Beverly Gray's Blog: Beverly in Movieland, page 101

March 18, 2016

The Family Sinatra; The Family Gershwin

The sudden death of Frank Sinatra Jr., only son of The Voice, at the age of 72 reminds me that there’s a long tradition of showbiz kids capitalizing on their famous parents’ accomplishments. Sometimes the younger generation actually has the chops to burnish the old legend and create a new one. The obvious example is Natalie Cole, who was an outstanding singer in her own right, and even re-introduced her father’s legacy to a new generation, via the beyond-the-grave father/daughter duet on “Unforgettable.”

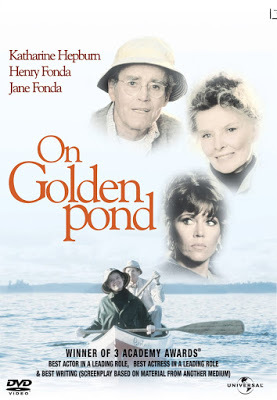

The sudden death of Frank Sinatra Jr., only son of The Voice, at the age of 72 reminds me that there’s a long tradition of showbiz kids capitalizing on their famous parents’ accomplishments. Sometimes the younger generation actually has the chops to burnish the old legend and create a new one. The obvious example is Natalie Cole, who was an outstanding singer in her own right, and even re-introduced her father’s legacy to a new generation, via the beyond-the-grave father/daughter duet on “Unforgettable.” Among actors, there have been some serious acting dynasties. Take Lloyd Bridges, who spawned the gifted Beau and Jeff. And, of course, there are the Fondas: Henry, Peter, and Jane. Jane, who had long had a strained relationship with her cantankerous dad, purchased the rights to the play On Golden Pond so that they could play father and daughter in a story that closely mirrored their own interpersonal struggles. The film version won Henry Fonda a long-awaited Oscar for what would turn out to be his very last role. Jane (herself a two-time Oscar recipient) had given him, clearly, a very special gift.

Then there are those other sons, daughters, and assorted kinfolk who get gigs based on family connections or on a physical resemblance to a blood relation who happens to be a celebrity. Such was the lot of Frank Sinatra Jr. Though his older sister Nancy carved out her own identity as a pop singer (“These Boots are Made for Walkin’”), Frank Jr. was mostly known as a would-be Old Blue Eyes clone, trying hard to emulate his father’s inimitable way with a tender ballad or an up-tempo tune. He spent his life touring, bringing nostalgia to nightclubs nationwide. The only time he himself ever made headlines was when, as part of a bizarre plot, he was kidnapped and held for ransom. That happened in 1963, when Frank Jr. was nineteen; the mastermind turned out to be his sister’s high school chum, who seemed to think he’d done nothing wrong, and that the caper would bring the two Franks closer together. (The incident later became the basis for a 2003 TV movie, Stealing Sinatra.)

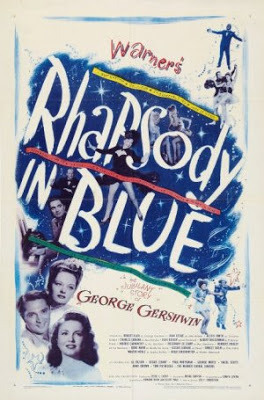

In the Gershwin family, talent seemed to be spread around. George Gershwin was a pianist and composer, juggling classical compositions like An American in Paris with popular scores for the Broadway stage. His Porgy and Bess, once derided, is now considered a major American opera. Many of his tunes showed up in Hollywood musicals, and in later years he made Southern California his home. It was here that he fell mysteriously ill, dying of a brain tumor in 1937, at the tragically early age of 38. (A much fictionalized biopic, Rhapsody in Blue, appeared in 1945, with Robert Alda in the leading role.) Older brother Ira, though sometimes seen as living in George’s shadow, made his own huge contribution to stage and screen. He provided the lyrics for George’s songs, and after George’s death joined with such composers as Harold Arlen, notably for the 1954 Judy Garland version of A Star is Born. Ira lived to be 86.

I didn’t realize until recently that there was also a Gershwin sister, Frances. She was a talented dancer, and she married a classical violinist, Leopold Godowsky. Their daughter, who bills herself as Alexis Gershwin, is a gifted singer who’ll be bringing her uncles’ compositions to a cabaret setting at 8:30 p.m. on Tuesday, March 22. The place is the Catalina Bar & Grill at 6725 West Sunset Blvd., West Hollywood. “Gershwin Sings Gershwin” is the show’s title – it should be unforgettable!

