Beverly Gray's Blog: Beverly in Movieland, page 36

May 5, 2022

Children of a Lesser God”: The Deaf Speak Out

CODA, a small film about a deaf family in small-town Massachusetts, surprised the experts by winning Best Picture at this year’s Oscar ceremony. But CODA (the title stands for “Child of Deaf Adults”) is hardly the first award-winning American film that has featured non-hearing characters.

Johnny Belinda was a schmaltzy melodrama that created quite a stir in 1948 for its then-bold depiction of rape and its consequences. It was nominated for a slew of Oscars, including Best Picture, and star Jane Wyman took home a golden statuette for her portrayal of what was then called a “deaf-mute.” It would not be the last time a hearing actress was lauded for portraying someone unable to hear. The film version of William Gibson’s stage hit, The Miracle Worker, dramatizing the early life of Helen Keller, was one of 1962’s greatest hits. It garnered two Oscars. One was for Anne Bancroft as Keller’s teacher, Annie Sullivan. The second, in the “supporting” category, was for young Patty Duke (barely 16), who vividly portrayed Keller as a savage young girl unable to see or hear until the great breakthrough moment when she discovers that water “has a name.” Duke, who had also starred in the stage production of Gibson’s play, was of course perfectly capable of seeing and hearing. Frankly, it’s hard to imagine someone contending with the physical and mental rigors of this role, especially on a typical eight-performances-a-week Broadway schedule, without being able to communicate easily with her director and her fellow thespians. A blind actress playing young Helen Keller still seems impossible. But a DEAF actress—who knows?

A change in thinking is afoot. I’m by no means claiming that all members of the deaf community are inherently talented actors. But those fluent in American Sign Language are grounded in what we might call acting techniques. This language is not conveyed simply through spelling with the fingers. Emphatic gestures and easily-read facial expressions are part of the whole communication system employed by the deaf.

Children of a Lesser God, which ran on Broadway from 1980 to 1982 after being launched at L.A.’s Mark Taper Forum, is a play by Mark Medoff that directly tackles the gap between the deaf and the hearing community. The play won three Tony Awards, for Best Play, for Best Actor (John Rubenstein) and for Best Actress (Phyllis Frelich). In many ways it is Frelich’s own story, reflecting her struggles as a deaf woman to reconcile with an environment that demands that she learn, however awkwardly, to voice words in English. What gives the play power is that it’s an unconventional love story, in which a hearing man who teaches deaf youngsters to speak falls for a vibrant but angry young woman who refuses to set aside her well-honed ASL skills in order to join the wider world.

When the play was acquired by Hollywood, playwright Medoff was still involved, but the context of the story changed, removing a strand involving a lawsuit that would have required deaf children to be instructed solely by deaf teachers. Yet the central issue remained: that of deaf individuals fearing they’ll lose their unique culture if required to communicate in ways that are not natural to them. The 1986 film was nominated for Best Picture and 5 other honors. Male lead William Hurt, whose recent death I mourn, makes a sympathetic leading man, both sensitive enough and quirky enough to be believable in a challenging role. But his opposite number, Marlee Matlin made history as the first deaf performer to win an Oscar. Now, thanks to CODA’s Troy Kotsur, she’s not alone.

May 3, 2022

A Love Letter to “Terms of Endearment”

Longtime fans of Shirley MacLaine know she’s had something of a charmed career. As a young Broadway dancer in a hit musical called The Pajana Game, she understudied star Carol Haney, who was known to have an iron constitution and a strong will. The word was that she never missed performances. But then she injured her leg . . . and when Shirley took over, there was a Hollywood talent scout in the audience. Her very first film, in 1955, was the female lead in a rare Alfred Hitchcock comedy, The Trouble with Harry. Three years later, she was cast in the year’s biggest blockbuster, Around the World in 80 Days, in the unlikely role of an Indian princess rescued from her husband’s funeral pyre. (In those days, there was not much of a move toward ethnic authenticity in casting.)

