Beverly Gray's Blog: Beverly in Movieland, page 34

July 19, 2022

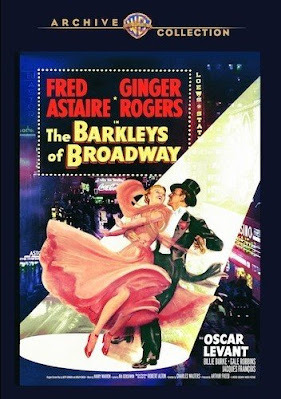

The Barkleys of Broadway: It Takes Two to Tango -- or Tap Dance

I once had the bizarre experience of seeing an old Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers musical in the middle of the night while on a flight to Europe. While the other passengers slumbered in their seats, I watched 1939’s The Story of Vernon and Irene Castle. This sentimental confection about a real-life ballroom dance team from the early 20th century is moderately entertaining, but it climaxes with a moment that certainly gave me pause. (It’s one that that the airline folks clearly overlooked when choosing programming for their seatback entertainment systems.) Near the end of the film, with World War I raging, Irene Castle gets a message regarding her beloved husband, who has enlisted in the British flying corps. It’s bad news, both for her and for airline passengers who like old musicals: Vernon Castle has just died in a plane crash.

No such real-world shock mars Astaire and Rogers’ very last film, 1949’s The Barkleys of Broadway. Still, it does reflect, just a bit, on the history of the Astaire-Rogers teaming. They had shot 9 musicals together at RKO, starting with 1933’s Flying Down to Rio, in which both were featured players. Then, as Astaire looked for other partners as well as solo opportunities, Rogers segued into non-musical roles. Some were comedies, but her dramatic portrayal of a young career gal tempted by money and love won her an Oscar for 1940’s Kitty Foyle, subtitled The Natural History of a Woman. I’m especially fond of her hilarious role as a grown woman masquerading as a precocious kid in the first American film directed by Billy Wilder, 1942’s The Major and the Minor.

So the Astaire-Rogers partnership seemed done for, until it became clear that an emotionally fragile Judy Garland was not up to the role of Astaire’s wife and performance partner in an MGM full-color extravaganza, The Barkleys of Broadway. I’m unclear how much rewriting was done to accommodate the return of Rogers into Astaire’s musical orbit, but the predictably witty Betty Comden/Adolph Green screenplay seems to pick up on the duo’s real-life relationship, including Astaire’s perfectionism as well as Rogers’ turn toward drama. They play a married couple who are at the height of their Broadway success as a song-and-dance team. Mere moments after they’re praising one another to the skies for their latest stage success, they’re once again bickering about his nitpicking ways and her quickness to take offense. When a handsome French director tells Dinah Barkley (Rogers, of course) that she’s a born dramatic actress, and proceeds to star her in a new play about the young Sarah Bernhardt, the marriage seems kaput. Nor does her dramatic debut look particularly promising, since her new director seems unable to coax from her the histrionic dynamism that the play requires. But Astaire’s Josh Barkley, alerted to his wife’s floundering by one of the era’s popular movie sidekicks, acerbic pianist Oscar Levant, finds a clever way to secretly coax from Dinah a stellar performance. Of course the marital partnership is saved, and everyone lives happily ever after.

Although I thrill to the best of the swoony Astaire/Rogers ballroom duets, my particular favorites are the novelty numbers. Fred Astaire seemed to revel in choreographies that placed his dance skills against unlikely backdrops and gave him eccentric props. See, for instance “Drum Crazy” from Easter Parade, and the Royal Wedding number where he dances on the ceiling. In The Barkleys of Broadway he outdoes himself (the number is called “Shoes With Wings On”) by portraying a cobbler nearly overwhelmed by pairs of shoes with minds of their own. Brilliant!

July 15, 2022

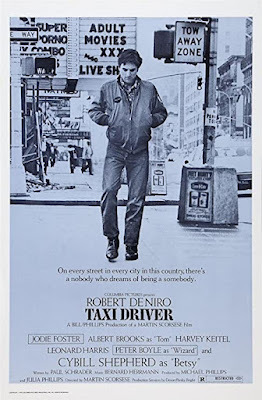

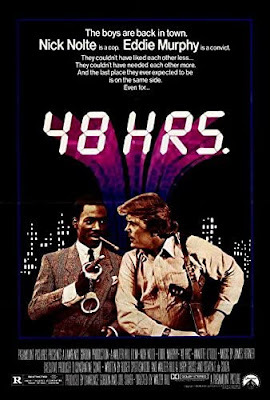

“48 Hrs.” and “Taxi Driver”: The Buddies and the Loner

July appears to be my month for violent movies. Within the past week I’ve watched both 48 Hrs.(1982) and Taxi Driver (1976). I was impressed by them both, but the first strikes me as a guilty pleasure. And the second, alas, seems like a wake-up call.