Published on March 18, 2016 11:34

March 15, 2016

Ken Adam: Divine by Design

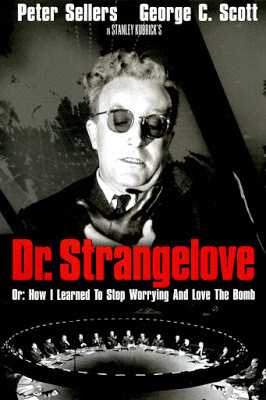

It was thanks to Ken Adam that I got to hold an Oscar in my hands, and exclaim (as everyone does), “It’s so heavy!” Adam, who passed away on March 10 at the age of 95, is best known as the production designer for many of the early James Bond films, as well as for the bravura sets of Stanley Kubrick’s Dr. Strangelove. He loved dreaming up fantastic lairs for bad guys (like Goldfinger’s creepy hideout in Fort Knox), explaining to an interviewer that “to me, designing the villains’ bases was a combination of tongue-in-cheek and showing the power of these megalomaniacs.” None other than Steven Spielberg once told him that his sleek and sinister War Room for Dr. Strangelove was “the best set that's ever been designed.”

Slightly later in his career, Adam turned down the chance to work with Kubrick again on 2001. But they were to reunite for Barry Lyndon. For that film, Adam’s re-creation of the eighteenth-century English countryside, full of manor houses with elegant drawing-rooms, won him his first Oscar in 1975. (That’s the one that sat on his mantelpiece when I visited his home in Santa Monica Canyon.) He ultimately won a second golden statuette for 1994’s The Madness of King George.

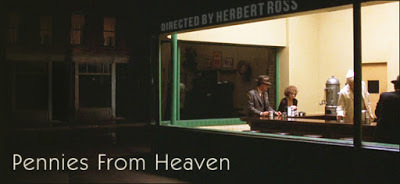

The reason I got to meet Adam was because I had been assigned to write a magazine piece on a bold cinematic experiment called Pennies from Heaven. This 1981 film, directed by Herbert Ross and starring Steve Martin, Bernadette Peters, and Christopher Walken, was based on a British television series. It tells the bittersweet story of a dreamy sheet music salesman in Depression-era Chicago whose fantasies of love and fortune turn into full-blown musical numbers. This blending of realism and make-believe, combined with the opportunity to make the first film musical in twenty-five years on the fabled MGM lot, drew in such talents as cinematographer Gordon Willis (The Godfather) and costume designer Bob Mackie, making his move away from television. Adam himself was billed as the film’s “visual consultant,” and had much to say about the way it should look.

In the original BBC series the shift from reality to fantasy had an amateurish look that was part of its charm. But Adam insisted that this would never be acceptable in an MGM musical. That’s why the design team worked toward total authenticity in the realistic scenes and a lavish sense of completeness in the let’s-pretend sequences. Major sets included a working diner (modeled after Edward Hopper’s famous painting, “Nighthawks”), a bar room, a flop house, a country schoolroom—in which all desks suddenly convert into miniature grand pianos—and the replica of a swank dance floor (costing $40,000) from an Astaire-Rogers duet. One of MGM’s largest soundstages because a white marble bank lobby 50 feet high, while another was transformed into a nearly full-scale reincarnation of the Chicago Loop.

When I met Adam, I did not at first realize that by birth he was not British but German. Much like director Mike Nichols he’d been born in Berlin, but was forced to flee the Nazis at an early age, relocating in London with his family. During World War II, he courageously joined the Royal Air Force as a fighter pilot. After some years in California, he returned to England to live, ultimately being knighted for his service to queen and country, the first production designer so honored. Having made his peace with post-war Germany, he in 2012 handed over his entire archive to the Deutsche Kinemathek, a gracious gesture from a most gracious man..

Published on March 15, 2016 09:38

March 11, 2016

Hannah Arendt, "Son of Saul," and Other Glimpses of a Dark Time

This year’s Oscar for best foreign-language film went to Hungary’s Son of Saul. It’s a movie I didn’t see. I wish I had seen it, but—to be perfectly honest—it’s not something I’ve truly rushed to check out. There are only so many Holocaust movies my overloaded brain can handle. And the makers of Son of Saul have gone out of their way to emphasize that their work (which focuses on an Auschwitz resident forced to lead his fellow Jews to the gas chambers and then later dispose of their remains) is far tougher than any earlier Holocaust film. Clearly, Son of Saul is not a fairytale about survivors or rescuers. In contrast to Schindler’s List, it promises no inspirational message.

