Beverly Gray's Blog: Beverly in Movieland, page 44

August 6, 2021

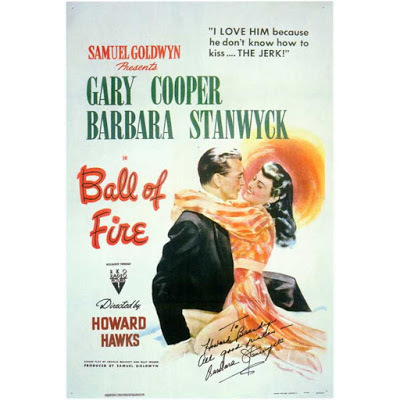

Happythankyoumoreplease: Lower Manhattan is for Lovers

Do you like New York in June? Do you ponder what street compares with Mott Street in July, with its pushcarts gently gliding by? If these lyrics by Burton Lane and Lorenz Hart (from, respectively, “How About You?” and “I’ll Take Manhattan”) strike a chord, it’s because they conjure up the romance of New York City, as described by some of our greatest American lyricists. They’re not talking about the New York of glitzy skyscrapers and the big-bucks wheeler-dealers of the Stock Exchange, but rather about a place that, despite its crowds and its sometimes seedy surroundings, is an island of low-key romance.

The movies too have often used Manhattan as a backdrop for romantic escapades. It’s not just Woody Allen: since the very beginning filmmakers have focused on love (not just sex) in the city. Examples are almost too numerous to name, but think of everything from Breakfast at Tiffany’s to Crossing Delancey to Green Card to 2019’s Rebel Wilson romp, Isn’t it Romantic. In search of lighthearted entertainment, I happened upon a 2010 Sundance award-winner that’s easy to like, even though it falls back on the clichés of falling in love, New York-style.

Happythankyoumoreplease is a deceptively ambitious undertaking of Josh Radnor (of TV’s How I Met Your Mother), who wrote, directed, and starred in this frothy romance in which six (mostly) 20-somethings, all of them residents of Lower Manhattan, seek and find love, sometimes in unexpected places. True to the genre, there’s even some requisite L.A. bashing (see Annie Hall), with one character on the brink of making a major career move to the land of the smoggy palm. To be fair, the character who most resists the possibility of life in L.A. is perhaps its most neurotic. As Zoe Kazan’s on-screen boyfriend points out, the New York cultural monuments she can’t bear to leave behind are places she never visits.

Along with Kazan, the screen is filled with rising young performers, some of whom have gone on to do much bigger things. Malin Akerman plays a young woman suffering from alopecia who parlays a unique sense of style into a surprising but sweet romance with Tony Hale. (The sheer unexpectedness of this odd-couple relationship, which slowly unfolds throughout the film, makes it my favorite.). Meanwhile Radnor’s struggling novelist (is there any other kind?) character is head-over-heels for would-be chanteuse Kate Mara, who’s full of regrets that she tends to give her heart (and her body) too easily. And Kazan can’t quite commit to adult-style life with budding screenwriter Pablo Schreiber.

All these characters are talented and arty, but most seem to live alone in cramped but cozy New York apartments without the encumbrance of an actual job. That’s one of the ways this film is something of a fairytale. Also exceedingly upbeat is the relationship between Radnor’s Sam and a small Black kid he accidentally meets on the subway. It’s meant as just a soupçon of reality: Rasheen is a victim of foster care, one who’s happy to opt out of the system and just hang with the good-hearted Sam instead of being returned to the woman who’s supposed to be caring for him. Rasheen’s a likable presence, but it ultimately seems clear that reality needs to intrude on his new living situation. And so it does, for a few seconds, when Sam gets picked up by the police. But this being the kind of movie it is, the problem is quickly solved and all’s well that ends well. Which is what you expect—and maybe deserve—in a summer New York romance.

August 3, 2021

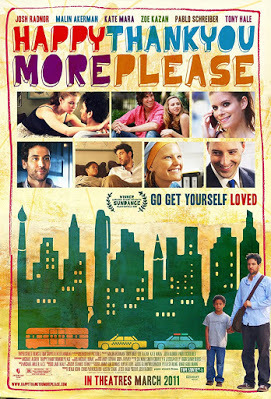

Dial H for Hitchcock

Summer is supposed to be the time for light-hearted amusements, but I suspect the book I’ve just finished doesn’t exactly count as an appropriate beach read. It’s Edward White’s brand-new The Twelve Lives of Alfred Hitchcock: An Anatomy of the Master of Suspense. Maybe it’s the resurgence of COVID-19 that has prompted me to choose a book in a minor key. But it’s also true that this unorthodox biography is smart and original, as well as sometimes quite amusing, much like the man himself.

