Beverly Gray's Blog: Beverly in Movieland, page 125

December 10, 2013

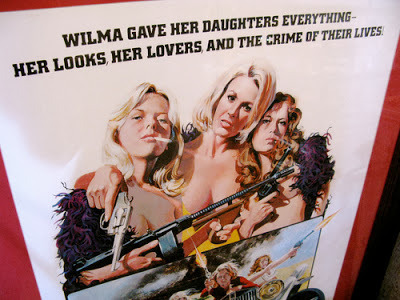

Big Bad Mama Rides Again

Not long ago, 82-year-old Angie Dickinson was interviewed by film historian Stephen Farber. When asked about her starring role in a 1974 Roger Corman gangster romp, she said something like this: “Big Bad Mama does not qualify as a classic, although I was very good in it!"

She was indeed. As a dirt-poor Depression-era Texas mom who turns to a life of crime to give her daughters a better future, Angie is spunky, smart, and above all sexy. In the course of the film she beds both a virile young stud (Tom Skerritt) and a courtly older gentleman (William Shatner), but there’s never any question that she’s the one on top. Whether delivering bootleg whiskey, robbing a bank, or plotting to hold an heiress for ransom, she’s the brains behind the operation, while also tenderly mothering her two nubile daughters. No question that the role kept her busy, but cast and crew all adored her. I should know: I was there.

Vince Rotolo and the good folks behind The B-Movie Cast recently invited me to share my memories of this New World Pictures classic. When I came to work for Roger, my colleague Frances Doel was hard at work on a female gangster story, a more light-hearted variant on Bonnie and Clyde and Roger’s own Bloody Mama. It was Roger’s practice, as a Writers Guild signatory, to get someone around the office to crank out a first draft over a weekend, so he’d only have to pay a guild member a rewrite fee. We next found a Hollywood veteran, Bill Norton (White Lightning), who didn’t realize that the script he was hired to improve had been written by the woman sitting across the desk in our story meetings. He only learned the truth when we got the giggles over his request to meet the originator of the story. At which point he very graciously insisted that Frances share his writing credit. (A modest woman, she still claims he was trying to evade taking full responsibility for the screenplay’s faults.)

Truth be told, the script is a lot of fun. It was a challenge to film, though, as director Steve Carver would be the first to tell you. We had to track down inexpensive 1930s-era locations, like a racetrack, a country church, a small-town Main Street, and a society mansion, all not far from L.A. Vintage cars and weapons too. Somehow we found what we needed, and persuaded such Hollywood pros as Royal Dano, Noble Willingham, and a very naked Sally Kirkland to help fill out our cast.

Yes, this was a movie that did not stint on T&A. Tom Skerritt was fine with it, but William Shatner proved a shrinking violet. (It didn’t help that Skerritt, whose character was supposed to be hostile to Shatner’s, took every opportunity to knock his toupee askew.) As for Angie, she knew that Roger expected full frontal nudity. A very sleek 43-year-old, she was comfortable in her skin, and had no hesitation in baring it for the camera. Her example was helpful to the plucky young women playing her daughters, Robbie Lee and Susan Sennett (now the wife of Graham Nash). The script calls for them to frequently take it all off, especially in a steamy ménage à trois scene with lucky Skerritt.

As production secretary I once fielded a call from Playboy, asking if the two were centerfold material. When I explained that Angie had the best figure in the film, the female caller sniffed, “Well, I hope I look as good when I’m her age.” You wish, lady. You wish.

Published on December 10, 2013 09:42

December 6, 2013

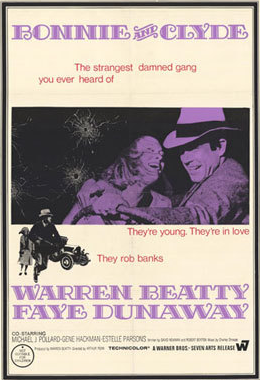

The Return of Bonnie and Clyde

So cable TV is taking a crack at Clyde Barrow and Bonnie Parker. Three networks -- History, Lifetime, and A&E -- have joined for a simulcast of the mini-series Bonnie & Clyde, scheduled to begin on December 8. In dramatizing a violent episode from America’s past, they’re hoping for the sort of ratings bonanza enjoyed by last year’s Hatfields & McCoys. The reviews I’ve seen don’t make the simulcast (starring Emile Hirsch and Holliday Grainger as the doomed outlaws) sound promising. I’m guessing it will have no more impact than a Broadway musical about the pair, which eked out a mere 36 performances in 2011.