I thought about my failure to see Son of Saul while reading a colleague’s impressively researched and written biography of a woman who grappled with the fallout of those terrible years. Anne C. Heller published Hannah Arendt: A Life in Dark Times in 2015, as part of the Icons Series put out by Houghton Mifflin in conjunction with Amazon. (Other books in the series include short works by leading scholars on such wide-ranging cultural figures as Jesus, Stalin, Van Gogh, Alfred Hitchcock, J.D. Salinger, and St. Paul.) Though Amazon was in part responsible for creating the series, the Internet retail giant never quite got around to publicizing it, so these books languish—but are very much worth discovering. Heller’s brief volume introduced me to a woman of almost maddening complexity. I won’t be forgetting her anytime soon.

Hannah Arendt, born into a comfortable German Jewish family in 1906, was a rising young intellectual at the time that the Nazis came to power. In 1933 she managed to leave Germany for Paris, and later New York City. From that vantage point, she watched the decimation of European Jewry. What she saw led her to do heroic work with war refugees; as a political theorist, she also wrote perceptively (in The Origins of Totalitarianism) of the way Nazi concentration camps were used to systematically destroy the human spirit. But many of her longtime friends were dismayed when, reporting on the genocide trial of Adolf Eichmann in Jerusalem in 1963, she at times seemed inclined to blame the Jewish people for their fate, rather than presenting Eichmann as the monster many felt him to be. Arendt’s reasoning was always rigorous, and she certainly never shied away from controversy. It was startling to learn that—late in life—she resumed a close and respectful friendship with Martin Heidegger, a noted German philosopher (and her early lover) who as rector of the University of Freiburg had helped promote the Nazi cause.

Heller’s book on Arendt makes clear that it’s unwise to expect human beings to behave with any degree of consistency. It’s in movies, rather than in real life, that good people and bad people are easily distinguished. When we watch Schindler’s List or Ida or Life is Beautiful or The Pianist, we know where our sympathies should lie. Still, that doesn’t mean that Holocaust films need to be simplistic. It strikes me as particularly important that such films be made in the countries where Nazi atrocities actually happened. One of the triumphs of Son of Saul is that the film fund of Hungary underwrote most of its $1.6 million budget, after Germany, France, and Israel turned down the filmmakers’ request for support. At the Oscars, Son of Saul’s director said it beautifully: “Even in the darkest hour of mankind, there might be a voice within us that allows us to remain human.”

Anne Heller will be only one of the many eminent biographers attending the 2016 conference of BIO, the Biographers International Organization, to be held June 3-5 in Richmond, Virginia. For further information contact BIO. The public is cordially invited.

Published on March 11, 2016 13:48

March 8, 2016

Tricia Hopper: Once a Rider, Now the Writer of “Rodeo Girl”

It was a family tragedy that started Tricia Hopper on the path of becoming a screenwriter. In 1992, when her brother died of AIDS, she wrote a play about a family facing a similar ordeal, and toured it in high schools across Southern California. Then, because she’d always loved movies, she started studying the craft of screenwriting through classes in UCLA Extension’s famous Writers’ Program. (That’s where I had the pleasure of getting to know her.) Always diligent and enthusiastic, Tricia also read how-to books and took workshops, like one offered by screenwriting guru Jeff Kitchen.

Of course, fully half of SoCal’s residents are working on screenplays, as a visit to any local Starbucks will attest. But Tricia has had the good fortune to see one of her projects filmed and released. Rodeo Girl, a wholesome and inspirational script about a teenaged girl, her horse, and her estranged father was bought and produced by Vertical Entertainment. The production values aren’t all that Tricia would have wished for, but she’s a professional screenwriter now—and that’s cause for celebration.

Rodeo Girl began as a screenplay by Aletha Rodgers, whom she’d met in Jeff Kitchen’s workshop. When Aletha asked for Tricia’s critique of her work, Tricia found herself drawn into the world of rodeo. They joined forces, meeting three times a week for over a year. Aletha showed her the importance of deeply researching the rodeo world, and she herself contributed the complex father-daughter relationship that adds tension to the proceedings. Once they’d finished, the script started getting optioned. A mere twelve years later (nothing happens quickly in Hollywood), their third option evolved into a deal with Joel Paul Reisig, a producer-director with whom she’d connected online through InkTip. He’d been looking for a horse story with a young girl as a protagonist, and Rodeo Girl nicely filled the bill.

