Beverly Gray's Blog: Beverly in Movieland, page 122

March 25, 2014

“I Talk the Line”: Johnny Cash Discovers Acting

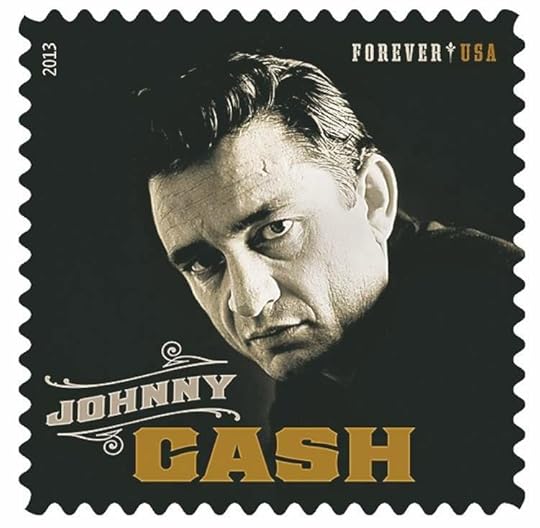

So a newly rediscovered album by the great Johnny Cash goes on sale today. Out Among the Stars , recorded in the early 1980s when Cash had a deal with Columbia Records, was shelved because the label deemed it non-commercial, even though it featured Cash at the height of his powers, along with wife June Carter and good friend Waylon Jennings. The old tapes have been resurrected by Cash’s son, John Carter Cash, and now the public has the chance to listen in. This album, along with a very dramatic Johnny Cash postage stamp and a bestselling biography by veteran music writer Robert Hilburn, signals a new groundswell of interest in the Man in Black.

Hollywood has long been aware of Johnny Cash, who died in 2003. The 2005 biopic Walk the Line nabbed a Best Actor Oscar nomination for Joaquin Phoenix and a Best Actress win for Reese Witherspoon, who put on a black wig to play the everlovin’, autoharp-strummin’ June Carter. Cash’s deep, mournful baritone was featured on many movie soundtracks, and over the years he acted in numerous TV episodes, especially in western roles. Playing himself, he guest-starred on everything from Hee Haw to Saturday Night Live, and even hosted his own musical variety show (1969-1971)

Early in his career, Cash was eager to emulate Elvis Presley, who had capitalized on his recording success by starring in a long string of movies. The first, Love Me Tender, appeared in 1956: this romantic melodrama set just after the Civil War earned Elvis some respect as an actor while also launching a mega-hit record. Thereafter, Elvis made scores of movies (of varying quality) while the money kept rolling in.

Cash’s own feature film debut, following a few appearances on shows like Wagon Train and The Rebel, was the leading role in a low-budget 1961 thriller called Five Minutes to Live. I discovered it when I was researching the life of Ron Howard. At age seven, not long after he began playing Opie on The Andy Griffith Show, Ronny was cast as Bobby Wilson, a small-town boy whose mother is the film’s female lead. Normally Rance and Jean Howard were cautious indeed about selecting material for their talented young son. So it’s surprising to come upon Five Minutes to Live (later retitled Door to Door Maniac). Whereas Elvis’s movie roles, from the first, always put him in a good light, Johnny Cash seemed to be trying for a darker sort of appeal. In Five Minutes to Live, he’s a hardened criminal in on a nefarious plot to hold a rich man’s wife for ransom. He’s sadistic, as well as sexually predatory. But then young Bobby comes home from school, upsetting all the calculations of Johnny and his partner in crime. And soon the police get wind of what’s going on.

The ending involves serious gunplay, major jeopardy for young Bobby, and an illogically rosy fadeout. (The contradictions and plot holes in the clumsy script defy description.) Though Johnny Cash is definitely pegged as the bad guy, he gets a moment of redemption when he takes pity on the endangered young boy. He also gets to sing. He first gains access to his victim’s house by posing as a door-to-door guitar instructor. Later he uses his instrument to serenade the captive wife with a charming ditty about how she has (yup!) only five minutes to live unless someone shows up with the loot.

Cash, not surprisingly, makes a powerful movie villain. I doubt this film, though, contributed much of value to his remarkable career.

Published on March 25, 2014 12:24

March 21, 2014

Replaceable You: Saying Goodbye to One and a Half Men

The hit CBS sitcom Two and a Half Men has been with us (God help us!) for more than a decade. Originally it was a raunchy odd-couple story about an uptight chiropractor (Jon Cryer) who got divorced and moved into the swinging Malibu beach pad of his jingle-writing brother (Charlie Sheen). The twist was that Cryer brought a young son (Angus T. Jones) to the relationship. Hence the series’ title. As the whole world knows by now, Sheen flipped out in early 2011, making nasty statements about series creator Chuck Lorre, and earning himself a million headlines, a trip to rehab, and a pink slip.