One problem, of course, is that it’s tough to measure up to Arthur Penn’s brilliant 1967 film, which unerringly walked the fine line between comedy and tragedy. Penn’s two leading actors, Faye Dunaway and Warren Beatty, were perfectly cast. Beatty was also the film’s dauntless producer, sweet-talking Jack Warner into financing his passion project and then, when Warner hated the finished film, rescuing it from oblivion and delivering it into the hands of influential critics like Pauline Kael.

Bonnie and Clyde became a hit partly because it meshed so well with the concerns of its day. The story of two Depression-era outlaws might have meant nothing special to audiences in some other decade. But in 1967, in the wake of the JFK assassination and the escalating war in Vietnam, violence had become a national obsession. And hip young audiences were also increasingly sensitive to questions of social inequality. When I spoke to Arthur Penn in 2008, he made clear the extent to which he had added to Robert Benton and David Newman’s sexy New Wave-inspired script a social consciousness that grounded the lovers’ story in the realities of the 1930s, while also touching on issues that mattered hugely to the emerging Baby Boom generation.

Vietnam was very much on Penn’s mind. In World War II he had seen combat as an infantryman at the Battle of the Bulge. The experience quickly convinced him of the insanity of war: “It was not glorious, not organized, nothing. Nobody knew what the hell they were doing; it was just save your life and chaos.” That’s why, when he came to make Bonnie and Clyde, “I had decided not to mollycoddle the audience about shooting and death. This, after all, was wartime.”

Penn was also remembering the Kennedy assassination, which suggests itself subliminally in the way Clyde’s head is blown apart during the final ambush. Penn emphasized what he considered a fundamentally American bloodlust in the “Ring of Fire” sequence where the outlaws, including a badly wounded Buck Barrow, are surrounded by a circle of men with shotguns. The whooping and the hollering and the rebel yells as the posse moves in on its prey reveal that these representatives of law and order enjoy bloodletting as much as the criminals do.

Penn also showcases the plight of society’s disenfranchised from a Sixties perspective. He doesn’t just focus on Okies, but also positions in the background of many scenes the sort of humble rural black man who three decades later would be the focus of the civil rights movement. At climactic points in the story you can spot down-home African-Americans lounging on a bench or driving past in a truck, essentially functioning as a silent Greek chorus. Once Clyde briefly clasps a black man’s hand in friendship, a taboo gesture in 1930s Texas. Just one more reason why young viewers in the Sixties connected so viscerally with a drama about a pair who’d lived, loved, and died thirty years before.

It’s a strange segue from killers to a man of peace, but I want to at least mention the passing of the remarkable Nelson Mandela. Ironic indeed that a new biopic, Mandela: Long Walk to Freedom, is just now coming into theatres. I gather that its focus is Mandela the saint, rather than the more complicated flesh-and-blood human being, but it seems worth attention nonetheless.

Published on December 06, 2013 09:45

December 3, 2013

David Groves and the Magic of Storytelling

David Groves tells stories. I know him as a career journalist, a fellow member of the American Society of Journalists and Authors. But he’s also dabbled in fiction from an early age. That’s partly why he – still in his teens – connected with the young Gale Anne Hurd, who also aspired to write. Over the years they lost touch, alas, so you won’t see his writing credit on Hurd’s The Walking Dead anytime soon.

David Groves tells stories. I know him as a career journalist, a fellow member of the American Society of Journalists and Authors. But he’s also dabbled in fiction from an early age. That’s partly why he – still in his teens – connected with the young Gale Anne Hurd, who also aspired to write. Over the years they lost touch, alas, so you won’t see his writing credit on Hurd’s The Walking Dead anytime soon. But now David’s the proud author of a powerful suspense novel, What Happens to Us . Which doesn’t mean he doesn’t have movies on the brain. Though he’s writing for the page and not the screen, he considers his new work cinematic in structure: “The protagonist is always in peril, and the viewer knows it. This keeps the viewer on the edge of the seat even when things are slow.” There’s a seemingly unstoppable bad guy, one who uses modern surveillance technology to track his victims, and the plot builds to a breathless conclusion that takes his protagonist up to the point of death – and practically beyond it.

That protagonist is a smart, tough, but deeply conflicted young woman. (In a movie version, David would consider Jennifer Lawrence dream casting. Or maybe Emma Stone.) Though she’s clean and sober when the story begins, her years of alcoholism have put a monster on her trail. Only by returning to the drinking habits of her flamboyant alter ego, Kick, can she begin to figure out why he’s so determined to chase her down. In creating this character, David did not stint on research, but he’s most indebted to Koren Zailckas’s Smashed: Story of a Drunken Girlhood, because “what I needed was the raw, embarrassing stories from a female alcoholic’s life to teach me what the pattern was. That book spared nothing.”