The story of Rodeo Girl takes place in Oklahoma, where young Priscilla (Sophie Bolen) moves past her earlier biases and learns to become a champion barrel racer, but the film was shot in Michigan. Since Tricia wasn’t present on the set, she was later surprised by a number of changes that had been made in her script. Her heroine -- who starts out as an equestrienne in a formal riding habit devoted to the world of show-jumping -- was originally supposed to be English, but the production honchos made her American. They hired a actor of some repute, Kevin Sorbo (Hercules), to play the father character: though his gruff presence in the film is effective, all of his scenes had to be shot in three days, and his salary ate up half the production budget. There was also some tweaking of important plot points, as well as the addition of a romantic interest who (though certainly a good guy) seems a tad too mature for a fourteen-year-old girl.

Some of the changes, including some downplaying of the father-daughter relationship, at first made Tricia cringe, but she’s pleased that the world of bronco-busting and rodeo clowns shows up vividly on screen. Philosophically she insists that “it always feels good to accomplish something you set out to do. We all know how hard it is to get a script made into a movie.” In future, she hopes to have more control over her projects. She’s just finished her first novel, and a hotshot agent wants a look. If the book is successful and Hollywood wants to turn it into a movie, she’ll insist that a gig as its screenwriter will be part of her deal. Way to go, Tricia!

I’m always delighted to put in a plug for the good folks (and great teachers) at UCLA Extension’s Writers’ Program. Courses are available either on the UCLA campus, at several other SoCal locations, or online. There’s a wide array of screenwriting courses to choose from, and spring enrollment is ramping up right now. So what are you waiting for?

Published on March 08, 2016 12:31

March 4, 2016

My Afternoon at the Oscars (picking up where I left off)

When last heard from, Beverly in Movieland was sitting in a grandstand on Hollywood Boulevard, watching the rich and famous glide by. Of course I wondered just what it must feel like to be part of that glittering horde. When I mulled over my experience, three themes came to mind:

When last heard from, Beverly in Movieland was sitting in a grandstand on Hollywood Boulevard, watching the rich and famous glide by. Of course I wondered just what it must feel like to be part of that glittering horde. When I mulled over my experience, three themes came to mind:Security – We all know, alas, that the world’s not as safe as we used to imagine. Something as friendly and commonplace as an office Christmas party can turn into a death trap. And if we all need to think of ourselves as potential targets for the crazies of the earth, how much more precarious is the life of a star? Let’s not forget what happened to John Lennon: there are twisted people out there who seek notoriety (or the chance to link themselves forever with their idols) by way of cold-blooded murder. That’s why all of us nice folks in the bleacher seats had to go through background checks as well as a serious metal detector. I saw lots of security personnel around the red carpet too, and I know that many major L.A. traffic arteries were off-limits, except for the chosen few, to prevent the uninvited from creating a tragedy.

Scrutiny – Long gone are the days when Joanne Woodward could accept her statuette in an Oscar gown she’d made herself. (She won for 1957’s The Three Faces of Eve, and went up to the stage in a strapless green taffeta that she’d designed and sewn over a period of two weeks. Apparently Joan Crawford sniffed with disapproval that Woodward was “setting the cause of Hollywood glamour back 20 years by making her own clothes,” but almost everyone else admired her as a perfect Fifties housewife.) Today, looking glamorous is absolutely required—even for men—and there are scads of famous designers standing by to outfit the major nominees at no charge. One thing about global warming is that none of the women on the red carpet seemed to feel the need for a coat. Instead we saw lots and lots of skin, sometimes more than was aesthetically appealing. Cate Blanchett, fabulous in ruffled aqua with a plunging neckline, clearly knew how to strike the balance between high style and fun. (I suspect she was also trying to separate herself from her tailored Carol image.) The very petite Naomi Watt, on the arm of her spouse Liev Schreiber, shimmered in a strapless blue and purple sheath. Others, I’m afraid, were pooching out of their tight-fighting gowns, either fore or aft. That’s what made Brie Larson’s look so refreshing: she seemed to be happily sauntering to and fro in the meet-and-greet area, having a lovely time without trying overly hard to impress the fashion police.

Of course it was pleasant to see Leonardo, the crowd’s #1 idol, in tailored evening wear, instead of skins and furs. As well as surprise winner Mark Rylance in a jaunty fedora, and the cute-as-a button Jacob Tremblay of Room, everyone’s favorite Oscar mascot. They all had to look their best—even newscasters like Robin Roberts—because such snarky sites as gofugyourself were standing by waiting to kiss and diss.

Diversity – Then there was diversity, the hot topic of the moment. I absolutely agree that movie roles need to be more inclusive and that some people’s stories are not being told. But on the red carpet, VIPs came in all colors, shapes, and sizes. And (on the surface, at least) they all seemed to really like one another. I’m sure there are behind-the-scenes rivalries, but my view of the red carpet showed me a lovefest.

