Beverly Gray's Blog: Beverly in Movieland, page 112

February 27, 2015

Selma: The Whole World Was Watching

Now that the Oscar ceremony is over, the sound and fury surrounding the movie Selma has largely subsided. All the points of controversy, among them the film’s take on President Lyndon Johnson and the failure of the Academy to nominate director Ava DuVernay and star David Oyelowo, are now pretty much moot. Certainly, I was as surprised as anyone that Oyelowo won no nomination for his stirring, convincing portrait of Dr. Martin Luther King. In a year when the portrayal of real-life heroes (Alan Turing, Stephen Hawking, Chris Kyle) was being richly rewarded by those with prizes to give, Oyelowo’s work certainly merited recognition. Which was why, of course, the Oscar broadcast was at pains to feature Oyelowo throughout the evening. (I’ve got to say—I loved that maroon tuxedo.)

With the question of statuettes now out of the way, I should add that I’m deeply grateful for Selma. Not so much for its aesthetic achievements, mind you, as for its contribution to the historical record. Needless to say, no feature film can ever hope to be 100% accurate. In telling a story that will connect with viewers over a two-hour period, filmmakers necessarily cut corners and make mental leaps. Still, even those of us who were alive during that tumultuous era need reminding of what happened, and why it did. One key function of movies is to give us visual images that allow the past to live on. With Black History Month just wrapping up, it seems high time to salute Selma for putting before our eyes (even in a necessarily truncated form) what went down on Alabama’s Edward Pettus Bridge in March 1965. What happened fifty years ago has much to teach us about today’s racial divide, and I thank DuVernay and company for the memories.

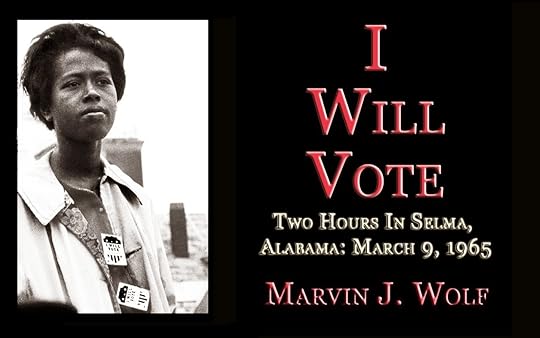

My viewing of Selma is part of why I approached Marvin J. Wolf’s recent publication, I Will Vote , with excitement. Wolf, a veteran journalist and my colleague in the Southern California chapter of the American Society of Journalists and Authors, started out as an aspiring U.S. Army combat photographer. In early March 1965, because the Army needed him at Fort Benning, Wolf headed in his own car from Los Angeles to Georgia via U.S. Highway 80. His route took him through Montgomery, Alabama. As he approached Selma, fifty miles west of Montgomery, on the morning of March 9, he was surprised to see this normally sleepy country town crawling with cops. He soon learned that Dr. King was in the vicinity, supporting a voting rights demonstration that had quickly turned ugly. (Around the time Wolf arrived, a white Unitarian minister named James Reeb died from injuries inflicted by white racists who’d been deputized by Jim Clark, the notorious sheriff of Alabama’s Dallas County.)

Wolf had with him only three rolls of film. (Remember film cameras?) He shot as many photos as he could, capturing the image of neatly-dressed black protesters, solemn-faced white clergy, alert news reporters, and policemen feeling the heft of their nightsticks. Wolf was particularly taken by the earnest face of a black female college student wearing a button that announced, “I will vote.” Then a rock was thrown in his direction, and a giant of a deputy in bib overalls knocked him to the ground. He prudently left town, and those three rolls of film were forgotten for almost fifty years. How fascinating to see now what he captured then.

By the way, Marv has another new non-fiction book out, Abandoned In Hell, The Fight For Vietnam's Firebase Kate. Old journalists never die . . . thank goodness!

To look at the Civil Rights era from another perspective, check out my colleague James McGrath Morris’s new Eye on the Struggle: Ethel Payne, the First Lady of the Black Press. It’s gotten terrific reviews, and I look forward to reading it myself.

Published on February 27, 2015 12:09

February 24, 2015

Oscars 2015: Staying Weird, Staying Alive

So another Oscar ceremony is in the books. I’m not unique, I’m sure, in finding my greatest satisfaction in the unexpectedly pointed remarks of many of the winners, as they received their statuettes for films that touched (however lightly) on serious matters. There was Patricia Arquette’s shout-out in favor of equal pay for women, which elicited Meryl Streep’s enthusiastic “You go, girl!” There was Eddie Redmayne, honored for playing Stephen Hawking, symbolically giving his award to Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis sufferers (though he made clear the Oscar would live at his house). Soon afterward, winner Julianne Moore was equally eloquent about the need to find a cure for Alzheimer’s disease. Triple-winner Alejandro González Iñarritu needled the audience about immigration issues, and the writers of “Glory” (the Oscar-winning song from Selma) both sang and spoke so powerfully about civil rights that it was no surprise to see Academy members with tears rolling down their cheeks.

