Beverly Gray's Blog: Beverly in Movieland, page 99

May 27, 2016

Harold Lloyd’s “The Freshman” Speeds into Sleepy El Segundo

The Old Town Musical Hall in El Segundo, California is a precious glimpse into the Hollywood of the past. Located just off Main Street in a sleepy bedroom community surrounded by aerospace plants, the Musical Hall started off back in 1921 as the State Theater, dedicated to the screening of silent movies. It gradually lapsed into disuse until 1968 when two musicians, Bill Field and Bill Coffman, purchased a 1925 Mighty Wurlitzer Theater Pipe Organ from the Fox West Coast Theatre in nearby Long Beach.

The two Bills installed the organ (which boasts four keyboards, 260 switches, and all manner of controls and pedals) in their El Segundo theater, and the Musical Hall was born. Today, the little theater is a landmark of Old Hollywood kitsch. The various organ pipes, not to mention cymbals, drums, and other music-making apparatus, have been lovingly refurbished in glow-in-the-dark colors. The organ itself is surrounded by all manner of statuary, including a Buddha on one pedestal, a plush Mickey Mouse doll on another. The stamped metal ceiling is newly installed, and it gleams.

The Music Hall’s movie screenings (normally only on weekends) feature a brief Wurlitzer concert, complete with sing-along, followed by a short subject. I saw Laurel and Hardy’s knockabout farce, “The Chimp,” and then a feature-length gem, Harold Lloyd in The Freshman, from 1925. The Music Hall shows plenty of classic talkies, including old musicals and horror flicks. But it’s at its best when it can show off the Mighty Wurlitzer as an accompaniment to a legendary silent classic.

Harold Lloyd, of course, was one of the three great comedians of the silent era, the others being Charlie Chaplin and Buster Keaton. Lloyd’s trademark was his large horn-rim glasses. He looks something like a WASP Woody Allen, but one whose slight built masks a surprising athleticism. In The Freshman, probably his most successful film, he plays an eager young collegian (“Call Me Speedy”) who’s determined to win friends and influence people as he matriculates at Tate University. He quickly depletes his college savings buying ice cream for everyone on campus, and amuses the student body by launching into a silly little dance step whenever he’s introduced to someone new, under the mistaken impression that this is his path to social success. He’s fundamentally an innocent surrounded by sophisticates and snobs. In one of the film’s most hilarious sequences, he hosts an elaborate “Fall Frolic” while wearing evening clothes that keep splitting at the seams because his ensemble is only loosely basted together. (His tailor, trying to make amends, is creeping around in the background, re-attaching sleeves while he’s trying to act suave.) When he tries out for the football team, he succeeds only in serving as a tackling dummy and water boy. Nonetheless, he somehow manages to win the big game—and to learn some life lessons about the value of being oneself.

The Freshman is priceless partly because of its glimpses of early Los Angeles, from the days before the big studio lots sprang into being. The big football game, for instance, is played at the Rose Bowl. (Cari Beauchamp’s invaluable My First Time in Hollywood: Stories from the Pioneers, Dreamers and Misfits Who Made the Movies has a lot to say about those early years.) It’s important too for its picture of how college life was regarded at a time when most Americans hardly dared aspire to step onto an ivy-covered campus. But most of all it lives on because it’s screamingly funny. A big thank-you to the Old Town Musical for bringing it to us in all its glory.

Published on May 27, 2016 06:00

May 24, 2016

Nichols vs. Altman: Two Paths to Glory

For months I’ve been researching director Mike Nichols and the second film of his career, 1967’s The Graduate. Last night, on my version of a busman’s holiday, I watched Robert Altman’s 1975 film, Nashville. Both Nashville and The Graduate ably reflect a fertile period of American filmmaking that has come to be called the New Hollywood. Still, they are shot in highly disparate styles. A “making-of” documentary that accompanies the Criterion DVD of Nashville has convinced me that one key difference between the two movies lies in the personalities of two very different directors.

Mike Nichols began as a comic actor, hailed for his satirical performances with Elaine May. After May broke up the act, Nichols moved on to even greater success as a director of Broadway comedies. Neil Simon’s Barefoot in the Park catapulted him into a career in Hollywood as well as on the Great White Way. Elizabeth Taylor chose him to direct her and spouse Richard Burton in a film adaptation of a controversial stage play, Edward Albee’s Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? Nichols’ version was a popular and critical success. But – given that it focused on a mere four actors who played out their corrosive interaction against a single interior set – it did not take full advantage of the motion picture medium.