The success of 48 Hrs. at the box office helped kick off the whole buddy cop genre (see, for instance, the Lethal Weapon franchise). The pairing of big, burly, taciturn Nick Nolte and small, slim, gabby Eddie Murphy (in his very first movie role) also showed how the unlikely pairing of a white man and a Black one in Stanley Kramer's The Defiant Ones could evolve into the kind of spiky but eventually comedic relationship epitomized by action romps featuring Richard Pryor and Gene Wilder. But 48 Hrs. is no comedy. And Murphy’s character, Reggie, is not actually a cop. Instead, he’s a convict, a career thief released from prison for (yes!) 48 hours in order to help track down a vicious former associate who’s done him dirt.

It's an unlikely premise, but one that plays exceedingly well, as Reggie butts up against Nolte’s my-way-or-the-highway Jack. Wearing a spiffy Armani suit and (after three celibate years in prison) endlessly on the hunt for willing females, Reggie eventually reveals that he’s deft enough and brave enough to help face down a killer. In this he wins the respect of Jack, a rumpled mass of a man who’s got his own female troubles and not much support from his superiors. Respect between Reggie and Jack grows slowly, though the early interactions between the two are laced with nasty jibes and racial epithets that are hard to enjoy. We know, of course, that all will be right in the end, though they still enjoy jerking one another’s chain up until the final fadeout. (Yes, the relationship survives in a 1990 sequel.)

Director Walter Hill is best known for action, and the film’s opening – a bold escape from a penal work camp, accompanied by James Horner’s thrilling music -- may be its most viscerally effective part. It’s rivaled by the lethal wrap-up in a misty San Francisco Chinatown haunt. But the centerpiece, of course is two mismatched men who find themselves becoming pals.

Which brings me to Taxi Driver, Martin Scorsese’s deeply disturbing look at a military veteran adrift in the urban jungles of New York City. Unable to sleep, Robert De Niro’s Travis Bickle takes a job as an all-night cab driver, cruising through Manhattan’s meanest, dirtiest, most crime-ridden streets. His is a solitary life. When a social relationship with a pretty blonde working on a political campaign (Cybill Shepherd) fizzles, he becomes obsessed with rescuing a child prostitute (Jodie Foster) from her sordid line of work. It’s easy enough for him to assemble an arsenal of weapons, and to transform himself into a muscle-bound mohawk-wearing killing machine with hair-trigger reflexes and a grudge against pretty much everyone. By the end of the film he is a lethal weapon, though a bizarre twist turns him into someone’s idea of a public hero.

Bickle’s soul-crushing loneliness, combined with obvious PTSD from his Marine Corps days, makes him all too ripe to see himself as a potential toxic avenger. The ready availability of military-style fire power is what inspires him to take into his own hands the idea of cleaning up the world. Sadly, there are too many others out there today whose minds work in the same deadly fashion. If only our nation weren’t so ready to sell them the tools to fuel their obsessions.

July 12, 2022

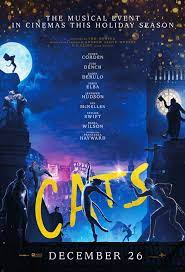

Letting the Cat Out of the Bag About “Cats”

Damn you, Andrew Lloyd Webber! Yes, you’ve enlivened the world with major stage extravaganzas like Evita and Jesus Christ Superstar. Your greatest hit, The Phantom of the Opera, may have seemed overwrought to me, but it had the virtue of introducing thousands of fans to the joys of musical theatre. For better or for worse, you certainly know how to write a tune that won’t leave my head.

On a recent plane flight, I decided it was time to check out the film version of one of your best-known works, a show about which I’ve had decidedly mixed emotions. I first saw Catsin 1985, when it touched down in L.A. as part of its first national tour. (So great was the public enthusiasm for this elaborate show—one emphasizing music, dance, and over-the-top scenic effects—that it ran for 21 years in London and 18 on Broadway.) In 1985 while writing on theatre for the Los Angeles Times, I had the fun of taking a backstage look at the show’s elaborate makeup designs. That’s why I was granted two house-seats, which allowed me to introduce a very young relative to the magic of live theatre. Out of this came a passion for the musical stage that has never left him.

