Beverly Gray's Blog: Beverly in Movieland, page 97

August 5, 2016

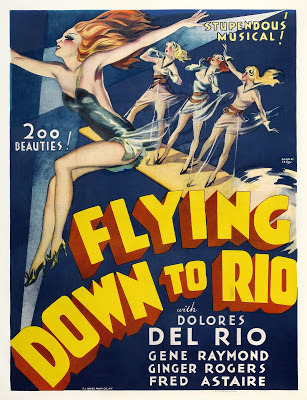

Flying Down to Rio for the Olympic Games

Today marks the kick-off of the Olympic Games in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Not that the path to these Olympics has been a smooth one. What with political turmoil, economic meltdown, crime in the streets, and garbage in the bay, the 31st Olympiad may not exactly be a triumph. (Then there’s the Zika virus, and the Russian doping scandal, and the threat of terrorism: I could go on and on.) But why not think positive? Rio is known to be a beautiful city, despite it all, and who can resist the meeting of the world’s greatest athletes? And, come what may, I’ll always have the Rio of the movies.

The first movie I know that features at least a fantasy version of Brazil’s many charms is a 1933 pre-code musical from RKO, Flying Down to Rio. It stars (yup!) Dolores del Rio as part of a romantic triangle, but is more famous for introducing the great duo of Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers. When Astaire and Rogers slither through the Carioca, their foreheads touching, screen history is made. If Rio seems the home of romance in this film, it looks even sexier in a full-color romp called That Man from Rio, a lively French spy spoof featuring authentic Brazilian locations and the delightfully rumpled Jean-Paul Belmondo. Twenty years later, the city of Rio was featured in a mild American sex comedy, Blame it on Rio. (Though Michael Caine, director Stanley Donen, and writer Larry Gelbart were all involved, it didn’t make many waves.)

Brazil of course has its own active film industry. Most of the titles are unfamiliar, but some have definitely made their presence felt on the international circuit. One is a sexy comedy from 1976: Dona Flor and Her Two Husbands. This story of a woman torn between a proper gentleman and a sexy layabout (who returns to her as a ghost) made a star of Sonia Braga. Several of the most highly regarded Brazilian films tackle life in the country’s picturesque but toxic slum neighborhoods. One is Pixote (1981), which focuses on a ten-year-old runaway struggling to survive on the streets of São Paulo. Its director, Hector Babenco, would later go on to direct Sonia Braga, Raul Julia, and the Oscar-winning William Hurt in an inventive prison drama, 1986’s Kiss of the Spider Woman. In 2002, Fernando Meirelles and Kátia Lund directed an even more brutal story, one that features Rio’s rival street gangs, Called City of God, it captures the toll taken on the lives of young people who grow up in a violent culture.

But I want to end on gentler note, with an Oscar-winning film that has always symbolized Brazil for me. Black Orpheus (originally Orfeu Negro) dates all the way back to 1959. Its director, Marcel Camus, was French, but in staging the ancient Greek love story of Orpheus and Eurydice (and setting it against the phantasmagoric excitement of Carnaval), he went to the streets of Rio in search of potential actors. Interestingly, several he found were athletes. Breno Mello, who played Orpheus, was a soccer player. And Adhemar da Silva, in the key role of Death, had won Olympic gold medals in the triple jump in 1952 and 1956.

Orpheus in the Greek original was a musician, and it is the film’s music that most sticks with me now. Antônio Carlos Jobim was involved, and guitarists the world over now make Theme from Black Orpheus part of their repertoire.

Black Orpheus was the very favorite film of Barack Obama’s mother. Who knows how it helped change history?

Anyway, let the games begin!

Published on August 05, 2016 12:24

August 2, 2016

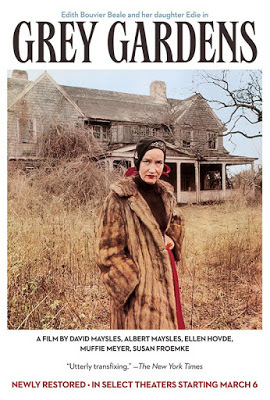

Grey Gardens Lives On: A Tribute to the Maysles Brothers, and some others

Film at its best can confer immortality. Such is the case with Grey Gardens, a 1975 documentary by Albert and David Maysles that chronicles in direct-cinema style (closely akin to the French cinéma vérité) the daily lives of a mother and daughter who eked out a precarious existence in a decaying mansion that was once an East Hampton showplace. The startling case of Big Edie and Little Edie Bouvier Beale came to light in the early 1970s, when newspapers began reporting that the one-time socialites were living in squalor, surrounded by cats, fleas, and garbage. The story made headlines because Edith Bouvier Beale (“Big Edie”) was the aunt of Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis, and her daughter Little Edie was Jackie’s first cousin. A large donation by Jacqueline and Aristotle Onassis helped replace the mansion’s defunct furnace and plumbing systems, but the two women continued to live in eccentric squalor until Big Edie’s death.