But a hit is a hit, and so Lorre and company opened season nine by orchestrating a colorful off-camera death for Sheen’s character and providing Cryer with a new roommate, played by Ashton Kutcher. The show’s popularity continued. Still, all was not well in CBS-land. Young Angus T. Jones had debuted on the show at age 10. By age 17, he’d become the highest paid child star in television, earning $7.8 million over the course of two seasons. Then in 2012 came his loud (OK, strident) pronouncement that he’d found God. The new God-fearing Jones decried Two and a Half Men as “filth,” labeled himself a “paid hypocrite” for his role in it, and warned audiences not to watch. It’s obvious what had to happen next. Jones’ character joined the U.S. Army and vanished into the distance.

Wait! – wasn’t that pretty much what happened to Richie Cunningham when Ron Howard decided to leave Happy Days? Except, of course, that Richie was sent to Greenland, not Japan, and returned for the occasional Very Special Episode.

In any case, Two and a Half Men now has a new member of the younger generation. She’s Amber Tamblyn, playing a previous unacknowledged daughter of the Charlie Sheen character. And she’s a lesbian. Does that make her a half man, perhaps?

Creators of hit series are well aware that the actors playing popular characters may not want to stick around forever. But it takes some ingenuity to figure out what to do. The family sitcom My Three Sons faced a stumbling block when eldest son Tim Considine left the series. Solution: #2 son Don Grady was moved up to #1, and dad Fred MacMurray adopted a younger boy to give him the requisite number of offspring.

Then there was M*A*S*H, both an hilarious comedy and a serious meditation on the perils of warfare. The show, set in a medical unit during the Korean War, was on the air so long (1973-1983) that personnel changes were inevitable. Still, those in charge worked hard to maintain the interpersonal dynamics that made the series a hit. In the early days, the tent-mate and nemesis of Hawkeye Pierce (Alan Alda) was Larry Linville’s incompetent Captain Frank Burns. When Linville moved on, he was replaced by David Ogden Stiers’ Major Charles Winchester, which made Hawkeye’s chief antagonist no longer a nincompoop but rather a highly intelligent snob. Another important cast change came when McLean Stevenson chose to no longer play the local commander, goofy Lt. Colonel Henry Blake. His replacement, down-to-earth Henry Morgan, more than adequately filled the bill. But fans of the show will never forget Stevenson’s final episode. Through most of it was filled with pranks and warm goodbyes, the tag ending startled viewers (and cast members, I’m told) with the news that Henry Blake’s transport plane had been shot down over the Sea of Japan, and that there were no survivors. That’s one way to ensure there’ll be no return visits.

Published on March 21, 2014 11:43

March 18, 2014

Grand Illusions at the Grand Budapest Hotel

Airplanes are disappearing from our skies. Sovereign nations are splitting in two. The weather continues to be weird, and the other morning I was shaken and stirred by a 4.4 earthquake. No wonder we moviegoers are feeling nostalgic about the past.

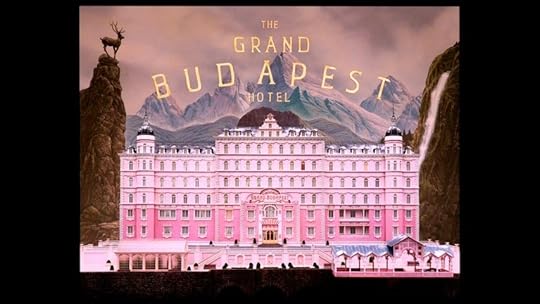

Which perhaps is part of the appeal of Wes Anderson’s The Grand Budapest Hotel. An elderly relative of mine jumped to the conclusion that this new film was a reworking of Grand Hotel. That 1932 ensemble classic (based on a bestselling novel) was set in a luxurious Berlin hostelry; it featured such MGM superstars as John Barrymore as a dissolute aristocrat, Greta Garbo as an aging ballerina, Lionel Barrymore as a dying accountant, and Joan Crawford as an ambitious stenographer. New York’s Waldorf-Astoria is still proud of the fact that a remake-of-sorts, Week-End at the Waldorf, was filmed on its premises in 1945. Eventually Neil Simon was to use a similar premise – that of criss-crossing lives in a sumptuous public place—for his Plaza Suite and California Suite comedies. Grand Hotel, by whatever name, reinforces our sense of hotels as romantic venues where a wide array of folk come together and drift apart.

