Beverly Gray's Blog: Beverly in Movieland, page 121

April 29, 2014

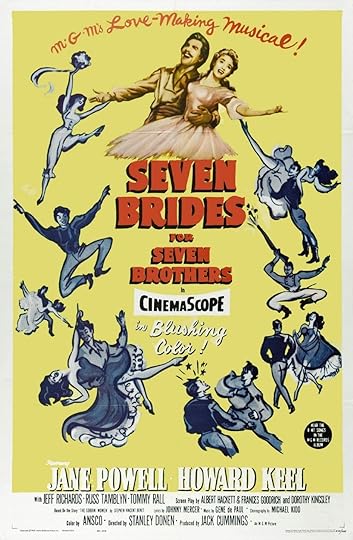

Seven Brides for Seven Brothers: What’s Love Got to Do With It?

The number of dancing Pontipee brothers is rapidly dwindling. Those who know and love the exhilarating MGM musical, Seven Brides for Seven Brothers (1954), will understand what I’m talking about. This is one musical (West Side Story of course is another) that glories in the ability of young males to look macho while moving to music. Eldest brother Adam, played by the ultra-virile Howard Keel, didn’t dance, but he used his resonant baritone to great effect in this film about love and courtship in Oregon territory, circa 1850. Keel passed on in 2004. Second brother Benjamin (Jeff Richards) is also no longer with us. It’s taken me years to realize that “Benjamin”— in real life a former baseball player—doesn’t truly take part in Michael Kidd’s breathtaking ensemble choreographies. You generally find him hanging around in the background, sometimes in the company of Julie Newmar, who was still billed as Julie Newmeyer back then.

The number of dancing Pontipee brothers is rapidly dwindling. Those who know and love the exhilarating MGM musical, Seven Brides for Seven Brothers (1954), will understand what I’m talking about. This is one musical (West Side Story of course is another) that glories in the ability of young males to look macho while moving to music. Eldest brother Adam, played by the ultra-virile Howard Keel, didn’t dance, but he used his resonant baritone to great effect in this film about love and courtship in Oregon territory, circa 1850. Keel passed on in 2004. Second brother Benjamin (Jeff Richards) is also no longer with us. It’s taken me years to realize that “Benjamin”— in real life a former baseball player—doesn’t truly take part in Michael Kidd’s breathtaking ensemble choreographies. You generally find him hanging around in the background, sometimes in the company of Julie Newmar, who was still billed as Julie Newmeyer back then.Thank goodness the three youngest of the alphabetically-named Pontipees are still alive and kicking. Jacques d’Amboise, now 79, took a leave from the New York City Ballet to play brother Ephraim. He later became a respected dance teacher, was the focus of the Oscar-winning He Makes Me Feel Like Dancin’, and is currently on view in a new documentary, Afternoon of a Faun, about the tragic Balanchine ballerina, Tanaquil LeClercq. Tommy Rall, who played hyper-intense Frank, last appeared as a werewolf in a goofy Roger Corman comedy on which I worked, Saturday the 14th Strikes Back. Russ Tamblyn, who showed off his gymnastic talents as youngest brother Gideon, is best remembered as Riff, the leader of the Jets, in West Side Story. He’s still performing, and has also contributed daughter Amber to show biz.

But we lost Matt Mattox (Caleb) in 2013: he was the one who retained a beard and mustache even after the brothers cleaned up at the film’s midpoint, and he did a memorable solo dance in a number called “Lonesome Polecat,” in which the men lament the lack of women in their winter hideaway. (As Johnny Mercer’s lyrics remind us, “A man can’t sleep/When he sleeps with sheep.”) The film’s Daniel, Marc Platt -- not to be confused with a major Hollywood producer who bears the same name – passed on just recently, at the end of March, 2014.

The best way to see the dancing Pontipees in action is to take a gander at the film’s famous barn-raising sequence. Anyone who enjoys the competitive aspects of Dancing with the Stars will relish what happens when the brothers try to outdance some town dandies to win the affections of the local womenfolk. Dancing as somehow unmanly? Not here.

But in one respect the “manly” men of Seven Brides for Seven Brothers give me pause. The film’s plot derives from a short story, “The Sobbin’ Women,” by Stephen Vincent Benét. It’s a folksy bit of backwoods Americana, but it’s based on a rather odious legend about how the men of ancient Rome, in desperate need of wives, helped themselves to the women of the neighboring Sabine tribe. What’s generally referred to as the Rape of the Sabine Women has often been portrayed in classical paintings. If you happen to be female, it doesn’t look like much fun. Of course in the MGM version, the “brides” who are abducted by seven wrong-headed males—following a period of outrage and some serious scolding by Adam’s wife (the adorable Jane Powell)—are all too ready to fall for their captors. Which makes for a happily-ever-after fadeout. But is this love, or Stockholm Syndrome?

