Beverly Gray's Blog: Beverly in Movieland, page 102

February 12, 2016

“I Love Lucy” Loved Mary, And So Did the Rest of Us

With Valentine’s Day looming, it seems appropriate to remember one of TV’s great domestic comedies, I Love Lucy. As all of us know, the course of true love never did run smooth for Lucille Ball and Desi Arnaz. They may have created a TV empire, but (thanks at least in part to Desi’s chronic philandering) they didn’t manage to make a go of marriage.

Things may not have worked out between Lucy and Desi, but throughout much of her adult life Lucy had the benefit of a great, supportive friendship with one of Hollywood’s most memorable character actresses, Mary Wickes. You may not know her name, but I’m betting the face is familiar. That’s why my colleague Steve Taravella has called his fascinating 2013 biography, Mary Wickes: I Know I’ve Seen That Face Before.

Mary Wickes, born Mary Isabella Wickenhauser (1910-1995) was a tall, lanky, stern-looking Midwesterner with a flair for comedy. After earning guffaws in the Broadway production of The Man Who Came to Dinner, she made the trip to Hollywood to reprise her role, that of a starchy, indignant nurse nicknamed “Miss Bedpan.” Beginning in the 1930s, she played many nurses, housekeepers, and nuns (notably in 1992’s Sister Act). She also frequently took on the role of a man-crazy spinster, though lovers of screen musicals may remember her as part of Mrs. Eulalie McKechnie Shinn’s loyal entourage of Iowa housewives in The Music Man.

In the early days of television, Wickes took pride in creating the role of Mary Poppins for the famous Studio One. She was often featured on Lucille Ball's various TV shows, most memorably (in an episode of the I Love Lucy series) as a stern ballet instructor forced to put up with Lucy’s shenanigans at the barre. One of her most eccentric showbiz assignments was to pose for the animators at Disney as a live-action model for Cruella de Vil in the original One Hundred and One Dalmatians.

Hollywood is full of talented supporting players, but Taravella’s biography has convinced me that Mary Wickes was one of a kind. In wild and crazy SoCal she lived the life of a Victorian maiden-lady. “Mind your manners” was her favorite adage, and she turned down major roles (such as one in the PG-13 rated Mrs. Doubtfire) when she disapproved of the language in the screenplay. But generally she was devoted to her work, and continued to pursue roles up into her eighties. (As someone who obsessively falsified her birthdate, she tried hard to hide from the studios her actual age.). She was adored by co-workers; Taravella includes a sweet anecdote about her early friendship with young Johnny Whitaker, with whom she co-starred on a Saturday morning TV show called Sigmund and the Sea Monsters. On set, she spent hours patiently tutoring the young boy in her personal dramatic tricks, which included what she called the “butterfly double take.” Years later, she gifted Whitaker and his bride with a butterfly-shaped trivet in memory of the good times they had spent together.

Though Mary Wickes had many friends, most agreed that they rarely got a glimpse of her inner self. In L.A., her closest companion was her mother, a kindly woman who lived with Mary until her death. Especially after losing her mother, Mary devoted much of her free time to her local Episcopal Church and to volunteer work at the area’s hospitals. She also liked to give luncheons and teas at the modest Century City condo she had filled with family heirlooms. Curiously, many of her “gentlemen callers” were gay men. No one is quite clear on whether she fully grasped the implications of that fact.

Here are some glimpses of Early Mary Wickes, notably with Jimmy Durante in The Man Who Came to Dinner. Be warned that the pop music score is annoying in the extreme!

Published on February 12, 2016 13:38

February 9, 2016

Hailing Caesar on the Bridge of Spies

When was the last time you watched a double-feature? It used to be that when you bought your ticket at a neighborhood movie house, you’d get two movies, and maybe a newsreel and a cartoon for good measure. Nowadays, of course, you pay for a single movie, and are hustled out when it’s over. (No sticking around to see something you might have missed because you came in late.)

Super Bowl weekend is a time for out-of-the ordinary behavior. Some people stay home and gorge on bean dip. Others, like my spouse and me, live dangerously at the multiplex. We went to see Bridge of Spies, a worthy Cold War thriller that poses interesting questions about the way we live now. When the lights came on, we realized that we had plenty of time (if we were willing to pay a separate admission fee) to catch the Coen brothers’ latest, an all-star goof called Hail, Caesar!.

