Beverly Gray's Blog: Beverly in Movieland, page 124

January 14, 2014

Peter and the Starcatcher Take Up Recycling (just like Roger Corman)

As a fan of live theatre, as well as someone who grew up loving J.M Barrie’s Peter Pan, of course I didn’t want to miss Peter and the Starcatcher. This stage adaptation of a popular children’s novel is a prequel of sorts to the Peter Pan story, showing how the boy who didn’t want to grow up landed on a island paradise, and how an ornery pirate came to fear a ticking crocodile.

It’s a lovely show, one that makes full use of the imaginative possibilities of live theatre. The one-dozen actors play many roles, and the audience needs to stay focused in order to appreciate the play’s inventive language and exuberant stretches of mime. But during the annual Broadway awards season, it was the technical crew who captured the Tonys. At the 2013 ceremony, there was a rare unanimity among Tony voters: Peter and the Starcatcher was honored for its sound design, lighting design, costumes, and scenery.

Taking a gander at an article in the play’s program titled “One Person’s Trash is Another Person’s Tony Award,” I learned something fascinating. The show’s set designer, Donyale Werle, believes in using recycled and sustainable materials in her work. As a dedicated member of the Broadway Green Alliance, she tries to avoid the usual practice of building a complex set out of durable materials and then simply trashing it when a show is over. The highlight of the design for Peter and the Starcatcher is an old-fashioned gilt proscenium arch that frames the stage. True to her belief in re-purposing stuff that would otherwise end up in landfills, Werle has decorated her arch with cast-off materials collected with help from the alliance: 3500 used corks; 800 bottle caps; 300 pieces of plastic silverware; along with countless discarded kitchen utensils, broken toys, CDs, and other leavings of our throwaway culture. The same inventiveness marks the show’s costumes, especially in a colorful scene introducing Neverland’s mermaids, whose costumes feature old tablecloths, sponges, metal scouring pads, and hilariously strategic vegetable steamers.

The recycling of everyday objects into theatre sets and costumes appeals to me as someone who cares about our environment. But it also intrigues me – as a former Roger Corman person – because I well remember how Roger’s fundamental cheapness helped make adaptative re-use something of a mantra among his employees. If you worked for Roger, at either New World Pictures or Concorde-New Horizons, you knew all about re-using old scripts, old footage, and sometimes old actors. (Our casting director was well aware that once-famous thespians could be hired cheap for major roles because they no longer had their old box-office cachet. That’s how we got F. Murray Abraham, winner of the Best Actor Oscar for Amadeus, to star in our Dillinger and Capone, and the legendary Ray Walston to take a featured role in Saturday the 14th Strikes Back ).

Roger was especially keen on recycling sets instead of scrapping them to build something new. In 1989, when writer-director Howard Cohen was visiting the Concorde lot in Venice, California, he saw an exterior set of a medieval castle, which had just been used for some low-budget sword-and-sorcery extravaganza. Inside the studio was an ultra-modern science lab that had played a role in a science-fiction thriller. It was a lightbulb moment. Howard announced to Roger his idea for a time-travel film that would put both sets to work. That’s how The Time Trackerswas born. And Roger has also tried making two films simultaneously on the same set, one shot in the daytime and one after-hours. But that’s a story for another day.

Published on January 14, 2014 14:14

January 10, 2014

"Mary Poppins": Flying into the National Film Registry

I have a hunch that Saving Mr. Banks is not going to be inducted into the National Film Registry anytime soon. Not that I didn’t enjoy it, especially the acerbic but layered performance by Emma Thompson. She certainly made me want to know more about P.L. Travers, a woman who apparently brought her own all-too-real backstory to her timeless fantasy creation, Mary Poppins. But the endearing film from Disney, featuring Uncle Walt genially twisting Travers’ arm in order to get her flying nanny onscreen, is probably too slight (and too self-congratulatory) to live on. The flashbacks, though beautifully wrought, didn’t entirely convince me. And the day-to-day glimpses of the pre-production process -- involving screenwriter Don DaGradi and the musical Sherman brothers – were candy-coated, no question. I must admit, though, that for a Mary Poppins fan like me, it was wonderful to relive the evolution of those timeless tunes, even if what I was seeing on screen added a spoonful of sugar to the act of artistic collaboration.