On The Graduate, Nichols was far freer to experiment technologically. The film is full of flashy camerawork that explores the psychology of the characters while conveying what Nichols saw as the sterility of SoCal life. Working with a cast made up largely of stage veterans, he rehearsed for three weeks before the start of shooting. In rehearsal, actors were encouraged to contribute their own ideas, but once the cast moved into production there was little tolerance for deviation from the finalized script. In his early films, Nichols was brutally hard on his performers. Dustin Hoffman, for one, felt completely off-balance, convinced he wasn’t up to Nichols’ standards of excellence. On Nichols’ part this was at least partially strategic: it was both a way of amping up his leading character’s agitated mental state and a trick to deflect attention from his own jangled nerves.

Robert Altman, by contrast, came across as jovial and laidback. In casting Nashville, he relied solely on instinct, giving major roles to those (like singer Ronee Blakley) with no real acting experience, once he sensed they were right for a particular part. (Explains Keith Carradine, “He hired behavior; he hired essence.”) On set, a performer was free to discard the script pages and try something completely different. Altman’s experiments with zoom lenses and with multi-track audio recording allowed him to shoot crowd scenes in which no one quite knew which characters would ultimately be featured on camera at any given moment. And the film’s many songs were all recorded live. The result: an improvisational feel that contributes to Nashville’s life-like spontaneity.

Though Altman hardly lacked a strong sense of self, he wanted his cast to blend into a community. That’s why he kicked off location filming with a 4th of July barbecue at the lovely rustic cabin he and his wife had rented. The barbecues continued throughout the months of shooting, and actors were encouraged to watch dailies together, thus reinforcing their feel for the overlapping stories in which they all played a part.

Almost everyone was housed at a local motel throughout the shoot. The one exception was Karen Black, who was whisked via limo to Nashville’s best hotel. Castmates who complained discovered Altman’s logic: no one else in the film was supposed to like Black’s character very much.

Published on May 24, 2016 06:00

May 20, 2016

Fasten Your Seatbelts: There’s a Letter in the Mail for Three Wives

It’s hard to believe now that, back in 1949, Joseph L. Mankiewicz’s A Letter to Three Wives was a really big deal. But at the 1950 Oscar ceremony, Mankiewicz won two Oscars, for both writing and directing this film. It was up for Best Picture too, but lost to a movie I consider far more memorable, a still-timely story of political corruption called All the King’s Men. (The following year, Mankiewicz made Oscar history by again winning screenplay and director honors. That 1950 release, which won a total of six Oscars, is a bonafide Hollywood classic, All About Eve.)

A Letter to Three Wives can fairly be called a woman’s picture, because its topic is wedlock, as seen through the eyes of three married women who are pals living in a small suburb. The structural gimmick is that the three, while en route to a good-hearted outing with some underprivileged kids, receive a note from a so-called friend telling them she has just skipped town with one of their husbands. This shocking news leads to extended flashbacks, in which we see the fault lines of each woman’s marriage.

There’s Jeanne Crain as a fresh-faced farmer’s daughter who met her handsome and wealthy husband while serving as a WAVE in World War II. She still feels like a rube and an outsider. There’s Ann Sothern, the career gal who out-earns her schoolteacher spouse (a young Kirk Douglas!) but kowtows to the producers of the sappy radio program for which she writes. There’s sultry Linda Darnell, who’s succeeded in persuading a retail tycoon (Paul Douglas) to marry her. The marriage was her ticket out of poverty, but it hasn’t entirely brought happiness. And always lurking in the vicinity, though never really seen on camera, is Addie Ross, whom each of the three husbands views as their town’s prime exemplar of class and sex appeal. For each of them, she seems to be the One Who Got Away, and we anticipate finding out at the end of the film exactly who—and what—she’s gotten away with stealing. The film’s cleverest touch is Addie’s voice-over narration. It’s provided (without screen credit) by Celeste Holm, whose self-satisfied purr tells us all we need to know about Addie Ross’s attitude toward domestic life.

