Beverly Gray's Blog: Beverly in Movieland, page 120

June 3, 2014

Food for Thought about “Chef”

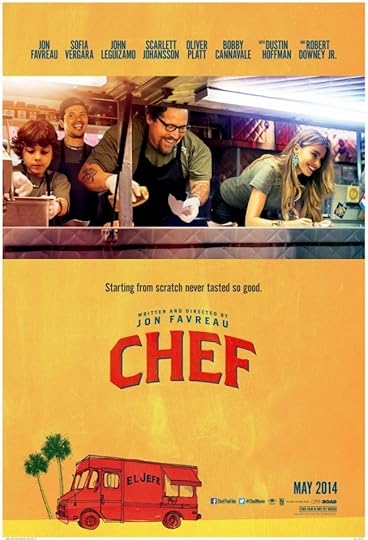

Every culture’s cuisine includes some kind of stew. I’d define a stew as a big pot full of varied ingredients: meats, vegetables, some liquid, plus herbs and spices. You let it simmer for a long time, then serve. It’s not the most artistic of dishes, but it goes down easy. And it makes for a great analogy to Jon Favreau’s new indie, Chef.

Chef, a low-budget tribute to Favreau’s obvious passion for food, stirs together a great many ideas into one long-ish film. It’s about the excitement of food preparation, and about the contrast between trendy fine dining and the heartier fare that represents regional cuisine at its finest. It’s about the power of food critics to make or break a star chef (think Ratatouille), and about an iconoclast’s determination to forge his own path (think every rugged-individualist hero since Hollywood’s Golden Age) . It’s about SoCal foodie culture, and about cooking as a form of theatre. And it’s about a father who learns he should not be too busy to allow his young son into his life. (Is there a recent movie out there that does NOT include a kid resentful of his divorced dad’s workaholic ways?)

Favreau first made his name as the romantic lead in Swingers, a modest comedy he wrote for himself and buddy Vince Vaughn. Since then, he has mostly been known for directing hits like Elf and the decidedly big-budget Iron Man franchise. In Chef, he’s again thinking small, but has convinced a hip array of Hollywood favorites to come aboard. In the world of the movie, the faint-hearted restaurateur who clashes with Favreau’s Chef Carl Casper over the evening’s menu is played by Dustin Hoffman. Scarlett Johansson (in a fetching Bettie Page wig) is on the restaurant staff, as are line-cook John Leguizamo and sous-chef Bobby Cannavale. The very toothsome Sofia Vergara is Casper’s ex-wife (whose own successful career is hinted at but never explained). And her previous ex-husband, who becomes Casper’s unlikely benefactor, is Iron Man himself, a very funny Robert Downey Jr. Each luminary of course requires some memorable screentime, one reason why Favreau’s script seems so disjointed and so long.

Another star of the film, one who shines brightly during its closing credits, is L.A. foodie legend, Roy Choi. It was Choi, a Korean immigrant, who kicked off Southern California’s food truck craze when he started tooling around L.A. in his Kogi truck, serving up Mexican-style tacos and burritos stuffed with garlicky Korean barbecue. Each evening he’d tweet out his various stops, and hipster cognoscenti would jump into their cars, waking up their taste buds for a late-night nosh. Choi coached Favreau on his cooking skills, then functioned as his on-set food consultant. The movie’s plot line, one that shows Chef Carl walking away from the haute-cuisine world to sell Cuban sandwiches from a food truck, is a tribute to Choi’s own career path. As the final credits role, you can see Choi applying his personal TLC to perhaps the world’s most gorgeous grilled cheese sandwich. Yum!

The finished movie is a testament to the joy of simple but sumptuous cooking, and also to the way the Twitterverse has transformed our lives. The film’s big crisis starts with a flame war between restaurant critic Oliver Platt and the Twitter-novice chef. When what he thinks is a private tweet goes viral, chaos ensues. But all is not lost: as the movie shows, social media can make a career as well as break one. That’s something, of course, that Roy Choi has known for a long time.

Published on June 03, 2014 12:45

May 30, 2014

Rosemary’s Baby, Reborn

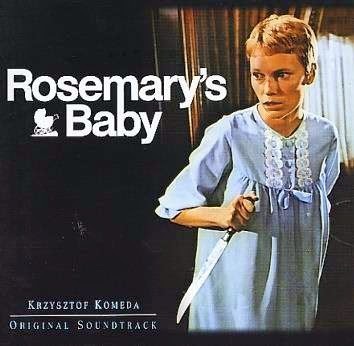

So they’ve had the guts to remake Rosemary’s Baby as a miniseries. And from what I’ve heard, it’s pretty good. The setting has been moved to Paris, a city which has its visually spooky side. And the acting is supposed to be fine. But I can’t imagine this Rosemary’s Baby ever having the impact of Roman Polanski’s 1968 original.

