Beverly Gray's Blog: Beverly in Movieland, page 35

June 14, 2022

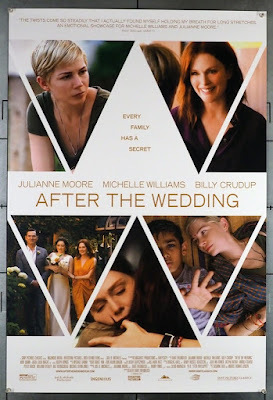

Thoughts from After “After the Wedding”

The Tony Awards, celebrating the best of an up-and-down Broadway season, gave 5 statuettes to a revival of Stephen Sondheim’s Company that flips the gender of key roles, turning Bobby into Bobbie and transforming Amy, the reluctant bride, into Jamie, a reluctant (gay) groom. The switch, made with Sondheim’s blessing and participation, adds new dimension to a show that originally debuted in 1970. I’ve discovered that something of the same switcheroo happened in 2019 when a Danish Oscar nominee from 2006 was turned into an American family drama, written and directed by Bart Freundlich. Because Freundlich has long been married to actress Julianne Moore, it was perhaps natural for him to find a way to star his talented spouse in this project. But it’s also true that the gender switch seems to have enriched the story, perhaps making a sappy situation a bit more interesting.

A caveat: I never saw the Danish original, in which a man (the talented Mads Mikkelsen) returns to his home nation from an orphanage he’s founded in India, only to discover himself face to face with the now-grown child he left behind, as well as the adoptive father who has a secret reason for courting his friendship. Perhaps if I’d watched this much-admired movie, I would have been indignant about the way the story was changed for American audiences. But, knowing nothing of the Danish plot, I completely accepted the fact that an ethereal but ultimately strong young American woman (beautifully played by Michelle Williams) would give up the baby she bore as a teenager, then find spiritual joy in nurturing a passel of orphans in far-off Tamil Nadu. It’s a slow-moving drama, and so there’s a good half hour before she meets with Julianne Moore, the hard-charging New York executive who may be on the verge of giving her orphanage major funding and who surprises her with a last-minute invitation to her daughter Grace’s lavish nuptials.

It's at that wedding that the pieces start coming together. When Isabel, the visitor from India, first sees Oscar (Billy Crudup), the father of the bride, she realizes – as do we -- that he’s her long-ago love, the one who had agreed with her on putting their newborn up for adoption. But the twists, artfully prepared for, keep on coming. As the fragile young bride, Grace, deals with the fact that the mother she thought had died long ago is suddenly here in the flesh, Moore’s character is keeping some secrets of her own.

A man skipping out on a pregnancy, as in the Danish version, is of course not NEW news. I was intrigued by how Michelle Williams’ performance makes it credible that a woman would give away a baby, and then reveal burgeoning—though complex—maternal feeling both toward her Indian orphans and her own adult child. And Moore’s turn as a tough-minded, all-hands-on-deck CEO (one married to a gentle, artistic man) may seem at first like a feminist caricature, but we ultimately discover she has unexpected depths. I also want to give a shout-out to the young woman playing the third crucial female role, that of the barely adult daughter who loves her parents and her new husband, but has probably married much too soon. Abby Quinn is a new name to me, but she’s one to watch. (She also sings, and co-stars in what’s been called a country-music horror film, Torn Hearts, released just weeks ago.)

In a world where men’s stories seem to predominate, both on stage and on screen, it’s refreshing to see women get a chance to shine.

June 10, 2022

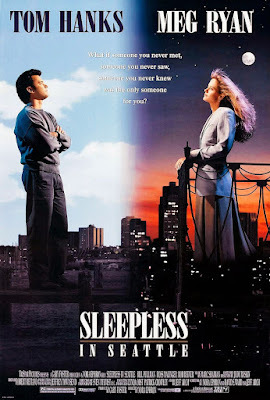

Nora Ephron Slams the Door on Male Chauvinism

We seem to be part of a Nora Ephron revival. Amazon, bless ‘em, keeps reminding me to purchase Nora Ephron: The Last Interview: And Other Conversations. And June 7 was the publication date for a new biography by Kristin Marguerite Doidge, simply titled Nora Ephron: A Biography.

