Beverly Gray's Blog: Beverly in Movieland, page 110

May 8, 2015

Bruce (Jenner) Almighty-- A Hymn to Her

It’s an odd coincidence that just as Bruce Jenner was announcing to the world, via his 20/20 interview with Diane Sawyer, that he perceives himself as a woman, I was heading for the annual New York conference of the American Society of Journalists and Authors. This year’s keynote speaker was Jennifer Finney Boylan, whose memoir, She's Not There: A Life in Two Genders, was the first book by an openly transgender American to climb the bestseller lists. Because I was not familiar with Jennifer’s career, I anticipated her appearance at the conference as something of a stunt. As she herself jokes, in this day and age (following well-publicized visits to every major talk show) she’s something of a “professional transsexual.” But she’s also, I learned, a very real writer, who’s been devoted to her craft since (as James Boylan) she completed a graduate degree in English at John Hopkins University in the 1980s. She’s published novels as well as memoirs, and was a much-admired professor at Colby College from 1988 to 2014. (Here's a link to a recording of her highly emotional keynote address.)

When you become a public figure representing a social issue of the moment, your privacy is gone. Jennifer mildly gripes that these days she spends her professional life discussing her “down below” parts. Interviewers “all want to talk about my panties,” rather than her authorial skills. It can’t be avoided. Since she transitioned in 2000 at the age of 40, she’s been a rather unusual-looking woman: very tall, very thin, with a voice that doesn’t seem to belong to either gender. There are other complications: she’s been married to a woman since 1988 and has fathered two sons. Fortunately, she’s got a great sense of humor, as well as a close-knit family, and the role of an activist seems to suit her fine. As Bruce Jenner goes through his awkward post-Kardashian phase, she’ll be cheering him on.

I’ve just viewed an ABC news report on the attention-grabbing Jenner interview. Jenner, of course, moved into the spotlight at the 1976 Olympics, when he won a gold medal in the decathlon and was crowned the world’s finest athlete. Since then he’s tried to make it in Hollywood, first with such lame movies as Can’t Stop the Music (a pseudo-biopic about the Village People) and more recently on reality TV’s Keeping Up with the Kardashians. It’s doubtless challenging for him to transition while in the public eye, but at the same time he’s able to do a great deal of good for others in his predicament. One ABC newscaster mentioned that only 8% of us actually know someone who’s transgender. His colleague summed up Jenner’s contribution: “In a sense, we all know someone now.” Jenner’s fame, in other words, helps others who question their gender identity feel that they’re not alone.

Hollywood celebrities sometimes seem rather pointless in the great scheme of things. They wear great clothes; they make lots of money—so what? But because of their fame, they’re in a position to do much good in the world. Rock Hudson’s admission that he was dying of AIDS put a face on a terrible epidemic. The plight of Christopher Reeve drew attention to spinal cord injuries; Michael J. Fox made the world take heed of Parkinson’s disease. Angelina Jolie’s willing to speak openly of her double mastectomy may help save the lives of other women who, like her, are coping with a BRCA1 gene mutation that almost guarantees breast cancer. So now it’s Bruce Jenner -- superathlete, actor, honorary Kardashian -- who can use his own private woes to educate the rest of us. I wish him (or her) well.

Published on May 08, 2015 11:55

May 5, 2015

"Pretty in Pink": Dress for Success (or Excess)

Pretty in Pink, like virtually all movies written by John Hughes, is about teenagers. But it’s also fundamentally about clothing, about the transformative power of wearing what suits you best. This motif is certainly not a rare one in Hollywood. Way back in 1939, Ernst Lubitsch directed Ninotchka, a satirical look at the USSR of Stalin’s day. It features Greta Garbo as a by-the-book Soviet envoy who arrives in Paris wearing a sensible suit and a stern look on her lovely face. Fairly quickly, though, she’s seduced by the French attitude toward life, which includes romantically-inclined men and gorgeously romantic gowns. A change of clothing inevitably produces a change in attitude, which leads to the famous advertising catchline, “Garbo Laughs!” (The musical version of Ninotchka, with tunes by Cole Porter and starring Cyd Charisse in the Garbo role, is appropriately titled Silk Stockings.)