Even yawn-worthy categories like Best Documentary Short Subject led to poignant speeches. I had not heard of Crisis Hotline: Veterans Press 1, but the words of its co-directors will stay with me, especially Dana Perry’s mention of the son that died by his own hand, and her plea that “We should talk about suicide out loud.” Who would have guessed that an hour or so later, Graham Moore—accepting a screenwriting Oscar for The Imitation Game—would announce that at age sixteen he too had tried to kill himself, “because I felt weird and I felt different and I felt like I did not belong.” He addressed himself directly to “that kid out there who feels like she’s weird or she’s different or she doesn’t fit in anywhere. Yes, you do. I promise you do. Stay weird, stay different, and then when it’s your turn and you are standing on this stage, please pass the same message to the next person who comes along.”

As always, a memorable (though somber) part of the evening was dedicated to those Hollywood figures who had passed away since last year’s ceremony. The painter who’d provided portraits of the deceased beautifully captured the exuberance of Geoffrey Holder, the husband of my very first dance teacher. And I was moved to see recognition for others I’d interviewed over the years: cinematographer Gordon Willis, screenwriter Lorenzo Semple Jr., and particularly Charles Champlin, veteran film critic of the Los Angeles Times.

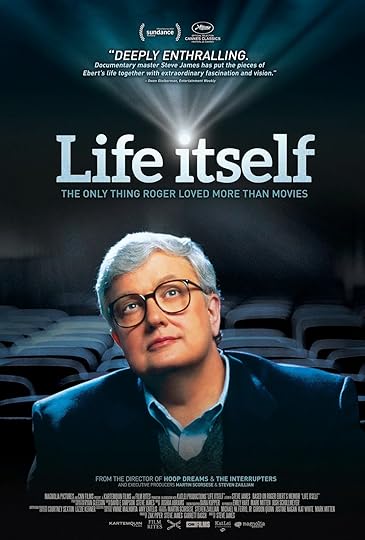

Hollywood generally doesn’t love movie critics (though Life Itself, a documentary feature about the life and career of the late Roger Ebert, was short-listed for one of this year’s nominations.) But the film industry had a rare affection for Charles Champlin, who was considered both knowledgeable and fair-minded. By the time I interviewed Champlin in 2008, he was long retired and suffering from health issues. When I asked about the films of the Sixties, he simply didn’t remember certain matters on which he had once boldly taken a stand. I came home with one of his books, The Movies Grow Up: 1940-1980, which begins by explaining that “my generation grew up with the movies and without television. The movies entertained us, inspired us, consoled us, shaped us profoundly; taught us (although not invariably wisely or well) and attempted to spare us from some bitter truths about the world.” By the time I met Champlin, though, he was thinking less about movies than about, well, life itself: “The world slips away from us very fast, I think. It’s like sand through your fingers. You think you’ve got it all in your hand, but it’s gone through your fingers.” Rest in peace, Chuck.

Coming soon: on Saturday, May 2, 2915, I'll be on a panel discussing "The Secrets of Interviewing Famous People." It's part of the American Society of Journalists and Authors annual three-day conference in New York City. Click here for more info.

Published on February 24, 2015 13:19

February 20, 2015

The Many Faces of Robert Forster

Back in late December, when Christmas music was in the air, I breakfasted with Robert Forster at his favorite West Hollywood café. Oscar season was just heating up, and our chat turned to the possibility that showbiz veteran J.K. Simmons might score a Best Supporting Actor nomination for his role in Whiplash. We agreed that any honor coming to Simmons at this point in his career would be a tribute to the years he’s spent paying his dues within the industry. Said Forster, emphatically, “This guy deserves that, and he will get it. I’d say it’s a foregone conclusion that he’s gonna get his turn.”

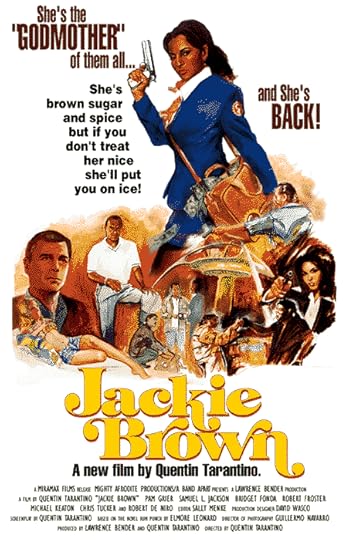

Forster can easily put himself in Simmons’ shoes, because in 1998 he was nominated in the Best Supporting Actor category for Jackie Brown. The accolade from his peers, arriving “quite out of the blue,” filled him with “a feeling of warmth that was unexpected.” It had been a long time since his glory days as a handsome young rising star, and “I thought I was by then forgotten. . . . You know, to catch a little warmth near the end is a nice place to get it.”

