Beverly Gray's Blog: Beverly in Movieland, page 117

September 12, 2014

Mel Brooks Gets His Hands Dirty (and other recollections of a Dynamic Duo)

Sounds like Mel Brooks, impish as always, has just given the finger to Hollywood. In honor of the Blue-Ray release marking the 40th anniversary of Young Frankenstein, Brooks was invited to embed his hand and footprints in the forecourt of Grauman’s Chinese Theater. (Its official name is now the TCL Chinese Theater, in recognition of its current ownership, but it will always be Grauman’s to me.) When Brooks arrived for the ceremony, he was wearing a fake extra digit, as a way of confounding future stargazing tourists. He happily conjured up for the press some visitor from Des Moines squealing, “Harry! Harry! Look, Mel Brooks has six fingers on his left hand!”

I’ve long enjoyed Mel Brooks’ genial zaniness, and Young Frankenstein, which the L. A. Times calls “a comic monsterpiece,” is a special favorite of mine. And I’ve been delighted with Brooks’ largely successful conquest of Broadway’s musical comedy genre, which can always use a boost. A family member once was squeamish about Brooks’ humorous glorification of Nazi Germany via the “Springtime for Hitler” aspects of The Producers. But he was completely won over by hearing Brooks explain that, as a Jew, he considered his mocking salute to Hitler and his thugs a public victory over the forces that had tried to annihilate his people. “It’s good to be the king,” as all Mel Brooks fans know. It’s certainly fair to call Brooks, now 88, the king of outrageous comedy on stage and screen. (Not to mention recordings: who of my generation can ever forget The Two Thousand Year Old Man?) But every king deserves a worthy consort, and I can’t talk about Brooks without paying tribute to his wife of 41 years, the late and very much lamented Anne Bancroft.

When I was newly pregnant with my first child, I was sitting in my doctor’s waiting room, feeling fairly discombobulated by the world in general. To pass the time, I thumbed through an office copy of some ladies’ magazine, and scanned a photo spread on the Brooks-Bancroft marriage. These two had always seemed to me the oddest of couples. He was a goofy comedian, while she was an elegant and serious actress, who’d won an Oscar for her role as Annie Sullivan in The Miracle Worker. As I was reading, the door opened . . . and in walked a woman who looked exactly like Anne Bancroft. I was stunned: who knew that early pregnancy led to hallucinations?

It turned out, of course, to be the real Anne Bancroft, who was a longtime patient and friend of my doctor. It was titillating, somehow, to be under the care of Mrs. Robinson’s own gynecologist. In later years, when I was researching The Graduate, he discussed her with me briefly, making clear his affection and respect. Then one evening there was a screening at the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences, highlighting Oscar-winning films of 1963. One feature was Mel Brooks’ hilarious short, “The Critic.” Brooks and Bancroft were in the audience, along with Carl and Estelle Reiner. Afterwards, when I grabbed a bite to eat at Kate Mantilini’s (now sadly closed), the two couples were seated in the next booth. I don’t know what they talked about, but Bancroft’s throaty laugh was a joy to hear. Soon afterward, I learned she had died, of uterine cancer, at age 73.

Too bad she didn’t live to have her handprints at Grauman’s Chinese. She might have liked to embed in the concrete, in honor of her most famous role, the outline of a very shapely arched leg.

Published on September 12, 2014 09:30

September 9, 2014

There is Nothing Like a Dame: Remembering Joan Rivers, Elaine Stritch, and Ruby Dee

Seems like most of America’s citizens are busy dumping ice water over their heads. I’m all in favor of supporting ALS research, but (as a resident of a drought state) I wonder if the Ice Bucket Challenge should be re-thought. At any rate, the ladies I salute today—all of whom left us over the summer—would doubtless have preferred to reserve their ice buckets for better things, like chilling magnums of champagne.

These three ladies fall into the category of dames. Not dames in the British sense, mind you. In jolly old England, the word is an honorific reserved for the female equivalent of knights. Many of the British theatre’s brightest stars, like Dame Judith Anderson and Dame Edith Evans, have been granted damehood for their artistic achievements. To us Americans, this may sound rather snooty. True, Dame Judi Dench hardly appears to be the stuck-up sort, but for the imperious Maggie Smith the title seems a perfect fit.

The dames I’m thinking of were All-American feisty broads who rolled with the punches and were never afraid to speak their minds. Like, of course, Joan Rivers. I loved her comedy from her Johnny Carson days, long before she became notorious in some quarters as the Queen of Mean. Yes, her humor had an edge to it, but much of it was directed against herself. In her own eyes, I suspect, she remained forever the ugly duckling, unwed, unloved. That’s the thing about tough dames: they’re usually awfully raw on the inside. That’s why they opt for lots of plastic surgery, or lots of booze.