In the 1950s, a good many of Audrey Hepburn’s best romantic comedies involve the changing of clothes. Roman Holiday, from 1953, details the evolution of a princess when she flees her royal digs, ditches the white gloves, gets a pixie haircut, and tours Rome on the back of a motorbike. Sabrina(1954) shows Hepburn evolving in the opposite direction: once this chauffeur’s daughter returns from culinary school in Paris, she’s so modishly turned out that wealthy suitors come flocking. In Funny Face (1957), once photographer Fred Astaire spots her in a New York bookstore, Hepburn blossoms from a hard-core turtle-necked Bohemian into an elegant fashion model. And then of course there’s My Fair Lady (1964), in which her Eliza Doolittle learns not only to speak proper English but also to garb herself like a duchess.

Anne Hathaway’s discovery of the art of looking chic is central to the plot of The Devil Wears Prada. But when it comes to high school movies, style generally goes hand in hand with a focus on conformity. Take Grease (1978), in which the romance between Sandy and Danny is nearly thwarted because her prim good-girl clothing doesn’t jibe with his leather-jacket greaser look. When true love finally wins out, the finale is marked by Sandy’s sudden metamorphosis into a hot chick squeezed into tight pants and black leather. But the quintessential high school fashion flick is Clueless (1995), in which Cher Horowitz and her coterie at Beverly Hills High turn up their pretty noses at anyone who lacks their style savvy. A good deed for Cher is giving a drab newcomer a makeover, which of course includes a wardrobe overhaul. And Cher and her friends seem far less interested in education than in the contents of their trendy, extensive closets.

What makes Pretty in Pink distinctive is that it celebrates those high school non-conformists who write their own fashion rules. Though Andie Walsh (played by Molly Ringwald in a role written with her in mind) is unable to afford the stylish duds the rich kids wear, she also clearly takes pride in her thrift shop finds and in the outfits she’s cobbled together from odds and ends. In Pretty in Pink, an urban L.A. high school is divided between the pampered “richies” and the outcast “zoids,” who consciously elevate oddness into a fashion statement. Some, like Andie’s pal Duckie, merely look peculiar in their clashing patterns and eccentric accessories. But Andie’s sartorial experiments are born out of a true artistic sensibility that we know will ensure her a bright future. She may be mocked by her more upper-crust female classmates, but her bravery, originality, and flair also win her admiring glances—and get her the guy of her dreams.

Published on May 05, 2015 13:38

May 1, 2015

"Camelot" Ushers in the Lusty Month of May

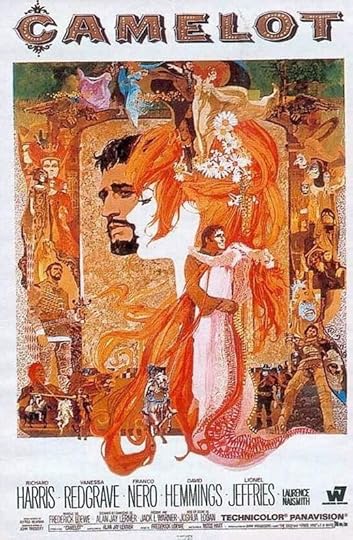

Today is May 1, the traditional date for little girls to dance around Maypoles and Soviet workers to parade through the streets. It’s also the start of “The Lusty Month of May.” This is the title of a big production number in Lerner and Loewe’s Camelot, and it’s my cue to talk about the 1967 movie version of the Broadway musical hit.

Jack Warner, the last of the great movie moguls, loved Camelot. He was convinced that a film adaptation could be as huge a box office success as the top roadshow of that era, The Sound of Music. He also felt it could equal the cachet of Warner Bros.’ previous Lerner and Loewe extravaganza, My Fair Lady. Nearing the end of a long career (he was about to sell the studio to Seven Arts), Warner anted up $1 million to buy the film rights, then spent a great deal more to make the production as sumptuous as humanly possible. Ultimately he invested somewhere in the neighborhood of $15 million, which in that era was an enormous expenditure. His crew, headed by director Joshua Logan, filmed at eight Spanish castles. Australia designer John Truscott was signed to produce exquisitely detailed costumes, like Queen Guenevere’s wedding gown. Encrusted with tiny sea shells and pumpkin seeds, it’s reported to have cost $12,000, though its full beauty was never fully captured on screen.

So intense was Warner’s focus on Camelot that he pretty much ignored smaller Warner Bros. films of that era, like Bonnie and Clyde. At first his gamble seemed like a good one. The fact that Camelot was widely known as the favorite musical of the late President Kennedy worked in his favor, and the story’s elegiac tone seemed to suit the mood of the day. So many expensive reserved seats were sold well in advance that he could afford to stock his picture with rising young British stars like Richard Harris and Vanessa Redgrave whose appeal was largely to the art-house set. Said Warner with satisfaction, upon watching the completed film, “It’s the best thing I’ve ever seen. I’m not sure that there’ll be pictures like that one any more.”

