Beverly Gray's Blog: Beverly in Movieland, page 98

July 1, 2016

Shooting in Baltimore: Cinema in the Charm City

Two weeks ago my travels took me to Baltimore, Maryland, where Roger Corman’s favorite author, Edgar Allan Poe, mysteriously died and was buried. More recently, Baltimore was the site of another mysterious death, that of Freddie Gray, a young African-American who fell into a coma after being transported in a police van. The fact that he was found to have died of spinal cord injuries was, to say the least, suspicious. Fortunately for me, I saw no sign of the civil disturbance that resulted from that episode, though the trials of the six police officers involved still continue.

What I saw instead of public anger was a city proud of its sports teams, its crab cakes, and its distinctive Inner Harbor. Not to mention a few branches of Pitango, which serves the best gelato I’ve ever tasted. (Yum!) Since my visit was brief, I didn’t get to see the famous National Aquarium. Nor did I get more than a glimpse of the spectacularly funky American Visionary Art Museum, with its mirrored exterior walls and oddball exhibits.

But I got to gander at the displays in Baltimore’s Museum of Industry, where the city shows off its role as an industrial pioneer. Baltimore, it turns out, is the home of such standard brands as Domino sugar, Black and Decker tools, Head skis and tennis racquets, and Bromo Seltzer. Way back when, this locale saw the invention (or the major refinement) of the linotype machine, the collapsible umbrella, and the crimped bottle cap.

Then, of course, there’s the role played by Baltimore in showbiz. The city’s quirky reputation has made it a good place to set a drama or a very black comedy. Today it’s best known as the setting of The Wire, the hard-hitting HBO crime drama that unfolded over a period of six years, from 2002 until 2008. Series creator David Simon had been a police reporter for the Baltimore Sun, so he was well acquainted with the city’s darker aspects.

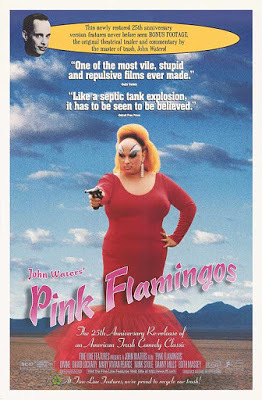

The absolute king of quirk, John Waters, was born in a Baltimore suburb, and still makes the city his home. So did his muse Glenn Milstead, much better known as Divine, who starred in such Baltimore-based Waters flicks as Pink Flamingos. Divine died during an L.A. sojourn, but like Poe he is buried in the place that calls itself Charm City. Though Divine is gone now, Waters sashays on, though it’s been a decade since he’s released a new flick. Every one of the seventeen films he’s directed is set in Baltimore.

Barry Levinson too is a Baltimorean. Though his directing career has been more mainstream and has taken him farther afield, Levinson is responsible for four films set in the Baltimore of his own growing-up years. He made his screen debut with the semi-autobiographical Diner (1982), in which a circle of young males hang out just before one of them is to get married. I remember Diner for its low-key sense of reality, and for introducing me to the talents of Steve Guttenberg, Daniel Stern, Mickey Rourke, Kevin Bacon, Timothy Daly, and Ellen Barkin. Also Baltimore-based are Levinson’s Tin Men (1987), Avalon (1990), and Liberty Heights (1999). Avalon deals with the assimilation of a Jewish immigrant family, and Liberty Heights adds interracial tension into the mix.

A display at the Museum of Industry notes a number of other films shot in the picturesque city: The Accidental Tourist, Clara’s Heart, Broadcast News, and (unlikely though it may seem) Sleepless in Seattle. But I need to close with one of my favorite Audra McDonald songs. I can’t vouch for its message.

Published on July 01, 2016 10:29

June 28, 2016

Hearing the Last of Janet Waldo, aka Judy Jetson (R.I.P.)

The last time I spoke to Janet Waldo on the telephone, she sounded like a sixteen-year-old girl. This seemed remarkable, because she must have been in her 80s at the time. Waldo, who passed recently at the ripe old age of 96, was an actress best known for her youthful voice. Her voice is what earned her the breakthrough role of Corliss Archer, a perky teenager who was the title character in an amiable radio comedy I faintly remember from my childhood.

