Beverly Gray's Blog: Beverly in Movieland, page 123

February 18, 2014

The Marvelous Menace of Lee Marvin

February 19 would have been Lee Marvin’s 90thbirthday. So says Dwayne Epstein, who ought to know, because he’s the author of an authoritative new biography, Lee Marvin: Point Blank.

Dwayne has asked me to dedicate today’s Beverly in Movieland blog post to his favorite subject, and I’ve been easily persuaded. Dwayne’s a deserving guy, and besides, I wouldn’t want the ghost of Lee Marvin coming back to beat me up, or dangle me from an upper-story window (as he did with poor Angie Dickinson in The Killers).

Dwayne insists Lee Marvin ushered in a motion picture era that’s still with us, what he calls the Cinema of Violence. A look at the many highlights of Marvin’s career – ranging from Bad Day at Black Rock to The Wild One to The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance to (yes) Point Blank – reveals a wide range of tough-guy roles. Even Marvin’s Oscar-winning performance in 1965’s Cat Ballou, though wildly comic, casts him as a mismatched pair of gunslingers. Marvin’s massive physique, coupled with his unmistakable whiskey croak, immediately signifies him as man who courts danger and meets it halfway.

In Dwayne’s telling, you have to look to Marvin’s own biography for the source of his dark power. There’s an odd episode that occurred well before he was born: his father’s beloved uncle and guardian, on an arctic expedition with the legendary Commander Peary, was murdered under mysterious circumstances, though for years the deed was hushed up. Says Dwayne, “The devastating effect this had on [Marvin’s father] was incalculable. For the rest of his days he kept his most vulnerable emotions in check as a result of this primal act. In contrast his son, a recognized international film icon, would spend his adult life exploring the emotional impact of violence, and its effect on the human experience.”

As a growing boy, Marvin constantly butted heads with his father and with school authorities. But the prime shaper of his own life was his experience in World War II. He left high school in 1942 to enlist in the U.S. Marine Corps, and faced the enemy close-up on Saipan, during a battle in which most of his unit was killed. He himself was shot in the buttocks: later, on a hospital ship, he checked his wallet and discovered “a gaping, blood-soaked hole through a photo of his entire family.” He also brought away from the battlefield a letter he took off the body of a dead Japanese soldier. When he had it translated, he was startled to find that the soldier’s thoughts about war and life back home were hardly different from his own. The emotions this letter roused in him later contributed to a World War II film he made in 1968 opposite the great Toshiro Mifune, Hell in the Pacific.

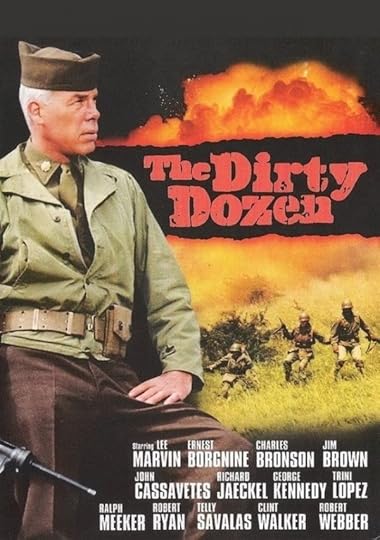

Hell in the Pacific was hardly the first war film – or the last – in which he starred. In Stanley Kramer’s Eight Iron Men, he taught the rest of the cast authentic military behavior, including how to die convincingly. Much later, he led the cast of such classics as The Dirty Dozen and Sam Fuller’s The Big Red One. According to Dwayne, Marvin once told a friend that he was a trained killer with an unquenchable need for violence. He’d go into barrooms and deliberately pick a fight, coming home with bruises and black eyes. The current diagnosis would be PTSD: because Lee Marvin experienced violence for real, he brought that reality onto the world’s movie screens. Quentin Tarantino is only one of today’s filmmakers who identify themselves as Sons of Lee.

Happy birthday to Jeff, who was born one day before Lee Marvin, and a whole lot of years later. May Jeff’s life be far more peaceful than Marvin’s was.

Published on February 18, 2014 11:58

February 14, 2014

A Tasty Treat for Valentine’s Day (if you like zombies)

Zombie Butterscotch Kiss -- sounds perfect for Valentine’s Day, right? Unless, of course, you’re not so sure about zombies. I mention this title, because it’s the name of a project by a former student of mine. She completed a course I offered last fall through the screenwriting division of UCLA Extension’s Writers’ Program. This particular course is an advanced workshop called “1-on-1 Feature Film Rewrite.” It promises 12 enrollees (chosen for the quality of their script submissions) serious personal attention as they strive to bring their screenplays to the highest possible level.