Director Logan, in talking about Camelot’s appeal, emphatically did not promote it as suitable for a family audience. The story, of course, is that of the tragic love triangle between the mythic King Arthur, his queen, and the noble knight, Sir Lancelot du Lac. Promised Logan, “The film shows real adultery in the relations of the King, Guenevere and Lancelot, something the stage musical didn’t do.” Tying his movie to the shifting morality of the Sixties, Logan called it “a mod treatment of the adultery theme,” with physical passion woven into the film’s very fabric. This determination to appeal to hip young Baby Boomers comes through loud and clear, starting with Camelot’s gorgeous poster, which features Guenevere’s wildly flowing and flower-entwined tresses, along with an almost psychedelic profusion of colors. The outdoor frolicking in several of the big musical setpieces seems cribbed from some edition of the Renaissance Pleasure Faire. Featured players Vanessa Redgrave (Guenevere) and David Hemmings (Mordred) represented Boomer touchstones due to their appearance in 1966’s Blow-Up, which combined philosophical conundrums with some of the first on-screen nudity that American youth had ever seen.

Warner Bros. was so sure of this film that merchandisers went berserk, offering up Camelot-themed nightwear, wallpaper, and stockings in “a pageant of ‘translucent’ colors, misting the legs in romantic shades from an enchanted spectrum.” Too bad the movie belly-flopped, leaving Bonnie and Clyde as the last big hit of the Jack Warner era.

Published on May 01, 2015 12:00

April 28, 2015

The Ubiquitous (and Surprisingly Introspective) Kirk Douglas

If you live in L.A., sometimes it seems as though Kirk Douglas is everywhere. I’ve heard him speak at a local synagogue, and I’ve attended plays at the Kirk Douglas Theatre, a Culver City movie palace converted into a playhouse specializing in intimate, unusual fare. He and wife Anne have made sizable donations to Children’s Hospital L.A. and have helped revamp playgrounds on schoolyards throughout the city. Today, when I went to do research at the Academy’s Margaret Herrick Library, I gained access to the collection via the Kirk Douglas Grand Staircase. Gracing the Herrick lobby was a special exhibit featuring the informal celebrity photos of Nat Dallinger. Prominently featured was a charming Dallinger image from 1950. It shows Kirk Douglas shaving his famous chin, while young son Michael (all of six) studiously tries out his own electric shaver in imitation of Dad.

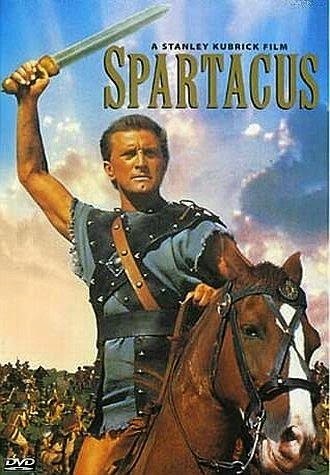

Douglas of course made the big bucks as an actor, famous for leading-man roles in films like Champion, The Bad and the Beautiful, 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea, Lust for Life, and Lonely are the Brave. But in recent years he’s become quite the writer too. There are several volumes of well-received memoir, starting with The Ragman’s Son in 1988. There’s fiction, and also books for young readers. His late-in-life exploration of spirituality produced Climbing the Mountain: My Search for Meaning, as well as several volumes about growing old. (He’s now a still-vigorous 98). But I want to discuss the book he published in 2012, I Am Spartacus!: Making a Film, Breaking the Blacklist.

The Screen Writers Guild honored Douglas in 1991 for dramatically signalling that the era of the blacklist was over. In truth, he wasn’t the first to give screen credit to a writer who’d been banished from Hollywood in the HUAC era on trumped-up charges of being a Communist. Back in 1958, producer-director Stanley Kramer hired Nedrick Young and Harold Jacob Smith to write The Defiant Ones. As Stanley Kramer’s widow Karen has often reminded me, Kramer not only put their names on the screen but also gave them roles in the film. Still, neither Young nor Smith was one of the infamous Hollywood Ten. These were prominent Hollywood screenwriters (and one director) who were sent to jail for contempt of Congress, with the approval of many Hollywood power-figures. Douglas, producing Spartacus in 1960, first concealed his hiring of the prolific Trumbo, but then had the guts to credit him for his work. He was emotionally told by Trumbo, who had recently won two screenwriting Oscars officially credited to others, “Thank you for giving me back my name.”