At the movies, of course, there are alcoholics aplenty. David mentions particularly Clean and Sober (“The lies, the bargains, the price he had to pay. He really hit bottom.”) Other films he admires include Crazy Heart, Tender Mercies, and the recent Flight, which taught him that “you have to be able to hurt or kill some of your characters if you’re going to have an impact on the viewer or reader.” He dislikes the portrayal of alcoholics in Arthur, and in such classics as Harvey, The Philadelphia Story, and even It’s a Wonderful Life, for showcasing what Hollywood has tended to consider “the funny and harmless drunk. None of them are harmless.”

When he’s not writing, David is a working magician, a member of Hollywood’s famous Magic Castle. To him, sleight of hand is not so different from what a novelist or filmmaker does: “Magic is an elaborately designed deception. So is a novel or a film. There is no Luke Skywalker, but Lucas convinces us he exists, if just for that hypnotic moment inside the theatre.” The secret, for both wordsmiths and magicians, lies in the power of misdirection. See below for a sample of David’s magical talents at work.

As for designing a magic act, “it’s very similar to designing a novel or a movie. What you’re manipulating is the interest of the audience, and the same principles apply.” These being:

Start with a quick bang.

Invite the audience into your head and soul.

Make them identify with you.

Hit different notes all the time, never repeat.

Create callbacks.

Create consistent themes.

Whenever possible, include secrets and withheld information.

Whenever possible, include lies.

End with your best stuff.

Convince them the protagonist is about to fail, then let him or her succeed beyond their wildest dreams.

Published on December 03, 2013 11:50

November 28, 2013

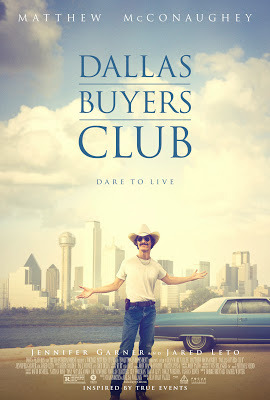

The Straight Skinny on “Dallas Buyers Club”

There’s much to admire about Matthew McConaughey in Dallas Buyers Club. In the role of Ron Woodroof, a cocky Texan whose HIV-positive status leads him to battle the FDA and the medical establishment, McConaughey is both powerful and nuanced. And at times extremely funny too. But virtually every review praising his performance mentions that he lost over thirty pounds (or forty, or fifty, despending on what source you read) to achieve the skeletal frame of a man dying of AIDS. This was a far cry from his 2012 Magic Mike, in which he buffed up to play a male stripper.

McConaughey isn’t the first Hollywood star to punish his body in the service of his art. Tom Hanks also got skinny to play an AIDS sufferer in Philadelphia. For Cast Away he ate himself pudgy to portray a sedentary middle-aged guy. Then production was halted for a year of serious dieting so that he could look suitably gaunt as a man marooned on a South Pacific island. Hanks recently revealed he’s got Type 2 diabetes, a situation that may (or may not) have been encouraged by his years of yoyo-ing weight.

Other stars who’ve lost major poundage to take on dramatic roles include Christian Bale (The Fighter), Matt Damon (Courage Under Fire), Matthew Fox (Alex Cross), and Curtis “Fifty Cent” Jackson, who played a football star battling cancer in All Things Fall Apart. Michael Fassbender starved 42 pounds off his frame when portraying real-life Irish hunger striker Bobby Sands in Hunger. Another actor who whittled himself to a point of near starvation was Adrien Brody, playing a Warsaw musician hiding from the Nazis in The Pianist.

Brody won a Best Actor Oscar for his pains, the youngest man ever to do so. Likewise Tom Hanks was honored for Philadelphia, and McConaughey is considered a serious Oscar contender this year. In 2011, Christian Bale won for his supporting role in The Fighter, and Jared Leto (who also dropped significant weight to play – brilliantly -- a transsexual AIDS patient in Dallas Buyers Club) is frequently mentioned in this category. So acquiring a lean and hungry look can have its rewards. Obviously, Oscar voters are impressed by guys who go without dinner.

Women who’ve found success in today’s Hollywood of course know a thing or two about dieting. Even for those who are NOT playing cancer patients or concentration camp inmates, thin is definitely in. The web is full of blow-by-blow accounts of the workout and dietary regime that allowed the already slender Anne Hathaway to squeeze into her cat suit for The Dark Knight Rises. She went beyond slim and slinky to play the tortured Fantine in Les Miserables. For this she too won an Oscar, along with (I suspect) the adulation of teenage girls keen to latch onto her diet secrets.