Though I’ve long been a classroom teacher, I’ve taught exclusively online for the last seven years. It still surprises me how an instructor and a student can develop real rapport over the Internet, without ever coming face to face. (For one thing, online communication effectively removes the blowhards who tend to dominate classroom discussions, but who are generally more noisy than talented.) An online class, in fact, is ideal for situations where each student expects intense personal feedback.

Another thing about online courses: they attract enrollees from all over the world. My class has contained some remarkable aspiring writers from Greece, China, Mexico, and Canada. One of my all-time favorites was a Jesuit priest in Dublin. He was depicting a missionary’s life in Africa, and his handling of a scene with sexual implications was definitely unique. This past fall, I had not one but two talented Aussies on my roster. They didn’t know one another (hey, it’s a big country!), but I helped them connect, and also enjoyed working with them individually.

So I’m finally back to Zombie Butterscotch Kiss. It’s the brainchild (so to speak) of Judith Duncan, who makes her home in Sydney. The ten years she spent doing improv theatre led her to study writing. Recently she earned an Honors Degree in Media Arts at Sydney’s University of Technology, and – through the wonders of cyberspace -- also completed UCLA’s Professional Program in Screenwriting. Now she earns a living as a receptionist (“great training for filmmaking, as I problem-solve all day”), while also teaching “Writing Dr. Who” through the Open Program of the National Institute of Dramatic Art, which happens to be Cate Blanchett’s alma mater.

Judith’s original coming-of-age drama, Zombie Butterscotch Kiss, attracted attention in a horror screenplay competition held by the Australian Writers’ Guild. Despairing of getting it produced in her homeland, she’s turned it into a novel. On the strength of her first 25 pages (which were polished in yet another UCLA Extension course) she’s been accepted into an exclusive writers’ workshop sponsored by the Djerassi Artist Colony. Trouble is – the colony is located near San Francisco, not Sydney. “My dreams being much bigger than my bank balance,” she is now in fundraising mode, and has shot three short YouTube videos in a bid to raise the money to finance her travels. Says Judith, “Roger Corman would have been proud of me. I wrote the scripts, we shot them all in one day in December down at the local park, with four crew including my neighbor, in-camera sound, and my sister did the catering.”

Here’s a link to Judith’s crowdfunding site, which will be up until March 27. I’ve also promised director Steve Carver I’d remind readers of his unique Unsung Heroes and Villains of the Silver Screen photography project, which is also seeking public support. And anyone interested in my upcoming UCLA Extension course should write to Chae Ko at cko@uclaextension.edu or phone 310-206-2612.

Enough commercials. Meanwhile, enjoy Zombie Butterscotch Kiss. And Happy Valentine’s Day!

Published on February 14, 2014 10:54

February 11, 2014

Alone at the Movies: The Medium Makes the Message

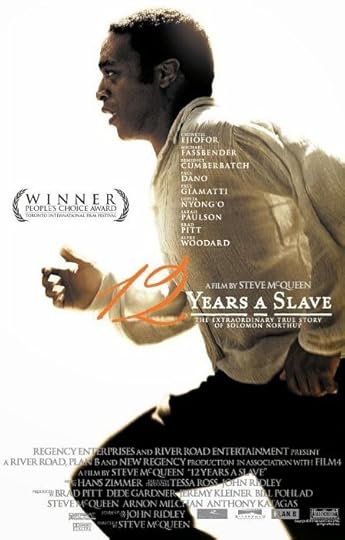

Last week I was musing about my experience in a local multiplex, watching 12 Years a Slave while trying to block out the rantings of a woman in the throes of dementia. Part of my point was that moviegoing is intended as a communal experience. Traditionally, movies are made to be seen by large groups of people, feeding off of one another’s amusement, or exaltation, or fear. Yes, it’s maddening to be disturbed by an unruly patron in the next row. But those choosing to watch a video solo, in the privacy of their homes, are missing out on something: jokes aren’t as funny and scare moments aren’t as shivery if they’re not shared.

Back in 1976, I watched a brand-new film called Rocky in a packed neighborhood theatre. During the climactic bout between Rocky and Apollo Creed, the L.A. audience was emotionally transported. In our minds we were all ringside at a live sporting event, and we were not embarrassed to cheer aloud for our hero. It was deafening in that theatre—and thrilling!

Then there was the day that I (as a young film critic) was invited to write about Teshigahara’s Woman in the Dunes. It’s a stark film about isolation and entrapment, and I saw it completely alone, sitting in the middle of an empty art house. My solitary viewing perhaps brought home the film’s lessons with special force, but I cannot think of that afternoon without a shudder.