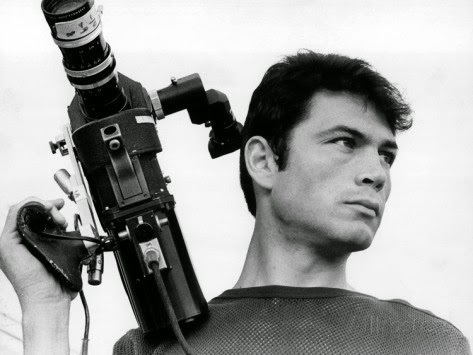

Though Forster freely admits he’s not going to be People Magazine’s next Sexiest Man Alive, he’s hardly finished with his acting career. He may be over seventy, but interesting character parts keep coming his way. There was a time, however, when he seemed to be scraping bottom. Back in 1967, he had made his film debut under the direction of John Huston. For five years he played important dramatic roles in acclaimed Hollywood productions like The Stalking Moon and Medium Cool. He’s philosophical about his fall from grace: “There is a constant push of new people coming in who get the attention of an agent who goes to town and tries to promote them. There’s only so many jobs, and everybody is trying to find room for their clients in those few jobs.” Still, he had a family to support, and it was tough being relegated to the occasional TV episode and Roger Corman flick.

That’s why, after twenty-five years of struggling, he’s grateful to Quentin Tarantino for returning him to the limelight as good-hearted bail bondsman Max Cherry in Jackie Brown. (As he puts it, “I was dead, and this guy gave me life.”) He’s also grateful to Alexander Payne, who cast him in the small but meaty part of George Clooney’s father-in-law in The Descendants. Which, in turn, led to his memorable appearance in Breaking Bad. Not one to blow his own horn, he describes himself as “a very lucky guy.”

Certainly, his start as an actor was remarkably lucky. Accompanying a friend from acting class to see an agent, he ended up featured in a Broadway play. And suddenly John Huston was asking to meet with him for an important dramatic role in Reflections of a Golden Eye, starring Elizabeth Taylor and Marlon Brando. Forster admitted to Huston, “I never made a movie, I don’t know how they’re made, I don’t know what the tricks are, but if you hire me I’ll give you your money’s worth.” Next thing he knew, he was in Rome, riding naked on a big white horse.

(Forster does a capital imitation of the deep-voiced Huston explaining to him, just before the cameras rolled, the essence of screen acting. Suffice it to say: “He gave me the responsibility and the authority to deliver whatever is needed inside that frame.”)

Is there a typical Robert Forster part? “I always say, whatever comes next is a surprise. It’s always a surprise.”

Publicity Shot for "Medium Cool" (1969)

Publicity Shot for "Medium Cool" (1969)

Published on February 20, 2015 09:14

February 17, 2015

Fifty Shades of Beverly Gray

After a weekend that’s been . . . uh . . . dominated by Fifty Shades of Grey, I can’t resist submitting a Valentine to my many namesakes, the Beverly Grays of the world.

Beverly Gray is the moniker I was given at birth. To be honest, the surname Gray does not go very far back in the annals of my family. When my father was a young man, his parents legally simplified the name they’d brought with them from the Old Country. Though not a bad name, it was longer and far more difficult to pronounce than the all-American “Gray.” (I doubt they realized how often it would be misspelled.)

When my mother married my father, she was delighted by the simplicity of her new last name. My given name, Beverly, honors some long-lost relatives, but I suspect it also reminded my parents of Southern California’s glamour locations: Beverly Hills, Beverly Glen, Beverly Boulevard. Just by happenstance, we ended up in a subdivision called Beverlywood. And one day, when I was still tiny, my parents were surprised to spot a young-adult novel titled Beverly Gray’s First Romance. It turns out there were 26 entries in the Beverly Gray Mystery series, published by Clair Blank between 1934 and 1955. Beverly was a beautiful (of course) red-headed reporter -- someone on the order of Nancy Drew, though slightly older -- who solved mysteries and tracked down criminals all over the world. As a budding journalist myself, I enjoyed scouting out these volumes, which today are considered collectors’ items. It’s slightly embarrassing to me now that if you do a Google search on my name, most of the references are to my literary alter-ego.

But the Internet shows me there are living Beverly Grays too, along with a number of dead ones. (I’ve stumbled across several obits.) Some are writers, among them the Beverly Ann Gray who has written a number of scholarly books about present-day Africa, like The Nigerian Petroleum Industry, A Guide. I’ve also discovered, via Amazon, a Beverly C. Gray who keeps churning out volumes in the Black Knights of the Hudson series, and another Beverly Gray (definitely not me) who has published The Boreal Herbal: Wild Food and Medicine Plants of the North.