"The Rape of the Sabine Women" (1636) by Nicholas Poussin

"The Rape of the Sabine Women" (1636) by Nicholas Poussin

Published on April 29, 2014 13:44

April 25, 2014

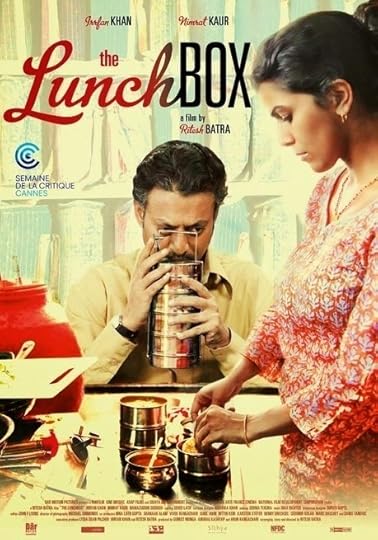

The Lunchbox: A Tasty Treat from India

Since I love great meals, there’s a special place in my heart (and in my stomach) for movies that focus on the preparing, serving, and savoring of food. Of course Babette’s Feast leads the list, along with Big Night, and (for those of us who are passionate about Chinese cooking) Ang Lee’s Eat Drink Man Woman. Fans of dessert (and who isn’t?), agree that Chocolatis simply scrumptious. Ratatouille may be a work of animation, but it also effectively conveys the joy of cooking, as well as the joy of eating. As does, in its own way, Julie & Julia. Not to mention that wacky Japanese “noodle western,” Tampopo.

India’s The Lunchbox, a major international hit at last year’s Cannes Film Festival, is about food too: about the effort that goes into cooking and the pleasure that comes from tasting. I must admit that, although I love the spicy cuisine of the Indian subcontinent, the dishes prepared in this film are not things of beauty. There’s no sense of a behind-the-scenes food stylist making every ingredient look like a precious jewel and the assembled components as gorgeous as a High Baroque still-life. But, of course, this isn’t some Bollywood fantasy, with a bevy of beautiful women singing and dancing their way through a pristine kitchen set. It’s a small-scale realistic drama, though one that takes off from Mumbai’s complex dabbawallah system, in which hot lunches are delivered from the hands of their makers to the desks of cross-town office workers who crave a lovingly prepared hot meal at midday.

The system is apparently a model of efficiency, but this film (by debuting writer-director Ritesh Batra) hinges on the results of a bureaucratic error. Ila, a young wife trying to hold onto her husband’s heart by way of his stomach sends off a lunch that ends up in the hands of a lonely widower working at a soulless clerical job. Saajan Fernandez is played by Irrfan Khan, memorable from both Slumdog Millionaire and The Life of Pi, where he had the brief but essential role of the title character as an adult. Here he’s a dour low-level bureaucrat, quick to find fault with others’ imperfections, but not immune to home-made curries and dals spooned into tidy little metal dishes. He scribbles a note to the unknown cook – a complaint about salt – and a correspondence begins. That, in a nutshell, is the movie. Following the great old tradition of epistolary novels and such films as The Shop Around the Corner and 88 Charing Cross Road, this is an epistolary movie, in which the main characters only cross paths when they put pen to paper. (No text messages or “You’ve Got Mail” here.) Which is not to say that nothing happens. The two principals evolve a good deal from start to finish. As befits a romantic drama with realistic roots, there’s no pie-in-the-sky (or even “Pi in the Sky”) ending. But rest assured that the plot has its share of surprises and suspense.

The smaller roles add both poignancy and humor. They include Ila’s downtrodden mother, and Saajan’s unrelentingly cheerful young business colleague, a pain-in-the-neck fellow who contributes in his own way to the leading man’s character development. Then there’s the unseen but often heard “Auntie” who advises Ila on her cooking skills from her upstairs flat, and sometimes sends down Care packages via a nifty suspended basket. Also a character of sorts is grubby, bustling, bursting-at-the-seams Mumbai, which is apparently a splendid place to do lunch.

Which reminds me -- it's time to eat!

Published on April 25, 2014 13:35

April 21, 2014

Jim Henson: Had He But World Enough, and Time . . .

Miss Piggy is reclining gracefully on a sofa, picking Kermit-green pistachios out of a crystal goblet, and intoning “He loves me . . . he loves me not.” It’s all part of a TV commercial designed to promote both Wonderful® Pistachios (slogan: “Get Crackin’”) and the new Disney release, Muppets Most Wanted. Which means a Jim Henson creation is back where it all started, in the wonderful world of advertising.

Jim Henson was astonishingly young when he started earning a good living by creating wacky commercial messages for a local brand, Wilkins Coffee. The brand-new medium of television proved to be immensely hospitable to a tall, lanky fellow in his early twenties with an offbeat sense of humor, an inexhaustible work ethic, and a trunkful of what he called “muppets.” It was not that Jim aspired at first to be a great puppet master. Puppetry was one of the many tricks he had up his capacious sleeves as he sought to live a life that was creative, constructive, and fun.