The Maysles brothers’ documentary gave viewers a first-hand glimpse of the two Edies, who are viewed by some as pathetic and by others as heroic in their determination to make their own life-choices. Both had artistic aspirations: Big Edie aspired to be a singer, and in the mansion’s heyday insisted on performing at parties; Little Edie, in her early years, had some success as a New York fashion model and dreamed of a Hollywood career. (She also dreamed of marrying a dashing young man of the likes of Joseph Kennedy Jr., but her brief engagement to the eldest Kennedy son was apparently one of her many fantasies.) In later years, when all of her body hair fell out due to alopecia, she adopted a headscarf look that made its own unique fashion statement.

On the heels of the Maysles’ film, which was featured at the Cannes Film Festival in 1976, there was much additional media attention to the Beales. A 78-minute interview with Little Edie at Grey Gardens appeared in 1976. The two Beales inspired photo-spreads in magazines like Vogue, as well as additional documentaries in this century, including Ghosts of Grey Gardens. Today there’s actually a so-called Grey Gardens lifestyle legacy brand, created by a family relative. It features housewares and accessories supposedly based on Little Edie’s fashion flair in the days before she succumbed to total eccentricity.

Grey Gardens also became a much-honored 2009 HBO made-for-TV movie, starring Drew Barrymore and Jessica Lange, who won an Emmy for her role. And a Broadway musical based on the lives of the two Beales played 300 performances on Broadway, from November 2006 to July 2007. Recently revived in a new production with Rachel York and Betty Buckley, it is now playing at L.A.’s Ahmanson Theatre, where I had a chance to see it two nights ago. Its score doesn’t make you come out humming, but it remains a fascinating exploration of a symbiotic relationship that’s as mysterious as it is all-consuming. This new production pays tribute to the original work of the Maysles brothers by introducing two filmmaker characters haunting several scenes with their cameras and boom mikes, and also by incorporating what looks to be actual Maysles footage projected onto the set.

To be honest, I for one find the Beales to be disturbing rather than enchanting. But I’m glad to have gotten to know more about these puzzling but unforgettable women. By the way, Grey Gardens, the estate, is proving to have some immortality of its own. The elder Edie, though impoverished, refused to sell, but Little Edie sold it to journalism’s Ben Bradlee and Sally Quinn, who’ve lovingly restored it to its past glory.

Published on August 02, 2016 13:08

July 29, 2016

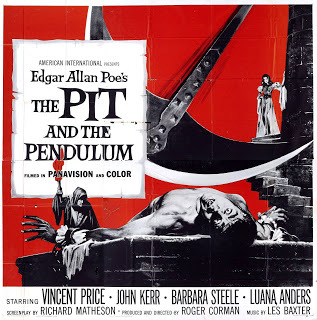

Roger Corman Dives into the Pit (and the Pendulum)

This year The Pit and the Pendulum is 55 years old. And Roger Corman? He’s 90. I saw both the film and its director this past week, in the posh Goldwyn Theater of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. It was part of the “Archival Revival” series, celebrating 25 years of the Academy Film Archive. The film I watched was a beautiful 35 mm. print, one of several Corman flicks that the Academy has lovingly restored. (Others include The Intruder, The Student Nurses, Rock ‘n’ Roll High School, and Ron Howard’s debut film as a director, Grand Theft Auto. Coming soon: House of Usher and X—The Man with X-ray Eyes. )

This year The Pit and the Pendulum is 55 years old. And Roger Corman? He’s 90. I saw both the film and its director this past week, in the posh Goldwyn Theater of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. It was part of the “Archival Revival” series, celebrating 25 years of the Academy Film Archive. The film I watched was a beautiful 35 mm. print, one of several Corman flicks that the Academy has lovingly restored. (Others include The Intruder, The Student Nurses, Rock ‘n’ Roll High School, and Ron Howard’s debut film as a director, Grand Theft Auto. Coming soon: House of Usher and X—The Man with X-ray Eyes. ) Before the screening, an Academy representative interviewed a genial Roger, who looked and sounded terrific. His only concession to his advanced years was that he now uses a cane to walk. He talked smartly about the advantages and disadvantages of CGI, which he noted (based on his experience with films like the upcoming Death Race 2050) considerably slows down the editing process. Given that his early movies took only 10 days to shoot, and that the more elaborate Poe films (like The Pit and the Pendulum) took a mere 15, Roger is a man accustomed to speed. He also discussed his famous alumni, put in a plug for wife Julie’s success with family films, and explained how he brought art-house masterpieces by the great Ingmar Bergman to drive-in movie theatres. Bergman wrote a letter of thanks, explaining that he’d always wanted to reach a wider audience. It’s a letter, nicely framed, I’ve seen many times on the wall leading into Roger’s office.