The Beverly Gray who wrote and marketed sentimental verse seems to have disappeared from view. But I often see references to a Beverly Gray who’s respected as the coordinator of the Southern Region Ohio Underground Railroad Association, headquartered in Chillicothe, Ohio. I once got a friendly email from a Beverly Gray in Florida. Presumably she’s not the Beverly Gray who was arrested in that state on April 23, 2014. (I have a link to her mugshot.) I’m pleased there’s a Dr. Beverly Gray who’s an obstetrician in Raleigh, North Carolina, but I don’t know how I feel about the Beverly Gray who’s married (according to Twitter) to an “Awesome Man of God.” One Beverly Gray is a cello teacher in Scotland, while another is a prize-winning equestrienne in Utah. Facebook tells me that Beverly Grays go to church, like the Atlanta Center for Cosmetic Dentistry, groove to Willie Nelson, work for the IRS, and are students of the University of Life.

If you’re in show biz, it’s important to have a name that’s unique, which is one reason some actors shed their birth names. (Julianne Moore, for instance, was born Julie Smith, but discovered another professional actress had gotten there first.) On the Internet Movie Database, I’m happy to be the only Beverly Gray. But there’s actually a crew guy named Gray Beverley. Go figure.

Published on February 17, 2015 10:06

February 13, 2015

Pride and Prejudice, without Zombies or Peacock Feathers

In the era of Fifty Shades of Grey, the romantic tales of Jane Austen must seem awfully tame. Still, I’ve been on a Pride and Prejudice kick lately, and the advent of Valentine’s Day is the perfect moment to contemplate the innocent side of romance. The time is also ripe because I’m now preparing to lead a community discussion as part my local library’s annual Santa Monica Reads program. The book this year is Longbourn, Jo Baker’s 2013 retelling of Pride and Prejudice from the perspective of the Bennet family’s servants. Longbourn, which I’d personally categorize as educated chick lit, contains some of the upstairs/downstairs social tensions that have drawn many of us to Gosford Park, and more recently Downton Abbey. Longbourn is instructive, mildly steamy (especially when there’s laundry to be done), and presents some uplifting grand passion among the lower orders. But, truthfully, I’d prefer Pride and Prejudice any day.

Hollywood has always been fond of the romantic sparring between the proud Mr. Darcy and the spirited Elizabeth Bennet, who thinks the worst of him from the moment he arrives in her little village and sneers at the locals. I have a strong affection for the Golden Age version, directed by Robert Z. Leonard, in which Laurence Olivier and Greer Garson play the lovers, and Edmund Gwenn (best known for portraying Santa Claus in the original Miracle on 34th Street) is Lizzy’s properly whimsical father.Yes, I must admit that Garson, though completely charming, is much too old to play Elizabeth. In 1940, when this film was released, she was 36, though Austen’s character admits in passing that she’s not yet one-and-twenty. But Olivier makes the perfect Darcy, and Edna May Oliver is hilariously obnoxious as the stuffy Lady Catherine de Bourgh, whose outspoken disapproval of the match ironically ends up furthering it.

It took over sixty years for another big-screen version to surface. The Elizabeth of Joe Wright’s 2005 version was aptly played by the dewy yet spunky twenty-year-old Keira Knightley, with Matthew McFadyen as her Darcy. Who better than Judi Dench in the Lady Catherine role? Others involved included Donald Sutherland and Brenda Blethyn as Lizzy’s mismatched parents. I was amused to discover that her angelic sister Jane was played in this version by Rosamund Pike, far removed from her Amy Dunne character in Gone Girl. And Carey Mulligan, in her first film appearance, was cast as one of the lesser Bennet sisters. Knightley earned herself an Oscar nomination for this film, which was also honored for its music, art direction, and costume design. But true fans of the novel are particularly fond of 1995’s serialized BBC television version, starring Jennifer Ehle and Colin Firth.

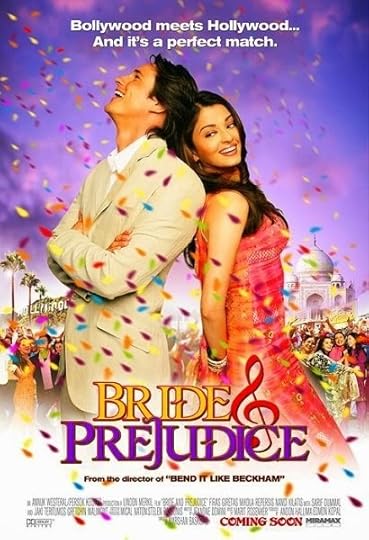

The story of Pride and Prejudice is so well loved that it has also shown up in some multicultural versions. I refer you to Bride & Prejudice, an oddball adaptation from 2004 obviously intended to capitalize on the Bollywood craze. In Bride & Prejudice, Lizzy Bennet is transformed into Lalita Bakshi (played by the gorgeous Aishwarya Rai), one of five daughters in a modern-day Hindu family. Her Mr. Darcy is an American (Martin Henderson), cocky scion of a wealthy family, who shows up in her quaint Indian town with plans to build a big, bad hotel chain. The plot sticks fairly closely to Austen’s original, except that at one point the main characters are whisked away to L.A., where they sing and dance in inimitable Bollywood fashion in front of Disney Hall and other SoCal landmarks. I suspect that Jane Austen would have been puzzled, and then highly amused.

