Beverly Gray's Blog: Beverly in Movieland, page 107

August 21, 2015

Bud Yorkin: Engineering a Showbiz Career

Of course I’m dating myself, but I remember the 1971 TV debut of All in the Family. I was a grad student, hanging out with my boyfriend at the UCLA Department of Meteorology, where he had a part-time job. We both had work to do, but the show was getting so much advance press that it seemed obligatory to check it out. So we watched it on a little black-&-white TV in someone’s office. Black-&-white seemed appropriate for a show that was intended to raise hackles via the views of a lovable bigot. Frankly, we didn’t know what to think.

All in the Family was inspired by a frank but funny British sitcom, “Till Death Us Do Part.” But it was all-American in its focus on the cultural conversation of its time. Over nine years, it tackled issues pertaining to race, religion, gender, and class, deliberately courting controversy. Before its long run was over, it had sparked such spin-offs as Maude, The Jeffersons, and Sanford and Son. Credit for the show’s long-term success is usually given to Norman Lear, but his producing partner, Bud Yorkin was the one who started the ball rolling. Lear himself said it: “He was the horse we rode in on, and I couldn’t love or appreciate him more.”

I knew that Yorkin, who died this week at the age of 89, had made many contributions to TV and film comedy. Aside from his producer credits, he directed amiable films like 1963’s Come Blow Your Horn and 1967’s Divorce, American Style, then won Emmys for his stylish handling of one of TV’s seminal variety shows, An Evening with Fred Astaire. What I didn’t know until I read the obits was that Yorkin had an engineering background. After spending World War II in the Air Force, helping to install sonar systems in the Pacific, he earned an electrical engineering degree at Carnegie Tech, and his first stab at an entertainment job was a stint repairing TV sets.

I’m delighted by Yorkin’s engineering credentials because, though his route to Hollywood is not the usual one, he is not totally unique. My legendary former boss, B-movie maven Roger Corman, decided to break into showbiz after graduating from Stanford with a degree in industrial engineering. Many Cormanites have commented to me on how the engineer’s zest for problem-solving has shaped Roger’s filmmaking career: “He’s always written movies in three days, shot them in three days, used the same sets to shoot two or three movies. He loves that because that’s the efficient engineer in him. He loves that sense of being practical. You’ve had the expense of building the set, making the monster, now let’s get as much as we possibly can out of it.” One Corman veteran theorizes that “one of his great joys in life is to come into total chaos and to straighten it out. And I think this has something to do with his engineering background. I sometimes think Roger actually, on some levels, creates problems so that he can solve them.”

Of course, filmmaking is a creative business as well as a practical one, and what this Corman alumnus calls “a very formal, black-and-white, engineering approach” doesn’t make for great art. But sometimes engineers can surprise you. I knew of one aerospace engineer, Todd W. Langen, who became obsessed with screenwriting. He took courses, studied produced scripts, and worked out a careful formula for what a good action movie should contain. Then he quit his day job. I thought he was crazy—until he resurfaced as an award-winner for The Wonder Years.

This post is dedicated to the most important engineer in my life, on our special day.

Published on August 21, 2015 10:21

August 18, 2015

The Diary of a Teenage Girl: Not Your Mother's (or Your Father’s) Sexcapades

The Diary of a Teenage Girl is not an easy movie to love. I knew going in that it would deal frankly with youthful sexuality and the violation of common social taboos. Since my focus lately has been on Mike Nichols’ bold but often hilarious cinematic explorations of sex, I figured I was prepared for anything. But, make no mistake, Diary of a Teenage Girl is no sexy romp. This despite the fact that the film, based on Phoebe Gloeckner’s ground-breaking graphic novel, finds very funny excuses to integrate animation into its cinematography, as a way of entering both its heroine’s head and her highly charged libido.

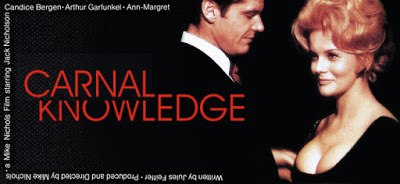

Mike Nichols, of course, tickled Baby Boomers by laying bare the bedroom adventures of Benjamin Braddock in The Graduate. He delved far deeper in Carnal Knowledge, which begins with two young collegians (Jack Nicholson and Art Garfunkel) lamenting their virginity, then follows them from innocence to impotence, with many sordid stops along the way. Carnal Knowledge is hardly a comfortable film, but I suspect it’s one with which some male viewers will not be able to help identifying. It’s quickly clear that all the women who float in and out of Jonathan and Sandy’s lives are just vessels for their unrequited longings for – what exactly? Unconditional love? Total erotic pleasure? Novelty? In any case, in its point of view this is a guymovie, from start to finish.