Take Elaine Stritch, who passed away in July at age 89. I first encountered Stritch as a standout guest on the old Pantomime Quiz ( the celebrity charades show that morphed into Stump the Stars). With her throaty voice and raucous spirit, she was hard to forget. Later I learned she had started out as a Broadway baby, featured in classic musicals like Pal Joey and as Ethel Merman’s understudy in Call Me Madam. She also played dramatic roles, nabbing a Tony nomination as the world-weary small-town waitress in William Inge’s Bus Stop. Though she appeared on TV and in movies, the stage was her real home. In the original Company, Stephen Sondheim wrote for her (and about her) the cynical show-stopper, “Ladies Who Lunch.” It’s a left-handed tribute to those middle-aged gals who, when they get depressed, turn to “a bottle of Scotch/Plus a little jest.”

Stritch knew about both jests and Scotch. I was lucky to see her one-woman show, Elaine Stritch at Liberty, in which she frankly discussed her problems with alcohol, at least some of which connected with her enduring stage fright. Even after decades in the biz, this old trouper—a good Catholic schoolgirl at heart—needed liquid courage before she could face an audience. Toughness on the surface; insecurity inside: that’s what made these dames tick.

I know much less about the personal insecurities of Ruby Dee, pioneering African-American actress and civil rights leader, who died in June. But Dee’s Oscar-nominated performance in American Gangster (at age 83) showed her toughness, as did her refusal, back in 1967, to play a maid in The Incident. The film’s director, Larry Peerce, told me how she demanded that he turn her character into a social worker: “Ruby’s a tough dame. I’ve worked with Ruby a couple of times and I adore her, but she doesn’t take any baloney.”

Another Sondheim tune seems to fit all three dames: “I’m Still Here.” Though they’re gone, I hope they’ll never be forgotten.

This post is dedicated to HBO’s documentary wizard, Sheila Nevins, whose favors to me over the years have included passes to see “Elaine Stritch at Liberty.” Sheila knows all about great dames, because she’s one herself.

Published on September 09, 2014 13:18

September 5, 2014

Everyone’s a Critic: The Demise of Leonard Maltin’s Movie Guide

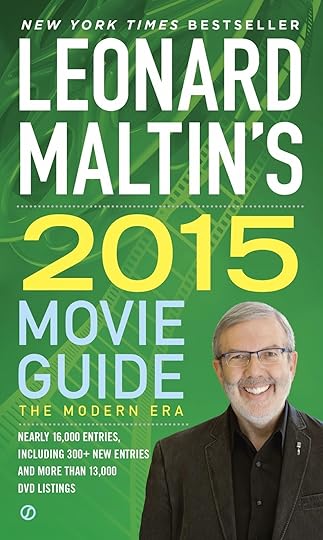

It’s the end of an era. I don’t mean simply the death of Joan Rivers, whose wicked tongue will definitely be missed. But the world has also learned that the 2015 edition of

Leonard Maltin’s Movie Guide

(now just coming onto the market) will be the very last. It’s not that Maltin, like Rivers, has gone to the big red carpet in the sky. Maltin is alive and well, but the movie fans who have been thumbing through his guides since 1969 have become, it seems, an endangered species.

It’s the end of an era. I don’t mean simply the death of Joan Rivers, whose wicked tongue will definitely be missed. But the world has also learned that the 2015 edition of

Leonard Maltin’s Movie Guide

(now just coming onto the market) will be the very last. It’s not that Maltin, like Rivers, has gone to the big red carpet in the sky. Maltin is alive and well, but the movie fans who have been thumbing through his guides since 1969 have become, it seems, an endangered species. As Maltin writes in the preface to his last hurrah: “With ready access to information on the Internet, our readership has diminished at an alarming rate. The book’s loyal followers know that we strive to offer something one can’t easily find online: curated information that is accurate and user-friendly, along with our own reviews and ratings. But when a growing number of people believe that everything should be free, it’s impossible to support a reference book that requires a staff of contributors and editors.”

Don’t waste your tears on Leonard Maltin. The guidebooks have made him a household name, and I expect we’ll continue to see him popping up in movie cameos, on TV (he stars in his own Maltin Minute for DirecTV customers), and in pop culture references. Maltin even gets satirized on The Simpsons, and who could ask for more than that? Whatsaddens me, though, is the way that the era of the professional critic is coming to an end.

