Beverly Gray's Blog: Beverly in Movieland, page 40

December 24, 2021

Send in the Crowns: Stephen Sondheim, King of Musical Theatre

“Not A Day Goes By” is the title of one of my favorite Sondheim ballads. This haunting tune doesn’t hail from one of the master’s greatest hits, like Into the Woods or Sweeney Todd. Instead it was introduced in a rare late-career flop, 1981’s Merrily We Roll Along. This is hardly among Sondheim’s most bravura shows: no murderers, no witches, no giants, no exploration of the history of modern art. Still, as a musical pinpointing what career success can do to a young composer, it perhaps may be one of his most personal. Or not: Sondheim doesn’t easily give himself away.

I start with “Not A Day Goes By” because I’m guessing that every single day there is someone, somewhere, parsing a Sondheim lyric or humming a Sondheim tune. I know that, especially since his recent death at age 91, my own head is full of them – “Pretty Women,” “The Miller’s Son,” “Children and Art,” “Someone in a Tree,” “No One is Alone.” And Sondheim’s lyrics (along with Leonard Bernstein’s tunes) are an integral part of West Side Story, which is now enjoying its second go-round as a major motion picture.

I’ve just discovered that Merrily We Roll Around too has been tapped for the movies, with Richard Linklater set to adapt and direct the Sondheim/George Furth play. Ben Platt (of Dear Evan Hansen fame) and Beanie Feldstein are solid choices to play two of the story’s three central characters, and I’m hoping for the best. But this is a play in which chronology works backward, and Linklater (who famously made Boyhood over eleven years to capture the ageing process) apparently wants to shoot off and on for two decades, so don’t expect a premiere anytime soon.

For a man devoted to the Broadway stage, Sondheim always loved movies. That’s why some of the best of his musicals have—successfully or not—ended up on screen. I don’t have much to say about the 1977 film adaptation of A Little Night Music, a musical that was itself based on an Ingmar Bergman film, Smiles of a Summer Night. Even though it was distributed (incredibly enough) by my former boss, Roger Corman, I haven’t seen it. But the snatches I’ve found on YouTube of Elizabeth Taylor, as the glamorous Desiree Arnfeldt, singing Sondheim’s indelible “Send in the Clowns” are hard to take. It’s not the singing (the song was originally crafted for non-singer Glynis Johns) that’s the problem. But Taylor is so stiff!

More recently (2007), Tim Burton directed an all-star version of perhaps Sondheim’s most popular musical, the gruesome but somehow delightful Sweeney Todd: The Demon Barber of Fleet Street. Featured in the cast of this London-set extravaganza are some of Britain’s finest: Alan Rickman as the evil Judge Turpin, Timothy Spall as his sinister sidekick, Beadle Banford, and Sacha Baron Cohen as the huckster Pirelli. Burton’s own love interest, Helena Bonham Carter, made a suitably bedraggled Mrs. Lovett. But the title role went to an American, Johnny Depp, whose generally dour demeanor worked surprisingly well for the haunted barber. (I’ve heard his performance as Sweeney was one of Sondheim’s favorites.) The most memorable moment for me? The “By the Sea” fantasy number, in which Sweeney sits with Mrs. Lovett on the beach at Brighton, still wearing his black suit and his sour expression.

Then there’s 2014’s lovingly adapted Into the Woods, for which Sondheim and book writer James Lapine approved all plot changes. In the big ensemble cast, I’ll remember most fondly Meryl Streep (The Witch), Anna Kendrick (Cinderella), and Emily Blunt as the plucky Baker’s Wife.

December 21, 2021

Tom Nolan: From Sound Stage to Page

Seeing to expand my knowledge of Billy Wilder’s directing career, I sat down to watch a flick that raised many hackles when first released in 1964. Kiss Me, Stupid, in which Dean Martin canoodles with a presumably happy housewife and Kim Novak plays a lady of (shall we say?) loose morals, was condemned by the Catholic Church and accused by Hedda Hopper of being a stag film. It’s hardly that, but it’s a rather sour farce in which a small-town music teacher (Ray Walston) is so insanely jealous of his pretty wife that he disrupts his household arrangements when a swingin’ Las Vegas star with car trouble rents his spare bedroom for the night. Early in the film, there’s a scene in which a gawky kid bikes over for his piano lesson, only to be accused of having designs on Walston’s spouse. Appearing in that hilarious scene is a fresh-faced 16-year-old named Tommy Nolan. Could it be? Yes, it could.