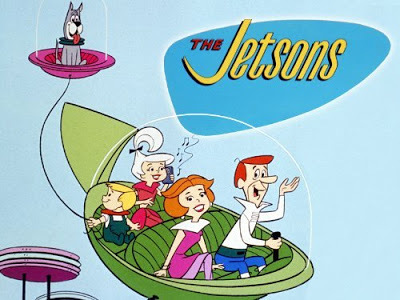

Janet played her share of live-action roles in movies and on television. She’s remembered, for one thing, for appearing on I Love Lucy as a teenaged fan enamored of Ricky Ricardo. (She was 28 at the time.) But she truly made her mark as a voice actress, especially for Hanna-Barbera Productions. It’s hard to believe now how many households tuned in each week to watch The Flintstones, a Hanna-Barbera animated sitcom set in a tongue-in-cheek version of the Pleistocene. The Flintstones, on which Waldo played a battle-axe mother-in-law, was so popular with audiences of all ages that it spawned a similar series with a futuristic slant. This was The Jetsons, and Waldo’s portrayal of rock ‘n’ rolling daughter Judy Jetson was to be her most iconic voice role.

Janet specialized in voicing effervescent young women like race-driver Penelope Pitstop and the lead singer in Josie and the Pussycats. But as a thoroughgoing professional she could handle any voice, from that of a small child to an elderly crone. For an animated TV series based on The Addams Family, she took on six different voices, including those of Morticia and Granny. As she insisted to me when I interviewed her for an article in Performing Arts magazine, “I don’t do voices; I do people.” Still, like most voice actors she was an excellent mimic, one who could respond with ease to a director’s request for a sultry Mae West voice, or a sweet Billie Burke, or a sexy-tough Barbra Streisand. For Fred Flintstone’s mother-in-law, she reached back into movie history and came up with “an exaggerated Marjorie Main.”

I first met Janet when I was working for Roger Corman at New World Pictures. Roger, who had just begun distributing prestigious European art films like Ingmar Bergman’s Cries in Whispers, picked up a charming French-language animated feature set on a faraway planet. The original title was Planète Sauvage, but we re-named it (with a nod to several American sci-fi classics) Fantastic Planet. In order to screen our movie in the heartland, we dubbed it into English. Since I was involved in both casting and the dubbing process, I was lucky to work with voice actors from the golden days of radio. Janet was one of them, and from the start I found her delightful.

While we worked on Fantastic Planet, Ralph Bakshi was heating up Hollywood with R-rated animated features like Fritz the Cat. Of course Roger Corman wanted a piece of that action. Someone came forth with an outrageous cartoon project called Cheap: we all knew Roger would respond in Pavlovian fashion to said title. After much dithering, Cheap became a raunchy piece of animation called Dirty Duck. Sweet, wholesome Janet Waldo was hired to do some of the voices. She told me she had a ball. But she was too embarrassed to put her own name in the credits.

Janet had a long happy marriage to Robert E. Lee, who with writing partner Jerome Lawrence created Broadway and Hollywood favorites like Auntie Mame and Inherit the Wind. He died in 1994, so I guess she’s rejoined him now.

Published on June 28, 2016 12:32

June 24, 2016

Keeping Britain Great: Kings and Queens and Princesses, Oh My!

So—Great Britain is once again at the center of the world. Queen Elizabeth, who turned a hale and hearty 90 on April 21, is now history’s longest-reigning monarch as well the longest-lived ruler of England ever. And, of course, people all over the globe are mesmerized by the outcome of the Brexit vote to leave the European Union.

In thinking about England’s place on the world stage, I can’t help remembering how often the movie industry has turned to British kings and queens for inspiration. The bloody, bawdy Tudors and their circle have been particularly popular on film. The first movie built around the ample figure of Henry VIII dates all the way back to 1911. Charles Laughton won an Oscar for his weighty performance in The Private Life of Henry VIII in 1933. He was thereafter so closely identified with the role that he played Henry once again twenty years later in Young Bess, in which Jean Simmons starred as Henry’s daughter and eventual successor, Elizabeth I. But the actress most identified with the first Queen Elizabeth was the formidable Bette Davis, who played opposite Errol Flynn in The Private Lives of Elizabeth and Essez (1939), and returned to the role in 1955’s The Virgin Queen.

What is there about British royalty that’s so attractive to American audiences? I don’t know, exactly. Maybe it’s a passion for ruffs, cloaks, and farthingales. Maybe it’s the opportunity for swashbuckling, or the fact that a film seems IMPORTANT (if not terribly serious in terms of our day-to-day existence) when there’s royalty involved. Producer Hal Wallis, for one, made quite a career out of epic sagas featuring the British royal family. In 1964 he produced Becket, with Richard Burton as a crony of King Henry II (Peter O’Toole), one who puts his life on the line when he starts taking his religion seriously. As a follow-up to this Oscar-winning hit, Wallis launched 1969’s Anne of The Thousand Days, turning Burton into a love-crazed Henry VIII and pitting him against an Anne Boleyn (Genevieve Bujold) determined to be a queen, not a mistress. Finally, in 1971, he tried for a royal hat-trick. In Mary, Queen of Scots he had two leading British lionesses—Vanessa Redgrave and Glenda Jackson—scratch and claw ferociously in their roles as Mary Stuart and her archenemy, Elizabeth Tudor.