Not that I love all critics, by any means. Some are smarmy; some can be bought; some are too self-involved to offer dispassonate opinions. But back when I fell in love with film study, it was exciting indeed to see literate, intelligent men and women slug it out in the pages of my favorite magazines. That was the era when Pauline Kael, publishing in the New Yorker, wrote a 9000-word essay that rescued Bonnie and Clyde from oblivion by detailing its historical antecedents as well as its artistic brilliance. Film criticism in those days was a blood sport. We young intellectuals thrilled to Kael’s passionate defense of a film about 1930s bankrobbers that also managed to offer a critique of our own grim decade. And we were not sorry when venerable Bosley Crowther—he who tsk-tsked primly about violence on our movie screens—was suddenly replaced, after twenty-seven years at the New York Times, by a feisty young woman. (Yes, Crowther in his day had been courageous, championing foreign art films and strongly opposing censorship at the height of the McCarthy era. But his time had, in our not-so-humble opinions, definitely come and gone.)

As Pauline Kael gained stature, along with a permanent sinecure at the New Yorker, there developed a battle royal between her followers and those of Andrew Sarris, who published chiefly in the Village Voice. Kael was a pop culture fanatic, who through the power of her prose could make a wan re-make of King Kong seem worth watching. Sarris, on the other hand, was America’s pre-eminent supporter of Europe’s auteur approach to film criticism. What fun to compare their outlooks! And I still have on my shelf a rapidly-eroding copy of Film 67/68, a lively publication from the National Society of Film Critics in which America’s sharpest reviewers went head to head, gleefully praising their favorite films and condemning the many Hollywood offerings they considered unworthy.

Anyone can be merely snarky, as the Internet proves on a daily basis. But, yes, I miss the cogent, educated arguments that make true critics worth reading.

Published on September 05, 2014 10:50

September 1, 2014

Who Ya Gonna Call?: A Labor Day Salute to Saul Saladow

Everybody knows George Clooney. And nearly everyone recognizes the name and face of Steven Spielberg. But Hollywood is also full of worker bees who get little glory. They’re not in it for the golden statuettes or fat paychecks, but rather for the excitement of making movies. On Labor Day, I salute them.

Actor Van Heflin once said, “If you really love the business, you can find a way to survive in it. You may not be an actor, but you can do something.” That’s exactly what happened with Saul Saladow. Saul, a buddy of mine at L.A.’s Hamilton High School, found a home in the school’s drama department. He later earned a theatre degree at Cal State Northridge, but it was clear he wasn’t cut out to be an actor. (As a one-time scene partner of Saul’s, I can vouch for that!) Post-graduation, he got a gig at Warner Bros. as a bicycle delivery boy. One day there was an opening in the editorial department for someone able to file trims: claiming more experience than he actually had, he went to work, learning film editing on the job.

Saul’s talent for organizing stood him in good stead, as did his firm dedication to his craft. Eventually he was hired by producer-director Ivan Reitman, with whom – over a period of three decades -- he made such films as Ghostbusters, which is now enjoying its 30th anniversary re-release. While in production he often worked fourteen-hour days, sometimes seven days a week. He’s also had the odd experience of flying films to New York, in order to screen them for individual big-name critics. Studio brass demanded that the precious film canisters to be accompanied at all times. So they’d pay for two first-class seats: one for Saul, one for the movie. (No, he didn’t have to lug it into the aircraft’s lavatory when nature called.)

Though his job left little time for an active social life, Saul wasn’t about to complain: “I was very well paid, and I loved what I was doing.” Why did he never rise above the ranks of assistant editor? He feels he simply lacked the drive and the self-confidence to interact with directors, who often turn into General Patton in the editing room. If you’re the top editor on a big project, you can’t allow yourself to be intimidated. Furthermore, Saul notes that as someone who’s “not very musical” (I can vouch for that too!), he would have found it hard to work on editing a film’s musical score.

At about age sixty, Saul retired with a comfortable pension. His very last project was Reitman’s My Super Ex-Girlfriend (2006). He would like to have stayed for five or six more years, but the industry was changing so rapidly that it seemed time to leave. The directors for whom he had worked (including Sydney Pollack as well as Reitman) were starting to slow down. And this was the era of the changeover from linear to digital editing: the transition would have required of him massive retraining and a whole new way of thinking about film.

