Beverly Gray's Blog: Beverly in Movieland, page 115

November 18, 2014

Brad Krevoy: Dumb (and Dumber) like a Fox

Who woulda thunk it? Releasing a sequel to Dumb and Dumber, twenty years later, has turned out to be a smart move. Dumb and Dumber To, reteaming original stars Jim Carrey and Jeff Daniels, pulled in $38 million in its opening weekend, leading all films at the box office.

The 1994 Dumb and Dumber launched the careers of the Farrelly brothers. It further confirmed that Jim Carrey – also featured that year in Ace Ventura: Pet Detective and The Mask -- was a genuine comedic star. Carrey and the Farrellys have gone on to be household names, especially in households that appreciate outrageous goofiness. Far less well known are the film’s producers. But one of them is a former colleague of mine, and it’s a pleasure to salute him here.

Brad Krevoy graduated from Beverly Hills High School, then went on to study at Stanford. After passing the bar, he entered the field of entertainment law. Then, in a 1983 episode that could have been concocted by a Hollywood screenwriter, Brad attended a Stanford football game. Also in the stands that day was low-budget filmmaker Roger Corman, himself a Stanford grad. Brad had just read an article about the coming of the VCR, and how this new technology could revolutionize the film industry. He mused to Roger that the big studios would doubtless be slow to take advantage of the home viewing audience, preferring to wait until the market matured. Roger, he felt, was well equipped to ride the coming wave by quickly supplying product to fill up video store shelves. As Brad told me, “I said that to Roger on a Saturday, and Monday I was working for him. ”

Brad’s role initially was to handle Concorde’s business affairs, looking for new opportunities as well as new sources of movie funding. His hunch about video quickly paid off: “As the video business grew, we were at one point the largest supplier. We had deals with every major video distribution company in the world, to the point where we had orders in excess sometimes of 30 to 40 films a year we had to produce, because we had all these orders. It was a really extraordinary period.” (I personally remember those busy days quite well. Yes, it was extraordinary!) Though Roger sent him out on occasion to slap competitors with lawsuits, Brad had no delusions about his prowess as a litigator. But moviemaking quickly got into his blood, and the lessons he learned from the master have stayed with him ever since.

As he moved into his own producing career, as founder and CEO of the Motion Picture Corporation of America, Brad always kept in mind the Corman mantras. Such as: rather than follow a trend, it’s wise to try satisfying the needs of specialty audiences. Says Brad, “Any film that I’ve ever had that’s done big business, it was because I was trying to play the niches.” He cites Dumb and Dumber as such a broad, silly comedy that no established studio would dare to make it. Roger taught him that “you really don’t have to be the biggest or the best on the block. Do the best you can . . . if you’re going to do a smaller film, be the best at the smaller film, and compete at your own level, that you’re comfortable with.”

Brad Krevoy is now the producer of over one hundred films, including the Emmy-nominated Iraq War teledrama, Taking Chance and the upcoming holiday romance, A Royal Christmas. All hail to yet another Cormanite who didn’t take dumb for an answer.

Published on November 18, 2014 12:57

November 14, 2014

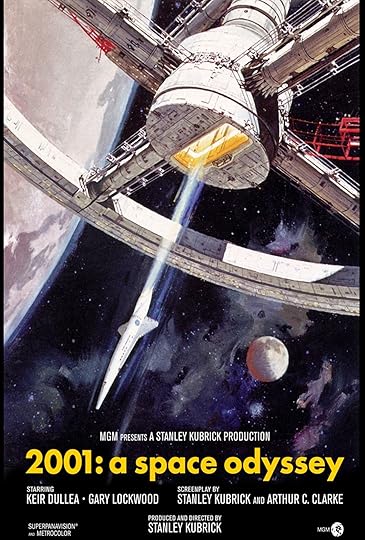

"2001": The Grand-Daddy of All Interstellar Movies

Last year it was Gravity; this year it’s Interstellar. In the real world of space exploration, the focus is now on robotics, like the European Space Agency’s Rosetta mission that this week (semi-)successfully landed an unmanned spacecraft on a comet. But moviegoers still enjoy watching men and women personally contend with the perils of outer space. Space-travel movies date all the way back to the 1902 Georges Méliès fantasy, A Trip to the Moon. In the era of Sputnik, Roger Corman got into the act with 1958’s hilariously low-budget War of the Satellites. Of course there’ve been outer-space films aplenty. But the one that made all the difference was released in 1968. It was, of course, Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey.

