Beverly Gray's Blog: Beverly in Movieland, page 96

September 9, 2016

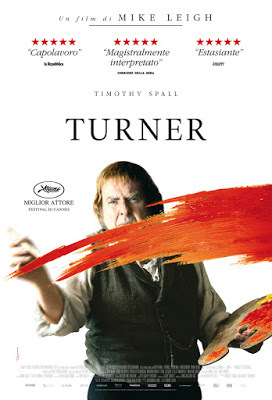

“They Call Me MISTER Turner”

There are times, especially in late summer, when I feel the need for a movie orgy. In my case, this means a trip to the Santa Monica Public Library, where I scan the shelves holding DVDs, in search of a good assortment of films I haven’t yet seen. Last week, I randomly chose the letter M, and found myself going home with everything from David Cronenberg’s Maps to the Stars to Mad Max: Fury Road. And also two “mister” movies: 2014’s Mr. Turner and an oldie, Mr. Blandings Builds His Dream House.

Mr. Blandings is a classic black-&-white studio flick, featuring the comedic talents of Cary Grant, Myrna Loy, and Melvyn Douglas. Filmed in 1948, based on a popular novel of the day, it epitomizes the upbeat domesticity of the post-World War II period. The film starts with a witty paean to life in New York City: while narrator Douglas describes the Big Apple’s superb transportation system, charming cafes, and bracing weather, we watch city-dwellers squeeze themselves into overcrowded subway cars, gobble down lunch at a gritty hash-house, and try not to slip on snowbound street corners. Cut to the cramped apartment in which Grant, Loy, and their two daughters dodge each other in a cramped bathroom and try to extricate their belongings from overstuffed closets.

As an up-and-coming ad executive, Grant feels entitled to live someplace better. He and Loy, both incurable optimists, spring for a decrepit Revolutionary War-era estate in rural Connecticut. When it proves unsalvageable, they decide to build a dream house, one with lots of closets and bathrooms and nooks and hideaways. Anyone who’s ever tried remodeling will know what comes next. As a team of blunt-spoken Yankee craftsmen sets to work, hilarity really does ensue. Let me end by mentioning the film’s single black character, Gussie the live-in housekeeper. She’s played by Louise Beavers, whose long filmography includes the original 1934 Imitation of Life. Her role is small, but it is she who holds the key to the essential advertising slogan that will save Mr. Blandings’ career. And give this film its inevitable happy ending.

Mr. Turner is a horse of a different color. This biopic of England’s greatest landscape painter, J.M.W. Turner, is suitably beautiful to look at. Its gorgeous seascapes and sunsets are a fitting homage to an artist revered for his handling of light. And British filmmaker Mike Leigh, who had earlier made the charming Topsy-Turvy about the complex musical partnership of Gilbert and Sullivan, pays appropriate homage to a genius who was also a very flawed man. The film Mr. Turner surveys the years leading up to Turner’s death in 1851. The problem with many biopics (especially those of the cradle-to-grave variety) is that they feel obliged to include every event in a great man or woman’s life, so that we’re left with a long string of fairly unrelated episodes. Though Mr. Turner covers 25 years in a fairly leisurely fashion, it holds together as an exploration of Turner’s fascinatingly self-contradictory character. He can be gruff and crude (even in a sexual sense) to those around him, but then reveals an unexpected depth of feeling when encountering a fine vista or a beautiful piece of music. He can be unspeakably cruel to a former lover and her children, but also charmingly gracious to the widow whose heart he wins late in life. As played by Timothy Spall, whose performance was honored at the Cannes Film Festival, Mr. Turner is rotund and ungainly, with tics and harrumphs that are not easy to love. Still, the film adores him, and I did too.

Publicity still for "Mr. Blandings Builds His Dream House." As part of the film's promotion, new homes were erected in locales all over the country.

Publicity still for "Mr. Blandings Builds His Dream House." As part of the film's promotion, new homes were erected in locales all over the country.

Published on September 09, 2016 11:43

September 6, 2016

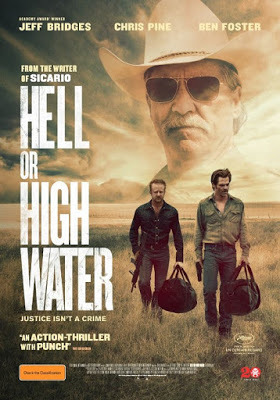

Hell or High Water: Bleak is Beautiful

One of my screenwriting students in UCLA Extension’s Writers’ Program wanted to know if I’d seen Hell or High Water. She wrote, “To me, it was the quintessential demonstration of how to write implicit dialogue: subtext delivers exposition. Scene after scene. Wow.” Naturally, with that kind of endorsement from a student of the craft, I had to check it out for myself. And yes – wow!