The Tom Nolan I know doesn’t have much hair, and he’s much older than 16. He’s had a major career as a journalist and author, earning plaudits especially for a biography of mystery writer Ross MacDonald that was published in 2015. I had no idea that he’d been a showbiz kid until I showed up at a gathering of fans of TV and movie westerns. To my great surprise, Tom was introduced from the stage as the one-time child star of something called Buckskin. This was a 1958 series about a boy and his widowed mom who run a boarding-house in frontier Montana, circa 1880. Though it didn’t last long, the characters were popular enough to launch a comic-book line.

None of this was what young Bernard Girouard anticipated when he moved from Montreal to the San Fernando Valley with his family at age 4. He had always liked tap-dancing and playing the piano, and once there was a TV set at home he started to wonder, “Maybe there was a place for me inside that box.” Through a lucky break he was signed by an agent who specialized in kids, and by 5 he was appearing on the Hallmark Hall of Fame in a costume drama, playing the Prince of Wales to Sarah Churchill’s Jane Seymour. For years he never stopped working, first as Butch Bernard and then (for Buckskin) as Tommy Nolan. Later, at UCLA, he tried reverting to his birth name, but it didn’t take, because “I wasn’t that person anymore.”

Tom played Tom Ewell’s son in the Billy Wilder (and Marilyn Monroe) comedy classic, The Seven Year Itch. Almost a decade later, when Wilder was casting Kiss Me, Stupid, Tom got a second chance to be directed by the master. The role of the music teacher originally went to Peter Sellers, the troubled genius whom Tom describes as “the funniest person I had ever encountered.” By then, he had played opposite such comic stars as Ed Wynn, Jack Benny, and Jerry Lewis. But “Sellers's comic presence was so intense I had to cheat my glance to the side; I couldn't look him straight in the face for fear of breaking up at his merest raised eyebrow or chin-tilt.” Unfortunately Sellers, enjoying a brand-new young bride and some controlled substances, suffered a massive heart attack mid-production, and was replaced by Walston. Which meant Tom had to shoot his scenes again with a new leading man. Tom remembers Walston as “courteous, well-prepared, professional and capable. But when we did our two scenes together, I had no trouble looking him right in the eye.”

December 16, 2021

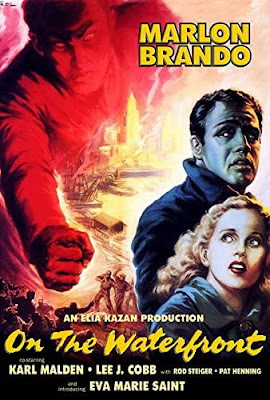

Soaring Over the Waterfront with Marlon Brando and Company

The opening credits of On the Waterfront are punctuated by the sound of a solo trumpet played in a minor key. It’s Leonard Bernstein at his bluesy finest: this was the maestro’s only original film score, and it earned him one of the film’s 12 Oscar nominations. A later, more gentle track from that Bernstein score is called “Dead Pigeons.” That’s an odd-sounding name for a musical interlude, but it’s one that fits this particular story nicely. On the Waterfront is based on a Pulitzer-Prize-winning series, published in the New York Sun, chronicling union corruption at the local dockyards. The film version (set on the Hoboken docks) is full of ships, and cargo, and tough guys with fiery tempers. But its plot and some of its key images involve pigeons, the kind that slum kids raise on the roofs of their buildings, showing tenderness to dumb creatures that will one day soar high above them and their grim little lives.

Pigeons? Think of the metaphorical implications of being a stool pigeon, one of the most hated types in the gangster universe. The men at the dockyards well know they’re required to be “D & D.” This stands for ”deaf and dumb”: though the union bosses are ripping them off at every turn, few of them dare complain. When one brave (or foolhardy) idealist shows a willingness to testify in front of a governmental crime commission, he’s lured to his death. That death starts things happening: the gutsy local priest gets involved, as does the dead man’s genteel sister, raised by nuns to be a school teacher but now determined to fight for her brother’s memory. But the focal point of the story is Terry Malloy, played by Marlon Brando in the role that sealed his reputation as the best actor of his time. Terry, once a promising young boxer, is now a favorite of union boss Johnny Friendly, who runs the docks with an iron fist. At the start of the film Terry is a cog in a smoothly-running machine. But his involvement in Joey Doyle’s murder and his growing interest in Doyle’s sister Edie slowly convince him to rethink his life. It’s a film that puts the spotlight on an evolving hero, though the courage shown here is strictly devoid of phony sentimentality.