When 2001 first appeared, Time Magazine hailed it as “the most dazzling visual happening in the history of the motion picture.” Today, when asked where he’s spotted the long-range impact of Kubrick’s space adventure, film industry veteran Bruce Logan responds, “Well, everywhere. From on-screen graphics for TV stations on down.” Bruce should know. A London-born cinematographer and effects specialist, he’s worked on such classic fantasies as Star Wars, TRON, and Batman Forever. But he started out as a self-taught animator, one who began his motion picture career at Britain’s MGM Elstree studios as part of the special photographic effects unit on 2001, under the supervision of the great Douglas Trumbull. Says Bruce, “2001 was my film school.” For the first year of his involvement, he contributed to the animation of what looked like a spacecraft’s computer screens. Given that the film was made years before such computers existed, these computers today look remarkably convincing. He’s particularly proud of his work on the read-out monitoring the “sleeping” astronauts who all flat-line, in one of the film’s most disturbing moments. It took a while, though, before he was able to fully appreciate Kubrick’s achievement: “For the first ten or twenty years after the movie came out, to me it was just a bunch of shots that I had worked on, strung together. . . . I think that the time that I saw the genius most was when I saw it about a year ago, at the Academy, without any recollection – and I was able to see for the first time what a brilliant piece of work it was.”In preparation for filming 2001, Kubrick had his visual effects team watch such sci-fi flicks as Forbidden Planet and Fantastic Voyage (which Bruce now calls “that terrible movie with bad special effects where they go inside the body”). Ultimately, though, Kubrick’s vision was wholly unique. It’s worth remembering that when the film was being planned, NASA missions were paving the way for the 1969 moon landing of Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin.While Kubrick and company were deciding what the moon in their film should look like, actual photographs of the far side of the moon were starting to be made available for the first time. The filmmakers seriously considered altering their visual concept to make it resemble the lunar surface as seen in NASA’s photographs, but then admitted to themselves that “the moon looks kind of boring.” That being so, they decided to forget about authenticity and stick with their original design plan. . Though Bruce made a Roger Corman detour upon first coming to America, he’s best known for his work on big-budget Hollywood spectaculars: “I blew up the Death Star. It wasn’t Luke, it was me! That’s one of my claims to fame.”

Published on November 14, 2014 11:16

November 11, 2014

Saving Charlie MoPic

War movies continue to attract audiences, as the strong box office for Fury makes clear. On Veterans Day 2014, I want to remember the war that tore my own generation to shreds: Vietnam. Though Hollywood’s first response to the Vietnam conflict was John Wayne’s flag-waving 1968 flick, The Green Berets, the following decades brought cinematic reassessments of America’s role via The Deer Hunter (1978), Apocalypse Now (1979), and Platoon (1986) Those films all featured major stars and won prestigious awards, including multiple Oscars. But today I’d like to salute an indie, 84 Charlie MoPic. Shot on a shoestring in Southern California, it has been hailed by Nam veterans as a truly realistic depiction of a grunt’s life.

Made under the auspices of the Sundance Institute, 84 Charlie MoPic cleverly finesses its low budget by pretending to be documentary footage shot by a young recruit from the U.S. Army’s motion picture unit. His subject is a reconnaissance patrol operating behind enemy lines. As he conducts in-the-field interviews with five tight-knit platoon members as well as the eager new lieutenant who sees war as an opportunity for his own advancement, we get an increasingly graphic view of the stresses and strains of combat. The cameraman, known in military parlance as MoPic, at one point hints at his own role in this subjective-camera saga: “I was working in a lab, back in the rear -- post-production. Sometimes we would get these cans of film in, you know? No cameraman, just the reels of film. And, we hear he got shot, he's dead or something. But the spookiest thing is waiting for that film to develop, man, because you didn't know what you were gonna see. Sometimes you saw nothing. But other times . . . “

A fan on the IMDB site gives credit for 84 Charlie MoPic’s authenticity to the film’s two technical advisors, Russ Thurman and Dale Dye, both of whom served in the Marine Corps. As he explains, “Dye's method of running the actors through a mini-boot camp helps raise this film to the level of Platoon and Saving Private Ryan, his more widely-known achievements.” But it’s hardly fair to forget the film’s writer-director, Patrick Sheane Duncan, whom I had the privilege of interviewing once upon a time.

