Beverly Gray's Blog: Beverly in Movieland, page 103

January 8, 2016

Trumbo: What’s in a Name?

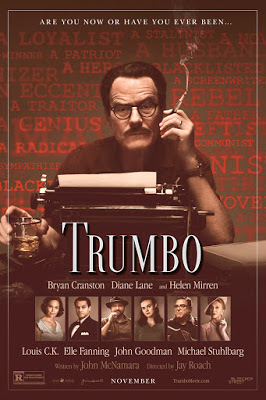

The long shadow of the Hollywood blacklist is still with us. This is made clear by the 2015 film Trumbo, which twice shows its hero, Dalton Trumbo, sitting on a couch with his family, watching on TV the Oscars he’s won for his screenplay be awarded to others. Trumbo was a difficult kind of guy, often truculent, sometimes plainly naïve, but warm and generous beneath it all. He was also a loyal husband and father, who needed to provide for a family left bereft when he was sent to prison for defying the House Un-American Activities Committee in 1947. As one of the so-called Hollywood Ten, he could not be hired by a Hollywood studio, even after his eleven-month stint in the federal penitentiary was completed. That’s why he, like so many blacklisted writers, was forced to sell his scripts under the names of others.

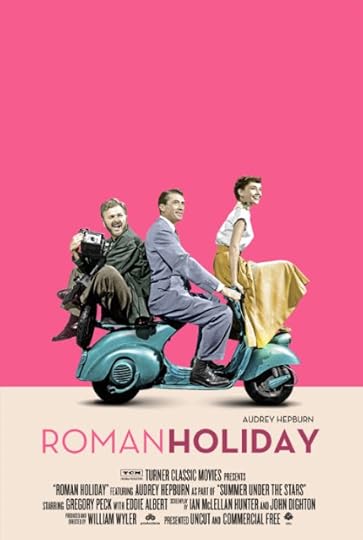

A 1976 film, The Front, showed us how that system worked. The Front, starring Woody Allen in the rare role he did not write, suggested the psychological toll on an average little man who has agreed to take credit for the achievements of others. In Trumbo, we see the situation from the true author’s perspective, in the context of Roman Holiday, a delightful 1953 romantic comedy with absolutely no political undertones. Because of the rules of the blacklist, Trumbo could only sell it by persuading a fellow screenwriter, Ian McLellan Hunter, to take credit where credit was not due. Roman Holiday won the 1954 Oscar for best original story, and a rather embarrassed Hunter duly received a golden statuette bearing his name. (This error was not rectified by the Academy’s Board of Governors until 1992, when Trumbo’s widow accepted his Roman Holiday prize, but sites like IMDB still list Hunter as one of the film’s actual writers.)

The second time around, rather than turning to a fellow screenwriter as a front, Trumbo borrowed the name Robert Rich from the nephew of his bottom-of-the-barrel producer, Frank King. The film was The Brave One, a tender tale about a young Mexican boy and his bull. When the name Robert Rich was called by the Academy Awards presenter, no one came forward. This Oscar was re-issued in Trumbo’s own name in 1975, once the power of the blacklist had been broken once and for all.

The film Trumbo (which boasts a terrific lead performance by TV favorite Bryan Cranston) is based largely on the memories of Trumbo’s two surviving children. If the film is to be believed, Trumbo did a masterful job of engineering an end to the blacklist by playing two big Hollywood personalities off against one another. Circa 1960, a brash young Kirk Douglas was angling for Trumbo to write Spartacus, about a slave revolt in ancient Rome, with Douglas himself producing as well as playing the leading role. At about the same time, the imperious director-producer Otto Preminger sought Trumbo’s expertise in transforming Leon Uris’s bestselling Exodus into a screenplay. What Trumbo wanted, above all, was a chance to write under his own name once more. By skillfully appealing to the oversized egos of Preminger and Douglas, he got both to agree to give him screen credit.

Dalton Trumbo was clearly not a man without flaws. But the real bad guys of this complicated story are those who seek to deny First Amendment rights to Americans who hold unpopular opinions. Gossip columnist Hedda Hopper certainly had the right to come down hard on the “Reds” whose reputations she tarnished in the press. But, in Helen Mirren’s poison-pen performance, she’s a woman I loved to hate.