I mention the National Film Registry here because the end of 2013 brought the annual announcement of new inductees. The twenty-five-year-old Registry, sponsored by the Library of Congress, includes American-made films deemed “culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant” enough to warrant preservation in the library’s archives. The 25 films chosen are always an eclectic lot, including Hollywood hits, tough-minded documentaries, obscure art films, and even home movies that have something important to say about the American past. Highlights of the 2013 list include Gilda (film noir at its finest), along with The Quiet Man (a rare John Wayne comedy, directed by John Ford), and Forbidden Planet (a sci-fi classic imaginatively based on Shakespeare’s The Tempest). The Magnificent Seven and Pulp Fiction made the list too, as did Michael Moore’s controversial Roger and Me. Among the silent films inducted, one stand-out is Daughter of Dawn, a recently discovered 1920 love story performed by an all Native-American cast. There’s also a collection of films featuring early Martha Graham dance performances, as well as The Hole, John and Faith Hubley’s 1962 Oscar-winning animated meditation on the threat of nuclear catastrophe.

As always, there were several films whose inclusion thrilled me on a personal level. I was delighted to see Mary Poppins on the list, both because of its artistry (especially its brilliant blend of animation and live action) and because it meant so much to me years ago. When I was a high school senior, my friends and I saw this movie multiple times. I think we realized that we were trembling on the brink of adulthood. Mary Poppins allowed us to briefly hold back time and revel in the innocence that would soon no longer be ours.

On the other hand, Mike Nichols’ brilliant screen adaptation of Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? introduced us young souls to the world of grown-ups in the most dramatic way possible. And as someone who appreciates the unabashed humanism of Stanley Kramer’s output, I was happy to see recognition for Judgment at Nuremberg, which takes to heart the moral issues raised by the rise and fall of Nazism.

Then there’s “The Lunch Date,” a 1989 student film by Adam Davidson that in ten minutes (and on a very low budget) manages to say a great deal about race and class. The filmmaker is the son of L.A. theatre legend Gordon Davidson and his publicist-wife Judi, who’s a friend. I tip my hat to the Davidsons. And a New Year salute to parents of talented children who much too rarely get the recognition they deserve. All hail! (See below, and enjoy!)

(P.S. Steve Carver, the director-turned-photographer who's been saluted on this site, is announcing a campaign to help support his new book, UNSUNG HEROES & VILLAINS OF THE SILVER SCREEN: Western Portraits of Great Character Actors. Horst Buchholtz, featured in new National Film Registry inductee The Magnificent Seven, is one of Steve's subjects.)

Published on January 10, 2014 12:12

January 7, 2014

The Great Wolf of Wall Street (or Chicanery is the Father of Invention)

Leonardo DiCaprio has had a big year. In spring he starred in Baz Luhrmann’s reimagining of the classic F. Scott Fitzgerald novel, The Great Gatsby. Now he’s playing the title character in Martin Scorsese’s latest, The Wolf of Wall Street. The roles are hardly identical, but there are some fascinating areas of overlap.

Starting out as a non-descript North Dakotan lacking both fame and fortune, Fitzgerald’s James Gatz reinvents himself as Jay Gatsby, a fabulously wealthy financier who reigns over a palatial spread on Long Island. When it comes to money, he seems to have the Midas touch, but his fancy cars and fancier parties (not to mention that pile of exquisite shirts) exist chiefly to impress Daisy, the lost love of his youth. He’s apparently done his share of underhanded deals, but at base he’s a thoroughgoing romantic. Money, for him, is simply a way to get the girl.

In The Wolf of Wall Street, adapted (apparently with a fair degree of accuracy) from the memoirs of stock-market hustler Jordan Belfort, money itself is the prize, and not simply the means to an end. Money buys girls (lots of them), as well as booze, drugs, costly toys, and -- above all -- power. I see the Jordan Belfort character as someone who gets high on living life at the expense of others. To feed his various urges, he is in a constant state of self-invention, which is why he’s so brilliant on the telephone, telling suckers exactly what they want to hear.

Another current movie about re-invention of the illicit kind is of course American Hustle. David O. Russell’s darkly funny film, loosely based on the Abscam Scandal of the 1980s, resembles The Wolf of Wall Streetin that it is all about the pleasures and the profits that come from conning the unwary. I can’t resist seeing this movie’s stellar cast as engaged in personal self-inventions onscreen. Christian Bale (a wiry Bostonian in Russell’s The Fighter) metamorphoses here into a chubby New Yawker with an elaborate comb-over. The wholesome, winsome Amy Adams turns into a sexpot (boy, do her necklines plunge!) of uncertain nationality. Bradley Cooper, once People Magazine’s Sexiest Man Alive, appears in American Hustle as a goofy FBI agent with a bad perm. The protean Jennifer Lawrence is lightyears removed from her tough-girl role as Katniss Everdeen in The Hunger Games. And, in a surprise cameo, one of Hollywood’s greatest actors does something completely unexpected.