Rosemary’s Baby of course started life as a novel by Ira Levin. It was so original, and so audaciously scary, that publisher Bennett Cerf of Random House considered it perhaps TOO suspenseful. Maybe, he suggested, Levin should make clear that the Satanic takeover at the novel’s end was all just a bad dream.

The novel was a 1967 bestseller, and when the film version debuted the following year, it too quickly became a sensation. Partly the time was ripe: moviegoers in 1968 had (in the words of Shakespeare’s Macbeth) “supped full with horrors.” Many remembered the assassination of President John F. Kennedy in 1963. When the film was released on June 12, 1968, only two months had passed since the slaying of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. in Memphis, precipitating nation-wide riots. And Rosemary’s Baby opened just six days after Robert F. Kennedy was gunned down in Los Angeles. America, it seemed, was ripe for accepting a world being usurped by demonic powers.

And director Polanski was uniquely qualified to handle such strong material. The shocking slaughter of his wife Sharon Tate, along with their unborn baby, by members of the Manson clan was still more than a year off. But Polanski was also a Holocaust survivor. In the late 1930s, as a small child, he was living with his family in the Polish city of Krakow. When the Nazis moved in, he was forced out of school and into a Jewish ghetto. His parents were taken away and killed; he himself survived by pretending to belong to a Roman Catholic family. Later he roamed the countryside on his own, trying to elude German soldiers taking potshots at the fleeing boy. So Polanski had, along with impressive filmmaking skills, a strong personal identification with a God-is-dead world.

I’ve not always been a fan of Mia Farrow, and her current-day behavior strikes me as more than a bit batty, but she plays the passive, put-upon Rosemary with stunning conviction. As much as her acting it’s her physical presence that sells the story. She’s so pale, so thin, so apparently fragile: the lopping off of her blonde tresses into a very short Vidal Sassoon bob midway through the film completes our sense of her as the ultimate victim. (Frankly, I doubt that the statuesque Zoe Saldana could ever spark our imagination in the way that the cadaverous Farrow does.) I don’t love everything about the movie -- the big Satanic rape scene is definitely heavy-handed – but the sinister presence of John Cassavetes, Sidney Blackmer, and the Oscar-winning Ruth Gordon can’t be beat.

Much of the power of Levin’s story comes from the mysteries we associate with pregnancy. Every woman who’s been with child knows how easy it is to be overawed by the strange things happening inside her. Body parts change size and shape. Emotions swing wildly. Doctors and other traditional allies sometimes don’t seem to have her best interests at heart. She’s eating (and sleeping and breathing) for two, but the final outcome remains very much in question. Until, of course, the baby arrives and demands to be loved. That’s why films about pregnancy (like Rosemary’s Baby and even a Roger Corman cheapie like The Unborn) grab hold and don’t let go.

This post hails the arrival of Mila Danielle Grayver on May 19, 2014, following a perfectly uneventful pregnancy. Family members are thrilled to welcome Mila into their inarguably normal home, which is in Manhattan Beach, not Manhattan – and therefore nowhere near the Dakota.

Published on May 30, 2014 10:31

May 27, 2014

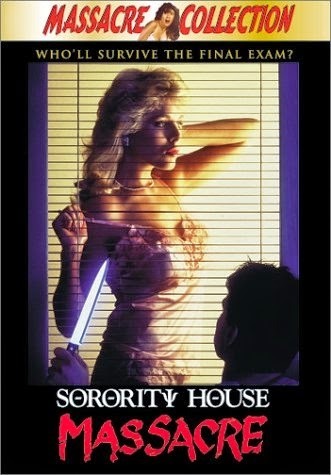

“Sorority House Massacre” Hits Home

The horrific events in Santa Barbara that left six young people dead and many others wounded have hit me hard. The killer began his rampage by slaughtering his college roommates. But his real target – spelled out in a series of chilling YouTube videos -- was clearly the pretty, popular co-eds who lived at the sorority houses of the University of California’s Santa Barbara campus. In my Roger Corman days, I worked on Sorority House Massacre II. But I never thought the events of that slasher flick would be played out in real life.

The classic “girls in jeopardy” films, which date back to Halloween in 1978, feature plucky young women menaced in nightmarish fashion by a male intruder. A “final girl” always survives to tell the tale, but not before many attractive females have been brutally slaughtered. Personally, I’ve contributed to the scripts of Concorde’s Slumber Party Massacre II and III, as well as to Jim Wynorski’s quickie take on Sorority House Massacre, not to mention his office-tower follow-up, Hard to Die. Wynorski’s involvement in the latter two films assured the viewer of buxom young lovelies being terrorized in their undies. But mostly Roger Corman mandated that his films in this genre be written, produced, and directed by women. His reasoning: if women called the shots, he’d be able to swear that the on-screen carnage was justified, because it simply reflected the fears felt by post-adolescent girls facing their budding sexuality.