Ironically enough, the classy Bridge of Spies can also be considered part of the Coens’ recent output. They were part of the writing team that’s been honored with one of the film’s six Oscar nominations. It was Matt Charman who zeroed in on the story of attorney James Donovan, the private citizen central to the negotiations that traded Soviet spy Rudolf Abel for American U-2 pilot Francis Gary Powers. I’ve heard nothing confirming exactly what additions were made by the Coens, but I suspect that they’re responsible for the screenplay’s verbal wit, as well as for some character details (like Donovan’s nasty cold and Abel’s whimsical stoicism) that make this story crackle to life. Tom Hanks is, of course, his usual Heroic Everyman self, but the picture in many ways belongs to Oscar-nominated British actor Mark Rylance, as a spy who tells nothing, asks for nothing, but is surprisingly lovable nonetheless.

Watching the film’s first half took me back to my childhood when we were all subjected to duck and cover drills, neighbors were building backyard bomb shelters, and the possibility of a nuclear attack by the USSR seemed all too plausible. By contrast, the later scenes—which take place in a divided Berlin—reminded me of my 2015 visit to modern-day Germany. As shown in the film, East Berlin in the early Sixties was a grey-toned place of squalor and rubble. Its citizens were walled off from the West, and machine-gun emplacements were everywhere. Today, by contrast, the reunited city gleams. In 1962, approaching Checkpoint Charlie (as Tom Hanks must do in Bridge of Spies) was serious business. Now, however, Checkpoint Charlie is a tourist destination, with a McDonalds close at hand.

Then, of course, there’s Hail, Caesar!, a movie as blithe and silly as Bridge of Spies is solemn and thoughtful. This shaggy-dog tale of a studio fixer (Josh Brolin) in 1950s Hollywood doesn’t go deep, but it presents a joyous array of movie tropes from the era just before TV and the Youth Movement took over Tinseltown. It’s a Coen brothers valentine to singing cowboys, drawing-room extravaganzas (with Rafe Fiennes as a stiff-upper-life British director trying desperately to teach high style), tap-dancing sailors (Channing Tatum makes like Gene Kelly), and Scarlett Johansson as a tough gal at the center of a Busby Berkeley-style water ballet. (The L.A. Times has a great piece on the Aqualillies, the swim troupe that’s featured in the film.) Then there’s a detour into Blacklist politics, with George Clooney at his dopiest (and dupiest) as the star of a Bible epic who gets kidnapped and brainwashed by a gaggle of Commie screenwriters. Hail, Coens!

Checkpoint Charlie as tourist destination, Berlin, 2015

Checkpoint Charlie as tourist destination, Berlin, 2015

Published on February 09, 2016 13:52

February 5, 2016

Busting Out of Prison, Cinema-Style

We in Southern California don’t seem very good at keeping our felons where they belong. Over the last few weeks, we’ve listened breathlessly to news reports about three accused killers who escaped by rappelling down (via a rope of braided bedsheets) from the roof of an Orange County jail. The fact that they were considered armed and dangerous didn’t make us feel particularly good. I just read a harrowing story about a Vietnamese immigrant cab driver who was commandeered at gunpoint to drive the three around Northern California. At night in a seedy motel room, he listened to them arguing about whether or not to kill him.

They’re back in custody now (phew!), after more than a week of freedom. (Fortunately, the least vicious of the men, the one who ultimately turned himself in to authorities, saw fit to protect the cabbie from his murderous partner in crime.) But around the time they got caught, another inmate escaped, this one from an L.A. lockup. And this morning my newspaper brought me the story of an L.A. County gang member released by accident, even though a murder rap was pending. Oops!

The whole thing, of course, has got me thinking about movies. As we know, there are plenty of great films about dangerous convicts on the lam. Here’s one oldie: The Petrified Forest, starring Humphrey Bogart in a star-making role. It’s not Bogart but Leslie Howard who’s the movie’s hero, the character for whom we’re rooting. Bogart, though mesmerizing, is dangerous and scary: not anyone you’d want to hang out with. (Bogart was to play a similar role in The Desperate Hours, before permanently evolving into a movie good-guy.)