From the first she tended to be cast as kooks, innocents, and mid-century versions of manic pixie dreamgirls. (This was perhaps not surprising, given her off-center spiritual views, which include firm beliefs in reincarnation, space aliens, and other unconventional lifeforms.) Billy Wilder took full advantage of her winsome presence in The Apartment, and later cast her again with Jack Lemmon in the frothy Irma la Douce. There she played a good-hearted prostitute, a character somewhat akin to a later signature role, that of Charity Hope Valentine in the film version of Neil Simon’s musical, Sweet Charity. (In Sweet Charity, she’s officially a taxi-dancer, but it’s based on Fellini’s earthier TheNights of Cabiria, and in both cases she’s a girl whom guys really shouldn’t bring home to Mama.)

All that was in the Sixties. It took until 1983 to reveal to audiences MacLaine’s full dramatic range. As wealthy Houston matriarch Aurora Greenway in Terms of Endearment (adapted by James L. Brooks from a Larry McMurtry novel), she’s hardly just an adorable pushover. Sharp-tongued and self-possessed, she rules her small domain with an iron fist. Of course this is crazy-making for her free-spirited daughter, Emma (Debra Winger): Aurora even ducks out of her only child’s wedding at the very last moment because she doesn’t care for the bridegroom. There’s a lot of love (and a lot of sex) in this story. Emma can barely keep her hands off her new husband (Jeff Daniels), a college professor with a roving eye. Though the widowed Aurora haughtily staves off suitors of her own, she finally discovers her own wild side in an unlikely affair with a retired astronaut played by Jack Nicholson. But the real love story in Terms of Endearment is that between mother and daughter: though they fight incessantly, these two can’t get enough of one another, even when circumstances force them to live thousands of miles apart. Until their lives turn a tragic corner, they don’t fully realize the truth: that theirs is a love that can endure anything . . . just about.

Terms of Endearment marked Brooks’ debut as a film director, after years of writing for movies and TV. And what a debut it was! The hugely popular film was nominated for 11 Oscars, and won 5, including 3 for Brooks (Best Picture, Best Director, Best Adapted Screenplay), and acting honors for MacLaine and Nicholson. (Winger was nominated too.) Though this was a year of power-house ensemble performances in such films as The Big Chill and The Right Stuff, no one seemed to second-guess the Academy on its choices. Terms of Endearment packs a wallop partly because all its characters, however badly they behave at times, are ultimately redeemable, proving themselves worthy of our love.

April 28, 2022

A Glimpse at Some of Our Grand Illusions

With everyone’s mind on the war in Ukraine right now, it seemed an appropriate time to look at one of the great anti-war classics, Jean Renoir’s La Grande Illusion. This 1937 release is better known in America by its English-language title, Grand Illusion. Renoir, the son of the famous French Impressionist painter, himself fought for France during the first World War. (His “everyman” lead actor, Jean Gabin, in fact wears Renoir’s own military uniform on-screen.) Grand Illusion has been declared a masterpiece by such noted American cinéastes as Martin Scorsese and Orson Welles. We’re lucky today that a nitrate-negative movie that once seemed to exist only in smudged prints has—thanks to a complex set of circumstances involving a Russian film archive—been rescued, lovingly restored, and re-released.

This story of a German POW camp and its French inmates is not simply saying, as so many films do, that war is hell. Grand Illusion also explores the role of social class in determining a response to armed conflict. The prison camp is run by the always formidable Erich von Stroheim, playing Major von Rauffenstein, a German aristocrat with splendid manners and a taste for the finer things. Melancholy about the war wounds that keep him from playing a more active role in the fighting, he invites downed French air corps officers to join him for lunch. That’s how he comes to know a fellow aristocrat, Pierre Fresnay’s Captain de Boëldieu, and the two turn out to have much in common, despite their different national origins. Aside from mutual acquaintances and fond memories of dinners at Maxim’s, both feel an obligation to a life of chivalry and patriotism, expressed through daring deeds. As Boëldieu will later put it—just before he makes a climactic gesture--"For a commoner, dying in a war is a tragedy. But for you and me, it's a good way out.”