A Letter to Three Wives began, fittingly, as a novel published in 1946 within the pages of Cosmopolitan magazine. The original, I’m told, was A Letter to Five Wives. The filmmakers started out planning to tell four marital stories, then removed one that was supposed to feature Anne Baxter. (She certainly got her revenge in All About Eve!) I gather the movie also differs from the novel because of its unambiguously happy ending. Not surprisingly, for that era, career gal Ann Sothern patches up her marriage by standing up to her demanding boss for the very first time. (I was glad to see that she doesn’t go so far as to quit her writing career altogether – she merely makes it clear that from here on out her weekends belong to her spouse and kids.) The reconciliation of Linda Darnell and Paul Douglas is frankly unconvincing, given their constant bickering earlier in the film, but I guess audiences in 1949 were in desperate need of reassurance that marriages could really work.

The DVD on which I viewed this film contains a fascinating character sketch of actress Linda Darnell, billed as “Hollywood’s Lost Angel.” What a turbulent life she led! Too much success too soon, bad marriages, and a death much too early. No wonder she was so convincing as the film’s beautiful cynic.

Published on May 20, 2016 19:30

May 17, 2016

Stuntwomen: Soaring Without Wings or Wigs

How do you feel about a man wearing a dress and a woman’s wig? No, I’m not here to discuss the transgender-bathroom question that’s currently roiling North Carolina. My topic today is stuntwomen. As Mollie Gregory points out in her illuminating Stuntwomen: The Untold Hollywood Story , throughout the history of motion pictures men have been ready and eager to step in, don the wig, and take on stunt assignments that should much more logically go to women. Gregory, a moviemaker and a delightful speaker, is known for her books about the female presence in Hollywood. (Her Women Who Run the Show chronicles the rise of women in the film industry’s executive ranks.) Now she has interviewed sixty-five stuntwomen and looked back to the earliest days of moviedom in order to bring us the first-ever history of the women who – often in skirts and high heels – risk their lives to bring us movie thrills and spills.

I was lucky enough to hear Mollie, along with a panel of current stuntwomen, speak at a recent luncheon event co-sponsored by Women in Film. Mollie marveled at “how tough and gallant women are.” Her subjects love what they do, and speak of the joy of “making a moment come alive visually by using your body and soul.” Still, they have suffered greatly from job discrimination and from sexual harassment. In order to work, they’ve had to battle paternalistic men who feel they’re protecting women, as well as mercenary males who want to fatten their own paychecks by denying stuntwomen the chance to ply their craft.

In the early days, silent movie performers did their own stunts, with little in the way of safety precautions to protect them. Some of those early actresses loved doing high dives and driving fast cars, firing guns and leaping from bridges. But once Hollywood had evolved into a hierarchical industry in the 1920s, men took over. For decades women were squeezed out as stunt performers, and certainly had little opportunity to move into the more executive position of stunt coordinator, the person responsible for designing stunts and ensuring the safety of those who perform them. One of the luncheon’s special guests was the son of William Wellman, who pointed out with pride that his father, on a 1951 film called Westward the Women, had been the first Hollywood director to hire a female stunt coordinator, Polly Burson. It made sense, on a movie with a heavily female cast, to put a woman in charge of stunt actors—but Wellman still had to fend off flak from studio brass for his decision.

Several of the women on Gregory’s panel have themselves made history as stunt coordinators. They spoke of dangers they’ve survived, of injuries they’ve overcome, and of how stuntwomen face special challenges because they’re expected to perform tricky maneuvers not in padded clothing but rather in skimpy tank tops and teeny skirts. Annie Ellis, a third-generation stunt performer, noted that it’s constantly necessary to remind filmmakers not to risk lives by “rushing the shot.” She remembers, on the movie Twister, the filming of a tricky stunt that involved a tanker truck plummeting to earth, followed by a huge explosion. The scene had been filmed successfully, but needed to be re-shot several weeks later because of camera problems. Because this was a re-do, the director didn’t see the need for a rehearsal. It’s in situations like these that stunt coordinators need to stick up for their team’s well-being.

What can you say to a director who asks you to do the impossible? “No—unless you want to show us first.”