But a man in his 90s may be excused a few memory lapses. Prompted by the interviewer, he talked about his Stanford days, when he wrote movie reviews for the campus paper. He remembered giving John Ford’s My Darling Clementine an especially strong review. Sorry, Roger! My research for my biography, Roger Corman: Blood-Sucking Vampires, Flesh-Eating Cockroaches, and Driller Killers, led me to read through all the Stanford Dailies from Roger’s time on campus. As a sports editor, he wrote regular columns, but I never came across a movie review with his name on it. It’s possible that one or two slipped by me, but My Darling Clementine didn’t open until around the time he graduated.

No matter. I enjoyed seeing The Pit and the Pendulum on the big screen. It is far from my favorite of the Poe films: I give that crown to the macabre and elegant Masque of the Red Death, made in England on more sumptuous sets. Yes, I can see why that lethal pendulum would have scared the daylights out of youngsters years ago. But to me Pit’s storytelling seems convoluted and much of its acting stiff. Some in the Academy audience actually laughed at the highly theatrical (OK, hammy) acting style of Vincent Price. When I recently screened Masque for a community event, no one had the slightest inclination to titter: some who had assumed it would be campy expressed surprise afterward at the movie’s power.

One big plus in The Pit and the Pendulum was the reliably creepy Barbara Steele. I also much enjoyed seeing Luana Anders on screen. Decades after this film was made, she had modest success as a screenwriter. I worked with Luana on the script for Fire on the Amazon (1993), a jungle drama best remembered for a hot nude scene featuring a then-unknown Sandra Bullock. Luana and I talked about how her name often showed up in crossword puzzles. She loved the recognition.

Published on July 29, 2016 12:37

July 26, 2016

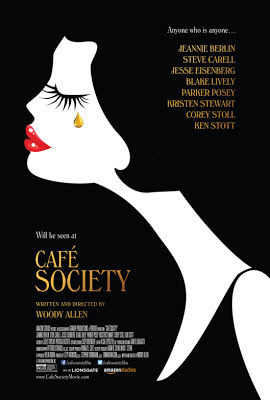

Woody Allen’s “Café Society” -- Where Middlemen Rule

Woody Allen’s latest, Café Society, is a tragicomic look at love and regret, set on the fringes of showbiz. The film, gorgeously photographed by three-time Oscar-winner Vittorio Storaro, gives the warm glow of nostalgia to the period in which (while the working class struggled to put food on the kitchen table) Hollywood movers and shakers lived the high life. It’s a world where outsiders can quickly become insiders, but may lose something important in the process. Jesse Eisenberg, as a gawky New York kid who tries going Hollywood, makes a perfect neo-Woody surrogate, and Kristen Stewart has a fresh loveliness that explains why she gets under men’s skin. But I want to focus on Steve Carell, playing superagent Phil Stern. He’s a Hollywood success story, a wheeler-dealer who’s always too busy juggling calls from Ginger Rogers and Adolph Menjou to complete a conversation with whoever’s right in front of him.

I’ve got agents on the brain right now, because I’ve just finished reading a fascinating business book by my friend and colleague, Marina Krakovsky. In The Middleman Economy: HowBrokers, Agents, Dealers and Everyday Matchmakers Create Value and Profit,she argues that we are all middlemen (or, I suppose, middlewomen) in one way or another, whether we work in business, in education, as realtors or as nannies. Using lots of real-world examples, she cleverly categorizes various ethical middleman functions as The Bridge (“Spanning the Chasm”), The Certifier (“Applying the Seal of Approval”), The Enforcer (“Keeping Everyone Honest”),. The Risk-Bearer (“Reducing Uncertainty”), The Concierge (“Making Life Easier”), and The Insulator (“Taking the Heat”). Discussing this last category, she introduces powerful sports agent, Drew Rosenhaus, whose abrasive personality—as used in support of his many star clients within the National Football League—inspired an important character in the film Jerry Maguire. Rosenhaus makes no apologies for his outrageous verbal attacks on team management. He sees these as serving his clients’ interests: on their behalf he can take the heat for his own rants, saving the athletes from burning their bridges with their teams.

