Beverly Gray's Blog: Beverly in Movieland, page 126

November 5, 2013

Old Folks at Home: The Motion Picture & Television Fund Retirement Home

Quite a coincidence. On Friday, I went to the Ahmanson Theatre to see Taxi alumni Danny DeVito and Judd Hirsch in a new production of Neil Simon’s old chestnut, The Sunshine Boys. This tale of elderly vaudevillians, which won an Oscar for George Burns in 1977, builds to a climax when one characters considers moving to a home for ageing actors. That suburban facility sounds like a comfortable place to wait out one’s waning years. But still – it’s New Jersey, not Manhattan’s Great White Way, so for a thespian it’s clearly a last resort.

Then on Saturday I addressed the San Fernando Valley branch of the California Writers Club. Where do they meet? At the Wasserman campus of the Motion Picture & Television Fund in Woodland Hills, where Mulholland Drive meets Spielberg Way. This beautifully landscaped MPTF enclave, established by actor Jean Hersholt in 1940, today serves as a retirement home for members of the film community who have nowhere else to go.

Strolling the grounds is like walking through Hollywood history. The most recent buildings, sleek and airy, date back to the start of this century. These include the imposing Fran & Ray Stark Villa, with its attractive dining facility. Nearby are several Katzenberg Pavilions which provide meeting and recreation space. Then there’s the Saban Center for Health and Wellness, featuring the Jodie Foster Aquatic Pavilion.

Older residential and administrative buildings also honor Hollywood figures. One low-slung apartment block bears a plaque labeling it as “Hopkins’ Haven,” lovingly presented by Sir Anthony Hopkins’ mother, Muriel, and the Motion Picture Mothers. Perhaps the most charming structure is the cozy John Ford Chapel, inspired by George Washington’s chapel at Mt. Vernon and transported from Ford’s ranch to the MPTF site. The chapel interior is embellished by lovely stained glass windows. The altar is set for a traditional Christian service, but there are also Jewish symbols, plus a mezuzah on the doorpost.

Statuary graces the grounds, sometimes in unexpected places. A welcoming presence near the entrance is a larger-than-life work depicting Charles “Buddy” Rogers, the musician-actor husband of Mary Pickford, playing a trombone. It’s adapted from a smaller piece by actor George Montgomery, who was also a self-taught sculptor. Elsewhere you can find a bust of old-timer Charlie Ruggles, a well-liked comic actor who appeared in films from 1914 until his death in 1970.

But the centerpiece of the grounds is the remarkable Roddy McDowell Rose Garden. McDowell had been a supporter of the Motion Picture Home since he first visited in 1942, as a lad of fourteen, fresh from starring in his first American film, How Green Was My Valley. His death inspired a living tribute by his many female friends in Hollywood., who were determined to capture the spirit of the garden he loved at his English country home. The campaign was spearheaded by four women: designer Joan Axelrod, Lauren Bacall, Sybil Burton Christopher, and Elizabeth Taylor. (The last two were both married to Richard Burton, and I suspect they rarely found themselves working side by side.) Supporting the effort were almost 100 so-called “Roddy’s Girls,” including such assorted luminaries as Julie Andrews, Jamie Lee Curtis, Deanna Durbin, Jane Fonda, Nancy Sinatra, Sharon Stone, and Joanne Woodward. The roses, on a sunny November afternoon, were lovely. But the garden’s most striking feature is a giant Caesar statue, honoring McDowell’s role in Planet of the Apes.

The property is not without controversy: the sudden closure of a hospital facility circa 2009 caused residents much grief. But on a bright day in early fall, what a lovely place to contemplate growing old.

Published on November 05, 2013 09:41

October 31, 2013

Halloween Among the Magnolias

Halloween should be a wild and crazy night in Magnolia Park. When I visited in late September, this lively section of Burbank (on Magnolia Blvd., east of Hollywood Way) was already gearing up for haunted holiday fun. Yummy Cupcakes was touting “Spooktober – 31 Days of Monstrous Cupcakes,” and the various funky vintage clothing boutiques were luring customers with racks of trick-or-treat-worthy finery. I was in Magnolia Park to visit Dark Delicacies, which calls itself the Home of Horror. (It specializes in scary books and videos; owners Del and Sue Howison are huge fans of my Roger Corman: Blood-Sucking Vampires, Flesh-Eating Cockroaches, and Driller Killers.) At Dark Delicacies, it’s Halloween all year ‘round. The same clearly holds true for Halloween Town, a neighboring business crammed so full of elaborate monster memorabilia – like the skeleton of a two-headed baby -- that it had to move its costume store to a separate building down the street.