The determination by Hollywood stars to lose weight at all costs is nothing new. Back in 1967, Faye Dunaway was cast as outlaw Bonnie Parker in Arthur Penn’s Bonnie and Clyde. Her previous film had been Otto Preminger’s Hurry Sundown, a Southern-fried melodrama in which she played the supporting role of a hearty country gal. Costume designer Theadora Van Runkle confirmed to me Dunaway’s instinctive sense that she’d need to be thinner to do justice to Bonnie’s 1930s look. She slimmed down almost overnight, strictly through will power: “I never saw her eat anything.” Which made Dunaway not the pleasantest person to have on a movie set. But what price glory?

All the above is making me mighty hungry, so I think I’ll go gobble some pumpkin pie. Happy Thanksgiving!

Published on November 28, 2013 09:43

November 26, 2013

A Time to be Thankful: Syd Field and Mickey Knox

As Thanksgiving approaches, I’m both thankful and sad. I’m thankful for the Hollywood personalities I’ve had the good fortune to meet, and sad that many are no longer with us. In November alone, we lost two who made a difference.

I was introduced to Syd Field at a behind-the-scenes staff event that heralded the opening of the Getty Center in Brentwood. Our meeting took me by surprise: somehow I’d never thought of him as a man, but rather as a series of screenwriting books (beginning with 1979’s Screenplay) that today’s Hollywood regards as gospel. When it comes to the arts, I’m resistant to any hard and fast rules, except for the one voiced by screenwriter William Goldman, who famously said, “Nobody knows anything. . . . Not one person in the entire motion picture field knows for a certainty what’s going to work. Every time out it’s a guess and, if you’re lucky, an educated one.”

But surely Syd Field should get credit for educated guesses. His focus on the three-act structure has influenced everyone from Judd Apatow to Alfonso Cuarón. It has also influenced young development executives who talk in Field speak and will not tolerate any deviation from the Field model when it comes to the placement of plot points. Field himself, remarkably, turned out to be low-key and modest about his place in the screenwriting firmament. One thing I’m sure of: he truly loved movies.

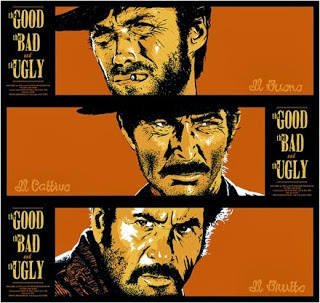

So did Mickey Knox. I first met Mickey in 2005 through my friend Bella Stander. He’d been a chum of her late father, the gravel-voiced character actor Lionel Stander, during the bad old Blacklist days when both were hanging out in Rome. During Bella’s L.A. visits, Mickey would end up eating at my dinner table. He gave me a copy of his 2004 memoir, The Good, the Bad, and La Dolce Vita, a rollicking and sometimes bawdy tale of a life much enjoyed.

I never knowingly saw Mickey on film. What I learned from his book was his importance behind the scenes, especially when working with legendary Europeans as a translator and dialogue coach. He supplied the English-language dialogue for Sergio Leone’s The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly, then worked with Leone to cast and shoot Once Upon a Time in the West. He also taught Anna Magnani to handle her English-language lines in The Rose Tattoo, which ultimately won her an Oscar. Beyond this, Mickey – like Zelig – was always where the action was. When Marlon Brando dropped trou in front of Magnani, Mickey was there. On the set of White Heat, James Cagney addressed him in fluent Yiddish. Robert Capa gave him photography tips, and Willy Shoemaker told him what horse to back. He pigged out with Orson Welles, beat John Wayne at chess and Omar Sharif at gin rummy. Shelley Winters and Zsa Zsa made passes; so did Tennessee Williams. Ava Gardner didn’t, but he got to massage her sore feet.

Did Mickey merely have a vivid imagination? His stories, wild as they are, have the ring of truth. And J. Michael Lennon’s new scholarly biography of Norman Mailer confirms that the two were the best of friends. In 1970, Mickey had already left the party when Mailer viciously stabbed his wife Adele. The next day, however, it fell to Mickey to retrieve the knife with which his pal had done the deed.

In his book, Mickey never makes excuses for his own lapses. His brash but good-natured personality comes through loud and clear. When he came to dinner, I wish I’d asked more questions.