Marina deals with the positive outcomes that result from middlemen’s maneuvering. Leave it to Hollywood, of course, to focus on situations in which middlemen find they can’t stomach their in-between position. George Clooney has made something of a specialty of portraying the man in the middle, in such films as Michael Clayton (2007) and Up in the Air (2009). In both he plays a fixer charged with smoothing over something that’s illegal, or at least profoundly unpleasant (like the firing of a firm’s longtime employees). Eventually, of course, his character sees the light. Then there’s Tom Hanks, another of Hollywood’s traditional good guys, who in Bridge of Spies (2015) reluctantly takes on the task of defending a Soviet spy in an American courtroom, and somehow emerges unscathed by the process.

Steve Carell’s agent-character in Café Society doesn’t seem to be doing anything that’s either illegal or profoundly distasteful. But there’s the acute sense that his in-between position has turned him into both a sycophant and a poseur, one who’s forever sucking up to those above him and lording it over those who haven’t reached his level. He gets richly rewarded (romantically and every other way), but perhaps loses his soul. Just like another of the film’s characters: his brother Ben. Ben is a Brooklyn mobster who takes care of business when someone needs to be taught a lesson. If you need help with a noisy neighbor, for instance, just say the word. But I don’t think Marina Krakovsky has this kind of middleman in mind.

Published on July 26, 2016 15:19

July 21, 2016

How Garry Marshall Made Sure that “Happy Days” Stayed Happy

I met the late Garry Marshall in 2004. It was backstage after the taping of a reunion show celebrating the thirtieth anniversary of one of Marshall’s classic sitcoms, Happy Days. Because I’m the author of Ron Howard: From Mayberry to the Moon . . . and Beyond, I was invited by the founder of the international Happy Daysfan club, who’d flown all the way from Milan, Italy for the occasion. Yes, Happy Days—that amiable series about growing up in the 1950s—has loyal fans all over the globe. And several of them had made their way from Europe to L.A. for the occasion.

Those fans saw far more than just a taping. (And what a taping it was, attended by Ron Howard, Henry Winkler, Tom Bosley, Marion Ross, Erin Moran, and many others, all reminiscing about a show they loved.) The reunion kicked off with a softball game, much like those overseen by Marshall in the days when the series was on the air. Marshall, the ultimate sports fanatic, formed the team to foster esprit de corps among cast and crew. They started out playing on weekends in an entertainment industry league, and eventually came to spend hiatus periods touring the world under USO auspices, playing exhibition games against American troops in Germany and Okinawa. (Ron Howard, a natural athlete, excelled as a batter and fielder. He also mentored Henry Winkler, who surprised himself by becoming a competent pitcher. Their on-the-field camaraderie helped in calming a delicate situation on the set: Howard was supposed to be the show’s featured player, but it was Winkler, as the Fonz, who became the breakout star. Somehow the two survived the tension of their unequal status and became lifelong best friends.)

Part of the reason that Happy Days retained its family feeling, year after year, was that Garry Marshall was firmly in charge. Marshall, one of Hollywood’s truly nice guys, ran a set as though he were the genial host of a party. Not that he allowed for sloppy work, but he always made sure that his projects were true collaborations. Rich Correll, who worked on the Happy Daysproduction team, told me how Marshall introduced himself to every new member of the cast and crew: “Look, yes, I’m Garry Marshall and it’s my show, but if you have a better idea for a joke that we’re pitching, come up and give it to me. . . . If you can fix it, you can tell me anything. Now you might not have the right fix, but don’t be afraid to tell me.” It was a lesson that Ron Howard quickly took to heart. Once Howard became a director in his own right, he chose to adopt the same policy. Those who work with him for the first time are skeptical at first: many directors talk a good game about collaborative effort. Truth be told, Howard (like Marshall) really practices what he preaches.

Marshall’s obits have not mentioned another of his projects, one that touches my heart. As a lifelong theatre buff, he joined with his daughter to build the Falcon Theatre, a 130-seat space in Burbank, California, not far from several major studios. It operates year-round, presenting Hollywood professionals in comedies and dramas, while also hosting a number of offerings for children. Sometimes Marshall himself would step in as director, as he did for Happy Days: A Family Musical a few years back. One of Marshall’s favorite TV characters, Sgt. Ernest G. Bilko, used to say, “The bigger they are, the nicer they are.” In Marshall’s own case, how very true.