The subject came up recently when I discussed Roger Corman with Mark Lynch, whose “Inquiry” is heard weekly on WICN (90.5 FM) in Central Massachusetts. Mark, a true movie buff, as a young man traveled from Worcester to Boston to experience William Castle’s The Tingler, complete with wired theatre seats. He’ll never forget the hysteria and the laughter greeting the moment when creature apparently springs from the screen and gets loose among the moviegoers. The crowd reaction was so intense that he never did see The Tingler’s last 10 minutes.

Since my interview, which you can check out here, I’ve discovered that Mark has thought long and hard about the effects a movie can have on a home viewer. He recalled, “I had a very bad case of the flu once (temps 104-105) and I began to watch The Harvey Girls, going in and out of awareness . . . . I began to think the film just consisted of different versions of “The Atcheson, Topeka, and the Santa Fe.” Apparently I kept dozing off and on during that one number and thought a lot of time passed. Then I kept the TV on and all the subsequent films (a film noir and some comedy) all wove themselves together into one huge disjointed film in my mind. Very uneven, but it all sort of made (feverish) sense. ‘Where's Judy Garland?’ I kept thinking, then dozing off again.”

Mark has his pet theories about comfort films, the videos that make you feel better when you’re down. No, he wouldn’t suggest Eraserhead. On his list for colds is Forbidden Planet (“I bet the Kryll had a cure for the cold”). Or maybe The Andromeda Strain (“I guess my cold could be worse”). For stress or general malaise, he advises The Seventh Seal (“It's so dark and serious, I have to feel better in comparison,” Anyway, “it's just great to wallow in Swedish misanthropy.”)

I have my own disturbing memories of trying to use movies to stave off serious illness. It didn’t exactly work, but being in a cinematic Twilight Zone at least helped pass the time.

Published on February 11, 2014 09:38

February 7, 2014

12 Years a Slave: Two Different Kinds of Chains

Just in time for Black History Month, I finally saw 12 Years a Slave. Given the film’s strong subject matter and stellar cast, I knew it was worthy of my attention. Still, a harshly realistic story about slavery in the Ante Bellum south didn’t sound like much fun.

Many moviegoers have obviously felt the same way. Though 12 Years a Slave has received strong critical response, not to mention 9 Academy Award nominations, it has racked up nowhere near the box office of its Oscar rivals, Gravity and American Hustle. What’s exciting is that any of these three very different films could win. As a group they remind me of the diverse kinds of movies that have nabbed Best Picture Oscars in the past. 12 Years a Slave is serious, sober, implicitly using the film medium to help right an old wrong. In this it feels something like Schindler’s List: cinema as history lesson. American Hustle, by contrast, is charming in its audacity. It may have vague historical implications, but mostly it’s about the twists and turns of a scam, as practiced by skillful con artists. Doesn’t that sound like 1973’s delightful Oscar winner, The Sting?

Then there’s Gravity, whose ambitions are epic in scope. In its technical mastery of the film medium on a grand scale, it falls into the category of a David Lean film, or perhaps James Cameron’s Titanic. Its underlying metaphysical questioning of man’s (or woman’s) place in the universe is of course more reminiscent of Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey. That groundbreaking film was not even nominated for Best Picture, though it won an Oscar for its visual effects and Kubrick made the Best Director short list. Alfonso Cuarón has received the Directors Guild award for Gravity, and perhaps he’ll be similarly honored come Oscar night.

In all this I haven’t said much about my personal reaction to 12 Years a Slave. I found the film well-directed, beautiful to look at, and peopled with strong actors. I’ve admired the versatile Chiwetel Ejiofor for years -- check him out as a very different kind of man in Kinky Boots! -- and there’s good work done in large roles and small. Still, 12 Years a Slave struck me as somewhat flat and dutiful. Perhaps this can be blamed on the eighteenth-century source material, but Solomon Northrup’s character seemed short on complexity, and his final release from bondage lacked the dramatic power I would have expected.

But maybe there’s a reason for my rather tepid emotional response. I saw the film during the daytime, in a multiplex much favored by senior citizens. Just before the lights dimmed, an elderly man entered, carefully shepherding a woman of his own age who seemed physically and mentally “off.” They didn’t sit near me, but soon there was no overlooking this woman’s disabilities. She began talking loudly, completely oblivious to the decorum expected of moviegoers. The man tried to shush her, as did the polite young usher who was eventually summoned. It was clear she was wrestling with dementia, and removing her for the sake of the other patrons would have been neither easy nor – come to that – humane. So I, like the others, tried hard to tune out her ranting. Still, I felt profoundly sorry for her, and for the man who was obviously trying hard to cope. The sadness of their story, unfolding a few rows away from me, effectively trumped the tale I was watching on screen.

A good thing this wasn’t Florida, where moviegoers carry loaded weapons to pay back those who disturb their concentration.