Though these two aristocrats have a natural rapport, the common French soldiers in the camp feel no affection for wartime chivalry and derring-do. Their first and only goal is to escape, and they work at it throughout the film, digging secret tunnels and otherwise trying to elude their captors, wherever they happen to be held. Though they sometimes engage in jolly horseplay, like a drag show where they’re outfitted as Parisian can-can girls, the lure of freedom is something they can’t forget. It is only when they find themselves in a grim and seemingly impregnable fortress that Gabin’s Lieutenant Maréchal and the nouveau-rich Jewish buddy (Marcel Dalio) with whom he tentatively bonds find a way to escape their surroundings. I won’t go into the role Captain de Boëldieu plays in their desperate scheme, but it leads directly into the most powerful section of the film. Eventually this gives way to a sweet idyll in the German countryside, complete with a kindly German war widow and a cow, before the film comes to a satisfying close.

In 1937, with the forces leading to World War II ramping up, Nazi propaganda minister Joseph Goebbels demanded that prints of Grand Illusion be impounded and destroyed. In 1940 the French government also banned the film, afraid that its even-handed look at German fighting forces would tamp down anti-German fervor during wartime. Today, it’s hard to view any armed conflict as heroic; the “grand illusion” that war is patriotic, and that it brings out the noble side of human nature, seems belied at every turn. Which is all the more reason why Renoir’s masterwork should not be easily forgotten.

April 26, 2022

There Simply Will Be Blood: The Coens’ “Blood Simple”

Last night I partied hearty with two of filmdom’s most talented bros: Joel and Ethan Coen. Fran McDormand was there too, along with a gaggle of Coen pals, on the main street of the quaint semi-rural village where they make their home. My goal was to conduct an interview about filmmaking, but my questions were swept away as we ate, drank, and caroused, culminating in a exuberant hora.

Then I woke up. (Well, it was fun while it lasted.)

The cause of this dream, I am sure, was my late-night viewing of the Coens’ very first feature, Blood Simple. This twisty neo-noir from 1984 marked a number of other firsts for the brothers. It was shot by Barry Sonnenfeld, then a recent film-school graduate but now an acclaimed director of such films as Get Shorty. The score was the Coens’ first of many collaborations with the talented Carter Burwell. It was the first film editor credit for Roderick Jaynes, the Dickensian film editor who is the pseudonym for the busy Coens when they’re in editing mode. It was the first-ever professional screen credit for McDormand, who has been married to Joel Coen since the year the film was made.

The Coens are known for bloody tales laced with black humor. And they love to explore out-of-the-way geographical locales where violence is always on the brink of erupting. That’s what brought them to suburban Texas for a story about a crass bar owner (Dan Hedaya) his restless wife (McDormand), a no-better-than-he-should-be employee (John Getz), and a private detective who’s up to no good (played by the always memorable M. Emmet Walsh). As is often true in the Coen universe, none of them is exactly made of heroic material. But their various forms of greed and lust intertwine in ways that are sometimes gruesome, sometimes darkly funny, as when a corpse doesn’t seem to want to stay dead.

The video release of Blood Simple I watched had an extra treat for film buffs: a featurette in which Sonnenfeld and the two Coens look back at this early work and explain in detail what they could and should have done differently. Blood Simple was made on the slimmest of budgets, after the brothers created an enticing trailer as a way to drum up funding, and some of their economizing proves amusing to discuss. In an early dialogue scene, Getz and McDormand are seen seated in a moving car as the rain pours down. As we learn, the “rain” is actually a crew member on the roof, manning a water-squirting contraption, and the car in question is three highly different vehicles, each of which has certain qualities (like seats close together) that the scene requires. Much later, there’s a violent clash between McDormand and her screen husband on a suburban lawn. In the featurette, Joel and Ethan explicitly point out which parts of the cobbled-together scene were shot on the Texas location, and which parts were pickup shots staged in various east coast locales.

That’s the nature of filmmaking on a low budget, but the brothers are also frank about the ways in which their newness to the filming process ended up working against the aesthetic results. They complain now about their early fondness for lurid lighting effects (like “congo blue” filters) and about their apparent inability to keep some of the actors in focus. They point out with chagrin that the light source on their characters’ faces keeps changing directions, and admit to other lazy choices. They can afford to be honest, because they’re now among the most honored filmmakers of their generation.