Now that he’s retired, Saul can make time for his many friends. But he’s also managed to hold onto his love of drama. He’s a dedicated play-goer, and for decades he’s been active with a community group in Santa Monica, the Morgan-Wixson Theatre. Though he’s long since stopped trying to be an actor, Saul now produces individual shows and serves on the board as executive vice-president. When I caught his recent production of Avenue Q, he was happily taking tickets and selling candy. Yes, he’s home.

Published on September 01, 2014 09:53

August 29, 2014

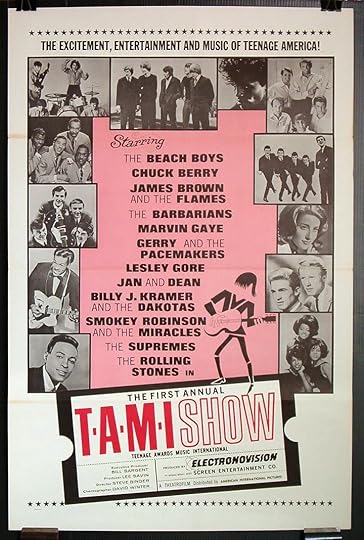

James Brown Gets On Down at the T.A.M.I. Show

Too bad that the new James Brown biopic, Get On Up, is apparently something of a dud. I’ve heard praise for the performance of Chadwick Bosemen (who was brilliant as Jackie Robinson in 42), and the film is produced by an interesting pair of heavyweights, Imagine’s Brian Grazer and his Satanic Majesty himself, Mick Jagger. But critics and audiences are giving decidedly mixed reviews to the film’s scrambled chronology and the directing chops of Tate Taylor (The Help).

My own interest in James Brown stems from a film I saw in a UCLA class devoted to the movie musical. I was there to soak up the pleasures of Fred Astaire, Gene Kelly, and MGM’s technicolor extravaganzas. So I was nonplussed when I discovered we’d be watching something called The T.A.M.I. Show. Say what? This oddly named concert film captures, in unimpressive black-and-white, an event staged in October 1964, right here in Santa Monica. The T.A.M.I. Show (whose name stands for “Teen Age Music International) was a live concert at the Santa Monica Civic Auditorium that was videotaped by a secretive process called “Electronovision” and then transferred to film for theatrical release.

The film version of The T.A.M.I. Show was distributed by American International Pictures, well-known for flicks with youth appeal. So you can imagine the thinking that went into this project. It was clear in 1964 that young people were developing their own subculture, and had the buying power to support it. So the folks behind the show were trying to tap into the kind of musical acts that attracted the young. They gathered a remarkable collection of stars-on-the-rise, mixing soul music (Marvin Gaye), surf music (The Beach Boys), Motown (The Supremes), British Invasion (Gerry and the Pacemakers), and teen angst ballads (Leslie Gore, of “It’s My Party and I’ll Cry if I Want To” fame). Local legends Jan and Dean were the hosts, zipping into the barnlike auditorium on skateboards. The Civic’s seats were packed with screaming teenagers who were too busy bouncing up and down to actually listen to much of the music. Their energy was matched by the gaggle of go-go dancers who twitched, shimmied, fruged, and watusied non-stop throughout the show. (One, I’m told, was a young Teri Garr.)

Though the final act featured a very youthful Mick Jagger and the Rolling Stones, who were then new to U.S. audiences, there’s no doubt in anyone’s mind that the real star of The T.A.M.I. Show was James Brown. The fabulously pompadoured Brown, nattily attired in a checked jacket and matching vest over a black shirt, strutted onto the stage and belted out four numbers, each more outrageous than the last. He crooned; he cried; he led the audience in a spirited call-and-reponse; he glided through quirky dance steps with an ease that suggests he was a key inspiration for Michael Jackson’s moonwalk. Sometimes he was so overcome with the emotion of a song that he dropped to his knees, at which point a backup singer would rush to pat him on the back and drape a regal-looking cape (yes, a cape!) over his shaking shoulders. I’ve never seen anything like it. Nor, apparently, had the mostly middle-class white kids in the audience. Future filmmaker John Landis (The Blues Brothers) was in the crowd as an eighth-grader. When Mick Jaggers followed Brown’s performance, his immediate reaction was “Who is this English twerp? Bring James Brown back on the stage!)

Jagger himself has apparently rued his group’s star billling over Brown, whom he had long idolized. In helping produce Get On Up, he was simply trying to make amends.