A much different perspective can be seen in An Education, the 2009 British film based on Lynn Barber’s autobiographical magazine piece. This film, which introduced me to the charms of Carey Mulligan, concentrates on a smart but restless high school girl, circa 1961, who is lured into an affair with an attractive older man (Peter Sarsgaard). Though sex (on a romantic weekend in Paris) is part of Jenny’s bargain with the devil, the film’s concerns are less with her budding sexuality than with her reckless determination to escape from the middle-class values of her good-hearted but dull parents. Writer Nick Hornby, who adapted Barber’s story for the screen, said as much when he explained what appealed to him about this assignment: “She's a suburban girl who's frightened that she's going to get cut out of everything good that happens in the city. That, to me, is a big story in popular culture. It's the story of pretty much every rock 'n' roll band."

Which brings me back to The Diary of a Teenage Girl. We’re in San Francisco, in the year 1976. Fifteen-year old Minnie Goetz (bravely played by Bel Powley) has just discovered that her mother’s attractive yet feckless boyfriend Monroe (Alexander Sarsgård) is checking out her breasts. This gives her the courage to make her own interest in a physical relationship crystal-clear. And so they do. The film’s opening line is voiceover narration: Minnie’s awestruck “I had sex today! Holy shit!” But we don’t simply overhear Minnie singing the body electric. In the course of this movie we see a great deal. Soon Minnie is busily experimenting, both with Monroe and with the teenage boys who suddenly seem quite interested in her maturing self. Eventually there is very public fellatio, a threesome, and psychedelics. It all seems related to a grim San Francisco social scene I’m glad wasn’t part of my upbringing. But at least some of the reason for Minnie’s sexual urgency can be laid at the door of her mother (Kristin Wiig), who’s too busy looking for her own satisfaction to see -- until late in the game -- what her daughter has become. Then, thankfully, there’s a glimmer of hope.

Published on August 18, 2015 14:12

August 14, 2015

Theodore Bikel: A Mensch for All Seasons

Was there anything Theodore Bikel couldn’t do? In the course of a long career that ended with his death last month at age 91, Bikel showed the world that he could act up a storm, sing like a bird, and serve as an outspoken champion of human rights. He had stamina too. A friend of mine, a personal trainer, worked with Bikel for 13 years. Though fighting off several forms of cancer, including leukemia, he exercised three times a week until recently. Even when his body was finally letting go, his mind remained sharp until the end.

Bikel was by no means shy about his gifts. A strong sense of self was important for one forced to leave his beloved Vienna at the age of fourteen, one step ahead of the Nazis. His family, active in Zionist circles, relocated to pre-statehood Israel, where he first discovered acting. Soon after, he switched from Hebrew to English, playing the all-American sad sack, Mitch, opposite Vivien Leigh’s Blanche DuBois, in the London premiere of A Streetcar Named Desire, directed by Laurence Olivier.

Bikel’s facility for languages and accents came in handy when he landed in Hollywood. One of his early roles was that of a Dutch doctor living in Nova Scotia in a charming family film my parents adored, The Little Kidnappers (1953). Naturally he played German-speakers, as in The African Queen (1951), but he also gravitated toward Slavic parts, like the submarine commander in one of my own favorites, The Russians Are Coming, the Russians Are Coming (1966). In its recent obit, the New York Times enumerated some of his many linguistic incarnations: “On television Mr. Bikel played an Armenian merchant on Ironside, a Polish professor on Charlie’s Angels, an American professor on The Paper Chase, a Bulgarian villain on Falcon Crest, the Russian adoptive father of a Klingon on Star Trek: The Next Generation, and an Italian opera star on Murder, She Wrote. He also played a Greek peanut vendor, a blind Portuguese cobbler, a prison guard on Devil’s Island, a mad bomber, a South African Boer, a sinister Chinese gangster, and Henry A. Kissinger.”

His most honored role, though, came courtesy of Stanley Kramer’s love for unlikely casting. In Kramer’s landmark 1958 film, The Defiant Ones, Bikel was a Southern sheriff leading a posse to re-capture the escaped cons played by Sidney Poitier and Tony Curtis. It’s a surprisingly sympathetic part: this particular Southern sheriff is at base a humane man. The character reflects Bikel’s own strong social convictions, but as a born-and-bred Southerner he’s hard to buy. Still, audiences responded to Bikel’s portrayal, and he was rewarded with an Oscar nomination as Best Supporting Actor.