April 22, 2022

The Marvelous Mrs. Maisel: No One Loves a Critic!

I’m overjoyed to see The Marvelous Mrs. Maisel back on the tube. Though the first segment of the show’s final season was frequently gibberish, with too many plot strands being introduced far too quickly, the weeks since then have returned to what’s best about Mrs. Maisel: that lovably wacky family unit full of well-heeled misfits and hangers-on who cling together, no matter what. The episode I watched this past week is the best yet: full of family dinners, outrageous hats, and a bar mitzvah to die for. Actually, dying is somewhat of a theme of this episode, in which the pugnacious Susie’s roommate suddenly passes on, leaving her to deliver an obscene but heartfelt eulogy in front of the few folks who’ve bothered to show up to pay tribute. And also in front of those others—from the well-attended funeral next door –who get roped into listening to her memories of a man they didn’t know, and probably wouldn’t have liked.

But my heart really went out in this episode to the redoubtable Abe Weissman (played with panache, as always, by Tony Shalhoub), the paterfamilias of this group. Once a respected, if quirky, mathematician with a secure position at Columbia University, he has made a dramatic gesture by casting aside his dignified titles and taking a low-rent job as the drama critic at The Village Voice. Now, enamored of his new role as a spokesperson for the arts, he has bought himself a twirl-worthy black cape so as to make a suitable splash when attending opening nights.

But disaster awaits. His first theatre gig involves critiquing a new Broadway musical, an updated version of a show that was the annual highlight of the family’s summers at an oh-so-Jewish resort in the Catskills. The entire group snaps up the free tickets that have been lavished upon them, certain that one of their own has now made good on the Great White Way. Uh oh! We don’t see the show itself, but it’s clear from the forced cheerfulness of everyone in the lobby afterwards that this will not be a palpable hit. Abe tries to weasel out of writing a review that will break the playwright’s heart, but professional integrity requires that he call a spade a spade.

Cut to the following day’s bar mitzvah. Happily, no fun is made of the ancient ceremony itself. But the bar mitzvah boy (with the rabbi’s encouragement) departs from his planned speech to talk pointedly about the essential importance of loyalty. And other congregants loudly chime in, making it clear that Abe’s public diss of a congregant’s labor of love is a profound insult—a disgrace!—to his entire community. Pity the poor critic! He’s paid to be honest, but he’s also expected to be kind. Yet, generally, never the twain shall meet.

I responded so strongly to this episode because, like every published writer who’s been a commentator or a critic, I often find myself in the awkward position of being asked for feedback on the work of a friend. We writers know what it’s like: a pal or (even worse) a family member hands you the magnum opus on which they’re been laboring for years, saying, “Give me your honest opinion. If you don’t, I won’t respect you ever again.” Translation: a bit of constructive nit-picking is OK, but you’d better make it clear that this is a work of genius.

April 19, 2022

A Key to “The Apartment”

It’s a curious fact that The Apartment, Billy Wilder’s Oscar-winning dark comedy from 1960, was inspired by David Lean’s 1945 English weepie, Brief Encounter. When Wilder first saw Brief Encounter, he didn’t focus on the two veddy straitlaced Brits who—though married to suitable spouses—fall passionately in love after a chance meeting in an English train station. There’s a scene in the film where, uncharacteristically, they dare to meet at a friend’s flat for a secret tryst. Wilder found himself fascinated not by the lovers but by the friend. Who was this person willing to absent himself from his own home so that others could fulfill their sexual longings in his bed?

Apparently Wilder realized in 1945 that a film about someone enabling adultery would not pass muster in the Hollywood of the production code era. It took 15 years for him and writing partner I.A.L. Diamond to create a hero whose role in life is to lend out his apartment for the sexual escapades of others. Casting Jack Lemmon (a Wilder favorite following his breakthrough role in Some Like It Hot) as a lovable shnook, the writers created a sharp commentary on Manhattan business culture, while also providing an up-to-date romance involving Lemmon’s C.C. “Bud” Baxter and a young woman (Shirley MacLaine’s Fran Kubelik) who is no stranger to sexual exploitation.