Published on August 29, 2014 08:58

August 26, 2014

Jonathan Gording, OD: Eyes on the Prize

So Guardians of the Galaxy is once again at the top of the domestic box office. I’m someone who generally prefers artier films (like the dark but fascinating Calvary). But every once in a while I need my popcorn-movie fix, and Guardians certainly provides that. For one thing, it’s a visual treat: this is a galaxy in which nearly everyone has a spectacularly off-kilter look. In one of the earliest scenes, when Djimon Hounsou opened wide his powder-blue eyes, I couldn’t help thinking about my optometrist, Dr. Jonathan Gording.

No, Dr. Gording didn’t work on Guardians of the Galaxy. But he has an award-winning sideline crafting contact lenses for Hollywood. The walls of his office are full of posters from big-name movies like 127 Hours (for James Franco he made lenses that simulated pink eye) and The Curious Case of Benjamin Button. He’s something of a Tom Cruise specialist, having worked on Interview with the Vampire, Vanilla Sky, and Minority Report. For 2011’s Mission Impossible: Ghost Protocol he joined with an SFX team to concoct a video camera embedded in a contact lens and supposedly activated by blinking. But his real expertise is in the realm of the supernatural. He’s the go-to guy for zombie and vampire eyes, on such shows as The X-Files and True Blood. Southern California is a land where delis and drycleaners decorate their walls with autographed headshots of their celebrity clientele. But Jonathan Gording, OD, has on his wall a wooden stake, a souvenir of the 100th episode of Buffy the Vampire Slayer.

Naturally, for Hollywood creative types, it’s all about the look of Dr. Gording’s lenses. But as a optical professional, he puts much effort into ensuring cast members’ comfort and eye health. When I mentioned a well-known star who had a terrible time adapting to the full-eyeball yellow lenses required for one fantasy production, Gording made clear that if he’dbeen charge, the lenses might have caused far less problem. But he also emphasized that this particular star – who’d been fitted by Gording on his breakout film – was a chronic complainer, rarely satisfied with any aspect of his costumes and makeup.

Working with Hollywood folk, it seems, is a big challenge, for reasons that have nothing to do with the medical. Just recently Gording had to help an award-winning but now elderly actress turn into a zombie. When he showed up, she was already notorious on-set for stripping off her top to reveal what he delicate calls “her womanly wiles.” When he went to do measurements on her eyes for “zombie lenses,” she announced she was a 36 and threatened to prove it. The skewed priorities of showbiz types also give him pause. He remembers getting a Monday morning call from an assistant director, “Dave,” who had signs of a detached retina. In this critical situation, Gording urged Dave to come to his office immediately. Then Dave started stalling, citing a heavy workload. Eventually he accepted a Wednesday appointment. On Tuesday, though, he was carted off to the emergency room.

When Gording decided to pursue a Hollywood career, other optometrists in the biz gave him the cold shoulder. But he enjoyed a warm welcome from the late Dick Smith, whose prosthetic work on such films as The Godfather and The Exorcist revolutionized the field of movie makeup. The gentlemanly Smith told him he’d have a ball. Which, of course, has been quite true. Leaving his office one day, Gording cheerily told me, “I’ve got to go torture someone.” Yes – someone needed his eyes propped open on CSI.

For those who appreciate things that go bump in the night, I’ll be speaking on Roger Corman’s screen adaptation of Edgar Allan Poe’s The Masque of the Red Death at the Weird Weekend (featuring screenings, a storytelling competition, and other fun) sponsored by the Historical Society of the Upper Mojave Desert. The dates are September 12-13 and the place is Ridgecrest, California. More info awaits at 760-375-8456.

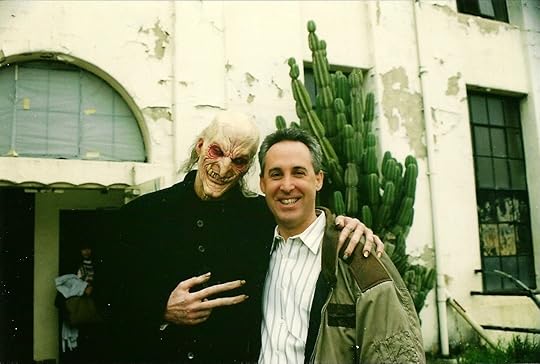

Dr. Gording (he's on the right) and friend from Buffy

Dr. Gording (he's on the right) and friend from Buffy

Published on August 26, 2014 12:06

August 22, 2014

Covering Syria: From Page to Screen

When my colleague Howard Kaplan first published The Damascus Cover back in 1977, I imagine he gave some thought to his book’s movie potential. After all, he’d written a fast-paced spy novel full of intrigue, betrayals, and narrative twists galore, set amid Syria’s bloody byways. I doubt, though, it ever occurred to him that Hollywood would come calling in 2014.