Margaret Robbie, Louis Gossett

Margaret Robbie, Louis Gossett Matt Damon, back from Mars

Matt Damon, back from Mars Gentlemen Prefer Blondes? Naomi Watts, Reese Witherspoon

Gentlemen Prefer Blondes? Naomi Watts, Reese Witherspoon

Leonardo, of course

Leonardo, of course Whoopi Goldberg

Whoopi Goldberg Lady who's a bit too big for her dress

Lady who's a bit too big for her dressPhotos courtesy of Bernie Bienstock

Published on March 04, 2016 10:19

March 1, 2016

My Day at the Oscars

On Sunday, I went to the Oscars. To be honest, I never got anywhere near the interior of the Dolby Theatre. But, thanks to my connections with the new museum being planned by the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences, I was invited to share in the excitement of what’s called “the Oscars fan experience.” A thousand people come from as far away as Canada and even Australia to sit in bleacher seats on Hollywood Blvd. and cheer for their favorite celebrities.

There are, I learned, many ways to be included in this exclusive group. Some of my fellow bench-warmers were chosen because they subscribe to People magazine. Some got the nod through the Kelly and Michaelprogram. Others won a lottery on the Academy’s website, www.oscars.org.. If you’re among the chosen few, you submit to an online security check, and promise to follow some simple rules. It’s all remarkably well organized. When you arrive at your designated time, your I.D. is checked and you’re politely escorted through metal detectors. (Long gone are the days when you could just show up and mill around Hollywood’s sidewalks, waiting for the Beautiful People to arrive.)

Some entry appointments were for as early as 8 a.m. Luckily I got to sleep in, because I only had to show up at 10. I received my essential photo ID badge, and was handed a huge goodie-bag full of semi-useful stuff. Oscar nominees notoriously receive thousands of dollars worth of coupons for such things as plastic surgery, a so-called vampire facelift, and (ahem) adult toys. My bag was a bit tamer: it contained a seat cushion, a copy of People, some Dove soap, an official T-shirt, and assorted granola bars. Since it would be hours before anyone trod the red carpet, our hosts had provided us with food and entertainment. For breakfast: Coffee Bean beverages and our choice of breakfast rolls. Later there’d be a box lunch and as much Coca-Cola as we could guzzle. There were also several activities to choose from, including a wacky photo booth (complete with props), and a popular hair-styling station, where professionals were on hand to help us look beautiful. We could also wait in line to have our auras read, whatever that means.

By noon we were all squeezed into our assigned seats, waiting impatiently for the real excitement to begin. A roving MC tried hard to jolly us along, eliciting information about who’d sat in the bleachers before (one woman in chartreuse was in her 21st year) and drumming up reasons for us to cheer: “Look—there’s Al Roker!” He also tried hard to build our enthusiasm for the corps of journalists who’d come from all over the world to cover this event. Oscar chef Wolfgang Puck strolled by, surrounded by his white-coated kitchen minions. They tossed Oscar-shaped cookies to the crowd, which certainly fueled our enthusiasm. Quipped a tart-tongued woman in the row ahead of me, “There’s nothing more exciting than planned spontaneity.”

Finally, around 4 p.m., we started to see major stars, most of them wonderfully dressed. Some were persuaded to stop and chat with our MC host, but most of the big nominees rushed quickly past, with a smile and a wave to us in the cheap seats. I saw a lot of famous faces: Matt Damon, Cate Blanchett, Mark Ruffalo, Steven Spielberg, Charlize Theron, Lady Gaga. But for my fellow fans, nothing matched the excitement of the arrival of Leonardo DiCaprio. And then, with the show about to start, Jennifer Lawrence made a last-minute scurry up the carpet.

More—much more—to come.

Some photos of the big day, courtesy of Bernie Bienstock:

Hair-styling for Oscar fans

Hair-styling for Oscar fans

Fooling around

Fooling around Chef Wolfgang Puck and entourage

Chef Wolfgang Puck and entourage Charlize Theron, glamour personified

Charlize Theron, glamour personified

Published on March 01, 2016 12:17

February 26, 2016

Room Without a View – or a Gaslight

With the Oscars just around the corner, I recently saw a much-nominated new film, Room, and an real oldie, Gaslight. Darned if they didn’t make a great pairing, with several elements in common. So I’m going to compare and contrast, as my teachers used to say.

Gaslight started as a hit 1938 play by British dramatist Patrick Hamilton. The premise of this period thriller is that a husband who has gotten away with murder tries to convince his young wife of her own insanity so that he can keep on searching for the missing jewels that belonged to his victim. When the play transferred to Broadway, under the title Angel Street, the murderous spouse was played by none other than Vincent Price. A 1940 British film adaptation much admired by critics was suppressed when Hollywood decided to launch its own version.