Published on January 08, 2016 23:28

January 5, 2016

Take a Picture -- It Lasts Longer

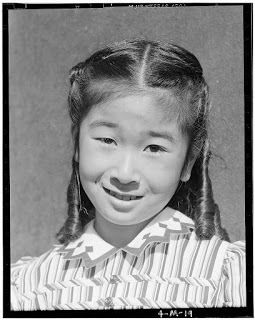

Photo of Manzanar resident by Ansel Adams

Photo of Manzanar resident by Ansel AdamsPhotography is fundamental to the motion picture medium, which is why the recent loss of the veteran cinematographers Haskell Wexler (on December 27) and Vilmos Zsigmond (on January 1) hit Hollywood so hard. But still-photography is important too. Every movie set has its official still photographer chronicling the action, and actors use artful headshots to help them find work. There’s also the value of shocking news photographs, which can inspire moviemakers into telling the story behind the photo. The real Clyde Barrow and Bonnie Parker liked to photograph themselves posing with their weapons, and director Arthur Penn (whose brother was the great photographer Irving Penn) used photography as a leitmotif throughout his masterpiece, Bonnie and Clyde.

I’ve been thinking about photography a lot lately, partly because of a disturbing report I heard on my favorite Public Radio station. It seems some nursing home attendants have developed the nasty habit of photographing elderly residents (many in the throes of dementia) with their cell phone cameras, and then posting the often-grotesque pictures to social media outlets. Though their shots are clearly mean-spirited, they often can’t be called to account because photos on sites like Snapchat quickly vanish, leaving behind no evidence of wrong-doing. As hateful as this practice is, what intrigues me is the possibility that a photo can leave no trace. After all, the whole point of photography was once the fact that it created a permanent record out of a fleeting moment. I once saw a highly moving exhibit of the photo-portraits of Civil War soldiers. Before marching off to battle, soldiers on both sides of the conflict often posed for stiff photographs of themselves in uniform, then sent these to their loved ones back home. In many cases, the photo was all the family had left to remember a husband or a son who didn’t return.

For those Civil War soldiers, having a photo taken was a once-in-a-lifetime experience. By the mid-twentieth century, we were all used to being photographed, at least on special occasions. Most people owned simple cameras, but the shots they took generally didn’t stand the test of time. Still, in the right hands, a camera could be a potent weapon. That’s what occurred to me when I saw an important exhibit on the photos shot at Manzanar by one of America’s most admired photographers, Ansel Adams.

Manzanar, of course, was one of the internment camps to which 120,000 Japanese-Americans (most of them U.S. citizens) were consigned after the attack on Pearl Harbor made the U.S. government paranoid about possible sabotage within American borders. Located in California’s high desert at the foot of Mt. Whitney, the Manzanar site was starkly beautiful, but also desolate and unforgiving. The U.S. government sent Dorothea Lange, well-known for her photos of the Dust Bowl, to chronicle camp life, but forbade her to show such realities as guard towers and barbed wire. When her photos were deemed too sympathetic to the camp’s inhabitants, they were suppressed. Fortunately for history, Ansel Adams befriended the camp’s director and from 1943 through 1944 set about shooting memorable black-and-white portraits (of children, adults, elders) for a book he later called Born Free and Equal: The Story of Loyal Japanese-Americans.

There was one more chronicler of Manzanar. Toyo Miyatake, a studio photographer by trade, was interred along with his family. He managed to smuggle in a camera lens, built a crude camera body, and at first covertly (and later with permission) captured invaluable images of Manzanar life. It was a harsh life, but one that revealed the stoic nobility of people who didn’t deserve their fate.

Published on January 05, 2016 12:47

January 1, 2016

Star Wars Goes to Brooklyn

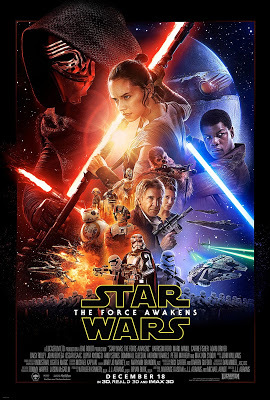

Yes, over the holidays I saw the new Star Wars film, The Force Awakens. And yes, I thoroughly enjoyed it. I’ve read many of the gripes from über-fans, like the one about how this new flick is derivative, and how it lacks the mythological profundity with which George Lucas laced his original Star Wars universe. There’s not enough of Joseph Campbell’s Hero of a Thousand Faces in the J.J. Abrams approach? Frankly, my dear, I don’t give a damn. I expected from The Force Awakens an entertaining thrill-ride, a sort of audio-visual theme park attraction, and that’s exactly what I got.

Certainly this film was a lot more fun than a critics’ darling of a movie, like Todd Haynes’ Carol. Not that I’m opposed to a carefully-crafted drama that broaches thorny social issues. Not that I’m at all upset by a euphoric depiction of lesbian love. But Carol, for all of its fine acting and visual gloss, left me stone-cold. I was deeply moved by an earlier Todd Haynes film, Far from Heaven, that looked at similar social issues, once again in the context of the repressive 1950s. But even with Cate Blanchett and the piquant Rooney Mara in Carol‘s leading roles, I couldn’t warm to a tale about a wealthy, pampered woman who was being denied what she REALLY wanted for Christmas.