So Cats, the stage musical, will always have a warm spot in my heart. I’ve never thought of it as a play, exactly. It’s more like the masques embraced by the royals of Shakespeare’s day: a theatrical confcction that delights the senses through its appeal to eye and ear. But this stage adaptation of playful poems by none other than T.S. Eliot is not much on basics like characterization and plot. Here’s the IMDB summation of the dramatic throughline: “A tribe of cats called the Jellicles must decide yearly which one will ascend to the Heaviside Layer and come back to a new Jellicle life.” Meaningful, no?

I had thought that with its cartoony characterizations, its plotlessness, and its heavy reliance on whimsy, Cats would be immune to Hollywood’s meddling. And so it was, until 2019, when Tom Hooper (known for The King’s Speech and Les Misêrables) got his hands on it. Hiring a big-name cast, he set about transferring the magic of the stage experience to the big screen. Critical response was not pretty. Cats racked up a series of Worst Film of the Year awards, including the infamous Razzie, and audiences stayed away in droves. No one, it seems, wanted to watch actors with pointy ears, tails, and garish makeup, cavorting in close-up. It was, in short, a catastrophe.

Still, I persisted in being curious about this debacle. Some of the actors in the featured comic numbers, like James Corden as the snooty Bustopher Jones and Rebel Wilson as domestic queen Jennyanydots, are as embarrassing as I had heard. Jennifer Hudson warbles “Memory” beautifully, but her pillowy lips spoil any possible illusion that she’s a cat. Idris Elba’s evil-minded Macavity makes no more sense that it did on stage. But somehow Judi Dench retains her dignity as Old Deuteronomy. To me the film’s vocal star was (surprise!) Taylor Swift, who looks a lot like a slinky feline as she belts out the jazzy “Macavity” late in the film.

And when things are turned over to the dancers, in choreography by Andy Blankenbuehler of Hamilton fame, some glimmers of magic appear. The film’s one innovation is the addition of an adorable white kitten, Victoria, who listens in wonder to all the goings-on. Ballerina Francesca Hayward is absolutely purr-fect in the role.

July 8, 2022

C'mon Down with “C'mon C'mon”

C’mon C’mon is a movie that has to grow on you, like an ornery kid with whom you’ve suddenly been saddled. He ricochets around, talking a blue streak, and mostly you wish for a modicum of peace and quiet. But all at once, just before you reach the end of your tether, you realize that life with him in it has gotten a great deal more interesting. That he is, in fact, irreplaceable.

What I’m describing, of course, is the central situation in Mike Mills’ small movie, which debuted last summer at the Telluride Film Festival, to much critical acclaim. It’s too modest in its ambitions to be an Oscar sort of movie, but it was up for various independent film awards. I saw it on an airplane, not the ideal place to follow a flick that bounces around in time. Still, its small scale and basic simplicity made my trip through the skies pass nicely, and its ultimately upbeat message helped make those skies seem more friendly than usual.

Writer-director Mills, who’s married to fellow indie phenom Miranda July, has attracted attention with some bigger films. In 2012, Christopher Plummer won his Oscar for portraying a character in Mills’ Beginners who was in fact a version of Mills’ own dad. (It’s one of those amazing stories: Six months after Mills’ mother died of brain cancer, his father came out as gay at age 75. After 45 years of marriage, he was suddenly ready to try his newly revealed orientation on for size, creating much consternation among his offspring.) In 2016, Mills wrote and directed 20th Century Women, which gave Annette Bening a much-heralded role, along with an Oscar nomination for Mills’ screenplay.

Clearly, prominent actors like to be challenged by Mills’ character-driven material. His star in C’mon C’mon is Joaquin Phoenix, in his first feature since winning an Academy Award for the macabre title role in Joker. Phoenix’s Johnny in C’mon C’mon is far more of an everyday guy than was Batman’s nemesis, but Johnny too has his share of oversized problems. Johnny, living in NYC, is pretty much alone in the world. There’s a soured romance in his past, and he and his West Coast-based sister, Viv (Gaby Hoffman) haven’t spoken since they quarreled over the handling of their Alzheimer’s-ridden mother. (I, in my economy-class seat, had a hard time figuring how the mother’s death fit into the story’s basic chronology.) But now, with Viv’s husband having suffered a mental breakdown that requires hospitalization, she is desperate to find a place to stow her precocious but clearly troubled son, Jesse, while she tries to salvage what’s left of her marriage.

Johnny works as a radio journalist, traveling the country to record interviews in which children talk about their hopes and fears. So he’s used to being around kids. But that’s a far different thing from hanging out with Jesse on a daily basis in his tiny New York walk-up. Jesse likes to butt up against the adult world, testing his limits, but he’s also grappling with his own fears of following in his father’s footsteps. It’s only when they end up in New Orleans together, as part of Johnny’s work, that man and boy finally coalesce and form a genuine bond.