Personally, I’d rather remember him as the larcenous linguist Zoltan Kaparthy in the film version of My Fair Lady. Or as an exemplary Teyve in Fiddler on the Roof, a part he played on stage more than 2000 times.

It shouldn’t be forgotten that Bikel was also known the world over as a folk singer, one who accompanied himself on a host of instruments, including guitar, mandolin, balalaika, and harmonica. With Pete Seeger and others, he helped found the famous Newport Folk Festival in 1959. On Broadway, he created the role of Captain von Trapp to Mary Martin’s Maria in The Sound of Music. It’s said that Oscar Hammerstein and Richard Rodgers wrote “Edelweiss” especially for him. The tune’s sweet simplicity and Bikel’s mellow voice: what a perfect blending of singer and song! It well befits a man who lost his homeland, then gained the whole world.

As Capt. von Trapp on Broadway

As Capt. von Trapp on Broadway

Published on August 14, 2015 09:14

August 11, 2015

The Mystic Art of Casting

Faye Dunaway, long before Bonnie and Clyde, couldn’t get past Arthur Penn’s casting director, who said she “didn’t have the face for movies.” Casting experts, it seems, are sometimes wrong . . . and sometimes more than a little blunt. But it’s all in the line of duty. What drives casting directors is the need to find the perfect actor for each and every role.

To an outsider, being a casting director (please don’t call them casting agents!) sounds like fun. You sit in a room, while attractive people cycle through, each one aiming to please. They read the lines, you thank them politely, and jot down some yay-or-nay notes when they walk out the door. In fact, it’s extraordinarily wearying to hear the same words over and over, while trying to maintain your objectivity in the face of so much barely-concealed desperation.

Of course, casting has its amusing moments, along with its weird ones. When I worked for Roger Corman at Concorde-New Horizons, I could always tell at a glance which film we were casting. As I entered our tiny lobby, it would be full of buttoned-down businessmen, or homey grandmas, or girls who were no better than they should be. All of them were actors, of course, and they knew enough to dress the part when they showed up to audition. Once, walking up the street near the Concorde offices, I spotted a young punk sitting in his car, busily adorning himself with chains and leather. For a second I was puzzled, until I realized that we must be casting biker-types that day.

Sometimes producers and directors of studio films announce that they’re seeking a young unknown for an important part. I’m not sure how much of that is publicity gimmickry, but I do know what happened in 1967 when articles appeared across the nation saying that the makers of a small film called The Graduate were seeking a college-age young actor. Résumés and headshots flooded in, both from low-level young professionals (Harvey Keitel and the late Edward Herrmann among them) and from young men whose only qualification was a high opinion of themselves. Some sent in lengthy hand-written analyses of the Benjamin Braddock character; some indulged in rants about the way life was treating them; some let it be known that anyone failing to cast them was making a big mistake. Hoping to trade on their college experience, some enclosed graduation photos or wrote on fraternity stationery. Proud parents recommended their suitably mixed-up sons. One hopeful, with no professional photo at his disposal, scotch-taped snapshots of himself on a piece of notebook paper and sent it along. Another included in his cover-letter the following recommendation: “Previous acting experience--none, however my quality of personality is above average.”

Remarkably, all these applicants were treated with courtesy. All eventually got polite kiss-off letters explaining that the role they sought had already been cast, but that their information would be kept on file just in case.

Of course the part of Benjamin Braddock went to a professional actor, one wholly unknown in Hollywood but busily earning respect on the Off-Broadway stage. Yet sometimes a casting director achieves a real coup. Casting veteran Jane Jenkins remembers, when she was working on Mystic Pizza, how a nineteen-year-old actress showed up late in the day, badly dressed and unfamiliar with the script. Jenkins, spotting potential, urged the girl to return the following morning, dressed appropriately for the role. Overnight, Julia Roberts studied up, and traded in her baggy jeans for the sexy miniskirt the part demanded. The rest, of course, is history.

Published on August 11, 2015 12:19

August 7, 2015

Korean Wedding Guests: Put a Ringer on It

Jon Stewart just said his goodbyes. Donald Trump and his fellow Republicans – all sixteen of them -- just crowded the stage for their first debate. There’s blood in the streets at home and abroad. So why am I thinking about weddings in South Korea?