I learned a vast amount about Jim Henson from a best-selling new book by my friend and colleague, Brian Jay Jones. His Jim Henson: The Biography has the advantage of loving input from Henson’s ex-wife and five children, all of whom had been close Henson collaborators in the course of his varied career. Though Jim was not the easiest of spouses, he was clearly an exemplary father, and his sense of kinship with children everywhere contributed hugely to his success. Still, he by no means wanted to be remembered solely as a entertainer for the small-fry set. Throughout his relatively brief life (he died at 53), his artistic ambitions never quit.

Case in point: in 1965, not yet 30, he stepped away from puppetry to write, produce, direct, and star in a short experimental film. The full implications of “Time Piece” (see below) cannot be pinned down, but Henson brilliantly uses percussion, animation, montage, and other audio-visual tricks to capture -- in nine brief but potent minutes -- a sense of a man succumbing to the pressures of a life that’s rapidly ticking away. It’s definitely not for the kiddies, and there’s not a Muppet in sight. “Time Piece” was nominated for an Oscar in the category of Best Live-Action Short. He didn’t win, but eventually a long slew of Emmys would grace his mantel.

Jim Henson never shrank from a technological challenge, nor from an artistic one. It had not occurred to me before reading this book that puppeteers like Henson, who work with their hands inside their characters, are always faced with the need to stay out of sight. When you’re six foot three, this isn’t easy—especially when, as in the opening of The Muppet Movie, Kermit the Frog is perched on a log in the middle of a swamp. To achieve the first impression of a banjo-playing Kermit surrounded by water, Jim squeezed himself into a cramped diving bell in a studio backlot tank, then manipulated his character from underwater. (In The Great Muppet Caper, Henson and his team topped themselves with a Miss Piggy-starring water ballet.)

I return to “Time Piece” because it captures something fundamental in Jim’s nature -- a feeling that life is short. The words of poet Andrew Marvell probably resonated with Jim: “But at my back I always hear/ Time’s wingéd chariot hurrying near.” His brother died young, and he himself seemed to need to live fast and cram in many projects at once. But when he died in 1990, from a sudden but devastating illness, it’s amazing how much he’d accomplished.

Brian Jay Jones will be one of my three panelists on Saturday, May 17 at the conference held by BIO –the Biographers International Organization – on the Boston campus of the University of Massachusetts. We’ll be discussing “Getting the Family on Board,” a subject about which Brian knows a great deal. The public is cordially invited.

Published on April 21, 2014 12:00

April 18, 2014

Zelda Gilroy for Supervisor, or The Many Campaigns of Sheila Kuehl

If you’re old enough to have seen The Many Loves of Dobie Gillis, an amiable sitcom that rocked the airwaves from 1959 to 1963, then you remember Zelda Gilroy. The central character of this series based on Max Shulman’s satiric stories is Dobie Gillis, a romantically-inclined teenage boy who is putty in the hands of any girl who’s “creamy,” to crib from the language of the show’s theme song. Dobie (played with innocent zest by Dwayne Hickman) is particularly drawn to voluptuous airheads, like Tuesday Weld’s Thalia Menninger. But, alas, dim Dobie himself proves irresistible to the class brainiac, feisty little Zelda. She shows her love by crinkling her nose at Dobie (he always reflexively crinkles back, then recoils in horror), and by volunteering to do his homework.

Zelda was memorably played by Sheila James, whose real name is Sheila Kuehl. Today she’s convinced that she snagged the role of Zelda because she was even shorter than series creator Max Shulman. When Dobie Gillis became a hit, Shulman did her another favor: persuading her to continue with her studies at UCLA, despite the demands of her showbiz career. Eventually she became UCLA’s Associate Dean of Students and then, at age 34, entered Harvard Law School. Presumably her acting experience came in handy: she was only the second woman in the school’s history to be named the winner of its Moot Court competition. (I presume she used no nose crinkles to win over the judges.) Then it was back to California, where she launched a career in the state legislature.

I tend to be suspicious of actors who go into politics, but Sheila Kuehl is the real deal. She has served honorably in both California houses, accepted many committee posts, championed important social legislation, and earned a reputation for working well with colleagues on the other side of the aisle. She’s also my neighbor, making her home not far from me in the great little city of Santa Monica. Now that she’s termed out of the state legislature, Sheila is running to be one of Los Angeles County’s five supervisors. The district covers an enormous area, and she needs to woo a million voters. Which is why I attended an unusual fundraiser on the Sunset Strip.