Douglas’s Spartacus book isn’t only about the blacklist. He tells great yarns about the casting of Jean Simmons, the hiring of a young Stanley Kubrick to replace a less accomplished director, and the heroic dedication of Woody Strode. There’s also a disturbing glimpse of Laurence Olivier’s wife Vivien Leigh, deep in the throes of bipolar disorder. As an aside, Douglas shares the story of his own son, Eric, who years later struggled with the same cruel disease.

Part of what makes this book so fascinating is its sense of an old man looking back. At one point Douglas notes, “Writing about myself almost fifty-three years ago is a strange experience. I’m learning a lot about the man I was back then; I’m not sure I like him very much.” Elsewhere he admits, “I was a very different person fifty years ago . . . . I was surprised by how headstrong I was back then, and yet that’s probably what helped me to make Spartacus.”

Published on April 28, 2015 10:00

April 24, 2015

Ethel Payne Visits the House of Bamboo

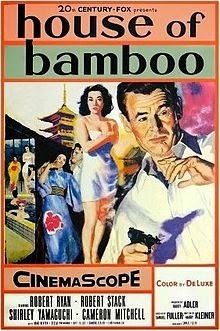

Tough-guy director Sam Fuller was at the helm of House of Bamboo, the first Cinemascope film ever shot in Japan. The year was 1955, when the American military occupation of post-World War II Japan was still very much in evidence. In fact, House of Bamboo gives prominent screen credit to the Military Police of the U.S. Army Forces Far East, the Eighth Army, the Government of Japan, and the Tokyo Metropolitan Police Department for facilitating the film's production.

This means, of course, that both the occupying U.S. Army and the Japanese forces of law and order are seen on screen in a wholly positive light. The bad guys are all American: a crime ring led by Robert Ryan, who rides herd over a bunch of dishonorably discharged GI’s. The number-one good guy is American too. He’s played by Robert Stack, who goes undercover to quash Ryan and his henchmen. But then there’s the inevitable “kimono girl,” played by the era’s favorite Japanese singer and actress, Shirley Yamaguchi. She was born Yoshiko Yamaguchi in Manchuria to Japanese parents. Early in her career, she played Chinese characters in Japanese propaganda films. After the war, she starred in both Japanese and English-language movies, and later served for eighteen years in Japan’s Parliament. She passed away last year at age 94. (My Japanese-American hairdresser was named after Shirley Yamaguchi by her father, who was a serious fan.)

In House of Bamboo, Shirley Yamaguchi’s character is that of a gentle but brave young Japanese woman who has made the mistake of marrying one of the American thugs. His death kicks off the film. Later, after being thrown together with Robert Stack, she displays great courage in supporting his efforts to bring the gang to justice. It’s predictable: she’s loving, domestic, and always submissive, entirely in keeping with the stereotypes of the era. In movies, at least, those sweet, docile Japanese women couldn’t seem to get enough of western men.

I thought of House of Bamboo when reading James McGrath Morris’s fine biography of the pioneering African-American journalist Ethel Payne, whose coverage of the civil rights era helped shape American history. In 1948, as a young woman not yet bent on a journalism career, Payne shipped out to Tokyo to work with black servicemen through the USO. She was surprised to find young Japanese women being drawn to African-American soldiers. The attractiveness of Americans was obvious: in an era of deprivation they had ready cash and access to western goods. And Payne discovered that many Japanese women preferred black soldiers, whom they found kinder and more generous than their white counterparts.

Payne soon spoke to visiting African-American journalists about the attraction between black GI’s and what they called musumes (adapting the Japanese word for young lady). The musume, she noted, “fetches the GI’s shoes, washes, cooks, and irons. Keeps quiet, when asked. Never talks back. Laughs easily. All of which is very soothing to the male ego.” Payne displayed some skepticism about these women’s long-term motives: “Musume has played it cool. Her very helplessness has been a powerful weapon and an asset to her and she is using it fully.” Such observations ended up informing Payne’s own first bylined article in the Chicago Defender, which was topped by the headline “Says Japanese Girls Playing GIs For Suckers, ‘Chocolate Joe’ Used, Amused, Confused.”

“Chocolate Joe” may have been used, but others suffered far more. Payne visited orphanages full of mixed-race babies, abandoned by their mothers. Those who were half-black bore the brunt of two nations’ rejection. It occurs to me that there’s surely a movie in that.