Published on February 07, 2014 10:03

February 3, 2014

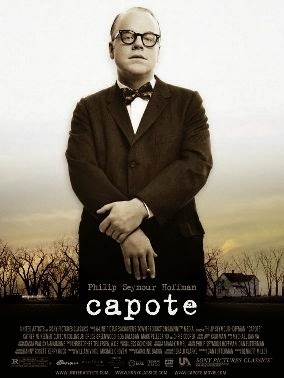

Philip Seymour Hoffman: The Death of a (Super) Salesman

The morning of the Super Bowl, I (like millions of other movie fans) was shocked to read about the death of Philip Seymour Hoffman. All signs have pointed toward a drug overdose, and I’m surprised by the depth of my own sadness and disappointment. I can shrug off the premature passing of a music legend destroyed by years of living large: immaturity and lack of impulse controls seem to go with the territory for pop idols and rock gods. I was sorry when the promising young actor River Phoenix died at 23, but I could attribute his drug abuse to an eccentric upbringing, followed by stardom at a too-young age. I felt much the same when learning of the passing of 28-year-old Heath Ledger, who seemed to have succumbed (via an accidental overdose of sleeping pills and anti-anxiety meds) to the pressures of having too much success too soon.

But Hoffman? He struck me as intelligent, mature, a grown-up. Apparently in many ways he was. At age 46, he was a doting dad to three school-aged children; the parents of their classmates have spoken of him as a regular guy, an involved member of the school community. Yes, while in his early twenties, he felt the lure of drink and drugs, but he long ago went public about his decades of sobriety. The word is that last May he briefly went off the wagon, then immediately checked himself into rehab. In the long run, alas, it didn’t work.

Why? I suspect even those closest to him are wrestling with that question. What did he need that life didn’t give him? In his chosen profession he had succeeded gloriously: though he lacked the looks of a classic leading man, there were plum roles, big paychecks, critical adulation, an Oscar. He had the respect of his peers, and a loving family. He also had, apparently, an addictive personality: he was naturally drawn to excess of all sorts. As he told a British journalist in 2011, “I had no interest in drinking in moderation. And I still don't. Just because all that time’s passed doesn't mean maybe it was just a phase. That's, you know, who I am.” Happily for me, I don’t know what it’s like to spend your life constantly fighting addiction. But others, I think, have staved off that harsh disease, even if they can never entirely conquer it.

I can’t help looking to Hoffman’s acting career as both a symptom and an underlying cause of his problems. He was best known for playing men on the edge, those who struggled with power, with sexual confusion, with greed, with obsession, with secrets they couldn’t even admit to themselves. Often his characters were abusers of some sort. Since the heyday of the Actors Studio, many American actors have been trained to probe their own emotional memories and then look for connections between themselves and their roles. I know little about Hoffman’s personal methodology, but I’d guess that bonding so intensely with the outrageous characters he played on stage and screen would ultimately take its toll.

Two of his recent powerhouse Broadway appearances stand out in my mind. Eugene O’Neill’s autobiographical Long Day’s Journey into Night lays bare a family destroyed by addiction. Willie Loman in Arthur Miller’s Death of a Salesman is not exactly an addict, but rather a man fatally determined to win success by making himself well-liked. Willie Loman’s “smile and a shoeshine” brand of salesmanship strikes me as remarkably close to an actor’s life. Hoffman smiled; sold himself for the crowd’s applause; died much too soon.

Published on February 03, 2014 15:11

January 31, 2014

Pete Seeger -- Musical Superman -- and the Super Bowl

When I think of Pete Seeger, I don’t think of movies. His impact was best felt in person: a guy with a banjo spreading the word about the dignity of work, the value of freedom, the horror of war, the desperate need to make the world a better place. Or, as one of his most famous songs would have it, to contribute to the “love between my brothers and my sisters . . . a-a-a-all over this land.”

Pete Seeger roamed the country, singing for whoever would listen, and encouraging folks to join in on the chorus. Some friends of mine once had a big adventure that speaks to Seeger’s creative activism. A New Yorker by birth, he was deploring the sorry state of the Hudson River. So in 1966 he commissioned a replica of a 19thcentury sloop, christened it the Clearwater, then gathered a group of young musicians to sail it up and down the river, singing traditional sea chanties along the way. The sloop still exists, as does Seeger’s annual music and environmental festival, the Great Hudson River Revival.