The role of nine-year-old Jesse is crucial to the success of this film. He’s played with impressive authenticity by young Woody Norman. I was stunned to learn that this very L.A. kid was played by a boy born and bred in North London. There was a time when Brits couldn’t convincingly do American accents. Clearly, no more.

C’mon C’mon is a movie that has to grow on you, like an ornery kid with whom you’ve suddenly been saddled. He ricochets around, talking a blue streak, and mostly you wish for a modicum of peace and quiet. But all at once, just before you reach the end of your tether, you realize that life with him in it has gotten a great deal more interesting. That he is, in fact, irreplaceable.

What I’m describing, of course, is the central situation in Mike Mills’ small movie, which debuted last summer at the Telluride Film Festival, to much critical acclaim. It’s too modest in its ambitions to be an Oscar sort of movie, but it was up for various independent film awards. I saw it on an airplane, not the ideal place to follow a flick that bounces around in time. Still, its small scale and basic simplicity made my trip through the skies pass nicely, and its ultimately upbeat message helped make those skies seem more friendly than usual.

Writer-director Mills, who’s married to fellow indie phenom Miranda July, has attracted attention with some bigger films. In 2012, Christopher Plummer won his Oscar for portraying a character in Mills’ Beginners who was in fact a version of Mills’ own dad. (It’s one of those amazing stories: Six months after Mills’ mother died of brain cancer, his father came out as gay at age 75. After 45 years of marriage, he was suddenly ready to try his newly revealed orientation on for size, creating much consternation among his offspring.) In 2016, Mills wrote and directed 20th Century Women, which gave Annette Bening a much-heralded role, along with an Oscar nomination for Mills’ screenplay.

Clearly, prominent actors like to be challenged by Mills’ character-driven material. His star in C’mon C’mon is Joaquin Phoenix, in his first feature since winning an Academy Award for the macabre title role in Joker. Phoenix’s Johnny in C’mon C’mon is far more of an everyday guy than was Batman’s nemesis, but Johnny too has his share of oversized problems. Johnny, living in NYC, is pretty much alone in the world. There’s a soured romance in his past, and he and his West Coast-based sister, Viv (Gaby Hoffman) haven’t spoken since they quarreled over the handling of their Alzheimer’s-ridden mother. (I, in my economy-class seat, had a hard time figuring how the mother’s death fit into the story’s basic chronology.) But now, with Viv’s husband having suffered a mental breakdown that requires hospitalization, she is desperate to find a place to stow her precocious but clearly troubled son, Jesse, while she tries to salvage what’s left of her marriage.

Johnny works as a radio journalist, traveling the country to record interviews in which children talk about their hopes and fears. So he’s used to being around kids. But that’s a far different thing from hanging out with Jesse on a daily basis in his tiny New York walk-up. Jesse likes to butt up against the adult world, testing his limits, but he’s also grappling with his own fears of following in his father’s footsteps. It’s only when they end up in New Orleans together, as part of Johnny’s work, that man and boy finally coalesce and form a genuine bond.

The role of nine-year-old Jesse is crucial to the success of this film. He’s played with impressive authenticity by young Woody Norman. I was stunned to learn that this very L.A. kid was played by a boy born and bred in North London. There was a time when Brits couldn’t convincingly do American accents. Clearly, no more.

July 5, 2022

Ready? Get Set!

I’m told the latest indignity of travel is that instead of the handy personal seatback TV screen that makes long flights tolerable, you are now encouraged to hook up the airline’s communications system to your very own personal device, like an awkward iPad or an itty-bitty mobile phone. Aargh! Fortunately for me, on my last business trip to NYC I had a genuine (and mostly working) seatback screen to amuse me. Of course, the movie offerings were spotty, which is why I found myself choosing to see a most unlikely documentary, one that had never before come to my attention. It’s called Set!, and I was hooked by the explanatory subtitle: “An Inside Look at the World of Competitive Table Setting.”

Yes, really. It’s called “Table-Scaping,” by those in the know. The idea is to set a table that observes all formal rules of correctness (utensils, plates, and napkins all in exactly the right position), while also displaying creativity through the use of backdrops, table coverings, and elaborate decorative tchotchkes. Each competition selects a theme, of course, and hands out medals and trophies to those who fulfill it best. Set! focuses on one such competition, a major annual event staged on the grounds of the Orange County Fair in Costa Mesa, California. Vying for the coveted Best of Show honors are a number of middle-class, middle-aged ladies, and at least one amiable man. The documentarians clearly are having fun exploring the various personalities on display: the much-decorated table-scaping veteran; the mother/daughter duo; the world-traveler showing off her souvenirs; the kook with mystical leanings. Mostly they’re a convivial bunch, until push comes to shove. But some of the more affluent (those who set their tables with Waterford crystal goblets) do tend to look down on one poor schnook. He’s out of work and short on cash, which is why his decorative supplies come from the local dollar store. How déclassé!