Published on May 17, 2016 12:51

May 13, 2016

Riding Out a Twister: “What Stands in a Storm”

Last week, tornados were touching down in Oklahoma, spreading death and destruction in their wake. Personally, I know tornados only from movies, like 1996’s Twister. But those who’ve actually survived them tend to laugh at Hollywood’s portrayal of storm chasers, the hardy (and sometimes faintly crazy) souls who risk their lives while trying to study extreme weather events.

Kim Cross knows about tornados first-hand. A resident of Birmingham, Alabama, she’ll never forget April 27, 2011.

That was the climax of a three-day outbreak, when 349 tornadoes raked 21 states in the American South. One of them, a so-called EF4 multiple-vortex tornado, flattened huge swaths of Birmingham and Tuscaloosa, seat of the University of Alabama. Like everyone else on that fateful day, Kim stayed glued to the TV broadcasts of meteorologist James Spann, who forecast the path of the oncoming twister. As it seemed to head straight for her neighborhood, she grabbed a helmet and hunkered down with her family in her home’s safest room. Fortunately for Kim, the tornado struck seven miles away, leveling almost everything in its path. Others weren’t so lucky. That tornado claimed hundreds of lives, not to mention property damage. Many of Tuscaloosa’s stately oaks, hundreds of years old, were toppled by the force of the winds. The city will never look the same again.

As a journalist at Southern Living, Kim was asked to cover the superstorm’s aftermath. That’s how she came to unearth dozens of heartwarming stories of survivors helping one another get past the tragic day. After receiving multiple awards for her magazine work, she was primed to write a book. What Stands in a Storm: Three Days in the Worst Superstorm to Hit the South’s Tornado Alley was published in 2015. It’s a powerful narrative, which follows the storm’s path by way of the experience of both survivors and victims. In one chapter, “Slouching Toward Tuscaloosa,” Kim vividly cuts between the stoic men at a fire station, storm chasers photographing a funnel that’s heading straight toward them, a vigilant hospital administrator, and three college seniors exchanging frantic text messages with their loved ones back home. Binding these vignettes together is the TV voice of James Spann, warning one and all to get out of harm’s way.

As a trained journalist, Kim was hugely concerned with accuracy. That’s why she established for herself some ground rules based on the way cinematographers capture the visual landscape: “I couldn't let you, the reader, see or know anything the character in that scene didn't see or know at that moment . . . . To help me do that, I imagined myself as a camera operator. In the first scene, we are panned out, seeing the big picture. In the second scene we zoom in a bit and can see the inside of a firehouse. In the third scene we zoom in even more, on two college students in a car.” Suspense comes from the fact that the reader never knows ahead of time who will live and who will die. Kim understands these people so well that she can convey their essence through their actions and social media exchanges, without ever putting into their mouths dialogue she can’t verify.

And she’s terrific at using words to set the scene: “At the Salvation Army, thirty-five people sought refuge in the dining hall as the wind blasted open the doors and stripped away the roof. A steel building that crumpled like a wad of foil was hurled into the seventy-bed shelter, which collapsed upon the impact. An electrical substation twisted like a telephone cord, and the lights went dark across town.”

Kim Cross, the 2016 recipient of ASJA honors for full-length non-fiction, will be a featured speaker on my “Award-Winners: From Pitch to Publish” panel at the annual conference of the American Society of Journalists and Authors in New York City. It all takes place May 21, and the public is cordially invited.

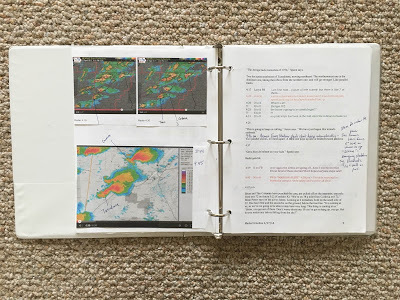

By the way, the paperback edition of Kim’s book has a new subtitle: A True Story of Love and Resilience in the Worst Superstorm in History. And here’s a sample of the elaborate timeline she created to help tie the storm’s moment-by-moment progress to her narrative.