Elizabeth I has continued to show up in more recent films. Her appearance in 1988’s charming Shakespeare in Love is little more than a cameo, but it won Judi Dench (who -- barely 5 feet tall -- looks nothing like the tall, slender Elizabeth of history) a Supporting Actress Oscar. In 1998 Cate Blanchett won acclaim, if not an Oscar, for Elizabeth, a fascinating film about the making of a very young monarch. (There was also a 2007 sequel.)

Though films about the Tudors are still being made, in the twentieth-first century several hits have focused more on what it’s like to be a British monarch coping with the modern world. The top Oscar-winner for 2010 was The King’s Speech, in which a reluctant George VI (Colin Firth) must assume the throne because of his brother’s abdication. His struggle to conquer a bad stutter in order to make himself heard by the nation in the dark days of World War II is for me truly memorable. And of course there’s 2006’s The Queen, in which Helen Mirren as Elizabeth II faces both the perks and the challenges of her office, including the death of Princess Diana, thereby proving that she’s by no means an anachronism. All hail!

Published on June 24, 2016 11:35

June 21, 2016

Helen Scott: Chère Amie de Truffaut

Though my kinfolk are good people, one and all, I can’t think of any who changed the course of history or contributed to any major artistic achievement. But my journalist-colleague Lisa Reswick has legitimate bragging rights about an aunt who helped nurture the French film industry of the Sixties. And it’s partly thanks to that aunt, Helen Scott, that the great Bonnie and Clyde got made.

Let’s start at the beginning. Helen Scott, though New York-born in 1915, was raised in Paris, where her father served as a correspondent for the Associated Press. To the end of her days, it was her flawless knowledge of the French language, along with her feisty personality, that made all the difference. Her 1987 obit in the New York Times fills in details of her early professional life as a political journalist: “During World War II, Mrs. Scott broadcast for the Free French from Brazzaville, the Congo. After the war, she served as press attaché for Chief Justice Robert Jackson at the Nuremberg Trials of German war criminals. Later, she became a senior editor at the United Nations.” Throughout these experiences she displayed the deep sympathy for the underdog that had once led her (back in the economically dismal 1930s) to work as a Communist organizer.

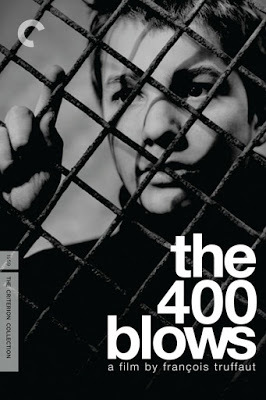

In the McCarthy era, her past political leanings threatened her livelihood. But a New York-based job at the French Film Office proved her salvation. Through her position she became involved with many of the leading lights of the French New Wave. In 1959 she came to know young French filmmaker François Truffaut, who was visiting the U.S. in conjunction with the release of his first directorial feature, The 400 Blows. The two became close friends and colleagues, exchanging heartfelt letters for many years. When in 1966 he shot an English-language film adaptation of Ray Bradbury’s Fahrenheit 451, she served as an uncredited assistant. She was also the interpreter during the 1962 interviews between Truffaut and Alfred Hitchcock that were later turned into a classic film book.

The relationship between Truffaut and the much older Scott was explored by Lisa Reswick’s daughter, Lillie Fleshler, who used their correspondence as a springboard for her senior thesis in Cinema Production at Ithaca College. Her short film (which was screened as part of a Truffaut retrospective at the Cinémathèque Française in 2014) spotlights the letters, while also incorporating footage of an interview with Truffaut’s former wife, Madeleine Morgenstern. Morgenstern speaks with great affection of Helen and also of the man whom they both—in their way—deeply loved. The two women agreed that Truffaut was something of a brat, who “didn’t know what he wanted, wanted what he couldn’t have.” They both realized that he “needed love and acceptance from everybody, and especially women.” He was not, in other words, the ideal husband, and Helen felt the sadness of this realization, on Madeleine’s behalf.