Pat, like so many in Hollywood, was a Roger Corman alumnus. He started out as an accountant, though one who aspired to write. Vietnam was his first big subject. Too poor to go to college, he’d enlisted in the Army in 1965. For fifteen months from 1968 through 1969 he served in the 173rdAirborne Brigade. Once he returned home, he was determined to tell the truth about his combat experience, which was a far cry from the sentimental pap he saw on movie screens. Pat pointed out to me that Charlie MoPic and his later Vietnam films were distinct because “they weren’t about the war. They were about the soldiers. I tried to make them more intimate.” He well remembers that “when we showed MoPic at Sundance, some kid came up to me . . . and he says, ‘I didn’t realize it but sometimes when people die, they don’t get any last words.’ That’s because in all those war movies we saw, the guy layin’ there had a nice speech about ‘Tell my mom. . . .’”

For a filmmaker with such a powerful perspective on men at war, Pat Duncan’s public reputation rests on something quite different. In 1995 he wrote a quiet little film that paid tribute to a dedicated music teacher. Nobody dies in Mr. Holland’s Opus.

Published on November 11, 2014 09:38

November 9, 2014

Casting a Ballot in Movieland

Cindy Crawford phoned me last evening. Yes, I’m talking about Cindy Crawford the supermodel. But I can’t pretend that she and I are close chums. She was phoning to tell me that she has kids in my local school district (who knew?), and that I should think about voting for the school board candidate of her choice. Personally, I have little interest in Cindy’s preferred school board member. The Santa Monica-Malibu Unified School District serves my city and also the much tonier enclave up the coast. I’m not much inclined to give Cindy and her beachfront neighbors their own handpicked representative.

Cindy Crawford phoned me last evening. Yes, I’m talking about Cindy Crawford the supermodel. But I can’t pretend that she and I are close chums. She was phoning to tell me that she has kids in my local school district (who knew?), and that I should think about voting for the school board candidate of her choice. Personally, I have little interest in Cindy’s preferred school board member. The Santa Monica-Malibu Unified School District serves my city and also the much tonier enclave up the coast. I’m not much inclined to give Cindy and her beachfront neighbors their own handpicked representative.All across the country, elections bring out superstars, whether political stars like Bill Clinton or showbiz celebrities. Pop music icon Carole King, for one, has shown up in my email in-box, urging me to donate on behalf of several candidates for the U.S. Senate. Here in California, singer-songwriter John Legend is stumping for Marshall Tuck, who hopes to be the next State Superintendent of Public Instruction. And such movieland insiders as Matt Damon and Norman Lear are backing with serious bucks a candidate for State Assembly with the unlikely name of Prophet Walker. Walker, who hopes to represent a blue-collar district encompassing Compton and Watts, has a life story seemingly made for Hollywood. The son of a birth mother who succumbed to heroin addiction when he was still an infant, he grew up in South Central L.A. At sixteen, he was convicted of armed robbery, then sentenced to six years in prison. It was while behind bars that he began an unlikely turnaround that led him to graduate from college and embark on a career as a community activist. If he wins his race, his story will have a true Hollywood ending.

But Hollywood is more than superstars and the intriguing underdogs whose up-from-the-gutter stories would make for a great movie-of-the-week. There are also those unionized behind-the-scenes crew members who are worried that their jobs are being outsourced to New York, New Mexico, and Canada. My good friend Ben Allen, an outstanding candidate for State Senate, has circulated a mailer that trumpets his endorsement by all Los Angeles-area locals of IATSE, the international union representing film and TV production folk. He’s also won the support of Councilman Paul Krekorian, author of the first California bill to establish an entertainment tax credit for the Golden State.