On the left are weather maps charting the advance of the tornado

On the left are weather maps charting the advance of the tornado

Published on May 13, 2016 10:38

May 10, 2016

Woody Allen: Schlemiel and Stud, Coward and Hero

Woody Allen is having a moment—again. His whimsical face (he wears his 80 years lightly) is gracing the cover of this week’s Hollywood Reporter, because his latest film, Café Society, is opening the 2016 Cannes Film Festival on May 11. He’s a deeply shy man, one who is hardly a publicity hound. But with a career that spans six decades, and encompasses both prestigious awards and personal scandal, he has had to accept the fact that he’s a public figure, like it or not. He’s also surprisingly gracious to writers who want to understand what makes him tick.

One such is a friend and colleague of mine, biographer David Evanier. David, who has previously written about Bobby Darin, Tony Bennett, and wiseguy balladeer Jimmy Rosselli, makes no secret of the fact that he’s a Woody Allen fan from way back. Hoping to deliver the first serious chronicle of Allen’s life since Eric Lax’s 1991 biography, he wrote Woody , which was published by St. Martin’s Press last fall. David, a serious researcher, has done a masterful job of locating people of importance in Allen’s world, including boyhood chums and the shy first wife he married when he was 20 and she 17. (They used to entertain one another by playing recorder duets.) He also managed to initiate an ongoing email conversation with the man himself, and finally was able to meet him in person.

A writer for Time magazine once hailed Allen’s screen image as that of as “a champion nebbish, one that every underdog in America could—and soon would—identify with. Allen had invented a perfect formula for an anxious new age: therapy made hilarious.” David Evanier, though, emphasizes that the Woody seen on screen is not identical to the writer-director who early on perfected this persona. The real Woody Allen is altogether smarter, shrewder, and trickier than the character he’s known for playing. That’s not to say that his life has been altogether admirable. He has the long-ingrained habit, for one thing, of walking away from people and institutions when he tires of them. This happened with his stand-up career and also with his first wife, Harlene. (In fact, like his character Alvy Singer in Annie Hall, he seems to resist being a part of any club that would have him for a member.) Then, of course there was the awkwardness of his breakup with longtime partner Mia Farrow when she discovered his stack of nude photos of her adoptive daughter Soon Yi Previn. This episode is hardly Woody Allen at his best. But, David provides plenty of evidence refuting Farrow’s claim that her former lover had molested her seven-year-old adopted daughter, Dylan. Farrow comes off, in fact, as a pathologically troubled woman.

David seems happiest, though, when exploring Allen’s artistic accomplishments. Sadly, despite his enormous talent for making people laugh, Woody tends to disparage comedy as an art form, yearning instead to be known for serious drama. Nor is he easy on himself in general, saying, “The only thing standing between me and greatness is me.” He respects only six of his forty-plus films: The Purple Rose of Cairo, Match Point, Bullets Over Broadway, Zelig, Husbands and Wives, and Vicky Cristina Barcelona. David Evanier is far more enthusiastic than Woody himself abut what Woody has wrought. As he writes, “All the time we thought [Woody Allen] was a neurotic mess, he was playing the ultimate magic trick on us. Broken, needy, an impractical dreamer, a shlepper on screen, in life he was the artist who kept going, was never destroyed, who got it all.”

Published on May 10, 2016 14:06

May 6, 2016

Meta Carpenter Wilde and the Script Supervisor’s Unblinking Eye

Is there any movieland job more thankless than that of the script supervisor? But directors can’t do without her. Yes, it’s generally a her – for generations she was known in movie credits as the “script girl.” And in the parlance of movie folk, her duties were that of the perfect secretary or the perfect wife: to stand at the (usually male) director’s side and keep him from running off the rails.

I thought about this while listening to a tribute to Tracey Scott, who just died of cancer at the sadly young age of 46. In the course of her career, Scott moved from television into movies, working closely with some of the industry’s most promising directors. Starting in 2013, she plied her craft on Her (for Spike Jones), American Hustle (for David O. Russell, with whom she also worked on Joy), Whiplash (for Damien Chazelle), Foxcatcher (for Bennett Miller), and Black Mass (for Scott Cooper).

But what does a script supervisor do, exactly? It’s not what you’d call a creative job, but rather one that requires precision, a great eye, a talent for record-keeping, and a willingness to go without personal glory. I tried it myself once, while shooting – with a team from Women in Film -- a 60-second PSA for a charity called My Friend’s Place. Standing at the director’s elbow, I was required to document, by way of carefully codified notes, every single take, noting the camera position in each. My notes would eventually be turned over to the film editor, who used them to assemble a rough-cut that made logical and dramatic sense.