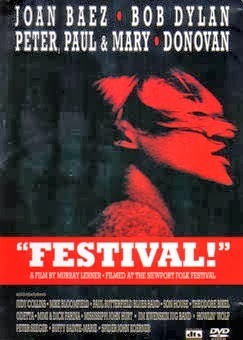

But though Seeger was best savored by live crowds, he couldn’t be everywhere at once (though he sometimes seemed so). Which is why many know him mostly through his media appearances. One such was 1967’s Festival, an Oscar-nominated documentary that chronicles performances at the famous Newport Folk Festival from 1963 through 1965. Seeger was very much in evidence, especially backstage at the notorious 1965 appearance of Bob Dylan, who chose to segue from traditional acoustic music to electric rock. The camera captures Seeger’s disapproval, though he may have been speaking more to the quality of the sound than to Dylan’s musical choices when he told audio technicians, “If I had an axe, I'd chop the microphone cable right now.” Dylan’s apparent betrayal of the folk music ethos adds drama to the documentary, which was soon followed by such major concert films as Monterey Pop (1968) and Woodstock (1970).

Also in 1967, Seeger validated his anti-war credentials on the popular Smothers Brothers Comedy Hour by singing “Waist Deep in the Big Muddy,” a song obviously referring to the dangerous escalation of the Vietnam War. His performance was snipped by the CBS brass, not the first time Seeger was treated as a serious social threat. But years later he received a Kennedy Center honor, and led Woody Guthrie’s “This Land is Your Land” at the inaugural concert of Barack Obama. I don’t recall him being mentioned in Inside Llewyn Davis, but every folk musician portrayed in that film would surely consider Pete Seeger a mentor and an inspiration.

Like Pete Seeger, the Super Bowl has owed much to mass media. It debuted in 1967, by which time most American households owned color TV sets. As we’ll surely see this Sunday, when Super Bowl XLVIII kicks off in New Jersey, the merger of sports and showbiz is part of the whole point. Among the elaborate commercials planned for this year, at least one will promote an upcoming movie, Muppets Most Wanted. (Presumably Pete Seeger was never asked to do a halftime show.)

Personally, I prefer folk music to football, and so I have not seen many movies with gridiron settings. I do remember Alan Alda playing George Plimpton, the journalist who made an unlikely neophyte quarterback in Paper Lion, but I never watched Burt Reynolds’ Semi-Tough, nor the Friday Night Lights documentary. I’ve survived, though, the corniest football movie of them all, Knute Rockne All American, with a dying Ronald Reagan heroically urging his teammates to win one for the Gipper.

Published on January 31, 2014 14:05

January 28, 2014

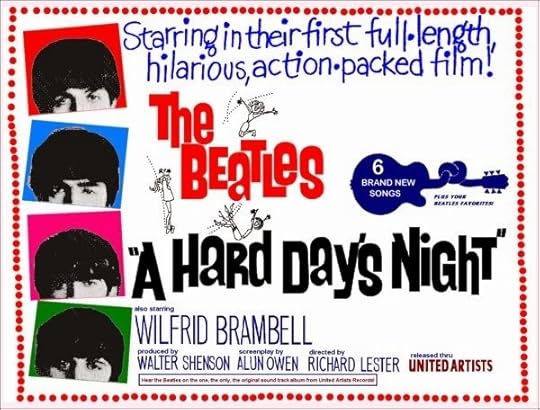

Beatlemania: A Hard Day’s Night at the Grammys

I hardly pay close attention to the Grammy Awards. My passion is film, not pop music, and such groups as Daft Punk mean nothing to me. What struck me about this year’s ceremony was the appearance onstage of several icons of my own era. Carole King, of Tapestry fame, powerfully dueted with Sara Bareilles, almost young enough to be her granddaughter. In the pop instrumental album category, the victor was none other than Herb Alpert, whose Tijuana Brass provided a peppy soundtrack for my college days. But of course the big nostalgia moment came when Paul McCartney and Ringo Starr performed together.

It was, all in all, a Beatles year. Not only did both McCartney and Starr receive lifetime achievement awards but Paul picked up a statuette for co-writing (with the surviving members of Nirvana) something called “Cut Me Some Slack,” voted 2013’s best rock song. It turns out we’re closing in on the 50th anniversary of the Beatles’ first appearance in the United States. On February 9, 1964, they rocked the Ed Sullivan Show, and my generation has not been the same since. To celebrate, CBS has just taped a two-hour tribute that will air on February 9, 2014. I wonder exactly who’ll tune in.

The Beatles became famous as musicians, of course. But at one time they also made serious waves as the stars of their own movies. Much of the credit must go to Richard Lester, a young TV director from Philadelphia. Lester attracted the attention of the madcap British actor Peter Sellers, who was looking to translate the exuberant goofiness of The Goon Show into visual form. In 1960, Lester shot The Running Jumping & Standing Still Film , a black-and-white short featuring Sellers, Spike Milligan, and other zanies romping through the English countryside, armed with eccentric props. No one spoke, but there was the occasional outlandish sound effect, as well as a bouncy jazz score.