Similarly, one would-be L.A. County Supervisor, Bobby Shriver, has sent out flyers emblazoned with a vintage photo of a movie premiere on Hollywood Boulevard. The text reads: “We Founded the Movie Industry. Let’s Bring Our Jobs Back.” He also lets it be known that among his staunch supporters is Steven Spielberg, along with several Kennedys. Shriver’s opponent, Sheila Kuehl, likes to play up her own Hollywood connection. Back in the day (before law school and years of service in the California State Senate) she was Sheila James, who memorably played plucky little Zelda Gilroy on The Many Loves of Dobie Gillis.

Over the years, Hollywood has had its own fun with movies about politics. Among the best, of course, is Frank Capra’s Mr. Smith Goes to Washington, in which idealism triumphs over the schemes of corrupt politicians. Much more cynical is Preston Sturges’ The Great McGinty. I loved Alexander Payne’s wicked high school satire, Election, in which a campaign for student body president ends up laying bare what can happen when a candidate who will stop at nothing (Reese Witherspoon) takes on her high-minded civics teacher (Matthew Broderick).

As for Election Day 2014, may the best man (or woman) win. Go Ben!

Published on November 09, 2014 07:57

November 7, 2014

Cicely Tyson’s Bountiful Trip

Old age is definitely not a picnic. An elderly lady of my acquaintance once uncharacteristically used an expletive to express how she felt about the so-called Golden Years. If you happen to be an actress, even a distinguished one, becoming an octogenarian is not a great career move . . . unless you’re Judi Dench or Betty White.

For actors it’s slightly easier. Every few years Hollywood offers up a terrific codger role for a greying patriarch type like Art Carney (an Oscar winner for 1974’s Harry and Tonto). More recently, such iconic actors as Clint Eastwood (Gran Torino), Jack Nicholson (About Schmidt), Bruce Dern (Nebraska), and Bill Murray (St. Vincent) have played with distinction elderly men in crisis, often upping their actual age to portray characters much older than themselves.

But strong old-lady roles are few and far between. Which is why Joan Crawford and Bette Davis once found themselves playing grotesques in Whatever Happened to Baby Jane? Happily, Davis rounded out her long career with a respectful role in 1987’s The Whales of August, opposite one of Hollywood’s immortals, the great Lillian Gish.

Gish, of course, got her start in silent films. By the time she starred in D.W. Griffith ‘s Birth of a Nation in 1915, she had appeared in almost fifty screen projects. Though Gish’s image was that of fragile femininity, there’s no question she could be tough. Unlike most of her peers, she survived the transition to talkies, giving one of her most powerful performances as a valiant protector of children in 1955’s eerie Night of the Hunter. Two years earlier, she had created the role of Mrs. Carrie Watts in The Trip to Bountiful, written by Horton Foote. Foote specialized in deceptively simple tales of small-town Texas folk, using legends from his own family to create a cavalcade of memorable characters. His TV play about an elderly woman, stuck living with relatives in Houston but longing for the country comforts of her past, proved so popular that it soon was expanded for the Broadway stage, with Gish repeating her starring role.

In 1985, The Trip to Bountiful finally became a Hollywood film, with Geraldine Page (a mere 61) winning a Best Actress Oscar. Twenty years later, Horton Foote’s daughter Hallie—herself an actress—appeared in a supporting role in an Off-Broadway revival. It was Hallie who in 2013 was inspired to produce the play with a largely African-American cast. I’m not aware of anything in the text being changed, but Foote’s play takes on new resonance when an old black woman, determined to return to her childhood home by whatever means, is forced to interact with a white ticket-seller and white sheriff. And of course this version hugely benefits from the presence of a truly ageless actress, Cicely Tyson.

Tyson, who started out as a high-fashion model, made a Hollywood splash in Sounder, a family drama about black sharecroppers scrambling to survive the Great Depression. For that 1972 film she was nominated for a Best Actress Oscar; Diana Ross was also up that year for Lady Sings the Blues, making them the first two African-American women to be nominated since Dorothy Dandridge in 1954’s Carmen Jones. Though she took home no statuette then, Tyson soon won her first of many Emmys for The Autobiography of Miss Jane Pittman. The Trip to Bountiful has given her a Tony award to add to her collection. At 81, or maybe older, Tyson displays physical stamina as well as a complex range of emotions. It’s wonderful to see an old woman being treated on stage with such respect.