In 1944 Gaslight became a major M-G-M release, directed by the great George Cukor. It was nominated for seven Oscars, including Best Picture, Best Screenplay, and Best Black-and-White Cinematography. Charles Boyer was nominated for playing the evil Gregory Anton, as was Angela Lansbury (in her film debut) for her role as a cheeky chambermaid with her own reasons for working against the mistress of the house. That fragile young mistress, Paula, was played by Ingrid Bergman, who won her first Oscar for her pains. Cedric Gibbons’ elegant Victorian art direction was also honored by Oscar voters.

To sum up, Gaslight is the story of a clever but sinister man who marries in order to take advantage of his new wife’s ownership of the house where he believes his victim’s jewels are hidden. While making a great show of being solicitous of Paula’s health, he cuts her off from human companionship and undermines her faith in her own sanity. It’s an ugly story, despite its attractive Victorian surroundings, but Room (adapted by Emma Donoghue from her own prize-winning 2010 novel) is far uglier still. Maybe that fact says something about our troubled age.

In Room there’s no marriage, and no pretense. The character played by Brie Larson, known as Ma, is even more trapped than Paula, but it is not psychological wiles that keep her confined. She is a victim of abduction and rape; for seven years she’s been locked by her captor inside a garden shed fitted out with minimal cooking and toilet facilities. She must look to the man she has labeled “Old Nick” for foodstuffs and other bare necessities; in return she must submit to him sexually, night after night. He even toys with her, when she shows any sign of resistance, by cutting off electricity, leaving her in a physically precarious state. Her situation may have made her distraught, but she’s always fully aware of the horrors afflicted upon her.

Of course, what makes all the difference for Ma is the presence of her five-year-old son, Jack, Though born of rape, he is completely and totally hers, and she devotes all the energy she can muster to nurturing, teaching, and protecting him. Both book and film are essentially told from Jack’s perspective, that of a bright child who has never realized there’s a wide world outside of the place he calls Room. The filmmakers’ challenge, brilliantly achieved, is to create an environment as seen through Jack’s eyes, then allow us to look beyond what Jack can grasp to give us a glimpses of his mother’s very adult challenges. In Gaslight, Paula only comes into her own when a visitor from Scotland Yard fortuitously checks out her situation. Ma, though, must solve her problems on her own.

Published on February 26, 2016 12:12

February 23, 2016

Of Bicycles, Venice Beach, and Orion Griffiths . . .

It’s February, so of course I spent my SoCal Sunday riding a bike near the ocean. Believe me, Venice Beach presented itself like a movie set, full of skateboarders, bikers, strollers, vendors, and crazies of all descriptions. Not to mention sun, sand, and tall, skinny palm trees. I could imagine hearing Randy Newman belting it out on the soundtrack: “I love L.A.”

My own town, Santa Monica, has a nifty new Breeze bike-share system I was eager (OK, scared but willing) to try it. Fortunately my husband, the technological brains of the family, helped out. You download an app, then use your mobile phone to unlock one of the sturdy lime-green bikes from its resting place. Since Santa Monica abuts Venice, reaching Venice Beach was a simple matter. I came home feeling good, and with my knees and elbows still intact.

Being me, I spent some of my bike-riding time thinking about movies that feature bicycles. Of course there’s Vittorio De Sica’s post-war Italian neo-realist masterpiece, The Bicycle Thief. In this 1948 film, a bicycle is the key to livelihood of a man from the working class. When his bike is stolen, he and his young son desperately search the streets of Rome to track down the thief. Quite a far cry from my Sunday joyride.

Bicycles are also at the center of an inspirational coming-of-age story set in Bloomington, Indiana. But these aren’t the humble two-wheelers used by workmen to earn their daily bread. Breaking Away (1979) focuses on the sleek bikes that glide along race courses like those in Italy and France. It’s the tale of some appealing young locals who compete against arrogant frat boys at Indiana University’s annual Little 500 bicycle race.

Cycling plays a major role too in The Triplets of Belleville, a wacky French animated film from 2003. In it (to the extent that anything is clear in this surrealistic delight) a Tour de France competitor is kidnapped by some sinister gamblers, only to be saved by his elderly intrepid grandmother and some nightclub singers who have come along for the ride. Ooh la la!