Hell or High Water is a tough little indie, set mostly in Texas, about some roughnecks who set out to rob banks, but whose motives are more complicated than they might first appear. This is not exactly brand-new territory (in terms of either the plot or the landscape). Bonnie and Clyde, for one, traveled through much of the same physical and psychological terrain. But unlike Bonnie and Clyde, which featured a pair of real-life Depression era outlaws, Hell or High Water reflects life as we know it today. Though midland Texas, as shown in this film, is still cowboy country, the social anxieties we see on screen could easily be ripped from tomorrow’s headlines.

It’s a beautiful film to look at and to listen to. I’m not exactly a fan of western music, but the score of Hell or High Water is augmented by haunting tunes that enhance the wide open spaces we see on screen. And those parched landscapes, dotted with dying little towns, pumping oil wells, and double-wide trailers, have their own eerie beauty. The cinematography is the work of the very talented Giles Nuttgens. His name wasn’t familiar to me, but I was pleased to discover he was responsible for another marvelous indie with water in its title: Deepa Mehta’s gorgeous glimpse of widowhood in the holy Indian city of Varanasi. Mehta’s Water revels in its liquid beauty. In Hell or High Water, there’s in fact a lot less water than oil. Or beer. But this is a visually stunning movie, all the same.

Now . . . about the screenwriting elements that so impressed my student. The script is the work of Taylor Sheridan, who also wrote the much-admired Sicario, another film with a Southwestern setting. It’s probably because Sheridan is a working actor that he so keenly grasps how to delineate character with the tiniest scraps of dialogue. By the end of the film, we truly know these people through their behavioral quirks and bad jokes. When we first meet the film’s two bankrobbing brothers (played to a fare-thee-well by Ben Foster and the mesmerizing Chris Pine), their faces are covered by ski masks and we’re not really sure which is which. It’s not long, however, before we come to respect the gaping differences between them, differences that will help shape the plot. Then there’s their opposite number, the retirement-age Texas Ranger played by the always convincing Jeff Bridges. Though L.A.-born, Bridges has long been identified with the Southwest, from his breakthrough appearance in The Last Picture Show (1971) to his Oscar-winning turn in Crazy Heart (2009). He has a genius for playing lived-in characters, and this is one of his very best.

One aspect of Sheridan’s writing (aided by the direction of David Mackenzie) that struck me as paticularly savvy is its tendency to withhold information from the audience as long as possible. As the film moves forward, we get only small hints about the rationale behind these particular robberies. The payoff, when it comes, is that much more provocative because we’ve put most of the pieces together ourselves. It helps us appreciate what a man will do when he’s stuck between hell and high water.

Published on September 06, 2016 13:56

September 2, 2016

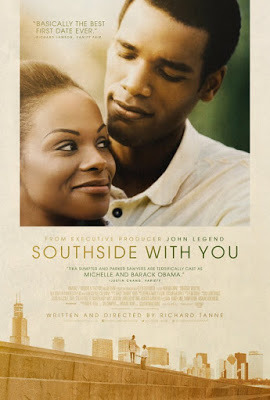

Southside with You: A Future President Finds Love

Southside with Youis a low-key little movie about a first date that doesn’t exactly start out as a date. I’ve seen it compared to Before Sunrise, the 1995 Richard Linklater flick in which characters played by Ethan Hawke and Julie Delpy meet on a European train and—through a night of walking and talking in a foreign city—discover one another’s souls. But there are some big differences too. At the end of Before Sunrise the lovers part, only to reunite decades later for two sequels. At the end of Southside with You, two colleagues at a Chicago law firm seem well on the road to getting married, and one of them will end up becoming the 44th president of the United States.

Yes, Southside with You chronicles the first purely social encounter of Michelle Robinson and Barack Obama. (He, a Harvard law student, is a summer intern at a big-name law firm, and she, officially his supervisor, is determined to keep their relationship all business.) Though their verbal give-and-take is the screenwriter’s invention, many of the details of their all-day outing, which includes a visit to an exhibit of African-American art and a screening of Spike Lee’s new and controversial Do The Right Thing, are apparently true. And some of the deep emotions they gradually reveal—involving her feelings about her career and his complex attitude toward his parents—can be found in news reports and in Obama’s Dreams from My Father. Midway through the film there’s a key scene in which they attend a meeting called by everyday black folks desperate to build a community center. It’s important to this movie in showing Michelle (as well as the audience) the uncanny abilities of this persistent young man who’s so determined to woo her, however frosty she may intend to be. Still, the film is most interesting when it’s just the two of them, bantering, bickering, airing their dreams.