But it occurs to me that over the decades we’ve come to root (at least when we go to the movies) for convicts who manage to break free from their prison cells. Back in the Production Code days, it was a given that lawbreakers had to be punished and escapees had to be tracked down by the forces of law and order. Since then, though, we have developed a curious tendency to view prisoners with sympathy, seeing them as wrongly convicted or as guilty only of minor transgressions that we can somehow excuse. Perhaps it’s a holdover from the turbulent Sixties: today outlaws appeal to us as charismatic anti-heroes. The judges, the wardens, the prison guards: these are the people we mistrust, and we’re glad to see them thwarted in their attempts to bring down men and women who should be roaming free.

Examples? How about The Fugitive, both the TV series and the 1993 film, which focus on the flight of a man (Harrison Ford in the movie) wrongly convicted of his wife’s murder? Then there’s The Rock (1996): its plot is so convoluted as to defy description, but one of its chief heroes (Sean Connery) is the only man ever to escape from the fortress-like island we call Alcatraz. But the best example is The Shawkshank Redemption (1994), a film so well-loved that it was just added to the National Film Registry administered by the Library of Congress because of its cultural and aesthetic significance. Its protagonist (Tim Robbins), has been convicted of a double murder he didn’t commit. He suffers horrors like months of solitary confinement, but ultimately makes a triumphant escape.

Then of course there are all those Roger Corman flicks I worked on – movies with titles like Caged Heat and The Big Bust Out --in which invariably innocent (and scantily clad) young ladies break away from their sadistic captors. But that’s a story for another day.

Published on February 05, 2016 12:09

February 2, 2016

Iowa Stubborn: The Bridges (and Voters) of Madison County

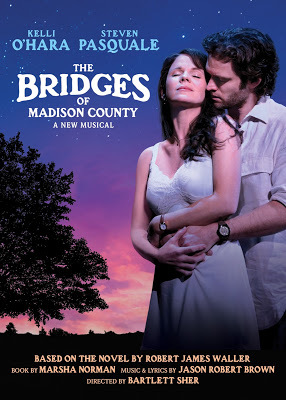

Yesterday, all eyes were on Iowa, as the famous Iowa Caucuses kicked off the 2016 U.S. presidential campaign. As for me, I’ve been thinking about Iowa too. That’s because -- after seeing Jason Robert Brown’s stage musical version of The Bridges of Madison County -- I’ve finally caught up with the celebrated 1995 film. Of course it stars Meryl Streep and Clint Eastwood as the Iowa housewife and the roving photographer who get caught up in a torrid four-day romance when he shows up to snap pictures of the area’s covered bridges. No, I’ve never read the sappy Robert James Waller novel that introduced this saga, and I don’t think I’m ashamed of that fact.

Waller’s novel unfolds from the perspective of the photographer, Robert Kincaid, looking back near the end of his life on a love affair he’s never forgotten. But both film and musical focus primarily on Francesca Johnson, an Italian woman who married an American G.I. at the close of World War II and has since been living a life of quiet desperation on an Iowa farm. Despite the love of her husband and teenaged children, she has never been awakened to true passion until Robert blows into town. Then the question becomes: should she upend her familiar world to follow her bliss?

In the stage version, award-winning playwright Marsha Norman (sensitive to the multiple tugs and pulls on a woman’s existence) surrounds Francesca and Robert’s love story with the doings of family, friends, and neighbors. In a nod to Thornton Wilder’s classic Our Town, she sets their romance in the context of the larger community. This includes two gently bickering oldsters, a neighboring couple living close by. There’s no question in the stage version that the woman (a character named Madge who makes one very slight intrusion into the film) knows what’s going on, and tacitly gives her consent. The play also pays attention to Francesca’s good-guy husband and quibbling kids (off to win a livestock prize at the county fair while there are big doings in the farmhouse bedroom back home). A sense of who these people are gives weight to Francesca’s ultimate decision about her future.

On screen, the affair between Francesca and Robert (told in flashback as her now-grown kids finally learn her secret) seems to take place in a sort of romantic bubble. Perhaps this was deliberate, to heighten the sense of magic isolation between the two. But aside from that one innocent intrusion by Madge, no neighbors are about. We don’t get to learn much about Francesca’s husband and children, the state fair is totally off-screen, and there’s no attempt—as there is on stage—to explain why Francesca felt the urge to leave Italy for marriage in an unknown place. Personally, I would like to have known her worlds (past and present) much better, before buying into her need for love with the proper stranger. The one element of the film that’s not in the stage play is a local woman (seen being denied service in a diner) who has clearly been ostracized for an adulterous romance. We’re eventually told that Francesca will befriend her after Robert’s departure, but not enough is made of the character and her situation to mean much.