Well, everybody loves weddings, especially those who stand to profit from them financially: caterers, florists, musicians, wedding guests. Huh? Wedding guests? Well, apparently in South Korea huge weddings are all the rage. The one time I visited Seoul, back in the Sixties, middle-class families didn’t even own what we Americans would consider basic household necessities. In a Korean kitchen, instead of a refrigerator, you’d see a giant ceramic jar filled with kimchee: that’s how you’d have (pickled) vegetables to eat in wintertime. How times have changed! Thanks to a tech boom, the Korean economy is soaring. And conspicuous consumption is now the name of the game.

If you’re throwing a lavish wedding with all the trimmings, the last thing you want to see is empty seats at the ceremony and around the banquet tables. Fortunately, some creative Korean business types have stepped in to fill the void. There are agencies that, for a fee, will provide you with professional guests, guaranteed to exude good cheer and good manners. Presumably they will not get slammed at the open bar, make fools of themselves on the dance floor, start fights with members of the wedding party, or otherwise make a scene. We’ve surely known movie comedies in which all of the above happens (and maybe experienced it in real life too.). But count on Korea’s guests-for-hire to emulate our better selves.

The Korean guests know how to behave because they’re professional actors, adept at meeting the requirements of a role. Their agencies book them into back-to-back weddings, especially during the summer months, but they have other, more lucrative gigs as well. They’ve been known, in sticky situations, to impersonate a boss or a visiting relative. If someone is applying for a bank loan, they can stand in for a missing spouse.

I think we Americans are losing out on a good thing. Actors always need work, and there are times we could all surely use additional charming guests at our parties and loyal sidekicks in our entourage. There are more specialized needs too. For instance, single guys looking to curry favor with sympathetic family-oriented women would benefit from having an adorable kid or two in tow. Why not rent? (Yes, I too see the dangers of this option. But let my fertile imagination take me where it will!)

Though South Koreans are paving the way, it’s true that Hollywood—fittingly—has always enjoyed depicting weddings that are not quite for real. In the wake of such movies as The Wedding Singer (1998) and The Wedding Planner (2001), this year we’ve had The Wedding Ringer (2015), about a guy who rents himself out to social nerds to pose as their life-of-the-party best man. Most underemployed (and who isn’t?) actors would consider this a dream gig.

Of course there’s a time-honored tradition of hiring a claque to cheer your performance, whether you’re appearing in a play or a political debate. Yes, politicians, all of whom are actors in their own right, sometimes need to manufacture an enthusiastic crowd. Let’s take this one step further: if there are fake crowds, why not fake politicians, who are in fact actors hired to fill a particular ideological slot? Give them a few position papers, toss in a few snappy lines, and watch what happens. Hmmmm, maybe this explains Donald Trump.

Published on August 07, 2015 11:41

August 4, 2015

Honey, I Shrunk the Hero, or Mission: Infinitesimal

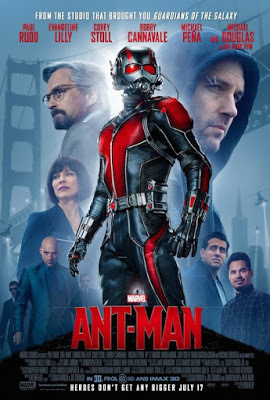

Sometimes in mid-summer I have a desperate need to see a lightweight popcorn movie. Ant-Mancertainly qualifies. It features, along with such likable actors as Paul Rudd, Michael Douglas, and Bobby Cannavale, a goofy story about yet another threat to mankind as we know it. The trailers leading up to this film contain plenty of those: it’s clear that this autumn Fantastic Four and Superman v. Batman will have a lot of world-saving to do. But I suspect those films won’t reduce their heroes to insect size, nor will they call upon armies of helpful ants to defeat the inevitably bald-headed villain, played with a glower and a great wardrobe by Corey Stoll. (I’ve heard there are hair-challenged men out there who’re forming a new Anti-Defamation League protesting the assumption that all bald white guys are up to no good.) At any rate, if you like your derring-do tempered with deadpan humor, Ant-Mannicely fills the bill. Special kudos to Michael Peña as a lovably dim sidekick, and to Disney for its willingness to poke fun at its Marvel-ous connections. (It’s a small world, after all.)

Of course, some folks like their thrill rides to be a bit more realistically scary. I’m told that the brand-new Mission: Impossible – Rogue Nation does a great job in that respect. Frankly, Tom Cruise scares me at the best of times, but (given his enormous physicality and his love for doing his own hair-raising stunts) he truly owns this particular genre. The weekend box-office numbers suggest that, despite his weird marital history and offbeat religious affiliations, Cruise must be doing SOMETHING right.