What fascinates me is the fact that this is a love story featuring a sitting president. There’ve been lots of movies about U.S. chiefs of state, but most of them have been long out of office when they appear on the screen. Probably the president most often depicted in Hollywood movies is Abraham Lincoln, who’s featured in everything from the original Birth of a Nation to Spielberg’s masterful Lincoln. Most films in which he appears focus on the Civil War, but John Ford’s 1939 Young Mr. Lincoln tells the story of a young man (played by Henry Fonda) discovering his talent for law and finally deciding to run for political office. Lincoln’s future wife Mary Todd is a character in the Ford film, but so is Lincoln’s legendary lost love, Ann Rutledge.

The union of Franklin and Eleanor Roosevelt, seemingly a mismatched duo, is one that has long intrigued many Americans. But the TV miniseries dealing with their courtship and marriage, Eleanor and Franklin, did not appear until 1976, long after both were dead. I’m not sure I’d want to see the re-enacted wooing of George and Barbara Bush (dull?), nor that of John and Jacqueline Kennedy (disturbing?) on screen. My colleague Will Swift, distinguished president of the Biographers International Organization, has published Pat and Dick: The Nixons, An Intimate Portrait of a Marriage. Though most screen depictions of Nixon make him into a villain or a buffoon, Will’s book has persuaded me that the awkward Dick’s courting of glamorous Pat might lend itself to an interesting film. But a portrait of the Clintons (or the Trumps) finding love—that’s a bit too colorful for me.

Published on September 02, 2016 11:10

August 30, 2016

Love Stories; Life Stories: A Farewell to Gene Wilder and Arthur Hiller

I’m remembering two giants we’ve lost in the last two weeks: Gene Wilder and Arthur Hiller. Life, sad to say, isn’t fair. True, these gentlemen lived long and prospered. Wilder was 83 when he passed away, and Hiller was a ripe old 92. They were admired by the public and by their peers in that most fickle of industries, show biz. And yet their later years were clearly tough for them both, as well as for those who loved them.

I was first aware of Gene Wilder in 1967, in one of the most brilliant little sequences in an altogether brilliant movie, Bonnie and Clyde. He and his lady friend are canoodling on a small-town verandah when the Barrows gang audaciously steals his car, parked at the curb. In a series of wacky reversals, he and Velma pursue the outlaws, only to find themselves ordered at gunpoint into the stolen vehicle. For a while they get along famously with their abductors, sharing snacks and telling jokes. Then he happens to let slip his occupation—undertaker—and the mood dramatically shifts.

From that auspicious beginning, Gene Wilder went on to do unforgettable work for Mel Brooks, as Leo Bloom in The Producers, the Waco Kid in Blazing Saddles, and (best of all) the grandson of the famous Victor Frankenstein in Young Frankenstein. (Who can forget his “Puttin’ on the Ritz” song and dance routine with the monster? I’m told this was Wilder’s idea, vetoed by Brooks until he saw how well it played.) He also, as a mysterious candy maker named Willy Wonka, played a major role in the childhoods of many youngsters I know. In addition, he was part of an unlikely duo with Richard Pryor in both Silver Streak and Stir Crazy, zany films that made the two men Hollywood’s first successful interracial comedy team.

Along with all the fun, Wilder faced heartbreak, notably in his short-lived marriage to Gilda Radner, who died of ovarian cancer after less than five years of wedlock. He worked hard to raise money for cancer awareness, and slowly segued from acting into writing. But, tragically, it was complications from Alzheimer’s disease that claimed him on August 29, 2016.

Arthur Hiller was a director, not an actor, and so his face was not as familiar as Wilder’s, with its flyaway blonde curls and innocent blue-eyed gaze. Hiller actually directed Wilder and Pryor in Silver Streak, and was also known for a wide array of hit comedies and dramas, including The Hospital, Plaza Suite, and The Man in the Glass Booth. His favorite of his own films came early in his career, 1964’s wryly anti-war The Americanization of Emily, starring Julie Andrews and James Garner and based on a Paddy Chayefsky screenplay. But of course he remains best-known for the most schmaltzy film of its era., Love Story may be ripe for parody but it also earned Hiller an Oscar nomination as Best Director of 1970. Dedicated to his industry, he served as president of the Directors Guild and of the Motion Picture Academy, while also being active on the National Film Preservation Board.