Venice, California, has had its own share of movie close-ups. Its sparkling beaches, seedy alleys, and unconventional lifestyles have appeared in dozens of Hollywood films. Long ago the arcaded streets of Venice were featured in Orson Welles’ A Touch of Evil, standing in for a Mexican border town. But more recently Venice has played itself, in such varied films as The Doors (1991), White Men Can’t Jump (1992), The Big Lebowski (1998), Thirteen (2003). And Lords of Dogtown (2005).

In Venice, anything can happen. This past Sunday, while I was on the Venice boardwalk on my lime-green bicycle, I stumbled upon something that was almost better than a movie, because it unfolded right before my eyes. It was a handsome, hunky young Brit gathering passers-by around him so that he could put on a show. His particular skill was balancing: he could do impressive handstands while perched on teetering platforms high above the crowd. But his #1 talent was working that crowd, keeping up a colorful stream of patter, alternately teasing and cajoling us into paying attention. It was a stellar performance, and I wasn’t surprised to learn that he had Hollywood in his sights. The child of circus performers, he’d come to the U.S. and landed an ensemble role in the recent circus-slanted revival of Broadway’s Pippin. Now he’s in L.A. studying acting and dreaming of his big-screen break. I can’t help with that, but at least I can spread the word. Orion Griffiths, I salute you!

Published on February 23, 2016 16:04

February 19, 2016

Pray for Zika’s Babies

Just when you thought it was safe to get pregnant, along comes the Zika virus. As everyone has read by now, it’s the newest, scariest plague on the planet. The medical research is still not complete, but there’s the possibility that when the disease affects pregnant women, they’ll give birth to babies with microcephaly: abnormally small heads and brains. In some parts of Latin America, where the outbreak is still unchecked, women are being warned not to get pregnant. (In countries where birth control, not to mention abortion, is strongly discouraged, this is doubtless posing interesting social challenges. I just heard that Pope Francis himself accepts contraception under these circumstances.)

But my job is to write about movies, not disease-of-the-week scenarios. So when I hear about the disturbing possibilities posed by Zika, I think back to films that remind us that carrying an unborn baby for nine months can be hazardous to one’s health. The obvious example, of course, is Rosemary’s Baby, which scared the daylights out of most of us back in 1968. I always thought that Ira Levin, the writer of the 1967 novel that engendered Roman Polanski’s film version, had hit upon a brilliant premise. The idea of a problem pregnancy is something that most women can understand on a visceral level. Even the most benign nine-month gestation period has its moments in which the mom-to-be wonders if, in fact, she’s bearing Satan’s spawn.

(There’s a grim irony, of course, in what happened a year later to Polanski’s own unborn baby. He died—about two weeks before his impending birth—along with his mother Sharon Tate, at the hands of Charles Manson’s ominous crew. Not all danger comes from within.)

A 1979 horror film by the very twisted David Cronenberg also makes a comment about pregnancy. I’m thinking of The Brood, a film whose climax is as eerie and disturbing as any I can recall. I’d rather not go into detail, for fear of spoiling the climactic plot twist, but suffice it to say that The Brood dramatically portrays the physically and psychically intimate connection between a mother and her progeny.

Which leads me to a Concorde-New Horizons film to which I contributed, in my position as Roger Corman’s story editor. The Unborn (1991) takes its genuine power from the anxiety that a women can naturally feel when her body has been invaded by a mysteriously evolving creature. Interestingly enough, it was written by two young men , John Brancato and Michael Ferris, who (to fool the union watchdogs at the Writers’ Guild) used as a pseudonym a combination of their middle names, Henry Dominic. These guys were Harvard Lampoon buddies of my Concorde colleague, Rodman Flender, who had finally gotten the opportunity to direct his first feature. It’s the tale of a young married woman (Brooke Adams) who—unable to get pregnant—resorts to experimental in vitrofertilization at the hands of the inevitable mad scientist (the creepy and wonderful James Karen). The pregnancy is painful and difficult, and the birth . . . well, I don’t want to spoil the ending.

Trivia about The Unborn: for this film my friend Rodman cast (Friends’ ) Lisa Kudrow in one of her very first professional roles. And when Roger Corman hired Brooke Adams to write and direct as well as star in a sequel, we struggled with the impossibility of putting this particular child on screen. Eventually, there would be The Unborn II, though it’s only remotely connected to the first film. Leave it to Roger to find a way to save the franchise.