Why not write a cradle-to-grave biography of Hitchcock? As White points out, such books already exist. Instead, he divides his study of Hitchcock into twelve sections, each exploring a different aspect of the master’s life and work. The tantalizing list of chapter titles immediately provoked my curiosity. White starts out with “The Boy Who Couldn’t Grow Up,” discussing young Alfred’s childhood fears and revealing how these perhaps show up in his handling of innocent children in films like The Birds. Next comes “The Murderer,” regarding a shy man’s fascination with murder as a perverse sort of art form. This leads to a fascinating suggestion that Psycho was, among other things, Hitchcock’s response to the rise of the television generation, as well as a precursor of the various real-life horrors of the Sixties, including the Zapruder tapes, the Vietnam War, and the bloody doings of the Manson family. (I learned for the first time that just after World War II Hitchcock was hired by the British Ministry of Information to edit found footage of the Nazi death camps.)

There’s a chapter, of course, on Hitchcock’s complex dealing with women, whom he took a delight in degrading on screen, while also relying heavily on his sensible wife. And there’s a chapter on his gourmand-ish relationship to food, as well as his ambiguous view of his own weight issues. (He was hugely self-conscious of his looks, but also knew how to poke public fun at his own stabs at dieting: see how the clever Hitchcock cameo in Lifeboat is tucked into a newspaper ad for a diet plan, complete with before-and-after photos.) Chapter 6, “The Dandy,” explores Hitchcock’s rigid personal sartorial code, and then dips into his subtle use of actual gay actors to hint at the homosexual aspects of a senseless crime in Rope. No surprise that the chapter on “The Voyeur” features Rear Window, comparing its housebound protagonist (played by James Stewart) to Hitchcock himself, as a man who gets his jollies by peering from afar at the perversities of others.

Chapter 9, “The Entertainer,” zeroes in on how and why Hitchcock uses humor to leaven the horror of many of his films. “The Pioneer” pays tribute to the myriad ways in which his filmmaking can be considered artistically revolutionary. I was intrigued by how White, an Englishman, sees in Hitchcock a peculiarly British perspective, especially when it comes to the English delight in watching the once-mighty get their comeuppance. (Much attention is paid in this chapter to Hitchcock’s early, London-based, film work.) And the unexpected final chapter, “The Man of God,” weighs the impact on Hitchcock – both the young boy and the old man nearing death –of his family’s deep-seated Roman Catholic faith.

Along the way, I discovered that it was Hitchcock films like Vertigo and Marnie that cinema scholar Laura Mulvey was remembering when she formulated her influential theory of the “male gaze.” And among the important Hollywood auteurs who took lessons from Hitchcock was Martin Scorsese, who reworked aspects of Hitchcock’s The Wrong Man into Taxi Driver. Who knew?

July 30, 2021

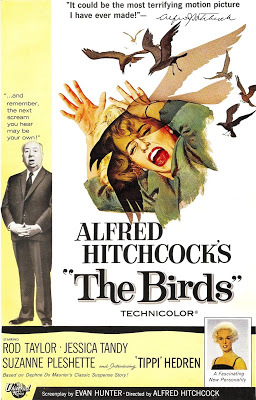

Walking, Not Running, to Cinematic Gold: The Olympics at the Movies

I’m a great armchair Olympics fan. Much as I love movies, I’m mesmerized by spectacles, like sporting events, in which the outcome is entirely uncertain. In which the better competitor – at least on paper -- doesn’t always win. But watching the 2020/2021 Olympiad is not always pleasant. There’s been joy, certainly, but often the mood has been sober, even somber. It’s daunting to learn that Simon Biles is human after all, and even more daunting to discover that the boo-birds are now calling her names because, at a time of personal crisis, she’s not willing to put her body at risk for the sake of a medallion on a ribbon.