At the competition being covered in Set!, the theme is International Travel. This lends itself quite naturally to colorful displays of the “It’s a Small World” variety. (The out-of-work guy tries a sweetly childlike Dr. Seuss variation: “Oh, The Places You’ll Go!”) Someone evokes Marrakesh, while one big winner simulates dinner in an Italian vineyard, complete with a grape-festooned gazebo lit by a Venetian chandelier. Two contestants choose African safari settings. One of them bets big on a romantic picnic in the veldt, while the other has something quite different in mind. This particular contestant, something of a maverick, traditionally begins her table-scaping efforts with a good soak in a sensory deprivation chamber to stir up ideas. Maybe that’s why she leans toward the macabre. She surrounds her tableware (all correctly placed, of course) with taxidermized African wildlife, accented with rifles, bullets, and fake blood. Though she wins no big prizes, she certainly gets a lot of attention.

I once was a huge fan of Christopher Guest spoofs, those hilarious mock-docs in which—with a cast full of gifted improvisers—he affectionately satirized people’s passion for folk music (A Mighty Wind) or regional pageants (Waiting for Guffman). Perhaps the most popular of these was Best in Show (2000), an outrageous look at the contestants, both human and canine, in a snooty, highly-competitive dog show. Guest seems, alas, to have left that genre behind, but I’d think table-scaping would inspire him to reach even greater heights. Just imagine what Catherine O’Hara and Eugene Levy could do with some plates, forks, and goblets. That’s a meal I’d gladly eat. Cheers!

July 1, 2022

Making a Killing in “Coogan’s Bluff”

I first saw Coogan’s Bluff more years ago than I’d care to count (OK, it came out in 1968), when I was a fledgling film critic for the UCLA Daily Bruin. Not much of a fan of action films, I was totally lacking in context with which to assess Clint Eastwood’s first of five collaborations with director Don Siegel. Today, familiar with Eastwood’s early spaghetti-western period as well as his later renown for tough-guy roles, I can clearly see how Coogan’s Bluff led directly into Eastwood’s infamous Dirty Harry period.

The movie’s opening scene tells you everything you need to know about Coogan. Driving a jeep purposefully through the bleak but beautiful Arizona desert, he ignores the urgent bulletins coming in through his police radio. A Native American in a loincloth, armed with a rifle, seems to have the drop on him, but Coogan fells him with a kick to the balls, then snarls, “Put on your pants.” The guy turns out to be a wife-killer, so we’re not too sorry for him. But Coogan’s treatment of Running Bear is surprisingly cavalier: he chains him to the post of a local home, then scoots inside and initiates a bathtub romp with the pretty homeowner, whose other half is conveniently out of town.

Deputy Sheriff Walt Coogan always gets his man. But he doesn’t care how many formal procedures he violates in the process. To take him down a peg, his superiors send him to New York City, to bring back a fugitive named Jimmy Ringerman (Don Stroud) who’s being charged with murder. The tight-lipped lawman and the Big Apple turn out not to be a good fit. First he’s stiffed by a cabbie who demands that his tiny satchel be charged as luggage. Then Ringerman is not immediately available for extradition: he’s suffered a bad acid trip and landed in Bellevue, which means a lot of red tape must be navigated before Coogan can fly home. And everyone he meets assumes that, with his Stetson and his pointy boots, he must be from Texas. So he’s hardly an “I ♥ NY” kind of guy.

Still, there are compensations, Strictly in the line of duty, he gets it on first with a sappy social worker (Susan Clark) who is far too protective of her clients to watch out for her own welfare. Then there’s the pretty but ditsy hippie chick (Tisha Sterling) who likes Jimmy Ringerman and psychedelics, not necessarily in that order. The women in this movie, who also include Ringerman’s hard-boiled mother and an ancient hag convinced that every man she’s ever met is out to rape her, are not the brightest representatives of the female of the species.

Coogan loves sex, but he’s equally a fan of beating people to a pulp. Still, he can’t entirely hold his own in a pool hall where he’s jumped by a whole squad of Ringerman’s pals. He makes up for it later up at the Cloisters (yes, there’s some New York location shooting to go along with some highly artificial-looking interiors), where Ringerman is hanging out. They both commandeer motorcycles, and we’re treated to some classic stunt driving before Ringerman is finally felled.