If The Wolf of Wall Street is compared to American Hustle, it seems far less comic, and far more ferocious. Those who’ve seen both films will understand what I mean when I say that Russell’s film is all about hair, and Scorsese’s is all about skin. I appreciated them both, but give the nod to The Wolf of Wall Street because of Scorsese’s absolute mastery of the film medium. I understand why his work here is controversial, but can’t grasp why some feel he’s glamorizing wrongdoing. By the end of The Wolf of Wall Street, DiCaprio’s character is clearly not having fun. Why can’t people see that this is, at base, a morality tale?

It is also a film that’s three hours long. Though I didn’t feel anything was extraneous, there’s no question that 180 minutes is a lengthy sit. That’s why a new app highlighted in the L.A. Times may have its uses. Www.RunPee.com advises the conscientious moviegoer of the best time to take a bathroom break, then tells you what you missed. For us aging Baby Boomers at the multiplex, this might be just the ticket.

Published on January 07, 2014 09:25

January 3, 2014

The Rose Parade: Starting 2014 the SoCal Way

Like all good Southern Californians, I spent the first morning of New Year’s Day 2014 glued to my television set. The Rose Parade has been a January tradition for 125 years. I’m not nearly that old, but I’ve been watching the floats roll down Pasadena’s Colorado Blvd. ever since my parents bought their first Zenith. The parade represents a special kind of showbiz, one that combines sophisticated technology with the immediacy of a live event. In its razzle-dazzle beauty, it’s SoCal all the way.

The Rose Parade was founded by members of the Valley Hunt Club. They sought to promote local real estate to East Coasters who might be attracted by the San Gabriel Valley’s mild climate and genteel cultural attractions. So they paraded in horse-drawn buggies bedecked with flowers, in imitation of the rose festival in Nice, and then staged a football match. (Later came chariot races, before the Rose Bowl game was established as one of January’s premier college sports competitions.)

Spectators gathered to see the early parades. Starting in 1900, newsreel footage allowed audiences throughout the U.S. to participate vicariously. By 1947, the parade was being broadcast on a newfangled contraption called television. A few years later, the roses burst into living color. Then came the Sixties, when satellites delivered the Rose Parade to viewers across the globe. By now I suspect it’s been seen by astronauts floating through space.

Speaking of outer space, it was a popular motif on 2014 Rose Parade floats. This year’s parade, whose theme was “Dreams Come True,” featured flower-covered spacecraft, a space shuttle, and some oversized Little Green Men who spectacularly dismounted from their vehicle to explore earth’s surface. But movies were not forgotten. The float representing the city of Los Angeles paid tribute to our local entertainment industry by showcasing Universal Studios, as well as Hollywood’s Chinese Theater. Not to be outdone, the city of Burbank recognized its own role as a film production hub by depicting a movie set, on which a Perils of Pauline-style heroine is tied to the tracks in the path of an ongoing train, as an old-fashioned camera records the action. (Hollywood’s Garry Marshall sat in the director’s chair, waving to the crowds.)

If viewers of yesterday’s parade saw plenty of floral spaceships (along with several teddy bears and many cute dogs), they also saw some communications systems that would have seemed impossible even a few years back. The parade opened with a 274-foot-long entry from American Honda, depicting a string of futuristic vehicles. One boasted a long-armed camera that scanned the crowds along the parade route, then turned them into “virtual riders” on two enormous traveling video screens.

If Honda’s presence in the parade signified a triumph for high-tech mass communications, the folks in the KTLA broadcast booth were a throwback to a much earlier era. Savvy Californians know better than to watch Rose Parade coverage on the national networks, which are dominated by commercials and by hosts with little knowledge of parade history. Instead we tune in to folksy Bob Eubanks and Stephanie Edwards, who’ve been broadcasting the parade on KTLA for the past thirty years. They’re hardly youngsters: former game-show host Eubanks was born in 1938, and perky Stephanie in 1943. Stephanie’s age became a topic of much discussion a few years back when KTLA replaced her in the booth with a much younger (and more ethnic) female. Poor Stephanie was relegated to doing commentary from a grandstand, smiling gamely while getting drenched in a rare New Year’s rain shower. But now Stephanie’s back where she belongs. The tradition continues.