It’s certainly true that the always inventive Wes Anderson is playing upon these assumptions. His grand hotel, set in the fictional Mittel-European Republic of Zubrowka, is a pink wedding cake of a place. In the 1930s, when most of the film is set, its lobby is filled with the powerful, the wealthy, and the beautiful, all of them nibbling exquisite pastries that arrive daily in cunning little pink boxes tied with ribbons. Elegantly presiding over the scene is Monsieur Gustav H., conciergeextraordinaire, who is viewed with awe by Zero Mustafa, lowly lobby boy and immigrant from somewhere in the murky Middle East. Although the adventures of Zero and Monsieur Gustav eventually involve murder, theft, and incarceration, we can be forgiven for seeing their life-or-death escapades through Anderson’s dreamy haze, which encompasses the Grand Budapest Hotel and everyone who enters its portals.

Wes Anderson has made films about insular clans before. I’m thinking particularly of The Royal Tenenbaums, where the eccentric members of one extended family were on vivid display. I found that film clever, but ultimately unsatisfying. Who cared, after all was said and done, about all those wealthy, talented, discontented people, even if they were played by interesting, quirky personalities like Gene Hackman, Anjelica Houston, Ben Stiller, and Owen Wilson?

What’s special about The Grand Budapest Hotel is the way it sets its tight little world against the forces of history. Though the film’s style of framing and pacing makes it consistently hilarious, reality keeps intruding in subtle ways. Like Zero’s offhand reference to the fact that back in his home country he was tortured, and his father assassinated, in the course of some nameless little war. And the creeping forces of Fascism that keep rearing their ugly heads each time our heroes board a train. By the time we’ve finished with the central story line, the movie has shifted to black and white, and the charming, carefree old ways are gone forever.

But we’re not allowed to be sad. Those stalwart souls who stick around for the whole of the long, lo-o-o-ng credit roll will be treated to some cheery balalaika music, accompanying an odd little dancing figure who dispels any sort of gloom. And with such familiar faces as Bill Murray, Edward Norton, Bob Balaban, and Harvey Keitel popping up at odd moments, life in Wes Anderson’s world truly feels like a cabaret.

It’s a treat to study the website of this film, which includes a link to the purely hypothetical Zubrowka Film Commission. Zubrowka, we are told, “offers a grand destination featuring a film-friendly community, luxurious locations, and free production space.”

Published on March 18, 2014 11:36

March 14, 2014

Musings from the Mojave: Ridgecrest, Lone Pine, and Manzanar

Ever hear of Ridgecrest? It’s a small, friendly town in the Upper Mojave Desert, 2 ½ hours and a world away from Los Angeles. Still, Ridgecrest is glad to be considered an outpost of Movieland.

Last week I spent several days in Ridgecrest, as guest of the East Sierra Branch of the California Writers Club. The pleasant, attentive people to whom I spoke – many of them authors themselves – seemed fascinated by my stories about what it took to write, publish, and promote my Roger Corman: Blood-Sucking Vampires, Flesh-Eating Cockroaches, and Driller Killers. Ridge Writers, as they call themselves, have had their share of Hollywood experiences. Among the movies filmed in their desert community are Jurassic Park, Holes, Tremors, and Land of the Lost.

Up the road a piece from Ridgecrest is Lone Pine, population 2,035. It’s at a higher elevation than Ridgecrest (3,727 feet, to be exact), and its location – nestled against the rugged Alabama Hills, which abut the eastern slope of the Sierra Nevadas – makes it particularly picturesque. Which means, of course, that Hollywood discovered it long ago. Since the days of silent movies, Lone Pine has been the location of choice for shooting cowboy movies. Every he-man from Gary Cooper to Clark Gable to Humphrey Bogart has strapped on his six-guns in this vicinity. It’s also been the locale where Roy Rogers and William “Hopalong Cassidy” Boyd filmed most of their western adventures, and where the Lone Ranger roamed, with the faithful Tonto in tow.

Which is why Lone Pine boasts a dandy little attraction. Avid collectors Beverly and Jim Rogers display their collection of western memorabilia in Lone Pine’s Film History Museum, which bills itself as the place “where the real west becomes the reel west.” Visitors generally start out watching a short documentary, which reveals that in the days before overseas location shooting, the region also supplied exotic desert terrain for Gunga Din and The Lives of a Bengal Lancer. But the doc’s real focus, of course, is on westerns, and we learn that the town’s citizenry often helped out by supplying horses and props. At the fadeout, we hear the Statler Brothers singing their ode to a vanishing breed, “Whatever Happened to Randolph Scott?”