“Zelda for Supervisor” was the evening’s theme, and we were all encouraged to dress in our Fifties best. This being Hollywood, speeches were made by some showbiz names: actor-environmentalist Ed Begley Jr. and funnyman Bruce Vilanch, who couldn’t resist a Sarah Palin (“Caribou Barbie”) gibe. But the star of the evening was Zelda Gilroy, whom Kuehl herself described with typical enthusiasm as a role model for ambitious young women because she never took No for an answer. Several Dobie Gillis episodes were aired, including one in which Zelda—making her usual passionate pitch for Dobie’s love—proposes to become his campaign manager and get him elected to Congress. Ah, yes. The fabulous 1950s, when no one realized that Zelda herself would have made a much better candidate.

Much like Sheila Kuehl, who freely admits that her character shared many of her own personality traits. Persistence, for one thing, and a willingness to get creative if it will help her reach her goal. Far from shunning her TV past, Sheila glories in it, especially when it extends the reach of her campaign. Shilling for contributions, she announced, “I’ll call you ‘poopsie’ for twenty bucks.” Or, for $100, you can get a nose crinkle.

Published on April 18, 2014 15:23

April 15, 2014

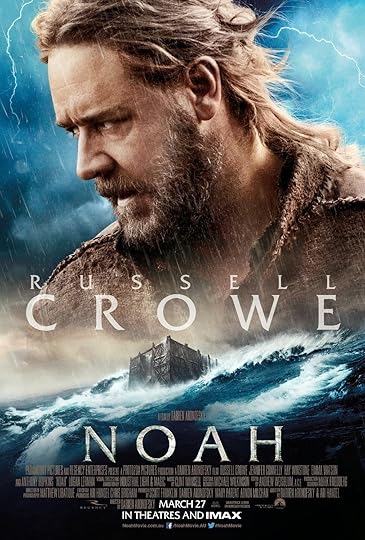

Noah’s Art: Bespoke Tailoring and the Movies

How did Noah fasten his clothing? At my local upscale cineplex a display case always houses a few costumes featured in some major new release. Recently I studied the drab, rough-hewn tunic worn by Russell Crowe for at least forty days and forty nights in Darren Aronofsky’s controversial blockbuster. I leave it to others to ponder Aronofsky’s vision, and whether it’s compatible with the Biblical account of Noah and the flood. Me—I wanted to check out Noah’s buttons, or the lack thereof.

My fascination with buttons comes from having read a fascinating new book called The Coat Route: Craft, Luxury & Obsession on the Trail of a $50,000 Coat. Travel writer Meg Lukens Noonan (like me a member of the American Society of Journalists and Authors) discovered that a fourth-generation tailor in Sydney, Australia had just made, for a customer with deep pockets, the world’s most sumptuous overcoat. Nothing gaudy, you understand. Tailor John H. Cutler just started with a rare and costly fabric (the fleece of a small, shy Peruvian critter called a vicuña), added a stunningly patterned silk lining (from top Italian designer Stefano Ricci), then finished off his creation with buttons molded from the horns of an Indian water buffalo by an English firm that has been doing this for 150 years. While chasing down every aspect of the fabulous coat, Noonan mulls over the fine art of bespoke tailoring. It’s in some ways the opposite of high fashion: those who’ve embraced bespoke don’t go in for flashy trends and the constant need to update one’s wardrobe. Bespoke garments, though exquisitely crafted, are subdued. And they’re intended to last for decades.

I learned from Noonan’s book about the grand tradition of Savile Row. Since the early nineteenth century, English gentlemen have come to this London street to be fitted for suits designed especially for them. Noonan vividly describes one establishment, Anderson & Sheppard, where “a hushed front room glows with an amber light, as if viewed through a glass of sherry.” Among its elite clientele have been some of the entertainment world’s most glamorous folk: Rudolph Valentino, Duke Ellington, Fred Astaire, even Marlene Dietrich, who famously favored man-tailored ensembles.

During the golden age of moviemaking, studios with well-appointed costume shops had their own version of bespoke tailoring. The stars were outfitted head to toe in garments specially made to suit their bodies as well as their roles. Such famous studio designers as Edith Head made a career out of fitting and flattering. Deborah Nadoolman (Raiders of the Lost Ark) has griped to me that, because of today’s lower budgets, a costume designer is now often treated as a “costumer,” whose job is to go out shopping for appropriate items.

In today’s world, where disposable fashion rules, few customers have the money and the patience to have their wardrobes made to order. That’s why the craftsmen to whom Noonan spoke (like those English button experts) are a dying breed. Still, there’s hope: the popularity of Downton Abbey has encouraged enthusiasts to seek out bespoke tailors and cobblers who can help transform them into English country gentlemen.

And what of Noah? In place of buttons, his tunic is closed with crude loops and tabs, quite appropriate since the first button-holes didn’t appear until the thirteenth century. I can’t imagine this highly individual garment on the rack at H&M. And it was surely hand-loomed and fitted to Crowe’s frame. So, although the look is hardly that of an English gentleman, it may be fair to call Crowe’s costume “bespoke.” Thanks to Noonan, I now get to ponder questions like these.