Doidge’s lively book is an apt tribute to a screenwriter, director, novelist, essayist, and all-around bon vivant who looked at the world wryly, but never let romance go out of her life. Though Ephron left us in 2012, after a rare blood disorder with an unpronounceable name turned into leukemia, her ebullience and can-do spirit continue to inspire. Boy, do we need her now!

Nora was the oldest daughter in a family of writers. Her parents, Henry and Phoebe Ephron, collaborated on a hit Broadway comedy, Take Her, She’s Mine, about a father learning to let go of his blossoming young daughter. It wasn’t exactly autobiographical, but as the eldest of four daughters in the Ephron household, Nora could see some of her own Wellesley experiences playing out on stage (after all, they did use direct quotes from her letters home!). The Ephrons also enjoyed a long Hollywood screenwriting career, culminating in an Oscar nomination for Captain Newman, M.D. But their artistic success didn’t make for a happy marriage, given that it was fueled by alcoholism and infidelity. Though Phoebe famously told her brood to mine their private lives for artistic material – “Everything is copy”—she was secretive about her own deep unhappiness.

Nora, for her part, grew up determined to make her own way as a writer. Maybe it was the fact that she was named after the heroine of Ibsen’s A Doll’s House, the one who climactically slammed the door on a life of domestic subservience, but she never stopped fighting for what she wanted. Starting out as a journalist, she eventually won the battle to be accepted in an industry that had long avoided hiring women. In 1976, she married Carl Bernstein of Watergate fame, but the union fell apart when (about to give birth to her second child) she discovered his long-term affair with the daughter of a British prime minister. Eventually she recovered enough from this shock to write a close-to-the-bone but hilariously funny novel, Heartburn, then adapted it for the 1986 film directed by Mike Nichols.

By that point, she had already transitioned to Hollywood, writing a powerful true-to-life screenplay for Silkwood with her friend and fellow journalist Alice Arlen. That 1983 drama about the gutsy whistle-blower at a nuclear plant earned five Oscar nominations, including one for Ephron and Arlen. The director was Mike Nichols, who became one of her many close friends, as well as a mentor for her moviemaking dreams. Mike’s guidance as well as her own courage and passion for detail led her into directing her own work. Calling upon the comedic flair she’d shown in everybody’s favorite romcom, 1989’s When Harry Met Sally . . . (helmed by Rob Reiner), she directed such hits as Sleepless in Seattle and You’ve Got Mail. Not everything was a winner—the screwball antics surrounding a Venice, CA crisis hotline on Christmas Eve in Mixed Nuts don’t really land—but her string of box office and critical successes would make anyone proud. Meanwhile, she wrote Off-Broadway and Broadway plays and had several bestselling collections of essays, including I Feel Bad About My Neck: And OtherThoughts On Being a Woman.

Her last film, 2009’s Julie & Julia, called upon her passion for cooking and for eating. As a person who couldn’t order in a restaurant without requesting elaborate changes to the standard fare, Nora Ephron knew exactly what she wanted. Too bad she isn’t still among us. As for me, I’ll have what she’s having.

Attention, Angelenos: Kristin Marguerite Doidge will be appearing at 7 p.m. g on Tuesday, June 14 at Book Soup (8818 Sunset Blvd.,) to discuss Nora Ephron: A Biography. I’ll be on hand to conduct a Q&A with Kristin. Y’all come!

June 7, 2022

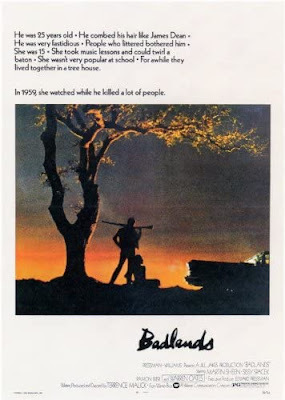

“Love is Strange”: Terrence Malick’s “Badlands”

In the wake of 1967’s Bonnie and Clyde, Hollywood became fascinated with stories of young lovers on the run, fleeing from crimes they’d committed in the heat of passion. I’ve finally seen one of the best of these, 1973’s Badlands. It was based on the actual story of drifter Charles Starkweather, who was executed at age 20 for murdering eleven Midwesterners circa 1958, and his companion, Caril Ann Fugate, who threw in her lot with him at age fourteen. Grim subject matter, to be sure, but this film marked the directorial debut of Terrence Malick, whose stop-and-start career has produced a modest number of exquisite feature films, sometimes with twenty-year gaps between them. (Today, if IMDB is to be trusted, he’s busy with short films and documentaries.)