This is a film that is all about power relationships. Though in some respects it is dated (Bud’s nifty one-bedroom flat, in the Upper Sixties just off Central Park West, rents for a mere $85 a month), his relationship to the higher-ups who borrow his place for a quickie with a willing secretary seems all too current. Bud puts up with the indignity of being left out in the cold while his bosses canoodle because he sees in their gratitude a chance to move up the corporate ladder at the soulless insurance company where he’s employed. In a place where most of the low-level employees remain near-anonymous, the much-coveted key to Bud’s apartment gives him status, and the hope of promotion. For a while it works, until love enters the picture—in the form of a perky “elevator girl” whose dream is to marry the über-boss (a slick Fred MacMurray, in Double Indemnity mode), a heel who promises he’ll leave his wife and kids for her.

Though The Apartmentis often hilariously funny, with the Wilder/Diamond wit on fine display, this is a film that doesn’t shy away from dark moments--like a near suicide—and from a generally downbeat look at American corporate culture. Watching it recently, I realized how closely it connects with the skewed morality of TV’s Mad Men (2007-2015), in which upwardly mobile advertising execs try to claw their way to the top of the heap. That series is even set in pretty much the same era as the one in which The Apartment was made, when corporate types were developing their own lingo, vocabulary-wise, as well as their own lifestyle, morality-wise. A big difference, though. Whereas Lemmon’s C. C. Baxter is the guy on the outside, looking in, Mad Men’s Don Draper (Jon Hamm) is in the thick of things, finessing his way through the ad world with only the occasional moral qualm. Then there’s Peggy Olson, as played by Elisabeth Moss. She starts out as eager and innocent as Fran Kubelik, but it doesn’t stick. Her smarts and her ambition make her want to beat the boys at their own game. By the end, she’s as soulless as the rest, but the key to the executive washroom is in her grasp.

April 14, 2022

A Tender Look Back at “Tender Mercies”

Robert Duvall has long been one of Hollywood’s most respected character actors, starting with supporting roles in such major films as To Kill a Mockingbird (as Boo Radley, 1963), MASH (as Major Frank Burns, 1970) and The Godfather films (as “fixer” Tom Hagen, 1972 and 1974). Unlike most character actors, he ultimately made the leap into leading roles. Having grown up in a military household, he brought aa fierce authenticity to the complex role of Bull Meechum in The Great Santini. In 1981, the part earned him his first nomination as Best Actor, but he was up against such landmark performances as that of Robert De Niro in Raging Bull (the eventual winner) and John Hurt in The Elephant Man. Three years later, though, he took home the Oscar for the role of country singer Mac Sledge in Tender Mercies.

Also winning an Oscar for Tender Mercies was its writer, Horton Foote, the Texas playwright who adapted To a Kill a Mockingbird for the screen, and wrote both the stage and film versions of The Trip to Bountiful. Foote was a Texas country boy to the tips of his fingernails (though he died in Connecticut), and he could be relied upon to convey simply and directly a down-to-earth life. That’s why he was honored by the Academy for a screenplay some might call slight. (Leonard Maltin’s now defunct but invaluable guide calls it “not so much a story as a series of vignettes.”) In this particular Foote project, apparently written with Duvall in mind, the central character is a noted country-western singer, now on the skids, who finds resurrection in the home of a young widow running a motel and filling station in the middle of nowhere.

Country western is not my music of choice, but my colleague Diane Diekman has made a career out of exploring the lives of country music stars like Marty Robbins and (upcoming) Randy Travis. I’ve read her Live Fast, Love Hard: The Faron Young Story, about a singer whose considerable talent was eclipsed by his outrageous lifestyle, and I think I have some sense of what stardom can do to dirt-poor country boys. The norm for Young and others, when at the height of their powers, seems to have been fast cars, hot women, and cold brews, with a firearm or two thrown in for good measure. Duvall’s Mac Sledge is first seen as a down-and-out drunk. But his gentle connection with Vietnam widow Rosa Lee and her scrappy young son brings out the best in him. Through them he learns to live again, to forget the bitter marriage he’s fleeing, and to find comfort in family and faith.