Among the museum’s treasures are a case devoted to movie bad guys and a fascinating assortment of gear worn by the late stuntman Richard Farnsworth. (You can see a protective vest made for a guy who’s stuck being struck by an arrow, and another used by someone who needs to be dragged by a galloping horse.) The eldest of Roy Rogers’ nine children has contributed a slide show of family photos. Though the autographed celebrity headshots on the walls of the town’s best restaurant are mostly quite dated (Dale Evans, Ernest Borgnine, Sally Struthers), I also discovered that as a filming location Lone Pine has not yet gone out of style. Bits of Iron Man were shot here, along with Gladiator and Star Wars. Only two years ago, Quentin Tarantino brought some of his cast to Lone Pine for Django Unchained.

But to me the most remarkable location is to be found a few miles further north. Manzanar was once a “relocation” camp where 11,000 Japanese Americans were incarcerated by their own government from 1942 to 1945. Today, it’s being preserved as a national monument. For visitors it’s an eerie place, especially at sunset, when the wind blows lonesome and the old Japanese cemetery stands out starkly against the Sierras. Lest we forget the cruelties of which we as a people are capable, someone really needs to make a great movie.

Published on March 14, 2014 10:27

March 11, 2014

Saving Mr. Disney (and Mr. Corman)

The word “frozen” reminds today’s movie fans of a blockbuster family film, the first from Walt Disney Animation Studios to ever win an Oscar for best animated feature. Ironically, it also suggests a longstanding rumor about Disney himself. Here’s how Neal Gabler opens his 2006 biography, Walt Disney: The Triumph of the American Imagination -- “He was frozen. At least that was the rumor that emerged shortly after his death and quickly became legend: Walt Disney had been cryogenically preserved, hibernating like Snow White and Sleeping Beauty, to await the day when science could revive him and cure his disease.”

In truth Disney, who died of lung cancer in 1966 at the age of 65, was cremated, and his remains interred at Glendale’s Forest Lawn. But Gabler’s most memorable revelations are about the young Walt Disney, who was a far cry from the jolly Uncle Walt we Baby Boomers remember. As a youthful cartoonist, Disney was wildly ambitious, desperate to overcome childhood deprivation by using his drawing pencil to make his mark on the world. Gabler explains, “For a young man who had chafed within the stern, moralistic, anhedonic world of his father, animation provided escape, and for someone who had always been subjugated by that father, it provided absolute control. In animation Walt Disney had a world of his own.”

But such was Walt’s fundamental restlessness that he could never be satisfied with a single category of achievement. That’s why the Mickey Mouse short subjects led to the feature-length Snow White, which led to the experimental Fantasia, to live-action features, and wild-life documentaries. Veteran Disney animator Milt Kahl put it this way: “He was interested in a picture until he had all the problems solved and then he just lost interest.” At times, Walt turned away from movies altogether, devoting all his energies to the creation of Disneyland, and then to the concept of a gargantuan utopian community that became Walt Disney World. At the end of his life, his dream of founding a City of Arts evolved into a unique interdisciplinary university, today’s CalArts.

I never met Walt Disney. But in reading Gabler’s portrait of him, I couldn’t help recalling a restless figure who loomed large in my own life, B-movie legend Roger Corman. Obviously they are known for very different kinds of entertainment: Roger is famous for lurid monster movies, not wholesome family fare. And Disney’s artistic perfectionism would not suit a man who could happily grind out 20 low-budget quickies in a single year. Still, Roger as producer is very much like Disney in his prime, a superb storyteller who may not have been hands-on in the daily running of his company, but whose “sensibilities governed everything the studio produced.” A point that former Disney staffers sometimes made – “he’s a genius at using someone else’s genius” – is one that fits Roger as well. And the comment of one Disney underling that “you’d do anything for a smile, even though the next day you might be fired” certainly applies.

Gabler also emphasizes Walt Disney’s fundamental loneliness. Even when among members of his own family, “he was so self-absorbed, so fully within his own mind and ideas, that he emerged only to share them and to have them executed.” That’s Roger Corman to a T. One big difference, though. Walt Disney, especially in the early years, could be a spendthrift. That’s why he needed his older brother to keep him on the fiscal straight and narrow. But Roger, divided soul that he is, functions as both Walt and Roy, the dreamer and the tight-fisted money guy.

I’ll be interviewing Neal Gabler on the subject of his Walt Disney and Walter Winchell biographies at the annual conference of the American Society of Journalists and Authors, April 24-26 in New York City. The public is cordially welcome to many terrific sessions.