Published on November 26, 2013 09:34

November 22, 2013

November 22, 1963: Lee Harvey Oswald at the Movies

For those of a certain age, the mere mention of November 22, 1963 sends chills down the spine. The assassination of President John F. Kennedy in Dallas, fifty years ago today, has forever changed Baby Boomers’ view of the world. We believe in conspiracies. We resist putting our faith in big institutions. We don’t quite trust anybody, either over or under thirty.

As the fiftieth anniversary drew near, several articles were written about how the Kennedy assassination gave rise to paranoid movie thrillers. A good piece in a Hollywood-based site called TheWrap mentions Blow-Up, The Parallax View and The Conversation as just three of the films shaped by what happened that day in Dallas. On television, in recent years, we’ve had 24 and Homeland. The very fact that Americans continue to puzzle over the Zapruder footage of the assassination (and that the footage were edited into Oliver Stone’s controversial JFK) shows the extent to which motion pictures are intertwined with one of the darkest days in American history.

What’s not generally remembered is that Lee Harvey Oswald, the shadowy former Marine who was long ago named Kennedy’s assassin in official reports, was captured by police at a suburban Dallas movie house called the Texas Theatre. He’d slipped inside without paying, and was watching a double bill of Cry of Battle and War Is Hell when an alert assistant manager notified law enforcement. The lights came on and, following a brief scuffle, Oswald was arrested. (After many financial ups and downs, the theatre survives today as an historic and cultural landmark.)

At the Margaret Herrick Library of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences, while researching film in the Sixties, I happened upon an odd little book by someone named John Loken. Loken seems to like arcane research: his only other publication is an analysis of the possibility that the Shroud of Turin is the authentic burial shroud of Jesus. But in 2000 he released a pamphlet-sized work called Oswald’s Trigger Films. It delves into the possibility that Lee Harvey Oswald, whom Loken accepts as JFK’s lone assassin, was goaded into lethal action by the movies he favored.

Oswald frequently went to the movies alone. (His Russian-born wife didn’t understand American movies.) The Palace Theatre was a prominent movie palace seven blocks from his workplace, and clearly visible along his bus route. From November 14 through December 12, 1962, it featured a chilling drama called The Manchurian Candidate; this film (in which a young man is brainwashed into gunning down a presidential candidate) also later played at the Texas Theatre, located close to Oswald’s apartment. Loken, unlike some conspiracy theorists, doesn’t think of Oswald as a dupe programmed by outside forces into killing Kennedy. Instead he speculates that Oswald – who loved intrigue and saw himself as a James Bond-type man of action – was moved to imitate the film’s central image of an assassin on high, targeting his prey through a rifle’s telescopic sights.

It can’t be verified that Oswald saw The Manchurian Candidate. But in October 1963, according to his widow Marina, he twice watched on television a 1949 John Garfield flick, We Were Strangers, in which a Cuban patriot engineers the death of a dictator. And, just maybe, he also saw 1954’s Suddenly, in which gangsters led by Frank Sinatra plot a presidential assassination. (It was withdrawn from circulation after JFK’s death.) According to Loken, it makes perfect sense that Oswald -- once he’d changed the course of American history -- sought refuge in “the dream world of a movie theater showing violent films.”

Published on November 22, 2013 11:02

November 19, 2013

The Governor Awards – From Corman Confab to Campaign Stop

Depending on which report you read, the star of Saturday evening’s Governors Awards banquet was either a glowing Angelina Jolie, a classy Steve Martin, or an ageless charmer, Angela Lansbury. They (along with costume designer Piero Tosi) were all being honored by the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences for lifetime achievement, with Jolie receiving the Jean Hersholt Humanitarian Award for helping refugees around the globe. The banquet is meant as a way for Hollywood to celebrate its own in relaxed fashion, away from the insanity of the Oscar broadcast. This year, however, the gathering morphed into something quite different: a chance for aspiring Oscar nominees to strut their stuff. Though the ceremony was not televised, it was preceded by a full-fledged red carpet for arrivals, and such awards hopefuls as Bruce Dern (Nebraska), Margo Martindale (August: Osage County), and Barkhad Abdi (Captain Phillips) made themselves highly available to the roving press corps. No question -- what was first conceived as a low-key party is now an early campaign stop.

Things were rather different in 2009 when director Norman Jewison kicked off the first Governors Awards festivities by exulting, “We’re gathered here together, all artists, celebrating excellence, without any television cameras. Isn’t it great!” That inaugural year, honorees included actress Lauren Bacall, cinematographer Gordon Willis, producer John Calley, and my former boss, Roger Corman. During the cocktail hour, I’m told former Cormanites stormed the hors d’oeuvres table, true to the tradition that Corman folk are always hungry, because they don’t earn enough to feed themselves properly.