Of course there’ve been movies about the Olympics, largely more focused on the joy of victory than the agony of defeat. After all, we expect our Olympics movies to be uplifting. One that certainly filled the bill was the 1982 top Oscar winner, Chariots of Fire. Some consider it soppy now, but I look back on this film with great pleasure. It’s a canny mix of history lesson and heart-tugging emotion, highlighting the fate of two very different runners on the British team that traveled to Paris in 1924 to compete in Olympic track and field. Ian Charleson plays Eric Liddell, a Scottish missionary to China who runs for the glory of God. Ben Cross portrays Harold Abrahams, a Jewish student at Cambridge who fights class snobbery and polite anti-Semitism as he exercises his passion for running. Each of the men succeeds, in his own way, with Abrahams, despite his less-than-lofty pedigree, going on to become the grand old man of British athletics. Hokey? Maybe, but it really happened, and it’s fascinating to see the early days of a famous sports competition. And that much-parodied opening, with the runners – in training – striding down a Scottish beach to the majestic Vangelis score never fails to inspire me.

The Tokyo Olympics of 1964 itself led to several films. One was a masterful documentary, Tokyo Olympiad, by Kon Ichikawa. Far more than a record of what happened at the Olympics that marked Japan’s post-war rise, it is a celebration of athletes and athletics, as well as a joyous view of the people of Tokyo interacting with a world event. The other film that captures (sort of) the Tokyo I remember from my college days is a breezy 1966 romantic comedy that updates a 1943 feature called The More the Merrier. The original had lampooned the post-World War II housing shortage in Washington DC. Walk, Don’t Run takes that plot thread and applies it to Tokyo, just prior to the Olympics: pretty Samantha Eggar announces she’ll be willing to share her apartment during the games, but she’s shocked when her applicant turns out to be Cary Grant, in his last film role, as a suave British tycoon who’s arrived too early for his luxurious hotel suite. And she’s even more flummoxed when Grant invites in a needy young American architect (Jim Hutton) who also happens to be a U.S. team member. Naturally, sparks fly, though Grant (who at sixty-plus had decided he was too old for romantic roles) plays Cupid, not Romeo.

The film makes much (rather dated) comedy out of national stereotypes: obsequious Japanese, stuffy British, brash Americans, Russians bent on either drinking or spying. And despite the glimpses we catch of authentic Olympic venues, the film’s handling of the actual games is not exactly convincing. But the scene of Grant, in his skivvies, race-walking through crowded Tokyo streets to stave off a romantic kerfuffle is one worth savoring.

July 27, 2021

“El Camino”: Too Much of a (Breaking) Bad Thing?

I recently spent months on my couch, catching up with Breaking Bad. This series (2008-2013) certainly deserves its accolades. Its characters are convincingly complicated; its storyline is riveting; its cinematography is endlessly inventive (the high desert of New Mexico has never looked so ominous, nor so beautiful). I’m a particular fan of those opening sequences that drop you into each week’s story from a skewed perspective (maybe a baffling flash-forward, possibly a wacky Spanish-language narco corrido in praise of that elusive drug lord, Señor Heisenberg).

Perhaps the theme running through the entire series is how people react to change. When a mild-mannered chemistry teacher named Walter White is diagnosed with late-stage lung cancer, his life slips into a different gear. Desperate for money to support his growing family, he discovers a lucrative new career as a maker of primo methamphetamine. His crossover onto the shady side of the law brings out personality traits that have previously remained hidden: like a lust for ever-increasing power. And his evolution soon transforms his family: his very pregnant wife, his straight-arrow brother-in-law, his loyal son who won’t let cerebral palsy get him down. Before long, a good swath of Albuquerque is somehow caught up in his rise and eventual fall.

One character, a reckless young drug dealer who shows “Mr. White” the ropes of meth-peddling in season one, was supposed to be snuffed out early on. But Jesse Pinkman’s working relationship with his former high school teacher proved so potent that Jesse was turned into a series star. Impetuous and self-destructive, but also tender-hearted and smart, Jesse was shaped by the writers into the able-bodied son Walter never had. As Walt becomes more and more of a monster, Jesse haltingly moves in the other direction, trying to make up for the harm he’s caused. That’s why, in the series’ final moments, he’s the one character who (with a little help from his friend) escapes from a bloodbath, lighting out for the Territory with tears in his eyes.

For all the havoc he causes, Jesse (played with deep conviction by Aaron Paul) is a character who’s easy to love., because he’s so quick to acknowledge his failings. That’s why I was eager to follow up on Jesse’s post-Walt story by way of 2019’s feature film, El Camino, produced by the Breaking Bad team as a sort of a sequel to the series.