Biographer James McGrath Morris, author of Eye on the Struggle: Ethel Payne, the First Lady of the Black Press, will be a featured speaker at the sixth annual conference of BIO, the Biographers International Organization, on June 5-6, 2015, in Washington, D.C. The public is most welcome!

And here's more on Ethel Payne.

Published on April 24, 2015 10:09

April 21, 2015

Robert Forster’s Movieland ABCs: A is for "Alligator"

Robert Forster has co-starred in films directed by John Huston (Reflections in a Golden Eye), Robert Mulligan (The Stalking Moon), David Lynch (Mulholland Drive), and Alexander Payne (The Descendants). He was the top name in Oscar-winning cinematographer Haskell Wexler’s landmark feature film debut, Medium Cool. For Quentin Tarantino’s Jackie Brown, Forster nabbed an Oscar nomination as best supporting actor. So what film does he remember most fondly? Forster told me, over breakfast last December, that “Alligator is as good a picture as I have in my career.”

Alligator, directed in 1980 by Roger Corman alumnus Lewis Teague, has many familiar Corman components. There are car crashes, explosions, wry humor, and (oh yes) a large, scary alligator that bares its fangs and reduces people to a bloody pulp. The film’s screenwriter, now a respected indie filmmaker, also got his start at Corman’s New World Pictures. Of course I mean John Sayles, who was discovered by my good friend Frances Doel when he was publishing short stories in Esquire. This was the era when Jaws, the biggest hit movie around, was called “a Roger Corman movie on a big budget.” Roger being Roger, he wanted to capitalize on Jaws’box office success. But for Roger’s cheapie sensibilities, a movie about a giant scary fish was too expensive to contemplate. That’s why he put his money (all $600,000 of it) into a movie about small scary fish. He asked Frances, his ace assistant, to find a promising screenwriter, and she came up with Sayles. In-house Corman editor Joe Dante was drafted to direct, and the result was Piranha, a potent combination of horror and humor, scares and laughs.

Alligator, shot two years later, has more of the same, though it was not made on Corman’s dime. As a Jaws spoof it got extremely strong reviews: the New York Times chose it as one of the summer’s three best movies. And it did especially well on television. For Forster it proved to be “the only movie in my entire career I got paid a back end.” In civilian speak, this means that ABC-TV (which bought and then did a great job of publicizing the film) earned enough on it that Robert was entitled by contract to reap some of the profits. As every actor in Hollywood knows, a profit participation pay-off is something that’s hugely coveted, but only rarely collected.

Forster’s affection for Alligator is not purely mercenary, though. As an actor who enjoys playing good guys, he’s fond of his character, a down-and-out police detective whose partners keep meeting a bad end. Despite the workplace trauma with which he grapples, he’s capable of wit and humor, though not about his thinning hair. (According to Sayles, it was Forster who suggested that his personal struggle with male pattern baldness be used as a running gag.) Sayles’ trademark social commentary makes an appearance, as do some of Hollywood’s best character actors: Michael Gazzo, Dean Jagger, Jack Carter, and Sydney Lassick (someone I’d worked with decades before he was featured as Cheswick in One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest). There’s a budding love relationship with a pretty herpetologist played by Robin Riker (later to star in Corman’s Stepmonster). And there are some genuinely scary moments, like the alligator exploding out of a manhole to terrorize pedestrians.

One of my favorite characters, aside from Forster’s David, is a self-styled Great White Hunter (Henry Silva) who treats local ghetto kids like native bearers as he stalks his prey—with predictably tragicomic results. No wonder Stephen King once told Forster at Cannes that Alligator was his favorite horror film.

Published on April 21, 2015 11:41

April 17, 2015

Edward Herrmann Responds to a Casting Call

On the most recent documentary produced by Ken Burns, the mellifluous voice of Edward Herrmann is very much in evidence. He serves as narrator of Cancer: The Emperor of All Maladies , a six-hour PBS special based on Siddhartha Mukherjee’s book. This was hardly Herrmann’s first gig for Ken Burns: he had previously voiced the words of FDR on Burns’ The Roosevelts: An Intimate History. Sadly, Cancer: The Emperor of All Maladies was Edward Herrmann’s last opportunity to speak into a microphone. He recorded his narration while suffering from brain cancer, to which he succumbed, at the age of 71, on the last day of 2014.