Published on July 21, 2016 12:24

July 19, 2016

Evelyn Nesbit: The Girl on the Red Velvet Swing and the Crime of the Century

This poster is adapted from a famous photo of Evelyn Nesbit

This poster is adapted from a famous photo of Evelyn NesbitAmerican Crime Story’s “The People Vs. O.J. Simpson” has just been nominated for a whopping thirteen primetime Emmys. Hardly surprising, given the power of the murder trial we couldn’t stop watching in 1994-1995. The possibility that football-star-turned-actor O.J. Simpson had murdered his ex-wife encompassed so many key American issues: race, sex, celebrity. No wonder it was often labeled the Crime of the Century.

Back on June 25, 1906, another murder equally galvanized the nation. It evoked all the tension surrounding the shifting social patterns of the brand-new twentieth century. This was a time when old moral and aesthetic codes were breaking down, and new wealth was taking over the social establishment. Somehow the murder of New York architect and bon vivant Stanford White by Harry Thaw of Pittsburgh, prodigal heir to his father’s industrial millions, came to exemplify the obsessions of the new era. Naturally there was a woman at the center of the story.

She was Evelyn Nesbit, a beautiful and very young (age 22) photographer’s model and Broadway chorus girl. She was also Harry Thaw’s wife. As Paula Urburu makes clear in American Eve: Evelyn Nesbit, Stanford White, the Birth of the “It” Girl and the Crime of the Century , Evelyn had settled in New York at age fourteen with her widowed mother and troubled brother. Since Mamma had no plan for supporting the family on her own, Evelyn’s precocious beauty became the little family’s meal ticket. At fifteen, appearing on Broadway and living a life that was mostly unsupervised by her feckless mother, Evelyn met the dashing Stanford White. He—a major celebrity responsible for such landmarks as the original Madison Square Garden—quickly took her under his wing. At first he was a welcome father figure. Then he drugged and raped her. With few other options available, she chose to overlook his sinister act and became his willing mistress, though she eventually moved on when he began turning to new young conquests.

Harry Thaw fell hard for Evelyn. Many other stagedoor Johnnies had, but the unstable Harry was obsessed with wreaking vengeance on Stanford White, even before he met her. He wormed out of Evelyn the story of how White had “despoiled” her innocence. Now knowing a truth she had successfully kept hidden, Thaw raped and brutalized her himself. Somehow he eventually got her to marry him in a private ceremony. (The bride wore black.) Then one evening as they attended a rooftop performance at White’s Madison Square Garden, he shot White at close range. Somehow he expected to be acclaimed a hero for defending his wife’s sacred honor.

During several trials, Evelyn was forced to describe aloud the indignities she’d suffered (as well as providing titillating details about cavorting on White’s private red velvet swing). The public couldn’t get enough of it. A film, Rooftop Murder, had been rushed into production by Thomas Edison’s studio a mere week after the tragedy occurred. Later there would be other films and stage productions, some financed by Harry Thaw’s own family, who were bent on selling their version of him as a crusader for American womanhood.

Years later, an impoverished Evelyn herself acted in films that were essentially versions of her eventful life. And in 1954 she actually sold her story to Hollywood. (In The Girl in the Red Velvet Swing she was portrayed by newcomer Joan Collins). Milos Forman’s film of E.L. Doctorow’s Ragtime raises Evelyn from a cameo role into a major player. As a forerunner of today’s young publicity hounds, she’s a dramatic example of how life in the spotlight can destroy innocence and beauty.

Published on July 19, 2016 13:29

July 15, 2016

Lin-Manuel Miranda Puts the Ham in Hamilton

Don’t get me wrong – I love this guy. Aside from being a great talent, Lin-Manuel Miranda has shown multiple times that he’s a gentleman and a scholar. Scholar? Well, Miranda got his inspiration for the Broadway phenomenon Hamilton when he toted along on a family vacation Ron Chernow’s hefty and erudite 2004 biography of Alexander Hamilton, founding father of the U.S. financial system. Chernow came on board as an historical consultant to the musical, and he has praised Miranda’s uncanny ability to synthesize complex ideas into catchy hip-hop lyrics. Somehow Miranda has managed to make the tale of our country’s founding so vital and interesting that whole generations of school kids (and their parents) are being turned on to the ins and outs of America’s past. I deeply respect the show’s management for working hard to give youngsters the opportunity to step into history.