When my colleague Howard Kaplan first published The Damascus Cover back in 1977, I imagine he gave some thought to his book’s movie potential. After all, he’d written a fast-paced spy novel full of intrigue, betrayals, and narrative twists galore, set amid Syria’s bloody byways. I doubt, though, it ever occurred to him that Hollywood would come calling in 2014.Well, not Hollywood exactly. There’s British money involved in this modest indie production, now called simply Damascus Cover, which is slated to begin shooting in Morocco this fall, with James D’Arcy and Abigail Spencer in major roles. But writer-director Daniel Berk (who once helped connect John Travolta with Quentin Tarantino, and has also served as the Senior Envoy for Cultural Affairs at the Israeli Consulate in Los Angeles), shares Howard’s fascination with the Middle East. Berk enlisted a second screenwriter, Samantha Newton, to deepen the film’s central romantic relationship and otherwise up the dramatic stakes. Some of Howard’s own story suggestions were taken, but he’s the rare novelist who seems delighted by the changes that have been made to his original work. With both Syria and Israel all too prominent in the news of late, it seems high time to make a film that follows an Israeli spy who’s gone undercover in Damascus, masquerading as an ex-Nazi businessman while striving to carry out a dangerous mission.

A Nazi enclave in Syria decades after the close of World War II? That’s the kind of historic detail on which Howard Kaplan thrives. He’s a student of Middle Eastern history, one who spent several years living in Israel, speaks fluent Hebrew, and has contacts of all persuasions in the region about which he writes. During his student years, he made a brief, clandestine visit to Damascus, then enhanced his knowledge of this teeming, fascinating city by studying detailed maps as well as every memoir and travel book he could find. As he puts it, “God bless the Brits, who go everywhere and write about it.”

Howard’s enthusiasm for cloak-and-danger stories was primed in the early 1970s when he made two trips to the Soviet Union. On the first, he successfully smuggled out a dissident's manuscript on microfilm. The second time around, he was arrested and interrogated for several days by Soviet police before being expelled from the country. (This incident contributed to the plot of his second published novel, The Chopin Express.) To flesh out The Damascus Cover, he read widely about the Israeli spy Eli Cohen who, explains Howard, “had been highly placed inside Syrian Intelligence before the Six Day War and provided Israel with much of the intelligence to allow them to take the Golan Heights from Syria in that war. He was uncovered and hung publicly in Marjeh Square in Damascus.” In addition, Howard steeped himself in the writings of Somerset Maugham, Eric Ambler, Graham Greene, and especially John Le Carré, whose espionage novels benefit from his real-life experiences in British Foreign Intelligence. He’s also been inspired by Ken Follett, who early in his career wrote a vivid novel about Afghanistan without once having set foot in that troubled land.

Howard prides himself on his even-handedness, which comes from decades of researching both Israeli and Arab points of view. His objectivity on thorny Middle Eastern matters has been noted by many reviewers. He also knows how to spin a good yarn. Bestselling author Clive Cussler is a fan, saying, “Kaplan is up there with the best.” Let’s hope the movie version of The Damascus Cover lives up to expectations, and sheds light on what’s happening in the Syria of today.

The movie poster, as of now

The movie poster, as of now

Published on August 22, 2014 11:03

August 19, 2014

Of Poor Doors and Balconies

As racial and social tensions mount in Ferguson, Missouri, I’m also struck by a new phenomenon that’s perhaps unique to the two coasts: the “Poor Door.” It seems that some pricey residential towers in Manhattan and at least one luxury property in West Hollywood have been trying to do a bit of fancy footwork around local zoning ordinances. Developers are often given certain valuable concessions when they promise to offer a fixed number of affordable “below-market-rate” apartments along with costlier units in the same building. In order to separate the haves from the have-nots, their new dodge is to create entrances that are separate but hardly equal.

Apparently, this sort of thing is a matter of course in London, where class snobbery is nothing new. But a construction project in New York that routes the occupants of the cheap flats to a much more modest door around the corner from the building’s posh entry hall has understandably raised a hue and cry. I was surprised to learn that something similar was recently proposed in West Hollywood, a SoCal city that has long been dedicated to gay rights and the protection of renters. When WeHo housing officials learned that the developers planned to build separate entrances, and also to bar low-income folk from their new project’s pool and spa, they cried foul. Quickly backpedaling, the project’s backers solemnly promised that their building’s amenities (including its main entrance) would be open to all.