It’s fitting that Magnolia Park is bordered by Hollywood Way, because there’s something very Hollywood about this stretch of the middle-brow city of Burbank. Shoppers who venture here are looking for something outlandish, like an antique lamp or a retro evening gown. Even the names of the stores – Junk for Joy, Pimp My Pooch, Hubba Hubba (which advertises “1930s thru 60s Cool Stuff for Guys n’ Dolls”) – suggest the notion of shopping as entertainment. There’s also a spray tanning spot called Blush, as well as a salon with the monicker Wax Poetic. The area offers edibles too, of course, ranging from the healthy to the gooey. Rocket Fizz bills itself as an old-fashioned soda and candy shop. The last Friday of the month has become Magnolia Park’s official Ladies' Night Out, complete with discounts, music, wine, food trucks, and henna, to suit the tastes of hip women on the go.

Along with all the recreational shopping opportunities, Magnolia Park seems to specialize in services for those with showbiz aspirations. This isn’t a huge surprise, since Burbank is the home of Disney, Warner Bros., and many movie and TV production companies. It’s a Wrap thrift shop offers what it calls “production wardrobe sales,” geared to those who covet Hollywood fashion sense. (Maybe you too can dress like Don Draper!) The Awards Studio advertises media make-up classes. A print shop announces its rates for script copying. Elsewhere, beneath a sign that proclaims “Studio Rental by the Hour,” there are spaces available for film shoots, casting sessions, props and wardrobe storage.

Right next door to Dark Delicacies is a business that caters totally to movie folk. The Writers Storeis the place where I first – circa 1983 -- touched a computer keyboard and heard the magic word Microsoft. For years it was located on Westwood Blvd. in West Los Angeles, but now it’s firmly ensconced in Magnolia Park. The Writers Store is the place to go when you want to buy movie-related software, browse how-to-write-a-screenplay books, take classes, or sign up for a consultation with a technology expert. Tell Mario I said Hi.

I’m not sure how the Writers Store plans to celebrate Halloween, but there’s no question that Dark Delicacies will be going all out. So will Halloween Town and 8-Ball, which sells old movie posters and vintage horror art. And next year at this time they’ll be joined by Creature Features, where you can buy a kit to build your favorite monster. If you like things that go bump in the night, it’s clear Magnolia Park is the place to be. Even if there’s not an actual magnolia tree in sight. Which makes things perhaps even spookier.

Published on October 31, 2013 11:39

October 29, 2013

“Cut to the Chase: The Wit and Wisdom of UCLA Extension Screenwriters

Despite what you might have heard, most screenwriters don’t lead glamorous lives. In Hollywood they’re a lot like Rodney Dangerfield: they get no respect. Even when a writer is lucky enough to sell a screenplay, it often gets rewritten to the point of being unrecognizable. That’s because everybody – the producer, the director, the star, the producer’s girlfriend – wants to have a hand in shaping the final draft. Especially these days, the original ending may wind up being scrapped if it doesn’t test well with a preview audience. And all too many movies bear the stamp of being designed by committee.

Many’s the writer who finds himself (or herself) barred from the set. That was the case with Diane Lake, who wrote the original draft of the Oscar-nominated Frida, the Frida Kahlo biopic (starring Selma Hayek) that won two Oscars and was nominated for four more. Lake also had to survive a messy arbitration process involving her writing credit on the film, along with competing claims from several others who contributed to the shooting script.

Still, creative people continue wanting to write movies. And UCLA Extension’s world-famous Writers’ Program is there to help make it happen. I’ve been fortunate to teach in the Writers’ Program since 1995. That’s where I first met Diane Lake, along with a host of talented screenwriters who are also gifted teachers. We teach in classrooms on the UCLA campus; we teach at satellite campuses spread across the L.A. area. And, more and more, we teach online, educating students all over the world about the art and the craft of screenwriting.