Published on March 11, 2014 09:11

March 6, 2014

In Memoriam: Remembering Sarah Jones and the Forgotten Folk Below the Line

The annual In Memoriam segment of the Oscar broadcast is always poignant – and controversial. Emotions automatically swell when we’re reminded of the showbiz giants we’ve lost in the past year: Peter O’Toole, Shirley Temple, Harold Ramis, and so many others. Yet there are always complaints. The good people of Chicago are steamed that native son Dennis Farina was overlooked. My film noirpal Alan Rode laments the absence of Jonathan Winters. And I’ve heard gripes that Philip Seymour Hoffman didn’t deserve the climactic spot at the very end of the segment. (I disagree: of all the people on that list, his loss perhaps made me the saddest, because he had so much more to give.)

It’s tragic to lose a gifted individual because of his own bad choices. It’s even more tragic, though, to lose someone who falls victim to other people’s carelessness and bad policy decisions. Unfortunately, there’s a lot of that going on in Greater Hollywood.

In the ramp-up to the Oscars, a young woman’s death on a movie set galvanized thousands of below-the-line folk who believe their well-being is often compromised by higher-ups more worried about keeping to their schedule than about basic safety concerns. Sarah Jones, a popular young camera assistant, was killed in rural Georgia on February 20 while working on an Allman Brothers biopic, Midnight Rider. The accident is still being investigated, but it involved a scene being shot on a railroad bridge. No trains were expected: when one suddenly appeared, the crew scattered, with fatal results for Sarah, who was apparently struck by debris from a damaged prop.

Sarah’s grief-stricken co-workers launched a “Slates for Sarah” Facebook page, campaigning to have her death recognized as part of the Oscar ceremony. Though 58,000 people signed an online petition, her photo was ultimately not included in the ranks of the In Memoriam honorees. Still, Sarah got her own tiny moment. Just before the networks cut to commercial, there appeared at the bottom of my screen a small banner, mentioning Sarah and pointing the viewer toward a more complete list of passings on the Academy website, titled “Oscar Remembers.” (Sarah is represented by a full-color photograph; she’s #38 on a list of 112, tactfully arranged in alphabetical order.)

Sarah’s death has elicited grief, but also anger. Many who know the industry well are convinced that it was preventable. It seems those in charge of her set did not bother to take adequate precautions. I gather no representative of the railroad was present to oversee the filming, and just-in-case procedures were inadequate, at best. Years ago, I interviewed Haskell Wexler, the ace cinematographer who has won two Oscars for his work. Haskell, a firebrand from way back, self-financed a 2006 documentary called Who Needs Sleep? It was a plea to his colleagues to limit a film crew’s work hours, in response to the death of a cameraman in a car crash after working 19-hour-days on the film Pleasantville. Haskell’s commonsense proposal of a 12 on/12 off work day was soundly rejected, both by movie producers worried about the bottom line and by his own union colleagues, unwilling to seem weak. Today a heart-sick Haskell blames Sarah’s death on “criminal negligence.” Footnote: this would never have happened to the film’s stars, who on a set are always beautifully protected from harm.

When Hollywood’s glitterati put on their designer duds and celebrate the magic of cinema, I hope they occasionally think about the crews who make their movies possibles. Those who work the long hours and get none of the glory. And occasionally die doing what they love.

Here, from an industry web site called Stage 32, is one producer's angry and anguished reaction to Sarah's death.

Published on March 06, 2014 09:59

March 3, 2014

The Oscars as Block Party, or 3 Hours a Slave to the Tube

Well, another Oscar telecast down the tubes. Normally, I’m not a television watcher, but I always make a date with my TV set for that evening Which means I saw plenty of gorgeous gowns, fast-paced film montages, lame jokes, heartfelt thank-yous, and weird mispronunciations. (Adele Dazeem, anybody? I don’t love Idina Menzel’s rendition of the yowling power-ballad from Frozen, but didn’t she deserve to have her name announced correctly? I’m speaking to you, John Travolta.) I also saw a disheartening display of old Hollywood royalty who looked embalmed, if not pickled: Kim Novak, Goldie Hawn, Liza Minnelli. I believe in honoring the past, but trying to resurrect and freeze in place the face you had at thirty is downright scary.

An Oscar broadcast, of course, rests on the shoulders of its host. I’m old enough to remember the Bob Hope era: he was professional and funny until suddenly, as the changing realities of American life caught up with him, he was neither. Billy Crystal was reliably impish; Seth (“I Saw Your Boobs”) MacFarlane was snarky and obnoxious; the pairing of James Franco and Anne Hathaway (an obvious bid to pull in young audiences) was just a head-scratcher.