This is the sort of bracing movie in which everything works: a smartly told story, vivid black & white cinematography, that Bernstein score. Hence the film collected 8 Oscars, in a year that saw such major successes as The Caine Mutiny, A Star is Born, and the charming Seven Brides for Seven Brothers. In addition to Best Picture, On the Waterfront won for its direction (Elia Kazan), its screenplay (Budd Schulberg), and the performance of Eva Marie Saint in her debut film. Brando deservedly received the Best Actor statuette, and -- yes! –walked to the stage, wearing a tuxedo, to gratefully accept it from Bette Davis. No fewer than three actors from On the Waterfront were nominated in support: Karl Malden as the priest, Lee J. Cobb as the corrupt union boss, Rod Steiger as Brando’s older brother, to whom he famously muses, “I coulda been a contender.” .

It’s worth noting that when the film was released, in 1954, the U.S. was still caught up in the McCarthy Era, So the idea of testifying in front of a government committee took on a certain coloration, especially because director Elia Kazan had famously named names before the House Un-American Activities Committee two years earlier. This film’s focus, though, is not politics but honor.

December 14, 2021

A Powerful “Power of the Dog”

Jane Campion’s new The Power of the Dog, can fairly be described as a mystery. Which by no means suggests that it’s a classic whodunit, with dark deeds committed early on and the perpetrator unmasked just before the lights come up. There’s certainly darkness in this movie, but emphasis in The Power of the Dog is squarely on the mystery of the human soul. As in Campion’s long-ago 1993 triumph, The Piano, the new film is peopled by characters who act in ways we don’t always understand. Two moviegoers can come away from it with entirely different perspectives on what just happened on screen. My filmgoing companion turned to me afterwards and said, “Well, I didn’t see that coming.” And I admit that my own first thoughts were quite different from the well-reasoned conclusion he’d reached. There’s no shame in needing to watch The Power of the Dog more than once. This is a film that offers huge rewards to those paying close attention.

Partly that’s because Campion is such a visual stylist. Without ever becoming heavy-handed, she draws our attention to places and objects that have their own quiet significance in the tale being told. As in The Piano, the landscape is definitely part of the story. In the earlier film it was the wild New Zealand coastline. Here it’s New Zealand again, standing in for the chilly plains and rocky hills of Montana, circa 1920. The realistic close-ups of cowboys going about their daily work move the film squarely into the Western genre, but there’s an effective juxtaposition with the film’s traces of modernity, including the rare automobile and flapper-length skirts. The clash between past and present is essential to the story being told, somewhat as in Kirk Douglas’s fascinating Lonely are the Brave.

But things, as well as places and time-frames, also have their significance. I don’t believe an at-home viewing on a television screen can fully introduce us to inanimate objects that, through dramatic closeups, play a key part in the unfolding drama. Hand-made paper flowers, a braided leather rope, a monogramed scarf, gleaming white tennis sneakers—these mundane items become hugely important over the course of the story. Equally important is the mysterious title that only makes its meaning felt at the film’s very end. Its source is a Biblical passage (Psalm 22:20 --“Rescue my soul from the sword, my essence from the grip of the dog”) that at first seems unrelated to the matters at hand. Certainly, this is not a dog story. It’s only in the context of all that’s gone before that we can find a shred of meaning in these mysterious but evocative words.

I’ve stalled in mentioning the film’s chief actors, all of whom make an indelible impression. The protean Benedict Cumberbatch is front and center, playing Phil Burbank, a roughneck type we don’t know whether to hate or pity. Jesse Plemons (so ominous in Breaking Bad) here conveys a very different type, the gentle, civilized brother who becomes the object of Phil’s ongoing scorn. The always welcome Kirsten Dunst sinks her teeth into the role of the new wife, fragile but ultimately sturdy. If all of the above sounds like something from Steinbeck (East of Eden) or maybe Tennessee Williams, Campion has a few surprises up her sleeve. I also need to mention a relative newcomer to American films, Australian Kodi Smit-McPhee, as Dunst’s gawky, introspective son. In a L.A. Times interview, Smit-McPhee gives his own clearcut view of the film’s ambiguous ending. If you read it prior to seeing this mesmerizing movie, you’ll be sorry.