El Camino, named for the automotive classic in which Jesse makes his escape from the house of death, starts with its protagonist in flight. But, perhaps to capitalize on viewers’ fond recollections of the series, it also flashes back to happier days of Jesse absorbing life-lessons from Walt, from fixer Mike Ehrmantraut, and even from the drug-addled Jane, his one-time girlfriend before her fatal overdose. What’s more, it wallows in Jesse’s suffering before that final shootout, giving us plenty of footage of Todd, a young, red-headed meth gangster who could alternately be called Jesse’s evil twin and Opie gone to seed. (He has just bumped off his cleaning woman, whom he repeatedly describes as “a very nice lady.”) This is all in the past, but the present-day story piles on the complications involved in Jesse drumming up the cash he needs to blow this popsicle stand and start a new life somewhere else. His goal is to find and reclaim the bad guys’ ill-gotten gains, which involves much deceit, many close calls, and (of course) loads of blood. Whereas the TV episodes all seemed cannily plotted, this full-length movie is both confusing and, ultimately, dull. Poor Jesse! Poor me!

July 23, 2021

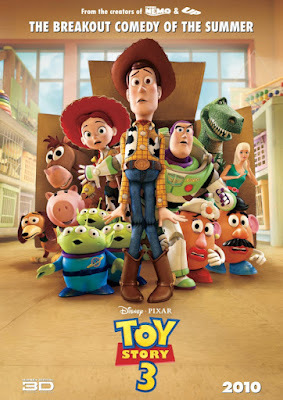

The Never-Ending (Toy) Story

I generally avoid movies whose titles end with a number, like Jaws 2 or The Fast and the Furious 5. As I have good reason to know (having worked on Corman franchises like Bloodfist and Slumber Party Massacre), each movie that follows the original is a bit less clever, a bit more predictable. But the good folks at Pixar were not about to let their Toy Story sequels disappoint their loyal fan base. Remarkably, 2010’s Toy Story 3, which I just rewatched, may be the best of the lot. Sure, it still contains familiar characters like valiant Sheriff Woody, spacey Buzz Lightyear, the Potato Head pair, and a fearful Tyrannosaurus Rex, all of them loyal to “their” kid, Andy. But the thing is—Andy is now almost eighteen, and on his way to college. The toys haven’t changed over time, but Andy has. And time becomes film’s big (if hidden) subject.

This makes it quite a different story from the previous two Toy Story films. The original dealt with such child-appropriate topics as jealousy and friendship. In that 1995 film, the arrival of Buzz—who becomes Andy’s new favorite—rocks Woody to the core. But when the chips are down, Woody and Buzz learn to work together and forge a solid friendship, as underscored by Randy Newman’s Oscar-nominated song, “You’ve Got a Friend in Me.” Their relationship continues in Toy Story 2 (1999), in which Buzz needs to come to the rescue of Woody, who’s been kidnapped (toynapped?) by a dastardly collector with plans to send him to Japan.

But by 2010, the original film’s target audience was on the brink of adulthood, and largely leaving all things Disney behind. In a way, Toy Story 3 is directed at their parents, who have deeply mixed emotions about seeing their offspring fly away from the nest. Yes, Andy’s mom is eager to see him clear out his childhood toys before he goes off to college, but she is still feeling the loss of the little boy she once knew and loved. What happens to the toys that may be headed for the attic—or scrapped—is what this story is about.

Since the Pixar team understands that young viewers prefer excitement to philosophy, there’s plenty of derring-do here, like some heroic flights from a garbage truck and from a childcare center that seems a paradise but is ruled over by a menacing pink stuffed bear who smells like strawberries (the late Ned Beatty, full of Southern charm and menace). A sequence at the city dump has an Inferno quality, but – of course – ends in a breathless escape. And I defy parents not to be moved when Andy decides what best to do with well-loved toys he’s outgrown.

Pixar is good, too, at finding ways to tickle adult funny-bones. At the childcare center where the discarded toys briefly find a home, a vapid Barbie (in Jane Fonda-style leotard and leggings) finds the Ken of her dreams, then later tricks him into modeling his elaborate Sixties wardrobe (tie-dye! an astronaut suit!) when he needs to be distracted from the big escape attempt. And I suspect we Boomers remember many of the vintage toys in the film, like the Slinky-dog, the GI Joe action figures, and that talking telephone. The film has more serious matters on its mind, too, like our throwaway culture that decrees that anything out of date should simply be tossed, and that most of our once-cherished possessions ultimately belong in a landfill.

All in all, it’s a beautiful film with a perfect ending. But then they made Toy Story 4.