Her own closeness to Truffaut led to an unexpected cinematic coup. Would-be screenwriter Robert Benton and his writing partner David Newman idolized Truffaut, and hoped to interest him in their original script, Bonnie and Clyde. It was Helen who helped them connect with Truffaut, who admired their work but had no time to pursue the project. Through Truffaut the screenplay made its way to Jean-Luc Godard, who was equally enthusiastic—and considered himself available. So Bonnie and Clyde could have been a French production. Of course, it ultimately wasn’t, but Helen Scott remains part of the history behind the Arthur Penn masterwork that turned Benton and Newman from screenwriting newbies into Hollywood insiders..

Published on June 21, 2016 09:00

June 17, 2016

"China Dolls": There’s No Business Like Show Business

Funny – she doesn’t look Chinese. Lisa See, whose mother is novelist Carolyn See, has explained her unusual history on her father’s side in On Gold Mountain: The One-Hundred-Year Odyssey of My Chinese American Family (1996). Through a complex set of circumstances, beginning when her Chinese immigrant great-grandfather married an outcast white woman, See inherited a strong interest in the Chinese side of her ancestry. That interest has led her to write a number of bestselling novels set in China, including Shanghai Girls and Snow Flower and the Secret Fan. Her latest is

China Dolls

, which in telling the intertwined story of three Asian-American performers in the era just before and just after World War II graphically delineates the role of the Chinese woman on the American stage and screen.

Funny – she doesn’t look Chinese. Lisa See, whose mother is novelist Carolyn See, has explained her unusual history on her father’s side in On Gold Mountain: The One-Hundred-Year Odyssey of My Chinese American Family (1996). Through a complex set of circumstances, beginning when her Chinese immigrant great-grandfather married an outcast white woman, See inherited a strong interest in the Chinese side of her ancestry. That interest has led her to write a number of bestselling novels set in China, including Shanghai Girls and Snow Flower and the Secret Fan. Her latest is

China Dolls

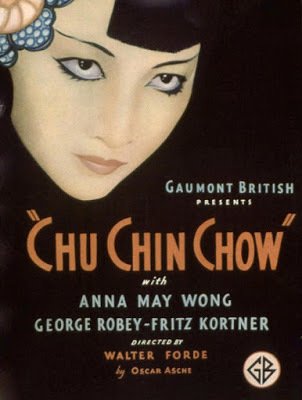

, which in telling the intertwined story of three Asian-American performers in the era just before and just after World War II graphically delineates the role of the Chinese woman on the American stage and screen.The three heroines of See’s novel, who take turns narrating the story, become nightclub performers for very different reasons. Grace, a Chinese-American raised in a small town in the Midwest, has always felt inferior to her Anglo classmates. The movies are her refuge, but at first she sees no opportunities for women with Asian faces, aside from the Dragon Lady roles of Anna May Wong. Then she discovers a subculture of Chinese performers who imitate their All-American peers, billing themselves as the Chinese Fred and Ginger Rogers, and even (as a spicy attraction at San Francisco’s Golden Gate International Exposition) the Chinese Sally Rand. Eventually Grace and the novel's other main characters—who have their own reasons to overcome their past—find jobs as dancers at a new San Francisco Chinatown nightclub called The Forbidden City.

The allure of this nightclub, which actually did flourish in pre-war San Francisco, lay in its titillation of mostly-white patrons with a floorshow combining the exotic with the familiar. The lavish décor was straight out of a fantasy opium den, and the all-Asian performance troupe delighted the customers with professionalism and sex appeal. One passage from the novel, in which the nightclub’s dancers are filmed on a local beach for a newsreel, gives some indication of the cross-cultural forces at play: “We lined up on the sand, wearing big headdresses that tinkled and glittered with every movement, and embroidered Chinese opera gowns with long water sleeves made of the lightest silk, which draped over our hands a good twelve inches. Our feet dragged in the sand, but our water sleeves floated and blew in the ocean breeze. We sidestepped until we were behind a coromandel screen set up incongruously on the sand to discard our headdresses and gowns, and toss them toward the camera in a manner bound to provoke good-natured chuckles. The music changed to a jitterbug. Now in bathing suits, we swung out from behind the screen. ‘Well, well, well,’ the announcer intoned with proper surprise. ‘What would Confucius say?’”

The WASP enthusiasm for ersatz Oriental culture (evenings at the nightclub conclude with a spirited “Chinaconga” line) comes to a quick end with the bombing of Pearl Harbor and the entry of the U.S. into the war. See’s story line doesn’t overlook the situation of Japanese-American performers who try to evade relocation orders by masquerading as Chinese Americans. One such, historically, was funnyman Goro Suzuki, who changed his name to Jack Soo and went on to a successful Hollywood career on sitcoms like Barney Miller. As for See’s characters, they eventually learn to make ends meet by going out on the “chop suey circuit” of novelty nightclub acts. My favorite part of China Dolls was learning what American showbiz meant to perceived “lotus flowers” with roots in the Far East.