Over dinner, the tributes to Roger came first, and (because no time restrictions were imposed) they dominated much of the evening. Everyone who sang his praises was an Oscar winner. First up was Ron Howard, who described himself as “a proud graduate of what I like to define as RCUPC—Roger Corman University of Profitable Cinema.” Next to speak was Quentin Tarantino, who confessed that he’d spent his growing-up years as the ultimate Corman fan. Tarantino screened clips from a range of Corman movies, including a memorable scene from X: The Man With the X-Ray Eyes in which the mild-mannered scientist played by Ray Milland discovers he can now see through women’s clothing. After a spirited run-down of the Corman legacy, Tarantino brought his speech to a dramatic crescendo: “Roger, for everything that you have done for cinema, the Academy thanks you, Hollywood thanks you, independent filmmaking thanks you, but most importantly—for all the wild, weird, cool, crazy moments you’ve put on the drive-in screens—the movie-lovers of the planet Earth thank you!” Jonathan Demme then stepped forward to praise “the power, the depth, the humanity, the social commentary, and the unbound imagination of Roger’s extraordinary body of work as an artist.” Calling the moment “the thrill of a lifetime,” he summoned Roger to the stage to accept his Oscar. Roger’s brief, elegant speech touched on film as a blend of art and commerce, then ended with a challenge: “I believe the finest films being done today are done by the original innovative filmmakers who have the courage to take a chance and to gamble. So I say to you . . . keep gambling, keep taking chances.”

The words were stirring, though some onlookers might have quietly remembered that Corman’s own years of true artistic risk-taking were far behind him. Meanwhile, attention finally turned to the evening’s other nominees. But even Warren Beatty, preparing to salute John Calley (The Remains of the Day), paused to quip, “I hadn’t realized that I really never worked with anyone who didn’t start with Roger.”

As a former Cormanite myself, I feel entitled to add a brief commercial message: you’ll find lots more about the Governors Awards banquet in the pages of my Roger Corman: Blood-Sucking Vampires,Flesh-Eating Cockroaches, and Driller Killers (new 3rd edition, available now).

Published on November 19, 2013 08:34

November 15, 2013

“Fallout”— Kat Kramer Out to Change the World

On Wednesday night, much of L.A.’s “cool” contingent was at Hollywood’s Chinese Theater, watching a celebrity-studded premiere of The Secret Life of Walter Mitty, a highlight of the American Film Institute’s annual fest. That same evening, not far away, a handful of showbiz greats turned up to contemplate a far graver topic: nuclear proliferation. The occasion? The fifth anniversary of Kat Kramer’s Films that Change the World. Kramer was introducing to America the film Fallout. This Australia documentary charts the history of nuclear warfare, while also chronicling how Nevil Shute’s novel, On the Beach, evolved into Stanley Kramer’s hard-hitting 1959 movie.

Of Stanley Kramer’s four children, Kat (named for her godmother, Katharine Hepburn) is the one who’s come closest to following in her father’s footsteps. She told me that Stanley Kramer’s brand of socially conscious filmmaking “is in my DNA.” He was famous for producing and directing films (like The Defiant Ones, Judgment at Nuremberg, and Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner) that tackled the day’s leading issues through dramatic storytelling. But the films in her series tend to be documentaries, like Teach Your Children Well (which takes on homophobia and schoolyard bullying) and The Cove (it won an Oscar for exposing the secret slaughter of dolphins near a Japanese village). Kat emphasized to me that today it’s documentaries that “have their own voice.” Unlike Hollywood features, so often made by committee and beholden to major commercial interests, a documentary can be fearless about making a strong statement.

The evening began with the inevitable lineup of stars for the paparazzi to photograph. There were Lily Tomlin and Louis Gossett Jr. (both of whom would later address the group), as well as such where-are-they-nows? as Jerry Mathers, who used to be known as TV’s Beaver Cleaver. I was tickled to see the still-handsome George Chakiris, all black hair, black stubble, and jet-black clothing. In fact, black seemed to be the color of the evening, in Kat’s case accented with silver lamé and with the oversized earrings that are a personal trademark. It felt like your usual celebrity red carpet, until the program began, with Tomlin introducing her close friend, Dr. Helen Caldicott.