The Beatles, particularly John Lennon, enjoyed the offhand eccentricity of Lester’s work, which is how he came to direct the low-budget film first intended by its Hollywood studio, United Artists, to be mostly a tool for promoting a soundtrack album. Instead, A Hard Day’s Night -- now considered one of the best rock ‘n’ roll films of all time -- is a cheeky look at four appealing young men trying their best to elude their own fame. Lester’s hand-held camera and frequent jump cuts capture the hyperkinetic mood of the era, and contribute to the sense of the Fab Four as literally running away from their fans and handlers to seek their own form of freedom. Their on-screen personas (John as a smart-ass; Paul as sweet and sensible; George as shy; Ringo as endearingly awkward) seem real, and remain lodged in our brains, as does Lester’s much-imitated quirky style (see below).

Lester’s second Beatle film, Help!, is in color, and has an actual plot. It’s a spoofy comic adventure story with certain James Bond echoes, plus Ringo (of course) as the Beatle who almost gets sacrified by an evil eastern cult. Of the foursome, only Ringo went on to pursue an actual acting career, almost always playing eccentric roles (like the Mexican gardener in Candy). He has also done his share of whimsical children’s television shows, such as Shining Time Station.

As for Richard Lester, he ultimately went mainstream in a big way, directing everything from The Three Musketeers to Robin and Marian to 1980’s Superman II. Oscars have eluded him, but last year the Los Angeles Film Critics honored his career achievement. What took them so long?

Speeaking of musicians, a fond farewell to the ageless Pete Seeger, whose eventful life has just ended. I never met him, but he felt like a favorite musical uncle. His music will never die, so long as there’s a campfire to sing around.

Published on January 28, 2014 09:24

January 24, 2014

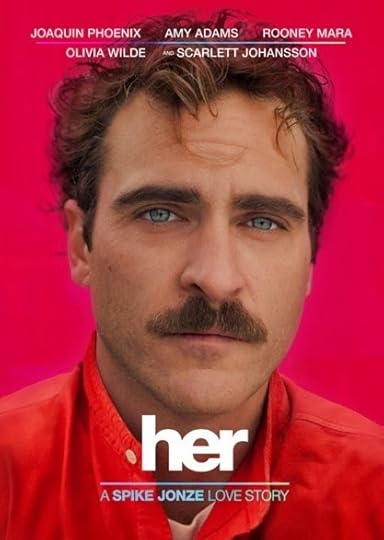

A Hymn for “Her”

A highly entertaining post from Buzzfeed.com presents forty movies that define L.A. Included on the list drawn up by Buzzfeed staffer Louis Peitzman are selections that are tawdry (Beyond the Valley of the Dolls), scary (Pulp Fiction), goofy (Fast Times at Ridgemont High), and baffling (Mulholland Drive). Though L.A. films tend – for some reason -- to focus on the grotesque side of life, there are even some entries that are downright romantic, with (500) Days of Summer earning top honors in that department. Of course I noticed some serious omissions. Where, for instance, is The Graduate? In any case, a new release that just won a Golden Globe for best original screenplay deserves some attention as a romantic, though quixotic, L.A. film. I’m talking about Spike Jonze’s latest, Her. Her, as everyone knows by now, chronicles the love between a young man and his computer operating system. I knew in advance that Joaquin Phoenix, surprisingly convincing as a gentle and sensitive soul, would fall hard for the OS of his smartphone, bewitchingly voiced by Scarlett Johansson. What I didn’t expect going in was a fascinating view of L.A. as the city of the future. The world of Phoenix’s Theodore Twombly is hardly the dystopia we see in L.A. science-fiction flicks like Blade Runner. Instead, it’s quite lovely, and in many ways familiar to a longtime SoCal resident like me. Downtown L.A., where most of the story is set, includes such familiar landmarks as Disney Hall, the Biltmore Hotel, and various iconic high-rises. But these features of the current cityscape are dwarfed by much sleeker, much taller buildings, like the one in which Theodore lives. (The filmmakers went to Shanghai to shoot a number of that city’s fanciful skyscrapers, then used CGI to incorporate them into today’s L.A. skyline.)

Another remarkable aspect of the L.A. of the future: apparently no one drives. Entering one of the city’s most colorful metro stations, Theodore hops a train to take his love (safe in his pocket) to the beach. The “subway to the sea” has long been a dream of certain L.A. politicians, so I’m glad this film proves that it will one day become a reality.

But my favorite futuristic detail about Theodore’s life involves his job. As a valued employee at beautifulhandwrittenletters.com, he sits in a cubicle, crafting emotional messages for clients who are too tongue-tied to express their own thoughts. (Shades of Cyrano de Bergerac, now that I think of it!) The futuristic twist is that Theodore need only speak his artful words aloud: his computer screen automatically translates them into the handwriting of the ostensible sender. Perhaps in the future that’s as close as we’ll come to a from-the-heart personal letter. Which means that the handwritten thank-you note I received the other day from fellow author Pat Broeske is something I should definitely treasure.