This year, of course, the Academy went back to steering an amiable course with Ellen DeGeneres. Though Ellen’s good-natured humor didn’t always land, some of her out-in-the-audience stunts were memorable for capturing the odd sense of glamorous Oscar nominees as just plain folks. As the world knows by now, she placed an order for pizza, and had world-famous celebrities in designer togs scrambling to grab a triangle of pie. (And then scrambling again to cough up the dough to pay for it. “Where’s Harvey Weinstein?” asked Ellen, knowingly.) And of course she initiated the now-famous selfie in which Hollywood royalty like Bradley Cooper, Jennifer Lawrence, and Meryl Streep appear to be as joyously silly as the rest of us when we pose for quickie cellphone shots with our pals.

But I’ve got to admit that the awards-giving was dull. Not that the winners didn’t deserve their prizes, but anyone who’d been paying attention during awards-season could guess (as I did) who would capture the major categories. Which made me realize how much more I enjoyed the Sochi Olympics, where the winners were in doubt until the heat of the moment, when someone posted the best score or crossed the finish line. Unlike a movie awards show, the Olympics occur in real-time (or tape delay, for most viewers), so the gold medal is won by an athlete fresh from the performance -- not an actor who has cleaned up, regained the lost weight, and donned fancy dress.

All this made me wish we could add suspense by rejiggering the Oscars into a you-are-there Olympic-style competition, maybe on skates. Instead of Meryl Davis and Charlie White, how about Meryl Streep and Julia Roberts as an ice dancing duo, vying against Matthew McConaughey and Jared Leto? I’d love to see Bruce Dern tossing June Squibb around in the pairs free skate. Team short-track could be represented by the 12 Years a Slave contingent, trying to muscle out the Wolf of Wall Street guys and the wily foursome from American Hustle. (Jennifer Lawrence would doubtless take yet another tumble.)

More ideas: the skinny and scary-looking Barkhad Abdi of Captain Phillips hydroplaning in the ski jump, or mixing cross-country with rifle-shooting in the biathlon. Or a hockey shootout between a determined Judi Dench on one side, an emotional Cate Blanchett on the other. And, yes, Sandra Bullock at center ice, doing spins and loop-de-loops in her underwear.

Published on March 03, 2014 13:07

February 28, 2014

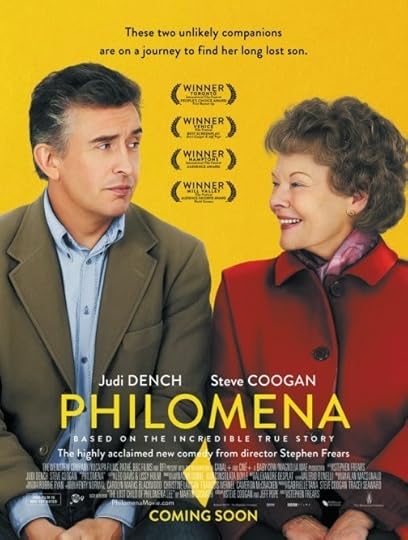

Philomena Meets Hands-On Harvey

Will a small British indie called Philomena take home any Oscars? If it does, its cast and crew will have Harvey Weinstein to thank. And they won’t be alone. Here’s a recent tidbit from the March 2014 issue of Harper’s:

Number of Academy Award winners in the past twenty years who thanked God in their acceptance speeches: 7

Who thanked Harvey Weinstein: 30

Everyone who knows something about Hollywood has heard of Harvey Weinstein. He and his brother Bob started out circa 1970 as concert promoters. Soon, taking a tip from the Roger Corman playbook of that era, they formed a company called Miramax (named after their parents, Max and Miriam) and began importing challenging art-house flicks from Europe. The strategy worked. Looking for material closer to home, they soon had some major hits on their hands. These included Errol Morris’s powerful documentary, The Thin Blue Line, and Steven Soderbergh’s provocative chamber-piece, sex, lies, and videotape, which blew away audiences at the 1989 Sundance Film Festival and went on to win the Palme d'Or at Cannes. By the time Miramax scored once again with The Crying Game, Disney was angling to buy the company for big bucks. Under the Disney umbrella, the brothers started producing as well as distributing, and the hits kept on coming. (Harvey and Bob eventually left Disney to form The Weinstein Company, though I've heard they’re now planning to buy Miramax back. But that’s another story.)

Harvey Weinstein, it goes without saying, is a control freak. It’s not unusual to see him yank a film off the distribution schedule seven weeks before its planned opening. That’s what he did in January with the Nicole Kidman starrer, Grace of Monaco, after feuding with the director over editing issues. But he’s a genius when it comes to promoting his films. Everyone in Hollywood believes it was his clever marketing that helped push Shakespeare in Love past Steven Spielberg’s Saving Private Ryan in the 1999 Oscar race.