Though Malick’s output is rather limited, his films have a visual and emotional impact that makes them memorable. The loss of innocence is for him an essential subject, no more so than in Badlands, which is narrated by Sissy Spacek, at the beginning of her long career. (Though about 22 at the time, she easily comes across as the fifteen-year-old Holly, the film’s stand-in for Caril Ann Fugate.) Her voiceover narration, a frequent feature of Malick’s work, is delivered in the flat, matter-of-fact, almost shell-shocked tones of someone who can’t truly process the horrors she’s seen. Holly, we feel, is a good girl at heart, but one so benumbed by boredom and loneliness in a small Dakota town that she easily falls in with the dangerous Kit Carruther (Martin Sheen) because he resembles James Dean. It’s a strong reminder of the power of movies to shape young lives.

Bonnie and Clyde robbed banks for money and for excitement. Kit, a philosopher at heart, has no particular use for money, but he finds his excitement in aiming his pistol and firing at whatever (or whomever) gets in his way. This includes his sweetheart’s father, and several good Samaritans. Lean and hungry-looking, Kit is tender to Holly but quickly brutal to everyone else. The role is a strong follow-up to Sheen’s screen debut as a thug terrorizing the occupants of a late-night New York subway car in 1967’s The Incident. Looking back on it, his persona in those early days was a far cry from the gravitas of his more recent roles, like that of the U.S. President in The West Wing.

In what was to become typical of Malick films, most of the action is set outdoors, in a lush natural setting. The production designer was Jack Fisk, a future Oscar nominee who would marry Sissy Spacek the following year. (Remarkably for a movie couple, they’re still together, living on a farm near Charlottesville, Virginia.) Fisk started out making low-budget features for Roger Corman, as did Badlands’ ace cinematographer, Tak Fujimoto, who went on to shoot both The Silence of the Lambs and Star Wars.

Another Malick predilection is to score his tough-minded, deeply contemporary movies with elegant classical music, conveying a sense that the story somehow exists outside of time. Badlands contains snippets of Eric Satie and Carl Orff, along with a dreamy Nat “King” Cole ballad and Mickey & Sylvia’s period-appropriate “Love is Strange.”

That last is a key takeaway from Badlands. Love definitely leads Kit and Holly in strange directions. The film’s title, by the way, refers to a bleak but picturesque region of South Dakota that the characters see in the distance but never quite reach. An apt metaphor, of course, for the lethal aimlessness of life for two drifters who don’t quite know what they want or need.

June 3, 2022

Running On About “A River Runs Through It”

A River Runs Through It is a 1992 film, the third directed by Robert Redford, that bears some superficial resemblance to East of Eden, the 1955 screen adaptation of John Steinbeck’s famous novel. In telling the tale of two brothers, their rivalry, and their fraught relationship with their stern father, Steinbeck was evoking perhaps the most famous sibling rivalry of them all, that between Cain and Abel. His Cal and Aron vie for their father’s approval and for the love of the same girl, with tragic results.

In its closing credits, A River Runs Through It includes the usual disclaimer that this is a work of fiction, and that resemblance to any actual person is strictly coincidental. In point of fact, though, the film is based on a 1976 novella by Norman Maclean, a college professor who was inspired by his own family history. Like Steinbeck, he writes about two brothers, exploring their differences as well as their strong sense of kinship. He sets his tale not in the rural Salinas Valley but in the piney woods and fast-flowing streams of Missoula, Montana. And though their father might seem strict at times, he is by no means the unbending patriarch that Steinbeck portrays. Instead he’s a Presbyterian minister of Scottish descent, one who counts fly fishing as an intrinsic part of the family’s religious values.