But of course it’s hard for me to associate Tom Cruise with Mission: Impossible. You see, I’m an old-fashioned girl. And when I think about Mission: Impossible, I’m remembering a TV series that ran from 1966 to 1973. All of us college kids were rooting for the Mission: Impossible team, covert operatives who each week thwarted bad guys on behalf of the U.S. government. There was stalwart Peter Graves, as James Phelps, the grey-haired leader. There was Martin Landau as smart, tricky Rollin Hand. There was Landau’s wife, Barbara Bain, as Cinnamon Carter, Hand’s equal as a master of disguises. There was the hulking Peter Lupus, the team’s designated muscle. Finally, there was Greg Morris. In that era, when civil rights issues were on everyone’s mind, it was important to have a black man on board. And he had to bely old stereotypes by playing a role that was intellectual rather than chiefly physical in nature. So Morris was the team electronics expert. I never knew exactly what he was doing as – under duress -- he switched wires around. But he’d always sweat beautifully, so it was clear that this was very hard work.

Of course, part of the thrill of Mission: Impossible came from Lalo Schifrin’s throbbing theme music. And the series also had a weekly opening that was ripe for memorization and parody. After an exciting montage featuring a burning fuse, Peter Graves would play a mysterious tape recording briefing him on the job at hand. It always contained the words, “Your mission, Jim, should you decide to accept it . . . .” (I certainly don’t recall fearless Mr. Phelps ever turning anything down.) Then came the best part: the tape, as promised would automatically self-destruct.

Years later, when phone machines were new and exciting gadgets, my voice recording told callers that their mission (should they choose to accept it) was to leave a message, or risk automatically self-destructing. Well, it seemed pretty clever back then.

Speaking of threats to the world as we know it, here’s a link to a piece I just published in the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists (yes, really!) on the very serious matter of nuclear radiation, as it pertains to Nevil Shute’s novel (which became Stanley Kramer’s film), On the Beach.

Published on August 04, 2015 12:27

July 31, 2015

Mike Nichols Graduates to “Carnal Knowledge”

Having won acclaim and an Oscar for directing The Graduate in 1967, Mike Nichols soon moved on to bigger projects. The first, an ambitious adaptation of Joseph Heller’s darkly comic anti-war novel, Catch-22, got mixed reviews. For the second, Nichols returned to the funding source (Joseph E. Levine’s Embassy Pictures) and the subject matter (love and sex) that had worked so well for The Graduate. Carnal Knowledge, released in 1971, represents a fascinating follow-up to the affairs of a young man named Benjamin Braddock, who looks to sex to solve all his problems.

Having won acclaim and an Oscar for directing The Graduate in 1967, Mike Nichols soon moved on to bigger projects. The first, an ambitious adaptation of Joseph Heller’s darkly comic anti-war novel, Catch-22, got mixed reviews. For the second, Nichols returned to the funding source (Joseph E. Levine’s Embassy Pictures) and the subject matter (love and sex) that had worked so well for The Graduate. Carnal Knowledge, released in 1971, represents a fascinating follow-up to the affairs of a young man named Benjamin Braddock, who looks to sex to solve all his problems.Carnal Knowledge, scripted by the ultra-hip Jules Feiffer, starts with not one young man but two. At the film’s beginning, as they yak about girls in their dorm room, they’re a long way from graduation. Jonathan (Jack Nicholson) and Sandy (a surprisingly effective Art Garfunkel) are callow Amherst freshmen, and their discussion of sex is purely theoretical. But college life, post World War II, brings its rewards. Sandy is soon head over heels about the smart, savvy Susan (Candice Bergen), a Smith freshman with dreams of law school. Touched by his sweet naiveté, she permits him some . . er . . . liberties. But it’s Sandy’s bolder roommate, Jonathan, who gets her in the sack.

We jump ahead to about 1960. Sandy is now a busy doctor, with Susan as his homemaker wife. He describes their life together as idyllic, but he’s secretly looking to get laid by someone new and exciting. Jonathan, a financier, has been playing the field, but the voluptuous Bobbie (a sizzling Ann-Margret) seems exactly what he craves. As he puts it, “Believe me, looks are everything.”