Published on January 03, 2014 11:40

December 31, 2013

Peter O’Toole – How to Steal a Million (Hearts)

In the final few weeks of 2013, film fans lost some larger-than-life stars. The most celebrated, of course, was Peter O’Toole, who burst onto the screen in 1962 as David Lean’s Lawrence of Arabia. Then, having played to perfection a famously enigmatic warrior-philosopher, he moved on to other roles that bore a tragic and literary stamp, like the title character in Joseph Conrad’s Lord Jim. He played kings aplenty, including England’s Henry II in both Becket (opposite Richard Burton) and The Lion in Winter (where he colorfully sparred with Queen Eleanor of Aquitaine, as imperiously portrayed by Katharine Hepburn). And he also played cheeky commoners who considered themselves ripe for kingly privilege: a movie director in The Stunt Man; a matinee idol in My Favorite Year; a pompous restaurant critic in Ratatouille. In The Ruling Class he topped himself, as a member of the House of Lords who becomes convinced he is Jesus Christ.

O’Toole’s real-life propensity for living large made him perfect casting in such grandiose roles. But he could also play more humble fellows. A musical version of Goodbye, Mr. Chips would seem an unlikely vehicle for him, but he made the modest British schoolmaster both convincing and appealing. (His singing wasn’t so great, but the forgettable Leslie Bricusse song score hardly deserved better.) My own personal favorite O’Toole film is a dotty little romantic farce from 1966 called How to Steal a Million. It’s about a very nice young lady (Audrey Hepburn) who for complicated reasons needs to steal a priceless statue, the Cellini Venus, from a Paris museum. Enter O’Toole as a professional thief – or is he? With such veteran farceurs as Hugh Griffith, Eli Wallach, and Charles Boyer filling out the cast, it’s a light and charming entertainment.

It’s sad, of course, that O’Toole never won the Oscar he so richly deserved. But he outlasted all of his drinking buddies (Richard Burton and Oliver Reed among them) and gave us some wonderful hours at the movies.

Joan Fontaine was known for playing the second Mrs. de Winter in Alfred Hitchcock’s Oscar-winning Rebecca. She won her own Oscar for another Hitchcock film, Suspicion. The delicate blonde – a true English rose – specialized in roles that played up her air of genteel vulnerability. (She makes a dramatic contrast to the virile Burt Lancaster in a taut little 1948 thriller with an unlikely title: Kiss the Blood Off My Hands.) But Fontaine was most famous for her life-long feud with her equally stellar sister, Olivia de Havilland. Fontaine always claimed she was the victim of her elder sib’s unrelenting cruelty. But I wonder. Did the English rose have a few thorns of her own?

Finally, I’ve got to mention Tom Laughlin, not exactly a great actor, but one who made his mark on Hollywood during the heyday of the Counterculture. His Billy Jack character, first introduced in 1967’s Born Losers, is an ex-Green Beret with exotic martial arts skills and a rather violent commitment to pacifism. By 1971’s Billy Jack, Laughlin and wife Delores Taylor had become their own cottage industry: he directed the two of them in a screenplay they wrote together, and the money came rolling in. The rather stiff but dramatic story has our hero saving wild horses from slaughter and protecting the kids in a desert “freedom school.” More Billy Jack movies followed, and soon my boss Roger Corman was instructing rising young director Jonathan Demme to concoct his own Billy Jack clone. And that’s how our Fighting Mad was born.

Peter O’Toole, Joan Fontaine, Tom Laughlin – may they all rest in peace.

Published on December 31, 2013 09:31

December 26, 2013

Stallone and De Niro Celebrate Boxing Day

No, your eyes aren’t deceiving you. The two codgers on the billboards, the ones wearing striped trunks and boxing gloves, really are Robert De Niro and Sylvester Stallone. Their new film, Grudge Match, opened yesterday. But December 26, the day after Christmas, is celebrated in British Commonwealth nations as a time when workers enjoy a well-deserved holiday break. The Brits call it “Boxing Day,” perhaps because this was traditionally when appreciative aristocrats gave gifts to their loyal servants. At any rate, Boxing Day seems a fitting moment to discuss a comedy about two pugilistic rivals who get back in the ring to settle a thirty-year-old score.