Meg Lukens Noonan will appear on my panel, ASJA Award-Winners: Making it from Pitch to Publish, at this year’s ASJA conference, coming up on April 24-26 at the Roosevelt Hotel in New York City. The public is cordially welcome.

Published on April 15, 2014 10:45

April 11, 2014

And A Little Child Shall Lead Us: Remembering Shirley Temple and Mickey Rooney

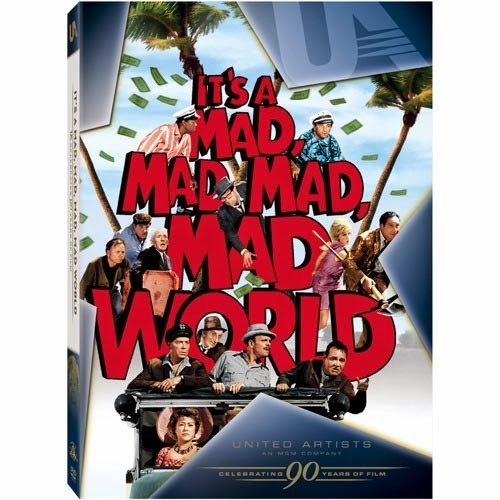

Since the start of 2014, two of America’s most priceless child stars have left us. Shirley Temple passed away in February, at age 85. From 1935 to 1938, the winsome moppet was the nation’s top box-office draw, singing and dancing her way into everyone’s hearts. Then, this past Sunday, we lost Mickey Rooney, who held on until age 93. In July 2012, after an Academy screening of It’s a Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World, I remember how he came out on stage and somehow pulled off a few dance steps. That was Mickey Rooney: a trouper till the end. Both Temple and Rooney found fame during the Great Depression, when Americans ground down by years of unemployment were desperate for low-cost entertainment. Films starring cute, plucky youngsters nicely filled the bill. Shirley’s wholesome family movies, in which she tap-danced with Bill “Bojangles” Robinson and jousted with cantankerous Lionel Barrymore, were designed to lift people’s spirits, and so they did. But by the time Shirley entered adolescence, the studios no longer knew what to do with her. There was serious hype around her first screen kiss, but the public wanted her to stay a little girl forever. That’s where my family came in. Why did my father’s parents—poor immigrants with too many kids and not enough money—move from the Midwest to California circa 1935? Naturally, to get the youngest daughter into the movies. She had curly hair and presumably could carry a tune, so it seemed obvious that she was bound for stardom. It didn’t happen, but eventually my father met my mother at UCLA . . . and the rest is (family) history.

Eventually Shirley Temple was smart enough to realize that there were no more movies in her future. She retired, married, raised three kids. Then, to everyone’s surprise, she got political. She was selected by Republican presidents to serve as a UN representative, an ambassador to Ghana and later to Czechoslovakia, and the U.S. Chief of Protocol. By all reports she filled these positions with grace.

I first learned of Shirley at a Brownie Scout meeting, when it was announced we’d be seeing a traveling exhibit that featured her enormous doll collection. (She’d been given hundreds of dolls by admirers all over the world.) Our leaders were amazed and amused that none of us had ever heard of Shirley Temple. But that would soon change. Television execs were soon to greenlight Shirley Temple’s Storybook, an anthology of fairytale adaptations, with the now-adult Shirley hosting as well as playing an occasional role. And old Shirley Temple movies suddenly became a TV staple. Like our parents, we Baby Boomers fell for her too. Mickey Rooney was as plucky as Shirley in his movie roles, but had a far wider range. He played Puck in Warner Bros.’ all-star Midsummer Night’s Dream (1935), went dramatic in Boys Town (1938), and, as the All-American Andy Hardy, embodied everyone’s favorite kid brother. Once he grew up (but only to 5’3”) he kept at it, appearing in somber dramas, wacky comedies, family features like The Black Stallion, and even Roger Corman flicks. A friend of mine who once taped many celebrity interviews for A&E Biography explained why Rooney was a valued presence on the set. Once he was paid a substantial “honorarium,” he’d turn on the star power, improvising a heartfelt tribute to the subject at hand, often becoming dramatically tearful. But now his large extended family is battling over the old pro’s will and final resting place. Family feuds are ugly things. So let’s call up some tears, shall we?

Published on April 11, 2014 11:15

April 8, 2014

Roger Corman at 88: Approaching the King Lear Years

On April 5, 2014, Roger Corman celebrated his eighty-eighth birthday. At this stage of his long career, he’s enjoying plenty of respect, even veneration. (On my Roger Corman: Blood-Sucking Vampires, Flesh-Eating Cockroaches, and Driller Killers Facebook site, one of his loyal fans recently referred to him as “The God Who Walks Among Us.”)

As author of the definitive Corman biography, which was updated last fall with a brand-new epilogue, I’m often asked what my former boss is doing now. As a matter of fact, Roger has done rather well since he turned eighty. His tongue-in-cheek monster mash-ups for the Sci Fi Channel, which now calls itself Syfy, have made him popular with a whole new audience. And, in the course of promoting such made-for-TV schlockfests as Dinocroc vs. Supergator, he’s become something of an Internet celebrity as well.