You should be careful what you wish for. In short order, Sandy’s in thrall to his domineering new squeeze, and Jonathan has lost all passion for Bobbie, who wants marriage and family at any cost. The film jumps forward once more: it’s about 1970 and the men are forty years old. Sandy, now shacking up with a flower child, seems as fundamentally clueless as ever. Jonathan has been reduced to cataloging all the “ball-busters” he’s dated over the years, while forking over $100 bills in return for sexual pleasure at the hands of a pro.

It’s not a pretty picture, in more ways than one. Nichols, who brilliantly captured the look and feel of Southern California in The Graduate, goes a different route here. The Graduate was all sunshine and swimming pools: the visuals made a strong contribution to a story about affluent suburbanites (like Ben’s parents) who give things instead of love. Carnal Knowledge is an east coast story, without that same dramatic sense of place as a catalyst for the characters’ behavior. An Ivy League campus is merely some leafy woods and a dorm room; the characters’ later lives in New York City boil down to some lighted skyscrapers, a cushy office, and a nondescript apartment.

If visuals are not tremendously important, Nichols banks here on sound, both the period pop tunes on the soundtrack (like “I’m Getting Sentimental Over You” at the first dorm mixer) and the voices of the two men in earnest conversation. In fact, the opening credits roll over a black screen, while we listen to them gab about the sexcapades in their future. Later scenes are basically monologues, in which one or the other takes the pulse of his current sex life.

One sad thing: the female characters, once wed or bedded, completely disappear from the narrative. It’s a man’s world, and women like Susan and Bobbie—apparently without jobs or purpose—have no long-lasting place in it.

Published on July 31, 2015 09:03

July 28, 2015

The Art of Making Movies; The Art of Making Art

Hollywood film has always had trouble capturing the making of art by great writers, composers, and painters. This despite the fact that some much-applauded movies have had artists in leading roles. Such movies tend to succeed when they’re less about artistic achievement than about the artist’s colorful but totally screwed-up personal life. Take Van Gogh battling his mental demons in Provence (Kirk Douglas in Lust for Life, 1956). Or Toulouse-Lautrec coping with shriveled legs while dwelling among the demimonde of Montmartre (José Ferrer in Moulin Rouge, 1952). Or Michelangelo lying on his back on a high scaffold in Vatican City, fending off his sexual proclivities as well as an imperious Pope (Charlton Heston in The Agony and the Ecstasy, 1965). Last year the always adventuresome Mike Leigh tried to capture both the art and the era of Victorian painter J.M.W. Turner, but his Mr. Turner was hardly for all tastes.

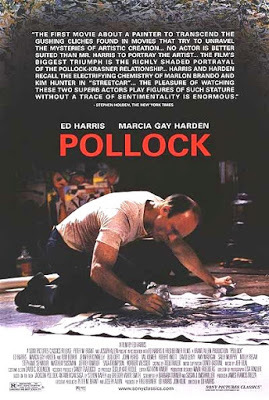

In 2000, there was serious buzz about the rare Hollywood movie that grappled with the life and work of a twentieth-century artist. Pollock, focusing on the career of abstract expressionist Jackson Pollock, largely succeeded thanks to the heartfelt commitment of lead actor Ed Harris (a Pollock lookalike) as well as the kinetic excitement of Pollock’s “action-painting” methods. The drama implicit in Pollock’s tumultuous domestic life and sudden death proved helpful too.

My friend and colleague Cathy Curtis has just published an in-depth biography of another recent painter, and can’t helping wondering if Hollywood might be interested. Restless Ambition looks closely at the life of artist Grace Hartigan, who lived (as Cathy points out) “a life as colorful as her paintings.” There’s no question that Hartigan experienced personal drama. A stunningly attractive woman—as well as a talented expressionist painter—she survived four marriages and a wide array of lovers. The story of her last marriage, to a medical researcher who injected himself with an experimental drug that destroyed his physical and mental capacities, hardly lacks for pathos.

The possibility of Hollywood paying attention to Grace Hartigan would be tremendously apt, given that she herself was hugely influenced by both the myths and the visual stylistics of the motion picture industry. As a young girl watching silent movies, Hartigan was bedazzled by seeing monumental black-and-white images in close-up. These “huge faces on a glowing screen” later encouraged her to choose enormous canvases for her own work. And throughout her career she remained mesmerized by movie queens, movie magazines, and even paper doll collections like Tom Tierney’s Glamorous Movie Stars of the Thirties. Like fellow artists de Kooning and Warhol, she portrayed Marilyn Monroe after her tragic death, hinting in her work what it cost Marilyn to be “the last goddess.”