Published on June 17, 2016 09:00

June 14, 2016

Women Under Attack: Theresa Saldana and Some Others

Somehow it’s fitting that, at the time that a particularly ugly campus rape (and its prosecution) is making news across America, media sources are announcing the death of actress Theresa Saldana. Saldana, who died of an unnamed illness at age 61, was a working actress celebrated for her role in Martin Scorsese’s Raging Bull and for a number of TV appearances. But the public best knew her for surviving an attack by a deranged fan, who traveled from his home in Scotland to track her to her West Hollywood apartment. On the morning of March 15, 1982 he approached her on the sidewalk and stabbed her ten times, only stopping when accosted by a passing bottled-water delivery man. Thankfully she recovered from her wounds, founded an advocacy group to push for stricter anti-stalking laws, and had the fortitude to play herself in a 1984 TV movie titled “Victims for Victims: The Theresa Saldana Story.” Re-enacting the scene of her attack for the cameras must have taken real courage. (Sadly, the story was repeated—with a much more tragic outcome—last week when a finalist on The Voice, singer Christina Grimmie, was killed after a concert in Orlando, apparently by yet another male “fan.”)

It’s not only women who suffer at the hands of stalkers: look at what happened to John Lennon. But women, whether famous or not, are particularly vulnerable. Which reminds me of another death that occurred this past year, that of British actress Adrienne Corri. She may not be well known, particularly in this country, but personally I’ll never forget her. For it was Corri who played a ghastly scene in Stanley Kubrick’s brutal dystopian drama, A Clockwork Orange (released in the U.S. in 1971). In the film, Corri is an affluent housewife, lounging with her husband in an isolated suburban house filled with arty bric-à-brac. Suddenly, the sanctity of their home is violated by protagonist Alex (Malcolm McDowell) and his band of marauding delinquents, known in the parlance of Anthony Burgess’s source-novel as Droogs. As her husband, bound and gagged, is forced to watch, Corri’s character is attacked by the young punks. Her red jumpsuit is sliced away, leaving her naked and vulnerable. Alex then assaults her viciously to the cheery tune of “Singin’ in the Rain,” before ramming her with a phallic-looking piece of object d’art. The scene is staged by Kubrick to be darkly funny. Most of the first-run audience surrounding me at the Grauman’s Chinese Theatre howled with laughter. Personally, in all my days of moviegoing, I have never felt so female, nor so vulnerable.

Why would a woman want to play such a role? The legend is that Corri took the part when another actress refused to go through with it. For her, a role was a role. In the course of her long stage and screen career, she acted in the works of Samuel Beckett, and was directed by legends like Jean Renoir (The River) and David Lean (Doctor Zhivago). Her New York Times obituary describes her as “fearless,” and she was even able to approach a harrowing rape scene with a sense of humor.

But rape, as we keep needing to be reminded, isn’t funny. Jonathan Demme drove home that point in a 1988 film, The Accused. The role of the victim of a brutal gang rape in a pool hall won Jodie Foster her first Oscar. The film forcefully argues against the “blame-the-victim” mentality that still shows up in too many courtrooms. Still, it’s sad that Hollywood actresses are so often rewarded for parts that trade on their characters’ victimization.

Published on June 14, 2016 08:30

June 10, 2016

Muhammad Ali and Katherine Dunne: Two Who Are Down for the Count

The death of Muhammad Ali has made me take a look at what’s sometimes called “the sweet science.” What is there about boxing that so enthralls spectators? Maybe the fact that it’s an up-close-and-personal sport, one in which two well-muscled athletes wearing very little come together in a violent mano à mano in full view of the fans in the ringside seats. Maybe when we watch boxers in dubious battle we’re calling up historic memories of gladiators slugging it out in the Colosseum. Maybe boxing is so brutal, and those who participate in the sport are so vulnerable, that we can’t avert our eyes from what promises to be a kind of human trainwreck.

In any case, the motion picture industry has always loved movies in which much of the action is set in a boxing ring. The tradition, dating back to the 1940s, is that boxing films focus on a champ’s corruptible flesh and even more corruptible moral fiber. It was in 1947 that Body and Soul (written by Abraham Polonsky, directed by Robert Rossen, and starring John Garfield) galvanized audiences by showing how an upstart with pugilistic talent can become the fallguy of unscrupulous operators who see him as their meal ticket. (The story is that legendary cinematographer James Wong Howe donned roller skates and carried a hand-held camera into the ring in order to convey a close-in look at what goes on in a boxing match.)