Along with writing music, book, and lyrics for the Pulitzer and Tony-winning Hamilton, Miranda of course played the title role. Here’s how he shows his gentlemanly side: this past week, as he stepped down from the Broadway cast, he made it a point of loudly praising his understudy and now replacement, Javier Muñoz. Introducing Muñoz to the press, he emphasized that throughout the show’s evolution the two had created the role together. There aren’t many actors who would be so generous in sharing credit..

I first became aware of Miranda in 2008 when I saw his earlier Tony-winning production, In the Heights. Far less ambitious than Hamilton, it’s a somewhat predictable tale of the Manhattan neighborhood of Washington Heights, a place where many colorful ethnicities meet and mingle. I had mixed emotions about the show, despite its lively Latin music. But Miranda (as an amiable narrator-figure named Usnavi) was a rapper’s delight. Then there were the years when he popped up on the Tony Awards broadcast with on-the-spot freestyle salutes to the evening’s victors. Wow!

Like any actor trying to make a living, Miranda could also be seen in modest television roles, on shows like House, Modern Family, and How I Met Your Mother. But the acclaim he’s gotten for Hamilton (which also includes a MacArthur “Genius” grant) has assured him of a more starry second act. It’s been pointed out of late that he’s a prime contender for the fabled EGOT designation, which recognizes those legendary few who’ve won all four of the entertainment world’s prime honors: the Emmy (for work in television), the Grammy (given by the recording industry), the Oscar (which acknowledges cinema greats), and the Tony (for Broadway excellence). At the moment Miranda lacks only the naked bald guy. But his future in the movie industry is looking brighter by the moment.

As a writer, he’s already contributed a song for the cantina scene in the most recent Star Wars. Soon afterward he was tapped by Disney to write songs for this year’s Polynesian-themed animated feature, Moana. So, given Disney’s long track record in the Best Song Oscar category, a statuette may not be far off. Then there’s his acting career. He’s been signed to cavort opposite Emily Blunt in a musical Mary Poppins sequel, due out in 2018.

Another lovely aspect of Lin-Manuel Miranda is that he’s a true family guy. When he married his sweetheart, Vanessa, in 2010, he prepared a little something to surprise her during the wedding banquet. I’m told it took a month of planning and the secret participation of many friends and family members. Luckily for us, he posted the results on YouTube. What can I say, other than “l’chayim”? (Only in America, right?)

<iframe width="560" height="315" src="https://www.youtube.com/embed/KgZ4ZTT..." frameborder="0" allowfullscreen></iframe>

Published on July 15, 2016 10:58

July 12, 2016

Star Trek at the Hollywood Bowl: Boldly Going Where Many Men Have Gone Before

There’s nothing quite like the Hollywood Bowl on a midsummer’s evening. When the stars are twinkling overhead, it’s a remarkable place from which to soar into space with Star Trek. The Bowl is a magical venue: 17,000 Angelenos can dine under the twilight sky, then listen to lilting classical music or lively pops while watching the Hollywood Sign fade into oblivion as the sun descends. Because of its location and its landmark status, the Bowl (which opened in 1922, but has been subject to countless re-models) has been featured in a good many movies.

In recent years, the Bowl has also played host to a number of movie screenings. Some of these events have been kitschy, like the inevitable Sound of Music singalong. But, in a city where classical musicians often moonlight recording scores for movie studios, it’s also logical that the Bowl salute the work of great film composers. This past week, the hometown band in residence was the estimable Los Angeles Philharmonic, which uses the Bowl as its summer residence. During two popular screenings of Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone, the L.A. Phil was on stage playing John Williams’ majestic score. I missed that, but took advantage of the weekend to have fun with the 2009 Star Trek prequel. David Newman, a busy film composer in his own right (son of Hollywood’s musical great Alfred Newman and cousin of Randy) conducted the stirring score by Michael Giacchino, who was present to introduce the film.

Giacchino’s movie credits are impressive: he’s provided the music for a host of Pixar films (Ratatouille, Up) as well as entries in the Mission: Impossible and Jurassic Park franchises. Speaking to an appreciative crowd, he told a charming story about his own childhood fascination with movie soundtracks. When he was a kid, he saw in theatres such child-friendly blockbusters as Star Wars, The Sting, and Raiders of the Lost Ark. He came home wanting to see them again and again, but in a pre-VCR era this wasn’t often possible. That’s why he looked to soundtrack albums to help him relive the pleasure he’d found on-screen. No wonder he became a composer of film scores.