In a story pitting brother against brother, the rebel is always the more interesting of the two. This was certainly so in East of Eden, where the role of Cal brought James Dean a posthumous Oscar nomination. As younger brother Paul Maclean in A River Runs Through It, Brad Pitt is the one you can’t stop watching. Unlike Cal, Paul is not a rebel without a cause. He and his older brother, the far more scholarly Norman, feel a deep emotional bond, especially when they’re casting off in a trout stream. Paul is charming and lovable, without a doubt. But he is the one who refuses to conform, refuses to play it safe, craves the excitement of living on the edge. Ultimately he’s asking for trouble—and gets it. In his first major role, just a year after making a small splash in Thelma and Louise, Pitt shows he’s on his way to stardom.

But for me, in a way, the bigger revelation was the actor who plays the boys’ father. Back in 1974, as a Roger Corman peon, I had never heard of Tom Skerritt when he was cast in a featured role in Big Bad Mama. As rogue and petty criminal Fred Diller in this Depression-era caper film, he robbed banks and romanced Angie Dickinson, before she moved on to the more mature William Shatner and he moved on to her two nubile daughters. It was an exuberant performance, and Skerritt also had fun behind the scenes, finding ways to knock Shatner’s toupee askew. But, speaking to Skerritt on-set, I learned he had just switched agents, and aspired to bigger and better things. One came along in 1979, when—as captain of the Nostromo—he was assumed to be the eventual sole survivor in Alien . . . until his death shocked the moviegoing world. He was featured in Top Gun and many another action flick, while also taking on a dad role in Steel Magnolias.

But none of this prepared me for seeing him as a small-town minister with well-defined values, a passion for fishing, and two rambunctious boys in need of guidance. Well done!

Crazy credit: "No fish were killed or injured during the making of A River Runs Through It"

May 31, 2022

Undressing “Dressed to Kill”

Here there be spoilers.

Watching Brian De Palma’s Dressed to Kill, a popular erotic thriller from 1980, I found myself remembering my Roger Corman years. Why? First, because the executive producer on Dressed to Kill was Samuel Z. Arkoff, who with James Nicholson had led American International Pictures, the company that taught Corman how to make movies fast and cheap for the drive-in market. Secondly, one of the big-name stars of Dressed to Kill is the drop-dead gorgeous Angie Dickinson, as a wife and mother eager for sexual kicks and kinks. When I worked for Corman’s New World Pictures in 1974, Angie starred in the sexy Big Bad Mama, showing off a beautifully toned body and a good-natured willingness to bare it on-set. (I suspect the franker version of Dressed to Kill that I just watched on video employs a body double for the scene in which Angie’s character graphically masturbates in the shower. Who could blame her for backing away from that sort of intimate reveal? But I still give her props for her willingness to approach material that is frankly erotic.)

The third reason that Dressed to Kill makes me think of my Corman days is that, in the wake of Fatal Attraction (1987), we at Concorde-New Horizons became enamored with the idea of producing our own erotic thrillers. Our Body Chemistry (1990), featuring a female medical researcher with perverse sexual proclivities, soon followed. But we also borrowed from De Palma’s work a title and some of his film’s more prurient kinks. The result: 1987’s Stripped to Kill, directed (and co-written) by a feisty young woman named Katt Shea. The official description tells the tale: “When Detective Cody Sheehan discovers the body of a stripper from the Rock Bottom dance club, she wants the case. But the only way Cody can get the assignment is to go undercover—uncovered—at the club.”

Strippers and killers turned out to be such a lucrative combination that we went on to make Stripped to Kill 2: Live Girls, as well as Dance of the Damned (a not-so-brief encounter between a vampire and a stripper). We also shot Midnight Tease (in which I have a minor role), before hanging up our g-strings for good.

There are, I hasten to add, no strippers in Dressed to Kill. But aside from Dickinson’s hot-to-trot housewife, the film features De Palma’s brand-new spouse, Nancy Allen, as a prostitute who helps track down her killer. And then there’s the tall, mysterious blonde who seems to have lethal intentions toward both women. Who is this blonde when she’s at home? Let’s say Bobbi, and leave it at that.