I met Arthur Hiller in his later years, and was saddened to learn that macular degeneration was preventing him from making—or even watching—movies. In the last year, I caught a glimpse of him at the dentist’s office: he was essentially blind. A poignant outcome for a gentle soul dedicated to the motion picture medium. He passed away less than two months after his wife of 68 years. So I guess he knew what a Love Story was all about.

Published on August 30, 2016 12:15

August 26, 2016

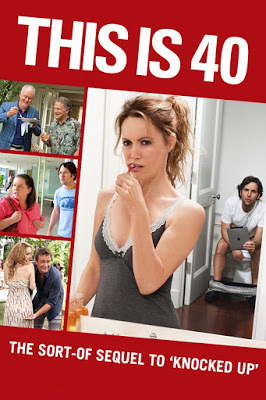

Judd Apatow’s Home Movie: “This Is 40”

I’ve been living in Judd Apatow’s world quite a bit lately. In the line of duty (don’t ask!), I’ve watched several of Apatow’s screen comedies, including Superbad, the great Knocked Up, and now This Is 40 (released in 2012). The latter two films feature a pair of SoCal Gen X’ers, Pete and Debbie, played by Paul Rudd and Leslie Mann. In contrast to Apatow’s familiar overaged adolescent characters, these two have all the trappings of upper-middle class adult life: a luxury home in Brentwood, pricey cars, two growing daughters who attend a posh school, lawyers and accountants. Still, the approach of middle age doesn’t make them feel stable and secure. Debbie obsesses over her looks and her sex appeal; Pete craves drugs and junk food. Both are desperate for sex, but real intimacy between them is rare, and it keeps getting thwarted (by the kids, by workplaces woes, by their personal neurotic anxieties). And their tenuous relationships with their fathers—both of whom have remarried and produced young children of their own—create additional tension.

What’s remarkable is that Apatow has closely modeled the marriage of Pete and Debbie after his own. Leslie Mann has been his actual wife for almost 20 years. The two daughters in both Knocked Up and This is 40 are played by Maude and Iris Apatow. In This is 40 they take on the roles of Sadie (age 13) and Charlotte (age 8), smart and sassy young girls who are frequently seen squabbling with their parents and with each other. Apatow has expressed some regret that, for the good of the project, Maude was required at one point to lash out at her screen mom and dad with plenty of f-bombs. No, he wouldn’t want her talking that way at home, no matter what language she hears from her elders. But—on behalf of his story line—he needed a shocking verbal explosion from her in the film. Not so nice for a parent to hear his young daughter cussing like a sailor. But hey, that’s show biz.

Even more remarkable than casting his own children is the fact that Apatow has been willing to dig deep into the daily facts of his own marriage. With the full cooperation of Leslie Mann, whom he calls “the bravest actress I know,” he uses films like This Is 40 to reveal the little secrets of married life, like public farting, misplaced vanity, sexual dysfunction, and unappealing bathroom habits. (Pete, when feeling stressed, likes to sneak off to the toilet to play Scrabble on his iPad. Debbie, suspicious of his lengthy absences from family life, demands to see the evidence of his bowel movements, even though he quickly assures her that “I flush as I go.”) Apatow is quick to credit Mann with being forthright about the female perspective on intercourse, childbirth, and other body functions. And he manages, with apparent good grace, to film her in extremely intimate situations with a guy to whom she’s not married in real life.

In the published version of This Is 40, part of the Newmarket Shooting Script series, Apatow explains how much he enjoys having his family members appear in his projects: “I love them and like to see them everyday.” Will there be more Pete and Debbie movies? “There’s a part of me that wants to make a sequel every seven years, like Michael Apted’s Seven Up documentary series.” Since he admits to writing comedic but still serious screenplays in order to figure out aspects of his own life, I look forward to seeing what’s next on his agenda.

Published on August 26, 2016 11:42

August 23, 2016

In Good Company in Malibu, Where Folks Do the Darndest Things

So Rio 2016 has been put to bed. I admit I’m a sucker for the Olympic Games. Yes, I know all the problems as well as all the annoyances of the NBC primetime coverage. (How many times can anyone bear to watch a commercial in which a grown woman insults her elderly dad because his “How I Met Your Mother” stories are not as exciting as the Internet?) But televised sports continue to grab me because of their unrivaled spontaneity. It’s the surprises that I’ll remember, like Joseph Schooling from Singapore beating the best in the field in the 100-meter butterfly. And South Africa’s Wayde Van Niekerk, raised with the legacy of apartheid, setting a world mark in the 400-meter sprint. Not to mention U.S. women’s beach volleyball stars Kerri Walsh Jennings and April Ross, down and out after their sloppy semi-final loss to a Brazilian pair, coming back from a serious deficit to tame two more Cariocas (and the crowd) for a hard-fought bronze medal.