July 20, 2021

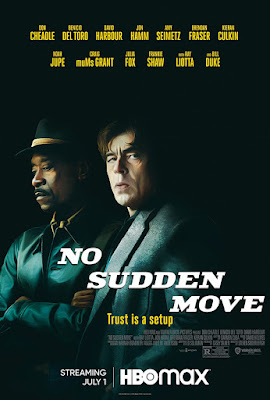

Hold Still for “No Sudden Move”

When I was growing up, my family’s most spectacular automobile was a 1959 Buick, a sleek highway beast with tail fins and a metallic paintjob in a shade called “Lido Lavender.” Traveling ‘cross-country in that remarkable car, each of us could feel like a king (or queen) of the road. I mention this now because Steven Soderbergh’s new crime drama, No Sudden Move, is similarly in love with cars, though from a slightly earlier vintage. His film is set in 1954 Detroit, which was then the auto capital of the world. But the vehicles featured in his convoluted story are not yet low and sleek. Instead they’re massive, bulbous muscle-cars, even when painted in fetching, feminine shades of aqua. It’s all fitting, because this tale of life in the Motor City hinges on cars—and muscle.

Soderbergh started his rise in the film industry with a low-budget Sundance hit, Sex, Lies, and Videotape. I think of this as a chamber-piece, focusing tightly on four intertwined characters: a young wife (Andie MacDowell), her faithless husband (Peter Gallagher), her good-time sister (Laura San Giacomo), and the mysterious stranger (James Spader) who breezes into town with strange quirks of his own. It’s a beautifully crafted little drama, both written and directed by Soderbergh, who used this as his ticket to much bigger, gaudier efforts. From the looks of his filmography, it seems Soderbergh likes Wagnerian symphonies better than chamber music. His hits have included epic fare like Traffic and Ocean’s Eleven as well as the recent The Laundromat: he seems to like nothing better than plunging into a hot-bed of criminal behavior and following wherever it leads.

In the case of No Sudden Move, we’re first introduced to grifters who represent two different crime communities. Don Cheadle is an African-American with a checkered past; Benicio del Toro has Italian mob connections. Both are so desperate for work that they take on a strange job keeping a suburban family at gunpoint while the husband is carted off to open a safe belonging to his boss. Why’s the safe empty, and what do the missing documents represent? By the time this is sorted out, a lot of people are dead, others are badly bruised, and the auto industry continues to reign supreme. Yes, the auto industry—this is not merely a crime film but also an indictment of industrial collusion, loosely based on a genuine incident from America’s past. It all comes home to us in a key speech by a surprise (and unbilled) character, who —late in the film—looms somewhat in the way that Ned Beatty did in Network, delivering a monologue that brings Soderbergh’s bigger political and social point into focus.

If the action in the film seems all about guys and guns, think again. The women in No Sudden Move may be housewives and secretaries, not gangsters and crooked gumshoes, but in the grand scheme of things most of them are equally culpable. They too know what they want (perhaps more clearly than most of the men do), and they’ll stop at nothing to make their dreams come true. Don’t let their aprons and bouncy curls fool you: these femmes are quite capable of being fatale.

There’s hardboiled humor in the film, and almost no one you could call particularly nice. Heroes, let us say, are in short supply, though one teenage boy is sure trying hard to save his family. But maybe, after a year of quarantine (not to mention a political insurrection), we’ve become cynical enough to appreciate a story in which no one is much good at all.

July 16, 2021

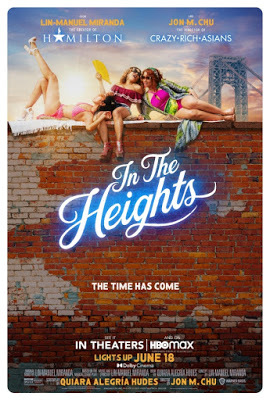

Going Wide-Screen with “In the Heights”

Lin-Manuel Miranda seems one of those rare Americans who can do no wrong. He’s charming! He’s funny! He’s personally gracious and politically “woke”! Miranda took a serious political biography about one of our country’s founding fathers and turned it into a megahit Broadway musical, with himself in the leading role. (Now the video version of Hamilton – basically a well-crafted filmed play – is up for a remarkable 12 Emmy awards.) Naturally, Hollywood has taken an interest. Miranda has played a variety of roles and raked in an Oscar nomination for his anthem, “How Far I’ll Go,” which plays a key role in Disney’s Moana. And he’s turned to film directing as well, with the upcoming tick, tick . . . Boom! It’s a tribute of sorts to Broadway’s Jonathan Larson, who wrote an autographical play about a struggling young musical-theatre composer, then died on the eve of the triumphant debut of his 1996 play, Rent. So one apparent genius (yes, Miranda owns one of those MacArthur “genius” grants) pays homage to another.