Despite this clever self-justification, the fans of the Slumber Party and Sorority House series are largely male. I suspect what they like is the sight of nubile young women, scantily clad, screaming in horror as they flee from a relentless assassin. There are two Facebook groups I know of that celebrate these films. I’ve communicated with some of their members, and they’re hardly rooting for harm to befall the films’ female protagonists. In fact, they often strongly identify with the damsels in distress. Said one, “Women-in-jeopardy films as a whole appealed to me as a teenager because I was associating myself with the heroine of each film. I wasn't enjoying watching her get tormented. I was enjoying watching her survive. Overcoming the odds.” These female characters, he said, were “going through the worst time of their life, but they were coming out on top. Battered, bloodied and bruised, they were still beating the bad guys.”

And yet . . . a key component of all of these slasher films is that bad guy, someone who hates women and wants to make them suffer. He’s so attractive to viewers, in his dark and demonic way, that I’ve seen lively debates about which Driller-Killer (from Slumber Party Massacre I, II, or III) fans prefer. The killer’s backstory varies from film to film, but none seems much different from Elliot Rodger, who announced in a 141-page diatribe that “I will punish all females for the crime of depriving me of sex. . . . I cannot kill every single female on earth, but I can deliver a devastating blow that will shake all of them to the core of their wicked hearts.” Rodger’s relentless anger and self-pity are hideous to contemplate, but I have the sinking feeling that somewhere out there someone is incorporating him into the script for a new slasher extravaganza. According to the newspapers, Elliot Rodger’s life was one of Hollywood privilege. Thanks to family connections, he hobnobbed with celebrities, went to the swankiest schools, drove a BMW on his killing spree. So sad that he went Hollywood by leaving a trail of blood.

Published on May 27, 2014 12:26

May 23, 2014

The Normal Heart: How Bruce Davison Found His Valentine at Christmas (with my help)

Scheduling HBO’s production of Larry Kramer’s The Normal Heart for Memorial Day Weekend makes perfect sense: the play is a memorial to those dead and gone in the early days of the AIDS epidemic. Kramer, who was surrounded by dying friends in the early 1980s, wrote The Normal Heart to galvanize the gay community, the health bureaucracy, and the public at large. It debuted at New York’s Public Theater in 1985, creating a major stir. None other than Barbra Streisand bought the film rights, hoping to play the key role of the female doctor who sympathetically confronts the crisis. But for ten long years she couldn’t find funding. Now, at long last, HBO will broadcast a full-length version on Sunday, May 25, with Julia Roberts as the doctor, and Mark Ruffalo filling the role of Kramer’s own alter ego, activist Ned Weeks.

I saw The Normal Heart in a tiny L.A. theatre, the Las Palmas, soon after it played New York. The cast featured Oscar-winner Richard Dreyfuss as Weeks and a pre-Misery Kathy Bates as the doctor. But the actor I’ll never forget was Bruce Davison, who dramatically succumbed to AIDS onstage, mere inches from those of us in the front row.

Davison has had a long movie career, starting as a teenage rapist in 1969’s Last Summer and spanning everything from Willard (1971) to Short Cuts (1993) to X-Men (2000). For Longtime Companion, the landmark 1989 feature film about the impact of the AIDS epidemic on a circle of friends, he won many awards, and was nominated for a Best Supporting Actor Oscar. But that was still in the future when I talked to Bruce during the run of The Normal Heart.

I was then writing for the Los Angeles Times. Drama editor Dan Sullivan had charged me with a series of articles tied to various holiday periods. For Christmas, he suggested I ask several actors how they felt about appearing on stage during a season when everyone else was home trimming the tree. It was a thrill to chat with Hume Cronyn and Jessica Tandy, in residence at L.A.’s Ahmanson Theatre in Foxfire. I loved the opportunity to meet Nancy Kwan too. But when I spoke to Bruce Davison, the conversation ended up changing HIS life. Here’s how it happened.

Bruce, a lively talker, told me he was delighted that The Normal Heart would be closed on both Christmas Eve and Christmas Day. He viewed his brief holiday from the show as “24 hours out of the trenches. I’d like to be with someone and share it. If you know of a beautiful woman with a turkey . . . .” Continuing the interview, I alluded to flame-haired actress Lisa Pelikan, who had told me she was glad to be working at Christmas to distract from a recent break-up. Bruce was immediately interested: they’d never met, but she was exactly the kind of beautiful woman he had in mind. It was none of my business, certainly, but I encouraged him to look her up. From what I later heard, he bought a ticket to her play, then rushed backstage afterwards, exclaiming, “I’ve heard you’re single!” When I saw Bruce a few weeks later, he said, “Thank you for Lisa.”