That last is key: Robert Altman had it right in Nashville (1975), in which the film’s many interpersonal struggles are forgotten on Sunday morning when everyone turns out to praise the Lord. In Tender Mercies (the title comes from a bedtime prayer that Rosa Lee fervently recites), old-time religion becomes a counterweight to the heavy burdens Sledge sees himself carrying. By the film’s end, despite it all, he’s returning to the music he loves. And, even more important, he’s finally able to see himself as a happy man. Yes, he still mistrusts the notion of happiness, all too aware that bad things can happen to good people. Still, he’s now finally able to accept the positive taspects life and move on.

This isn’t a great film, but it’s anchored by a great performance. However plodding and predictable the action might be, Duvall keeps us connected with life as it is lived.

At a time of many religious holidays (Passover, Eastern, Ramadan), I wish all my readers well. Special thanks to Diane Diekman for helping me see the glories of country music. Write to her at djean@midco.net if you’d like to be added to the mailing list for her comprehensive country music newsletter.

April 12, 2022

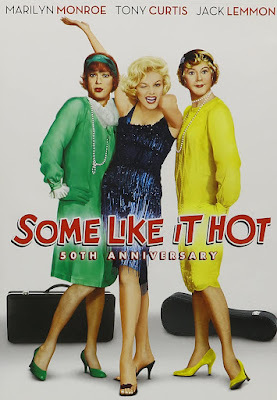

Clothes Make the Man?: “Some Like It Hot,” “Tootsie,” and “Mrs. Doubtfire”

It’s as old as Shakespeare: a man dressing up in women’s clothing. Of course in Shakespeare’s day there was an added complication. Because rules of public morality determined that it would be indecent to have a woman in a theatre troupe, young men put on dresses and wigs to play all the female roles. This helps explain why in so many Shakespearean comedies (like Twelfth Night and As You Like It) female characters spend much of their time in male disguise. The resulting gender confusion was explored by Tom Stoppard and company in one of my favorite romantic films, Shakespeare in Love. In that 1998 Best Picture winner, the theatre-mad Viola de Lesseps (Gwyneth Paltrow) disguises herself as a male—complete with a tiny mustache—so she can audition to join Shakespeare’s acting company. She ultimately originates the role of Juliet while having a doomed affair with the playwright himself.

Usually, on stage and in movies, it’s men dressing up as women. Even long after actresses were accepted on stage, the British have continued to love the buffoonish spectacle of a well-padded man tricked out in a woman’s petticoat and bonnet. The so-called “dame show” has been a holiday staple for hundreds of years. Clearly it was this tradition that inspired Ray Bolger’s starring role in the hit musical version of a popular stage farce, Charley’s Aunt, in which a young man tries to further his romantic goals by disguising himself as a visiting dowager. The British original, which debuted back in 1892, was ultimately filmed at least 13 times, in productions all over the world. No one, it seems, could get enough of a guy sporting a flouncy skirt.

In 1959, Billy Wilder and I.A.L.Diamond updated the “dame show” tradition by combining it with a gangster thriller in Some Like It Hot. In this beloved comedy, two musicians played by Tony Curtis and Jack Lemmon accidentally witness the St. Valentine’s Day Massacre. Desperate to escape detection, they disguise themselves as women and join an all-girl band en route from Chicago to Miami Beach. Their masquerade involves the usual men-dressed-as-women tropes, as they wobble in high heels and struggle to project coy feminine charm. But the two authors add their own hilarious touches, as Curtis takes on a second identity (that of a grieving millionaire who’s lost his sex drive) in order to woo band singer Marilyn Monroe, while Lemmon somehow finds himself engaged to marry dingbat tycoon Joe E. Brown.

Twenty-three years later, Larry Gelbart and some others put a new theatrical spin on the man-in-woman’s-clothing comedy. The film was Tootsie: its central character, Michael Dorsey—played by Dustin Hoffman—is a talented but pugnacious stage actor who’s burned so many bridges that he can only land an acting job by trying on a new gender. As Dorothy Michaels, he lands a gig on a soap opera, quickly becoming a fan favorite. Tootsie is full of subtle commentary on how women are treated, as Michael’s attitudes evolve while his fanbase grows.