I’m not much inclined to see Grudge Match. But I’ve certainly followed the careers of both Stallone and De Niro. I caught Stallone in his first big role as a Brooklyn gang member in a small 1974 indie, The Lords of Flatbush, and cheered his breakout performance in Rocky, for which he also wrote the script. Though I can’t pretend to be acquainted with Stallone’s full array of action flicks, there’s no question in my mind that he’s an indelible figure in Hollywood, one who’s created for himself a unique persona. When I think of De Niro, I remember his dangerous unpredictability in such dark films as The Godfather Part II, The Deer Hunter, and This Boy’s Life. Martin Scorsese entrusted him with powerful roles in some of his most gripping work: Taxi Driver, Raging Bull, Goodfellas, Cape Fear. The list goes on and on, though he’s recently developed his funny side in goofy comedies like Analyze This and Meet the Parents.

One fact ties these two actors together, and it’s not that they’ve both played boxers. Both Stallone and De Niro got major career boosts through Roger Corman movies. Stallone, then New York-based, was cast by Steve Carver as the very deadly Frank Nitti in Capone, a co-production of New World Pictures and Twentieth-Century Fox, starring Ben Gazzara in the title role. On Steve’s recommendation to Paul Bartel, Stallone nabbed the part of a lethal racecar driver, Machine Gun Joe Viterbo, in a Corman-produced dark comedy that has gone on to become a cult classic. Of course I’m talking about Death Race 2000. I vividly remember the day in 1974 that several of us involved with the production were eating lunch in a dim coffee shop. Suddenly a large figure dressed all in black loomed over our table. It was Stallone, come to greet his future director.

As for De Niro, he was directed by Roger Corman himself in 1970’s Bloody Mama, a lurid little film about a Depression-era crime spree. Oscar-winner Shelley Winters, who played a fictionalized Ma Barker, recommended to Roger some New York Actors Studio types for the roles of her highly perverse sons and lovers. The cast included Don Stroud (for whom both Roger and Shelley had the highest hopes) as well as a young Bruce Dern. De Niro became Lloyd Barker, a hopeless drug addict. This was three years before he gained national attention as a dying baseball catcher in Bang the Drum Slowlyand then as Mean Streets’ volatile Johnny Boy.

When he made Mean Streets, Martin Scorsese had just finished directing Box Car Bertha for Roger Corman. Hoping to film his own highly personal New York story, he turned to Roger for financing. Roger’s demand that he transform Mean Streets into a blaxploitation flick made Scorsese look elsewhere for help. Which is why this quintessentially New York film was shot on the mean streets of Los Angeles. But that’s a story for 2014.

Dedicated to Elena Allen, who provided inspiration.

Published on December 26, 2013 10:51

December 24, 2013

"Inside Llewyn Davis": The Cat Came Back

You can count on two things in a Coen Brothers movie: misery and music. The plot of The Big Lebowski involves kidnapping and extortion, set against some classic rock, an old cowboy tune (“Tumbling Tumbleweeds”), and a production number inspired by Busby Berkeley. A Serious Man -- a contemporary riff on the Book of Job – climaxes when an old-world rabbi offers as Talmudic wisdom the lyrics of Jefferson Airplane’s “Somebody to Love.” In O Brother, Where Art Thou?, some escaped convicts dodge a lynching and other disasters, while posing as a bluegrass group, the Soggy Mountain Boys. Though their theme song is “Man of Constant Sorrow,” there’s nothing much sorrowful about O Brother. Instead, it’s a rollicking romp, in which misery (a flood of epic proportions, for instance) is transformed into exaltation.

Perhaps the exuberant optimism of O Brother, Where Art Thou? stems from the fact that it’s set among true believers who have faith in God’s rewards, whether in this life or the next one. But in jumping from the Depression-era South of O Brother to Kennedy-era Greenwich Village for Inside Llewyn Davis, the Coens have given themselves a more morose set of characters. True, as Joel and Ethan told Fresh Air’s Terry Gross, the young Baby Boomers who launched the folk music craze started by immersing themselves in Southern roots music, of the sort that O Brother celebrates. But such troubadours as Bob Dylan brought to the folk revival not the religious convictions of the Deep South but rather a strong determination to get outside the middle-class world in which they grew up.