December 10, 2021

Catherine Corman: Avant-Garde Chip Off the Old Block

I wasn’t part of the Roger Corman universe when his daughter Catherine was born. By the time the first Corman child made her appearance, I had moved on to other things. But my spies at New World Pictures described for me the excitement caused by her arrival on May 2, 1975. An announcement in Boxoffice ten days later listed the newborn’s name as Aimee. This error probably reflects the long, arduous process that went into choosing a name for each Corman offspring. For weeks after the birth, the office staff was polled about possible choices for the new arrival. I’m told that when the name Catherine Corman was finally unveiled, someone joked that it would look good on a marquee. At this Roger turned grave, then said, “Let’s think of it as a working title.”

Later, at Roger’s Concorde-New Horizons I had no personal contact with Catherine over the years, even though she had a featured role in his return to directing, Frankenstein Unbound. (She did a creditable job as an unfortunate servant girl, though it must have seemed strange to Roger to film his fourteen-year-old daughter being hanged.) But as the end of her high school years approached, I found myself caught up in Catherine’s college plans. More than once Roger asked me, “as a friend,” to critique her class essays and college application forms, by way of giving her every possible advantage when it came to being accepted by a prestige school. I doubt she knew of my involvement, and—quite honestly—she didn’t need my help. Catherine was a bright and serious young lady, graduating from a high-powered prep school, and her celebrated family hardly hurt her chances for success. When she was accepted at both Harvard and Stanford (Roger’s own alma mater), her proud papa gathered office alumni of both of these schools, who were tasked with convincing her of their relative merits. (Which college did Roger himself prefer? This changed from day to day, but he alternately felt strongly about each of the two options.)

Catherine ultimately chose Harvard, and began to focus on highly intellectual fine-arts projects blending literature and photography. Not for her the kinds of work that had made her father famous: sexy and gruesome action thrillers and Edgar Allan Poe adaptations. Her published works include the collage-like Joseph Cornell’s Dream, a photographic tour of Philip Marlowe’s L.A. at high noon (Daylight Noir), and a verse-and-image collection called Romanticism that was nominated for a Pushcart Prize. At a young age she was entrusted with the key role of production manager on a Corman film shot in India, but her own filmmaking forays have been far less commercial than those of her father Roger and her mother, producer Julie Corman. In the last week, I’ve spotted several news stories about her latest cinematic endeavor: a 4-minute short film shot on Super 8, reflecting the writings of Nobel laureate Patrick Modiano. The moody short, called Lost Horizon, was somewhat of a pandemic home-movie project, featuring both her famous father and her sister, Mary Tessa. It’s been long-listed for an Oscar, and she promises additional films to come.

Life within the Corman family has been famously turbulent of late, with Catherine’s two brothers acrimoniously suing their parents in 2009. But Catherine’s always been known as the family peacemaker, working hard to smooth over tensions. I love the fact that she’s always quick to credit her 95-year-old dad, whose own latest project is a re-tread of Slumber Party Massacre, for teaching her to love art. Yes, her name may find itself on a marquee sometime soon.

December 7, 2021

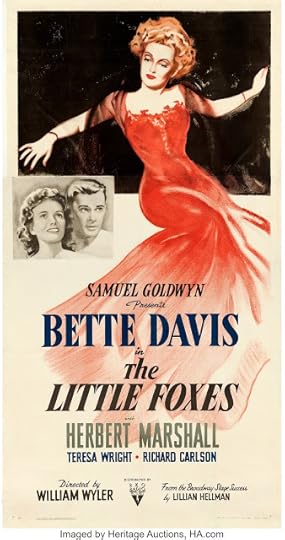

A Little Look at “The Little Foxes”