In 1949, Kirk Douglas achieved stardom as double-crossing boxer Midge Kelly in Champion, the first film produced by the great Stanley Kramer. In a story (based on a Carl Foreman script) that reveals its “hero” as capable of deception, backstabbing, and even rape, Champion makes the point that winners should never be confused with good guys. The same message is reinforced in Martin Scorsese’s Raging Bull, a 1980 biopic of the boxer Jake La Motta that powerfully charts its protagonist’s rise and fall.

Of course not every movie boxer is depicted as ruthless. The 1970 screen adaptation of the Broadway hit, The Great White Hope, uses the real-life story of Jack Johnson to highlight the racial aspects of the boxing world, with the leading character (James Earl Jones) penalized for his color and for daring to love a white woman. In 2005, director Ron Howard made heavyweight champion James J. Braddock (Russell Crowe) a sympathetic figure, one who turns to boxing as his family’s way out of the Depression. And of course there’s Sylvester Stallone’s Rocky, which starting in 1976 made a lovable loser into a figure of blue-collar dignity.

Muhammad Ali himself inspired many documentaries as well as a 2001 biopic starring Will Smith, who had gained Ali’s seal of approval as the only Hollywood actor pretty enough to impersonate him. Most audiences agreed that the dynamism of the real Ali did not fully come across in this fictional look at his boxing career and his gutsy civil rights stance. Ali was simply too remarkable a figure to be captured by someone else’s performance, and it promises to be the videotapes of Ali in action (both fighting and talking) that will be treasured in years to come. While I say goodbye to Ali, I also mourn the loss of author Katherine Dunne, with whom I enjoyed chatting when I was on Roger Corman’s payroll. I hoped she’d write a script for us, but it was not to be. Dunne’s masterpiece was an outrageous circus story, Geek Love , but she also won prizes for her take on boxing. So sorry that she and Ali were not saved by the bell.

Published on June 10, 2016 17:07

June 7, 2016

The Dog Merchants: How Movies Have Got Us Going to the Dogs

Do you love dogs? Then you’ll appreciate the work of my colleague, Kim Kavin, whose career as a journalist and a dog-lover is dedicated to the well-being of canines everywhere. Her latest book is a bold exposé of how dogs are exploited for human gain. The Dog Merchants: Inside the Big Business of Breeders, Pet Stores, and Rescuers was published in May. Now a politician has been compelled, after reading Kim’s book, to introduce an amendment tightening a piece of “pet store puppy mill” legislation that’s pending in the New Jersey state legislature. If the amended law is passed, it should serve as a model for laws in other states.

Like any author, Kim wants to make sure her book is read. That’s why she’s posted on YouTube a series of lively video book trailers intended to warm the hearts of dog lovers everywhere. One called “The Blue-Eyed Mutt” actually went viral, seen by 23,000 people the world over. (See below!) Curiously, the inspiration for Kim’s trailers came from her knowledge of a dog who had conquered Hollywood back in 1923, the very famous Rin Tin Tin. This German Shepherd was an accidental star. He was rescued from a French battlefield at the end of World War I, learned some new American tricks, and found himself in the leading role in a silent epic from Warner Bros., Where the North Begins. So popular was Rin Tin Tin as a screen performer that he starred in 25 films, ultimately saving his home studio from bankruptcy. In the silent era, it was easy to make his appeal universal: his barking needed no translation, and the studio had only to replace the film’s English-language dialogue frames with those in other languages. Kim followed this same logic, filling her trailers with adorable pooches and changing out the text to serve her own evolving needs.

Rin Tin Tin was so popular in his own era that suddenly the German Shepherd became the backyard pet of choice. Fads in dog-breeding continued in later decades, reflecting whatever was popular in local cinemas. In 1961, after Disney released the original animated 101 Dalmatians, suddenly every kid in America wanted a big white dog with black spots. When a live-action version of the film appeared in 2000, the yen for Dalmatians intensified. Something similar happened with Chihuahuas in the late 1990s, on the heels of a series of Taco Bell commercials featuring a particularly ungainly Chihuahua pup. And the sitcom Frasier started a rush on Jack Russell Terriers..