In 2008. seven years before Hamilton, Broadway playgoers saw another Miranda opus, In the Heights, one that reflected his own upbringing in Manhattan’s heavily Latino Washington Heights. The show, again with Miranda in a key role, won the Tony Award for Best Musical, in what admittedly was a sparse year for musical hits. (Ever hear of Passing Strange? Cry Baby? Xanadu?) I happened to see the original cast in action. While I loved the show’s Latin rhythms and couldn’t fault the performers, I found the story lackluster at best. Yes, it was interesting to see ethnic Dominican and Puerto Rican immigrants to New York City reveal their challenges and their longings, but the specific characters on whom the plot focused seemed thinly drawn. In the stage version, In the Heights concentrates mostly on a Romeo and Juliet romance between the academically successful Nina and a young African-American named Benny, who works for Nina’s father’s car-service company. This schmaltzy clash of cultures as well as education-levels is complicated by Nina’s struggles as a homesick freshman at faraway dream-school Stanford.

When it came time to make the movie, Miranda and company smartly shifted the story’s chief focus from Nina and Benny’s forbidden (and not all that convincing) love to another of the play’s couples. On stage, Usnavi— the owner of a local bodega but one who longs to return to his native land -- was played by Miranda himself, mostly as a rap-happy narrator for the proceedings. Now, in his forties, he’s given himself a much smaller but still colorful role as a seller of piragua (shaved ice) who’s caught in a quiet battle with the local Mr. Softee vendor. (Don’t miss the Easter Egg at the very end of the credits, showing who is the victor in their long-term rivalry.) Meanwhile Usnavi, now played by the fresh-faced Anthony Ramos, becomes one of the film’s romantic leads, as he yearns for the affection of the ambitious, artistic Vanessa.

It’s a smart re-think of the story, though the still-present Stanford subplot strikes me as sloppy and bogus once more. (Here’s a great take-down by an actual Stanford graduate from a background similar to Nina’s.) But I chose this film for my return to the cineplex because I wanted to see its musical numbers in all their glory. They are indeed glorious, if perhaps overwhelming after a while. Everyonesings and dances – young kids, abuelas – on the streets, in the public swimming pool, up and down the sides of tenement buildings. Perhaps this feel-good film is just what we need right now.

July 13, 2021

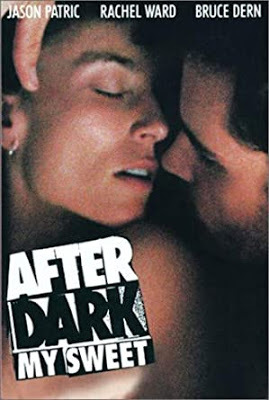

A Palm Springs Noir, My Sweet

Palm Springs Noir? The words suggest steamy doings in bone-dry terrain: crimes amid the cactus, double-crossing and doubling down in the precious palm-lined oases that secure a lush life for some but hardly for all. Palm Springs Noiris a terrific new anthology from Akashic, which has made a point of publishing geographically-inspired noir story collections for decades. (Copenhagen Noir, anyone?) The editor of this latest volume in the series is Barbara DeMarco-Barrett—writer, editor, and desert-lover—who happens to be my longtime friend and colleague.

The writers in Barbara’s collection (including big names like Janet Fitch and T. Jefferson Parker) were carefully chosen both for their talent and their familiarity with Palm Springs and surrounding towns. Each casts a jaundiced eye on the staples of this landscape: swimming pools, mid-century-modern décor, trailer parks, Airbnb rentals, gardeners spritzing the luxuriant foliage despite a dwindling water supply.

Film Noir of course is the term that French cinéastes have applied to the tough-minded black-&-white thrillers that Hollywood churned out in great numbers circa 1940. Think Double Indemnity and other flicks in which dames like Barbara Stanwyck were up to no good. So it occurred to me to wonder, given how much Hollywood types in the Forties loved to frolic in Palm Springs, whether any films of the noir era depicted that locale. Eric Beetner, whose “The Guest” is one of the gems of the new collection, admitted to me that surprisingly few films were set in the Palm Springs environs during the noir era. While the ending of High Sierra was indeed shot near Palm Springs’ high-desert region, he mostly cited obscure entries like The Threat, “a good and underseen movie with the amazing Charles McGraw.” But Beetner also came up with a 1990 neo-noir that seemed worth checking out. Which is how I came to watch 1990’s After Dark, My Sweet, shot entirely in the Palm Springs-adjacent city of Indio. (Indio, a blue-collar town once best known for date-growing but now the site of the Coachella Music and Arts Festival, is the setting for a creepy Tod Goldberg story, “A Career Spent Disappointing People,” that continues to haunt me.)