The end-of-year holidays are a terrific time for binge moviegoing, especially with family and friends. That’s how I happened, the night after seeing Star Wars, to go to my favorite multiplex to watch for the second time one of my favorite 2015 movies, Brooklyn. It is, of course, a romantic drama about Irish immigration to New York City, starring the young and talented Saoirse Ronan. To my delight, my husband found himself genuinely moved by this simply story, which sadly is often labeled a “woman’s picture.” And to my surprise, Brooklyn and The Force Awakens turn out to have a great deal in common. Don’t believe me? Read on . . . . We all know, by now, that this is the diversity Star Wars, with leading heroic roles played by a black man (John Boyega as ex-storm trooper Finn), a Latino (Oscar Isaac doing an updated Han Solo), and a woman (Daisy Ridley as the tomboyish Rey). We also know that it’s the nostalgia Star Wars, one that honors its roots by finding key roles for Harrison Ford, Carrie Fisher (now a general as well as a princess), and Mark Hamill.

I want to concentrate here on Rey. Is she so very different from Brooklyn’s Eilis Lacey? Both leave homes that lack what they need to travel to kingdoms far far away. Both are tempted -- more than once -- by attractive men of very unfamiliar backgrounds. Both must decide what they want out of life, and both films hinge on the choices these young women make. Both crave, and deserve, love, but it develops as they discover their own talents for leadership. Rey learns she’s being guided by the Force, and I’d like to think Eilis feels some of that too, even though her great skill lies not in combat so much as in double-entry bookkeeping.

In one area, they’re profoundly different. Eilis’s evolving wardrobe indicates her growing maturity and sophistication. Rey, though, wears the same practical grey outfit throughout. (She even wears it in a childhood flashback, presumably in a much smaller size.) Eilis also learns to apply makeup. Surprisingly, Rey wears eye makeup too. She may hail from a small desert planet, but a movie heroine wouldn’t be caught dead without her mascara.

A very happy, healthy, and peaceable New Year to all my readers.

Published on January 01, 2016 16:05

December 29, 2015

The Many Successes of Haskell Wexler

As a writer who focuses on Hollywood, I’ve been very lucky. In 2008, for over two hours, I had Haskell Wexler as a sparring partner. Wexler, the eminent cinematographer who died Sunday at age 93, was widely known to be opinionated, even cantankerous. He had a strong social consciousness, and didn’t suffer fools gladly. When I was researching Hollywood films of the late 1960s, I badly wanted to discuss with Haskell his first directorial effort, 1969’s Medium Cool. It’s about a news cameraman (played by Robert Forster) covering the violence surrounding Chicago’s 1968 Democratic National Convention. Shot in the style of a cinéma vérité documentary, it explores one of Wexler’s favorite philosophical themes, the overlap between fact and fiction. As he sees it, “There are no facts. Just people’s fictions.”

I had plenty of questions when I showed up at Haskell’s airy Santa Monica condo. At first he was polite but rather cool, giving rambling philosophical answers with the air of someone who’s quite accustomed to being listened to. He made sure I knew that Hollywood movies, even those with an idealistic political bent, are first and foremost all about making money, which is why they take great care not to give offense. A good example from the seminal year 1967 is In the Heat of the Night, the Oscar-winner on which Haskell served as cinematographer after turning down an opportunity to shoot The Graduate. (His previous collaboration with director Mike Nichols, Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?, had won him his first Oscar. He wanted to work with Nichols again, but had taken a principled stand against doing projects he didn’t like, and The Graduate fit into that category.)

My real breakthrough with Haskell came when I asked about Blow-Up, the surrealistic Antonioni film which like Medium Cool has a photographer as its protagonist. As a lover of European art films, Haskell confirmed that Blow-Up was hugely important to him. But, always skeptical about conventional American tastes, he lamented that this film had never gotten its due in Middle-America. I disagreed, noting that Blow-Up was a big box-office hit. “Yes,” said Haskell, “but a big hit in what circles? Not in Ames, Iowa. Not in . .” That’s when I dared to cut him off, pointing out that the film’s bold use of frontal nudity had Americans of every stripe flocking to their local cinemas. Said he, “I stand corrected.”