There is, of course, a downside to the public’s waves of enthusiasm for various dog breeds. Those good souls who dedicate themselves to animal rescue know that many families who fall in love with a cute dog at the movies or on TV are not prepared for the challenges of pet-ownership. Unscrupulous breeders are only too happy to pump out supplies of whatever sort of dog is currently in fashion. They’re not bothered by the fact that a number of the dogs they’re selling will be cruelly abandoned by their owners. That’s why, according to Kim, tenderhearted rescuers are resigned to showing up in front of movie theatres with their own dogs in tow, begging parents not to succumb to their kids’ pleading for a real-life carbon-copy of the rambunctious critter they loved on screen. These rescuers, like Pati Dane of Dalmatian Rescue, try hard to explain that dog ownership requires expense and hard work, and that a plush toy dog would probably work better for many kids in the long run..

And that’s something to bark about.

Published on June 07, 2016 10:59

June 1, 2016

It’s a Bird! It’s a Plane! It’s a Superboss! Roger Corman and Some Others

Roger Corman doesn’t often show up in how-to books aimed at the business world. And these aren’t the sorts of books I normally gravitate toward reading. But

Superbosses

, a 2016 publication by Professor Sydney Finkelstein of Dartmouth’s Tuck School of Business, is the exception. Five years ago I was approached by Dr. Finkelstein’s research assistant, who probed me about my Corman years. The published book contains a number of quotes from my biography, Roger Corman: Blood-Sucking Vampires, Flesh-Eating Cockroaches, and Driller Killers. And it makes a good case for Roger as what Finkelstein calls a Superboss, a mogul whose gift for nurturing and inspiring talented underlings has helped to transform an industry. That, of course, has always been a key part of Roger’s legacy: the fact that such major filmmaking talents as Francis Ford Coppola, Martin Scorsese, Jonathan Demme, James Cameron, Gale Anne Hurd, and Ron Howard (as well as countless less famous folk) all got career boosts from him.

Roger Corman doesn’t often show up in how-to books aimed at the business world. And these aren’t the sorts of books I normally gravitate toward reading. But

Superbosses

, a 2016 publication by Professor Sydney Finkelstein of Dartmouth’s Tuck School of Business, is the exception. Five years ago I was approached by Dr. Finkelstein’s research assistant, who probed me about my Corman years. The published book contains a number of quotes from my biography, Roger Corman: Blood-Sucking Vampires, Flesh-Eating Cockroaches, and Driller Killers. And it makes a good case for Roger as what Finkelstein calls a Superboss, a mogul whose gift for nurturing and inspiring talented underlings has helped to transform an industry. That, of course, has always been a key part of Roger’s legacy: the fact that such major filmmaking talents as Francis Ford Coppola, Martin Scorsese, Jonathan Demme, James Cameron, Gale Anne Hurd, and Ron Howard (as well as countless less famous folk) all got career boosts from him. Finkelstein’s book is not primarily about show business. Yes, it surveys the talents spawned by George Lucas (via such enterprises as Lucasfilm, Skywalker Sound, and Industrial Light and Magic). There’s even an extended look at the career of Ben Burrt, who through his involvement with Lucas on the original Star Wars became a pioneer of modern sound design. And Finkelstein also traces the impact of Lorne Michaels, creator and long-time producer of Saturday Night Live, on the scores of comic talents whose lives he’s transformed. (Think of Bill Murray, John Belushi, Gilda Radner, Mike Myers, Chris Rock, Tina Fey . . . and the list goes on.)

But Finkelstein also delves into other kinds of superbosses. There’s Alice Waters, whose emphasis on simple cooking with fresh local ingredients at Berkeley’s Chez Panisse has revolutionized the restaurant industry by way of chefs inspired by her methods. There’s Ralph Lauren in the world of fashion. There’s Jay Chiat, advertising guru, and journalist Gene Roberts, a beloved editor at the Philadelphia Inquirer. Not to mention a good many figures from the business world. Each, in his or her way, has brought forth whole generations of protégés who continue in the master’s footsteps, though not without contributing their own unique twists.

Finkelstein makes clear that superbosses are not all alike. In terms of personality, he divides them into three categories: the Innovators, the Nurturers, and the Glorious Bastards. His prime example in the latter category is Larry Ellison, of Silicon Valley’s Oracle. Ellison, according to those who worked for him, was not always easy to take. And he could never be accused of selflessness. Roger Corman, too, seems to fit into this group. Former employees will agree that they didn’t always like him, but they always respected him . . . and his example prodded them to do their very best, often while working at tasks that seemed impossible.

Reading Finkelstein’s book made me think back to my own hiring by Roger at New World Pictures. He personally chose me as his assistant even though I had no filmmaking experience, merely some opinions I’d vented as a campus movie reviewer. He hired me, I believe, not because I fit some formal profile but rather because in conversation we clicked. And once I came on board, he encouraged me to spread my wings. I naturally gravitated toward developing scripts, but he also tried me out as a location scout. I worked on a production, got involved with casting, helped on publicity campaigns, and even oversaw a looping session. I may not have always liked him, but he changed my life. Thanks, Roger!