They wed on July 4, 1986 (I received a formal announcement), and eventually had a son named Ethan. Of course, in Hollywood nothing good ever lasts. Bruce and Lisa divorced after twenty years, and are now both attached to others. Still, I treasure the memory of the time that I, a mild-mannered reporter, got to play Cupid.

Published on May 23, 2014 14:20

May 20, 2014

What’s in a Name?: Women Embracing Their Birthright

In Hollywood, everyone wants to make a name for himself. Or, of course, herself. Many mid-level performers keep tinkering with the spelling of their names in hopes of somehow rocketing to stardom. And it’s not just the unknowns: in 1971 pop singer Dionne Warwick, no slouch in the fame and fortune department, was advised by her astrologer to add a final “e” to her surname to encourage good psychic vibrations. (It didn’t work, and she went from “Warwicke” back to her original name a few years later.)

Then there are those celebrities who wed their co-stars and feel a sweet sense of obligation to take their husbands’ names as their own. If they’re smart, they hyphenate. When Farrah Fawcett married TV star Lee Majors, she became Farrah Fawcett-Majors. I can also think of Meredith Baxter-Birney (during her marriage to David Birney), Rebecca Romijn-Stamos (married to John Stamos), and Joanne Whalley-Kilmer (who fell for Val Kilmer on the set of her first movie, Willow). None of these marriages lasted, and the hyphens quickly disappeared, with no career harm done.

By contrast, comedian Roseanne Barr variously billed herself (depending on her marital status) as Roseanne Arnold, or Roseanne Thomas, or just plain Roseanne. And I remember wags poking fun at Elizabeth Taylor by referring to her as Elizabeth Taylor Hilton Wilding Todd Fisher Burton Burton Warner Fortensky. Funny: much-married men don’t get mocked in the same way.

Which I’m sure has occurred to Susan Henry, author of the fascinating Doris Fleischman was for me an especially interesting case. She was the dutiful daughter of a strict father, and the man she married was equally controlling. It was husband Bernays who decided she should hold onto her own family name after they wed in 1922. When they checked into New York’s Waldorf-Astoria for their honeymoon, press releases trumpeted that by signing the register in both names they were making hotel history. (It wasn’t true, but Bernays was a master at self-promotion.)

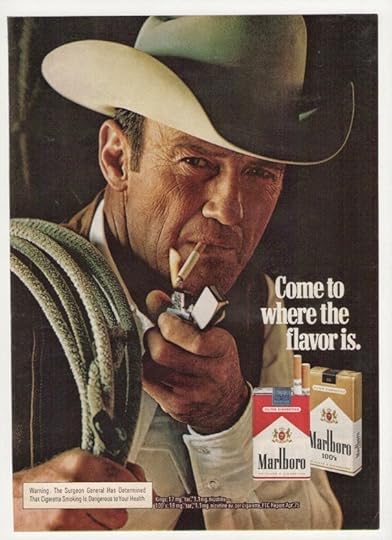

Fleischman worked closely with Bernays at the public relations firm that bore his name alone. In one respect, I wish she hadn’t been quite so successful. One of their best clients was the American Tobacco Company. As a smoker herself (despite her husband’s objections), Fleischman was instrumental in figuring out how to reach others of her gender. An early ad encouraging women to “reach for a Lucky instead of a sweet” paid off by appealing to the weight-conscious. Next, the goal was to persuade bold young ladies to light up in public places. This campaign (which preceded Virginia Slims’ “You’ve come a long way, baby” ads by many decades) emphasized cigarettes as “torches of freedom” for liberated females. Cigarette ads, as we all know, generally do their work far too well. Eric Lawson, featured as a rugged cowboy in many Marlboro commercials, died this past January of lung disease at age 72. That makes the fourth former Marlboro man brought down by smoking-related illness. I wish Doris Fleischman had concentrated on names, not smokes.

Published on May 20, 2014 08:58

May 15, 2014

Paul Robeson in Black and White

So Donald Sterling is once again dominating the airwaves, insisting that he’s not a racist. Personally, I’d love to imagine Sterling in the same room with the late Paul Robeson. Not that Robeson was a pro basketball player. But I suspect he could have been. Paul Robeson could do just about everything well. (Except, maybe, stay true to his marriage vows.) In the 1930s he became an international film star, then walked away to champion the plight of his fellow black Americans, along with working stiffs everywhere.

I’m mesmerized with Robeson right now because I just saw Daniel Beaty perform his one-man tribute, The Tallest Tree in the Forest. Robeson, it seems, was indeed tall . . . and handsome . . . and fearless . . . and extremely complicated. The son of a slave who escaped and entered the ministry, Robeson was born in genteel Princeton, New Jersey in 1898. In high school he was a four-sport athlete, but entered Rutgers University on an academic scholarship.