Edward Herrmann will always be linked to FDR in my mind. I first became aware of him back in 1976, when he starred with Jane Alexander on a much-admired TV miniseries, Eleanor and Franklin. Since that time, he’s played such historic figures as Lou Gehrig, George Bernard Shaw, Max Eastman (in Reds), Andrew Carnegie, Nelson Rockefeller (in Nixon) and William Randolph Hearst (The Cat’s Meow). There’s something about Herrmann’s patrician style that seems to link him to the history books. But he’s also appeared on TV as Herman Munster, and from 2000 to 2007 won fans as Lorelai’s amusingly pompous dad on Gilmore Girls.

Yet there was a time when Edward Herrmann, future portrayer of presidents and potentates, was a struggling actor trying to make inroads in Hollywood. While he was performing with the Dallas Theater Center, he submitted his credentials and headshot to an L.A. production company in hopes of being considered for the young male lead in an upcoming film. Its title? The Graduate. Needless to say, he didn’t get the part. Nor did Harvey Keitel, nor John Glover, nor Richard Egan, nor Frederic Forrest, all of whom were nobodies in 1967, but went on to have substantial Hollywood careers. Nor did lots of eager young amateurs who responded to newspaper items about a nationwide talent search.

A casting maven like The Graduate’s Lynn Stalmaster has one of the world’s most heartbreaking jobs. He or she must see many, many actors—all desperate for work—and choose only one. Of course, the producer and director weigh in too, and (in television) sometimes the writer as well. Richard Hatem captures the agony of the casting process from a writer’s perspective. To start with, “There is nothing—nothing—like the first day of auditions. It’s a day you will remember for the rest of your life. Real live actors, several of whom you recognize from other shows you love and hate, are walking into this small, poorly lit room. And they nervously introduce themselves to you, and they compliment you and tell you how much they love your script, and they begin speaking the lines that you wrote. It is infatuating and intoxicating. You have never felt more honored. Or important.”

Then “by the third day, the fun is over. You have heard your lines read one hundred times, and by now, they all sound terrible and dull and unfunny. . . . You thought sitting in judgment of others would finally allow you the opportunity to assess others fairly and generously, in the way you always wished others would assess you and your work. And now, you realize what a fool you were, because there is no way to judge these actors fairly. It is physically impossible for you to hear your lines with the same degree of enthusiasm and bigheartedness on day three as you did on day one.”

Somehow Edward Herrmann made it through this onerous process. May he rest in peace.

Published on April 17, 2015 08:59

April 14, 2015

Bhopal: A Prayer for Rain – Trying to Save One Corner of the World

As the world lurches from crisis to crisis, we tend to forget what happened in Bhopal, India on December 3, 1984. The explosion at a Union Carbide pesticide plant that released clouds of dangerous chemicals into the air quickly killed some ten thousand locals. It also launched a health crisis that continues to this day, as mothers genetically affected by the blast give birth to severely damaged children. Bhopal was, in fact, the worst industrial accident of all time. And there’s no end in sight.

Lest we forget, Indian pediatrician-turned-filmmaker Ravi Kumar has co-written and directed Bhopal: A Prayer for Rain, a 2014 independent feature that spells out the events leading up to the tragedy as well as its cost in terms of human lives. Bhopal: A Prayer for Rain was screened last week for the press and budding Hollywood activists as part of Kat Kramer’s seventh annual Films that Change the World series. Featured guests included the very eloquent Tim Edwards, an Englishman who’s become the executive trustee of the Bhopal Medical Appeal. Edwards reminded his listeners that Bhopal, where thirty tons of poisonous gas spilled out into a densely populated slum area five miles square, was “a disaster with a beginning but no end.” In the absence of true leadership from the government of India and from Union Carbide (which has shrugged off all claims of responsibility), Edwards’ group has dedicated itself to founding medical clinics for those still suffering from what he likens to “chemical AIDS.” Bhopal: A Prayer for Rain, in dramatically depicting the scope of the crisis, should encourage people of good conscience to support these fund-raising efforts. (Live-streaming of this event throughout the globe is one way in which current technology is helping to spread the word.)

One stand-out in this film is its cinematography, capturing the color of daily life in a small Indian city, and then presenting in excruciating detail the full sweep of the death and destruction. The original plan was to focus chiefly on an actual crusading journalist (portrayed by Kal Penn) who—aware of sloppy safety practices at the Union Carbide plant—predicted the disaster to come. But someone wisely recognized that this story belonged chiefly to the victims. A wonderfully likable Indian actor named Rajpal Yadav becomes the everyman figure whose determination to support his family puts him in the thick of the Union Carbide operation, which was intended to bring to an impoverished community much-needed jobs.