Without trying to blurt out the film’s secrets, I’ll simply assert that Dressed to Kill would not be made today, at least not in its current form. Many have accused it, in the words of the ever-smart Wikipedia, of perpetuating the myth that trans people are sexual predators caught in the grip of mental illness. Writing in The Guardian in 2020, critic Scott Tobias referred to De Palma's grasp of trans issues as "disconcertingly retrograde . . . There's no getting around the ugly association of gender transition with violence, other than to say that it feels thoroughly aestheticized. ”

De Palma admits that times have changed. He still insists, though, that the film has long been a favorite of the gay community, partly for the aesthetic flamboyance of its cinematography and the high pitch of its emotions. You’ll find Stripped to Kill full of all of that as well. At Corman’s we learned to be terrific copycats.

May 27, 2022

Confronting Death in Venice

You don’t expect a film called Death in Venice to be cheery. And of course this 1971 adaptation, by Italy’s great Luchino Visconti, of a Thomas Mann novella does stay true to its title. So there aren’t a lot of laughs here. Still, it’s an exquisite rendering of Mann’s story about a celebrated artist who falls prey to a vision of newly ripe male beauty. What I hadn’t remembered is that this work is set during the throes of a pandemic. It’s cholera, not COVID, that’s haunting the streets and canals of Mann’s turn-of-the-century Venice, but that sense of approaching doom is something we all know quite well.

Visconti, who collaborated on the screenplay as well as directing, made one significant change, turning Mann’s central character, Gustav von Aschenbach, from an author to a composer. He also gave his von Aschenbach, played with clenched intensity by British actor Dirk Bogarde, something of a backstory. Visconti’s von Aschenbach, has (or had) a loving young wife and little daughter. He also has a friend, a fellow aesthete, who insists that his music would be more vibrant if he were to let go of his usual self-discipline and try boldly challenging the boundaries of high art. Since Death in Venice is a subjective piece, filtered through von Aschenbach’s memory and imagination, some of the scenes playing out on screen could not have happened. And elsewhere there’s a surreal quality (a strange gondolier, a ghastly group of laughing entertainers) that helps make von Aschenbach’s solitary stay at a grand old beachfront hotel on Venice’s Lido particularly ominous.

It's at that hotel that von Aschenbach first spots a slender boy in a sailor suit. This boy, a young teen with golden curls, is part of an entourage that includes a stylish mother and several modestly dressed little girls. They speak amongst themselves in Polish, obviously looking forward to a genteel seaside holiday. Instantly the boy, Tadzio, becomes von Aschenbach’s obsession. Entranced by his beauty—reminiscent of a slim young Greek statue—von Aschenbach takes to shadowing him, following the group onto the beach and into the Venetian streets, where remnants of disinfectant hint at a health crisis no one is officially willing to discuss.

That’s pretty much the story, until its grim conclusion. Von Aschenbach lurks, passes Tadzio in corridors, thinks of speaking (but does not), fantasizes warning the family away from the coming plague, generates in the young man a fleeting wisp of a smile. Tadzio is so crucial to the story that the DVD of the film (beautifully restored to show off Visconti’s pastel palette) contains a featurette on the search for the young actor who will fill this nearly silent but essential role. Visconti, certain he will not locate in Italy the young blond godling described by Mann, travels through Europe to find his prize. He visits schoolchildren in Poland and Romania, then heads for Scandinavia to scout out blue-eyed blonds. In Sweden, interviewing young actors (ideally about age 12), he discovers fifteen-year-old Björn Andrésen, whose tousled curls and classic features make him stand out. Worried that he’s too tall, Visconti keeps looking. Ultimately, though, Andrésen gets the job.

Be careful what you wish for. Andrésen is perfection in the role, but his life would never again be the same. Promoted in the press as “the most beautiful boy in the world,” he’s worked hard over the years to dispel rumors about his sexuality. Andrésen has said, “My career is one of the few that started at the absolute top and then worked its way down. That was lonely.”

May 24, 2022

A Portrait of “The Duke” (No, NOT John Wayne)

That’s the great thing about British actors: you can always count on them to put on a jolly good show, especially when they’re portraying common folk from the provinces. The unfortunate thing is that you can’t always understand what they’re saying. Those working-class North of England accents are just too thick to allow an American to catch every delightful word.