Here’s how I kick off “The Epilogue Strikes Back”:

Fade in on a pristine stretch of tropical shore, where we spot an old codger with his shirt unbuttoned halfway down his chest. Though sloppy and unshaven, he looks a lot like Roger Corman. Sauntering along, he ogles a bikini-clad lovely who has just bent down to dig up a rare coin. When a tentacled sea-beast unexpectedly looms, dragging the shrieking beauty into the surf, he reacts with mild surprise. Then, shrugging off the carnage, he makes a beeline for the coin she’s dropped in the sand. The scene ends on his self-satisfied grin.

In February 2011, Roger and Julie Corman visited the set of theflickcast.com to promote their latest made-for-TV movie, Sharktopus. On the webcast, a genial Corman explained that it was director Declan O’Brien who had proposed this out-of-character cameo appearance. Roger readily went along with the gag, because “I’ve played so many governors and senators—I said I’d be delighted to play a beach bum.” Host Matt Raub underscored for viewers the scene’s sly allusion to Corman’s “well-known aversion for letting good money go to waste,” and Roger agreed with a twinkle, “Exactly!”

Roger was having fun here spoofing his cheapskate image. But he has also been enjoying his new reputation as one of Hollywood’s elder statesmen, with all the glory that entails. In November 2009, he was chosen by the Academy of Motion Pictures Arts and Sciences to receive an honorary Oscar for his contributions to the film industry. At the Academy’s newly inaugurated Governors Awards banquet, such Corman alumni as Ron Howard and Jonathan Demme hailed their former boss, while longtime admirer Quentin Tarantino waxed poetic: “Roger, for everything that you have done for cinema, the Academy thanks you, Hollywood thanks you, independent filmmaking thanks you, but most importantly—for all the wild, weird, cool, crazy moments you’ve put on the drive-in screens—the movie-lovers of the planet Earth thank you!”

In the years since 2009, Roger has been the star of at least one documentary (Alex Stapleton’s Corman’s World), has made countless personal appearances, and (though he doesn’t personally do email or own a cellphone) encouraged his staff to come up with clever ways of using Twitter and social media to promote the Corman brand. Getting older, though, hasn’t always been easy for him. A recent staffer described to me his short attention span, his frequent bursts of anger, and occasional threats to shutter the company. He and his wife Julie have also been rocked by a nasty lawsuit served against them by their two adult sons, who claim more of the Corman loot for themselves. It’s sad that Roger, at eighty-eighty, is now facing what a Corman veteran calls “the King Lear years.”

Low-key commercial message: Yes, I really am an expert on all things Roger Corman. My newly updated biography, Roger Corman:Blood-Sucking Vampires, Flesh-Eating Cockroaches, and Driller Killers, has won praise in such varied publications as Variety, the New York Times, Video Watchdog, and the Wall Street Journal,. It has also been hailed by several generations of Corman alumni as an accurate and insightful look at a very complex man. Click here to find out more.

Published on April 08, 2014 12:11

April 4, 2014

Noah and Cesar Chavez Approach Biopic Heaven

In light of two films that opened last weekend, I’m pondering exactly what a biopic is. Cesar Chavez, a respectful salute to the Chicano labor organizer, earned tepid reviews and modest returns at the box office. And then there was Noah, which over the weekend collected a cool $44 million domestically, plus another $95 million overseas. This despite protests from those concerned that Darren Aronofsky’s Bible epic misrepresents the word of God.

Cesar Chavez was very much a living figure when I was growing up. I well remember sitting down with fellow grad students for a picnic lunch. Suddenly we were all staring at the one newcomer to California who had innocently unpacked a bunch of grapes. It was the era of the grape boycott in support of farm workers, and none of us had eaten grapes in years. Chavez and his movement did a lot of good for those at the bottom of the social ladder. Still, Chavez was—like most great leaders—a sometimes problematic human being. An important new biography by Miriam Pawel, who like me is a member of Biographers International Organization, is catching flak from Chavez admirers because it dares to point out the great man’s flaws. This film apparently goes the other route; critics are griping that it makes Chavez seem little lower than the angels.

Which of course is a complaint that’s been leveled at many biopics, like Richard Attenborough’s reverent 1982 film, Gandhi. Hollywood, especially in its early days, liked nothing better than to present an historical figure as a hero: hence admiring (though heavily fictionalized) films about such high achievers as Emile Zola and Louis Pasteur. Today we tend to be fascinated by the reality behind the legend. For me one of the triumphs of Spielberg’s Lincoln was that it presented an admirable man, but not a flawless one.