In addition to the big screen descending from the band shell on the Bowl stage, there are also a several strategically-placed smaller screens, so that no one in the cheap seats can complain about missing out on a good view. It was on these multiple screens that Star Trek director / producer J.J. Abrams addressed the crowd. He noted the loss in the recent past of two important Star Trek personalities: the great Leonard Nimoy (who left this earth in February 2015) and young Anton Yelchin (Chekov in the prequel), who was killed in a freak accident less than a month ago). Fortunately, some Star Trek heroes live long and prosper: the ubiquitous and ageless George Takei was in the house, and enjoyed a big hand.

I got a kick out of the film, especially in the first half when cocky young hellraiser James T. Kirk (Chris Pine) and deep-thinking young Vulcan Mr. Spock (Zachary Quinto) definitely failed to see eye to eye. Both of course experienced personal tragedy early on. Then it got all mystical, with the appearance of an aged Spock (Nimoy) and some mumbo-jumbo about time travel. Obviously my Trekkie credentials are not in order, but at least I didn’t share the confusion of some in the cheap seats between Star Trek and Star Wars. Anyway, we cheered for the reconciliation of Spock and Kirk, and a good time was had by all.

Published on July 12, 2016 16:53

July 8, 2016

A Red-White-and-Blue Salute to Marjorie Merriweather Post

As we see July 4, 2016 in our rearview mirrors, I’m reminded of a woman whose life seems to me pure Americana. It was on my last trip to Washington DC that I discovered Marjorie Merriweather Post, by way of a visit to her exquisite DC estate, Hillwood. Marjorie was the daughter (and only child) of C.W. Post, a midwesterner who started out inventing and selling farm equipment. After a series of physical and mental breakdowns, he ended up in a sanitarium in Battle Creek, Michigan, where John Henry Kellogg held sway. Kellogg was of course that Kellogg, and his emphasis on healthy dietary regimes encouraged C.W. Post to launch his own health food company. His first break-through product was a coffee substitute he called Postum. Next came Grape-Nuts cereal and then Post Toasties.

Though Post became rich and famous, his life wasn’t one of ease. Ongoing physical complaints led him to take his own life in 1914, at the age of 59. But his company went to 27-year-old Marjorie, who’d been carefully taught by her father how to run a business. The Postum Company evolved under her leadership into General Foods, via the acquisition of such popular All-American products as Jell-O, Maxwell House coffee, Log Cabin syrup, and later the Birdseye brand of frozen foods.

Marjorie had exquisitely patrician taste. Married four times, she accompanied third husband Joseph E. Davies to Moscow, where he was the second U.S. Ambassador to the Soviet Union (1937-1938). While there she began collecting religious icons and Tsarist treasures that were available for a song to someone with American dollars in hand. Hillwood now houses her magnificent array of Russian artifacts, including dazzling Fabergé Easter Eggs once owned by the Imperial family, as well a charming dacha (summer cottage) nestled in her lush garden. She was also partial to 18th century French porcelain and other objets d’art, but these co-exist with homey family photos in a house that truly reflects its owner’s personality. (She was known to serve Grape-Nuts for breakfast, and offered Jello-O as a dessert at her youngest daughter’s celebrity wedding. Clearly, she was hardly a food snob.)

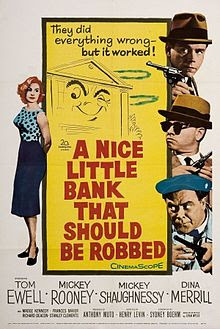

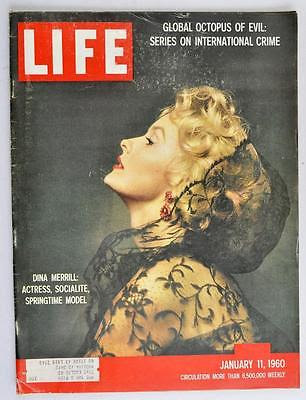

It’s very American to go from rags to riches. And also, when you’ve made your mark, to go Hollywood. Post had three daughters, none of whom seemed better at marriage than she herself was. Second daughter Eleanor’s first of six husbands (1930-1932) was Hollywood film director Preston Sturges. And Marjorie’s third daughter, the only one born from her 1920-1935 marriage to stockbroker E.F. Hutton, herself became minor Hollywood royalty. This was Nedenia Marjorie Hutton, better known Dina Merrill. Beautiful, blonde, and aristocratic, Merrill was once considered America’s next Grace Kelly. (I remember her especially from a trifle called The Courtship of Eddie’s Father in which she plays the socialite who gets rejected by young Eddie—played by little Ronny Howard— as a mate for his widower-dad in favor of the more down-to-earth Shirley Jones.) Merrill, also an active philanthropist, is still alive but suffers from ill health at age 92.