In following the controversy, I can’t help thinking about segregation, and its impact on our nation’s movie houses. Veteran TV and movie producer Romell Foster-Owens grew up in San Diego, as part of a large, close-knit African-American family. The weekly ritual for Romell and her siblings was to spend Saturdays at the movies, munching on snacks from the concession stand and generally hanging out. Then, when she was a boisterous eleven-year-old, the family drove cross-country to visit relatives in the Deep South. It was in Warner Robbins, Georgia, a sleepy town near a large military base, that she learned about life’s realities. She was so excited about seeing Flipper at the local cinema that her parents let her run in ahead of them. As she recalled to me: “I’m in the lobby and I’m wanting to buy popcorn. And the lady’s telling me, in this very strange accent to me, that I had to go around the back. And I didn’t understand what she was saying, and I’m still being persistent: ‘I would like to get some popcorn and a drink.’ And she’s saying, ‘Nope. Can’t help you. You have to go around the back.’”

Her parents quickly yanked her aside and explained that she’d have to enter through a side door and climb to a “Colored Only” balcony. Half-way up the stairs there was a niche where she could purchase refreshments. They tried hard to make her balcony seat seem like a cool adventure. Nonetheless “I’m still upset, because I’m sitting up in the balcony, and that’s not where I want to be. And that was probably one of the first times I felt like second-class citizenship.”

Romell Foster-Owens will always remember Flipper, not for the antics of the friendly dolphin, but because of the anger that consumed her that day: "After all I had the same money and had to pay the same price for my ticket as anyone else." But Warner Robbins was hardly unique: virtually all Southern cities relegated blacks to the rafters, and I suspect some Northern ones did too. (Anyone have any detailed info on that?) And it wasn’t just movie theatres. Check out this courtroom scene near the end of To Kill a Mockingbird.

Published on August 19, 2014 09:03

August 15, 2014

Back-to-School: Sir Dares You to Go Up the Down Staircase

For me it’s shorts-and-sandals weather, so it’s hard to imagine young people going back to school. I’m sure that most adolescents would much rather head for the movies. But of course movies about unruly students—and the teachers who try to tame them

—are a genre unto themselves. The year 1967 featured two: Up the Down Staircase and To Sir, With Love.

The former, a gritty low-budget black-and-white feature, somewhat parallels To Sir, With Love, with Sandy Dennis assuming the Sidney Poitier role as a brand-new teacher who walks into a tough situation. Adapted from a best-selling novel by the late Bel Kaufman, it understands that a public school is a bureaucracy run amok. Shot in an actual New York City high school and incorporating non-professionals into its cast, it is one of the most convincing movies ever made about secondary education. Within its student body, some are hopeless and a few are dangerous, but others remain capable of making progress. The film does an honest job of showing both the risks and the rewards of being a classroom educator.

Up the Down Staircase earned only a third as much money as To Sir, With Love. The obvious explanation is that Sandy Dennis is no Sidney Poitier. Yes, Dennis was much admired for this performance, even winning the Best Actress prize at the 1967 Moscow Film Festival. (Rumor has it the film was submitted by the U.S. Department of State to counter Soviet propaganda that all American schools are racially segregated.) Yet Dennis’s spirited but vulnerable Sylvia Barrett is no match for Poitier’s suave, charismatic Mark Thackeray. The marketing campaigns for the two films tell the tale. In one prominent ad, a well-dressed Poitier is shown standing behind his desk, his hands splayed out flat on its wooden surface. He’s leaning forward, and his face is grim. Clearly, he’s a man who means business. This fact is reinforced by the words scrawled on the blackboard behind him: “You’ve got to make them cool it and call you ‘Sir’!” What To Sir, With Love is promising is a powerful hero, one who scores an almost-military victory (note the emphasis on the word “Sir”) over the young roughnecks who threaten to bring him down. Audiences were clearly pleased: the film was a major hit.

Many newspaper ads for Up the Down Staircase contained a full-length image of Dennis, carrying books and a large tote bag; she looks slightly disheveled, and also wary of the leers she’s getting from the teens loitering in her path. Other ads featured a male hand, complete with snake tattoo, writing boldly on the chalkboard, “DEAR TEACH—THE THING I LIKE BEST ABOUT YOU IS YOUR LEGS.” Above this implicitly sexual taunt, there’s a glimpse of Dennis’s anxious face. Though much of the marketing for Up the Down Staircase contains in small print a line clearly intended to be inspirational—“The year’s #1 best-seller picks you up and never lets you down”—all visuals emphasize the leading character’s feminine fragility. Poitier represents the teacher as victor, as someone who, despite his air of refinement, is tough enough to tame classroom hoodlums. Dennis, by contrast, is the teacher as potential victim. Nonetheless, the fact that a movie is devoted to a female whose dilemma is professional rather than romantic, and whose concern for her students’ progress is not to be confused with maternal softness, shows a rare and welcome respect for the idea of a woman finding her place in the world of work.