It may be because of The Little Foxes that, after the screen mega-triumph of The Graduate, director Mike Nichols never again worked with the film’s breakout star, Dustin Hoffman. Lawrence Turman, who produced The Graduate, has a faint recollection of the moment when Nichols and Hoffman parted ways. It seems that once The Graduate was complete, Nichols signed on to direct an all-star revival of the Lillian Hellman drama at Lincoln Center. In the leading role--that of a scheming woman determined to make a financial killing at her brothers’ expense—would be Mrs. Robinson herself, Anne Bancroft. Others in the cast included Margaret Leighton, E.G. Marshall, and George C. Scott. The production, enthusiastically received, soon moved to Broadway, racking up over 100 performances. If Larry Turman’s memory is correct, Dustin Hoffman was asked to take part, but turned down the opportunity. Turman mused to me that Nichols, despite a tough exterior, could sometimes be intensely vulnerable. So the turn-down by Hoffman “might have engendered Mike’s frustration, anger, hostility, who knows what.”

It may be because of The Little Foxes that, after the screen mega-triumph of The Graduate, director Mike Nichols never again worked with the film’s breakout star, Dustin Hoffman. Lawrence Turman, who produced The Graduate, has a faint recollection of the moment when Nichols and Hoffman parted ways. It seems that once The Graduate was complete, Nichols signed on to direct an all-star revival of the Lillian Hellman drama at Lincoln Center. In the leading role--that of a scheming woman determined to make a financial killing at her brothers’ expense—would be Mrs. Robinson herself, Anne Bancroft. Others in the cast included Margaret Leighton, E.G. Marshall, and George C. Scott. The production, enthusiastically received, soon moved to Broadway, racking up over 100 performances. If Larry Turman’s memory is correct, Dustin Hoffman was asked to take part, but turned down the opportunity. Turman mused to me that Nichols, despite a tough exterior, could sometimes be intensely vulnerable. So the turn-down by Hoffman “might have engendered Mike’s frustration, anger, hostility, who knows what.” That’s pure speculation, of course. But we know that Lillian Hellman’s The Little Foxes has been a stage perennial since it debuted on Broadway in 1939, headed by Tallulah Bankhead. There’ve been five Broadway productions in all, the last in 2017, with Laura Linney and Cynthia Nixon alternating in the roles of the cold-blooded Regina Giddens and her fragile sister-in-law, Birdie Hubbard. When the play was transformed into a film in 1941, most of the Broadway cast held onto their roles. But film director William Wyler decided that the star of two of his earlier film triumphs should anchor the movie. So Bette Davis, a great admirer of Bankhead’s stage performance, wrestled with ways to make the role her own. Though Bankhead had hinted that Regina was a victim as well as a villain, Davis went for the jugular. It was apparently her idea (decried by Wyler) to coat her face in white powder to give her character a spectral, almost Kabuki-like, look. The result: a woman you love to hate.

Seeing the film for the first time, I was delighted by its old-fashioned craftsmanship. Having recently suffered through some arty contemporary dramas in which you’re never quite sure who’s doing what or why, I appreciated the solidity of the film’s sets and performances. The Little Foxes, which reflexes the grotesque money-grubbing in Hellman’s childhood home, takes place in a small Southern town where everyone is always impeccably dressed and groomed. The screen adaptation (by Hellman herself, with some Dorothy Parker additions), is highly literate, and does a good job of breaking free of the gussied-up parlor that’s the play’s single setting. Instead we see something of the town, something of Regina’s shady veranda, something of the train that takes daughter Alexandra to fetch her father home as a way to serve Regina’s devious purposes. As for the cinematography, suffice it to say that the camera team was led by Gregg Toland, who shot Citizen Kane.

Though the film is definitely a period piece, made 80 years ago to reflect small-town life at the start of the 20th century, some aspects of it still seem current. Near the very end, when Regina has conclusively one-upped the smarter of her two brothers, he bears no grudge. Instead Charles Dingle as Ben Hubbard essentially congratulates Regina, saying, “The world's open for people like you and me. There's thousands of us all over the world. We'll own the country some day. They won't try to stop us. We'll get along.” I wish those words didn’t sound quite so contemporary.

December 2, 2021

“Cheyenne Autumn”: John Ford’s Native American Elegy

In Hollywood westerns, you can always count on Indians getting the short end of the stick. They’ve traditionally been portrayed as blood-thirsty savages out to threaten heroic white men (and their women), or else as ignorant hangers-on who loaf on the fringes of western towns. Late in his career, the great John Ford sought to rectify that. Ford had directed such classic westerns as 1939’s Stagecoach, in which we root for an eclectic group of travelers who face the threat of Apaches on the warpath. Later Ford films, like those in his so-called Cavalry Trilogy, show more sympathy for the Native American perspective, yet all continue to focus chiefly on white characters who wrestle with military strategies and romantic entanglements. But Ford’s close personal ties to the Navajo Nation (he shot many of his films in Monument Valley, with full cooperation from the native residents) led him to seek to dramatize a story of the U.S. government’s failure to keep its promises to Native American populations.