Yadav’s character is an innocent, but there is plenty of blame to go around. The Indian plant managers are portrayed as so oblivious to basic safety precautions that they shut off the essential cooling systems to save money. Then there’s the big boss of Union Carbide. As portrayed by Martin Sheen (who’s legendary in Hollywood for taking on major social issues), he’s an affable chap, one who genuinely wants the best for Indian workers—but will always put the needs of his company first. (This balanced portrait of the late Warren Anderson, who was personally devastated by what his factory had wrought, is apparently quite accurate.)

As Stanley Kramer’s daughter, Kat Kramer works hard to bring a progressive social consciousness to these events. That’s why this year she inaugurated an award honoring actress and social activist Marsha Hunt, who was present in all her nonagenarian glory. The still-elegant Hunt spoke movingly: “To be thanked for what gave me so much joy in my life is kind of crazy.” But I noticed that much of the evening’s press coverage went to the film’s co-star, Mischa Barton, for her plunging neckline. Ah, Hollywood!

Published on April 14, 2015 11:59

April 10, 2015

Stan Freberg Discovers America

The voice is solemn, stentorian, coming from deep within the lower register: “STAN FREBERG MODESTLY PRESENTS THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA.” Then there’s a jaunty overture, after which Christopher Columbus stops playing hanky-panky with Queen Isabella long enough to hit up the Spanish treasury for three ships on which to sail off into the unknown. Next thing we know, a gaggle of sailors are bound for Miami Beach, harmonizing on “It’s a Round Round World.” It’s all part of Columbus’s grand dream to open the first Italian restaurant in America: “Starches, cholesterol, all the finer things.” And so it goes.

Stan Freberg, who died this week at 88, was successful in many venues. As a voice actor, he played Cecil the Seasick Sea Serpent on the classic kids’ TV show, Time for Beany, then voiced roles in Bugs Bunny cartoons and in Disney’s Lady and the Tramp. His parody recordings, like the Dragnet spoof “St. George and the Dragonet,” sold millions of copies. When he moved into advertising, he brought his goofy sense of humor with him. Sunsweet sold a lot of pitted prunes after he announced in radio and TV spots that the company was dedicated to futuristic breakthroughs: “Today the pits, tomorrow the wrinkles.” Peddling Chung King chow mein, he added handles to the cans, so that consumers could feel as though they were getting takeout from their favorite Chinese restaurant.

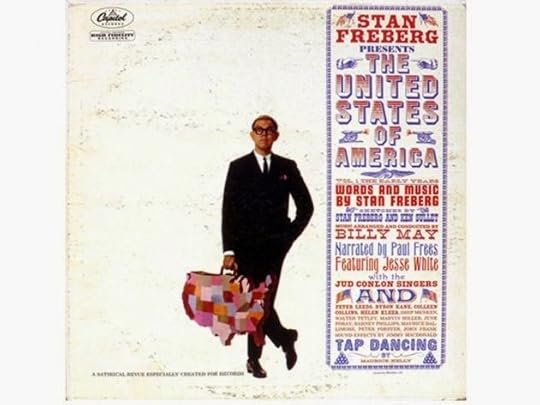

But true Freberg enthusiasts best remember his long-playing 1961 album, Stan Freberg Presents the United States of America,Volume One:The Early Years . This was a full-blown musical production with a cast of, well, dozens, and an orchestra conducted by Billy May. (As fans will recall, there was tap-dancing too.) The songs, gags, and verbal tics proved so infectious that my family quickly had the entire album by heart. During my college years, my social life revolved around finding fellow Freberg addicts who, like me, could rattle off Betsy Ross’s gripe to George Washington: “Hey,you’re tracking snow all over my Early American rug!”

Since Freberg’s death, commentators have noted the way he danced along the edge of the day’s key social issues. They often mention the skit in which Benjamin Franklin resists Thomas Jefferson’s arm-twisting over the signing of the Declaration of Independence. Sings Tom, “You’re so skittish . . . who possibly could care if you do?” Ben answers: “The Un-British Activities Committee, that’s who.” But my personal favorite\, involving the first Thanksgiving, pokes fun at the era’s commitment to token measures on behalf of civil rights. It seems that a Puritan mayor, in a tough re-election battle, is being urged by his campaign staff to reach out to the underclass.The idea: “Take an Indian to lunch . . . this week/ Show him we’re a regular bunch . . . this week/ Show him we’re as liberal as can be./ Let him know he’s almost as good as we.” After all, says the mayor, “We came over on the Mayflower.”