Here’s to teachers – and their students – everywhere!

Published on August 15, 2014 12:25

August 12, 2014

Robin Williams: Good Night, Clown Prince

The death of Robin Williams hit me between the eyes. He was just such an integral part of my young-adult years. I’ll always think of him as Mork from the planet Ork, looking at life on earth from a perspective both uniquely askew and consistently funny. (I’m sure I have those rainbow-striped suspenders around somewhere.)

Williams had many talents. But even he couldn’t do the impossible, like save a picture whose script is faulty. This lesson was brought home to me when my husband insisted we see 1990’s Cadillac Man. Sure, the reviews weren’t great, but with Robin Williams as star, how bad could it be? After surviving 97 minutes of lame attempts at zany humor, I learned a lesson I still share with my screenwriting students: without a strong script, even the best-cast film cannot fly.

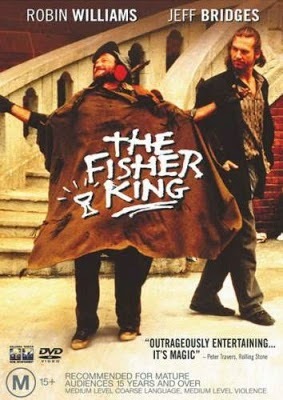

Fortunately, most of Robin Williams’ projects were considerably better. My favorite period of his work ran from 1980 into the early 1990s, when he was blending offbeat humor with a satiric edge that managed to make a serious social comment. I remember Moscow on the Hudson (1984) and Good Morning Vietnam (1987) as both trenchant and hilarious. And his portrayal of a deranged homeless man in 1991’s The Fisher King (opposite the equally brilliant Jeff Bridges) is one I’ll long cherish. I can’t point to deep social meaning in his manic vocal performance as the genie in Aladdin (1992). But of all the Disney musicals this is the one that had me (along with my kids) singing and dancing outside Hollywood’s El Capitan Theatre, so delighted were we with the sheer antic exuberance of it all.

I admired the touching Dead Poets Society (1989), with its belief in the written word as well as the nobility of the teaching profession, though its “seize the day” message was undeniably heavy-handed. And this film seemed to send Williams in a direction I didn’t much appreciate: toward movies that reeked of sentimentality. I’m perhaps alone in the world in disliking 1997’s Good Will Hunting. (I do, though, admire the smarts of screenwriters Matt Damon and Ben Affleck for adding to their screenplay what they originally called the Harvey Keitel part. Here’s how film historian Peter Biskind describes it: “They tailored the part of the therapist to a Hollywood star, any star, gave him the best lines, made it small so he could fit it into his schedule.” The role would have worked for Morgan Freeman or Meryl Streep, but ultimately Williams was cast as the bereaved but still funny therapist, and won an Oscar.) The next year, he starred in an even more egregiously schmaltzy film, Patch Adams, about a doctor who plays the clown to cheer up his dying patients. I had the misfortune of seeing it (over and over) in a hospital waiting room while a family member’s surgical procedure dragged on.

Three decades ago, I was writing a magazine story about a Hollywood branch of the famous Paul Sills improv troupe, which included such lively second bananas as Avery Schreiber, Hamilton Camp, Richard Libertini, and Dick Schaal. For these talented eccentrics, the challenge was finding a way to work together, spontaneously spinning a story out of the wispiest of materials. At one performance, the newly famous Robin Williams was announced as a special guest. Of course he proved remarkably quick and inventive. But he was not a team player, instinctively pulling focus from those who shared his spotlight. It was his destiny, I guess, to go it alone. Perhaps the price of being Robin Williams was just too high to bear.

Published on August 12, 2014 09:17

Beverly in Movieland

I write twice weekly, covering topics relating to movies, moviemaking, and growing up Hollywood-adjacent. I believe that movies can change lives, and I'm always happy to hear from readers who'd like t

I write twice weekly, covering topics relating to movies, moviemaking, and growing up Hollywood-adjacent. I believe that movies can change lives, and I'm always happy to hear from readers who'd like to discuss that point.

...more

- Beverly Gray's profile

- 10 followers