There’s some fun in Inside Llewyn Davis, notably a goofy novelty song called “Please, Mr. Kennedy” in which an astronaut pleads not to be sent into space. It’s amusing too seeing the Coens deftly parody some of the most celebrated singers of the pre-Dylan era, including Tom Paxton, the Clancy Brothers in their Irish fisherman sweaters, and the desperately sincere Peter, Paul and Mary. But the focus is on Llewyn Davis, who has something of the career of the legendary Dave Van Ronk but hardly his look or his gravelly sound. As played by Oscar Isaac, Llewyn is a sweet-voiced but hopelessly hangdog fellow who has a talent for pissing off his friends, the few he has left. He’s at the other end of the spectrum from George Clooney’s cocky charmer in O Brother: this is a man with real musical gifts, but one who creates gloom wherever he goes. We first meet him singing a somber ditty that begins “Hang me, oh hang me, I’ll be dead and gone.” Most of his other songs have something to do with farewells and partings. When, midway through the film, he has what seems a golden opportunity to dazzle an important impresario, he chooses a dirge about the death of Henry VIII’s Queen Jane. What fun!

While staving off meaningful human contact, Llewyn finds himself stuck with a big orange cat that has the annoying habit of slipping away when he most needs to corral it. Filmmakers know that cats can’t really be trained. The best you can do is have several on hand: the lethargic one willing to be carried around, the jumpy one inclined to run off, and so forth. In some scenes, the cat was actually attached to Oscar Isaac with a hidden wire. If he was ever a cat-fancier, those days are over.

I’ve just been reading about the making of Breakfast at Tiffany’s. That classic film contained a runaway orange cat too. Did Holly Golightly’s Cat run straight to Llewyn Davis?

Published on December 24, 2013 12:39

December 20, 2013

“'Good Evening, Mr. and Mrs. America, and All the Ships at Sea” -- Walter Winchell Signs Off

The recent obits for actress Jane Kean all noted that she played Trixie Norton in the Jackie Gleason Show’s Honeymooners episodes from 1966 to 1970. Few of them mentioned that in the early 1950s she was the protégée and mistress of America’s most powerful newspaperman, Walter Winchell.

Winchell spotted the petite blonde at New York’s Copacabana, where she was appearing in a sister-act that featured comedy and music. From the first he was smitten with both Kean sisters, inviting them to come along as he cruised Manhattan’s byways in the wee small hours, checking out police calls. Through his syndicated columns and his hugely popular radio broadcast he spread the word about their charms. One result: in 1955 Jane and Betty Kean enjoyed a five-month run as headliners in a Broadway extravaganza called Ankles Away. But all the attention quickly stopped when Jane insisted that Walter (thirty years her senior) divorce his wife. Winchell may not have had much use for domesticity, but he regarded as sacred his public reputation as a family man.

All this and much more I learned through Neal Gabler’s definitive Winchell: Gossip, Power and the Culture of Celebrity. Gabler made me see that Winchell’s personal saga is also the story of twentieth-century America. In the 1920s, when the young ex-hoofer’s Broadway column first began, he showed the rising middle-classes just how celebrity gossip could cut the rich and famous down to size. His slangy use of colloquial English, laden with lively innuendo, changed journalism forever. In the 1930s he rode the crest of the radio wave, attracting listeners from sea to shining sea. (Gabler says that at the height of his fame, 50 million Americans – out of a population of 75 million – either listened to his broadcasts or read his daily columns.)

Given his craving for power at a time when world events were shaking up everyone’s lives, it’s no surprise that Winchell soon turned political. Before and during World War II, he was an unabashed booster of Franklin Delano Roosevelt, using his own bully pulpit to push the Roosevelt agenda, often with the covert help of FDR’s inner circle. But his close personal ties with J. Edgar Hoover led him, after the war, into a fierce anti-communism that made him an early ally of Senator Joseph McCarthy.

Winchell’s political about-face – combined with the rise of television and a number of other factors – made him seem far less attractive to his fan base as the Fifties gave way to the Sixties. Gabler vividly details a 1951 run-in with black entertainer Josephine Baker, whose apparent mistreatment at Winchell’s beloved Stork Club led him to make grotesque accusations about her political leanings. Though this ugly episode, in Gabler’s eyes, was the beginning of the end for Winchell, he tenaciously hung on, even while a Hollywood drama, Sweet Smell of Success, splashed onscreen the dark side of his image. Starting in 1959, he even became a TV star of sorts, adding an idiosyncratic rat-a-tat narration to a popular series based on FBI heroics, The Untouchables.