There’s lots more silliness too. Like George Washington, preparing to cross the Delaware, dithering about which boat he should rent. And Peter Tishman (aka Minuit) being fleeced on the deal to buy Manhattan for 23 dollars worth of junk jewelry (“You thought you bought a furnished island?”). Naturally, the disrespect shown to the Founding Fathers raised some hackles. (An outraged Daughter of the American Revolution shows up for a cameo at album’s end.)

Decades later, I was introduced to Stan Freberg. I wanted to make a clever allusion to this album, but nothing came out of my mouth. Which he must have found very funny indeed.

Published on April 10, 2015 10:58

April 7, 2015

Frank Sinatra: Singing in Many Keys

These days, action fans are thrilling to the new seventh installment of the Fast and the Furious franchise. Me? I’m thinking about Frank Sinatra.

It’s fair to say that Old Blue Eyes always found himself where the action was. Starting out as a big-band singer with Harry James and Tommy Dorsey, he quickly became a teen idol, then matured into an incomparable lounge singer, balladeer, and “poet of loneliness.” His personal life was colorful, to say the least, full of romantic escapades and marriages to such disparate dames as Ava Gardner and the very young Mia Farrow. There were the friendships with leading politicians, the rumors of mob involvement, and the Las Vegas hijinks involving his buddies in the so-called Rat Pack.

All of this gives plenty of material to Alex Gibney, the celebrated documentary filmmaker best known for such politically charged work as Enron: The Smartest Guys in the Room, Client 9: The Rise and Fall of Eliot Spitzer, and the Oscar-winning Taxi to the Dark Side. Just last week, Gibney attracted a record-breaking 1.7 million viewers to HBO when the network premiered his Going Clear: Scientology and the Prison of Belief. The Scientology story has its Hollywood side, and Gibney has long revealed his musical interests in documentaries about Jimi Hendrix and James Brown. So it’s perhaps not surprising that (in honor of the one-hundreth anniversary of the singer’s birth) he’s produced a two-part HBO special, Sinatra: All or Nothing at All. So far I’ve only seen Part One, but look forward to more. Personally, I love Sinatra’s voice and his way with a lyric, but for now I want to concentrate on something more suprising: his highly successful movie career.

Yes, Sinatra made more than fifty movies. The first batch consisted of lightweight musical fare, though such films as Anchors Aweigh and Take Me Out to the Ballgame were far more sophisticated then any of the Elvis Presley showcases a decade later. After all, Frank was up there on the big screen tap-dancing with the great Gene Kelly and engaging in comic repartee with spunky Betty Garrett. One of my all-time favorites is 1949’s On the Town, in which three sailors (Sinatra, Kelly, and the goofy Jules Munshin) on shoreleave in New York City sing Leonard Bernstein songs, trade Comden-and-Green quips, and woo the delightful Garrett, adorable Vera Ellen, and sexy Ann Miller atop the Empire State Building. Four years later, Sinatra won a key dramatic role in the film made from James Jones’ bestselling From Here to Eternity. The part of the feisty and ultimately tragic Maggio, which at first was intended for Eli Wallach, won Sinatra a well-deserved supporting actor Oscar. Soon thereafter, he earned a best actor nomination for his intense portrayal of a drug addict in The Man with the Golden Arm.

Having earned his stripes as a dramatic actor, Sinatra continued to take the occasional light comedy role, like that of the swinging bachelor in The Tender Trap. I also remember him as the original Danny Ocean, and as the star of a low-key little love story called A Hole in the Head, opposite Eleanor Parker. But he never stopped being ambitious: how could anyone forget The Manchurian Candidate? Shirley Jones, an actress known for being forthright, has recounted how in 1956 Sinatra was supposed to be her leading man in the film adaptation of Rodgers and Hammerstein’s Carousel. At the last possible moment, he dropped out, and she’s convinced he was daunted by the role’s complex musical and dramatic challenges. Maybe so, but I doubt he was ever scared again.

Published on April 07, 2015 13:27

Beverly in Movieland

I write twice weekly, covering topics relating to movies, moviemaking, and growing up Hollywood-adjacent. I believe that movies can change lives, and I'm always happy to hear from readers who'd like t

I write twice weekly, covering topics relating to movies, moviemaking, and growing up Hollywood-adjacent. I believe that movies can change lives, and I'm always happy to hear from readers who'd like to discuss that point.

...more

- Beverly Gray's profile

- 10 followers