Which doesn’t mean Coogan can sidestep all red tape. The local police lieutenant, played by Lee J. Cobb, sees to that. But the film concludes with what passes for a happy ending, with Coogan and his prisoner heading home, while Susan Clark in a red miniskirt tearfully waves bye-bye.

Kudos to Lalo Schifrin for his jazzy score, and to Hollywood veteran Betty Field as Ringerman’s no-bullshit mom.

June 28, 2022

“Prizzi’s Honor”: Where Are They Now?

After The Godfather (1972) and The Godfather, Part II (1974) swept up every honor in sight, Hollywood couldn’t get enough of Italian-American mafioso types. But well before Martin Scorsese’s Goodfellas (1990, starring the late Ray Liotta) and TV’s The Sopranos (for six seasons, starting in 1999), came Prizzi’s Honor, directed by one of Hollywood’s oldest and feistiest lions. I’m talking about John Huston, responsible over the decades for such studio gems as The Maltese Falcon in 1941, The Treasure of the Sierra Madre in 1948, The African Queen in 1951, and The Man Who Would be King in 1975. As an actor, he also turned in an unforgettable performance as sinister tycoon Noah Cross in 1974’s Chinatown. Prizzi’s Honor was released in 1985, when Huston was almost eighty. It was his last film but one; he followed it up with a poignant adaption of a James Joyce story, The Dead, made as he approached his own death in 1987.

Prizzi’s Honor, too, has its somber moments, but it is at base a comedy, if an extremely macabre one. Jack Nicholson, reuniting with Huston a decade after Chinatown, plays a Mafia hitman with a deep loyalty toward his ancient padrone. The latter, Don Corrado Prinzi, is vividly played by a sepulchral-looking, gravel-voiced William Hickey, who earned an Oscar nomination for this role. The body of the film starts, à la The Godfather, with an elaborate cathedral wedding scene in which an overblown bride is joined in holy wedlock to a shrimpy little groom, as a massive group of wiseguys looks on with approval. Nicholson’s Charley Partanna is one of them, cocky and slightly cynical about the world around him, but newly entranced by the unknown blonde in the balcony.

That luscious lady in lavender is played by Kathleen Turner, just three years after she’d burst onto the screen as the dangerous Matty Walker in Body Heat. Svelte and blessed with an seductively throaty voice, she couldn’t be more enticing. Of course Charley is smitten, but the surprise is that she seems to be enraptured by him as well. Their coupling plays out both in New York and L.A. (lots of amusing shots of a now-defunct airline heading right to left, then left to right, across the screen). But who is this mysterious blonde, and what’s her game? The audience figures it out before Charley does. (He’s not too smart. She likes that in a man.)

Tension builds, as Charley’s love for Irene starts to interfere with his obligation toward the honor of the Prizzi family. All is resolved in a conclusion you won’t soon forget. This was a movie that was adored by critics, but perhaps less so by squeamish audiences. Though nominated for eight Oscars, including Best Picture, it won only for Anjelica Huston’s supporting-actress turn as Maerose Prizzi, the Mafia princess spurned by Charley and itching for revenge. Sweet revenge for Anjelica too: the talk had been that she was cast in the film only because she was Huston’s daughter and Nicholson’s girlfriend. Turning in a seethingly angry performance, she fooled them all.

John Huston, of course, is long gone now. Jack Nicholson, once Hollywood’s favorite man- about-town, has not been on screen in a dozen years, and rumors fly abut his physical and mental state. Turner’s still working, notably in TV’s The Kominsky Methodopposite Michael Douglas, but her svelte shape is long gone and her husky voice is now almost a baritone. Happily, Anjelica too remains active, though a lot of her recent work is in voiceover. Time is cruel in the entertainment biz.

June 23, 2022

Playing With Time in “The Big Clock”

Alfred Hitchcock, it is said, was far more interested in suspense than in mystery. Rather than making Agatha Christie-type whodunits, in which we struggle to figure out the identity of the murderer, he focused on the tension surrounding the apprehension of the guilty party. A particular favorite Hitchcock device was that of the “wrong man,” the innocent who’s wrongly accused of a serious crime and must spend the rest of the film trying to shake off those determined to apprehend and convict him.

A 1946 novel proved much sought-after by the motion picture industry because of its elaborate twist on the “wrong man” genre. The Big Clock, by Kenneth Fearing, ultimately became (after several plot changes) a 1976 French crime drama starring Yves Montand, as well as a 1987 political thriller, No Way Out, with Kevin Costner in the leading role. But the film adaptation closest to the original material retained the book’s title, The Big Clock, and cast Hollywood stalwarts Ray Milland, Charles Laughton, and Maureen O’Sullivan as its leads. It was directed by John Farrow (yes, Mia’s father), and overseen by Richard Maibaum, a longtime producer and screenwriter best known today for his work on 13 James Bond screenplays.