The movie, though, does have some things going for it, like amber waves of grain, an appealing score, and – best of all – Meryl Streep. Here she’s dark-haired, olive-skinned, and a completely new person from the actress we know so well. Too bad Clint Eastwood, who produced and directed as well as starring, gave his actor-self top billing.

Published on February 02, 2016 12:02

January 29, 2016

Carol Burnett: TV’s Clown Princess of Parody

One of the new movies opening today is a Marlon Wayans flick called Fifty Shades of Black. It’s not hard to guess which mega-sexy erotic romance it’s spoofing. In recognition of this new release, a Los Angeles Times staff writer has devoted a column to the long Hollywood tradition of making fun of movie hits. Funnyman Stan Laurel was sending up well-known dramatic movies back in the silent era. Bugs Bunny did it decades later. Mel Brooks, of course, has made some of the funniest genre parodies around. Who can forget such Seventies comic gems as Blazing Saddles (spoofing old westerns) and Young Frankenstein (spoofing horror films)? In 1980, the Zucker brothers and Jim Abraham scored with an hilarious parody of disaster movies like Airport. Their film was titled Airplane! Surely you’ve guffawed at it. (And don’t call me Shirley!)

One of the tricky things about a movie parody is that it needs to be able to sustain its comic tone throughout. A spoof can go limp pretty quickly. One of the joys of The Carol Burnett Show was its almost weekly movie parody. These were short, sweet, and hilarious. Of course they were built around the talents of a matchless comedienne who’s being honored this weekend by the Screen Actors Guild with a lifetime achievement award. I can’t think of anyone who deserves it more.

Carol Burnett (now 82 and still active) first won public notice in 1959 for her leading role in Once Upon a Mattress, a musical comedy version of “The Princess and the Pea.” As the gawky and not very delicate Princess Winifred, she was wholly endearing. When the show transferred from Off-Broadway to The Great White Way, a star was born. Broadway led to a featured role on the Garry Moore Show (1959-1962), a TV variety program I remember fondly. She also starred, along with good buddy Julie Andrews, in one of the all-time great TV specials, Julie and Carol at Carnegie Hall

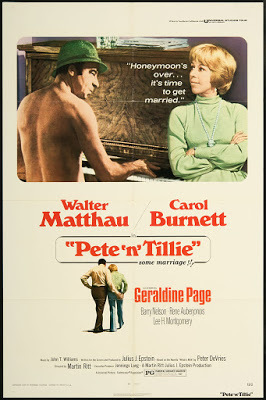

Her movies have ranged from the schmaltzy Pete ‘n’ Tillie (1972, opposite Walter Matthau) to Robert Altman’s wacky A Wedding (1978) to the role of the mean Miss Hannigan in Annie (1982). She copped an Emmy nomination for a rare dramatic role as the grieving mother of a dead soldier in the powerful Friendly Fire (1979).

But of course she’s best known for one of the greatest of all TV variety shows, The Carol Burnett Show (1967-78). As a regular watcher, I loved the blend of music, dance, comic sketches, and the host’s ingratiating personality. In her youth, Burnett had worked as a Hollywood usherette (one who got unceremoniously fired by her boss when she discouraged two movie-goers from entering at the tail-end of Hitchcock’s Strangers on a Train). She has always adored movies, which is why it was only natural for her to parody so many of them on her program. With her stalwart sidekicks (including Harvey Korman, Vicki Lawrence, and, often, Tim Conway) pitching in to help, she delivered devastatingly funny take-offs on movies old and new. I still chuckle at Burnett and Korman in a From Here to Eternity spoof, smooching on the beach and then being doused with a bucket of water. I also remember them as Jenny and Oliver in Love Story, so entranced with one another that they can’t bear to part long enough to answer the doorbell. But most Carol Burnett fans agree that the cream of the crop was her two-part Went With the Wind. Thanks to YouTube for allowing it to live on. All hail the princess of parody—and congratulations!