My task on the PSA was relatively simple, compared to that of the script supervisor who oversees a 90-minute feature film shot (probably in many different locations) over a period of weeks and months. Experienced script supervisors, like Tracey Scott, keep tabs on every detail of the film-in-progress. They are always on the watch for continuity errors (like a necklace that changes positions in relationship to the collarbone from shot to shot, or a Band-Aid that sometimes appears on the wrong arm). And they know precisely what time of day it needs to be at various points in the story, so that the gaffer can appropriately light the set. Above all, as David O. Russell made clear in an interview following Scott’s death, they serve to keep the director focused on the minutiae of the task at hand.

Script supervisors are usually unsung heroes. One, though, had her own small bit of celebrity. Meta Carpenter, who was then secretary and script girl to the director Howard Hawks, had a serious fling with the novelist William Faulkner, who in the 1940s was trying to earn money as a Hollywood screenwriter. Carpenter’s 1976 memoir, A Loving Gentleman , details their trysts at what was then a romantic out-of-town destination, a cozy bungalow at Santa Monica’s seaside Miramar Hotel. Carpenter’s first script supervisor jobs (on films like Hawks’ To Have and Have Not) were uncredited. Later, as first Meta Rebner and then Meta Wilde, she worked on such award-winning productions as To Kill a Mockingbird (1962) and In the Heat of the Night (1967). She also was a fixture on Mike Nichols’ first films. On the set of The Graduate, Dustin Hoffman recalls her as a stickler for accuracy, who never allowed him to deviate one iota from what was written in the script. He still remembers her objecting, in her soft but firm Tennessee drawl, to the way he read one particular line, saying, “That wasn’t a period, that was three dots.”

Published on May 06, 2016 11:17

May 3, 2016

Presidential Politics 2016: Choosing the Real American Idol

Ted and Carly?

Ted and Carly? Those who tuned in to see Senator Ted Cruz announce Carly Fiorina as his running mate (on the off chance he’s named the 2016 presidential candidate of the Republican Party) were in for a surprise when she started singing. Who knew that the former CEO of tech giant Hewlett-Packard had musical aspirations? But it started me thinking. We’re all totally sick of this never-ending presidential primary season. Who wants to read more about Cruz speeches, Bernie rallies, Trump tweets? Caucuses schmaucuses – how about something completely different? Something fun and telegenic. Like, perhaps, a TV reality show.

The biggest challenge would be which format to pick. There’s the aptly-named Big Brother: dump all the candidates in an isolated house (Camp David, maybe?) and watch the dogfight. Along the same lines, there’s Survivor: wouldn’t it be lovely to send everyone to some distant island, full of scorpions and other nasty critters, and discover just who is capable of emerging triumphant? And let’s not forget the very weird Naked and Afraid. I suspect that Hillary Clinton would not look presidential if she had to shed her pantsuit and go on a wilderness adventure in the altogether, but it would be instructive to learn which of her male opponents has the balls (sorry!) to compete minus jockey shorts and hair gel. (Of course, if candidates’ spouses were included on this trek, Melania Trump would have a clear advantage, since she seems to be quite comfortable wearing little or nothing. I can’t imagine Heidi Cruz enjoying this, though Bill Clinton would certainly be up for getting into the spirit of things.)

But let’s dial it back a bit, and consider formats that require less nudity and more talent. Carly Fiorina has already made it clear that she enjoys singing. So what about reviving the now defunct American Idol for the duration of the presidential campaign? Tammy Wynette’s “Stand by Your Man” would be a natural for Hillary. For the Donald, I suggest reviving a ballad from Frank Loesser’s 1961 hit Broadway musical, How to Succeed in Business Without Really Trying. (You may not recall – I certainly didn’t – that the show is based on a humorous parody of a how-to manual, whose subtitle is “The Dastard's Guide to Fame and Fortune.”) Anyway, the song I have in mind is called “I Believe in You.” Here are the opening lyrics:

“You have the cool, clear eyes

Of a seeker of wisdom and truth;

Yet there's that upturned chin

And that grin of impetuous youth.

Oh, I believe in you.

I believe in you.”