Our entertainment media claim to believe in spontaneity too. That’s the point of all those reality shows where supposedly ordinary people (like duck hunters and stage mamas and “real housewives”) say the darndest things. I’m dating myself when I remember back to Art Linkletter’s House Party and People Are Funny, shows in which everyday folks were manipulated into showing off their goofy side. Those were innocent programs: a Linkletter specialty well known to schoolchildren in the L.A. area was to invite a few kids onto the show and coax them into comic answers to his theoretically artless questions. But if the Linkletter programs and such later entertainments as Candid Camera can be considered innocent merriment, today we expect a raunchy bluntness that’s not exactly extemporaneous. The shows’ makers carefully seek out “average” folk who lack a filter, then dream up situations that encourage them to go berserk. And they’re hardly above (on competition-type shows) stacking the deck by choosing heroes and villains in advance. I know someone who was quietly removed from a major competitive show when she refused to become the designated bad girl, the one who lives to undermine the hard work of others. Unscripted? Think again.

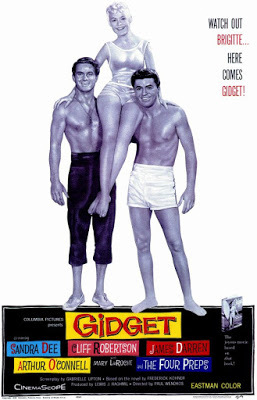

Which brings me, somehow, from Rio to Malibu, home of Gidget and Three’s Company. I had gone with friends to one of my favorite SoCal places, the Getty Villa. Built by zillionaire J. Paul Getty to match the style of ancient Rome’s Villa dei Papiri (which was destroyed by the eruption of Mt. Vesuvius in 79 A.D.), it houses a marvelous collection of Greek and Roman antiquities, beautifully displayed. Among the villa’s glories are its intricately patterned marble floors as well as the spectacular trompe l’oeilpaintings on the walls of its enclosed outer peristyle. Where did Getty’s team find the craftsmen to do this sophisticated work? Why, they were European emigrés, who’d made their living decorating the sets for Hollywood’s great Bible epics, like Ben-Hur and The Ten Commandments. Score another one for the influence of the film industry on Southern California cultural life.

Later, we had dinner in an outdoor Italian café that epitomized Malibu’s own dolce vita. This café too has a showbiz history: a birthday party for Barbra Streisand at which Andrea Bocelli led the singing, local resident Jim Carrey coming in several times a week to pretend to be a waiter. While we sat there, feeling blissful, the young women at the next table pulled out their phones, very excited. They’d spotted a Kardashian, complete with spouse and kids. In Malibu, even Kardashians are just part of the landscape.

The Getty Villa, with inlaid flooring

The Getty Villa, with inlaid flooring

Published on August 23, 2016 12:54

August 19, 2016

Rio 2016 – Boys Gone Wild?

Unfortunately—despite all the excitement involving female gymnasts, women’s beach volleyball, and an American sweep of the women’s 100 meter hurdles—the big news coming out of the Rio Olympic this week involves a quartet of American swimmers. Yes, their competition is over, but that hasn’t stopped them from making waves.

I admit I only know what I read in the papers, or hear from the lips of the unflappable Bob Costas. But it seems that medal-winner Ryan Lochte and three of his buddies went to a party hosted by French athletes. They had a lot to drink, then grabbed a cab at about 4 a.m. to return to their quarters. At some point the cab was accosted by fake Rio cops who pointed weapons at the athletes and robbed them of their wallets and valuables before fleeing into the night. That’s the story Lochte told his mom in the U.S., by phone, and soon it was all over the news media, serving as a reflection of the dangerous streets of Rio during the Olympic games.

No question that Rio can be dangerous. There’ve been several disturbing incidents in the last few weeks, including the mugging of the games’ head of security by men with knives immediately after the opening ceremonies. But this robbery of gold-medal American athletes caused a major headache for the Rio de Janeiro police force, which became determined to investigate. When they looked into the swimmers’ allegation, discrepancies began to appear. A security video that captured the foursome’s return to the Olympic Village called into question the timing of their taxi adventure. Not only that: they appeared to have on their persons some items they’d claimed were stolen hours earlier. Now three swimmers have been detained in Rio (two were pulled off an airline flight just before its departure) for questioning by the cops. And Lochte, already back home, also has some serious ‘splaining to do.