Then (sigh) there’s 1993’s Mrs. Doubfire, in which Robin Williams, faced with losing his children to divorce, gets the bright idea of turning himself into a cozy British nanny in order to be near them. Completely fooling his ex-wife and everyone else, he manages to prove that he’s indispensable to the happy running of their household. I tried watching this on a recent plane flight, and found the playing out of this family story grotesque in its reliance on crude gender stereotypes. A dad as Mr. Mom showing off a D-cup? Yuck.

Then (sigh) there’s 1993’s Mrs. Doubfire, in which Robin Williams, faced with losing his children to divorce, gets the bright idea of turning himself into a cozy British nanny in order to be near them. Completely fooling his ex-wife and everyone else, he manages to prove that he’s indispensable to the happy running of their household. I tried watching this on a recent plane flight, and found the playing out of this family story grotesque in its reliance on crude gender stereotypes. A dad as Mr. Mom showing off a D-cup? Yuck.

April 7, 2022

“A Foreign Affair”: Billy Wilder 's Bittersweet Take on Post-War Germany

My Billy Wilder journey continues, as I work my way through Joe McBride's comprehensive Billy Wilder: Dancing on the Edge. This week I saw one of Wilder’s more unheralded triumphs, the 1948 A Foreign Affair. This dark romantic comedy stands out partly because of where it was filmed: in the rubble of Berlin, following the end of World War II. (At the close of his wartime service in the U.S. Army, Wilder was promised government assistance if he shot a movie in occupied Deutschland, thus giving a boost to the ruined German economy as well as to the revival of the German film industry.) A Foreign Affairdeals, sometimes sardonically, with the Allies’ efforts to rebuild the devastated German capital. But its primary subject is, as always with Wilder, the vagaries of the human heart. Though Nazis, and their collaborators, are hardly looked on with favor in the course of the film, the occupying American army does not escape unscathed. And a visiting American congressional delegation on a fact-finding tour is treated with all the satirical thrust that Wilder can muster.

Jean Arthur came out of retirement to play Phoebe Frost, a strait-laced Iowa congresswoman bent on improving the morale of the occupying U.S. troops. When she strays from the official tour, she’s alarmed to find that young American servicemen, mistaking her for a blonde fraulein, are eager to canoodle. She’s also appalled when she observes that locals (especially attractive young women) are more than happy to bestow their favors on Americans who can provide them with chocolate bars and nylon stockings. Pretending to be a giggly German maedchen, she goes along with two G.I. Joes to a seedy local club. That’s where she frowns with disapproval on a nightclub singer, Erika von Schlütow, played by Marlene Dietrich with her usual potent mix of glamour and irony.

Though Dietrich herself was known for her unrelenting opposition to Hitler and his thugs, her character in this film represents the German citizens who will do whatever it takes to get by. That’s why, although she’s embroiled in a powerful (and possibly sado-masochistic) relationship with an American officer, John Lund’s Captain Pringle, there’s also a Nazi higher-up lurking in her past. The film’s most striking moments involve her encounters with Congresswoman Frost, who in an ironic turnabout must look to Erika to save her from public humiliation, not to mention legal jeopardy. Connecting the two women is Captain Pringle, who is not above taking on romance as part of his military duties.

Looking back on Wilder’s life, as McBride does so effectively, it’s rather startling to see him focusing on the post-war neediness of the German populace. Wilder, a Jewish man who grew up in Vienna and began his filmmaking career in Berlin, was never able to save his own mother and other relatives from the Nazi death camps. Needless to say, he had no great love for the German hierarchy that led the country into war. And his life in the United States, from 1933 onward, paved the way for fame and fortune in his adopted land. Still, unlike Congresswoman Phoebe Frost, he cannot view the German people as undeserving of sympathy. Scrounging for food and small luxury items (as well as the occasional moment of fun) in their bombed-out city, they awaken his compassion. And it’s in keeping with his mordant temperament that he resists simple delineations of right and wrong. So A Foreign Affair offers up not (as per its poster) hilarious comedy, but rather food for thought, which is far more nourishing than a chocolate bar.