Much of the publicity surrounding Her has detailed how Johansson’s entirely vocal role was originally played by the British actress, Samantha Morton. Morton was tasked with speaking her lines on set, hidden in a black plywood box, to create a sense of genuine interaction with Phoenix’s Theodore. It was only later that Jonze decided to substitute Johansson’s expressive voice for Morton’s. Somehow it seems most appropriate: in a story where human beings are so disconnected from one another that a man can fall deeply in love with a computer function, the actress around whose voice Phoenix built his performance gets replaced by someone entirely different. But entirely wonderful. No surprise that Theodore’s beloved OS is such a hit on double dates.

Published on January 24, 2014 12:00

January 21, 2014

Goodbye, Jose Jimenez?

The recent passing of veteran actress Carmen Zapata, best known to the moviegoing public for playing a nun in Sister Act, made me think about the status of Latin Americans in Hollywood. Carmen, born in New York to a Mexican father and Argentine mother, had a longstanding gig as Doña Luz on PBS’s bilingual children’s program, Villa Alegre. Bilingual programming was very close to her heart. When I interviewed her in 1973, she had just helped found a Los Angeles theatre group, the Bilingual Foundation of the Arts. It still exists, providing training for actors, translating Spanish-language drama into English, and presenting plays in both languages.

My interest in Hollywood’s Mexican-American heritage was first piqued when I visited the LA Plaza de Cultura y Artes, a stone’s throw from Downtown L.A.’s kitschy Olvera Street. The Plaza’s splendid new museum colorfully illustrates the history of Mexican Americans in Southern California. The section on the movie industry points out that, in the era of silent films, Mexican-born actors had no problem finding acceptance in Hollywood. Ramon Novarro played Ben-Hur and other mainstream leading-man roles; Dolores del Rio, Lupe Velez, and the handsome Gilbert Roland became stars. When talkies arrived, though, Mexicans were suddenly limited to stereotypical parts: the Latin Lover, the charro, the seductress, the spitfire.

Years later, the great Anthony Quinn (born in Mexico, raised in East L.A.) enjoyed a major career, but one that tended to confine him to ethnic and outrageous roles. In the banner year 1956 he played Quasimodo in The Hunchback of Notre Dame and won an Oscar for portraying Paul Gauguin in Lust for Life. He was an Arab in Lawrence of Arabia (1962), danced joyfully on a Cretan beach in Zorba the Greek (1964), and often played Italian, as in The Secret of Santa Vittoria (1969).

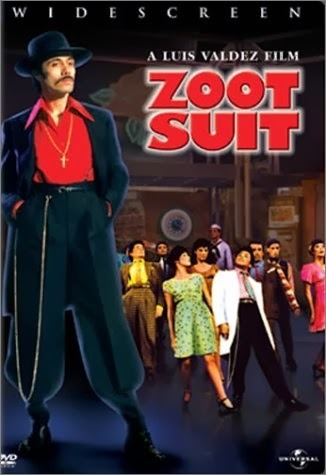

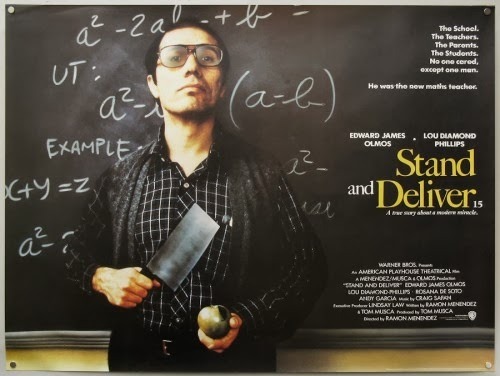

It was in 1965 that Luis Valdez founded a farmworkers’ theatre, El Teatro Campesino, in rural Delano, California, as the cultural arm of the United Farm Workers. Early performances were strongly political, with a focus on Chicano issues. By 1978, the troupe had grown sophisticated enough to interest L.A.’s respected Center Theatre Group. Zoot Suit highlighted the racial injustice surrounding the infamous Sleepy Lagoon Murder trial of 1942. The production galvanized Los Angeles, and made a star out of Edward James Olmos, who played the iconic El Pachuco. When I met Olmos behind the scenes, he was friendly and soft-spoken, but he commanded the stage in a way that was unforgettable. His 1981 role in a film version of Zoot Suit led to a key non-ethnic part in Blade Runner, and then a Best Actor Oscar nomination for portraying gutsy teacher Jaime Escalante in 1988’s Stand and Deliver. (Valdez himself, six years after directing the Zoot Suitfilm, had his biggest Hollywood moment at the helm of La Bamba, the Richie Valens story.)