The general public, of course, has not always been respectful of the work of abstract expressionists. Which reminds me of a wickedly funny little Oscar-winner called “The Day of the Painter” (1960). This fifteen-minute gem, from the era when America movies were often accompanied by short subjects, gently satirizes the “serious” work that goes into creating a lucrative drip-painting masterpiece. I’d love to watch this one again.

Speaking of which, last week saw the death of George Coe, who both directed and starred in another of those great old short subjects. "De Düva" ("The Dove") is an outrageous parody of such solemn Ingmar Bergman classics as Wild Strawberries and The Seventh Seal. It’s performed in pseudo-Swedish, complete with subtitles, by a cast that includes the sublime Madeline Kahn in her first film role. Thanks to YouTube, I here present for your amusement a madcap foray into the art of cinema.

Published on July 28, 2015 12:50

July 24, 2015

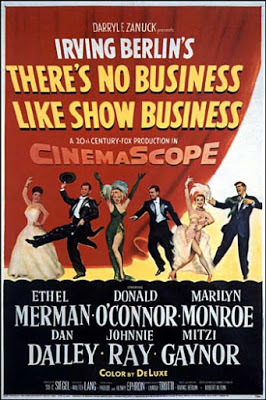

The Son (of Ethel Merman) Also Rises

F. Scott Fitzgerald once said that the rich “are different from you and me.” One look at Donald Trump and you know that’s true. It’s clear -- no matter how you feel about Trump’s presidential ambitions -- that everything he does is shaped by his awareness of his own wealth and power.

Some people, including Scott Fitzgerald, deeply admire the wealthy. Others distrust society’s “haves,” and identify with the have-nots. Few feel more strongly than those who’ve grown up surrounded by privilege, all too aware that our nation’s one-percenters don’t always use their gifts well.

Take the case of my new friend Bob, who’s the son of Broadway and Hollywood legend Ethel Merman. His father, who died when he was twelve, was a successful businessman. His stepfather owned Continental Airlines, and pursued side ventures (like flying troops to Vietnam and flying bodybags home) that made him heaps of money in the late Sixties. Bob vividly remembers an argument in which his mother shrieked at his stepdad, “You use me to get to Nixon for your goddam contracts for your goddam war.”

Bob grew up in posh surroundings on Manhattan’s Central Park West. There was a friendly doorman, and an annual party for the building’s kids, who’d gather to watch the floats of the Macy’s Thanksgiving Parade at eye level. The family’s 21st story duplex boasted its own wraparound terrace, complete with lily ponds. Unfortunately, it also boasted what he calls a “Fascist” governess, who at bedtime made him recite the Lord’s Prayer in German.

None of Bob’s parental figures gave him much in the way of attention. Nor did they encourage him to develop a sense of empathy for those who had less: “You didn’t get involved with fans. At best you gave them an autograph. You didn’t get involved with the working class. At best you gave them a tip.”

During his mid-teen years, Bob was “spinning in my undeveloped, unparented juices.” When Merman went on the road as the star of Gypsy, he convinced her to let him live on his own, in a residence hotel on the Upper West Side. Needless to say, he didn’t bother with school attendance; he was too busy using his mom’s charge accounts to take cute young things in the Bye Bye Birdie cast to Sardi’s. Merman was angry, because she expected good behavior – but she never seemed much concerned about how he’d make his own way in life.

Fortunately, Bob slowly gravitated into theatre work, of the backstage variety. He got his first gig because of family connections, and deserved to be fired for a long list of screw-ups. But somehow he acquired kindly mentors, who’ve seen him through good times and bad. Today he spends long hours working for environmental causes. And he’s tremendously proud of the homeless boy from the streets of L.A. who’s become his adopted son.

Ethel Merman, of course, was famous for her powerful singing voice. Didn’t he and she ever sing together? Well, yes. . . for a while their bedtime ritual (before she left for the theatre) was to duet on a ditty called “Play Ball.” The unspoken deal was that if any words came out wrong, they’d have to start again from the beginning. So he’d mangle the rhymes in hopes of having his mother to himself just a bit longer. Shrugs Bob, “That was our sharing, pretty much.”

Today Bob still mistrusts the rich. He firmly believes that once we come to see “wealth as surplus, fame as distraction,” the world will finally begin to heal itself.

Published on July 24, 2015 11:09

July 21, 2015

A Provocative Question -- Feminists: What Were They Thinking?