In Cheyenne Autumn (1964), Ford took on what’s been called the Northern Cheyenne Exodus of 1878-1879. Historically, following the Battle of Little Big Horn, a number of Cheyenne tribes were forced by the U.S. military to trek from their tribal lands in Wyoming to a dismal reservation in Oklahoma. Hungry and dispirited in their new surroundings, the Cheyenne set out to return home, with U.S. Army troops in hot pursuit. Ford’s version, which ended up playing fast and loose with the historical record, was not entirely the film he hoped to make.

I’m relying here on the words of my colleague, film historian Joseph McBride, who knew Ford and wrote the highly regarded Searching for John Ford: A Life. In an invaluable collection called Two Cheers for Hollywood: Joseph McBride on Movies, Joe broaches Ford’s attitudes toward Native American culture. Ford attributed much of his warmth toward native tribes to his own proud Irish heritage: “My sympathy is all with the Indians. . . . More than having received Oscars, what counts for me is having been made a blood brother of various Indian tribes. . . . Who better than an Irishman could understand the Indians, while still being stirred by the tales of the U.S. Cavalry? We were on both sides of the epic.”

In making Cheyenne Autumn, Ford aimed to shoot in sober black & white, using subtitles for authentic Native American dialogue, and casting actors of genuine Indian descent. But to get financing, he had to agree to a full-color wide-screen epic full of stars like Edward G. Robinson and (in an odd comic detour from the main plotline) James Stewart as Wyatt Earp. The major Indian roles were played by Anglos and Mexicans (Ricardo Montalban, Dolores del Rio), with Italian-American Sal Mineo in a prominent part. The $6.6 million budget was the highest of Ford’s career, and led to a box-office flop.

McBride, well aware of the movie’s failings, admits that Ford, for all his emotional connection to the Native American tribal lifestyle, was never able to truly get inside his Indian characters. In this film, says McBride, “Ford views the Cheyenne as symbols rather than people.” Still, he makes a good case for Cheyenne Autumn as “a work of visual poetry,” majestically evoking a tragedy of the Old West. For me, this is best seen very early in the film, as the Cheyenne quietly assemble at a military outpost, then stand stock-still to wait – for hours –to plead their case before a Congressional delegation that never arrives Their dignity in this ordeal never fails them. Visual poetry indeed.

November 30, 2021

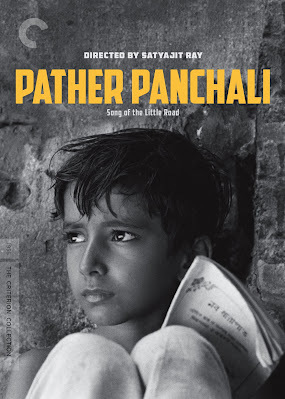

The Simple Gifts of “Pather Panchali”

The first time I saw Pather Panchali, it was under unusual circumstances. I was a student in Tokyo, having a wonderful time but missing the chance to see movies that were not standard Hollywood fare. In a basement in Shinjuku I happened upon a tiny movie house that alternated between soft-core porn and the classics of world cinema. That’s where I’d go for my foreign film fix, taking care to choose movies made in the English language. Not that I’m opposed to reading subtitles—but these were in Japanese and therefore not of much help.

One day, though, I couldn’t resist buying a ticket for the much-acclaimed first feature by the great Indian director, Satyajit Ray. This 1955 film, shot in Bengali using largely amateur actors, would later be near the top of many global “best picture” lists, and would lead to two additional features, making up what’s been called the Apu Trilogy. Pather Panchali (meaning “Song of the Little Road”) boasts gorgeous cinematography and a haunting score by a young sitar player named Ravi Shankar. I couldn’t miss the fact that it was about an impoverished family in rural Bengal, desperately hanging on despite the frequent absences of the man of the house. Though I sat in that basement cinema more than fifty years ago, I have a clear recollection of one of the most dramatic sequences, in which rain pelts the tumbledown shack while a mother – her eyes haunted by worry -- crouches at the bedside of her ailing child.