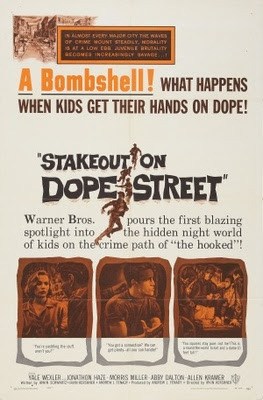

After I locked horns with Haskell, he seemed to truly appreciate me. I ended up being filmed with him by documentarians Joan Churchill and Alan Barker, and even got to stay for lunch. He introduced me as someone who, like him, had started with Roger Corman. Yes, the great Haskell Wexler too was a Cormanite. As a union cameraman, he couldn’t be credited on a non-union Corman film. But he shot Stakeout on Dope Street as Mark Jeffrey, creating a pseudonym from the names of his sons. He told me, “I’m fascinated by you, because you worked very closely with Roger Corman, for a long time. Roger Corman was not on the barricades. Roger Corman was a man of the system, but like an independent businessman up against the corporations. And how Roger --- you say he saw himself as an independent guy doing things that the system didn’t or wouldn’t do -- is part of the American ideal of the little guy pulling himself up by his bootstraps and becoming a success. Because we still accept the definition of a success, as Roger did, as making money.”

By any standard, Haskell Wexler was a success. Hail and farewell.

Published on December 29, 2015 11:44

December 25, 2015

Roger Corman and the Gift of Giving

‘Tis the season for gift-giving. Most of us who’ve had the good fortune to work for Roger Corman realize we were given a significant gift. Not a monetary gift, to be sure. Our salaries tended to be so low that they could hardly be considered a living wage. And once Roger discovered that eager young filmmaking hopefuls would work for free, he was quick to embrace the Hollywood tradition of unpaid internships. Years ago, writer-director Howard R. Cohen told Roger that no one could live on the salaries he offered. Roger, though, had a quick response: “I get the money; you get the career.”

At this time of merry-making, it’s appropriate to pass along the story of the Christmas parties at Concorde-New Horizons. Yes, we normally had a little party, downstairs in the cramped first-floor lobby of our shabby Brentwood office building. We also each received what I must admit was a fairly generous bonus check. One year, though, profits were off. And so Roger democratically offered us a choice: the party or the bonus. Guess what we all chose? We had certainly learned from our boss that money comes first. Anyway, the party was really nothing special. Nor did it require much expenditure on Roger’s own part. Possibly Roger himself sprang for a few bottles of wine, or some paper plates. And wife Julie contributed homemade Irish soda bread. Lavish it was not!

But let me move beyond Christmas to mention some of the gifts Roger gave to his underlings. He gave, above all, the gift of opportunity. Sometimes this was a mixed blessing. While making a film you could be sent to Peru, to be hassled by the Shining Path guerrillas. Or travel to Bulgaria or Moscow or the Philippines, where fledgling director Carl Franklin was drugged with an animal tranquilizer in a Manila nightspot, probably by someone planning to rob him. Possibly it was an attempt at something more sinister, like a kidnapping by a revolutionary group. Happily Carl survived, and no one tried asking Roger to fork over a million-dollar ransom. It’s a good bet he might have said, “A million dollars? I could do six films for that!” When we traveled on Roger’s dime, a dime was pretty much all he spent.

Still, no one can deny that Roger made things happen. At New World Pictures, Gale Anne Hurd—a well-educated Corman assistant with no practical filmmaking background—took her first steps toward becoming a big-league producer. James Cameron wandered onto the set of Battle Beyond the Stars with an idea of how to build a front-projection camera rig for inexpensive special effects shots. Though this wasn’t a success, he started crafting spaceship models, and then segued into becoming the film’s art director, devising sets out of little more than hot glue, gaffer’s tape, spraypaint, and the styrofoam McDonald’s hamburger boxes with which he lined the interior walls of the main spacecraft. On his next film for Roger, Galaxy of Terror, Jim directed second unit. Onward and upward!

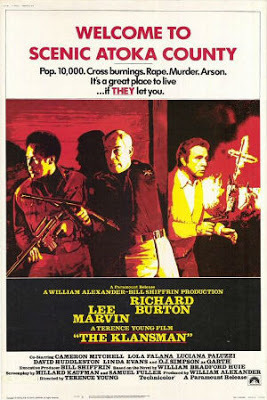

Then there was a young actress, Jeanne Bell. A petite but curvaceous former Playboy playmate, she was cast as the lead in Roger’s TNT Jackson when another actress showed up pregnant. Not the sharpest tool in the shed, she asked me how she should spell her first name. (She was born Mary Ann.) In 1974 she rated a photo in Time magazine for romancing Richard Burton on the set of The Klansman. Elizabeth Taylor was not amused. But such is Hollywood, where opportunities abound for moving up in the world—even if you start with Roger Corman.

Dedicated to Errol Thomas, self-described Roger Corman fiend,who wanted more about Jeanne (or sometimes Jeannie) Bell.