Caldicott, an Australian pediatrician and author, was inspired by On the Beach to become an activist against nuclear energy. She’s a true pit bull on the subject, though a pit bull who’s bubbling over with humor and charm. Her charm doesn’t blunt her basic message: “We get really close to nuclear war quite often.” Such a war could come at any moment, and if it does, she predicts an impending ice age, in which “we’ll all freeze to death in the dark.” Before that happens, however, there’s also the danger posed by climate change, as witness recent disasters in the Philippines and Japan, where the tsunami-damaged Fukushima nuclear reactor is now leaking radiation into our atmosphere and our oceans.

With the present looking so grim, it was a pleasure to go back to the past through Lawrence Johnston’s documentary, Fallout. We learned that Nevil Shute, an English engineer who discovered a talent for writing, was normally relaxed about peddling his adventure novels to film companies. On the Beach, though, was a different story. In depicting Melbourne, Australia as humanity’s last stand in the face of encroaching radiation from a nuclear blast, Shute identified strongly with the nuclear engineer (Fred Astaire in the film) who blames himself and his colleagues for the destruction of mankind. Stanley Kramer’s movie is still haunting, but Shute never accepted the dramatic tweaks that an American filmmaker brought to his own singular vision of Armageddon.

PS A warm farewell to the fascinating Mickey Knox, actor, blacklist survivor, and buddy of Norman Mailer, who passed away this morning. More on Mickey later.

Published on November 15, 2013 12:38

November 12, 2013

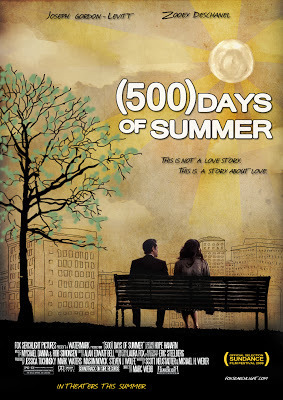

I Love (Downtown) L.A.: Going Beyond (500) Days of Summer

Once upon a time, L.A. was known for its newness. Anything that went back a generation or so (The Brown Derby, The Ambassador Hotel, Pickfair) was bound for the wrecking ball. Today, fortunately, there are groups around – like the invaluable L.A. Conservancy -- that will put up a fight to save the past. I’m especially enthralled by the old Downtown buildings now being transformed by imaginative developers and conservationists into funky living spaces.

One of my favorite recent films, (500) Days of Summer, is a rueful comedy about love gone awry, set entirely among those who live and work in L.A.’s downtown. But if (500) Days of Summer glorifies the modern cityscape, as well as such classic architectural wonders as the Bradbury Building (1893), it does not much stray into the area I explored this weekend, an industrial zone now coming to be called the Arts District. Some sections of the district, like a building at Mateo and Industrial Streets that was once home to the National Biscuit Company, now house elegant lofts designed to attract hipsters with fat wallets and a taste for the finer things. That’s why chic cafes are starting to abound. I slurped a fine latte at Handsome Roasters, an espresso joint so sincere that tea is banned from the menu, along with any add-in other than the organic whole milk they favor. Want a spoonful of sugar? Fuggedaboudit!

Though the dining is becoming high-end on Mateo Street, the area still boasts the vast spaces and graffiti-scarred walls that film crews are looking for. L.A.Conservancy's guide to this vicinity points out the Nate Starkman and Son Building, a cavernous brick structure from 1908, where the final episode of House was shot. Nearby Palmetto Street often stands in for San Francisco and other far-flung locales. And a former meat-packing plant is now a popular filming venue called Willow Studios, for those in need of a jail, a meat locker, a machine room, or a functioning bar.

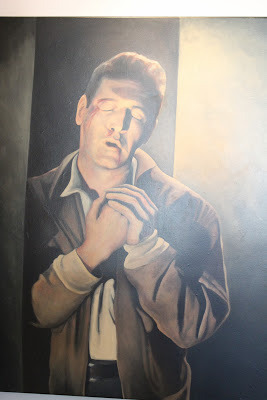

Slightly further north, Traction Avenue proudly offers gallery and living space to a number of working artists. These folks don’t expect – and can’t afford – the amenities that the Biscuit Company Lofts denizens require. You know, things like elevators to reach a flat that has terrific natural light, a great view, a rudimentary kitchen, and not much else. At the Southern California Supply Company Building at Traction and East Third, painter and assemblage artist A.S. Ashley is suffering from a badly broken ankle (the result of a surfing mishap), so he can barely leave his fourth-floor walk-up to enjoy the burgeoning street-life below.