Harvey’s films, which include the whole Quentin Tarantino canon, have continued to do well at the Oscars ever since. (He’s also been accused of trying to take down his rivals, for instance spreading rumors about some unsavory aspects of John Forbes Nash’s character when A Beautiful Mind was looking Oscar-bound.) This year, boosting Philomena along with August: Osage County and Lee Daniels’ The Butler, he has been particularly ingenious. When Philomena, the true story of an Irish mother looking for the son who was stolen from her by the Catholic Church, was rated R by the MPAA because of a few expletives dropped by Steve Coogan’s character, Harvey swung into action. He quickly persuaded the film’s star, Judi Dench, to assume her “M” role from the James Bond films to humorously threaten the MPAA in a video clip. It went viral, and soon Philomena was reclassified PG-13. That new rating made it a far more comfortable fit for the mature audiences who shy away from the sex and violence that an R-rating generally implies.

Next Harvey took advantage of opposition to the film by some Roman Catholic groups, placing enormous ads that boldly parried their complaints. But his real coup was getting the actual Philomena Lee, a charming and gutsy eighty-year-old, to show up at press events and help spread the word. Focusing on her own story rather than the film version, she has not run afoul of the Academy’s rules for Oscar campaigning. Still, her presence has its own sort of clout, and the undauntable Harvey is clearly positioning her as a potential spoiler in this year’s Oscar race.

Published on February 28, 2014 11:04

February 25, 2014

Bruce Dern: The Mouth that Roars

Last week I had another Bruce Dern sighting. I was re-watching the 2003 film Monster, in which a de-glamorized Charlize Theron plays serial killer Aileen Wuornos. There was Dern, as a kindly Vietnam vet who doesn’t realize his gal-pal is capable of murder. As always, he was wholly convincing.

Bruce Dern has racked up 144 acting credits since he started out in live TV in 1960. He’s been directed by Elia Kazan (Wild River), Sydney Pollack (They Shoot Horses, Don’t They?), Alfred Hitchcock (Family Plot), and Quentin Tarantino (Django Unchained). He earned a Supporting Actor Oscar nomination for 1978’s Coming Home. And this year he’s reveling in his Best Actor nod for Nebraska, Alexander Payne’s well-observed indie about a cantankerous old man with quixotic dreams.

It couldn’t have happened to a more interesting guy. In contrast to Nebraska’s taciturn Woody Grant, Bruce Dern is a compulsive talker. A few years back, he and I spoke about film in the Sixties. Of course we touched on Roger Corman, who directed Bruce in The Wild Angels, The Trip, and Bloody Mama. Bruce still regrets that Roger stuck to formula, and “never really chose to direct a bigger budgeted movie with a great story.” Instead, Roger’s directing career was “a continuation of the Sam Katzman drill. He became the master of it, but he’s better than what he did.”

Reminiscing about his Hells Angels role for Corman, Bruce segued into a philosophical discussion of why he adores playing bad guy roles: “When I began acting, I realized that in American historical western culture, bad guys were more celebrated in one way or another than good guys or anybody else. And the bad guys had to be celebrated, because they had game. They had social skills. They were not just mf-ers. They could play cards. They could ride. They could obviously shoot. They could obviously womanize. They could gamble. They could do a multitude of things.”

Despite his appreciation for bad guys (he shot John Wayne in the back in The Cowboys), Bruce also has high regard for the man on the white horse. Such a man was his godfather, Adlai Stevenson, who twice was the Democratic nominee for president. Bruce once asked Stevenson (his father’s law partner and best friend) how he had changed as a candidate from 1952 to 1956. Taking both his hands, Stevenson said, “Bruce, in 1952 I came in on what I thought was a fairly white horse.” Then Stevenson’s eyes filled with tears, as he continued, “In 1956, that horse was a lot greyer, and I realized I can’t do this anymore. . . . As long as you live, you can vote however you want, wherever you want, but don’t vote for that office unless you see somebody on a white horse.” Bruce sums up this surprising conversation by noting, “I’ve never voted for president in my life. Can you blame me?”

My friend and fellow writer Diana Caldwell had her own Bruce Dern encounter not long ago. She was in a Brentwood stationery store, contemplating some fancy script covers, when a tall, guy with greying hair and a raspy voice engaged her in chat. Thirty minutes flew by as he emphasized how proud he was of his actress-daughter Laura, and encouraged Diana to submit material to the writing staff of his show, Big Love. Diana insists it was no pick-up attempt: just a friendly chap who enjoyed connecting with others in the biz. At this year’s Telluride Festival, she barely missed the chance to say hello. Here’s hoping that, post-Oscars, Bruce Dern remains his approachable self.