This post is lovingly dedicated to Estelle Gray (1918-2014), truly a woman of valor. Mom, here’s hoping you’ve reached your own Bountiful now.

Published on November 07, 2014 09:00

November 4, 2014

Casting a Ballot in Movieland

Cindy Crawford phoned me last evening. Yes, I’m talking about Cindy Crawford the supermodel. But I can’t pretend that she and I are close chums. She was phoning to tell me that she has kids in my local school district (who knew?), and that I should think about voting for the school board candidate of her choice. Personally, I have little interest in Cindy’s preferred school board member. The Santa Monica-Malibu Unified School District serves my city and also the much tonier enclave up the coast. I’m not much inclined to give Cindy and her beachfront neighbors their own handpicked representative.

All across the country, elections bring out superstars, whether political stars like Bill Clinton or showbiz celebrities. Pop music icon Carole King, for one, has shown up in my email in-box, urging me to donate on behalf of several candidates for the U.S. Senate. Here in California, singer-songwriter John Legend is stumping for Marshall Tuck, who hopes to be the next State Superintendent of Public Instruction. And such movieland insiders as Matt Damon and Norman Lear are backing with serious bucks a candidate for State Assembly with the unlikely name of Prophet Walker. Walker, who hopes to represent a blue-collar district encompassing Compton and Watts, has a life story seemingly made for Hollywood. The son of a birth mother who succumbed to heroin addiction when he was still an infant, he grew up in South Central L.A. At sixteen, he was convicted of armed robbery, then sentenced to six years in prison. It was while behind bars that he began an unlikely turnaround that led him to graduate from college and embark on a career as a community activist. If he wins his race, his story will have a true Hollywood ending.

But Hollywood is more than superstars and the intriguing underdogs whose up-from-the-gutter stories would make for a great movie-of-the-week. There are also those unionized behind-the-scenes crew members who are worried that their jobs are being outsourced to New York, New Mexico, and Canada. My good friend Ben Allen, an outstanding candidate for State Senate, has circulated a mailer that trumpets his endorsement by all Los Angeles-area locals of IATSE, the international union representing film and TV production folk. He’s also won the support of Councilman Paul Krekorian, author of the first California bill to establish an entertainment tax credit for the Golden State.

Similarly, one would-be L.A. County Supervisor, Bobby Shriver, has sent out flyers emblazoned with a vintage photo of a movie premiere on Hollywood Boulevard. The text reads: “We Founded the Movie Industry. Let’s Bring Our Jobs Back.” He also lets it be known that among his staunch supporters is Steven Spielberg, along with several Kennedys. Shriver’s opponent, Sheila Kuehl, enjoys playing up her own Hollywood connection. Back in the day (before law school and years of service in the California State Senate) she was Sheila James, who memorably played plucky little Zelda Gilroy on The Many Loves of Dobie Gillis.

Over the years, Hollywood has had its own fun with movies about politics. Among the best, of course, is Frank Capra’s Mr. Smith Goes to Washington, in which idealism triumphs over the schemes of corrupt politicians. Much more cynical is Preston Sturges’ The Great McGinty. I loved Alexander Payne’s wicked 1999 high school satire, Election, in which a campaign for student body president ends up laying bare what can happen when a candidate who will stop at nothing (Reese Witherspoon) takes on her high-minded civics teacher (Matthew Broderick).

As for Election Day 2014, may the best man (or woman) win. Go Ben!

Published on November 04, 2014 14:29

October 31, 2014

“Shock Value”: Shock and Awe on Halloween Night

Be afraid, be very afraid . . . the witching hour approaches! Here in L.A. there are multiple ways to celebrate. If you’re the arty type, perhaps you showed up at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art dressed as your favorite painting, then checked out an exhibit called “Haunted Screens: German Cinema in the 1920s” before dancing the night away. The funky Ace Hotel downtown offered a screening of John Carpenter’s classic Halloween, followed by the live performance of a band called Slasher Flicks. (Its website is well worth a gander.) In many a suburban neighborhood, residents who make their living on film crews enjoyed scaring the local kids with home-grown haunted houses. Guaranteed: a creepy good time.