Published on January 29, 2016 10:53

January 26, 2016

Robert De Niro: A Dirty Grandpa Leaves the Mean Streets Behind

Today I learned that something called Dirty Grandpa had just grossed $11.1 million in its opening weekend, finishing 4th at the box office. Though it did well with ticket-buyers, the critics -- almost without exception -- have hated this movie. Richard Roeper, for one, denied the flick a single star, writing that “If Dirty Grandpa isn’t the worst movie of 2016, I have some serious cinematic torture in my near future.”

Dirty Grandpa (not to be confused with Jackass Presents: Bad Grandpa) is a would-be comedy featuring a foul-mouthed old man whose attitudes are offensive in almost every conceivable way. The gist of the plot is that he kidnaps his uptight grandson (Zac Efron) and drags him on a road trip to Florida. Shockingly, the character is played by the great Robert De Niro, who seems to be making a point of starring in innocuous would-be laugh-fests.

Not that there’s anything wrong with an an actor known for his dramatic skills turning to comedy. It was the great 19th century thespian Edmund Kean who is reputed to have uttered, on his death bed, the immortal show biz maxim, “Dying is easy. Comedy is hard.” Certainly the skill of our favorite comic actors, like Jack Lemmon, Steve Martin, and the late, great Robin Williams, is nothing to sneeze at. And I’ve personally enjoyed De Niro in such comedic films as Meet the Parents and particularly Analyze This, in which—playing a Mafia boss with neuroses—he seemed to be parodying his classic gangster roles of the past.

I have De Niro on the brain right now because of a recent airline trip, on which I attempted to watch his amiable 2015 comedy, The Intern. As seems so often to happen with those seatback television set-ups, the sound wasn’t good, so that I lost a good deal of the dialogue. Then at the midpoint, the transmission failed entirely. No matter—as is true with so many of Nancy Meyers’ film projects, it was easy enough to predict the ending. It seems Anne Hathaway is a brilliant young clothing designer who heads a thriving e-commerce start-up. She’s a workaholic with a cute kid, a shaky marriage, and an intensely hands-on management style. Into her life comes a seventy-year old widower (De Niro) who has traded retirement for a slot in a senior citizen internship program. Of course Hathaway is skeptical of his presence within her trendy loft headquarters. But (although his briefcase and formal suits make him stand out among the company’s hipsters) his business savvy and general common sense turn out to be a godsend, and ultimately set her on the right path.

What’s surprising in The Intern is how convincingly De Niro plays nice. Even a touch of meekness is not beyond his skills. But I’ve got to say that I miss the De Niro of old, the one who was unpredictable and dangerous. I’m talking about the volatile Johnny Boy of Mean Streets, the haunted young Vito Corleone of The Godfather, Part II, the fanatical Travis Bickle of Taxi Driver, the downright scary Max Cady of Cape Fear. Especially for Martin Scorsese, De Niro has played a panoply of mobsters and monsters that movie fans will never forget. More recently, David O. Russell has given him rich roles too, like the father (and obsessive Philadelphia Eagles fan) in Silver Linings Playbook, a film that successfully melded comedy and depth of feeling. I’m glad De Niro feels no inclination to rest on his laurels. But I hope he will confine himself to projects that are worthy of his talent.

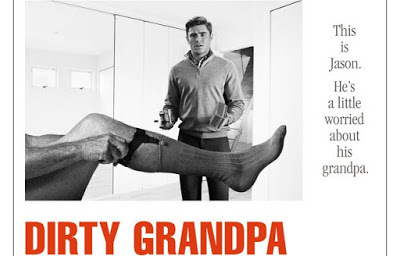

I have no inclination to see this film, but because I'm writing a book on the long-range impact of "The Graduate," this advertising image gave me quite a chuckle.

I have no inclination to see this film, but because I'm writing a book on the long-range impact of "The Graduate," this advertising image gave me quite a chuckle.

Published on January 26, 2016 11:51

January 22, 2016

Doris and Rock Avoid a Trainwreck

I admit I’m not the target demographic, but I just finished watching Trainwreck, the Golden Globe nominee starring and written by today’s comic it-girl, Amy Schumer. As advertised, it’s very raunchy and very funny—not your mother’s romantic comedy, and possibly not yours either, if you’re of the AARP generation.