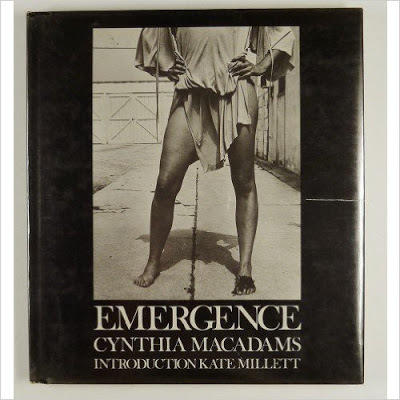

The ever-enterprising Kat Kramer, known for her Films that Change the World series, hosted a small soiree the other evening to promote a fascinating work-in-progress, Feminists: What Were They Thinking? This documentary, produced and directed by veteran filmmaker Johanna Demetrakas, takes as its starting point the photos published in 1977 by Cynthia MacAdams as part of a collection called Emergence. MacAdams had approached a number of strong women, some but not all of them rising stars in the arts world. She captured them in black and white to suggest the evolving role of feminism in American life. It’s been said that in Emergence “the women look back at you.” As you flip through the pages, it’s clear they are far more than objects posed to attract the male gaze.

Demetrakas and her team (made up of both women and men) had the bright idea of looking in on MacAdams’ subjects, to see how they’d fared over the past forty years. Most are emphatic in stressing why they embraced feminism in the Seventies, and why they continue to value it now. Musician and performance artist Meredith Monk remembers back to her girlhood, when she was denied a train set. When, back in grade school, she had a young male visitor, her mother instructed her to make sure to let him win any games they played. Psychotherapist Phyllis Chesler recalls that “I was the smartest ‘boy’ in Hebrew School class.” Unable to have a Bar Mitzvah, she rebelled by turning against her parents’ religious Orthodoxy, to the point of eventually marrying a Muslim and accompanying him to his father’s polygamous home in Afghanistan. (The experience resulted in a book, An American Bride in Kabul, as well as a lifelong commitment to women’s issues.)

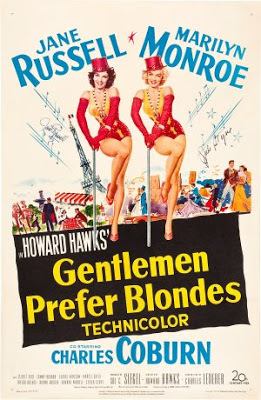

The film juxtaposes such interviews with film clips and TV commercials that make clear Hollywood’s longtime objectification of the female of the species. There’s Marilyn Monroe, cooing and jiggling in Gentlemen Prefer Blondes, and an ad for a Suzy Homemaker toy kitchen that, remarkably, was still being sold as recently as 2007. My personal favorite is the winsome lass in the tight dress who breathlessly explains to the camera that “I can’t type, I don’t take dictation. My boss calls me indispensable. I push the button on the Xerox 914!” But there’s also a happy housewife, circa 1950, who joyfully twirls on her way to fill the tea kettle, played off against journalist Susan Brownmiller’s wry questions, “Why do we smile so much? Why do we try to be so appealing? . . . Why is anger considered not feminine?”

One of the film’s most articulate speakers is, not surprisingly, Jane Fonda, who poignantly remembers her adolescent fear that “if I wasn’t perfect I wouldn’t be loved.” Still, she notes, little girls are feisty before puberty sets in. Now “as I’ve gotten older, I’ve come back to where I’ve started, as that feisty girl who would climb to the top of the oak tree, and lead armies up the hill, and knew who she was, and would stand up to anything, and never told a lie.”

Everyone interviewed thus far continues to be a staunch supporter of the feminist cause. But Johanna Demetrakas, committed to exploring cultural change in all its manifestations, will not exclude any point of view that presents itself: Says she, “I don’t know where the film’s going. I go with the film.” What she wants above all is for her audience to feel that they’ve joined the conversation.

Of course she also wants (and needs) financial support. To get involved, check out http://www.feministswhatweretheythinking.com

Published on July 21, 2015 12:51

Beverly in Movieland

I write twice weekly, covering topics relating to movies, moviemaking, and growing up Hollywood-adjacent. I believe that movies can change lives, and I'm always happy to hear from readers who'd like t

I write twice weekly, covering topics relating to movies, moviemaking, and growing up Hollywood-adjacent. I believe that movies can change lives, and I'm always happy to hear from readers who'd like to discuss that point.

...more

- Beverly Gray's profile

- 10 followers