Like many a noir-type feature, the screen version of The Big Clock begins near its climax, with Ray Milland’s George Stroud hiding from the law inside an office tower distinguished by an enormous set of international clock faces. Time, as he notes in a voiceover, is not on his side. He’s wanted for murder, and the police are hot on his trail.

Then we flip back a few hours to how it all began. Stroud is editor-in-chief of Crimeways Magazine, part of the Janoth publishing empire headquartered in the skyscraper that boasts the huge clock. So valuable is he to the imperious Earl Janoth (played with his usual outsized presence by Charles Laughton) that Stroud and his wife have never had a proper honeymoon. Now he’s determined to change all that, defying Janoth’s insistence that he give up a sweet little West Virginia getaway to follow up on some true-crime leads that have come his way.

In sticking up for his personal freedoms, Stroud gets sacked, then finds himself in a barroom commiserating with Janoth’s unhappy mistress (Rita Johnson as Pauline York). It won’t be long before she turns up dead, and someone has glimpsed him stealing away from her apartment not long before the discovery of her murder with a blunt object that had recently been in his possession.

The twist is that Janoth, much less interested in Pauline’s death than in the potential for covering an exciting manhunt in his magazines and tabloids, enlists Stroud to track down the killer. We know Stroud didn’t do it; we also know who did. But every clue he uncovers in the line of duty points back to himself as the guilty party. Before poetic justice is finally served in the film’s last few minutes, we see a man unraveling as he comes closer and closer to being apprehended for a crime he didn’t commit. Though there’s a morose take on corporate culture in The Big Clock, ultimately the wicked are punished and the righteous man finds his reward. Which is how the world should work, right?

As always, Milland makes a good hero and Laughton steals the show as his avaricious boss. And, as is so often true, the women are basically just along for the ride. One exception is Laughton’s real-life wife, Elsa Lanchester, as a dotty artist who provides some much needed comic relief.

June 20, 2022

Romancing the Lost City (or Do Romance Novelists Have More Fun?)

A recent airline trip gave me a good excuse to catch up with The Lost City, a much-touted new action comedy in which a reclusive romance novelist finds herself south of the border, fighting off bad guys and finding true love. Starring Sandra Bullock and Channing Tatum, with assists from Daniel Radcliffe (as a weird baddie) and Brad Pitt, it makes a running joke of the low-cut and sparkly fuchsia jumpsuit in which the heroine is kidnapped, and in which she eventually finds herself sprinting through tropical rainforests and plunging down waterfalls. There’s also fun in the fact that Tatum’s character, initially a cover model in a Fabio-like long blond wig, turns out to be less a dashing swashbuckler and more a sensitive guy with a crush on his favorite author.

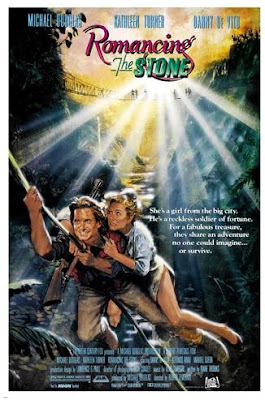

The whole thing was enjoyable airplane viewing, but it made me think back to the original film that successfully blended Latin American adventure with comedy and romance. Of course I mean 1984’s Romancing the Stone, starring Michael Douglas (who also produced) and Kathleen Turner. Both were near the start of their acting careers at the time. Douglas, son of Kirk, was best known for starring as a homicide inspector in TV’s The Streets of San Francisco and for producing (but not appearing in) the Oscar-winning One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest. He began as simply the producer of Romancing the Stone, before deciding to take on the role of the film’s gutsy though slightly goofball vagabond hero. Turner had leapt into the public consciousness as bad-girl Matty Walker in Body Heat(1981). and was mostly being typecast as a femme fatale. Romancing the Stone gave her a chance to stretch as a dreamy, introverted romance novelist who finds herself in over her head after being summoned to the jungles of Colombia. Another member of the cast is Danny DeVito, Douglas’s former roommate and longtime pal, as an inept rogue also vying to find the priceless emerald that is the film’s McGuffin.

A young Robert Zemeckis directed with a light touch, just one year before he became a big man in Hollywood following the release of Back to the Future. But for me the essential part of the team was the film’s screenwriter, Diane Thomas. Thomas enjoyed a Cinderella sort of career in Hollywood, but one lacking a happy ending. She was working as a Malibu waitress, and studying screenwriting through the UCLA Extension Writers’ Program (which employs me to this day) when she managed to slip a copy of Romancing the Stone to Michael Douglas. He read it, loved its razzle-dazzle spirit, and the rest is movie history. The film’s success led to other projects, including the chance to write an Indiana Jones sequel for Steven Spielberg. Alas, in 1985 she was riding with boozy friends on Pacific Coast Highway in the Porsche gifted to her by Douglas when a terrible accident ended her life. For years, UCLA Extension hosted a student screenwriting competition in her memory.