Now the ever-enterprising Linda Venis, director of UCLA Extension’s Department of the Arts, has compiled a new handbook tailor-made for aspiring screenwriters. Its full title is Cut to the Chase: Writing Feature Films with the Pros at UCLA Extension’s Writers’ Program. A number of prize-winning instructors have contributed chapters that nicely demystify the screenwriting process. I read the book with great pleasure, enjoying practical tips on such matters as how to get started, how to use note cards to structure a story, how to shape scenes, and how to know when your work is finally finished. There are plenty of vivid examples, many of them culled from recent films. (The King’s Speech is a particular favorite.) And several chapters offer exercises I wish I’d thought of myself. Philip Eisner’s contribution, “’Show, Don’t Tell’: Visual Screenwriting,” includes an exercise borrowed from the novelist John Gardner. Eisner habitually asks his students to “write a brief character sketch, using objects, landscape, weather, etc., to intensify the reader’s sense of the character. . . . The students must limit their descriptions to external, objective reality—the kinds of things a camera can film.” Here, says Eisner, is one student’s brief but powerful submission: “She rides in the passenger seat of a dark sedan, her hands tightly clutching the perfectly folded American flag.”

I’m reluctant to single out favorite chapters, but I truly enjoyed my buddy Karl Iglesias’s savvy suggestions about writing great dialogue. (As he notes, you should never underestimate the power of silence.) And Deborah Dean Davis’s blunt and funny essay on how to launch and sustain a screenwriting career is a hoot. (She gives clothing advice, marital advice, and suggestions about how the power of chutzpah can help you navigate the winding byways of Tinseltown.)

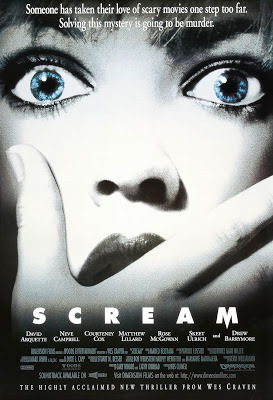

Will all this good advice change your life? Hard to say – but screenwriters from Earl W. Wallace (Witness) to Kevin Williamson (Scream) to Melissa Rosenberg (Twilight) have the UCLA Extension Writers’ Program to thank for jumpstarting their stellar Hollywood careers.

Aspiring writers might enjoy my talk at the San Fernando Valley branch of the California Writers Club this coming Saturday, November 2. Here’s the complete info.

Published on October 29, 2013 10:05

October 25, 2013

Kids from Brooklyn: Danny (Kaye) and Sylvia (Fine) and Woody (Allen) and Spike (Lee)

It must be something in the water. Over the years, the number of talented people coming out of New York’s most populous borough has been staggeringly high. I recently toured the picturesque section called Brooklyn Heights, strolling through the neighborhood where Arthur Miller wrote Death of a Salesman, Thomas Wolfe struggled with Look Homeward, Angel, and Betty Smith explored domestic life in the popular novel, A Tree Grows in Brooklyn. Ironically, they all wrote about misery while living with a view of the New York skyline that’s downright gorgeous.

Though newly home, I’m still in a New York state of mind. A young man I know and love is a budding writer of music theatre. A showcase of his original work -- Dorks, Drunks, and Dinosaurs: The Songs of Jeff Bienstock – just lit up the stage of a small but trendy cabaret theatre. The Laurie Beechman is on fabled 42nd Street, a few blocks west of Broadway. Jeff, though, does not call Manhattan home. One of his catchiest songs, “California Time,” may be a paean to his native Santa Monica. But, like so many young folks with creative aspirations, he’s turned into a Brooklynite.

Appropriately, I’ve just seen a small exhibit housed in the Walt Disney Concert Hall in downtown Los Angeles. Called “Two Kids from Brooklyn,” it pays tribute to the careers of Danny Kaye and Sylvia Fine. It’s accompanied by clips of Kaye in some of his many guises: clowning in films and on television, conducting the New York Philharmonic, serving as UNICEF ambassador to needy children around the globe. Kaye may have become a citizen of the world, but he started out in Brooklyn. And like so many entertainers of the day, he began by performing as a “tummler” (or comic master-of-ceremonies) in Borscht Belt summer resorts. That’s where he met another kid from Brooklyn, Sylvia Fine, who had a talent for writing witty songs. One of these, featuring a pseudo-French hat-maker called Anatole of Paris, was debuted by Kaye at Camp Tamiment in the Poconos. He later used it as the finale of his nightclub act, and in 1947 it became a dream sequence in The Secret Life of Walter Mitty. Obviously, Sylvia Fine was a great help to Danny Kaye’s career. As she often put it, “He couldn’t afford to pay me so he married me.”

