supplies the flame for the cigarette of his failed protégée. If only Neff had had his mentor’s clear-eyed vision . . . but then we’d be without this great film.

Beverly in Movieland

- Beverly Gray's profile

- 10 followers