Published on December 25, 2015 15:43

December 22, 2015

Star Wars, Roger Corman-Style, Part Deux

When last we looked in on Roger Corman, he was launching his own bargain-basement version of Star Wars. George Lucas’s original space opera didn’t cost much by today’s standards: its budget is estimated at $11 million. Still, Roger’s 1980 attempt to jump on the intergalactic bandwagon, Battle Beyond the Stars, cost less than half as much—and it showed. Special effects were something new in Cormanland, and the results were not always convincing. But although Battle Beyond the Stars lacked the polish of a big studio production, it launched the careers of a surprising number of people who became Hollywood stalwarts.

The screenwriter of Battle Beyond the Stars, John Sayles, was not brand-new to the wonderful world of Corman. A successful writer of short fiction, he had been discovered in the pages of Esquire by my good friend Frances Doel, when Roger was looking for someone who could be converted into a low-cost screenwriter. Sayles’ first Corman flick was Piranha, Roger’s 1978 attempt to ride on the coattails (or perhaps the fishtails) of Jaws. He also wrote a New World gangster opus, The Lady in Red, and then put his earnings—as well as his growing understanding of cinema—to work in a small film of his own, Return of the Secaucus Seven. Sayles was the man responsible for finding a way to set The Magnificent Seven in space, on a Roger Corman budget. He would go on to become a well-paid Hollywood script doctor, as well as an indie filmmaking legend.

The late James Horner (whom we sadly lost this year in an airplane crash) was not new to Corman’s New World Pictures either. He had composed the score for The Lady in Red, as well as for a particularly schlocky Corman fish-tale, Humanoids from the Deep. Horner’s work on Battle Beyond the Stars so impressed Roger that he gave it his highest accolade: over the next thirty years, Cormanites continually borrowed from it to score other Corman movies. But Horner became much better known for Titanic.

For two other Corman protégés, Battle Beyond the Stars was truly life-changing. Gale Anne Hurd, who had been one of Roger’s ace office assistants but wanted to move into production, served as assistant production manager on the film. She found working in Roger’s ramshackle Venice studio unforgettable. As she told me, “Half the time it would be raining and the roof leaked, and there’d be four inches of water on the ground, and people were using power tools while standing in the water. Thank God OSHA never came by, and thank God nobody died.”

With work going on nearly ‘round the clock, death sometimes seemed a distinct possibility. One day Hurd was going over costs and schedules with James Cameron, the film’s new art director, when they heard a piercing scream. It seems a crew member kneeling on the floor had stuck a matte knife in his pocket, its blade protruding. A second man had tried to step over him, but the unseen blade caught his leg, severing his femoral artery. Blood spurted dramatically; he was convinced he was going to die. Hurd told me, “Jim had the presence of mind to take his shirt off, make a tourniquet, tie it, and we both drove him to the hospital.” Within hours, the wounded man was back on the set. Cameron’s heroics obviously made an impression on Hurd. They eventually married, and collaborated on such films as The Terminator, which elevated them both into Hollywood royalty.

But who directed Battle Beyond the Stars? Well, that’s another story.

Published on December 22, 2015 13:37

December 18, 2015

Roger Corman: When The Force Was With Him

No, I don’t have any up-close-and-personal stories about the making of the original Star Wars. But I can disclose how George Lucas’s 1977 space opera helped change the way Roger Corman did business. My former boss was always a master at jumping on bandwagons. When Jaws made oceans of money in 1975, Roger commissioned a film about an even more lethal (though much smaller) fish, Piranha. And the success of Star Wars convinced him that he too needed to produce an intergalactic thriller.

When Corman founded New World Pictures in 1970, he had no studio of his own. Most of his films, like Big Bad Mama and Death Race 2000, were shot on practical locations, giving them a rough vigor prized by many fans. When we shot Candy Stripe Nurses, our hospital scenes took place at a local home for wayward girls that had recently been shut down. But once Roger decided to make his own low-budget Star Wars, he knew he needed interior space in which to create elaborate settings and shoot special effects. The result was the purchase of a property near Venice Beach. It had been the site of a now-defunct lumber yard. A ruling by the California Coastal Commission, a band of ageing hippies terrified of gentrification, forbade Corman from modernizing the exterior of the facility in any way. So the Hammond Lumber sign remained in place (Roger balked at the cost of its removal), and the studio continued to look like a decrepit DIY headquarter. Occasionally an innocent would wander through its gates in search of a two-by-four The late writer-director Howard R. Cohen once told me that he and Roger were standing outside the main soundstage when a would-be carpenter inquired about purchasing some wood. They politely explained that this was now a movie studio, and he went on his way. Afterwards, though, Roger turned to Howard, gestured to the clutter all around them, and said, “You know, I could have made some money off him.”