The public is cordially invited to all Santa Monica Reads events. Y’all come!

Published on February 13, 2015 10:54

February 10, 2015

Forget Me Not: The Elusive Lines of Michael Gambon

Sad news on the theatre front. Sir Michael Gambon, one of those magisterial British actors who do so well in part that require innate dignity, is retiring from the stage. Moviegoers best remember Gambon for taking over the role of Albus Dumbledore in the Harry Potter films, following the death of Richard Harris. But he’s been making movies since he played a spear-carrier in Laurence Olivier’s 1965 cinematic adaptation of Othello. I remember him in Gosford Park and in Dustin Hoffman’s directorial debut, Quartet. Yet the classically trained Gambon, a graduate of the Royal Academy of Dramatic Arts, was first and foremost a stage actor. Over a period of 53 years, he’s performed the plays of Shakespeare, Chekhov, and Samuel Beckett. Simon Callow, a fine actor himself, has hailed Gambon for his ability to conquer the enormous main stage of Britain’s National Theatre: “Gambon's iron lungs and overwhelming charisma are able to command a sort of operatic full-throatedness which triumphs over hard walls and long distances.”

Recently, though, Gambon has butted up against a problem that is death to any stage performer. Now in his seventies, he suffers from short-term memory loss that has made him struggle to remember his lines. In 2009 he twice succumbed to panic attacks during rehearsals, because the words just wouldn’t come. Extensive medical tests cleared him of any sign of Alzheimer’s, but that didn’t make his plight any easier. He tried to avoid stage roles requiring massive amounts of dialogue, and finally went so far as to try wearing a prompt ear-piece while rehearsing a West End show. As he put it, “There was a girl in the wings and I had a plug in my ear so she could read me the lines. After about an hour I thought, ‘This can’t work.’ It’s a horrible thing to admit but I can’t do it. It breaks my heart.”

Fortunately for the rest of us, Gambon plans to continue on with his stellar film and television career. His situation accentuates some key differences between stage and screen performance. Movies are made in fits and starts: you rarely speak more than a few snippets of dialogue at a time, and when things go awry, do-overs are always possible. What’s exciting about live theatre is its continuous flow. Stage actors shaky in their lines can’t stop and correct themselves, nor look to someone in the wings for help. Yes, there are moments when even the most experienced performer “goes up” (as the British say) on his or her lines, but such flubs must be overcome without the audience realizing that anything’s amiss. No wonder that actors find the stage so exhilarating, and also so scary. It’s a high-wire act, which is why some of the greatest performers of all times have suffered from debilitating stage fright. Gambon’s problem is sadder still, in that it seems to be physical as well as psychological. But at least we’ll be able to enjoy him in a medium that often depends more on powerful close-ups than on the ability to master long strings of polysyllabic words.

Speaking of movies, one of 2014’s oddities is the fact that writer-director Alejandro González Iñárritu chose to shoot Birdman as though the entire film were one continuous take. This required meticulous rehearsal, and a cast committed to seizing the moment. Featured actress Emma Stone describes the process: “There was no luxury of cutting away or editing around anything. You knew that every scene was staying in the movie, and like theater, this was it, this was your chance to live this scene.”

Published on February 10, 2015 12:17

February 6, 2015

Light & Noir: Exiles and Émigrés in Hollywood

What do Casablanca, To Be or Not to Be, Sunset Blvd., Ninotchka, Double Indemnity, and Harvey have in common? Yes, all are classic movies from the Golden Age of Hollywood. But beyond that, all were made by filmmakers (with names like Michael Curtiz, Ernst Lubitsch, Billy Wilder, and Henry Koster) who’d fled Europe when the Nazis came to power. The legacy of these filmmakers is explored in a fascinating exhibit at the Skirball Cultural Center in L.A.’s Sepulveda Pass (through March 1). It’s called Light & Noir: Exiles and Émigrés in Hollywood, 1933-1950.