I feel sorry—for the swimmers, for the Rio police, for sports fans everywhere—that the excitement of the games has been marred by whatever is going on. Are the U.S. athletes liars? Contemplating this possibility, my movie-besotted brain latched onto several movies in which small lies have big consequences. There is, for instance, 1961’s The Children’s Hour, in which a young troublemaker at a girls’ school hints at a lesbian relationship between two teachers (played by Audrey Hepburn and Shirley MacLaine), leading to tragedy. In 2007’s Atonement, another young girl (remarkably played by 12-year-old Saiorse Ronan) is drawn by her own jealousy and sexual confusion to accuse an innocent man of attacking her sister.

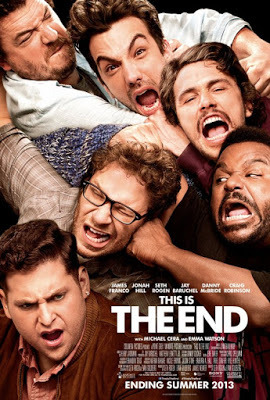

I don’t know, of course, if the four American men are liars. And their behavior, thank goodness, doesn’t seem to be leading to tragedy so much as embarrassment. They do admit they’d had too much to drink at that party. So I should probably be thinking about movies of a different sort. Like those of the last twenty years that feature overgrown male adolescents acting badly. Like Owen Wilson and Vince Vaughn in Wedding Crashers. Or the guys in The Hangover. Or Seth Rogen in anything he had a hand in writing, like Superbad or This is the End. Or that circle of slackers (Seth Rogen, Jonah Hill, Jay Baruchel, and company) in Knocked Up. Such movies—especially those overseen by Judd Apatow—can be really, truly funny. But the portrait they paint of young men with too much booze on their brains has some disturbing implications for our culture. At the movies we find them lovable. But in real life? Maybe not so much.

Since this was written, of course, the world has learned that this was indeed a case of American boys behaving badly, and then blaming others for their own misdeeds. Not exactly a proud moment for our nation.

Published on August 19, 2016 11:56

August 16, 2016

The Boys in the Boat: A Triumph of the American Will

Amid all the excitement about Michael Phelps, Simone Biles, and Usain Bolt, I suspect most Rio Olympics fans are not aware of the gold medal just won by the U.S. women’s eight crew. In fact, they are a dynasty unto themselves, having won eleven straight Olympic and world championships. Not with the same rowers, of course. A changing cast of smart, strong young women (8 wielding oars and 1 coxswain with a megaphone) has made sure the tradition of American dominance in women’s crew continues. The average armchair sports buff, though, is probably not paying attention.

But I’ll bet Daniel James Brown is thrilled. Brown is the author of one of the most exciting books I’ve read in a long time, The Boys in the Boat. Its subtitle: Nine Americans and Their Epic Quest for Gold at the 1936 Berlin Olympics. The “boys” were a hardscrabble team from the University of Washington, who had to overcome many hurdles on their way to Germany. Brown, a Seattle resident, was lucky to stumble upon their story, and to get to know the few surviving teammates. His book is an inspirational story of survival through grit and pluck, set at a perilous moment in world history.

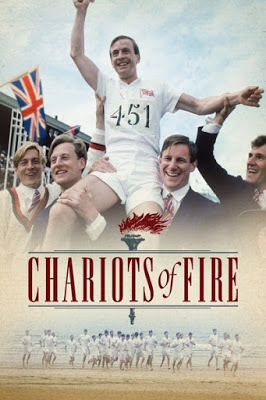

The top Oscar-winner from 1981 was Chariots of Fire, a stirring real-life tale about runners at the 1924 Paris Olympics. Its focus was on two outsiders on the British men’s team—a Jewish immigrant’s son and a devout Scottish Christian—who struggled to find acceptance among their aristocratic teammates, most of whom hailed from Britain’s elite (and snooty) universities. In The Boys in the Boat, there’s something of the same social tension. It’s the Depression era, and the Pacific Northwest young men, the sons of lumberjacks and dairy farmers, are having a tough go just coughing up their school fees. But hard times have honed their desire to win, and a brilliant coach named Al Ulbrickson proves to be a master at shuffling line-ups and making sure these tall, sometimes awkward collegians function as a unit. There’s also a master boatbuilder with the charming name of George Lyman Pocock who sees the poetry of rowing, and is able to impart it to rough-hewn young stalwarts with more practical matters on their minds.