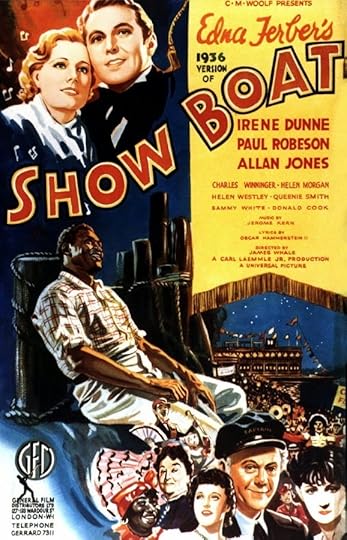

While at Rutgers he used his thrilling baritone voice to earn extra money. Meanwhile, he excelled on the debate squad, became a football All-American, and graduated as class valedictorian. Somehow he then managed to play NFL football while also attending Columbia University’s School of Law. But he ended his law career abruptly because of the racism all around him: he was not welcome in courtrooms, and one secretary refused to take dictation from a black man. Instead, encouraged by his loyal wife Eslanda, Paul Robeson chose to concentrate on music and the theatre. During the era of the Harlem Renaissance, he starred in several ground-breaking plays, including Eugene O’Neill’s All God’s Chillun Got Wings and a popular revival of The Emperor Jones. He and Essie then relocated to London, where he was one of the first black men ever to play Othello. (His long affair with his Desdemona, Peggy Ashcroft, rocked his marriage, not for the first time. It managed to survive, but entirely on his terms.) As Robeson’s stature in Europe grew, he began making films. The cinematic version of The Emperor Jones (1933) was the first major movie ever to star an African American male: in 1999 it was selected for inclusion in the National Film Registry. Robeson was also top-billed for his role as a native chieftain in Sanders of the River (1935), a English-made drama set in Africa. The finished film is a paean to British colonialism, with Robeson and the other African characters happily subservient to Commissioner Sanders, the Great White Father who solves all their problems. So appalled was Robeson when he saw the final cut that he fought to halt the film’s release. Most famously of all, Robeson was featured in the 1936 film version (directed by James Whale) of Kern and Hammerstein’s legendary Show Boat, singing the immortal “Ol’ Man River.” Today the staging of that number looks crude indeed, but the force of Robeson’s presence still lingers. “Ol’ Man River” became his signature song, to the point where he changed the famous lyrics to reflect his own fighting spirit. And fight he did, embracing the Soviet Union for outlawing racism, then butting heads with the House Un-American Activities Committee. Robeson had always championed Jewish causes, both at home and abroad, so one moment in Beaty’s play shocked me. Although Russian-Jewish friends, cruelly persecuted by Stalin’s regime, pleaded with him to speak out, he refused to denounce the USSR while on American soil. One more contradiction in a life that held many. But Paul Robeson was an enigma, and he just kept rollin’ along.

Published on May 15, 2014 14:03

May 13, 2014

Breakfast (and a Movie) at Tiffany’s

On May 4, I thought about Audrey Hepburn, who was born on that date in 1929. If she had lived, she would have just turned 85. That’s hard to imagine, given what a charming gamine she made in films like Roman Holiday (1953), Sabrina (1954), and Funny Face (1957). Of course she got older, and skillfully took on mature roles in Two for the Road (1967) and Robin and Marian (1976). But Hepburn had no opportunity to truly become elderly on screen. She left us in 1993, at the age of 63.

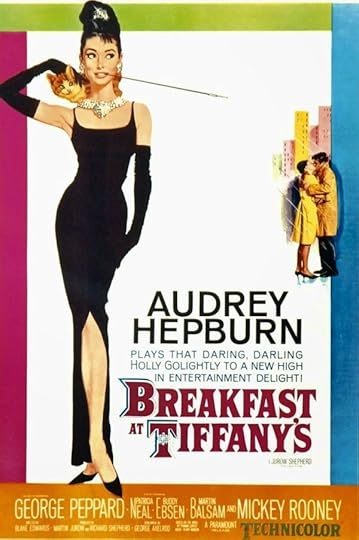

One of Audrey Hepburn’s classic performances came in the 1961 Blake Edwards film version of Truman Capote’s Breakfast at Tiffany’s. As party-girl Holly Golightly, who stays afloat in New York City with a little help from her (male) friends, Hepburn is both hilarious and heart-breaking. Capote, though, was not pleased. The story as he envisioned it called for a Holly who was less elegant and more earthy. To Capote, Marilyn Monroe would have been perfect casting. (And he also envisioned himself playing Holly’s confidante, the male lead.)