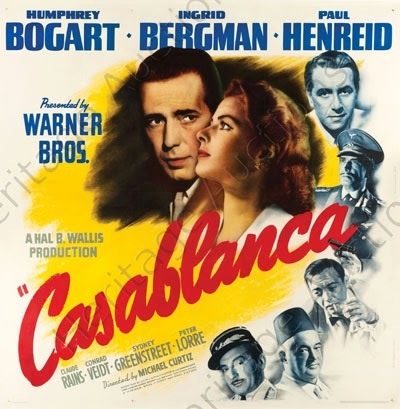

It wasn’t just movie directors who made their way to Hollywood from Berlin and Budapest and Vienna. As the exhibit points out, Hollywood also became a new home for European producers, screenwriters, composers (like Max Steiner and Miklos Rózsa), and technicians, along with countless actors. Casablanca, directed by Michael Curtiz, takes advantage of such new arrivals as Peter Lorre, Paul Henreid, Conrad Veidt, and S.Z. Sakall, whose varied accents give the film a genuinely international flavor. One irony: actors who had fled from Nazism often found themselves impersonating Nazis on the screen.

The point of the exhibit’s title is that the newcomers made their mark both in lightweight comedies and in dark film noir thrillers. The latter, often marked by shadows and striking camera angles, owed a strong debt to the German expressionist tradition. But the curators point out that there’s surprising overlap between sparkling trifles like The Major and the Minor and the era’s film noir masterpieces. In all of them there tends to be an emphasis on deceptions, stolen identities, and masquerades: a way of life that most refugees knew all too well.

Many of the anti-Nazi newcomers were Jewish. It’s shocking to realize that Hollywood, before the U.S. entered World War II, was still kowtowing to the German market, avoiding film subjects that would not meet with official German approval. In this era, the anti-Semitism running rampant in Deutschland also reared its ugly head on the local scene. Vicious flyers, which apparently rained down on Hollywood Blvd. from the roof of a nearby office tower, demanded, “Boycott the Movies! Hollywood is the Sodom and Gomorrah where international Jewry controls vice – dope – gambling, where young gentile girls are raped by Jewish producers, directors, casting directors, who go unpunished.” Such hideous rhetoric largely disappeared when the U.S. went to war against the Axis powers, at which time studios belatedly began grinding out agitprop movies with titles like Confessions of a Nazi Spy.

One of the most determined anti-Nazis in Hollywood was émigré Marlene Dietrich. So committed was she to broadcasting her opposition to the Nazi regime that she tried to bow out of a post-war Billy Wilder comedy called A Foreign Affair. Her role was to be that of a German café singer whose former lover was a Nazi war criminal. It apparently took great powers of persuasion to convince her that her character was not a Nazi sympathizer, but rather a cagey woman desperate for her own survival.

Survival in fact became a major concern for several in the Hollywood émigré community. Though they’d been warmly welcomed to Hollywood, they discovered another side of American life in the post-war years, when they suddenly suspected of Communist sympathies. Sadly, not a few who had proudly taken up U.S. citizenship were later hauled before the House Un-American Activities Committee. In the aftermath, they sailed back to Europe, never to return.

Published on February 06, 2015 09:42

February 3, 2015

Great Dames: Angela Lansbury and Her Peers

Not long ago, I saw Dame Angela Lansbury cavort around L.A.’s Ahmanson stage as a phony psychic in Noel Coward’s Blithe Spirit. So adorably wacky and spry was she that it was hard to accept that she’d just turned 89. One thing that British showbiz types obviously do well is longevity. Though American actresses (with the singular exception of Betty White) fret about losing roles as they approach 40, their English counterparts still get plum parts when they’re octogenarians.

This past January, Joan Collins of Dynasty fame was named by Queen Elizabeth a Dame Commander of the British Empire for her philanthropic work. Now going on 82, she’s also still performing, and still manages to look like a sex symbol. Others among Britain’s great dames are perhaps less sexy now, but they’re noted for the complexity and variety of their dramatic roles. Take Vanessa Redgrave, newly 78 and known as much for her activism as for her peerless acting chops. When she started out, she was famous for fiery political pronouncements and also for playing boldly sexual characters in everything from Blow-Up to Isadora. Today she seems rather more subdued, but her old woman roles, like that of the severe Jean du Pont in Foxcatcher, still command attention.

Maggie Smith, at 80, remains busy too, racking up awards for her imperious Duchess of Grantham in Downton Abbey. And Judi Dench, who starred along with Smith in The Best Exotic Marigold Hotel, also wears her 80 years well. Back in 1968, I remember her being described as “toothsome” when she played a seductive Titania in a filmed version of A Midsummer Night’s Dream. More recently she had a mature but hardly old-ladyish action role in the James Bond flick Skyfall, was extremely moving as a grieving mother in Philomena, and got to find screen romance (and zip around Jaipur on the back of a motorbike) in The Best Exotic Marigold Hotel. Old age doesn’t get much better than that.