A biopic can never be accepted as true biography because it involves actors taking on roles, and because there’s necessarily a compressing and a rearranging of incidents in order to tell a coherent story in a few hours’ time. Biographers, on the other hand, pride themselves on the lengths they will go to know everything about their subject. They conduct countless interviews, search through dusty archives, and chase down every possible lead. (No wonder biographies tend to be so very long.) A filmmaker might do some of the same research, but in the service of a relatively concise work of art, which means making major choices about what to condense and what to leave out.

I’m boggled by the fact that some religious folk are ready to condemn Noah, sight unseen, because they suspect it distorts the truths they find in the Bible. But a filmmaker working with the Bible is hardly overwhelmed by usable details. In the Book of Noah, we learn a fair amount about the size of the ark and the height of the waves, but virtually nothing about the key personalities involved. Like: how does Mrs. Noah feel about all this? And why exactly does Noah get drunk and get naked in his post-flood vineyard? And, if the children of Noah’s sons are expected to repopulate the earth, where exactly are they going to find mates who aren’t their first cousins? All of this is, needless to say, subject to interpretation. There are no eyewitnesses to interview, no old letters to study, so the filmmaker can only try to approach the text seriously and with good intentions. Aronofsky’s take on the Noah story may be a bit bonkers, but it’s hard to say it’s wrong.

Fans of biography may want to join me at this year’s conference of BIO, also known as the Biographers International Organization. It all happens on the University of Massachusetts’ Boston campus on Saturday, May 17. The public is most welcome.

Published on April 04, 2014 10:46

April 1, 2014

Consciously Uncoupling: L’Wren Scott Chooses Death

I don’t like making fun of the dead. And, even more than Mick Jagger, I have no special insight into why fashion designer L’Wren Scott took her own life. Using, apparently, a noose made from a silk scarf. That fashionista detail, I must admit, really gives me pause.

Scott’s death on March 17, 2014, naturally set tongues to wagging. I overheard several sensible people I know, one of whom had attended a social function at which Scott was present, speculating that her desperate act could be blamed on a negative body image. After all, she had worked both in Hollywood (as stylist and costume designer) as well as in the world of high fashion, two realms where you can never be too rich or too thin. A quote attributed to her caught my eye: “I've never met a woman who thinks she's got a good enough figure.” Then there was the perhaps meaningful fact that she was facing a Big Birthday. On April 28 of this year, she would have been fifty years old.

All this is purely speculation on my part. Perhaps whatever destroyed her spirit had nothing to do with her appearance. She was 6’3” and a former fashion model, so perhaps she had the chutzpah to look however she chose. Certainly the fact that for thirteen years she gave satisfaction to Jagger, one of the world’s most interesting men, should have validated her sense that she had a lot to offer. Maybe, as some have speculated, she was depressed over business reverses, or health issues, or some such.

But I continue to be haunted by the notion that a life in showbiz (or on its fringes) requires women to be obsessed with their looks. Years ago, I knew a performer who wanted to make it big. She had loads of musical talent, but someone must have told her that she’d be even prettier if she improved the line of her chin. Next thing I knew, she’d had a drastic surgery that broke her jaw and required her mouth to be wired shut for months. The end result: she looked really nice, but of course she hadn’t looked bad to begin with. And I’m not sure that the change advanced her career one iota.

I also knew a former child star who quit the industry in her teen years. Decades later, her sister told me that one reason she’d said goodbye to her career was the pressure she faced in late adolescence to undergo breast augmentation. One young actress who succumbed to this pressure was Mary Elizabeth McDonough, well-known as the middle child on The Waltons. In her memoir, she recounts how she agreed to silicone breast implants, then years later found herself battling lupus, perhaps an aftereffect of the surgery.

We all know that tall, blonde, lithe Gwyneth Paltrow pretty much meets Hollywood’s standards of female perfection. But even she is capable of feeling insecure. I interviewed Gwyneth for The Hollywood Reporterwhen she was carrying her first child. Hoping to make an emotional connection, I commiserated on the discomforts of late-stage pregnancy. She plaintively told me how tough it was for her to see on TV another tall blonde glamour girl—Cameron Diaz—looking gorgeous, while she herself felt as big as a house. Obviously, Gwyneth got her pre-baby body back, and then re-made herself as a lifestyle expert. Now that she and her hubby, rocker Chris Martin, have decided on “conscious uncoupling,” as she so coyly puts it, I hope she’ll remain satisfied with who she is, no matter what she looks like.