Amy plays (a character named) Amy, a semi-successful journalist on the staff of a New York-based men’s magazine tellingly called S’Nuff. Having early in life absorbed her father’s mantra that “monogamy isn’t realistic,” she has no use for romantic commitment. But she likes (or rather loves) all the basics: booze, dope, and sex with a series of muscle-bound pretty boys. (Since turnabout is fair play, I really liked the fact that in the film’s many bedroom scenes, Amy remains modestly covered up, while it’s the menfolk whose bare essentials are frequently on view.) What happens when a girl like Amy meets a genuinely nice guy (Bill Hader), who’s also both smart and totally smitten? He can’t match Amy in terms of sexual experience, and she can easily drink him under the table, but there’s the possibility that these two can become one. Since the film is directed by Judd Apatow, who likes to balance raunch with sweetness, the outcome is never truly in doubt. But the journey is a lively one, and a good way to spend a Saturday evening not already occupied with booze, dope, and sex.

Yes, I had fun. But, old-fashioned gal that I am, I couldn’t help remembering back to what romantic comedies meant when I was growing up and learning the rules of engagement between the sexes. Like everyone else, I got a lot of my education in these matters from what I saw on the movie screen. And I certainly don’t recall a heroine of the Amy Schumer ilk.

What I do remember is Doris Day (and, in Sex and the Single Girl, Natalie Wood in full Doris Day mode). Doris (or Natalie) is a smart and sassy working gal. Maybe she is a writer, or a psychologist, or an ad exec. She is fully capable of feeling sexual attraction to a hunky guy of the Rock Hudson ilk. He’s known as a lady-killer, and she comes very close to succumbing to his charms, but is saved by a combination of luck, fate, and her own scruples. (In Sex and the Single Girl, in which Wood plays a virginal version of Helen Gurley Brown, the stud is Tony Curtis. Wood’s character, a psychologist who has written a bestseller about women in the bedroom, talks a good game about modern sexuality, but it’s quite clear her only knowledge of the experience is academic. ) The plot of a movie like Lover Come Back or Pillow Talk or Sex and the Single Girl or The Tender Trap (Debbie Reynolds and Frank Sinatra) always shows how the playboy-type male gets maneuvered into holy matrimony when he surprises himself by falling for the good girl. Even though he might have gotten into her good graces in the first place by way of deception, it’s made clear at the ending that he’s ready to change his ways and wholeheartedly embrace monogamy.

Monogamy—the very thing that Amy’s father railed against. But, at the same time, the thing that we’re hoping for at the end of Trainwreck, once Amy has learned to love herself and unleash her inner cheerleader. (Long story.) Adding to the mix are Tilda Swinton, Daniel Radcliffe, and a whole lot of name athletes. Who knew LeBron James—in the black BFF role—could be so funny?

Published on January 22, 2016 15:57

January 19, 2016

Howard Hughes: From Hell’s Angels to Hercules

Howard Hughes started out with three goals in life. He wanted to be the world’s greatest golfer, the world’s greatest aviator, and the world’s greatest movie producer. Though he made his longest-lasting mark in Southern California as the founder of a major aerospace firm (one that employed my husband for several decades), he had a significant impact on Hollywood both as a movie producer and as the one-time owner of RKO Studios.

Hughes, born in Texas, first entered Hollywood in 1925, at the tender age of 20. Because of his father’s early death he had money, and he also had plenty of chutzpah. He soon produced two silent movies that were financial successes. One, 1928’s Two Arabian Knights, won the first Academy Award for best director of a comedy. In 1930, he spent lavishly ($3.8 million) to shoot a war film that capitalized on his keen interest in aviation. This was Hell’s Angels, starring Jean Harlow along with Ben Lyon and James Hall, who played two brothers enlisting in Britain’s Royal Flying Corps. Hell’s Angels started out as a silent picture but was later converted into a talkie. In the course of a difficult production period, Hughes himself staged the film’s dramatic aerial dogfights. Hell’s Angels marked the first time a motion picture camera shot footage from inside an airplane cockpit. As a director, Hughes was also notorious for waiting for perfect clouds to form. (The film received an Oscar nomination for its striking cinematography.)

Other films produced by Hughes include Scarface (1932), with Paul Muni starring as an Al Capone-type gangster. Because of its level of violence, this film ran afoul of the Hollywood censors, as did the later The Outlaw (1943). The latter gained notoriety when Hughes designed a special metal brassiere for voluptuous star Jane Russell.