It’s worth it, though, to see Jim Broadbent portray a cranky taxi driver from Newcastle upon Tyne, with Dame Helen Mirren shedding her usual glamour to play his exasperated wife. Broadbent’s Kempton Bunton is a World War II vet, circa 1961. Neglecting his job, he’s now spending most of his energy on a quixotic campaign to end government laws that require citizens to purchase a license in order to watch the telly. While his wife Dorothy scrimps and scrubs as a housekeeper for a more upper-crust family, he continues his fiery one-man crusade, eventually getting thrown in the clink. It’s not that he can’t personally afford a license, he insists. He’s campaigning on behalf of the common folk, especially the elderly and military veterans, who haven’t the wherewithal to tune into the BBC.

Behind his shenanigans (he’s also taken up playwriting) is a sad family story: a teenage daughter has died in a bicycle accident, and he blames himself for gifting her the bike. So what may seem like a quirky comedy is in many ways a film about grief and the different ways it affects those who’ve suffered terrible losses. That’s part of what’s pulling husband and wife apart, making her angrily stoic and him expansively emotional.

The story as we see it on-screen hinges on a late Goya portrait of the Duke of Wellington, on temporary exhibit at London’s National Gallery. When this art treasure ends up in Bunton’s hands, he hides it in the back bedroom of his row house, planning to use the reward money to carry on his activism. Instead he’s hauled into court, charged with grand theft and a host of other major crimes, and faces a serious prison sentence.

What’s fascinating is that the story of Kempton Bunton and the Duke (the one a commonplace man, the other a powerful aristocrat) is entirely true. It was brought to the producers’ attention by Bunton’s grandson: he never knew his grand-dad, but was in possession of family artifacts as well as family secrets, and insisted that the script of The Duke stay true to what actually happened. According to an instructive article in the Los Angeles Times, every scene and every character detail of the subsequent film accurately reflect the Buntons’ own actual behavior. Family possessions, like a photo of the deceased daughter, were used as key pieces of set dressing. So I can assume that the sweet moment when husband and wife put aside their grievances and spontaneously begin to dance together in their modest kitchen did not come out of a screenwriter’s fertile imagination, but rather indicates something about the private lives of this usually warring pair.

Why is a small film like this one worth making—and worth seeing? We all love grand movies that unleash the power of spectacle. The big screen is possibly at its best in giving us big vistas and big emotions. But the joys and sorrows of everyday people can be equally worthy subjects. As my favorite multiplex disappears (yes, another victim of COVID), I’ll remember watching The Duke in a real movie theatre. It’s not an experience I hope to replicate anytime soon.

May 17, 2022

The Ballad of Joel and Ethan Coen

The indefatigable film historian Joseph McBride has now tackled the work of my favorite filmmaking duo, Joel and Ethan Coen. Having written his share of huge door-stop biographies (Frank Capra, John Ford, Billy Wilder, et al), Joe is now devoting himself to critical assessments of some of Hollywood’s then-and-now greats. The new book is a slim volume called The Whole Durn Human Comedy: Life According to the Coen Brothers.

I turned back to McBride’s book recently after having watched one of several films that the Coens wrote but did not direct. A British TV movie called Gambit (2012), dealing with high-stakes shenanigans in the London art world, seems to contain the brothers’ trademark blend of suspense and black humor. Starring a stellar cast from both sides of the pond—Colin Firth, Alan Rickman, Stanley Tucci, Cameron Diaz—it promised to be an enticing romp, along the lines of their Intolerable Cruelty. Unfortunately, without Joel and Ethan’s deft directorial touch, the film seems less buoyant than leaden. The plot (as overseen by director Michael Hoffman) twists and turns, but to little avail. McBride is right when he generalizes that “Coen scripts directed by others tend to go disastrously awry.”