Marjorie Merriweather Post may have been rich, but she never forgot to be generous--nor patriotic. In later years, she regularly gave lawn parties for wounded military veterans. And during World War II she sold her luxury yacht to the U.S. government as a troop ship for the massive price of $1. Though Hillwood was given to the American nation, Marjorie’s Palm Beach, Florida estate has had a different future. She envisioned Mar-a-lago as a retreat for future U.S. presidents. It was bought by Donald Trump in 1985 . . . so anything’s possible.

Published on July 08, 2016 11:09

July 5, 2016

Garrison Keillor: Definitely Above Average

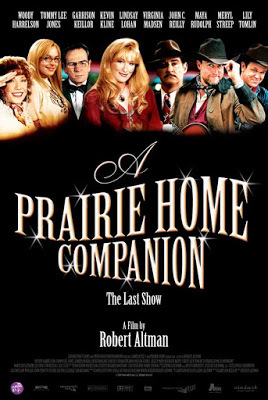

It doesn’t get more All-American than Garrison Keillor, who just wrapped up his final episode as writer, host, duet-partner, and comic monologist for Public Radio’s A Prairie Home Companion. I don’t know what we’ll all do without his news from Lake Wobegon, his earnest ads for such homey fictitious products as Powdermilk Biscuits (“Heavens, they’re tasty – and expeditious!”) and his public service announcements touting the Professional Organization of English Majors and the Ketchup Advisory Board .

Once radio was America’s favorite form of home entertainment. Families would gather around the big radio console in the living room to laugh at Fibber McGee, Fred Allen, and Amos ‘n’ Andy. Then TV sitcoms replaced radio, and the intimate art of telling stories over the air was lost . . . nearly. In 1974, Keillor launched A Prairie Home Companion, an unabashedly folksy hour of shaggy-dog stories, serials featuring elaborate sound effects (“Guy Noir, Private Eye”), folk music, and mock commercials. It was performed in front of live audiences,who participated in singalongs and contributed messages to absent loved ones.

Humorists in America have traditionally sprung from newly arrived immigrant groups and social outcasts. For much of the twentieth century, the most prominent comic performers were Jewish, even those (like Jack Benny) who changed their names to reflect the majority culture. Starting in the Sixties, we saw the rise of the African-American comedian, whose outsider status gave him the perspective to mock mainstream American life. More recently we’ve have gay comics, Middle Eastern comics, and others who make their home on the fringes of our society.

Then there’s Keillor, who at first glance couldn’t be more socially entrenched. He’s a WASP from the heartland: Minnesota, to be exact. Yet he couldn’t be further from the hip urbanism that’s considered cool in today’s performers. He’s tall and a bit ungainly, and the religious tradition from which he hails is strongly evangelical. My friend and colleague Barbara Burkhardt, who is hard at work on a definitive Keillor biography, tells me that his material often reflects his own struggles with his family’s strong religious bent. No wonder he seems to quietly crusade on behalf of “shy persons” and those whose eccentricities make them outcasts within their own communities.

It may seem surprising that Keillor’s very last regular broadcast of A Prairie Home Companion did not take place at the Fitzgerald Theatre, his usual stomping ground in St. Paul. Rather, the broadcast was set on my home turf, at L.A.’s glamorous Hollywood Bowl. That’s why the last show lampoons SoCal’s beautiful people, emphasizing our obsession with physical fitness and our own good looks. I’ve been told that Keillor’s decision to retire at this particular moment (which may reflect some health issues) was made after the show’s touring schedule was already set, and that there will be a hometown farewell at a later date. But I continue to wonder, now that Keillor is retiring from a weekly broadcast, if in fact he has Hollywood in his sights.

Back in 2006 there was a Prairie Home Companion film. Keillor wrote the script and starred as a version of himself for the great Robert Altman who directed this as his final project. The subject of the film is the show’s pending cancellation. And Death lurks in the wings. I certainly hope Keillor’s retirement is less melancholy. Like Lake Wobegon’s children, he’s much too far above average to be forgotten anytime soon.

Published on July 05, 2016 12:08

Beverly in Movieland

I write twice weekly, covering topics relating to movies, moviemaking, and growing up Hollywood-adjacent. I believe that movies can change lives, and I'm always happy to hear from readers who'd like t

I write twice weekly, covering topics relating to movies, moviemaking, and growing up Hollywood-adjacent. I believe that movies can change lives, and I'm always happy to hear from readers who'd like to discuss that point.

...more

- Beverly Gray's profile

- 10 followers