The studio lot, on Venice’s Main Street, was 50,000 square feet, or about half a city block. It boasted three rather makeshift soundstages, one of them housed in a tin shed. There was also a ramshackle wooden post-production building that had been sinking steadily for years, and was regarded with suspicion by the fire marshals. Challenges abounded. The shooting stages were never properly soundproofed, and because the site was located directly in the flight path for Los Angeles International Airport, production had to grind to a halt when a plane flew overhead. Ambulances and motorcycles, both frequent in that neighborhood, also pierced the silence that filmmaking demands.

Corman’s answer to Star Wars, 1980’s Battle Beyond the Stars, was made as a co-production with Orion Pictures. Roger claimed to have invested $2 million out of a total $5 million budget, although he’s notoriously prone to exaggerating his own expenditures. In any case, the film raked in $11 million—not exactly Star Wars numbers, but an impressive total for a Corman flick. The plot hinges on the notion of transporting The Magnificent Seven to outer space. In the Corman film, a band of scruffy space jockeys is recruited by a young farmer to save his peaceful planet from enemy invaders. The Magnificent Seven, featuring a clutch of American frontier roughnecks who ride into Mexico on a rescue mission, itself borrows directly from Akira Kurosawa’s great Japanese jidaigekiepic, The Seven Samurai. In moviemaking as in Dr. Seuss, “Oh, the places you’ll go!”

It’s so much fun talking about Battle Beyond the Stars that you can expect a continuation next week.

A gentle reminder: the updated, unexpurgated 3rd edition of my Roger Corman: Blood-Sucking Vampires, Flesh-Eating Cockroaches, and Driller Killers is newly available as an audiobook, ideal for holiday listening.

Published on December 18, 2015 13:56

December 15, 2015

Introducing Dorothy Ponedel: She’s Why the Stars Had Faces Back Then

Makeup by Dorothy Ponedel

Makeup by Dorothy PonedelIn this season of family gatherings and warm family memories, Meredith Ponedel thinks back to her Aunt Dorothy. Meredith had lived with her father’s sister since her mother died when she was only three. The woman in whose Beverly Hills home she grew up had white hair and needed a walker, the result of the MS that struck her when she turned 50. There was little question in young Meredith’s mind that Aunt Dot was an old lady of no particular consequence. Still, there were those glamorous photographs that five-year-old Meredith had unearthed in the attic. When she began asking questions about her aunt’s past, an amazing story emerged.

Dorothy Ponedel, it seemed, had been a valued member of the Hollywood film community.

Born in 1898 to a Chicago cigar-maker and his wife, Dot Ponedel was faced early on with the need to help support her many relatives. In her teens she made the trek to Southern California with her mother, then sent for brothers and cousins, finding work for everyone within the fledgling studio system. She herself began as a dancer, doubling for Mabel Normand and other stars of the silent era. She played hookers and a hula girl, as well as what she liked to call “the First Tonto.” (In films like 1925's Galloping Vengeance she wore a wig and dark makeup to play an androgynous Indian guide.) In that wild and woolly era, she was fortunate to be feisty and outspoken. She staved off the advances of many a director, and (when asked to pose nude) retorted, “I want all my interesting points draped, or no go.”

Soon Dot discovered she had a special talent for movie makeup. By studying the light and shadows in the paintings of great artists, she learned to highlight the best features of Hollywood’s leading ladies. The penciled-in eyebrow look that dominated the 1930s was largely her doing. Unfortunately, the formerly all-male union of Hollywood makeup artists kept trying to oust her from its ranks. When she was under contract at Paramount, both Marlene Dietrich and Mae West refused to come to work unless she was permitted to remain a union member.

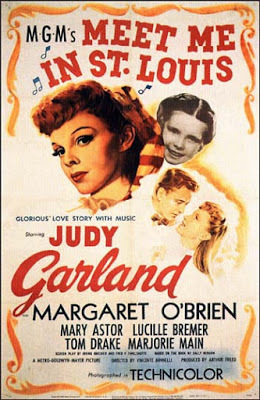

Always sociable, Dot entertained many glamorous stars in her home. Joan Blondell often visited, as did her favorite Hollywood pal, Judy Garland, with whom she shared a raucous sense of humor. Niece Meredith enjoyed these visits, though not the girly gifts the ladies sometimes brought her, like frilly underwear. Nor did Meredith relish lunching on Garland’s homemade Shepherd’s Pie. But her aunt made clear that, when celebrities came to call, “she didn’t want me to know them as movie stars. She wanted me to know them as people.”