Pather Panchali is a strongly visual film, playing on emotions that are universal. But of course, without the help of language, there was so much nuance that I missed. That’s why I leaped at the chance to see a beautifully restored print in the sumptuous David Geffen Theatre at L.A.’s new Academy Museum. The museum is celebrating, in the first months of its existence, the work it has put into locating and restoring the entire Ray canon. This work is particularly noteworthy since the master prints of the entire Apu Trilogy came close to being destroyed in a warehouse fire.

There’s no question that Pather Panchali seems long and slow. It is not without humor, but its basic tone is poignant. This is the story of a scholarly father who in another culture might be called a luftmensch: he has his dreams of a better life, but can’t seem to bring them to fruition, which is why he is mostly absent, scrounging in the big city for work. Meanwhile, the mother of the family desperately hangs on. There’s a sprightly daughter with wealthier friends she can’t help envying, and a charming little son, Apu, full of good-hearted mischief. And there’s a whole gallery of other local characters, including the irascible schoolmaster, the always-suspicious neighbor, the ascetic collecting alms, and a wizened old “auntie” who has taken up residence with the family and is not above commandeering what food there is on hand. We see others in this rural environment who can be petty and hard-hearted, but mostly come through when the chips are thoroughly down.

Ray, with a background in art and advertising, turned to filmmaking after he first saw an Italian neo-realist classic, Bicycle Thieves (1948) during a trip to London. For those familiar with India’s Bollywood tradition, with its garish colors and non-stop musical numbers, Pather Panchali is a revelation. Shot in rich black & white, it is fully about the poetry of real life. Those quiet shots of waterbugs scooting leisurely across a local pond: daily existence doesn’t get much more beautiful.

November 25, 2021

Seduced by Howard Hughes

It’s natural -- especially when you come from a family of engineers -– to think of Howard Hughes mostly in terms of aircraft. And of course there’s the latter-day Hughes, a crazy old man whose fortune couldn’t shield him from mental illness and a lonely death. But Hughes’ life (1905-1976) was intertwined with the history of the Hollywood movie industry. As a dashing young millionaire, he became determined to be a force in the world of entertainment.

Starting in 1926, Hughes put his considerable money behind films that were nominated for, and sometimes won, Academy Awards. Most notably, he sank about $3 million (and three years of his life) into a pet project, the World War I aerial drama, Hell’s Angels. The film, which was nominated for Best Cinematography, launched the career of Jean Harlow, whom Hughes chose to outfit in slinky gowns of his own devising. But despite a massive publicity campaign, Hell’s Angelscould not recoup its then-outlandish expenses. There were human costs too. The spectacular aerial stunt work led to the deaths of three aviators and a mechanic. And Hughes himself, as a participant in some of the stunts, crashed his plane and suffered a fractured skull, the first of many dramatic injuries that doubtless contributed to his strange, twisted view of life.

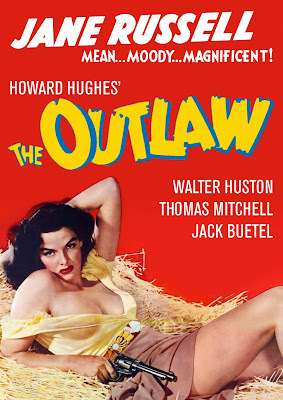

In 2018, a new book on Hughes’ movie years made its appearance. Called Seduction:Sex, Lies, and Stardom in Howard Hughes’ Hollywood, this heavily researched volume was written by Karina Longworth, the Angeleno behind You Must Remember This, a popular podcast that chronicles the secret history of the old studio system. Longworth does not neglect Hughes the industrialist, but her focus is on Hughes’ interaction with Hollywood, especially its women. There are lots of colorful details about his romances with Katharine Hepburn (who praised him as a lover), Ginger Rogers, Ava Gardner, and other celebrated lovelies. Much time is spent, needless to say, on his relationship with the very young, very well endowed Jane Russell: while guiding the production of The Outlaw, in which she plays a half-breed Mexican beauty sexually assaulted in a hayloft by Billy the Kid, Hughes famously engineered a brassiere that would dramatically emphasize her two most prominent assets. Russell’s relationship with Hughes was to complicate her later marriage to a prominent football star. While moving in and out of a leadership role at RKO Pictures, Hughes kept Russell under personal contract for decades.