Or you could stay indoors and read Shock Value: How A Few Eccentric Outsiders Gave Us Nightmares,Conquered Hollywood, and Invented Modern Horror. This well-researched 2011 study by New York Times writer Jason Zinoman admirably explains how the scary movies of the 1970s differed from what had come before. Hollywood horror used to mean Boris Karloff as a misunderstood Frankenstein monster, or else Roger Corman directing Vincent Price in an Edgar Allan Poe adaptation. In other words, costume drama with psychological underpinnings and a soupçon of the supernatural. Zinoman argues that by the seventies horror flicks had become both more realistic and more ambiguous, anchored by a wholly unknowable monster. He begins his book, aptly enough, with a quote from Wes Craven: “The first monster that an audience has to be scared of is the filmmaker. They have to feel in the presence of someone not confined by the normal rules of propriety and decency.”

In each of his chapters, Zinoman focuses on a key horror film of the era, tracing its origins and implications. There’s Rosemary’s Baby, of course, and Night of the Living Dead, followed by Last House on the Left, The Exorcist, Carrie, The Texas Chain Saw Massacre, and Alien. Zinoman proves especially acute when discussing Carpenter’s Halloween, which spawned scores of imitations after it proved that “cheap horror could be big business.” He has high praise for Halloween’s stripped-down piano score and for its much-imitated bravura opening tracking shot, in which we see through the killer’s eyes as he zeroes in on his prey. Zinoman claims that Michael Myers represents a radically new kind of monster: “The monster has traditionally been a stand-in for some anxiety, political, social, or cultural. But Myers doesn’t reveal anything. He wears a mask, but there is nothing of importance under it.” In the original Halloween (in contrast to its later follow-ups), Myers’ actions cannot be explained. Instead he’s a blank, a bogeyman. This fits with Zinoman’s thesis that “the central message of the New Horror is that there is no message. The world does not make sense. Evil exists, and there is nothing you can do about it.”

One of Michael Myers’ most distinctive characteristics is that he does relatively little: “Michael Myers doesn’t jump into the screen, and while he certainly attacks with a variety of knives, he is at his most threatening standing still, just looking.” Zinoman quotes Carpenter himself on the source of this inspiration: “There was a movie called The Innocents made in the sixties where ghosts were standing across a pond, just looking. Doing nothing but looking.” I too saw The Innocents back in the day. This Deborah Kerr film, directed by Jack Clayton, was based on Henry James’ The Turn of the Screw. It terrified me then, and I haven’t dared watch it since.

I wish Jason Zinoman, and everyone, a happily haunted Halloween.

Published on October 31, 2014 22:47

October 28, 2014

Lullaby of Birdman (aka Gone Guy)

Two of today’s most talked-about films, Gone Girl and Birdman or (The Unexpected Virtue of Ignorance), both focus on the hot topic of media celebrity. Gone Girl dramatizes the way members of the viewing public, egged on by TV commentators with biases of their own, choose up sides when faced with scandal or crime of a particularly heinous nature. If you’re unlucky enough to be featured on a TV news broadcast, you’ll inevitably find yourself typecast as either a villain or a victim. And you’ll discover along the way that changing public perception is by no means easy.

Birdman – which appealed mightily to my sense of humor and sense of wonder – concerns itself with the world of actors. It belongs in the category of movies (including everything from Forty-Second Street to Woody Allen’s Bullets Over Broadway) that chronicle the staging of a Broadway play, taking us behind the scenes to meet actors with large egos and larger insecurities. In Birdman, there’s a priceless performance by Ed Norton as a cocky Broadway Method actor, and an appealing one by Naomi Watts as a fading Hollywood beauty both thrilled and alarmed at the prospect of making her debut on the Great White Way.

But Birdmanbelongs to Michael Keaton, whose long career includes outrageous roles in two early Ron Howard comedies (Night Shift and Gung Ho). Also in the 1980s, he starred in the popular role-reversal comedy Mr. Mom, then put on the cape and mask for Tim Burton’s Batman. The latter film surely helped prepare him for Birdman: in it he plays a former Hollywood he-man who, having once walked away from the fourth film in a popular superhero franchise, now wants to revive his reputation by presenting himself as a serious New York actor/director/playwright. His stage adaptation of a grimly realistic Raymond Carver short story couldn’t be more different from the films in which he made his name. The joke is that, though Broadway insiders scorn Keaton’s character as an over-the-hill interloper, the public still considers him royalty. That’s why they’re ready to respect anything he does, however misguided. It seems that playing a caped crusader on the big screen is clearly a form of godliness.