Several twentieth-century songs, including Mel Brooks’ “I Want to be a Producer,” allude to the great coup of getting one’s name in Winchell’s column. But as that column sank in importance to his fellow Americans, the man himself increasingly seemed to be living in a world of his own. His long-suffering wife passed away; his son and namesake committed suicide. When he himself died in 1972 -- aged 74 but looking much older – he went out not with a bang but with a whimper. Mr. and Mrs. America didn’t much care.

Published on December 20, 2013 13:51

December 17, 2013

The Sound of Music: The Sound of One Hand Clapping?

Two weeks ago, America’s TV sets were alive with the sound of music. Or something like that. At any rate, the Twittersphere was alive with the sound of big, fat Bronx cheers. Professional critics were not alone in proclaiming NBC’s live musical version of the beloved singing-nun story one of their LEAST favorite things.

As for me, I didn’t see it. True, the notion of a live stage musical playing itself out in my family-room transported me back to the lovely days of my TV-watching childhood (Julie Andrews as Rodgers and Hammerstein’s Cinderella! Mary Martin re-creating her stage performance as Peter Pan!) Still, I really wasn’t enticed by the prospect of watching American Idol winner Carrie Underwood try on Maria’s wimple. Frankly, an evening in the company of brown paper packages tied up with strings sounded like more fun to me.

Lord knows, it may be heresy (at least among several members of my immediate family), but I was never a devotee of the blockbuster 1965 film either. I know there are those who consider the casting of Julie Andrews and Christopher Plummer divinely inspired, and regard each of the Von Trapp tykes as a morsel of perfection. Yes, the Alpine scenery was undeniably glorious. I appreciated such touches as the casting of a leading lady who actually COULD sing (take that, Audrey Hepburn!) and the on-screen appearance of Marnie Nixon, who had famously dubbed the lilting soprano voices of Hepburn in My Fair Ladyand Natalie Wood in West Side Story. Since Nixon wasn’t needed to stand in, vocally speaking, for the movie’s heroine, it was splendid that we finally got to see what she looked like, though a nun’s habit pretty much concealed her from view.

But even in those days, I was somewhat of a contrarian. And one reason I couldn’t fully adore the movie is that I treasured the memory of seeing The Sound of Music onstage. At L.A.’s old, barnlike Philharmonic Auditorium, I applauded Florence Henderson and the rest of the touring company. But it was Mary Martin who starred on the cast album that my family played over and over. Those were the days when any middle-class family aspiring to culture boned up on Broadway’s latest hits. We owned the LPs of The Music Man, Fiddler on the Roof, and the entire Rodgers and Hammerstein output, and we knew every word of every song. No wonder I take Sound of Music so personally.

Much has been made of the death last week of Eleanor Parker, who played the aristocratic fiancée of Baron von Trapp in the 1965 film. (Some wags have insisted it was Carrie Underwood’s TV performance that killed her.) But fans of the movie rarely notice that two Rodgers and Hammerstein songs involving Parker’s character didn’t make it from stage to screen. Both “How Can Love Survive?” and “No Way to Stop It” are cynical ditties sung by the Baron’s sophisticated friends, who are all too ready to accept a Nazi takeover, so long as they can enjoy their own luxurious lives in peace. I loved these songs, because they added to the stage musical a spoonful of vinegar that helped the treacle go down. In the movie version, though, the songs were cut.

Mary Martin was doubtless too old for the screen adaptation of Sound of Music and I can’t deny Julie Andrews’ fresh appeal. Israeli folksinger Theodore Bikel, who played the original Baron von Trapp, has had a curious movie career, playing men of widely varying nationalities. How many know he was Oscar-nominated for The Defiant Ones?

Published on December 17, 2013 09:11

December 13, 2013

Dana Andrews -- The Best Years of His Life

With Dana Andrews, Carl Rollyson hit the jackpot. Carl, like all who devote their lives to exploring the lives of others, knows how hard it can be is to contend with the family of a biographical subject. Some relatives are resistant, wanting the family secrets to remain secret. Some want to take control, insisting that their version of events is the only possible interpretation. There’s a grim joke among biographers forced to deal with a deceased subject’s next of kin: “First kill the widow.”