A later kid from Brooklyn, Woody Allen, didn’t hone his comic talents in the Catskills. Rather, while still in his teens, he was earning big bucks for supplying TV performers with material. His involvement with Sid Caesar put him in the company of some of the best comic writers in the business. By the Sixties, he was performing his own material, then went on to write, direct, and star in some of our best-loved films. His portraits of Jewish homelife in Brooklyn are iconic – I’ll never forget Alvy Singer’s family living under the roller coaster in Annie Hall – but Allen himself eventually moved to a two-story penthouse on Manhattan’s Upper East Side.

Spike Lee has devoted much of his directing career to films with an unmistakable Brooklyn flavor. The gritty neighborhood of Bedford-Stuyvesant has always been his particular territory, starting with his NYU thesis film, Joe's Bed-Stuy Barbershop: We Cut Heads . Later Lee portraits of the area include the impish She’s Gotta Have It and the dark, disturbing Do The Right Thing.

In Saturday Night Fever, John Travolta’s character finally makes it out of Brooklyn to start a better life in Manhattan. Today’s Brooklynites prefer to stay put, but I hope some of them make it to Broadway.

Published on October 25, 2013 10:11

October 22, 2013

Fathers and Sons: The Pickle Family Lives On

Ever hear of the Pickle Family Circus? It was a purebred Northern California creation from the 1970s, evolving out of the satirical San Francisco Mime Troupe and adding a whole lot of juggling. One of the Pickles was Bill Irwin, who later clowned on Broadway in Fool Moon and then won a Tony for a deadly serious role in the 2005 revival of Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? (On film, he was the dad in Jonathan Demme’s Rachel Getting Married; children know him as Mr. Noodle from Sesame Street.)

I knew about Bill Irwin. But not until I saw Humor Abuse at L.A.’s Mark Taper Forum did I ever heard of Larry Pisoni. Humor Abuse is a fascinating one-man show in which Larry’s son, Lorenzo Pisoni, grapples with his father’s legacy. Lorenzo’s parents, Larry and Peggy, were Pickle Family founders. From a very young age, their young son was incorporated into the show, performing intricate and sometimes dangerous clowning routines. Lorenzo loved circus life, but winning favor from his hard-to-please father was sometimes tough. It was only in later years that Lorenzo came to realize the scope of Larry’s personal failings, and the extent to which they kept his dad from having a happy life.

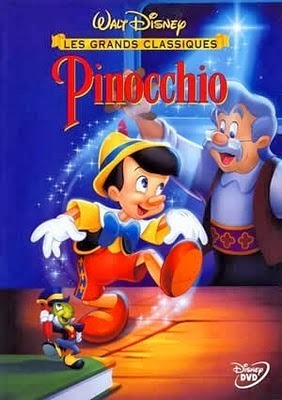

An important point comes out late in the show: when a baby boy was born to the senior Pisonis, Larry gave Peggy two name choices for the new arrival: Lorenzo or Geppetto. As it happened, Larry’s own clown name was Lorenzo Pickle. And when pint-sized Lorenzo was old enough to perform, he joined his father for a Pinocchio routine, in which the spotlight was on Larry in the Geppetto role. So, whichever name Peggy had chosen, she would have been naming her new son after his dad’s alter ego. Poignantly, when his circus years were long gone, Larry started introducing himself socially as Lorenzo. The real Lorenzo, of course, was disquieted by this borrowing of his personal nomenclature. So a play that’s chockfull of fun and games turns out, after all, to be an exploration of identity, and what it means to be a father’s son.

Seeing Humor Abuse made me realize how many father-and-son pairs exist in Hollywood. Some have been mutually supportive. (See, happily, Tom and Colin Hanks.) Others have had relationships that are fraught with tension. Peter Fonda, always at odds with his famous father Henry, consistently chose roles that the older Fonda would have found offensive. Just try imagining what the heroically all-American Henry Fonda, who’d starred as Abe Lincoln and Tom Joad, would have thought of his son’s renegade biker roles in The Wild Angels and Easy Rider. Many’s the Hollywood son who has never managed to live up to his father’s level of accomplishment and acclaim. (I’m thinking of Patrick Wayne, who was given forgettable roles in his father’s The Searchers, The Alamo, and The Green Berets.) But it also can be awkward when a son far surpasses his father’s screen achievements. Harry Hoffman, father of Dustin, was once a set decorator for Columbia Pictures. When a scene in The Graduate was being shot in the lobby of L.A.’s Ambassador Hotel, Harry was invited to watch. As Dustin, in his first big movie role, cringed with embarrassment, his dad tried to get involved, offering his advice on the filmmaking process to anyone who’d listen.