I learned, in passing, about many remarkable Hollywood women. One was Ida Lupino, admired today as one of the few American females able to break into directing, but also apparently someone who fostered her own career success by secretly cooperating with the House Un-American Activities Committee during the dark days of the Blacklist. Another was Terry Moore, a blonde and perky devout Mormon (now 92), who still seems convinced that she and Hughes contracted a secret marriage in 1949. (She has since had 5 other husbands.) Most disturbing, though, is Longworth’s recounting of the way the middle-aged Hughes courted pretty and very young women, scouting them out in their hometowns, enlisting the support of their starstruck mothers, and dangling before them the prospects of a movie career. Once they came to Hollywood, Hughes would ensconce them in hotel suites or bungalows, provide them with cars and drivers, enroll them in acting and dance classes, then occasionally drop by to sample their charms. No surprise: few ever appeared in movies at all. But Hughes did, as portrayed by Jason Robards, in 1980s sad and hilarious Melvin and Howard.

November 23, 2021

Tessa Thompson: “Passing” With Honors

It’s been a while since I used to give Tessa Thompson lifts home from Santa Monica High School. (She and my son were in the same drama class.) That particular teacher, known to one and all as Doc Ford, had helped launch thc careers of several stage and screen performers, who went on to build careers on film, on TV, and in the cast of Hamilton. Honestly, I would never have picked Tessa as the one most likely to succeed. She was lively and cute, just right for an ingenue part in A Midsummer Night’s Dream and as the ballet-dancing daughter in Kaufman and Hart’s zany comedy classic, You Can’t Take It With You. I heard she was fiercely committed to her craft, but I never anticipated her as a future award winner. Or, for that matter, on the cover of Time magazine, as she was a few years back.

I haven’t seen everything in Tessa’s filmography, but up until now there’s been a strong accent on romance and comedy. She had a girlfriend role in the Creed films (starting in 2015), and was a sassy college trouble-maker in Dear White People (2014). Her big action parts, as Valkyrie in Marvel’s Thor: Ragnarok (2017) and as Agent M in Men in Black: International (2019), allowed her to do a lot of butt-kicking, while also exchanging quips with handsome leading men. She has also voiced the female lead in a live re-make of Lady and the Tramp that features (yup!) real dogs. And in 2020 she collected an Emmy nomination as the heroine of a schmaltzy romantic TV film, Sylvie’s Love. The one historic role she’s played, as civil rights activist Diane Nash in Selma, was something of a blink-or-you’ll-miss-it cameo.

No one is likely to overlook Tessa in Passing. This 2021 film, based on an incendiary 1929 novel, was written, produced, and directed by Rebecca Hall, the actress-daughter of famed British director Peter Hall. Her mother was the operatic soprano Maria Ewing, whose tangled family tree made Rebecca take great interest in the subject of Black women who dare to pass for white. This is Hall’s first film as a director, but certainly not her last: her artistic self-assurance is evidence of her talent.

The film, set in 1920s New York, requires two Black actresses with light skin, both of whom could theoretically succeed in “passing.” The briefer, showier part is that of Clare: she has dyed her bobbed hair blonde and assumed a madcap air that has won her a white husband who’s an unrepentant racist. This role is played by Ruth Negga, the Ethiopian/Irish actress who was a well-deserved Oscar nominee for Loving. She is the sparkplug who makes the story happen, but we can only guess at what’s going on inside her. By contrast, Tessa plays Irene, the apparently contented wife of a socially prominent Black doctor. The Harlem brownstone where they’re raising their sons is a showplace, and she’s a pillar of New York’s African-American community. It’s a role that requires of Tessa a new maturity I had not previously seen. She plays not a vibrant, sexy young lady but rather a serious, sensitive woman. Moreover her part is largely reactive, rather than active: the camera is frequently on her as she absorbs and contemplates the life of the dazzling blonde—her childhood friend—who is now in many ways her opposite.

Hall has chosen to underscore the racial issues raised in Passing by filming in black & white, lingering on floating shadows in ambiguous shades of grey. Yes, it’s arty, but it packs a wallop..

Beverly in Movieland

- Beverly Gray's profile

- 10 followers