Much of what I know about Breakfast at Tiffany’s comes from a fascinating little volume that appeared in 2010. Sam Wasson (who has since gone on to write a major biography of Bob Fosse) is the author of Fifth Avenue, 5 A.M.: Audrey Hepburn, Breakfast at Tiffany’s, and the Dawn of the Modern Woman. Wasson’s book chronicles the making of the film, and also reveals how vital it was in changing the public perception of women’s behavior, at a time when sexual mores were starting to change. As he writes, Breakfast at Tiffany’s “rerouted the course of women in the movies, giving voice to what was then a still-unspoken shift in the 1950s gender plan. There was always sex in Hollywood, but before Breakfast at Tiffany’s, only the bad girls were having it.“

The challenges for Paramount Pictures when approaching the original material were manifold: Capote had given the world “a novel with no second act, a nameless gay [male] protagonist, a motiveless drama, and an unhappy ending.” After much angst, the screen version evolved into a romantic comedy that faded out on a happily-ever-after kiss in the rain, with “Moon River” swelling in the background. Paramount execs solved the problem of the book’s gay protagonist by turning George Peppard’s writer-character into a red-blooded American male. Holly Golightly, as repurposed for the film, was less a high-class hooker than an adorable kook. It helped immensely, of course, that Audrey Hepburn hardly connoted sexuality in a way that Marilyn Monroe assuredly did. Reading between the lines, we knew that Holly slept around—and earned her daily bread by so doing. But mostly Hepburn’s Holly was childlike and fun, with a child’s wistful innocence underneath. And Peppard’s Paul Varjak was made a gigolo of sorts, as a clever way of distracting us from Holly’s own sexual side.

Wasson has much more to say about Breakfast at Tiffany’s. About, for instance, the inspired teaming of veteran lyricist Johnny Mercer with newcomer Henry Mancini (“Together they were kindness incarnate, and they melted as easily as butter on mashed potatoes”). About the impact of Givenchy’s little black dress, which—as worn by Hepburn—gave women on a budget the freedom to look bold and sophisticated without seeming flashy. The movie feels modern, except in one department: Mickey Rooney’s obnoxious caricature of a buck-toothed Japanese neighbor, played strictly for guffaws. Director Blake Edwards eventually apologized for this lapse in taste, which rubbed many Asians the wrong way. Like Truman Capote, the great Akira Kurosawa was most displeased.

Published on May 13, 2014 13:57

May 9, 2014

He Had a Little List: How Carl Laemmle Became Hollywood’s Oskar Schindler

The Rialto school district, in California’s Inland Empire, is now under fire for an English class assignment required of all eighth-graders. The assignment? To write research papers debating whether the Holocaust actually happened. The “evidence” placed at students’ disposal included links to sites of Holocaust deniers who dismiss the murder of six million Jews as pure fable, a worldwide hoax designed to advance Jewish interests.

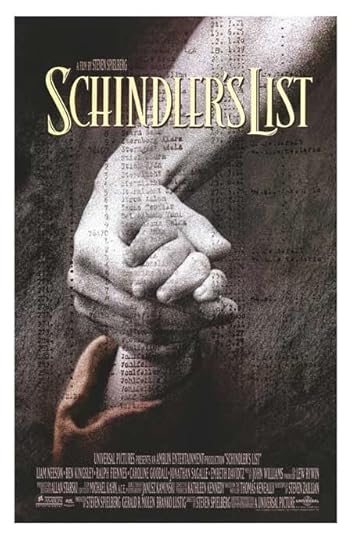

Today’s Hollywood has no room for Holocaust deniers. Countless feature films have been made on the subject, dating back to Orson Welles’ The Stranger (1946), which incorporated actual concentration camp footage into its plot. Schindler’s List was of course a global blockbuster in 1993, and documentaries that touch on the Holocaust period are perennial Oscar winners. But back in the 1930s, when the Nazis were tightening their grip on Europe, Hollywood studio bosses were reluctant to jeopardize their profits by speaking out against the new German regime. Though the heads of most major studios were themselves Jewish immigrants from Eastern Europe, they preferred to overlook the anti-Semitic rhetoric coming out of Deutschland. Psychologically, says film historian Neal Gabler, this was their way of advertising themselves as true-blue Americans, part of the cultural mainstream that had little interest in protecting an ethnic minority in a foreign land.

Gabler should know. As the author of the classic An Empire of Their Own: How the Jews Invented Hollywood, he’s well aware of how a Hollywood Jew like MGM’s Irving Thalberg could visit Germany in 1934 and shrug off the rising tide with a quip: “Hitler and Hitlerism would pass; the Jews will still be there.” Even though Thalberg and others suspected a bloodbath was coming, they went on with the business of show business. (Recent books by Thomas Doherty and Ben Urwand accuse the moguls of actually collaborating with Nazi higher-ups in order to safeguard Hollywood interests.)

Carl Laemmle, though, was a different story. Gabler says as much in a recent NewYork Times piece, written at the behest of a man whose father owed his life to Laemmle’s intervention. The jovial Laemmle, known throughout Hollywood as Uncle Carl, ran Universal Studios for the first twenty years of its existence. A native of Laupheim, Germany, he quickly spotted the dangers ahead when the German première of Universal’s anti-war All Quiet on the Western Front was disrupted by Nazi hooligans, after which Universal’s German rep (a Laemmle relative) was dragged out of his bed for questioning. Determined to save his large extended family from the Nazis, Carl compiled a list, then began pulling strings to guarantee their safe passage to America. Very soon other German Jews were appealing to him for help, and the list grew longer.