Then of course there’s the ageless Lansbury. Although English-born, she got her start in American movies when barely twenty, earning Oscar nominations for her debut films, Gaslight and The Picture of Dorian Gray. She excelled at offbeat and sinister roles, most memorably as Laurence Harvey’s mother in The Manchurian Candidate. For most of her film career, she was a true L.A. person. Early on, she made ends meet by clerking at the famous Bullocks Wilshire Department Store. After fame found her, she continued to live in SoCal for many years, and I’d spot her doing her shopping at Santa Monica’s best fish store.

Since she was known as a movie actress, it was a surprise to watch her metamorphose in the late Sixties into a Broadway musical theatre star, first in Mame and then Gypsy. I saw her playing the role of Mama Rose in the latter, and will never forget the power she packed. In 1979, Stephen Sondheim and Harold Prince cast her as the thoroughly mad Mrs. Lovett, she of the infamous pie shop, in Sweeney Todd: for this role she earned her fourth Tony Award. Alas, Oscar eluded her, until she earned an honorary statuette in 2013.

Many remember Lansbury for TV’s Murder She Wrote (1984-96). One who’ll never forget her is actor Robert Forster, who told me that for this series, “She made it a habit of hiring actors who needed the work. Wow! She had a reputation for being a salvation for actors of a certain era who had slipped under the radar. So she hired me twice. She’s a real good girl.”

Published on February 03, 2015 10:30

January 30, 2015

My Lunch with Deborah Nadoolman Landis: Of Costumes and Streetwear

When the Academy Awards are handed out on February 22, the statuette for Best Costume Design will probably go to a film with bravura fantasy elements, like Maleficent or Into the Woods. But the very opinionated Deborah Nadoolman Landis suggests that each acting Oscar should be paired with a costume design Oscar. She cites the distinctive look of Javier Bardem in No Country for Old Men. Though Bardem was honored as Best Supporting Actor for that film, no one thought to acknowledge the role of the costume designer in contributing to his indelible characterization. Yet costumes instantly telegraph to the audience key information about a screen character. And the actors themselves often rely on costumes to help them prepare for their roles. As Deborah told me, “Very often they find out who they are, or who they’re going to be, in the fitting room.”

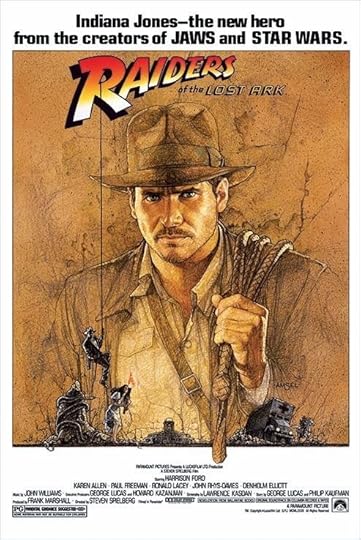

Deborah is currently riding high as the curator of the magnificent “Hollywood Costume” exhibit that wowed the crowds at London’s Victoria and Albert Museum and is now doing the same (through March 2) in Los Angeles, under the auspices of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. A costume designer herself, she came up with the iconic red jacket worn by Michael Jackson in the music video “Thriller,” directed by her husband John Landis. She was Oscar-nominated in 1989 for the Eddie Murphy comedy, Coming to America, and created the unforgettable look of Indiana Jones in 1981’s Raiders of the Lost Ark. “Hollywood Costume” contains a vivid section explaining how Indy’s leather jacket got its lived-in look: on the film set she slashed it repeatedly with a knife, after which she and Harrison Ford took turns sitting on it.

I met Deborah in 2008, while researching films of the Sixties. We talked over lunch at a Beverly Hills café, and I quickly discovered what a candid person she is. In the course of our chat, I learned a lot about her family life, her weight issues, and the fact that you’ll never get away with leaving off the pecans on her spinach salad. I also learned how much the role of the costume designer has changed since the industry was young. In Hollywood’s Golden Age, Louis B. Mayer told Helen Rose that when she was designing the wardrobe for film actors, the goal was to “just make them beautiful.” That was the era when everyone on screen was impeccably dressed and groomed, the better to delight the man and woman on the street, who couldn’t afford such luxury.

As time passed, street clothing got increasingly informal, and the designer was now expected to reflect the new reality. But it took the Hollywood studios a while to get the message. Deborah entered the industry in 1975, with a newly minted MFA in costume design from UCLA. She remembers “a tremendous disconnect between Hollywood – between the production of Hollywood – and what was actually happening on the street.” In studio costume workrooms she found “everybody was soold. . . . They were craftspeople, artisans, from Vienna and Berlin. They were all refugees. These were women who were used to making the most beautiful dresses and suits in the world. Couture. They weren’t gonna make dirty jeans or torn jeans or hippie gear. So how were they gonna cope with movies about the Summer of Love? “

What did Deborah wear at our lunch? Casual clothing that made no lasting impression at all. Far be it from her to trick herself out in an ensemble that, like an over-designed film costume, “doesn’t quite disappear the way it should.”