Will you be anywhere near Richmond, Virginia on Saturday night, June 4 at 8 p.m.? If so, head on over to Hardywood Craft Brewery, 2408 Owenby Lane, where I'll be talking about my Roger Corman life prior to a screening of Death Race 2000, one of the many Corman classics I helped to make. Y'all come!

Published on June 01, 2016 17:31

May 31, 2016

“Waitress” – Take the Toast, Hold the Chicken Salad

The recent passing of Beth Howland, who memorably played the scatterbrained Vera on the TV sitcom Alice, reminded me that the entertainment media are full of female characters who look for love while waiting tables at cafes and diners across our land. Some live with the fact that they’re treated badly; others rise above their circumstances and discover they have talents other serving burgers and chicken-fried steak.

Back in 1970, Five Easy Pieces didn’t portray its waitresses with much kindness. The film, which memorably starred Jack Nicholson as an oil rig worker trying to distance himself from his aristocratic family, paired Nicholson with Karen Black, playing his waitress girlfriend. Not only is Black’s Rayette something of a whiny bimbo but Nicholson also makes a hash of his encounter with a waitress unfortunate enough to tell him (in what is probably the film’s best remembered scene) that he can’t order toast.

In 1974, Martin Scorsese shifted away from his usual mean streets to present an endearing portrait of a waitress in Alice Doesn’t Live Here Anymore. Much of the film’s action takes place in a Tucson diner where a recent widow (Ellen Burstyn) with dreams of becoming a singer works alongside the sassy Flo (Diane Ladd) and the spacey Vera (Valerie Curtin), eventually finding romance with an attractive rancher (Kris Kristofferson) who warms to her and her young son. So appealing was this film that Burstyn won a Best Actress Oscar, and the TV series Alice, starring Linda Lavin and Polly Holliday along with Howland, soon followed.

Most waitress movies seem to take place in the Southwest or in Dixie, but Mystic Pizza (1988) sets its three attractive young servers (including a then-unknown Julia Roberts) in a New England town, adding an ethnic touch to its story of young women looking for love. More typical – and much more morose -- is Allison Anders’ 1992 indie, Gas Food Lodgings, in which a single mom (Brooke Adams) and her two young daughters cope with diner work in a dull desert town.

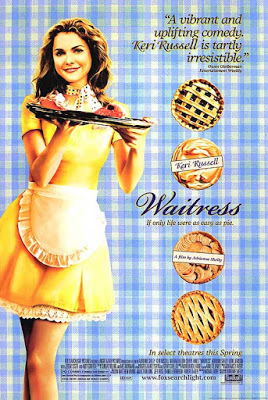

Then there’s Waitress, which in 2007 was an upbeat Sundance favorite, despite the tragic murder of its writer/director Adrienne Shelly (she also appears in the film) just before the film’s debut. The waitress played by Keri Russell is a genius at pie-baking, but she’s also in thrall to a miserably self-centered husband. Then, oops, she realizes she’s pregnant by the jerk to whom she no longer wants to be married. An unexpected affair with her ob/gyn leads her to sort out her priorities, and the end result is an empowered young woman ready and able to make use of her talents.

It’s typical of today’s Broadway that modest movie successes can lead to hit musicals. Waitress, which opened recently with Jessie Mueller in the central role, has just been nominated for four major Tony awards, including best musical and best score (by Sara Bareilles). The cast has a ball with all the pie-baking and jolly Southernisms, and Mueller – along with fellow waitress chums played by feisty Keala Settle and ditsy Kimiko Glenn of Orange is the New Black – sing up a storm. I also enjoyed the presence of veteran Dakin Matthews, whom I interviewed many moons ago, as the crotchety owner of Joe’s Pie Diner. But while fairytale endings are fun, the rosy conclusion of Waitress seems to work against a story about the realities of a working gal’s life. Still, it’s lovely to leave the theatre and go hunting for a good piece of The-Show-is-Over pie. Served, probably, by a waitress with Broadway stardom on her mind.

Published on May 31, 2016 12:00

Beverly in Movieland

I write twice weekly, covering topics relating to movies, moviemaking, and growing up Hollywood-adjacent. I believe that movies can change lives, and I'm always happy to hear from readers who'd like t

I write twice weekly, covering topics relating to movies, moviemaking, and growing up Hollywood-adjacent. I believe that movies can change lives, and I'm always happy to hear from readers who'd like to discuss that point.

...more

- Beverly Gray's profile

- 10 followers