Rance Howard was and is a working actor, one of those familiar faces that pop up in small roles in big films. His son Ron became a celebrity at age 5. More later about their very special relationship. (Maybe I’ll save it for Fathers’ Day.)

Published on October 22, 2013 09:30

October 17, 2013

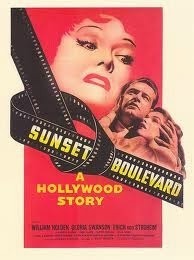

Sunset Boulevard: The Street Where Dreams Are Born

In the film version of Elmore Leonard’s Get Shorty, schlockmeister Harry Zimm (known for his direction of the Slime trilogy) has a second-floor office on the Sunset Strip. Just overhead looms an enormous billboard featuring Angelyne, the buxom, bubble-headed blonde who for years epitomized somebody’s idea of Hollywood glamour.

Angelyne and the Sunset Strip just seem to go together. The perennial starlet and the winding thoroughfare that abuts the Hollywood Hills: both represent the triumph of style over substance. Billy Wilder’s Sunset Boulevard is set west of the Strip, in that tony stretch of Beverly Hills where stars (and oil sheiks) have built opulent mansions. But as you drive east across the Beverly Hills border into West Hollywood, Sunset becomes a place of entertainment and commerce. Sidewalk cafés. Boutiques. Liquor stores. The Whisky a Go Go, where the Doors used to be the house band. The Roxy, where I saw Tim Curry in the U.S. debut of a stage musical called The Rocky Horror Show. The Viper Room, where River Phoenix died.

Some associate the Sunset Strip with a hit TV show about private eyes. But for me the Strip has always meant Roger Corman. In the course of his long career, Roger was several times headquartered on Sunset, and he often told me how much he enjoyed that locale. His very first office was over a quasi-British pub called The Cock ‘n’ Bull. In the Sixties, while shooting The Trip, he captured the swirl of night-time activity without permits, by seating his cameraman in a wheelchair and having him pushed through the throngs of young hippies who then crowded the Strip’s narrow sidewalks

When I first came to work for Roger at New World Pictures, we were housed in a shabby penthouse suite at 8831 Sunset, reached by a rather sexy glass elevator. Tawdry movie posters hung everywhere (“It’s Always Harder at Night . . . for the Night Call Nurses”), except in Roger’s own office. On his walls, he favored large placards that had been given to him by a French producer after the 1968 student revolts in Paris. They were emblazoned with revolutionary slogans like «Salaires Légères, Chars Lourds»(“Light Salaries, Heavy Tanks”) and «Le Patron a Besoin de Toi, Tu n’as pas Besoin de Lui» (“The Boss Needs You, You Don’t Need the Boss”). These sentiments may have been fitting when Roger took on the Establishment with The Wild Angels, but they seemed curiously out of place as décor for a rising film producer known for his skinflint ways.

If we New World folk ventured out at lunchtime, we could cruise the aisles of the wonderful Tower Records, or eat sandwiches in a dim booth at the Ramada Inn coffee shop next door. I often brought a bag lunch, but there was no good place to eat it. So I’d wander the Strip, sometimes venturing into one of the posh residential enclaves just to the north. That’s where a man in a long white Bentley tried to pick me up, claiming there was a party at Robert Wagner’s place. No telling what might have happened if I’d gone along for the ride.

One thing that didn’t exist on the Strip in the early 1970s was a good place to buy books. Now, happily, there’s Book Soup, one of those classic independent bookstores that stoke the literary imaginations of serious readers. Right now, copies of my insider biography, Roger Corman: Blood-Sucking Vampires, Flesh-Eating Cockroaches, and Driller Killers, are sitting on a Book Soup shelf, waiting for customers to give them a good home. Enough said.