After Dark, My Sweet, based on a Jim Thompson novel, involves such noir staples aa a down-at-the-heels ex-boxer, a beautiful widow, and a shifty guy out to make a buck. There’s cool voiceover narration and a twisty plot about a kidnapping gone awry. Director James Foley, who got his start directing Madonna’s music videos, has a terrific eye for desert landscapes as well as for the watering holes of the rich and the would-be-rich. This is a noirwith a difference, of course, because it’s shot in full color, thus depriving the film of the moody shadows that made 1940s cinema so evocative. In their place is Foley’s careful use of color, with its calculated splashes of crimson and blood-red. And the film’s big sex scene, carefully prepared for and long in coming, is far more explicit than anything the Forties might have been able to show. (Curiously, it’s male lead Jason Patric, not the stunning Rachel Ward, whose bare skin is on nearly-full display.) Patric, who also in 1990 would be featured as Lord Byron in Roger Corman’s regrettable return to directing, Frankenstein Unbound, makes a strong lead here, one both tender and volatile, smart and not-so-smart. And Ward’s character is perhaps more complex than most of the femmes fatales we know and love. But it’s Bruce Dern’s Uncle Bud I’ll long remember: a guy loathsome and yet almost lovable, a friendly fellow defined by greed, a true denizen of a film noir world.

July 9, 2021

It’s a Bird, It’s a Plane . . . It’s Clark Kent, Superstar

Larry Tye’s Superman: The High-Flying History of America’s Most Enduring Hero is not a biography in the usual sense. Most biographies are not about folks who hail from the dying planet Krypton. But there’s a good deal to say about an all-American superhero who was born in the depths of the Depression, spread his legend through the pages of comic books, graduated to movie serials and early television, then triumphed in big-screen blockbusters. Today, as a member of the Justice League (along with Batman and other larger-than-life types), he’s still going strong.

Tye, an eminent social historian who’s written biographies of everyone from Satchel Paige to Edward L. Bernays (inventor of the field of public relations), spends a fair amount of time on the not-always-super men behind Superman. In particular, he homes in on the careers of writer Jerry Siegel and artist Joe Schuster, two overgrown boys from Cleveland who launched the Man of Steel, gave him his secret Jewish roots, and ultimately lost control of their creation. But although Tye takes seriously indeed those who’ve invented, published, and merchandised Superman, he devotes himself equally to exploring the cultural implications of Superman’s popularity. As he sees it, we Americans need heroes, perhaps now more than ever, and Superman continues to fill the bill. His strength but also his vulnerability, his Boy Scout code of conduct, his fundamental sadness as the last of his kind, his need to grapple with the challenges posed by a dual identity—all this has attracted legions of ordinary fans, as well as such extraordinary ones as Jerry Seinfeld and basketball superstar Shaquille O’Neal.

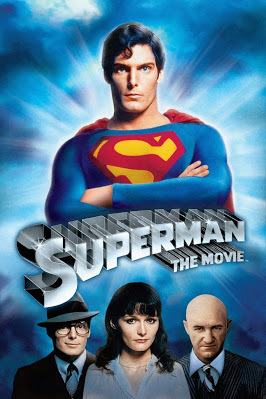

Long before Christopher Reeve there was a movie serial Superman, Kirk Alyn, as well as a TV Superman, George Reeves, who played the role starting in 1951. (Reeves’ apparent suicide in 1959 sparked ironic headlines as well as suggestions of foul play.) But the 1978 film directed by Richard Donner brought Superman into a new era of dazzling special effects. For the first time on screen, a Superman really conveyed the joy of flight. He also finally gave up on the idea of changing into his superhero tights in a telephone booth. By 1978, the traditional four-sided enclosure no longer sat on most street corners, so Christopher Reeve’s Clark Kent had to make do with a revolving door for a lightning-fast change of clothes.