Published on February 25, 2014 09:33

February 21, 2014

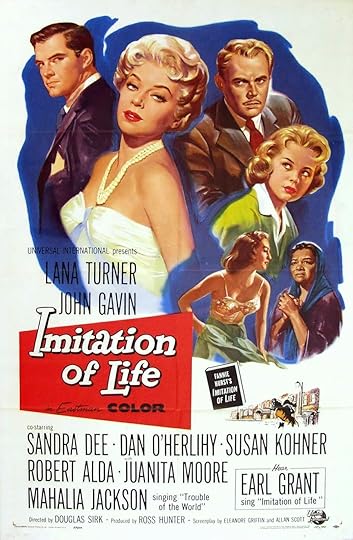

99 Years a Maid: Remembering Juanita Moore and Imitation of Life

It’s Black History Month, and 12 Years A Slave is gaining momentum in this year’s Oscar derby. Which makes this a great time to salute Juanita Moore, a 1960 Oscar nominee who died in January at age 99. Moore nabbed a Best Supporting Actress nomination for the Douglas Sirk version of Imitation of Life, playing a housekeeper who is cruelly rejected by her light-skinned daughter. After her Oscar glory (she was beaten out by Shelley Winters in The Diary of Anne Frank), Moore hoped to have her pick of challenging roles. But since black actresses usually played domestics, her career essentially stalled, though she was still performing on TV as late as 2001.

Imitation of Life, based on a tear-jerking 1933 novel by Fannie Hurst, has been filmed by Hollywood twice. The 1934 production, starring Claudette Colbert and Louise Beavers, fascinates me most. It’s the tale of two widows and their daughters. Colbert, needing help in making ends meet, joins forces with her housekeeper (Beavers) to open a pancake restaurant. Soon their packaged pancake mix becomes wildly popular, with Beavers functioning as an Aunt Jemima-like corporate symbol and earning a share of the profits. This progressive story of two women (one black, one white) successfully doing business together contrasts with more personal complications. While Colbert and her offspring melodramatically fall for the same man, Beavers grapples with the fact that her own daughter wants nothing to do with the black world, and is determined to pass for white. This daughter, Peola, is played by Fredi Washington, an African-American with fair skin and light eyes, whose unlikely looks and determination to stay true to her heritage cut her off from future opportunities in Hollywood, with studio bosses insisting she was not dark enough to be cast in “Negro” roles. (Washington later became an early civil rights activist and co-founder of the Negro Actors Guild of America.)

The 1934 Imitation of Life struggled to pass muster with the Hays Office, which opposed anything in Hollywood films that might smack of miscegenation. Though clearly the character of Peola has significant white as well as black ancestry, the issue is never addressed. And the big scene in which Peola ventures into the white world is all about being a cashier in a restaurant: there’s no sexual undercurrent, no confrontation with a white suitor newly aware of her past.

The 1959 film starring Lana Turner and Juanita Moore changes a lot. Now the leading white character is a glamorous actress, and Moore plays her maid and confidante. Adorable Sandra Dee is Turner’s daughter, while John Gavin is cast as the photographer for whom they vie. Once again, the black daughter (renamed Sarah Jane) rejects the facts of her birth in order to pass as white, appalling Moore, who intones, “It’s a sin to be ashamed of what you are. . . . The Lord must have had his reasons for making some of us white and some of us black.” But the old taboo that barred scenes between a black woman and a white man is gone now, leading to the dramatically charged moment when Sarah Jane is beaten by her white boyfriend and left bleeding in the gutter. In any case, the taboo might not have mattered, because Sarah Jane is played by Susan Kohner, dark-eyed daughter of a Mexican mother (Lupita Tovar) and an Eastern European Jewish father (Hollywood superagent Paul Kohner). Susan Kohner is hardly African-American, but she, like Moore, was Oscar-nominated for her powerhouse performance.

Happily for Lupita Nyong’o, today’s Hollywood can appreciate a black actress playing a black role.

Published on February 21, 2014 10:46

Beverly in Movieland

I write twice weekly, covering topics relating to movies, moviemaking, and growing up Hollywood-adjacent. I believe that movies can change lives, and I'm always happy to hear from readers who'd like t

I write twice weekly, covering topics relating to movies, moviemaking, and growing up Hollywood-adjacent. I believe that movies can change lives, and I'm always happy to hear from readers who'd like to discuss that point.

...more

- Beverly Gray's profile

- 10 followers