When the Coens are in charge of their own turf, though, odd and wonderful things happen: like Fargo, and Blood Simple, and Barton Fink, and Inside Llewyn Davis and O Brother, Where Art Thou? (The last of these is a clear nod to a key influence on the Coens, Preston Sturges’ Sullivan’s Travels, which argues the importance of comedy in chronicling the often-dark human condition.) But there are many—both moviegoers and critics—who consider Joel and Ethan taciturn and cynical, and it is they whom McBride is addressing in this book. He begins each chapter with a common complaint about the brothers’ films, then artfully proceeds to debunk it. Are they, for instance, the heartless cynics whom their detractors decry? Are they too fond of caricature, especially ethnic caricature, as seen in the satiric portrayals of Jewish Midwesterners in A Serious Man? Discussing that film as well as The Big Lebowski and the Southern caricatures that abound in O Brother, Where Art Thou?, McBride labels the Coens “equal-opportunity mockers.” Are they lacking in empathy for their characters? Or overly fond of a bleak nihilism that reveals their contempt for any sort of belief system? McBride’s in-depth discussions of Fargo and No Country for Old Men help disprove these claims.

McBride ends his book with an unexpected chapter called “’Magic*Mirth*Mystery” in The Ballad of Buster Scruggs.” I enjoyed the 2018 film, an anthology-style collection of 6 Western tales, but never stopped to think of it as a compendium of the brothers’ previous concerns. But McBride insists that “like such films as John Ford’s The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance, Carl Dreyer’s Gertrud, and Orson Welles’ The Other Side of the Wind, Buster Scruggs is a distillation of the Coens’ work, an eccentric, allegorical, and often nakedly emotional presentation of the filmmakers’ deepest thoughts and feelings.”

The film opens with a segment in which the Coens exercise their fondness for parody and meta filmmaking. Here is a lampoon of the singing-cowboy trope, calling in every cliché of classic Westerns, including the gunfight in the main street of a sad prairie town. But as the film moves forward, it enters much darker territory, focusing on human cruelty and violent death. Its final chapter, which hints at the Afterlife, circles back mordantly to the film’s opening, with its mock-elegiac Western ballad, “When a Cowboy Trades His Spurs for Wings.” Brilliantly macabre fun!

May 12, 2022

A Salute to Two Jolly Good Fellows

I never met the late Robert Morse, who recently passed away at age 90. But I saw him onstage in his breakout Broadway hit, How to Succeed in Business Without Really Trying. In this bouncy but pointed Frank Loesser musical satire, which won the 1962 Pulitzer Prize for drama, Morse combined his skills as a song-and-dance man with the personal charm that radiated through his every role. In portraying J. Pierrepont Finch, who rises from window washer to chairman of the board of the World Wide Wicket Company, Morse parlayed his trademark combination of innocence and chutzpah into a long. lively career. After winning a Tony for his portrayal, the gap-tooth Morse transitioned to Hollywood, starring in the screen version of How to Succeed and also appearing in several parts that traded on his distinctive presence. He was featured as a naïve, bereaved young Englishman in The Loved One, a satire of the California funeral industry, while also appearing in such Sixties dark comedies as A Guide for the Married Man, Where Were You When the Lights Went Out?, and Oh Dad, Poor Dad, Mamma’s Hung You in the Closet and I’m Feelin’ So Sad. (It was the era of long titles.)

Once these youthful roles dried up, he went back to Broadway to don Jack Lemmon’s frocks and heels in Sugar, an attempt to transfer the magic of Some Like It Hot to the musical stage. As he aged, he tried on more mature but still whimsical roles, like that of the Wizard in Wicked. His greatest stage success in his later years was playing Truman Capote in a one-actor play, Tru. But TV lovers in this century of course cherish his appearances as Bertram Cooper, the eccentric, sometimes mystical ad agency partner in Mad Men. His on-screen death (while watching a man walking on the moon) is followed, remarkably, by a fantasy sequence in which—surrounded by chorus girls—he cheerily croons “The Best Things in Life are Free.” What a way to go!

David Birney never reached the same pinnacle of fame as Robert Morse, but I mourn him too. It’s especially sad that this dedicated actor and intellectual died of Alzheimer’s disease, at the age of 83. I first became aware of Birney in 1972, with the debut of a well-intentioned TV sitcom called Bridget Loves Bernie. The show, an update of the old Broadway chestnut, Abie’s Irish Rose, focuses on the marriage of a nice Catholic girl (Meredith Baxter) and a nice Jewish boy. Of course the in-laws aren’t happy, and hilarity ensues. Though the show was innocent enough in its intentions, it was rife with stereotypes, and many Jewish communities, worried about high rates of assimilation, were not amused. The fact that Birney’s background was in no way Jewish hardly made the naysayers any happier.