I won’t go into the many surprises that grace Alejandro González Iñárritu’s film, except to praise the way he balances magical moments with the nitty-gritty of the New York theatre world. We see a lot of an actual 44th Street theatre, whose cramped backstage hallways and grimy dressing rooms belie the glamour most of us associate with Broadway. The script, which convincingly portrays the tangle of emotions most actors know all too well, also has fun with insider references ranging from Robert Downey Jr.’s superhero chops to Meg Ryan’s plastic surgeon.

In this context it’s worth noting that the number of Hollywood legends who look for legitimacy on the Broadway stage continues to rise. In the recent past, Scarlett Johansson has trod the boards in Tennessee Williams’ Cat on a Hot Tin Roof, and Tom Hanks just starred in an original called Lucky Guy. Daniel Radcliffe, trying to shed his Harry Potter mantle, has done everything from a musical (How to Succeed in Business) to a take-your-clothes-off drama (Equus). Michael Cera is currently wowing critics in This is Our Youth, but not every Hollywoodite receives serious critical respect. The public, though, remains starstruck.

During the annual Tony Awards ceremony, honorees continue to imply that acting on a Broadway stage is somehow far more noble than mere movie-making. Still, Hollywood celebs sell tickets, and New York seems happy to let their stars shine bright.

Published on October 28, 2014 11:34

October 24, 2014

All Ben Bradlee’s Men

It’s hard to believe that Ben Bradlee has left us. I always pictured Bradlee, the longtime executive editor of the Washington Post, as something like the figures on Mt. Rushmore: unmovable and eternal. What a shock to learn that this brilliant and feisty man succumbed last Tuesday, at the age of 93, to the ravages of Alzheimer’s disease.

Benjamin Crowninshield Bradlee started life as a Boston blueblood, with a direct connection to wealth and power. He was by all accounts a charismatic leader, one whose mannerisms and sartorial style (slicked-back hair, striped shirts) were imitated by generations of rising journalists. But he was also a man of courage. A champion of modern investigative journalism, he re-made the lackluster Post as a gutsy newspaper that skewered the Nixon administration by publishing the Pentagon Papers and then blowing wide open a little caper called Watergate. As a direct result of stories first published in the Washington Post, Richard M. Nixon resigned the presidency on August 9, 1974.

Of course the enterprising newsmen who investigated the 1972 break-in at the Democratic National Committee’s D.C. headquarters were Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein. At the time, they were lowly reporters following a hunch that the Watergate burglars were backed by someone high in the Nixon White House. Over the course of two years the pair became America’s most famous newspapermen, as well as models for a generation of young journalism students eager to uncover political wrongdoing wherever they found it. Woodward and Bernstein’s newfound celebrity was reinforced by a book they published in 1974, All the President’s Men. And this book quickly led to an immensely popular film of the same name, in which the chief roles were played by two of the industry’s brightest young leading men, Robert Redford (Woodward) and Dustin Hoffman (Bernstein).

A breathless political thriller, All the President’s Men was nominated for eight Academy Awards, including Best Picture. It was beaten out of the top prize by Rocky, but won four Oscars, including Best Adapted Screenplay ( by Hollywood legend William Goldman) and Best Supporting Actor. This latter award went to the great Jason Robards, for bringing Ben Bradlee so vividly to the screen.

Bradlee was also impersonated in other films. He was played by G.D. Spradlin in Dick, a wacky little 1999 comedy in which two high school girls who wander away from a school trip to Washington meet President Nixon, and come to advise him on handling the Watergate scandal. (For the record, the two girls were Kirsten Dunst and Michelle Williams, while the role of Bob Woodward was given to none other than Will Ferrell.)