As Dot Ponedel grew older, her illness made it difficult for her to work. Still, she liked having company. When Meredith was a student at nearby Beverly Hills High, Aunt Dot would sometimes summon her to come home in the middle of the day by staging a “crisis.” Meredith will never forget the day in junior high she was given the alarming news that her aunt had fallen from her wheelchair. She was driven home by the school nurse, who helped Dot back into her chair, but was shocked by the extent of the blood and bruises that covered her face and body. After the nurse departed, Meredith learned the truth: her aunt’s ugly wounds were nothing but makeup. She just wanted to have her niece around for the afternoon.

Dorothy Ponedel died in 1979, but has not been forgotten, As Angela Lansbury once confirmed, “She walked onto the set and everybody smiled.”

Judy Garland, at the time she shot "In the Good Old Summertime," surrounded by her entourage. Dot, wearing a white blouse, is just above her right shoulder. The ladies are studying photos of little Liza Minnelli

Judy Garland, at the time she shot "In the Good Old Summertime," surrounded by her entourage. Dot, wearing a white blouse, is just above her right shoulder. The ladies are studying photos of little Liza Minnelli An early photo of Dot Ponedel on the Paramount Studios lot Her hair color reportedly changed from week to week.

An early photo of Dot Ponedel on the Paramount Studios lot Her hair color reportedly changed from week to week.

Published on December 15, 2015 11:56

December 11, 2015

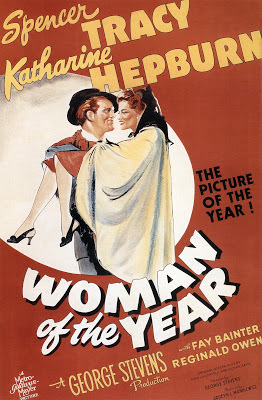

Katharine Hepburn and Angela Merkel: “Woman of the Year”

Back in 1942, Katharine Hepburn starred in a domestic comedy called Woman of the Year. She played a hotshot career woman who kept up her hectic lifestyle even after marriage to fellow journalist Spencer Tracy. In a typically quixotic move, she brought home a Greek war orphan she’d decided to adopt as a humanitarian gesture. Then she felt no qualms about leaving this tiny child to his own devices as she swept off to accept a “Woman of the Year” award for her skill at balancing professionalism and femininity. Naturally, this negligence prompted a romantic crisis with Tracy that required the rest of the film to solve.

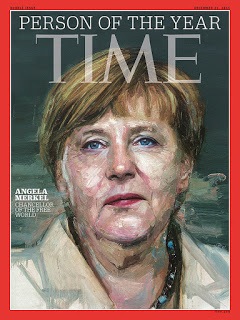

This week Angela Merkel was named Time Magazine’s “Person of the Year.” It’s only the fourth time that the familiar “Man of the Year” honor has gone to an individual woman (rather than to a married couple or a symbolic collective of women). The very first, Wallis Simpson, was recognized in 1936 because of her role in prompting the abdication of England’s Edward VIII. So she was famous more as a romantic object than as, in any sense, a leader. The second female honoree was Queen Elizabeth II, at the time she inherited Great Britain’s throne from her father, George VI. The third was Philippine president Corazon Aquino, in 1986. Aquino was, unlike Elizabeth, an actual elected head of state, though her powerbase evolved out of her marriage. She considered herself a housewife until the assassination of her spouse, Benigno Aquino, pushed her into a position of power. All three previous Timehonorees were hailed in their cover photos as “Woman of the Year,” a phrase which sounds as though it came from a Hepburn movie, or a beauty pageant.

Angela Merkel, though, is a genuine political powerhouse, a trained scientist-turned-politician whose leadership of Germany has shaped the face of Europe at a time when monetary and refugee crises threaten to topple western civilization. I’m delighted that Time singled her out: among the other finalists were some pretty hideous specimens of humanity. But faced with immigrants flooding into Europe from the war-torn Middle East, she has shown diplomacy, courage, and a warm heart. And, importantly, her rise has had nothing to do with her spouse or her family situation

For a writing project, I once studied Time’s weekly covers from October 1966 through June 1968. During the span of more than 18 months, only about a half-dozen women appeared on the cover of Time. They included Julia Child (for the Thanksgiving issue in November 1966), Julie Andrews (December 22, 1966), Lynn and Vanessa Redgrave (two sisters nominated for Best Actress Oscars in March 1967), and Aretha Franklin (headlining the Sounds of Soul issue, June 1968). The “Man of the Year” edition that hit newsstands in January 1966 was called “Twenty-Five and Younger.” It was a salute to Baby Boomers, and although a token female was included in the cover sketch, along with a young black and young Asian-American male, the cover was dominated by the image of a short-haired young white male. Certainly of interest to women was the cover story on social implications of The Pill (April 7, 1967). And on September 29, 1967, Time’s cover was graced by a news photo taken at an interracial wedding, the then-controversial union of Secretary of State Dean Rusk’s daughter to an African-American classmate. The cover hailed them as “Mr. and Mrs. Guy Smith.”