Joe McBride, the man himself, adds to this post with some important info for cinéastes:" Did you know I did the audio commentary on the recent Kino Lorber Blu-ray edition?For a long time the film was MIA in home video." He adds the all-important Amazon link: https://www.amazon.com/Foreign-Affair-Blu-ray-Jean-Arthur/dp/B07SNNNMQ7

April 5, 2022

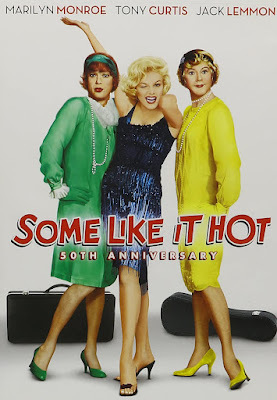

Now You See Him: The Many Faces of Roger Corman

Not long ago, I found myself watching Ron Howard’s spectacular Apollo 13 on a big-screen TV. As the tense drama unfolded, I spotted several members of the Howard family. These included brother Clint as a quirky engineer in the NASA control room and father Rance as a minister on hand to comfort Jim Lovell’s kinfolk during the patriarch’s perilous return to earth. After a round of tough auditions, Howard gave in to his father’s lobbying efforts and cast his own mother, Jean, in the small but showy role of Lovell’s grandmother, who has absolute faith that “if they could get a washing machine to fly, my Jimmy could land it.” I wasn’t surprised to see all these Howards: though Ron is no pushover when it comes to casting, he enjoys working with members of his family. But I was momentarily surprised at an early scene where, among a congressional delegation touring a NASA facility, I spotted my former boss. Yes, Roger Corman.

Roger ‘s role, that of a congressman grilling NASA reps about cost containment, is a knowing nod to the Corman reputation as a penny-pincher. The part gave Howard an opportunity to salute the man who’d made him a film director. There’s a long tradition of Corman alumni giving cameo roles to their former boss. It’s a tradition that had previously been sidestepped by Howard, who didn’t think much of Roger’s acting chops. But fellow director Jonathan Demme—who’d used Roger in both The Silence of the Lambs (as the head of the FBI) and Philadelphia (as a crafty businessman) convinced him that Roger’s dramatic skills had vastly improved. Hence his tiny but effective role in what may be Howard’s very best film.

The first Cormanite to hire his former boss as an actor was Francis Ford Coppola, who cast him in The Godfather Part II as a U.S. Senator on a high-profile panel investigating organized crime.. Coppola had observed that politicians, when in front of news cameras, came off as intelligent and dignified, but also slightly self-conscious. This description fit Roger perfectly.

Director Joe Dante has joked to me that part of the pleasure of using Corman in a cameo role is paying him the minimum wage allowable by the Screen Actors Guild: “Everybody wanted Roger to work for them for nothing, because we all worked for him for nothing.” When Dante made his own first post-Corman film, the highly successful The Howling ,he asked his old mentor to do a walk-on in a barroom scene. It was Corman’s idea, enthusiastically adopted by Dante, that he spoof his cheapskate image on camera by checking a pay telephone’s coin-return slot for loose change. Most Corman cameos, however, take advantage of his naturally authoritative presence, as Demme did when making him the FBI chief, with his photo beaming down from office walls.

In 2011, though, a very different Roger appeared in a spoofy TV movie. Here’s how I once described his scene in Sharktopus: “Fade in on a pristine stretch of tropical shore, where we spot an old codger with his shirt unbuttoned halfway down his chest. Sauntering along, he ogles a bikini-clad lovely who has just bent down to dig up a rare coin. When a tentacled sea-beast unexpectedly looms, dragging the shrieking beauty into the surf, he reacts with mild surprise. Then, shrugging off the carnage, he makes a beeline for the coin she’s dropped in the sand. The scene ends on his self-satisfied grin.” Roger had fun playing that greedy beach bum. And on his 96th birthday I wish him lots more fun in the years ahead.

Beverly in Movieland

- Beverly Gray's profile

- 10 followers