Yes, the leading man sings the song—to himself, as he’s looking into his shaving mirror. As for the other candidates, I can think of more than one (John Kasich? Chris Christie?) who’d be well suited to warbling “(I Can’t Get No) Satisfaction.”

Or maybe—on behalf of candidates who are certainly tone-deaf from time to time—it’s better if our show is a variation on Dancing With the Stars. I can imagine Jeb Bush scoring with a sedate little waltz. Ted Cruz probably does a mean Texas two-step, and Marco Rubio (who has a Cuban heritage and high-heeled cowboy boots) is surely a whiz when it comes to salsa dancing. Given his kibbutz years, Bernie Sanders might be able to manage a spirited hora. And I’d certainly like to see Dr. Ben Carson do the cupid shuffle.

There’s a brides-choosing-wedding-gowns show I love, called Say Yes to the Dress. How about, this primary season, something like Say No to the Blow-Hard? Or, perhaps, simply Say No to the Schmo? Works for me!

Published on May 03, 2016 12:30

April 29, 2016

Back in the USSR: Gary Shteyngart, “Hipsters,” and the Allure of American Movies

Like so many of today’s rising American novelists, Gary Shteyngart was born in another country. He’s a product of a place that no longer exactly exists: Leningrad has, since the collapse of the USSR, reverted to its older and more gracious name, St. Petersburg. When Shteyngart (originally called Igor) came into the world on July 5, 1972, his parents were typical products of the Soviet Union. But they were also Jewish, which meant they knew all about official anti-Semitism. So when little Igor was seven they packed their belongings and made their way to New York City, where a whole new world awaited them.

In a vivid 2014 memoir, Shteyngart details the making of an American. Transforming himself from Igor into Gary wasn’t easy. He was a particularly fearful child, partly because of his roots and his years of displacement. It didn’t help that his father expressed his love for his only son by harping on his weaknesses. Hence his around-the-house nickname, “Snotty,” and the phrase that becomes the memoir’s title, Little Failure. At times in the face of his painful growing-up, Gary Shteyngart seems all too worthy of this kind of curt dismissal. Yet he has a talent for language, and the kind of cross-cultural curiosity that brings his words to life. That’s why he’s the author of three acclaimed novels, and in 2010 was named one of The New Yorker’s “20 under 40” literary lights.

So what does Shteyngart’s own story have to do with movies? When he moved to the U.S., he knew little of American movies and television. But as a pre-teen, on fishing trips with his father, he discovered the joy of small-town cinemas, watching movies like 1985’s Cocoon. Here’s how he describes his new passion: “At this point in my life, Hollywood can sell me anything—from Daryl Hannah as a mermaid to Shelley Duvall as Olive Oyl and Al Pacino as a rather violent Cuban émigré. Watching movies in the air-conditioned chill I find myself wholly immersed and in love with everything that passes the camera lens. . . At the movie theater my father and I are essentially two immigrant men—one smaller than the other and yet to be swaddled by a thick carpet of body hair—sitting before the canned spectacle of our new homeland, silent, attentive, enthralled.”

This passage from Shteyngart points to the impact of Hollywood movies on recent arrivals to the U.S. But an unlikely Russian musical, made in 2008, chronicles the impact of Hollywood on those who once lived under the Soviet system, “where sneezing too loud is enough to get you arrested.” In the world of the film Hipsters , it’s 1955, and restless Soviet youth are besotted by boogie-woogie, pompadour hairstyles, and zoot suits in electric shades of green, raspberry, and mustard. Opposing them are the drably-clothed Young Communists, armed with scissors to cut off too-wide neckties. A hip young man can be sent to jail for buying Charlie Parker albums, because “a saxophone is only one step away from a switchblade.”

Hipsters is full of outrageous color and wild musical numbers. But one of the film’s most poignant moments comes when a character who has dubbed himself “Fred” gets (through his father’s connections) the opportunity to actually study in America. To do so, with the hypothetical goal of joining the Soviet diplomatic corps, he must get married, and have his hair shorn into an ideologically acceptable crewcut. When he returns, he’s sadder but wiser. As he tells his friends, the “cool” American-style clothing prized by the Russian hipsters just doesn’t exist in the USA.