Published on October 17, 2013 09:31

October 15, 2013

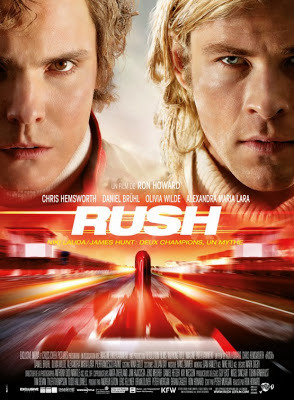

"Rush": Capturing the Need for Speed

I didn’t rush out to see Rushwhen it was newly released. Movies about Formula One auto racing are not my idea of summer fun. I’m a veteran of L.A.’s mean streets and meaner freeways, which means I consider driving a chore, not an art form. Still, as Ron Howard’s biographer, I felt obligated to look in on his latest project. And so, because I suspected that Rush deserved to be seen on the big screen, I headed for a matinee at the trendy Landmark Theater complex in West L.A. I curled up on a comfy leather couch in the Landmark’s “screening lounge” – and found myself mesmerized by this real-life tale of two drivers who found very different ways of getting to the finish line.

Ron Howard, of course, made his directorial debut with a race car movie. That was back in 1977, when the 23-year-old Howard persuaded Roger Corman (who else?) to let him follow up a starring role in Eat My Dust with another teen car-crash comedy called Grand Theft Auto. He co-wrote the script with his father Rance, played the male lead, and brought in the movie on time and on budget. Given that he was allotted a mere $602,000 and a shooting schedule of only 23 days, speed and efficiency were crucial. Howard remains proud of having broken the previous New World Pictures record by achieving ninety-one camera set-ups in a single day.

Obviously, Rush cost much more and took much longer to shoot. But the economy of means that Howard learned from his Corman days obviously helped shape this complex film. Its script, by the talented Peter Morgan, is strong, as are the performances of the two lead actors, Daniel Brühl (as Austria’s Niki Lauda) and Chris Hemsworth (as British bad-boy James Hunt). Yet I consider it above all a triumph of cinematography and editing. The impressionistic camerawork of Anthony Dod Mantle (known for Slumdog Millionaire and 127 Hours) puts the viewer in the driver’s seat, and Howard’s longtime editors Dan Hanley and Mike Hill seamlessly intercut the cheering throngs, the rain-soaked tracks, the pulsing pitons of the world’s fastest cars to get me caught up in the action. Normally when it comes to the finer points of auto mechanics, I don’t go beyond listening to Car Talk, and yet I could easily follow the story’s technical twists and turns. And, though I had some inkling of what was coming, I was gripped with anticipation.

Which for me made Rush the antithesis of Gravity. That film was quiet, set against empty spaces. This one is packed with people, places, noise. Yet they’re both, in their way, about survival. For me, anyway, Rush was the one that had me on the edge of my seat.

Given what I know of Ron Howard, I believe he can strongly identify with Lauda, the methodical pragmatist who badly wanted to win, but also wanted to live to race another day. Yet I also believe Howard is dazzled (as Lauda apparently was) by the glamorous, devil-may-care James Hunt. The tension between these two very different champions, on the track and off, is part of what makes Rush so thrilling. But champions also need teams behind them, just as Howard has relied throughout his career on a loyal production team that rarely changes. Howard’s skill as a team leader is part of why he has Hollywood’s respect, and mine too.

I must confess, when I headed out of the parking garage and into a sunny L.A. afternoon, that I was tempted to put a little extra vroom-vroom into my drive home.

Published on October 15, 2013 09:29

October 11, 2013

Get Elmore: An Unlikely Fan’s Valentine to Tinseltown

Elmore Leonard, I hardly knew you. Years ago, when I was reviewing movies, I panned a grim little melodrama called The Big Bounce. It featured an “it” couple of that era – Ryan O’Neal and Leigh Taylor-Young – and there was nothing much to like. I didn’t know then that The Big Bounce was adapted from an Elmore Leonard crime novel, and he hated its screen transformation even more than the critics did.

When Leonard passed on in August 2013, many obits focused on his testy relationship with Hollywood. But his tough, funny stories about crooks, con men, and connivers led to a few good films too. In his honor, I watched Jackie Brown, which put Quentin Tarantino’s personal spin on Leonard’s Rum Punch, while giving Pam Grier one of her best roles as a flight attendant negotiating her way through a thicket of bad guys. Jackie Brown is a quintessentially L.A. story, making creative use of LAX and (of all places) the soulless Del Amo shopping mall. Then I finally sat down to read Leonard first-hand. My choice was Get Shorty, a gritty and hilarious tale of a Brooklyn mobster who comes to LaLa Land and discovers it’s not all that different from the world he left behind.