Published on February 19, 2016 09:46

February 16, 2016

A Night at the Opera: Mozart Meets Salvador Dalí in The Magic Flute

I went to the opera this past weekend, trying to absorb a bit of “kulcha.” It was the perfect production for movie-mad me, one that wed the magic of Mozart’s music to some fancy-pants cinematography, in which live performers constantly interacted with animated images of which Salvador Dalí might have been proud. Dalí, the Spanish surrealist with the weirdly upturned mustache, of course tried his own hand at moviemaking. Back in 1929, he and countryman Luis Buñuel collaborated on a short, silent film, Un Chien Andalou, that featured bizarre images like the slicing open of a woman’s eye with a razor blade. Much later, Dalí actually worked with the artists at Walt Disney Animation on a short project, Destino, that was finally finished and released (and Oscar nominated) in 2003, fifteen years after his death.

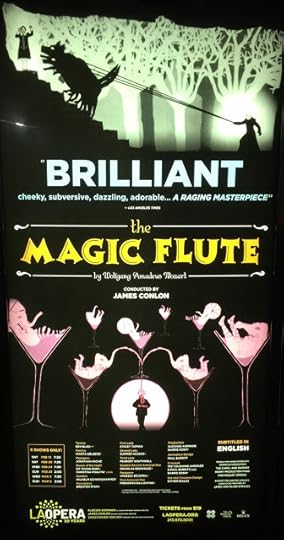

I went to the opera this past weekend, trying to absorb a bit of “kulcha.” It was the perfect production for movie-mad me, one that wed the magic of Mozart’s music to some fancy-pants cinematography, in which live performers constantly interacted with animated images of which Salvador Dalí might have been proud. Dalí, the Spanish surrealist with the weirdly upturned mustache, of course tried his own hand at moviemaking. Back in 1929, he and countryman Luis Buñuel collaborated on a short, silent film, Un Chien Andalou, that featured bizarre images like the slicing open of a woman’s eye with a razor blade. Much later, Dalí actually worked with the artists at Walt Disney Animation on a short project, Destino, that was finally finished and released (and Oscar nominated) in 2003, fifteen years after his death. Mozart’s The Magic Flute is an opera full of mystery and magic: it boasts such neverlandish elements as a giant serpent, a wizard, an antic bird-catcher, and a dangerous Queen of the Night. It’s chockful of symbolism reminiscent of Masonic ritual, and the basic plotline doesn’t make any sort of real sense. In 1975, the great Swedish filmmaker Ingmar Bergman directed a full-length TV version of the opera that was more or less traditional in its staging. More than thirty years later, Kenneth Branagh attempted to give the filmed opera a more 20th century context. But the current production I saw at LA Opera is distinctive in taking its cues from the silent movie era, thanks to the work of a British team (Suzanne Andrade and Paul Barritt) who call themselves 1927, in reference to the year when talking pictures first made their Hollywood debut. Their mandate is to enhance stage productions by way of film. In their version of The Magic Flute, characters seem spawned by silent movies. The heroine, Pamina, has the dark bob of Louise Brooks. The comic bird-catcher Papageno looks and moves a lot like that sad-faced clown, Buster Keaton. The slave Monostatos, with his creepy bald head and elongated fingers, seems borrowed from the classic German horror film, Nosferatu. And the live singers make their entrances and exits through doors in a huge screen on which are projected images both happy (butterflies, fairies, rosy-red hearts) and disturbing (spiders, skulls, flying monkeys, staring eyes, giant hands). There are ominous-looking clocks and giant gears too, for a trendy steampunk effect. The challenge for the performers is to coordinate their movement with the screen images: shooting at the hearts to make them disappear, being chased by huge animated hounds, riding on the back of a very strange pink elephant with human-style legs.

Those elephants, in particular, made me think of the freakiest scene in any Disney movie, the “Pink Elephants on Parade” number from Dumbo (1941), which simulates the effects of alcohol on a small, confused circus animal. (Those Disney animators, no strangers to drink themselves, must have had a ball with that one!) The visual oddities in the stage presentation also are certainly reminiscent of what the Disney folks did with offbeat visuals in the still-remarkable Fantasia (1940).

This Magic Flute also has an undersea segment featuring an Esther Williams parade of giant squids and other strange, watery critters. It brings to mind an animated feature that dates back to the heady (oh so heady!) Sixties. Yellow Submarine , with its parade of weird and wonderful fishies, is still one of my favorite animated films. Whenever I watch it, it makes me feel young again, as did my most recent night at the opera.

Published on February 16, 2016 12:35

Beverly in Movieland

I write twice weekly, covering topics relating to movies, moviemaking, and growing up Hollywood-adjacent. I believe that movies can change lives, and I'm always happy to hear from readers who'd like t

I write twice weekly, covering topics relating to movies, moviemaking, and growing up Hollywood-adjacent. I believe that movies can change lives, and I'm always happy to hear from readers who'd like to discuss that point.

...more

- Beverly Gray's profile

- 10 followers