Published on April 01, 2014 13:21

March 28, 2014

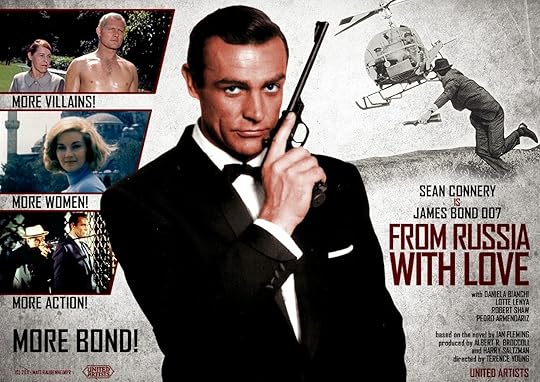

Four Who Dared (to be James Bond, American-Style)

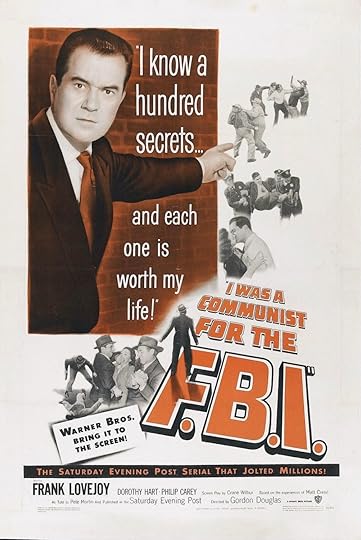

I’m too young to have ever seen a 1951 drama with a provocative title, I Was a Communist for the FBI. I do recall my parents tuning in to a related TV series, I Led Three Lives (1953-1956). In both, an All-American good guy joins the Communist Party to spy on behalf of the red, white, and blue. Such was life in the 1950s, when those in the know were spotting saboteurs and commie stooges under every bed.

Evan Thomas, eminent historian and biographer, published in 1995 a fascinating book called The Very Best Men. Subtitled Four Who Dared: The Early Years of the CIA, it offered an inside look at a shadowy organization I knew little about, one established at the close of World War II to combat the red menace beyond U.S. borders. (By contrast, J. Edgar Hoover and the FBI were rooting out Communist infiltration on American soil.)

This was the era when Ian Fleming was starting to publish his James Bond novels. They reached U.S. shores by the late Fifties, and the first film followed in 1962. President Kennedy was one of many serious devotees; politicians as well as Americans of every stripe were agog at the idea of secret agents heroically (and with flair) keeping us safe from the evil forces that threatened our way of life. Thomas himself notes that “at a time when J. Edgar Hoover was still a national hero, there was no reason for the public to believe that the CIA was any less noble.”

The men who led the early CIA turn out to be a colorful bunch. Thomas focuses on four of them—Frank Wisner, Des FitzGerald, Tracy Barnes, and Richard Bissell—who had several things in common. They were all smart, brave, well-educated, and patrician. (Many CIA higher-ups followed a trajectory from Groton, one of the nation’s toniest prep schools, to Yale.) They tended to dislike administrative duties, and far preferred being where the action was, in faraway places where they could foment coups and otherwise disrupt Soviet influence. They loved spontaneity, and had little use for oversight, especially from other branches of the U.S. government. They sometimes succeeded brilliantly, but often made a hash of things.

The fingerprints of the CIA were everywhere in this era. They scared a Guatemalan president out of office and helped install as Iran’s prime minister a general so panicked by his new responsibilities that a CIA agent had to help him button his uniform collar on the day of the coup. They tried to depose Sukarno of Indonesia by shooting a pornographic movie in which a lookalike was seduced by a sexy Soviet spy posing as a flight attendant. As the Sixties wore on, many CIA hands became obsessed with destabilizing Cuba’s Castro regime. They quickly moved from schemes designed to embarrass Castro—like using a depilatory powder to make his beard fall out—to outright assassination attempts involving poisoned pens, poisoned diving suits, exploding seashells, and bacteria-laced cigars. None of this, obviously, makes the CIA look very good.

The lives of the four men profiled by Thomas did not turn out well. One killed himself; two ended their careers in disgrace; only one lived beyond the age of 62. When Tracy Barnes read John Le Carré’s bitter The Spy Who Came in from the Cold, he recognized its essential truthfulness about the burden of a covert life. According to his daughter, “It was like it hit him, that this really was a dirty business, no more James Bond . . . but rather a creature that eats its own.”

Evan Thomas (most recently the author of Ike’s Bluff: President Eisenhower’s Secret Battle to Save the World) will be featured on the panel I’m moderating at a conference sponsored by the Biographers International Organization. Other panelists, including Will Swift (Pat and Dick: The Nixons, an Intimate Portrait of a Marriage) and Brian Jay Jones ( Jim Henson: The Biography ) will join Evan in exploring the topic “Getting the Family On Board.” It all happens on the University of Massachusetts’ Boston campus on Saturday, May 17. The public is most welcome.

Published on March 28, 2014 10:54

Beverly in Movieland

I write twice weekly, covering topics relating to movies, moviemaking, and growing up Hollywood-adjacent. I believe that movies can change lives, and I'm always happy to hear from readers who'd like t

I write twice weekly, covering topics relating to movies, moviemaking, and growing up Hollywood-adjacent. I believe that movies can change lives, and I'm always happy to hear from readers who'd like to discuss that point.

...more

- Beverly Gray's profile

- 10 followers