Published on April 29, 2016 12:44

April 26, 2016

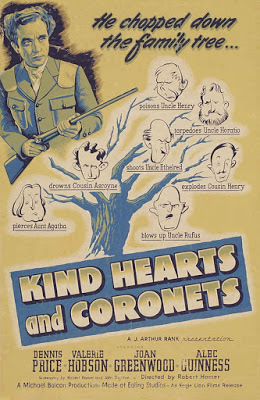

“Kind Hearts and Coronets” -- Mayhem and Mirth on a Tight Little Island

My trip to see a delightful touring production of a Broadway musical hit, A Gentleman’s Guide to Love and Murder, had the side benefit of sending me back to the movie made from the same source material. It’s Kind Hearts and Coronets, the very dark 1949 British comedy from the fabled Ealing Studios. The plot in both play and movie (which are loosely based on a novel from 1907 called Israel Rank: The Autobiography of a Criminal by Roy Horniman) involves a young man born to the daughter of a noble British family. She was cast out by her relatives when she made what they considered an unsuitable marriage; now her son is determined to regain his lost inheritance by murdering all those who stand between him and the dukedom he feels he deserves. The joke in both film and play is that the eight victims (including a scalawag, a tipsy churchman, and a suffragette) are all played by the same actor.

On film it’s the protean Alec Guinness, whom younger generations associate with the mystical Obi-Wan Kenobi in the original Star Wars. Guinness also won an Oscar for his martinet colonel in The Bridge on the River Kwai, as well as nominations for several widely different roles. In the heyday of Ealing Studios, he revealed his talent for transforming himself by way of accent, posture, and makeup in such wild comic Ealing gems as The Lavender Hill Mob, The Man in the White Suit, and The Ladykillers.

One subtle difference between the Broadway musical and the black-&-white British film (both of which are set back in the Edwardian era, 1901-1910) lies in the tone of each. Given the subject matter, both are necessarily bleak, with heroes who are unapologetic murderers, and furthermore have no qualms about romancing married women. But the stage musical relies more on whimsy: somehow its leading man can more easily be forgiven when he accidentally finds himself on the path to murder. On film, however, the same character is plotting from the start his plan to lop off branches of his family tree. And though his victims are not wholly sterling characters – rather, they’re weak-minded individuals who never would be missed, as Gilbert and Sullivan would have it -- they certainly don’t deserve the grizzly fates that befall them. And in the film there’s lots of collateral damage that our more skittish age might find unnerving.

The amorality of the film version is somewhat surprising when you learn about the head of Ealing Studios, the eminent Michael Balcon. A documentary included with my DVD traces the entire history of the studio. Balcon, who brought together and firmly oversaw a talented stock company of directors, designers, and actors, was himself known to all as a rather prudish man, much given to promoting English virtues on screen. Still, the studio, which under his direction spanned the World War II era through the 1950s, is today revered not for its serious war dramas and tame little fables but rather for the creepy Dead of Night as well as for the tonally complex comedies that Guinness made for such directors as Alexander McKendrick (The Ladykillers) and Charles Crichton (The Lavender Hill Mob).

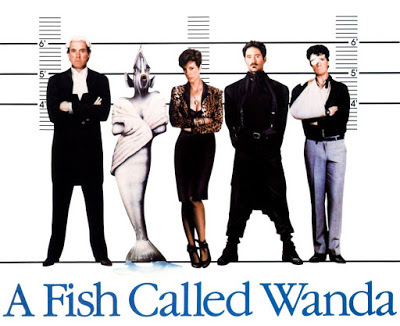

Crichton, who began as a film editor, was about 41 when he shot The Lavender Hill Mob, about a clever heist conducted by some unlikely mild-mannered Brits. Almost four decades later, he worked closely with John Cleese to bring to the screen A Fish Called Wanda (1988), another heist film—and one of the funniest movies ever made.

Published on April 26, 2016 09:30

Beverly in Movieland

I write twice weekly, covering topics relating to movies, moviemaking, and growing up Hollywood-adjacent. I believe that movies can change lives, and I'm always happy to hear from readers who'd like t

I write twice weekly, covering topics relating to movies, moviemaking, and growing up Hollywood-adjacent. I believe that movies can change lives, and I'm always happy to hear from readers who'd like to discuss that point.

...more

- Beverly Gray's profile

- 10 followers