On the road to Berlin, Ulbrickson’s team first had to defeat their arch rivals at the University of California. Then it was on to the east coast, where they felt abashed in the company of well-heeled Ivy Leaguers, for whom rowing was a longstanding tradition. If they were intimidated by American bluebloods, they felt even more so when competing against powerhouse British teams. This was all good practice for their arrival in Berlin, where Hitler and his Nazis was determined to prove Aryan superiority through sport. Brown details the spectacular venues provided by the host nation, as well as the efforts made by Nazi Germany to hide its racist ideology and put out the welcome mat to athletes from all over the world.

Rowing sports were a huge deal in that era, and fans near and far gathered in front of radios to hear the outcome of the men’s eight. The stands were packed with enthusiasts, and Hitler himself sat in the VIP box to cheer his country’s crew team on to victory. But it didn’t happen. Somehow the scrappy Americans overcame all obstacles to eke out a win. German filmmaker Leni Riefenstahl, who’d been assigned to document the 1936 Olympics for posterity, captured the race with her cameras. But in her classic 1938 documentary, Olympia, the victory of the American crew had no place.

The Boys in the Boat has been optioned by the Weinstein company for filming, but there are still no concrete details about an upcoming production. I do know a young actor, also a gifted rower, who’d be perfect for a major role. (Josh Pence, I’m looking at YOU!) Meanwhile, we can watch bits of Riefenstahl’s footage on YouTube, as in this little documentary, made to inspire female rowers.

Published on August 16, 2016 11:52

August 12, 2016

"Superbad": A Long Way from Andy Hardy

I’m much too young for the Andy Hardy movies, which flourished just before and during World War II. Andy (played by Mickey Rooney) was an amiable small-town adolescent. He was always getting into scrapes involving money and girls, then afterward learning the error of his ways through chats with his father, the kindly but upright Judge Hardy. This was an adult’s-eye view of what growing up ought to be.

Since then, the high school years have been presented in vastly different lights. The 1950s saw the rise of teen problem films, including 1955’s Blackboard Jungle and Rebel Without a Cause, that spotlighted young people who felt isolated from the world around them. Teenage characters in these films -- Sidney Poitier’s Greg Miller and James Dean’s Jim Stark among them – were viewed with sympathy, even when they misbehaved. But these films left us feeling that help for these lost souls would come through interventions from good-hearted adults, like Blackboard Jungle’s dedicated teacher and Rebel’s remorseful father.

When George Lucas made American Graffiti in 1973, he pretty much wiped adults out of the picture of a small-town cruise night among a group of new high school graduates. The young people in this film deal with their problems among themselves, without adult interference. This approach had great appeal to the youthful viewers who were being courted by studios in the post-Sixties era. And American Graffiti has a winning frankness about the role of drinking, sexual attraction, and car culture in the lives of teenagers. Still, Lucas set his film back in time (“Where Were You in ’62?” was the film’s nostalgia-inducing catchline), and so the bad behavior we see on screen seemed slightly dated, even when the film was new.

In the 1980s it was John Hughes who captured the sense of what it’s like to be a high school student, in such widely popular films as The Breakfast Club, Pretty in Pink, and Ferris Bueller’s Day Off. Again, the focus is almost entirely on young people whose support systems among parents and teaches seem to have broken down. The Breakfast Club, especially, concentrates on deeply troubled teens whose campus misdeeds have led to official punishment. But nothing they’ve done (pulling a fire alarm, playing a prank, skipping school) seems, to our modern eyes, all that bad.

Then there’s 2007’s Superbad, which takes the misbehavior of graduating high school seniors a giant step further. The cringe-worthy acts of the two central characters and their friends seem to have the ring of contemporary truth, maybe because screenwriters Seth Rogen and Evan Goldberg started creating the project while still in their own teens, basing some of the shenanigans we see on screen on their own lives (and, I assume, their own fantasies). The seniors played by Jonah Hill (as Seth) and Michael Cera (as Evan) are not shown to be troubled in any dramatic way. Rather, they’re presented as realistically horny adolescents, obsessed with male and female body parts and stoked by the possibility of getting laid before they go off to pursue higher education. Says Seth, early on, “The point is to be good at sex before you go to college.”