I can think of at least two more Hollywood films that connect, in one way or another, with the Watergate era. The first involves Carl Bernstein, who was married to writer-director Nora Ephron from 1976 to 1980. Ephron later fictionalized their marriage, including Bernstein’s disastrous extramarital fling, in the darkly comic Heartburn, a bestselling novel that later became a movie starring Jack Nicholson and Meryl Streep. And let’s not forget the shadowy informant who gave Woodward and Bernstein the key to the Watergate mystery. In the reporters’ book, this Nixon administration higher-up who spilled secrets in a Washington parking garage was nicknamed Deep Throat. Needless to say, Deep Throat was the title of a hugely popular soft-core porn flick (1972) in which Linda Lovelace demonstrated a very unusual talent.

I’m not sure how Ben Bradlee felt about that connection. But, wherever he is, I wish him well.

Published on October 24, 2014 09:02

October 21, 2014

Dan O’Bannon: Real Horrorshow

Halloween is coming, which means scary movies on everyone’s radar. Last week I was invited to the USC Film School to see a documentary titled Shock Value: The Movie—How Dan O’Bannon and Some USC Outsiders Helped Invent Modern Horror . This assemblage of USC student films circa 1970 provides a riff on Jason Zinoman’s Shock Value, a fascinating book on the evolution of contemporary American horror films that I’ll revisit as October 31 creeps near. I was enthralled by my glimpse of student work in the early 1970s, full of sex, miniskirts, and endless cigarettes. (The level of violence, though, was tame indeed, even by today’s TV standards.)

These days, USC’s film school—the nation’s oldest—is housed in palatial digs built by George Lucas and other Hollywood royalty. But in Dan O’Bannon’s era, film students mingled in a ramshackle former stable. Everyone knew everyone, and they all knew Dan O’Bannon, who was probably both the weirdest and the most multi-talented of the film geeks. O’Bannon could do it all: writing, directing, acting, special effects. But, as a post-screening panel made crystal-clear, he was not an easy guy to be around. For one thing, he would never suffer a fool . . . or a bad movie. At student screenings in the hallowed Room 108, he could be blunt when criticizing the work of his classmates. And his private life was turbulent. He kept by his bedside a huge stack of porn , topped by a wicked-looking .45.

The evening at USC was essentially a tribute to the work of O’Bannon, who’s best remembered today as the writer of Alien. (He also directed such Hollywood hits as The Return of the Living Dead, but succumbed to Crohn’s disease in 2006.) The documentary kicked off with his funny and gruesome Blood Bath, in which a young man bumbles from a morning-after hangover to a death most bloody. Dan’s acting chops (as well as his makeup skills) were also on display when he impersonated an elderly codger in the futuristic Good Morning, Dan. Most memorably, in Judson’s Release -- which was later renamed Foster’s Release -- he played a maniacal stalker, harassing a pretty babysitter over the telephone before making a deadly in-person appearance.

Sound familiar? Author Jason Zinoman applauds this student film (directed by my future Roger Corman buddy Terence Winkless) for establishing the horror tropes that we associate with John Carpenter’s big breakthrough movie, Halloween. No surprise: O’Bannon and Carpenter were USC classmates, who together had their first taste of success with the spoofy sci fi flick, Dark Star. This student film was snapped up by Hollywood and expanded into a feature, with O’Bannon on camera (eluding the fearsome tomato monster) as well as collaborating with Carpenter on the script. When they hit the big time, though, Carpenter was only too happy to dump his old pal. It was clear from all of the evening’s speakers that John Carpenter is not the most generous of men.

Of course, that’s the way Hollywood operates, and in later years Dan O’Bannon suffered his share of betrayals. He had to fight for credit on screenplays he had originated, and (according to an elaborate story that was told from the stage) the great Orson Welles apparently swiped one of his story ideas. Others have gotten far richer, but his widow Diane insisted that “what he cared about was the work . . . and the audience.” Diane knew Dan for 17 years before they married, by which time he had mellowed from a weirdo into “a fusty old guy with a very big heart.”

Published on October 21, 2014 18:45

Beverly in Movieland

I write twice weekly, covering topics relating to movies, moviemaking, and growing up Hollywood-adjacent. I believe that movies can change lives, and I'm always happy to hear from readers who'd like t

I write twice weekly, covering topics relating to movies, moviemaking, and growing up Hollywood-adjacent. I believe that movies can change lives, and I'm always happy to hear from readers who'd like to discuss that point.

...more

- Beverly Gray's profile

- 10 followers