My point is that back then most women on Time’s cover were entertainers or wives. How lovely to hail Angela Merkel for her achievements in the wider world.

Published on December 11, 2015 11:36

December 8, 2015

Hollywood and the Death Industry: Remembering Our Loved Ones

Facebook users have doubtless spotted startling notifications on the right-hand margin. Here’s one sample: “We Say A Sad And Somber ‘Goodbye’ To The Wonderful Betty White . . . BREAKING NEWS . . . Betty Is Gone.” There’s a pensive photo of White too, strongly implying that the 83-year-old comedy star has suddenly gone to her eternal reward. Staunch Betty White fans will doubtless click on the accompanying link, only to find that this is a sneaky ad for some kind of skincare miracle-product. I admit I’ve succumbed to my curiosity and checked out a similar link connected with the wonderful (and not very young) Judi Dench.

It’s amazing what we’ll do when we’re lured in by news of dead and dying celebrities.

My mind is so boggled by the carnage of the past week that I can barely focus on the conventional life cycle, from which people depart at an appropriately advanced age. There’s a lot of that in Hollywood movies, often featuring touching deathbed scenes that are far too sanitized to resemble actual life. But Hollywood’s fascination with death also extends to the bizarre and the gruesome demise. When I worked for Roger Corman, we took great pains to pump up the gore in our movies and suggest it on our posters. For some folks a film where no life hangs in the balance is simply not worth watching.

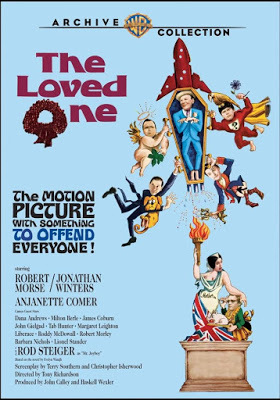

There are even movies where the phenomenon of death and dying becomes its own sort of dark comedy. Quentin Tarantino films like Pulp Fiction know how to walk the fine line between death as tragic and death as funny. But I’m thinking more of the 1971 cult favorite, Harold and Maude, in which an unhappy young man plays at suicide and a wise elderly woman shows him the meaning of life—and death. (They meet because both have the hobby of attending funerals.) And I’m particularly thinking of The Loved One , the outrageous 1965 satire (based on Evelyn Waugh’s novel) of Southern California’s extravagant funeral industry Even a simple listing of the cast of supporting characters—Jonathan Winters, Milton Berle, John Gielgud, Tab Hunter, and Liberace—hints at the skewed perspective in this film. It has just had a major fiftieth-anniversary showing at Hollywood’s Egyptian Theatre, sponsored by the American Cinematheque along with the Los Angeles Conservancy’s committee on modernist architecture, which appreciates how this film features L.A.’s urban landscape on-screen.

It’s all too easy to think about dying these days. But I’ve also been giving some thought to conventional funerals after attending a simple but dignified send-off for a friend’s elderly mother. It took place at Hillside Memorial Park, a freeway-close cemetery that many Angelenos spot on their way to Los Angeles International Airport. What first catches the eye is a lofty cupola and fountain dedicated to the memory of Al Jolson. There’s also a statue of Jolson down on one knee in a characteristic pose. It’s all very Hollywood, which is apt because many stars of Jewish Hollywood are buried here. Hillside dates from the era where Jews, even famous ones, weren’t welcome in mainstream cemeteries, like the legendary Forest Lawn. At Hillside they’re buried in style, with many of the most celebrated interred inside a massive mausoleum, complete with marble benches and stained glass windows. On a quick stroll I saw the final resting places of comedians Eddie Cantor, George Jessel, and Jack Benny (who, despite his tightwad reputation, rests in an imposing crypt). There are younger celebrities too. One who surprised me was David Janssen, known for TV’s The Fugitive. Who knew?

Al Jolson Memorial, Hillside Memorial Park

Al Jolson Memorial, Hillside Memorial Park Al Jolson Statue

Al Jolson Statue

Published on December 08, 2015 11:42

Beverly in Movieland

I write twice weekly, covering topics relating to movies, moviemaking, and growing up Hollywood-adjacent. I believe that movies can change lives, and I'm always happy to hear from readers who'd like t

I write twice weekly, covering topics relating to movies, moviemaking, and growing up Hollywood-adjacent. I believe that movies can change lives, and I'm always happy to hear from readers who'd like to discuss that point.

...more

- Beverly Gray's profile

- 10 followers