Get Shorty is Leonard’s wry tribute to the dreamers and shysters who populate Hollywood. The joke is that his hero, Chili Palmer, is smart enough and cool enough to progress in what seems like record time from debt-collector to movie producer. Along the way, he tries on many different Hollywood hats: actor, director, writer. This gives Leonard the chance to mock the status of screenwriters within the motion picture industry: “You have the idea and you put down what you want to say. Then you get somebody to add in the commas and shit where they belong, if you aren’t positive yourself. Maybe fix up the spelling where you have some tricky words . . . . You come to the last page you write in ‘Fade out’ and that’s the end, you’re done.” Ultimately, Leonard knows (as all Hollywood folks know) that it’s a crap shoot: “The movie business, you can do any fuckin thing you want ‘cause there’s nobody in charge.”

The movie version of Get Shorty, directed with tongue-in-cheek panache by Barry Sonnenfeld, features John Travolta as Chili, Gene Hackman as B-movie maven Harry Zimm (known for lensing the Slime Creatures trilogy), and Danny De Vito as a cocky (but very short) movie star who loves waxing eloquent about the mysteries of his craft. Two of the featured players are, alas, no longer with us: Dennis Farina as a hard-luck thug and James Gandolfini (with a beard and a surprising cornpone accent) as a stuntman-turned-enforcer. Rene Russo is the scream queen who’s much smarter than she looks, and Delroy Lindo is menacing but funny as a slick operator who feels Chili’s horning in on his territory.

I love Get Shorty’s affectionate grasp of L.A. geography. There’s a fondness for honest-to-god Hollywood stars too: Bette Midler, Penny Marshall, and Harvey Keitel pop up in memorable cameos. And for me the thread that runs through the whole complicated story is Chili’s genuine love of movies as an art form. At one point, he ducks into Santa Monica’s vintage Aero Theater to watch Orson Welles’ 1958 classic, Touch of Evil, in which Charlton Heston (of all people) plays a Mexican narcotics officer taking on a corrupt cop. Chili knows all the lines by heart. He’s a fan, in his way, and I think Elmore Leonard was too.

Published on October 11, 2013 11:20

October 8, 2013

"Gravity": In Space No One Can Hear You Yawn?

Don’t get me wrong: Gravity is an impressive achievement. In filming a saga of astronauts stranded in space, Alfonso Cuarón (hailed for such distinctive work as Children of Men and Y Tu Mamá También) has artfully used all the cinematic tools that today’s Hollywood has to offer. Since I can’t wrap my brain around technology, I can only marvel at Cuarón’s creative use of CGI and other tricks to show Sandra Bullock and George Clooney navigating weightlessly through Zero-G. And the realistic views of the sun rising over the rim of our own planet are staggeringly gorgeous.

Why then, didn’t I feel moved as well as impressed?

We human beings have always been fascinated by the idea of space travel. Georges Méliès, back in 1902, filmed the fanciful voyage of some scantily dressed cuties, whose rocket ship hits the Man in the Moon smack in the eye. By the Sixties, when the space race between the US and the USSR had heated up for real, Hollywood couldn’t get enough of astronaut movies. Roger Corman’s War of the Satellites tried for a thriller involving space aliens, and Don Knotts, in The Reluctant Astronaut, played the challenges of weightlessness for laughs. But none of this prepared Sixties audiences for 2001: A Space Odyssey, with its mind-blowing view of a future in which space travel is routine and computerized technology is a way of life. Fans are still arguing about the film’s meaning, but its visual portrait of life in space is still aesthetically unforgettable. Then a decade later came Alien, which discovered that a spaceship full of astronauts was a rip-roaring backdrop for a monster flick.

Alien found suspense by picking off its characters one by one, until we were down to the gutsiest of “final girls,” Sigourney Weaver’s Ripley. By contrast, the suspense in Gravity is of a less gimmicky sort: we are asked to invest our emotions in the fate of someone who may or may not have the guts, stamina, and ingenuity to survive a life-or-death situation. This is hardly unique in the annals of Hollywood. Think Cast Away, 127 Hours, The Life of Pi, and Robert Redford’s upcoming All is Lost. I found Sandra Bullock’s plight gripping, but never enough to make me forget that it’s only a movie. The reviewers who’ve commented on the B-movie aspects of Gravity’s plot are quite right. There’s the relationship between the grizzled veteran and the green-around-the-gills rookie, along with a cascade of unfolding disasters, and (of course) the eye candy of Bullock facing death in her skivvies.