I was impressed by how Ashley incorporates Hollywood into his aesthetic view of the world. His walls are hung with giant depictions of intense cinematic moments, like Paul Newman cradling his broken fingers in The Hustler and young Billy Mumy demonstrating his deadly powers in a famous episode of The Twilight Zone. I appreciated the humor of Salvador Dali painting Bugs Bunny, as well as the morbid Nazification of the ventriloquist’s dummy from Magic.

Back in the day, this area was an important rail freight center. When Roger Corman was shooting Little Shop of Horrors, cronies Chuck Griffith and Mel Welles paid a Southern Pacific crew two bottles of Scotch to back a locomotive away from actor Bobbie Coogan, who was lying on the track. They’d later print the shot in reverse to simulate Coogan (playing a drunken tramp) being run over by the train. The next day, Welles told me, Twentieth Century-Fox paid the railway company $15,000 to perform the same service.

photos by Bernie Bienstock

Published on November 12, 2013 13:21

November 8, 2013

“Enough Said”: For Those Who Can’t Leave Well Enough Alone

I love the work of Nicole Holofcener. Before this year’s Enough Said, she hadn’t made many films. But as a writer-director she has the uncanny knack of capturing life as it’s lived, especially by not-so-young women who lack self-confidence. And really, don’t we all?

Holofcener, daughter of an artist and a set-decorator, graduated from NYU film school, then worked on Woody Allen’s Hannah and Her Sisters. In her own films, she’s a miniaturist, adept at painting the nuances of small-scale social interaction. I didn’t see her debut feature, Walking and Talking (1996), but she had me at Lovely & Amazing, her 2001 dramedy about a mother and three daughters, one of whom (the adorable Emily Mortimer) agonizes horribly over her failure to measure up to society’s standards of beauty. I found Friends with Money (2006) less interesting. But Enough Said dispels all doubts about Holofcener’s talent. Here’s a social comedy that’s both hilariously funny and touchingly real.

The all-important female lead is Julia Louis-Dreyfus at her most expressive. She plays a divorced mom at a pivotal moment: her daughter is about to leave for college, and she’s not feeling so good about going it alone. Playing opposite her is James Gandolfini, that great bear of a man who, sadly, passed away just before the film’s release. They meet, are drawn together by what they have in common, then are pulled apart by forces that count for more than they should. I’m trying not to spoil the pleasures of the film’s deceptively simple plotting. Suffice it to say that this is a movie about romantic compatibility, about letting go of (almost-)grown children, and about having the courage of your convictions. The triumph of Holofcener’s screenplay (as well as her on-target casting choices) is that not a single line sounds written. For all we know, these are real – though familiar-looking -- people up there on screen, speaking their minds, for better or for worse.

I also reveled in the fact that Enough Said is such a very L.A. movie. (In this, it reminds me of another personal favorite, The Kids are All Right. To be honest, I remembered this as a Holofcener film, until I discovered it was made by another gifted miniaturist, Lisa Chodolenko.) Holofcener grew up in New York, but for years she’s lived with her two sons in Venice, California. Which is why, of course, she has the geographical details down pat. Hers is not the L.A. of glitz and movie stars, nor of high-rises and urban squalor. Louis-Dreyfus, tooling around in her snappy blue Prius, is every inch the Westside mom. The various houses in the film all look genuinely lived-in, and I feel I’ve been in most of them at one time or another. The restaurants – Lilly’s on Abbott Kinney Blvd. and Guido’s just off Bundy – are places I know. The characters’ professions seem right: she’s a masseuse who makes house calls, he heads some sort of TV archive. Then there’s the key character played by a Holofcener regular, Catherine Keener. She’s the most L.A. sort of successful poet, one who pals around with Joni Mitchell and tends a backyard herb garden that’s to die for.

Holofcener gets the SoCal details so right that it’s jarring on the rare occasion when a location doesn’t make sense. Like the scene of Louis-Dreyfus’s daughter leaving for Sarah Lawrence: that unfamiliar terminal, supposedly at LAX, was definitely a distraction. Still, the mother-daughter parting seemed poignantly real, and reminded me of a great Holofcener quote: “It's harder to take care of kids than it is to make a movie.” ‘Nuff said.

Published on November 08, 2013 15:15

Beverly in Movieland

I write twice weekly, covering topics relating to movies, moviemaking, and growing up Hollywood-adjacent. I believe that movies can change lives, and I'm always happy to hear from readers who'd like t

I write twice weekly, covering topics relating to movies, moviemaking, and growing up Hollywood-adjacent. I believe that movies can change lives, and I'm always happy to hear from readers who'd like to discuss that point.

...more

- Beverly Gray's profile

- 10 followers