Is Romancing the Stonebetter than The Lost City? That’s hard to say, story-wise. It has no shocking pink “disco-ball” glitter garb, no Fabio-lookalike, and no outrageous Daniel Radcliffe, though it does boast a plethora of crocodiles. Perhaps the big difference between the two is that the earlier film doesn’t seem to be trying quite so hard to give us a rollicking good time. Still, I’m not sure Douglas is right in saying that Romancing the Stone invented a genre that had never before been tried. Maybe it's worth mentioning The African Queen?

June 16, 2022

The Curious Glories of “Morning Glory”

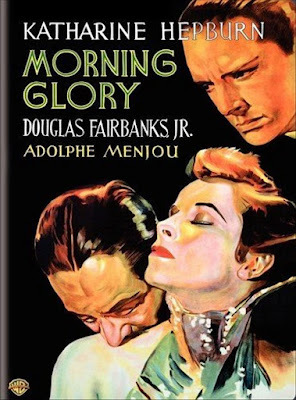

Having recently watched Brad Pitt in the part (in A River Runs Through It) that shot him to fame and fortune, I’ve now found myself marveling at the star-making role of another Hollywood legend. You know her name: Katharine Hepburn. In a nifty compilation of five Oscar-winning DVDS that span the 1930s through the 1950s, I discovered Morning Glory, a behind-the-footlights hit from 1933. Based on a then-unproduced play about an eager young would-be stage actress, it’s not a terribly good motion picture. Hepburn, though, is unforgettable. No wonder the role of Eva Lovelace won her the first of her four Oscars for Best Actress. (Back in that era, there were only three nominees in her category, but still . . !)

Eva, who started out in a rural Vermont town as Ada Love, is now—after some success in a local theatre troupe—trolling for stage roles in New York City. Convinced of her own talent, she tells anyone who will listen about her plans for future stardom. (Marriage is out, because she intends to be embroiled in various magnificent scandals. And, though she longs to take on the great dramatic roles, she’ll refuse any part for which she doesn’t feel a strong personal connection.) In the office of a legendary Broadway producer, played with panache by Adolphe Menjou, she alternates between brashness and a fawning eagerness to please. When he asks her name, she quickly answers, “Eva Lovelace. Like it? I can change it if you don’t.”

The centerpiece of the film is a drunk scene that occurs after Eva’s elderly British admirer, a legendary character actor played by legendary character actor C. Aubrey Smith, takes her to a first-night party at Menjou’s lavish flat, where she mingles with a roomful of elegant society folk. Plainly dressed and emaciated from living on a meager diet, she quickly gets tipsy on two glasses of champagne, after which she trumpets her own genius to anyone within earshot. Suddenly she launches, without fanfare, into Hamlet’s “To be or not to be” soliloquy, followed by a lovely rendering of Juliet in the famous balcony scene. As onlookers titter, she turns downright kittenish toward Menjou: for me seeing the often imperious Hepburn in the throes of girlish infatuation was an unexpected treat.

Morning Glory is a so-called pre-code movie, one made before the infamous Hayes Code of the mid-1930s mandated issues of on-screen morality. But the film’s one instance of outré behavior is so subtle that I nearly missed it altogether. At that eventful first-night party, after finishing her Shakespearean recitation, Eva collapses and is trundled off to the guest room by a butler. Come morning, dialogue hints that Menjou’s character has had his way with a woozy but willing Eva. Feeling guilty (which is certainly to his credit), he cuts off all future contact.

But—wouldn’t you know it?—she finds her pre-destined stardom all the same. Not to mention the love of a talented young playwright, a thankless role for Douglas Fairbanks Jr. The twist is that she’s suddenly unready for this brilliant turn of affairs. In a poignant interchange with a sympathetic wardrobe mistress, she worries about ultimately being a morning glory. (The cautionary title refers to once-bright stage stars who all too quickly fade from view.) Perhaps romantic love and not fame should be enough for her? The ending remains ambiguous, but I sensed that Eva remains Katharine Hepburn to the core. Surmounting her fears, she insists she wants it all.

Historical footnote A updated version of Morning Glory, redubbed Stage Struck, was released in 1958, starring Henry Fonda and Susan Strasberg. Who knew?

Beverly in Movieland

- Beverly Gray's profile

- 10 followers