With Dana Andrews, Carl Rollyson hit the jackpot. Carl, like all who devote their lives to exploring the lives of others, knows how hard it can be is to contend with the family of a biographical subject. Some relatives are resistant, wanting the family secrets to remain secret. Some want to take control, insisting that their version of events is the only possible interpretation. There’s a grim joke among biographers forced to deal with a deceased subject’s next of kin: “First kill the widow.” But occasionally you get lucky. Carl was approached by Susan Andrews, Dana’s daughter, because she and her siblings were seeking a fuller understanding of their famous father. They had letters, memorabilia, and the diary of a man who had always held firmly onto his past. They were happy to be interviewed, but would not interfere with Carl’s conclusions. It was the perfect opportunity to take a closer look at an actor whom Carl had long admired. The book was published in 2012. Carl calls it Dana Andrews: Hollywood Enigma.

As the title suggests, Dana Andrews was something of a mystery man. Not for him the flamboyant public life of most stars. He and his family lived well, in suburban Toluca Lake, but he vigorously shielded his wife and kids (as well as himself) from the Hollywood social circuit, with its retinue of eager reporters trolling for gossip. His resistance to glitz and glamour partly stemmed from his upbringing, as one of 13 children born to a strait-laced Texas preacher and his wife. His early years as a cog in the Hollywood studio system also helped shape his attitude. While a contract player (1938-1941) under the imperious Samuel Goldwyn, he was expected to squire starlets around town, in order to generate publicity. Though he badly wanted to wed his sweetheart, Mary Todd, he was forced to seek Goldwyn’s permission before heading for the altar.

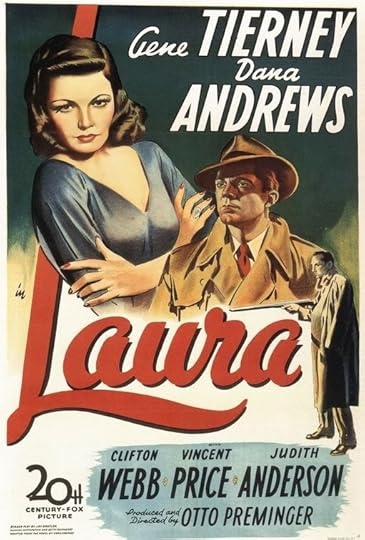

As an actor, Dana Andrews was known for portraying common men who reveal an uncommon nobility. His best performances are subtle ones, marked by heroic restraint. Carl Rollyson, once an aspiring actor himself, is at his best when dissecting Andrews’ pivotal role as a lynching victim in 1943’s The Ox-Bow Incident. It was Laura (1944) that shot him to stardom, as the police detective who’s not quite as matter-of-fact as he first seems. But the performance I cherish can be found in 1947’s big Oscar winner, The Best Years of Our Lives. This film about military draftees readjusting to civilian life meant a great deal to my parents – and, I suspect, to many whose lives were touched by the upheavals of World War II. At the Oscar ceremony, Frederic March was named Best Actor for portraying a middle-aged banker whose values shift after his homecoming. And Harold Russell, a first-time actor who’d lost both hands in a military training exercise, won a Best Supporting Actor statuette, while also copping an honorary award for inspiring his fellow veterans. Their performances are undeniably poignant, but Andrews (as a war hero brought down to earth by his lowly civilian status) is the glue that holds the story together. He received no Oscar love then, nor for any other role.

It’s startling to read about Dana Andrews’ problems with alcohol, which ultimately shortened a splendid career. Carl views drink as Andrews’ way of coping with a world in which he felt uncomfortable. In 1972, though, he licked his demons, then bravely filmed a public service announcement owning up to his alcoholism and urging drunk drivers to stay off the road. As always, he was a class act.

As a biographer myself, I applaud Carl Rollyson’s many achievements. And I can’t resist mentioning a coup of my own: getting an unexpected rave from a New York Times reviewer who favorably compared my Roger Corman bio to a new Corman coffee-table book costing twice as much.

Published on December 13, 2013 10:10

Beverly in Movieland

I write twice weekly, covering topics relating to movies, moviemaking, and growing up Hollywood-adjacent. I believe that movies can change lives, and I'm always happy to hear from readers who'd like t

I write twice weekly, covering topics relating to movies, moviemaking, and growing up Hollywood-adjacent. I believe that movies can change lives, and I'm always happy to hear from readers who'd like to discuss that point.

...more

- Beverly Gray's profile

- 10 followers