Another Hughes exploit had nothing to do with movies. During World War II, the U.S. military had high hopes for the creation of a “flying boat,” an aircraft made out of wood rather than metal, with a large enough capacity to transport troops and equipment across the Atlantic. After much trial and error, Hughes produced what critics nicknamed “The Spruce Goose.” This massive plane—at one time the longest and heaviest aircraft ever built—was not ready until 1947, long after the war was over. It flew only once, and only briefly, with Hughes himself at the controls.

The construction of the Spruce Goose (which Hughes preferred calling the Hercules) required a cavernous hangar on the site of the Hughes industrial complex. The Culver City, California property has sat idle for many years, growing increasingly decrepit. Now, however, the hangar is the centerpiece of an evolving business park known as the Hercules Campus at Playa Vista. Its cavernous interior was used in the filming of Independence Day and Titanic.Recently it was leased by Google, and creative plans are afoot. The surrounding buildings also house high-tech tenants, like the video game firm Konami. The new headquarters of YouTube is also onsite: it boasts a huge outdoor screening facility as well as spectacular video-making equipment. If your YouTube channel has 10,000 subscribers, you too can come to Culver City, dress up in a crazy costume, and make a movie.

Somehow, I think Howard Hughes would be pleased. (I wonder if he’d also be pleased to know that he himself was the star character in two major Hollywood films. In The Aviator he was young, virile, and played by Di Caprio. In Melvin and Howard, he was impersonated by a scruffy Jason Robards as a crazy old coot in the desert. )

Published on January 19, 2016 12:24

January 15, 2016

Black Roles Matter: Denzel Washington

Today, January 15, would have been the 87thbirthday of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. So it’s a special day, and one on which it seems appropriate to salute the contributions of African-Americans to the film industry. I’m writing this a few days in advance, so I don’t know what’s going to pop up in terms of Oscar nominations. Let’s hope we don’t see a repeat of last year’s #OscarsSoWhite Twitter meme. In light of the fact that the big 2015 snubs included one for David Oyelowo’s impressive portrayal of Dr. King himself in Selma, it’s fair to say that anything can happen.

Today, January 15, would have been the 87thbirthday of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. So it’s a special day, and one on which it seems appropriate to salute the contributions of African-Americans to the film industry. I’m writing this a few days in advance, so I don’t know what’s going to pop up in terms of Oscar nominations. Let’s hope we don’t see a repeat of last year’s #OscarsSoWhite Twitter meme. In light of the fact that the big 2015 snubs included one for David Oyelowo’s impressive portrayal of Dr. King himself in Selma, it’s fair to say that anything can happen. Not that race is supposed to factor into a selection of the year’s best performances. (It would be pretty grotesque if we established a quota systems ensuring “fair” distribution of awards in terms of color.) But given the wealth of popular and critically acclaimed movies featuring Black actors that came out in 2015 (among them Creed, Concussion, Straight Outta Compton¸ and Beasts of No Nation), I’m hoping that at least one qualified Black actor or actress shows up on the list of acting nominees. Truthfully, a Black male nominee is much more likely. Pity the poor Black actresses who haven’t seemed to have much in the way of interesting roles in the past year, except on television. (Taraji, you go, girl!) But I would personally vote for Samuel L. Jackson in just about anything, maybe including Snakes on a Plane.

The Golden Globe folks, those jolly members of the foreign press corps who always put on a wild and crazy TV broadcast, this year nominated in the motion picture categories two Black performers, Will Smith for Concussion and Idris Elba for his powerful supporting role in Beasts of No Nation. Neither won, but both were on the ballot. And the Foreign Press gave its annual Cecil B. DeMille Award to an African-American icon, Denzel Washington.

Washington, who made the leap to fame and fortune in the 1980s, has always been regarded as an heir apparent to the great Sidney Poitier. Poitier, of course, made his mark in the Fifties and Sixties. I’ll never forget my family’s excitement when in 1964 Poitier became the first African-American ever to win a Best Actor Oscar, for his charming role in Lilies of the Field. Then in 1967 he scored a rare Trifecta, releasing three films--To Sir, With Love; In the Heat of the Night, and Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner—that spoke earnestly to questions of race while making Poitier the world’s top box office star. Poitier was hugely respected, but his tragedy as an actor was that (understandably, in that turbulent era) he could never permit himself to play anything but heroic roles.