As a way to pursue their goal of getting in the pants of some attractive classmates, they (and their doofus pal Fogell) get involved with a desperate scheme to stock Emma Stone’s graduation party with booze. Complications of course arise: a liquor-store robbery, some rogue cops, and teen sex foiled by drunken upchucking. My own high school days were much tamer. But I suspect my kids would feel right at home.

Published on August 12, 2016 11:17

August 9, 2016

Barbra Streisand: A Person Who Needs (Hollywood) People

For Barbra Streisand, this may be the best of times and the worst of times. At age 74, she’s just kicked off a new national tour with an acclaimed performance at L.A.’s Staples Center. The tour, modestly named “Barbra: The Music . . . the Mem’ries . . . The Magic!”, is designed to showcase a new duets album that goes on sale August 28. At the same time, the long-gestating new Barry Levinson film project, a reworking of the Broadway musical Gypsy, has once again lost its financing, and will not be starting production in fall as planned. Which means it’s more unlikely than ever that we’ll see Streisand play the iconic role of Mama Rose.

Gypsy, the 1959 Broadway hit that combined the talents of Jerome Robbins, Arthur Laurents, Jules Styne, and Stephen Sondheim, originally featured Ethel Merman as the indomitable mother of stripper Gypsy Rose Lee. It’s a role for a powerhouse singer as well as a great actress. The Hollywood “geniuses” behind the 1962 film version chose to cast Rosalind Russell, a Hollywood legend but not someone exactly known for her musical chops. (That’s one of many reasons the movie is barely remembered today.) In major stage and TV revivals, the part has gone to Angela Lansbury, Tyne Daly, Bette Midler, and Bernadette Peters. From what I’ve learned from Neal Gabler’s respectful new biography, Barbra Streisand: Redefining Beauty, Femininity, and Power , Mama Rose would be an ideal fit for Streisand. She certainly has the pipes for the job, as well as the combination of vulnerability and strength that the role demands.

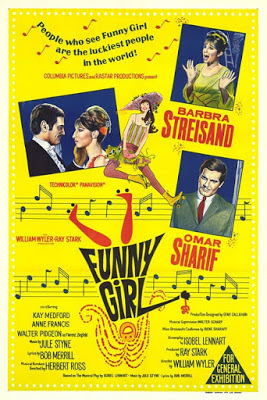

According to Gabler, Streisand’s goal was always to be an actress. She diligently studied the craft (fellow acting student Dustin Hoffman remembered her as “a hungry baby bird”), but of course it was singing that provided her with a breakthrough moment. It came with Broadway’s Funny Girl, the musicalized story of Ziegfeld Follies entertainer Fanny Brice. I learned from Gabler that director Jerome Robbins lobbied for Anne Bancroft to play the leading role. Others in contention included Broadway stalwart Mary Martin and comedienne Carol Burnett. Gabler describes Funny Girl as “a Jewish story of an outsider trying to win acceptance in a world of beauty and glamour wrapped around the story of romance doomed by a driven Jewish woman’s success.” Which made it the perfect role for Streisand, who shared both Brice’s ethnicity and her profound discomfort with her less-than-All-American looks. Writes Gabler, “Certainly others could have played Brice. But only Streisand had lived Brice.”

The Broadway success of Funny Girl took Streisand to Hollywood, where she promptly became an Oscar winner. Thereafter she appeared in some not-entirely-suitable roles, like that of the middle-aged lead in Hello, Dolly! Gabler himself is most partial to The Way We Were, which he sees as revealing Streisand’s own personal strengths and weaknesses. The film’s failed romance with the character played by Robert Redford shows Streisand’s Katie paying a price “for her moralizing, for her perfectionism, for her gutsiness, for her ardency, for her stridency, for her lack of conformity—for all the things her fans had come to love about her and about her characters. She pays a price to be Barbra Streisand.”

Of course Streisand has played many other movie roles, and has been gutsy enough to defy the Hollywood system by directing herself in Yentl, The Prince of Tides, and The Mirror Has Two Faces. All have suffered critical slings and arrows, but the lady marches on. Who can forget the way she was? And we have high hopes for what she is yet to be.

Published on August 09, 2016 16:35

Beverly in Movieland

I write twice weekly, covering topics relating to movies, moviemaking, and growing up Hollywood-adjacent. I believe that movies can change lives, and I'm always happy to hear from readers who'd like t

I write twice weekly, covering topics relating to movies, moviemaking, and growing up Hollywood-adjacent. I believe that movies can change lives, and I'm always happy to hear from readers who'd like to discuss that point.

...more

- Beverly Gray's profile

- 10 followers