Once the show was cancelled, Birney continued on with stage and TV roles. In 1988 he signed on for one of Julie Corman’s most ambitious projects, a screen adaptation of Issac Asimov’s outer-space story, “Nightfall.” It’s a brilliant story in concept, but it’s extremely short, so writer-director Paul Mayersberg tricked it out with details of an exotic extra-terrestrial civilization and a lot of bad wigs. While we were making the film, I somehow met with David at a local spot called the Brentwood Country Mart for a chat. He lent me a wonderful book by the actor/writer Simon Callow called Being an Actor, and I’ve since bought it for my home library. David was serious abut his craft, and I’m sorry his life didn’t permit him more triumphs.

May 10, 2022

When a House is Not a Home: Exploring Polly Adler’s Follies

A House is Not a Home was a 1964 drama that brought in lousy reviews and mediocre box-office, despite the Oscar-nominated costumes of Edith Head as well as a theme song by Burt Bacharach and Hal David that has become a standard. This loose dramatization of Polly Adler’s storied life as the madam of a New York bordello starred Shelley Winters. Such Hollywood favorites as Robert Taylor, Cesar Romeo (as gangster Lucky Luciano), Broderick Crawford, and Jesse White all had featured roles. In the early Sixties, with the old Production Code heading for its final fadeout, Hollywood was starting to explore the implications of sexuality, and the role played by sex in the power-struggles of the era. But artistic timidity was still the rule, and the film focused much of its attention on Polly’s own love life. It was, clearly, a far cry from Adler’s own memoir of the same name, a frank look back at how a very young Jewish immigrant from a Russian shtetl—forced to make her way in NYC—discovered that by running a classy brothel catering to mobsters and politicians she could carve her own rich slice of the American pie.

I bring all this up because my colleague, Debby Applegate, has recently published Madam: The Biography of Polly Adler, Icon of the Jazz Age. Applegate, who won the Pulitzer Prize for her biography of the Reverend Henry Ward Beecher, enjoys writing about subjects whose sexual escapades are outside the pale. She depicts Polly Adler as moving quickly from girlish innocence to a matter-of-fact acceptance of mankind’s sexual proclivities. And she focuses on Adler’s contributions to an age when mobsters and politicians (including the on-the-rise FDR) would meet and mingle at a swanky brothel, along with such members of the press as Robert Benchley and Walter Winchell. It makes for fascinating reading.

Some of Polly’s “girls” (like the perennial sarong-clad Dorothy Lamour) went on to legitimate showbiz careers. Which led me to think about the ways in which the two professions overlap. No, this isn’t a critique of the moral lapses of actresses, although historically women who made their livings on the stage were widely assumed to be morally compromised. But prostitution, after all, is a career that requires acting skills. Jane Fonda makes this point during her performance as a call-girl in 1971’s Klute: “For an hour I’m the best actress in the world.”

Fonda won a Best Actress Oscar for this role. The Hollywood Reporter not long ago published a list of all the Hollywood actresses who’ve nabbed Oscar nominations for representing on screen what the magazine calls “The Oldest Profession in Oscar History.” The list contains almost twenty names, and many of them have been winners, everyone from Greta Garbo in 1930’s Anna Christie to Kim Basinger in L.A. Confidential (Best Supporting Actress, 1997) and Charlize Theron in Monster (2003). The roles fall into several categories. There are the exuberant “happy hookers” (see Melina Mercouri in Never on Sunday, Shirley MacLaine in Irma la Douce, and of course Julia Roberts in Pretty Woman, the film that inspired a lot of young girls to think that prostitution was a pretty swell career move. By contrast there are the sufferers, like Shirley Jones who won a Best Supporting Actress Oscar for 1960 for Elmer Gantry, in which she played against type by portraying a fallen woman taking revenge on the man who had despoiled her. Never, though, have I seen on screen a Polly Adler type, someone whose down-to-earth acceptance of carnality makes her a power broker in her own right. One day, perhaps?

Beverly in Movieland

- Beverly Gray's profile

- 10 followers