I’m married to an aerospace engineer who once seriously hoped to join the astronaut corps. And I myself, as a U.S. Pavilion guide at Osaka’s Expo 70 just one year after the first moon landing, quickly learned to respect the challenges of space exploration. I well remember suffering, along with everyone else, when the astronauts of Apollo 13 seemed to be lost in space for real. Ron Howard’s 1995 movie version of that apparently doomed mission had me breathless with suspense, even though the outcome was well known. I cared more in Apollo 13 than in Gravity because Howard’s characters seemed more complete. I knew all they were risking in human terms, and I desperately wanted to see families reunited and lives on earth continue onward.

Which doesn’t detract from Gravity’s accomplishment as a darned good technothriller. The engineers I know have given high praise to its grasp of space science. And for me it’s accomplished something else: now my husband doesn’t yearn to be an astronaut anymore.

Published on October 08, 2013 09:37

Gravity: In Space No One Can Hear You Yawn?

Don’t get me wrong: Gravity is an impressive achievement. In filming a saga of astronauts stranded in space, Alfonso Cuarón (hailed for such distinctive work as Children of Men and Y Tu Mamá También) has artfully used all the cinematic tools that today’s Hollywood has to offer. Since I can’t wrap my brain around technology, I can only marvel at Cuarón’s creative use of CGI and other tricks to show Sandra Bullock and George Clooney navigating weightlessly through Zero-G. And the realistic views of the sun rising over the rim of our own planet are staggeringly gorgeous.

Why then, didn’t I feel moved as well as impressed?

We human beings have always been fascinated by the idea of space travel. Georges Méliès, back in 1902, filmed the fanciful voyage of some scantily dressed cuties, whose rocket ship hits the Man in the Moon smack in the eye. By the Sixties, when the space race between the US and the USSR had heated up for real, Hollywood couldn’t get enough of astronaut movies. Roger Corman’s War of the Satellites tried for a thriller involving space aliens, and Don Knotts, in The Reluctant Astronaut, played the challenges of weightlessness for laughs. But none of this prepared Sixties audiences for 2001: A Space Odyssey, with its mind-blowing view of a future in which space travel is routine and computerized technology is a way of life. Fans are still arguing about the film’s meaning, but its visual portrait of life in space is still aesthetically unforgettable. Then a decade later came Alien, which discovered that a spaceship full of astronauts was a rip-roaring backdrop for a monster flick.

Alien found suspense by picking off its characters one by one, until we were down to the gutsiest of “final girls,” Sigourney Weaver’s Ripley. By contrast, the suspense in Gravity is of a less gimmicky sort: we are asked to invest our emotions in the fate of someone who may or may not have the guts, stamina, and ingenuity to survive a life-or-death situation. This is hardly unique in the annals of Hollywood. Think Cast Away, 127 Hours, The Life of Pi, and Robert Redford’s upcoming All is Lost. I found Sandra Bullock’s plight gripping, but never enough to make me forget that it’s only a movie. The reviewers who’ve commented on the B-movie aspects of Gravity’s plot are quite right. There’s the relationship between the grizzled veteran and the green-around-the-gills rookie, along with a cascade of unfolding disasters, and (of course) the eye candy of Bullock facing death in her skivvies.

I’m married to an aerospace engineer who once seriously hoped to join the astronaut corps. And I myself, as a U.S. Pavilion guide at Osaka’s Expo 70 just one year after the first moon landing, quickly learned to respect the challenges of space exploration. I well remember suffering, along with everyone else, when the astronauts of Apollo 13 seemed to be lost in space for real. Ron Howard’s 1995 movie version of that apparently doomed mission had me breathless with suspense, even though the outcome was well known. I cared more in Apollo 13 than in Gravity because Howard’s characters seemed more complete. I knew all they were risking in human terms, and I desperately wanted to see families reunited and lives on earth continue onward.

Which doesn’t detract from Gravity’s accomplishment as a darned good technothriller. The engineers I know have given high praise to its grasp of space science. And for me it’s accomplished something else: now my husband doesn’t yearn to be an astronaut anymore.

Published on October 08, 2013 09:37

Beverly in Movieland

I write twice weekly, covering topics relating to movies, moviemaking, and growing up Hollywood-adjacent. I believe that movies can change lives, and I'm always happy to hear from readers who'd like t

I write twice weekly, covering topics relating to movies, moviemaking, and growing up Hollywood-adjacent. I believe that movies can change lives, and I'm always happy to hear from readers who'd like to discuss that point.

...more

- Beverly Gray's profile

- 10 followers