Today, of course, there’s more opportunity for Latino actors like Salma Hayek, Oscar-winner Benicio del Toro, America Ferrera, and Andy Garcia (who got some of his training at Carmen Zapata’s Bilingual Foundation of the Arts). But old stereotypes die hard, and plenty of Latin-Americans are still stuck playing gardeners and maids. A young Broadway actress with Mexican roots recently appeared in a new musical production, in the role of a beauty queen. The part required her to be ditzy, but ethnically neutral. Then the producers asked for a change: could she lay on a thick Chica accent? She could and did (a featured role is featured role!), and the shift generated a lot of laughs. Still, though, it didn’t feel good.

Published on January 21, 2014 12:00

January 17, 2014

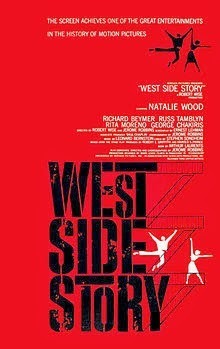

Rita Moreno: SAG Honoree, Survivor, Sucker?

When I was in high school, Rita Moreno was an icon to all of us. In the hugely popular film version of West Side Story, she played the character that we girls most admired. Few of us would want to emulate Natalie Wood’s Maria, who was a little too nice and a little too sad for our tastes. Moreno’s Anita, though – that was a woman! She danced up a storm in those terrific ruffled dresses, sang passionately about her mixed feelings for “America” (we had mixed feelings too), and had the best-looking on-screen boyfriend, bar none. Moreover, you had to love her spunk. No wonder she won the Oscar for best supporting actress of 1961. And no wonder SAG is giving her its 2014 lifetime achievement award.

Born in Puerto Rico, Moreno was the rare member of the West Side Story cast who actually matched the ethnicity of her role. (By contrast, George Chakiris is Greek American, and the late Natalie Wood had Russian roots.) The perfect embodiment of the Latin-American spitfire, Moreno often found herself in roles that reinforced the familiar stereotypes. (For instance, she played Señorita Delores in a 1958 episode of the Red Skelton Show titled “Clem the Bullfighter.”) Which is why I was later surprised to realize she’d also played very different parts, including significant roles in two of Hollywood’s best musicals. In Singin’ in the Rain, she was Zelda Zanders, a cute but thankfully non-ethnic starlet. Four years later, she played Indochinese as the tragic Tuptim in The King and I.

After her Oscar win (followed by an Emmy, a Grammy, and a Tony award), Moreno never got offered another film role that was worthy of her talents. I remember her making a brief appearance in Carnal Knowledge, and playing the lurid part of a drug-addled stewardess in one of my least favorite movies of all time, The Night of the Following Day. In this turgid 1968 film, a young heiress flying to France is kidnapped by a chauffeur -- the bizarrely blond-haired Marlon Brando -- and taken to a beach house where some ill-assorted thugs do unspeakable things to her and to one another. I will not reveal the twist ending (though I’m not sure why I should be so kind to a film so annoying). Suffice it to say, I was sad to see Moreno in a role thoroughly lacking in dignity.

Her appearance in that film made slightly more sense when I glanced at her eponymous 2013 memoir, which devotes many pages to her tempestuous eight-year affair with Brando. When she met him, at age 22, she fell hard: “To say that he was a great lover -- sensual, generous, delightfully inventive -- would be gravely understating what he did, not only to my body, but for my soul. Every aspect of being with Marlon was thrilling, because he was more engaged in the world than anyone else I’d ever known.” So deeply was she in thrall to Brando that she endured countless infidelities, plus an illegal abortion. She tried dating others (including Elvis!) in a vain attempt to make him jealous. Ultimately, when he abandoned her to marry his Tahitian co-star from Mutiny on the Bounty, she tried suicide.The Night of the Following Day came much later, briefly rekindling a relationship that seemed doomed from the start.

Given that she continues to perform with élan on stage and screen, I guess you can say she’s the ultimate survivor. Sorry, Rita. I’d much rather salute you for your achievements than read about you degrading yourself for someone who never recognized your worth.

Published on January 17, 2014 12:00

Beverly in Movieland

I write twice weekly, covering topics relating to movies, moviemaking, and growing up Hollywood-adjacent. I believe that movies can change lives, and I'm always happy to hear from readers who'd like t

I write twice weekly, covering topics relating to movies, moviemaking, and growing up Hollywood-adjacent. I believe that movies can change lives, and I'm always happy to hear from readers who'd like to discuss that point.

...more

- Beverly Gray's profile

- 10 followers