Published on January 30, 2015 10:00

January 27, 2015

Clothes Make the Man: the “Hollywood Costume” Exhibit

A Most Violent Year garnered critical raves. I had admired Oscar Isaac in Inside Llewyn Davis and Jessica Chastain in just about everything, so this gritty little drama about an ambitious young couple seemed worth a look. Alas, I found it grim, slow, and – frankly – rather dull. When, mercifully, the lights came up, what I remembered was the clothes. Though I’d love to have them in my own closet, I’m emphatically not tall enough and not rich enough to be worthy of the duds being sported by the film’s lead actors. Isaac, playing a Latin American immigrant who rises quickly in the New York heating oil business, circa 1981, is resplendent in an elegant camel’s hair topcoat. Chastain, as his semi-scrupulous wife, looks sleek and dangerous in vintage Armani. Kudos to costume designer Kasia Walicka-Maimone for knowing how to use clothing to delineate character.

The idea that, as Martin Scorsese puts it, “costume is the character,” is at the center of a grand exhibit called, simply, “Hollywood Costume.” It’s housed through March 2 in L.A.’s art-deco May Company Wilshire building, the future home of the long-awaited museum of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. Though an exhibit devoted to motion picture costumes seems like a natural fit for SoCal, this display got its start at London’s Victoria and Albert Museum, where fans of Hollywood flocked to see Marilyn Monroe’s Seven Year Itch sundress and Dorothy’s blue gingham pinafore. One big thing I learned from the exhibit is that Hollywood costume collectors live all over the world. Thanks to the hard work of curator Deborah Nadoolman Landis, a costume designer herself, many spectacular ensembles have been gatheredfor us to enjoy. And the handling of the exhibit – which is full of both strong ideas and Hollywood pizazz -- is definitely part of its charm.

The exhibit includes a wonderful array of queenly garments drawn from various portrayals of Elizabeth I (by Bette Davis, Judi Dench and others), as well as the austere and lovely Queen Guenevere wedding gown designed for Vanessa Redgrave in Camelot. Nor does it overlook the raincoat, boots, and headscarf worn by Elizabeth II as she mucks about Scotland’s Balmoral Castle in The Queen. The point, of course, is to outfit the actors in garments that suggest an appropriate history. The film Milk, for instance, evokes the actual T-shirt-and-khakis look of Harvey Milk’s activist years. On the other hand, there are fabulous fantasy costumes, like those designed for The Addams Family and the live-action 101 Dalmatians. In passing, I learned something wholly unexpected about Deborah L. Scott’s work on Avatar. Though that film’s most memorable sections, which take place on the planet Pandora, make heavy use of motion capture and CGI to bring us the non-human Na’vi civilization, Scott was required to fashion actual samples of exotic jewelry to adorn Avatar’s CGI creations.

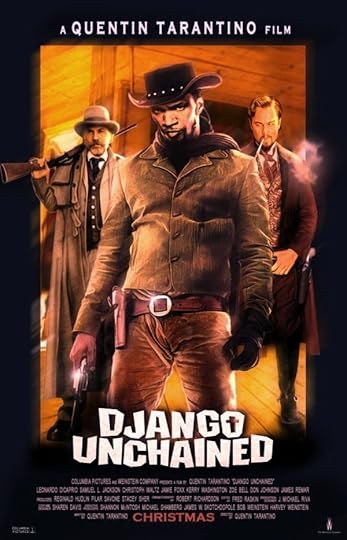

I discovered that Charlie Chaplin’s famous Little Tramp characterization first sprang to life when Chaplin began assembling existing wardrobe pieces (tight jacket, baggy pants, big shoes) and added a mustache. And a particularly enlightening section pairs successful designers with the directors who love them. There’s video of the late Mike Nichols, for instance, discussing his collaboration with Ann Roth, who chose cheap wigs and a ratty fake-fur jacket to establish Natalie Portman’s character in Closer. And Quentin Tarantino explains what he’d required of designer Sharen Davis on Django Unchained. To outfit the title character played by Jamie Foxx, he wanted a jacket and hat subliminally reflecting the wardrobe of Little Joe Cartwright (Michael Landon) on TV’s Bonanza. Who knew?

Published on January 27, 2015 12:06

Beverly in Movieland

I write twice weekly, covering topics relating to movies, moviemaking, and growing up Hollywood-adjacent. I believe that movies can change lives, and I'm always happy to hear from readers who'd like t

I write twice weekly, covering topics relating to movies, moviemaking, and growing up Hollywood-adjacent. I believe that movies can change lives, and I'm always happy to hear from readers who'd like to discuss that point.

...more

- Beverly Gray's profile

- 10 followers