Denzel Washington, like Poitier, seems to be made for heroics, and many of his best parts take advantage of his natural nobility. He won his first Oscar in 1989 for his portrayal of an ex-slave who becomes a soldier in the Civil War drama, Glory. He played a mighty leader in Malcolm X, and a gutsy attorney defending a man with AIDS in Philadelphia. But his Best Actor Oscar came in 2002, for tackling a meaty role that Poitier would never have touched, that of a corrupt cop in Training Day. Ironically, on the same night that he won the statuette, Poitier himself received from the Academy an honorary award “for his extraordinary performances and unique presence on the screen and for representing the industry with dignity, style and intelligence.”

The same could be said about Denzel Washington, a man who does Hollywood proud.

Published on January 15, 2016 12:14

January 12, 2016

"Carol": Bringing a Fantasy to Life

Though I admire Todd Haynes’ carefully modulated brand of filmmaking, I can’t say that I’m a big fan of his current film, Carol. Frankly, although I thought the two central characters in this Lesbian love story were absolutely beautiful to look at, I found myself not all that interested in their passion. Perhaps that shows the limitations of my own sexuality. Listening to a Fresh Air interview with Haynes and screenwriter Phyllis Nagy (who has just been nominated for a Writers’ Guild award for her adaptation of the Patricia Highsmith novel), I realized that they are part of a world I have personally not entered.

Patricia Highsmith, as readers of her fiction are well aware, was best known for psychological thrillers marked by a homoerotic subtext. Her Strangers on a Train was adapted into one of Alfred Hitchcock’s best works, and her Ripley novels have been filmed many times, notably in 1999’s The Talented Mr. Ripley, with Matt Damon in the title role. Curiously, Highsmith was a gay woman who vastly preferred the company of men. But she had an experience as a young shop clerk that led directly into the writing of the pseudonymous novel The Price of Salt, from which Carol is adapted.

It seems Highsmith was working at Bloomingdale’s, trying to earn money to finance her sessions with a therapist. Suddenly she looked up and noticed a customer, whom she later described as “a Hitchcock blonde with a heart of ice.” Absolutely nothing happened. But she replicated the scene, in a sense, when writing The Price of Salt, turning herself into the innocent young woman (played by Rooney Mara in the film) who encounters the love of her life when the elegant Carol comes up to her department store sales counter to buy a Christmas gift.

This fascinating anecdote comes from Phyllis Nagy, who met and befriended a much older Highsmith (by then a famous author) when she was a very young woman in a lowly position at the New York Times. The fact that Nagy is also gay might seem like the source of a natural bond between the two women. But the truth is slightly more complicated. Highsmith at that point in her life was known for aggressively chasing after younger women. One day, when she and Nagy were lunching, she pulled out an old-fashioned wallet and unfurled a series of plastic photo-sleeves. Each one contained a shot of a young woman in skimpy S&M style attire (Nagy compares these photos to Charlotte Rampling’s wardrobe in The Night Porter). Highsmith queried, “I don’t suppose? . . .” But it was plain to both of them that Nagy was definitely not the type. They were, and remained, simply friends.

As a gay woman, Nagy was determined to get at the truth of love between females in her Carol screenplay. She didn’t want to show anyone wallowing in guilt; she did want to show real conversation between women in love. As a gay man, Todd Haynes respected her script and brought to it his own feelings about passion. For whatever reason, the connection between Carol and Therese just didn’t strike me as terribly interesting. (I did not feel the same way about the two male lovers in Brokeback Mountain. Maybe an analyst could explain why.)

At any rate, I love the story about Highsmith turning a very brief encounter into a fantasy, then making it a novel. Curiously, the same thing happened to a young man named Charles Webb. He saw a sexy older woman playing cards in his parents’ living room. Then he wrote The Graduate.

Published on January 12, 2016 11:40

Beverly in Movieland

I write twice weekly, covering topics relating to movies, moviemaking, and growing up Hollywood-adjacent. I believe that movies can change lives, and I'm always happy to hear from readers who'd like t

I write twice weekly, covering topics relating to movies, moviemaking, and growing up Hollywood-adjacent. I believe that movies can change lives, and I'm always happy to hear from readers who'd like to discuss that point.

...more

- Beverly Gray's profile

- 10 followers