Reeve is the heart and soul of Donner’s production. Frankly, I find the somber opening scenes on Krypton, which feature a silver-haired and silver-tongued Marlon Brando as baby Superman’s father, Jor-el, confusing and dull. The Kansas section of the film, in which the young child adopted by the Kents grows to be a sad and lonely young man, is sweet but by no means inspiring. But then we’re in Metropolis (aka New York City) where dweebish reporter Clark Kent metamorphoses into a swashbuckling superhero. When cast, Reeve was known as an actor, not a body-builder. He was 6’4” and handsome, but needed to add 30 pounds of muscle to fill out his spandex suit. As a trained stage performer he brought screwball comedy chops both to his portrait of the bumbling Clark and of the honest, bashful Superman. In courting Margot Kidder’s plucky Lois Lane, he is charmingly boyish, as when he admits that his super-sight tells him that her undies are pink. Then, deliberately emulating a young Cary Grant type, he slumps his shoulders, compresses his spine, raises his vocal pitch, and changes the part in his hair to become a Clark Kent whom even a smart gal like Lois wouldn’t recognize as her own personal superstar.

This post is, in part, a tribute to the late Richard Donner, who left us on July 5. May he rest in peace.

July 6, 2021

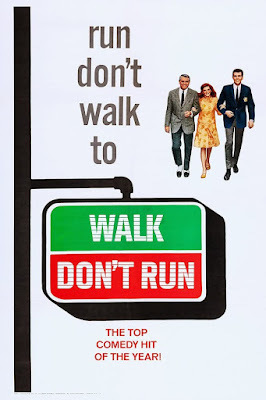

Great Balls of Fire! (Barbara Stanwyck Meets Gary Cooper. and Sparks Fly)

There’s something about a patriotic holiday like 4th of July that makes me want to go back in time, at least when it comes to my movie-viewing. (It’s easy, on the day of our nation’s birth, to settle on the perfect audio choice: the classic—and still hilarious—1961 comedy album, Stan Freberg Presents The United States of America: The Early Years. But I digress.) This past weekend, when it came to picking a movie, I settled for a screwball comedy with a title that sounds like a fireworks display: 1941’s Ball of Fire. Frankly, this title has nothing to do with the story that unfolds onscreen. But it suggests a blaze of romantic fireworks, which this movie delivers in spades.

Ball of Fire has quite a pedigree. It was written by Charles Brackett and Billy Wilder, just before the latter decided it was time to start directing his own screenplays, resulting in such masterworks as Double Indemnity and The Lost Weekend. It was directed by Howard Hawks, coming off the sparkling His Girl Friday and the patriotic Sergeant York. On Sergeant York, the true-life story of a soft-spoken country boy who became a World War I hero, the leading role was played by Gary Cooper, who won an Oscar for his iconic strong-silent-type performance. In Ball of Fire, he would pivot to the comedic role of a naïve academic, Professor Bertram Potts. Also in 1941 the always-memorable Barbara Stanwyck was having a banner year, appearing in five films, including The Lady Eve and Meet John Doe, along with her sexy role as Sugarpuss O’Shea in Ball of Fire. With all this talent, plus a boat-load of memorable character actors like S.Z. Sakall and Oskar Homolka, the film proved to be a hit with both critics and the public. It was nominated for four Oscars (one for Stanwyck’s performance), and in 2016 was chosen for the National Film Registry.

So what’s this slight but very funny film all about? It’s part of a time-honored Hollywood genre in which a good-hearted but naïve young man is transformed through his interaction with a woman of the world. How curious! We know Hollywood (both then and now) to be a place where the sharks are predominantly male, and innocent young ladies proceed at their own risk. Still, viewers in the 1940s seemed to love movies (whether romantic comedy or film noir) in which the man is an innocent, someone who faces and succumbs to the dangers posed by a predatory dame. A comedy classic of this ilk is Preston Sturges’ The Lady Eve, in which it’s Henry Fonda, not Gary Cooper, who’s an unworldly academic falling prey to Stanwyck’s charms. The Lady Eve is a far more complicated movie than Ball of Fire, with a more ambiguous ending, and a film buff of my acquaintance vastly prefers it. Double Indemnity carries the same trope into darker territory, with patsy Fred MacMurray lured by Stanwyck (now a blondebombshell) into a deadly scheme for which he’ll ultimately take the fall. Clearly Stanwyck is a lady who shouldn’t be trusted . . . but Ball of Fire also hints at her softer side.

It’s said that one of the major influences on Ball of Fire is Snow White and the Seven Dwarves. Cooper’s character, you see, is a grammarian who – along with seven crochety scholars from various fields – is working on a ground-breaking new encyclopedia. All unmarried, they live together in a big house, pursuing their arcane research. Then Sugarpuss shows up and teaches them to dance the conga—and hilarity ensues.

Beverly in Movieland

- Beverly Gray's profile

- 10 followers