By signing affidavits for hundreds of Jews, Laemmle was guaranteeing them financial as well as moral support once they landed on American shores. Gabler details the lengths to which he went in securing the future of those he saved. This was an expensive proposition. And it was not made easier by the fact that two successive American consuls in Stuttgart made bureaucratic demands seemingly designed to thwart Laemmle’s efforts. Perhaps that’s why, as war approached, Laemmle’s health deteriorated. On September 24, 1939, just after Hitler invaded Poland, he was dead at age seventy-two.

One L.A. branch of the Laemmle clan has run a chain of art-houses for decades. When I last visited the Royal on Santa Monica Boulevard, I discovered a kind of memorial wall dedicated to family history. There I saw evidence of Carl Laemmle’s good deeds, including a heartfelt letter from one of his beneficiaries. Thanks, Uncle Carl.

Published on May 09, 2014 11:39

May 6, 2014

Pat Nixon and Winnie Davis: Icons of Womanhood

It’s common wisdom that Richard Nixon lost the presidency to John F. Kennedy in 1960 because he didn’t know how to handle television. During their first televised debate, Kennedy appeared tan and relaxed, while Nixon’s sweaty forehead and five o’clock shadow made him look disreputable. But as author Will Swift points out in Pat and Dick , there were times when Nixon himself turned the new medium of television into brilliant political theatre. Swift kicks off his portrait of the Nixon marriage by describing the night of September 23, 1952. Nixon, campaigning to become Dwight D. Eisenhower’s vice president, had been accused of taking inappropriate monetary gifts from campaign donors. With his candidacy called into question, he decided to book a live broadcast to the nation. The stage at Hollywood’s El Capitan Theater was dressed to look like the den of a middle-class family home. Dick Nixon, seated at a desk, proclaimed himself innocent of having received anything but Checkers, the beloved family cocker spaniel.

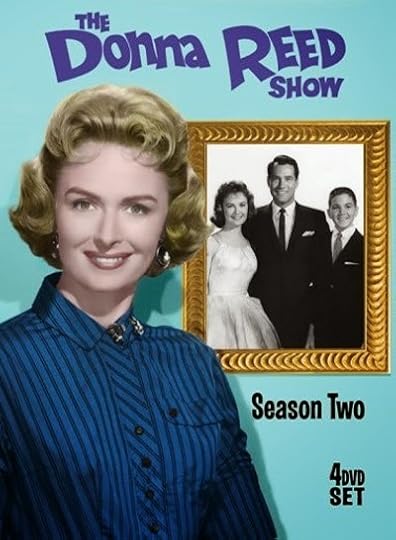

During a speech that made Checkers a household name and helped Nixon surge in popularity, Pat sat silently, loyally, at her husband’s side. For her pains, she won the respect of an American public that believed it was a wife’s duty to stand (or at least sit) by her man. Patricia Ryan Nixon—who before marriage had been a school teacher and a sometime movie actress—knew she had to live up to the Fifties ideal of womanhood. It was her responsibility to raise the children and keep the home fires burning while her mate went off to joust with the outside world. In 1960, says Swift, Americans had not yet fallen in love with the patrician Jackie Kennedy. “But Pat Nixon was as familiar to them as television actress Donna Reed, and as much admired.” Reed, of course, was the star of a long-running TV sitcom (1958-1966) portraying an idealized American family guided through life by Mom’s wit and wisdom.

Swift suggests that being Dick Nixon’s helpmeet was not the easiest of jobs. She was a private woman and a proud one. As much as Pat believed in her husband's brilliance and his destiny, being cast as a symbol (and publicly ridiculed as “Plastic Pat” by her husband’s detractors) could not have been pleasant for her.

Oddly, I started thinking about Pat Nixon after reading the biography of a woman who never became a wife and mother. Heath Hardage Lee is the author of Winnie Davis: Daughter of the Lost Cause. It’s a scholarly book that has attracted some Hollywood interest, and I can see why. Winnie was the youngest child of Jefferson Davis, the president of the Confederacy. Born in the darkest days of the Civil War, she grew up to find she was expected to serve as a symbol of the Old South. Solemn and virginal, dressed all in white, she appeared before Southern veterans’ groups like a sweet apparition, lending her angelic touch to the nostalgia they felt for the Dixie of ante-bellum days. As an image of Southern womanhood, Winnie was far less Scarlett O’Hara than sweet, sad Melanie, and the old soldiers loved her for it.

But Winnie was also a flesh-and-blood young lady, one who fell for exactly the wrong kind of man. So loud was the clamor from her Southern admirers that the engagement got called off. She found some happiness in, of all places, New York City, where she worked as a writer and lived an independent life. But, ironically, her obligations to the Lost Cause did her in: by age 34 she was dead. As Pat Nixon also knew, being a symbol is hard work.

Will Swift will appear on my panel, “Getting the Family on Board,” at this year’s conference of the Biographers International Organization (BIO), to be held in Boston on May 17. The public is cordially invited.

Published on May 06, 2014 11:37

May 2, 2014

Lethal Outcome: Aileen Wuornos and Executions, Hollywood-Style

That grizzly botched execution in Oklahoma has reminded me of all the movies in which central characters are put to death by the state. Usually the actors involved win Oscar nominations for their troubles. Susan Hayward, who was marched to the gas chamber in 1958’s I Want to Live, took home a Best Actress statuette for her emotional performance. Michael Clarke Duncan, playing a gentle giant who goes willingly to the electric chair in 1999’s The Green Mile, was nominated as Best Supporting Actor. Four years earlier, Sean Penn’s rapist-character died by lethal injection in Dead Man Walking, after cleansing his soul by confessing his crimes. Penn was Oscar nominated, though it was Susan Sarandon who won the big prize for this artfully crafted drama. Playing a real-life death-penalty opponent, Sister Helen Prejean, she put forth arguments against state-sanctioned killing that still linger in my brain.

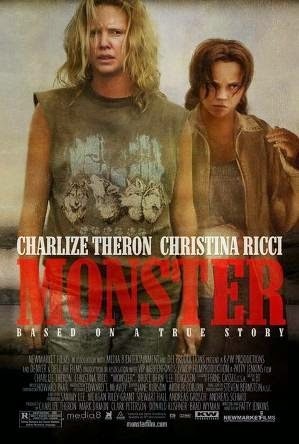

Then there was Aileen Wuornos. Charlize Theron nabbed the 2003 Oscar for transforming herself from a glamour-girl to a scruffy, raw-boned hooker who killed seven men before dying in Florida’s death chamber. The film version, called Monster, does not shy away from the brutality of Wuornos’s crimes. But it also creates sympathy for this self-appointed “first female serial killer” by playing up her victimization, both by the men who were her “johns” and by the female lover she was trying to impress.

My source for the real story of Aileen Wuornos is Lethal Intent, a recently re-released true-crime account by journalist Sue Russell. Russell, who has been investigating Wuornos’ life since her arrest in 1991, does not overlook the harsh events that shaped Wuornos’s world from childhood onward. But she is also well aware that Aileen was a pathological liar who would say anything to get attention. Early on, she bragged to a friend that “there’ll be a book written about me one day,” and she once tried to commission a ghost-written autobiography. Her real goal (emphasized in the movie’s opening voiceover) was to turn herself into a celebrity, maybe even a movie star. In prison, following her sensational arrest, she demanded recognition from her fellow inmates: “Do you know who I am? I’m Aileen Wuornos of television.”

There’s nothing wrong with dreams of glory, but Aileen seemed determined to turn herself into an avenging heroine. According to Monster, which takes Aileen’s court testimony at face value, she first killed in response to a brutal rape. The evidence, though, strongly suggests that her motive was robbery: she took possession of her victim’s cash and car, then concocted a dandy story to cover her misdeeds.

In one other key respect, the movie twists facts to ratchet up sympathy for its protagonist. In real life, Aileen’s lover was a cheerful, pragmatic lesbian named Tyria (or Ty). It was she who was to become the #1 witness for the prosecution, possibly in a frank bid to save her own skin. Monster transforms Ty from a hefty, feisty dame into the waiflike Shelby. As played by the petite and saucer-eyed Christina Ricci, Shelby is something of a sponge, petulantly demanding that Aileen provide her with good times and a house by the beach. In this version, Aileen kills repeatedly because she loves not wisely but too well.

For me, the most truthful moment in Monster is Aileen’s slaying of a Good Samaritan who thinks he’s stopped his car to help a lady in distress. Ironically, he’s played by Scott Wilson, one of the killers from 1967’s In Cold Blood. Yes, he was hanged at the end of that film. No Oscar nom, though. Sometimes you just can’t win.

Here’s Sue Russell’s frank response to Monster, first published in the Washington Post and now featured on her website, http://www.suerussellwrites.com

Published on May 02, 2014 12:02

Beverly in Movieland

I write twice weekly, covering topics relating to movies, moviemaking, and growing up Hollywood-adjacent. I believe that movies can change lives, and I'm always happy to hear from readers who'd like t

I write twice weekly, covering topics relating to movies, moviemaking, and growing up Hollywood-adjacent. I believe that movies can change lives, and I'm always happy to hear from readers who'd like to discuss that point.

...more

- Beverly Gray's profile

- 10 followers